Plovdiv

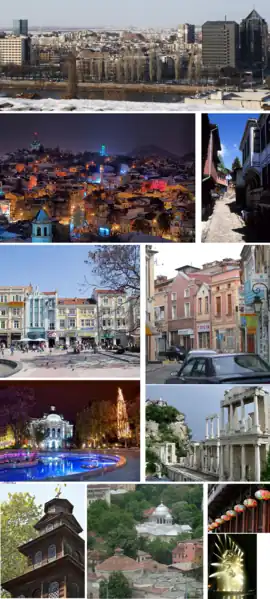

Plovdiv (Bulgarian: Пловдив, pronounced [ˈpɫɔvdif]) is the second-largest city in Bulgaria, standing on the banks of the Maritsa river in the historical region of Thrace, behind the state capital Sofia. It has a population of 346,893 as of 2018 and 675,000 in the greater metropolitan area. Plovdiv is a cultural hub in Bulgaria and was the European Capital of Culture in 2019. The city is an important economic, transport, cultural, and educational center. Plovdiv joined the UNESCO Global Network of Learning Cities in 2016.

Plovdiv

Пловдив | |

|---|---|

From top, left to right:

Hills of Plovdiv • Ancient theatre • Ancient stadium • Historical Museum • Hisar Kapia • Ethnographic Museum • Tsar Simeon's garden • | |

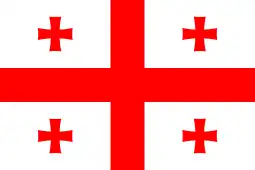

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nickname(s): The city of the seven hills Градът на седемте хълма (Bulgarian) Gradăt na sedemte hălma (transliteration) | |

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates: 42°9′N 24°45′E | |

| Country | Bulgaria |

| Province | Plovdiv |

| Municipalities | Plovdiv-city |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Zdravko Dimitrov (GERB) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 101.98 km2 (39.37 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 164 m (538 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 346,893 |

| • Urban | 544,628[2] |

| • Metro | 675,586[3] |

| Demonym | Plovdivchanin/Plovdivchanka |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal code | 4000 |

| Area code | (+359) 032 |

| Car plates | PB |

| Website | www.plovdiv.bg |

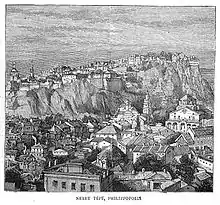

Plovdiv is situated in a fertile region of south-central Bulgaria on the two banks of the Maritsa River. The city has historically developed on seven syenite hills, some of which are 250 metres (820 feet) high. Because of these hills, Plovdiv is often referred to in Bulgaria as "The City of the Seven Hills". There is evidence of habitation in the area dating back to the 6th millennium BCE, when the first Neolithic settlements were established. The city was subsequently a local Thracian settlement, later being conquered and ruled also by Persians, Ancient Macedonians, Celts, Romans, Byzantines, Goths, Huns, Bulgarians (Thracians, Bulgars, Slavic tribes, etc.), Crusaders, and Ottoman Turks.[4]

Philippopolis (Greek: Φιλιππούπολις) was founded as a polis by the father of Alexander the Great, Philip the Great (r. 359–336 BCE), the king of ancient Macedonia, settling there both Thracians and 2,000 Macedonians and Greeks in 342 BCE.[5] Control of the city alternated between the Macedonian kingdom and the Thracian Odrysian kingdom during the Hellenistic period; the Macedonian king Philip V (r. 221–179 BCE) reoccupied the city in 183 BCE and his successor Perseus (r. 179–168 BCE) held the city with the Odrysians until the Roman Republic conquered the Macedonian kingdom in 168 BCE.[5] Philippopolis became the capital of the Roman province of Thracia.[5] The city was at the centre of the road network of inland Thrace, and the strategic Via Militaris was crossed by several other roads at the site, leading to the Danube, the Aegean Sea, and the Black Sea. The Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (r. 161–180 CE) built a new wall around the city.[5]

In Late Antiquity, Philippopolis was an important stronghold, but was sacked in 250 during the Crisis of the Third Century,[5] after the Siege of Philippopolis by the Goths led by Cniva. After this the settlement contracted, though it remained a major city, with the city walls rebuilt and new Christian basilicas and Roman baths constructed in the 4th century.[6][7] The city was again sacked by the Huns in 441/442, and the walls were again rebuilt.[7] Roman Philippopolis resisted another attack, by the Avars in the 580s, after the walls were renewed yet again by Justinian the Great (r. 527–565).[7]

In the Middle Ages, Philippopolis fell to the Bulgars of the First Bulgarian Empire in 863, during the reign of Boris I (r. 852–889), having been briefly abandoned by the Christian inhabitants in 813 during a dispute with the khan Krum (r. c. 803 – 814).[7][6] During the Byzantine–Bulgarian wars, the emperor Basil the Bulgar-Slayer (r. 960–1025) used Philippopolis as a major strategic fortification, governed by the protospatharios Nikephoros Xiphias.[6] In the middle 11th century, the city was attacked by the Pechenegs, who occupied it briefly around 1090.[6] The city continued to prosper, with the walls restored in the 12th century, during which the historian and politician Niketas Choniates was its governor and the physician Michael Italikos was its metropolitan bishop.[6] According to the Latin historian of the Fourth Crusade, Geoffrey of Villehardouin, Philippopolis was the third largest city in the Byzantine Empire, after Constantinople (Istanbul) and Thessalonica (Thessaloniki).[6] It suffered damage from the armies passing through the city during the Crusades as well as from sectarian violence between the Eastern Orthodox and the Armenian Orthodox and Paulician denominations.[6] The city was destroyed by Kaloyan of Bulgaria (r. 1196–1207) in 1206 and rebuilt thereafter.[6] In 1219, the city became the capital of the Crusader Duchy of Philippopolis, part of the Latin Empire.[6] The Second Bulgarian Empire recovered the city in 1263, but lost it to Byzantine control before recapturing it in 1323.[6] The Ottoman Empire conquered Philippopolis (Turkish: Filibe) in 1363 or 1364.[6] During the 500 years of Ottoman rule, Filibe served as one of the important commercial and transportation nodes in the Ottoman Balkans. It also played a role as an administrative centre of various sanjaks and eyalets.

On 4 January 1878, at the end of the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878), Plovdiv was taken away from Ottoman rule by the Russian army. It remained within the borders of Bulgaria until July of the same year, when it became the capital of the autonomous Ottoman region of Eastern Rumelia. In 1885, Plovdiv and Eastern Rumelia joined Bulgaria.

There are many preserved ruins such as the ancient Plovdiv Roman theatre, a Roman odeon, a Roman aqueduct, the Plovdiv Roman Stadium, the archaeological complex Eirene, and others. Plovdiv is host to a huge variety of cultural events such as the International Fair Plovdiv, the international theatrical festival "A stage on a crossroad", the TV festival "The golden chest", and many more novel festivals, such as Night/Plovdiv in September, Kapana Fest, and Opera Open. The oldest American educational institution outside the United States, the American College of Sofia, was founded in Plovdiv in 1860 and later moved to Sofia.

On 5 September 2014, Plovdiv was selected as the Bulgarian host of the European Capital of Culture 2019 alongside the Italian city of Matera.[8] This happened with the help of the Municipal Foundation "Plovdiv 2019″, a non-government organization, which was established in 2011 by Plovdiv's City Council whose main objectives were to develop and to prepare Plovdiv's bid book for European Capital of Culture in 2019.

Etymology

Plovdiv has been given various names throughout its long history. The Odrysian capital Odryssa (Greek: ΟΔΡΥΣΣΑ, Latin: ODRYSSA) is suggested to have been modern Plovdiv by numismatic research[9][10] or Odrin.[11] The Greek historian Theopompus[12] mentioned it in the 4th century BCE as a town named Poneropolis (Greek: ΠΟΝΗΡΟΠΟΛΙΣ "town of villains") in pejorative relation to the conquest by king Philip II of Macedon who is said to have settled the town with 2,000 men who were false-accusers, sycophants, lawyers, and other possible disreputables.[13] According to Plutarch, the town was named by this king after he had populated it with a crew of rogues and vagabonds,[14] but this is possibly a folk name that did not actually exist.[11] The names Dulon polis (Greek: ΔΟΥΛΩΝ ΠΟΛΙΣ "slaves' town") and possibly Moichopolis (Greek: ΜΟΙΧΟΠΟΛΙΣ "adulterer's town") likely have similar origins.

The city has been called Philippopolis (ΦΙΛΙΠΠΟΠΟΛΙΣ pronounced [pʰilipopolis]; Greek: Φιλιππούπολη, in modern Greek, Philippoupoli pronounced [filipupoli]) or "the city of Philip", from Greek Philippos "horse-lover", most likely in honor of Philip II of Macedon[15] after his death or in honor of Philip V,[9][16] as this name was first mentioned in the 2nd century BCE by Polybius in connection with the campaign of Philip V.[9][16] Philippopolis was identified later by Plutarch and Pliny as the former Poneropolis. Strabo identified Philip II's settlement of most "evil, wicked" (Gr. πονηροτάτους ponerotatous) as Calybe (Kabyle),[17] whereas Ptolemy considered the location of Poneropolis different from the rest.

Kendrisia (Greek: ΚΕΝΔΡΕΙϹΕΙΑ) was an old name of the city.[4] Its earliest recorded use is on an artifact mentioning that king Beithys, priest of the Syrian goddess, brought gifts to Kendriso Apollo;[18] the deity is recorded to be named multiple times after different cities. Later Roman coins mentioned the name which is possibly derived from Thracian god Kendriso who is equated with Apollo,[19] the cedar forests, or from the Thracian tribe artifacts known as the kendrisi.[4][16] Another assumed name is the 1st century CE Tiberias in honor of the Roman emperor Tiberius, under whom the Odrysian Kingdom was a client of Rome.[11] After the Romans had taken control of the area, the city was named in Latin: TRIMONTIUM, meaning "The Three Hills", and mentioned in the 1st century by Pliny. At times the name was Ulpia, Flavia, Julia after the Roman families.

Ammianus Marcellinus wrote in the 4th century CE that the then city had been the old Eumolpias/Eumolpiada, (Latin: EVMOLPIAS, EVMOLPIADA),[20] the oldest name chronologically.[11] It was named after the mythical Thracian king Eumolpos, son of Poseidon[21] or Jupiter,[22] who may have founded the city around 1200 BCE[23] or 1350 BCE.[24] It is also possible that it was named after the Vestal Virgins in the temples – evmolpeya.[4]

In the 6th century CE, Jordanes wrote that the former name of the city was Pulpudeva (Latin: PVLPVDEVA) and that Philip the Arab named the city after himself. This name is most likely a Thracian oral translation[4] of the other as it kept all consonants of the name Philip + deva (city). Although the two names sound similar, they may not share the same origin as Odrin and Adrianople do, and Pulpudeva may have predated the other names[25][26] meaning "lake city" in Thracian.[16] Since the 9th century CE the Slavic name began to appear as Papaldiv/n, Plo(v)div, Pladiv, Pladin, Plapdiv, Plovdin, which originate from Pulpudeva.[27] As a result, the name has lost any meaning. In British English the Bulgarian variant Plòvdiv has become prevalent after World War I. The Crusaders mentioned the city as Prineople, Sinople and Phinepople.[16] The Ottomans called the city Filibe, a corruption of "Philip", in a document from 1448.[28]

Geography

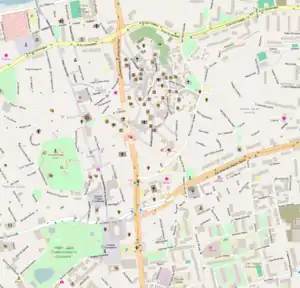

Plovdiv is located on the banks of the Maritsa river, southeast of the Bulgarian capital Sofia. The city is in the southern part of the Plain of Plovdiv, an alluvial plain that forms the western portion of the Upper Thracian Plain. From there, the peaks of the Sredna Gora mountain range rise to the northwest, the Chirpan Heights to the east, and the Rhodope mountains to the south.[29] Originally, Plovdiv's development occurred south of Maritsa, with expansion across the river taking place only within the last 100 years. Modern Plovdiv covers an area of 101 km2 (39 sq mi), less than 0.1% of Bulgaria's total area. It is the most densely populated city in Bulgaria, with 3,769 inhabitants per km2.

Inside the city proper are six syenite hills. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were seven syenite hills, but one (Markovo tepe) was destroyed. Three of them are called the Three Hills (Bulgarian: Трихълмие Trihalmie), the others are called the Hill of the Youth (Bulgarian: Младежки хълм, Mladezhki halm), the Hill of the Liberators (Bulgarian: Хълм на освободителите, Halm na osvoboditelite), and the Hill of Danov (Bulgarian: Данов хълм, Danov halm).[30]

Climate

Plovdiv has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) with considerable humid continental influences. There are four distinct seasons with large temperature jumps between seasons.

Summer (mid-May to late September) is hot, moderately dry and sunny, with July and August having an average high of 33 °C (91 °F). Plovdiv sometimes experiences very hot days which are typical in the interior of the country. Summer nights are mild.

Autumn starts in late September; days are long and relatively warm in early autumn. The nights become chilly by September. The first frost usually occurs by November.

Winter is normally cold and snow is common. The average number of days with snow coverage in Plovdiv is 15. The average depth of snow coverage is 2 to 4 cm (1 to 2 in), and the maximum is normally 6 to 13 cm (2 to 5 in), but some winters coverage can reach 70 cm (28 in) or more. The average January temperature is −0.4 °C (31 °F).

Spring begins in March and is cooler than autumn. The frost season ends in March. The days are mild and relatively warm in mid-spring.

The average relative humidity is 73% and is highest in December at 86% and the lowest in August at 62%. The total precipitation is 540 mm (21.26 in) and is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year. The wettest months of the year are May and June, with an average precipitation of 66.2 mm (2.61 in), and the driest month is August, with an average precipitation of 31 mm (1.22 in).

Gentle winds (0 to 5 m/s) are predominant in the city with wind speeds of up to 1 m/s, representing 95% of all winds during the year. Mists are common in the cooler months, especially along the banks of the Maritsa. On average there are 33 days with mist during the year.[31]

| Climate data for Plovdiv (1952–2000; extremes 1942–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 23.0 (73.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

30.0 (86.0) |

34.2 (93.6) |

36.0 (96.8) |

41.0 (105.8) |

45.0 (113.0) |

42.5 (108.5) |

37.6 (99.7) |

36.8 (98.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

22.9 (73.2) |

45.0 (113.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

18.4 (65.1) |

23.7 (74.7) |

28.0 (82.4) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.3 (86.5) |

26.0 (78.8) |

19.4 (66.9) |

11.9 (53.4) |

6.4 (43.5) |

18.5 (65.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 0.9 (33.6) |

3.2 (37.8) |

7.2 (45.0) |

12.3 (54.1) |

17.3 (63.1) |

21.5 (70.7) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.2 (73.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

13.1 (55.6) |

6.9 (44.4) |

2.3 (36.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.0 (26.6) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

1.8 (35.2) |

6.2 (43.2) |

11.0 (51.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

17.0 (62.6) |

16.5 (61.7) |

12.6 (54.7) |

7.6 (45.7) |

2.6 (36.7) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −31.5 (−24.7) |

−29.1 (−20.4) |

−17.5 (0.5) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

5.6 (42.1) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−22.7 (−8.9) |

−31.5 (−24.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 27 (1.1) |

34 (1.3) |

37 (1.5) |

41 (1.6) |

77 (3.0) |

57 (2.2) |

39 (1.5) |

43 (1.7) |

35 (1.4) |

37 (1.5) |

36 (1.4) |

39 (1.5) |

502 (19.8) |

| Average precipitation days | 4.8 | 5.1 | 5.8 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 6.2 | 3.8 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 5.8 | 6.2 | 60.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 67 | 60 | 53 | 53 | 50 | 45 | 46 | 48 | 59 | 69 | 76 | 59 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 94 | 110 | 170 | 200 | 252 | 281 | 328 | 315 | 230 | 162 | 120 | 77 | 2,339 |

| Source 1: Climatebase.ru | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Danish Meteorological Institute (sun and relative humidity),[32] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Plovidiv (2008-2021) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.3 (45.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.3 (66.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

28.7 (83.7) |

32.1 (89.8) |

31.8 (89.2) |

26.9 (80.4) |

21.5 (70.7) |

15.3 (59.5) |

8.8 (47.8) |

21 (70) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.2 (36.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

8.5 (47.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

25.5 (77.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

10.7 (51.3) |

4.6 (40.3) |

14.0 (57.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.0 (30.2) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

3.6 (38.5) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.3 (63.1) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.8 (65.8) |

15.1 (59.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.3 (43.3) |

0.5 (32.9) |

9.3 (48.8) |

| Source: Stringmeteo.com | |||||||||||||

History

| History of Plovdiv | |

|---|---|

| Timeline of events | |

| 6000–5000 BC | Establishment of the earliest settlements on the territory of modern Plovdiv (Yasa Tepe 1 and Yasa Tepe 2) |

| 5th century BC | Ancient Plovdiv was incorporated into the Odrysian kingdom |

| 347–342 BC | The Thracian town was conquered by Philip II of Macedon who named it Philippopolis |

| 46 | Philippopolis was incorporated into the Roman Empire by emperor Claudius |

| 1st–3rd century | Philippopolis became the central city of the Roman province Thracia |

| 250 | The whole city was burned down by the Goths |

| 4th century | Philippopolis regained its previous size. The city was part of the Eastern Roman Empire |

| 836 | Khan Malamir incorporated the city into the First Bulgarian Empire |

| 976–1014 | Basil II based his army in Philippopolis during the war with Samuel of Bulgaria |

| 1189 | The city was conquered by the crusader army of Frederick Barbarossa |

| 1205 | Philippopolis was conquered and raided by the Latin Empire and Kaloyan of Bulgaria |

| 1371 | Phillipopolis was conquered by the Ottomans. The city name was changed to Filibe |

| January 1878 | Plovdiv was liberated from Ottoman rule during the Battle of Philippopolis |

| July 1878 | Plovdiv became capital of Eastern Rumelia |

| 1885 | Plovdiv is at the center of the events that led to the Bulgarian unification |

| 1920–1960 | Period of industrialization |

| 1970-1980 | Discovery of the archeological sights in Plovdiv, the Old town was restored |

| 1999 | Plovdiv hosted European Cultural Month |

| 2014 | Plovdiv was awarded the title European capital of culture 2019 |

Antiquity

.JPG.webp)

| Part of a series on the ancient city of |

| Philippopolis |

|---|

|

| Buildings and structures |

|

Religious Fortification Residential |

| Related topics |

The history of the region spans more than eight millennia. Numerous nations have left their traces on the twelve-metre-thick (39-foot) cultural layers of the city. The earliest signs of habitation in the territory of Plovdiv date as far back as the 6th millennium BCE.[33][4] Plovdiv has settlement traces including necropolises dating from the Neolithic era (roughly 6000–5000 BCE) like the mounds Yasa Tepe 1 in the Philipovo district and Yasa Tepe 2 in Lauta park.[34][35][36] Archaeologists have discovered fine pottery and objects of everyday life on Nebet Tepe from as early as the Chalcolithic era, showing that at the end of the 4th millennium BCE, there was already an established settlement there which was continuously inhabited since then.[37][38][39] Thracian necropolises dating back to the 2nd–3rd millennium BCE have been discovered, while the Thracian town was established between the 2nd and the 1st millennium BCE.

The town was a fort of the independent local Thracian tribe Bessi.[40] In 516 BCE during the rule of Darius the Great, Thrace was included in the Persian empire.[41] In 492 BCE, the Persian general Mardonius subjugated Thrace again, and it nominally became a vassal of Persia until 479 BCE and the early rule of Xerxes I.[42] The town became part of the Odrysian kingdom (460 BCE – 46 CE), a Thracian tribal union. The town was conquered by Philip II of Macedon,[43] and the Odrysian king was deposed in 342 BCE. Ten years after the Macedonian invasion, the Thracian kings started to exercise power again after the Odrysian Seuthes III had re-established their kingdom under Macedonian suzerainty as a result of a successful revolt against Alexander the Great's rule resulting in a stalemate.[44] The Odrysian kingdom gradually overcame the Macedonian suzerainty, while the city was destroyed by the Celts as part of the Celtic settlement of Eastern Europe, most likely in the 270s BCE.[45] In 183 BCE, Philip V of Macedon conquered the city, but shortly after, the Thracians re-conquered it.

In 72 BCE, the city was seized by the Roman general Marcus Lucullus but was soon restored to Thracian control. In 46 CE, the city was finally incorporated into the Roman Empire by emperor Claudius;[46] it served as the capital of the province of Thrace. Although it was not the capital of the Province of Thrace, the city was the largest and most important centre in the province.[47] As such, the city was the seat of the Union of Thracians.[48] In those times, the Via Militaris (or Via Diagonalis), the most important military road in the Balkans, passed through the city.[49][50] The Roman times were a period of growth and cultural excellence.[51] The ancient ruins tell a story of a vibrant, growing city with numerous public buildings, shrines, baths, theatres, a stadium, and the only developed ancient water supply system in Bulgaria. The city had an advanced water system and sewerage. In 179 a second wall was built to encompass Trimontium which had already extended out of the Three hills into the valley. Many of those are still preserved and can be seen by tourists. Today only a small part of the ancient city has been excavated.[52]

In 250 the city was captured and looted after the Battle of Philippopolis by the Goths, led by their ruler Cniva. Many of its citizens, 100,000 according to Ammianus Marcellinus, died or were taken captive.[53] It took a century and hard work to recover the city. However, it was destroyed again by Attila's Huns in 441–442 and by the Goths of Teodoric Strabo in 471.[54]

An ancient Roman inscription written in Ancient Greek dated to 253 – 255 AD were discovered in the Great Basilica. The inscription refers to the Dionysian Mysteries and also mentions Roman Emperors Valerian and Gallienus. It has been found on a large stele which was used as construction material during the building of the Great Basilica.[55]

Middle Ages

The Slavs had fully settled in the area by the middle of the 6th century. This was done peacefully as there are no records for their attacks.[56] With the establishment of Bulgaria in 681, Philippoupolis, the name of the city then, became an important border fortress of the Byzantine Empire. It was captured by Khan Krum in 812, but the region was fully incorporated into the Bulgarian Empire in 834 during the reign of Khan Malamir.[57] It was reconquered by the Byzantine Empire in 855–856 for a short time until it was returned to Boris I of Bulgaria.[58][59] From Philippopolis, the influence of dualistic doctrines spread to Bulgaria forming the basis of the Bogomil heresy. The city remained in Bulgarian hands until 970.[60] However, the city is described at the time of Constantine VII in the 10th century as being within the Byzantine province (theme of Macedonia). Philippopolis was captured by the Byzantines in 969, shortly before it was sacked by the ruler of Rus' Sviatoslav I of Kiev who impaled 20,000 citizens.[61] Before and after the Rus' massacre, the city was settled by Paulician heretics transported from Syria and Armenia to serve as military settlers on the European frontier with Bulgaria. Aime de Varennes in 1180 encountered the singing of Byzantine songs in the city that recounted the deeds of Alexander the Great and his predecessors over 1300 years before.[62]

Byzantine rule was interrupted by the Third Crusade (1189–1192) when the army of the Holy Roman emperor Frederick Barbarossa conquered Philippopolis. Ivanko was appointed as the governor of the Byzantine Theme of Philippopolis in 1196, but between 1198 and 1200 separated it from Byzantium in a union with Bulgaria. The Latin Empire conquered Philippopolis in 1204, and there were two short interregnum periods as the city was twice occupied by Kaloyan of Bulgaria before his death in 1207.[63] In 1208, Kaloyan's successor Boril was defeated by the Latins in the Battle of Philippopolis.[64] Under Latin rule, Philippopolis was the capital of the Duchy of Philippopolis, which was governed by Renier de Trit and later on by Gerard de Strem. The city was possibly at times a vassal of Bulgaria or Venice. Ivan Asen II conquered the duchy finally in 1230 but the city had possibly been conquered earlier.[65] Afterwards, Philippopolis was conquered by Byzantium. According to some information, by 1300 Philippopolis was a possession of Theodore Svetoslav of Bulgaria. It was conquered from Byzantium by George Terter II of Bulgaria in 1322.[66] Andronikos III Palaiologos unsuccessfully besieged the city, but a treaty restored Byzantine rule once again in 1323. In 1344 the city and eight other cities were surrendered to Bulgaria by the regency for John V Palaiologos as the price for Ivan Alexander of Bulgaria's support in the Byzantine civil war of 1341–47.[67]

Ottoman rule

In 1364 the Ottoman Turks under Lala Shahin Pasha seized Plovdiv.[68][69] According to other data, Plovdiv was not an Ottoman possession until the Battle of Maritsa in 1371, after which, the citizens and the Bulgarian army fled leaving the city without resistance. Refugees settled in Stanimaka. During the Ottoman Interregnum in 1410, Musa Çelebi conquered the city killing and displacing inhabitants.[70] The city was the centre of the Rumelia Eyalet from 1364 until 1443, when it was replaced by Sofia as the capital of Rumelia. Plovdiv served as a sanjak centre within Rumelia between 1443 and 1593, the sanjak centre in Silistra Eyalet between 1593 and 1826, the sanjak centre in Eyalet of Adrianople between 1826 and 1867, and the sanjak centre of Edirne Vilayet between 1867 and 1878. During that period, Plovdiv was one of the major economic centers in the Balkans, along with Istanbul (Constantinople), Edirne, Thessaloniki, and Sofia. The richer citizens constructed beautiful houses, many of which can still be seen in the architectural reserve of Old Plovdiv. From the early 15th century till the end of 17th century the city was predominantly inhabited by Muslims.[71]

National revival

Under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, Filibe (as the city was known at that time) was a focal point for the Bulgarian national movement and survived as one of the major cultural centers for Bulgarian culture and tradition.

Filibe was described as consisting of Turks, Bulgarians, Hellenized Bulgarians, Armenians, Jews, Vlachs, Arvanites, Greeks, and Roma people. In the 16–17 century a significant number of Sephardic Jews settled along with a smaller Armenian community from Galicia. The Paulicians adopted Catholicism or lost their identity. The abolition of Slavonic as the language of the Bulgarian Church as well as the complete abolition of the church in 1767 and the introduction of the Millet System led to ethnic division among people of different religions. Christian and Muslim Bulgarians were subjected to Hellenization and Turkification respectively. A major part of the inhabitants was fully or partly Hellenized due to the Greek patriarchate. The "Langeris" are described as Greeks from the area of the nearby Stenimachos. The process of Hellenization flourished until the 1830s but declined with the Tanzimat as the idea of the Hellenic nation of Christians grew and was associated with ethnic Greeks.

The re-establishment of the Bulgarian Church in 1870 was a sign of ethnic and national consciousness. Thus, although there is a little doubt about the Bulgarian origin of the Gulidas, the city could be considered of Greek or Bulgarian majority in the 19th century.[72] Raymond Detrez has suggested that when the Gudilas and Langeris claimed to be Greek it was more in the sense of "Romei than Ellines, in a cultural rather than an ethnic sense".[73] According to the statistics by the Bulgarian and Greek authors, there were no Turks in the city; according to an alternative estimate the city was of Turkish majority.[74]

Filibe had an important role in the struggle for Church independence which was, according to some historians, a peaceful bourgeois revolution. Filibe became the center of that struggle with leaders such as Nayden Gerov, Dr Valkovich, Joakim Gruev, and whole families. In 1836 the first Bulgarian school was inaugurated, and in 1850, modern secular education began when the "St Cyrill and Methodius" school was opened. On 11 May 1858, the day of Saints Cyril and Methodius was celebrated for the first time; this later became a National holiday which is still celebrated today (but on 24 May due to Bulgaria's 1916 transition from the Old Style (Julian) to the New Style (Gregorian) calendar). In 1858 in the Church of Virgin Mary, the Christmas liturgy was served for the first time in the Bulgarian language since the beginning of the Ottoman occupation. Until 1906 there were Bulgarian and Greek bishops in the city. In 1868 the school expanded into the first grammar school. Some of the intellectuals, politicians, and spiritual leaders of the nation graduated that school.[16]

The city was conquered by the Russians under Aleksandr Burago for several hours during the Battle of Philippopolis on 17 January 1878.[69] It was the capital of the Provisional Russian Administration in Bulgaria between May and October. According to the Russian census of the same year, Filibe had a population of 24,000 citizens, of which ethnic Bulgarians comprised 45.4%, Turks 23.1% and Greeks 19.9%.

Eastern Rumelia

According to the Treaty of San Stefano on 3 March 1878, the Principality of Bulgaria included the lands with predominantly Bulgarian population. Plovdiv which was the biggest and most vibrant Bulgarian city was selected as a capital of the restored country and for a seat of the Temporary Russian Government.[75] Great Britain and Austria-Hungary, however, did not approve that treaty and the final result of the war was concluded in the Congress of Berlin which divided the newly liberated country into several parts. It separated the autonomous region of Eastern Rumelia from Bulgaria, and Plovdiv became its capital. The Ottoman Empire created a constitution and appointed a governor.[76]

In the spring of 1885, Zahari Stoyanov formed the Secret Bulgarian Central Revolutionary Committee in the city which actively conducted propaganda for the unification of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia. On 5 September, several hundred armed rebels from Golyamo Konare (now Saedinenie) marched to Plovdiv. In the night of 5–6 September, these men, led by Danail Nikolaev, took control of the city and removed from office the General-Governor Gavril Krastevich. A provisional government was formed led by Georgi Stranski, and universal mobilization was announced.[77] After the Serbs were defeated in the Serbo-Bulgarian War, Bulgaria and Turkey reached an agreement that the Principality of Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia had a common government, Parliament, administration, and army. Today, 6 September is celebrated as the Unification Day and the Day of Plovdiv.

Recent history

After the unification, Plovdiv remained the second most populous city in Bulgaria after the capital Sofia. The first railway in the city was built in 1874 connecting it with the Ottoman capital, and in 1888, it was linked with Sofia. In 1892 Plovdiv became the host of the First Bulgarian Fair with international participation which was succeeded by the International Fair Plovdiv. After the liberation, the first brewery was inaugurated in the city.

The noteworthy English travel writer Patrick Leigh Fermor visited Plovdiv in the late summer of 1934 and he was charmed by the town and a local woman name Nadjeda.[78]

In the beginning of the 20th century, Plovdiv grew as a significant industrial and commercial center with well-developed light and food industry. In 1927 the electrification of Plovdiv has started. German, French, and Belgian capital was invested in the city in the development of modern trade, banking, and industry. In 1939, there were 16,000 craftsmen and 17,000 workers in manufacturing factories, mainly for food and tobacco processing. During the Second World War, the tobacco industry expanded as well as the export of fruit and vegetables. In 1943, 1,500 Jews were saved from deportation in concentration camps by the archbishop of Plovdiv, Cyril, who later became the Bulgarian Patriarch. In 1944, the city was bombed by the British-American coalition.

Tobacco Depot workers went on strike on 4 May 1953.

On 6 April 1956 the first trolleybus line was opened and in the 1950s the Trimontsium Hotel was constructed. In the 1960s and 1970s, there was a construction boom and many of the modern neighborhoods took shape. In the 1970s and 1980s, antique remains were excavated and the Old Town was fully restored. In 1990 the sports complex "Plovdiv" was finished. It included the largest stadium and rowing canal in the country. In that period, Plovdiv became the birthplace of Bulgaria's movement for democratic reform, which by 1989 had garnered enough support to enter government.

Plovdiv has hosted specialized exhibitions of the World's Fair in 1981, 1985, and 1991.

Population

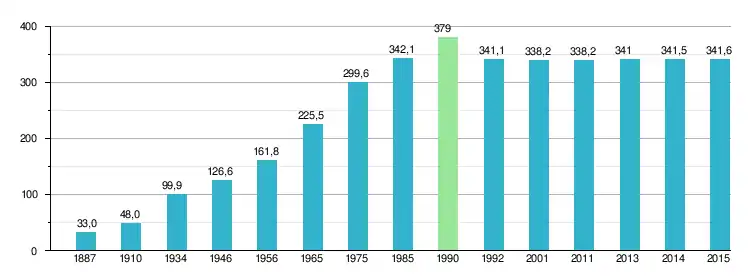

The population by permanent address for the municipality of Plovdiv for 2007 is 380,682,[79] which makes it the second in population in the nation. According to data from the National Institute of Statistics (NSI), the population of people who actually live in Plovdiv is 346,790.[80] According to the 2012 census, 339,077 live within the city limits and 403,153 in the municipal triangle of Plovdiv, including Maritsa municipality and Rodopi municipality.[81] Population of Plovdiv:

| Plovdiv | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1887 | 1910 | 1934 | 1946 | 1956 | 1965 | 1975 | 1985 | 1992 | 2001 | 2005 | 2009 | 2011 | 2021 | |

| Population | 33,032 | 47,981 | 99,883 | 126,563 | 161,836 | 225,508 | 299,638 | 342,131 | 341,058 | 338,224 | 341,9 | 338,2 | 338,153 | 343,070 | |

| Highest number 348,465 in 2009 | |||||||||||||||

| Sources: National Statistical Institute,[82][83][84] citypopulation.de,[85] pop-stat.mashke.org,[86] Bulgarian Academy of Sciences[87] | |||||||||||||||

At the first census after the Liberation of Bulgaria in 1880 with 24,053 citizens,[88] Plovdiv was the third largest city behind Stara Zagora, which had 25,460 citizens prior to being burnt to the ground[89] as well as Ruse, which had 26,163 citizens then,[90] and ahead of the capital Sofia, which had 20,501 citizens then. As of the 1887 census, Plovdiv was the largest city in the country for several years with 33,032 inhabitants compared to 30,428 for Sofia. According to the 1946 census, Plovdiv was the second largest city with 126,563 inhabitants compared to 487,000 for the capital.[75]

Ethnicity and religion

| Year[91] | Muslims | Christians | Roma | Jews |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1472 | 81.7% | 18.3% | ||

| 1489 | 87.1% | 8.2% | 3.5% | |

| 1490 (households)[92] | 796 | 78 | 33 | |

| 1516 | 86.7% | 7% | 2.8% | 2.5% |

| 1525 | 85.2% | 7.5% | 3.2% | 3% |

| 1530 | 82.1% | 9.1% | 3.8% | 3.7% |

| 1570 | 82% | 9.3% | 2.7% | 5.4% |

| 1595 | 78.2% | 14% | 2.9% | 4.8% |

| 1614 | 68.3% | 22.6% | 7.7% | 4.1% |

| 1695[70] | 81% | 14% | ||

| 1876[93] | 33% |

| Census | Total | Bulgarians | Turks | Jews | Greeks | Armenians | Roma | Others | Unspecified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1878 | 24053[94] | 10909 (45.35%) | 5558 (23.10%) | 1134 (4.71%) | 4781 (19.88%) | 806 (3.35%) | 865 (3.60%) | 902 (3.75%) | |

| 1884[95]

– |

33442 | 16752 (50.09%) | 7144 (21.36%) | 2168 (6.48%) | 5497 (16.44%) | 979 (2.93%) | 112 | 902 (2.70%) | |

| 1887 | 33032 | 19542 | 5615 | 2202 | 3930 | 903 | 348 | 492 | |

| 1892 | 36033 | 20854 | 6381 | 2696 | 3906 | 1024 | 237 | 935 | |

| 1900 | 43033 | 24170 | 4708 | 3602 | 3908 | 1844 | 1934 | 2869 | |

| 1910 | 47981 | 32727 | 2946 | 4436 | 1571 | 1794 | 3524 | 983 | |

| 1920 | 64415 | 46889 | 5605 | 5144 | 1071 | 3773 | 1342 | 591 | |

| 1926 | 84655 | 63268 | 4748 | 5612 | 549 | 5881 | 2746 | 1851 | |

| 1934 | 99883 | 77449 | 6102 | 5574 | 340 | 5316 | 2728 | 2374 | |

| 1939 | 105643 (100%) | 82012 (77.63%) | 6462 (6.12%) | 5960 (5,64%) | 200 (0.19%) | 6591 (6.24%) | 2982 (2.82%) | 1436 (1.36%) | |

| 2001[96] | 338224 | 302858 (89.5%) | 22501 (6.7%) | 5192 (1.5%) | 5764 (1.7%) | 1909 | |||

| 2011[97][98] | 338153 | 277804 (82.2%) | 16032 (4.7%) | 1436 (0.4%) | 9438 (2.8%) | 3105 (0.9%) | 31774 (9.4%) |

In its ethnic character Plovdiv is the second or the third-largest cosmopolitan city inhabited by Bulgarians, after Sofia and possibly Varna. According to the 2001 census, out of a population of 338,224 inhabitants, the Bulgarians numbered 302,858 (90%). Stolipinovo in Plovdiv is the largest Roma neighbourhood in the Balkans, having a population of around 20,000 alone; further Roma ghettos are Hadji Hassan Mahala and Sheker Mahala. Therefore, the census number is a deflation of the number of Roma people, and they are most likely the second-largest group after the Bulgarians, most of all because the Muslim Roma in Plovdiv claim to be of Turkish ethnicity and Turkish-speaking at the census ("Xoraxane Roma").[99] For further information see the article Roma people in Plovdiv. Like elsewhere in the country, Roma people are subjected to discrimination and segregation (See the Bulgaria section of the article Antiziganism).

After the Wars for National Union (Balkan Wars and World War I), the city became home for thousands of refugees from the former Bulgarian lands in Macedonia, Western and Eastern Thrace. Many of the old neighbourhoods are still referred to as Belomorski, Vardarski. Most of the Jews left the city after the foundation of Israel in 1948, as well as most of the Turks and Greeks. Prior to the population exchange, as of 1 January 1885, the city of Plovdiv had a population of 33,442, of which 16,752 were Bulgarians (50%), 7,144 Turks (21%), 5,497 Greeks (16%), 2,168 Jews (6%), 1,061 Armenians (3%), 151 Italians, 112 Germans, 112 Romani people, 80 French people, 61 Russians and 304 people of other nationalities.[95]

The vast majority of the inhabitants are Christians, mostly Eastern Orthodox, Catholics, Eastern Catholics, and Protestant trends (Adventists, Baptists and others). There are also some Muslims and Jews. In Plovdiv, there are many churches, two mosques and one synagogue (see Plovdiv Synagogue).

Some Aromanians also inhabit Plovdiv.[100]

The Virgin Mary Eastern Orthodox Church

The Virgin Mary Eastern Orthodox Church

.JPG.webp) A Protestant church

A Protestant church

St George Armenian Church

St George Armenian Church The Dzhumaya Mosque

The Dzhumaya Mosque The Orthodox seminary

The Orthodox seminary

City government

Plovdiv is the administrative center of Plovdiv Province which consists of the Municipality of Plovdiv, the Maritsa municipality, and the Rodopi municipality. The mayor of the Municipality of Plovdiv, Ivan Totev,[101] with the six district mayors represent the local executive authorities. The Municipal Council which consists of 51 municipal counsellors, represents the legislative power, and is elected according to the proportional system by parties' lists.[102] The executive government of the Municipality of Plovdiv consists of a mayor who is elected by majority representation, five deputy mayors, and one administrative secretary. All the deputy mayors and the secretary control their administrative structured units.

According to the Law for the territorial subdivision of the Capital municipality and the large cities,[103] the territory of Plovdiv Municipality is subdivided into six district administrations with their mayors being appointed following approval by the Municipal Council.

Districts and neighbourhoods

| Number | Neighbourhood | Number | Neighbourhood | Number | Neighbourhood | Number | Neighbourhood |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Center | 12 | Sadiiski | 23 | Hristo Smirnenski | 34 | Sheker Mahala |

| 2 | Old Town | 13 | Stochna Gara | 24 | Proslav | ||

| 3 | Kamenitsa 1 | 14 | Kyutchuk Paris | 25 | Mladezhki Halm | ||

| 4 | Kamenitsa 2 | 15 | Vastannicheski | 26 | Otdih i Kultura | ||

| 5 | Izgrev | 16 | Belomorski | 27 | Marasha | ||

| 6 | Stolipinovo | 17 | Institut po Ovoshtarstvo | 28 | Maritsa Sever | ||

| 7 | Izgrev | 18 | Ostromila | 29 | Zaharna Fabrika | ||

| 8 | Industrial zone – East | 19 | Yuzhen | 30 | Karshiaka | ||

| 9 | Trakia | 20 | Tsentralna Gara | 31 | Gagarin | ||

| 10 | Industrial zone – Trakia | 21 | Komatevo | 32 | Industrial Zone – North | ||

| 11 | Industrial zone – South | 22 | Komatevski Vazel | 33 | Filipovo | ||

In 1969 the villages of Proslav and Komatevo were incorporated into the city. In 1987 the municipalities of Maritsa and Rodopi were separated from Plovdiv which remained their administrative center. In the last several years, the inhabitants from those villages had taken steps to rejoin the "urban" municipality.[104]

Main sights

The city has more than 200 archaeological sites,[105] 30 of which are of national importance. There are many remains from antiquity. Plovdiv is among the few cities with two ancient theatres; remains of the medieval walls and towers; Ottoman baths and mosques; a well-preserved old quarter from the National Revival period with beautiful houses; churches; and narrow paved streets. There are numerous museums, art, galleries and cultural institutions. Plovdiv is host to musical, theatrical, and film events. The Knyaz Alexander I Street is the main street in Plovdiv.

The city is a starting point for trips to places in the region, such as the Bachkovo Monastery at 30 km (19 mi) to the south, the ski-resort Pamporovo at 90 km (56 mi) to the south or the spa resorts to the north Hisarya, Banya, Krasnovo, and Strelcha.[106]

Roman City

The Ancient theatre (Antichen teatur) is probably the best-known monument from antiquity in Bulgaria.[107] During recent archaeological survey, an inscription was found on a postament of a statue at the theatre. It revealed that the site was constructed at the 90s of the 1st century CE. The inscription itself refers to Titus Flavius Cotis, the ruler of the ancient city during the reign of Emperor Domitian.

The Ancient theatre is situated in the natural saddle between two of the Three Hills. It is divided into two parts with 14 rows each divided with a horizontal lane. The theatre could accommodate up to 7,000 people.[108] The three-story scene is on the southern part and is decorated with friezes, cornices, and statues. The theatre was studied, conserved, and restored between 1968 and 1984. Many events are still held on the scene[109] including the Opera Festival Opera Open, the Rock Festival Sounds of the Ages, and the International Folklore festival. The Roman Odeon was restored in 2004.[110] It was built in the 2nd–5th centuries and is the second (and smaller) antique theatre of Philipopolis with 350 seats. It was initially built as a bulevterion, an edifice of the city council, and was later reconstructed as a theatre.

The Ancient Stadium[111] is another important monument of the ancient city. It was built in the 2nd century during the reign of the Roman Emperor Hadrian. It is situated between Danov Hill and one of the Three Hills, beneath the main street from Dzhumaya Square to Kamenitsa Square. It was modelled after the stadium in Delphi. It was approximately 240 metres (790 feet) long and 50 metres (160 feet) wide, and could seat up to 30,000 spectators. The athletic games at the stadium were organised by the General Assembly of the province of Thrace. In their honour, the royal mint of Philippopolis coined money featuring the face of the ruling emperor as well as the types of athletic events held in the stadium. Only a small part of the northern section with 14 seat rows can be seen today; the larger part lies under the main street and a number of buildings.

The Roman forum dates from the reign of Vespasian in the 1st century and was finished in the 2nd century. It is near the modern post office next to the Odeon. It has an area of 11 hectares and was surrounded by shops and public buildings. The forum was a focal point of the streets of the ancient city.[112]

The Eirene Residence is in the southern part of the Three Hills on the northern part of an ancient street in the Archeological underpass. It includes remains of a public building from the 3rd–4th centuries which belonged to a noble citizen. Eirene is the Christian name for Penelopa, a maiden from Megadon, who was converted to Christianity in the 2nd century. There are colourful mosaics which have geometrical forms and figures.[113]

On Nebet hill are the remains of the first settlement which in 12th century BCE grew to the Thracian city of Eumolpias, one of the first cities in Southeastern Europe. Massive walls surrounding a temple and a palace have been excavated. The oldest part of the fortress was constructed from large syenite blocks, the so-called "cyclopean construction".

- Ancient monuments

.jpg.webp)

Roman stadium

Roman stadium

The Bishop's basilica of Phiippopolis

The Bishop's basilica of Phiippopolis

Small bacilica

Small bacilica 3rd century round tower

3rd century round tower Mosaics in Eirene residence

Mosaics in Eirene residence Aqueduct

Aqueduct Nebet tepe

Nebet tepe

Museums and protected sites

The Archaeological Museum was established in 1882 as the People's Museum of Eastern Rumelia.[114] In 1928 the museum was moved to a 19th-century edifice on Saedinenie Square built by Plovdiv architect Josef Schnitter. The museum contains a rich collection of Thracian art. The three sections "Prehistory",[115] "Antiquity",[116] and "Middle Ages"[117] contain precious artifacts from the Paleolithic to the early Ottoman period (15th–16th centuries).[118] The famous Panagyurishte treasure is part of the museum's collection.[119]

The Plovdiv Regional Historical Museum[120] was founded in 1951 as a scientific and cultural institute for collecting, saving, and researching historical evidence about Plovdiv and the surrounding region from 16th to 20th centuries. The exhibition is situated in three buildings.[118]

The Plovdiv Regional Ethnographic Museum was inaugurated in 1917. On 14 October 1943, it was moved to a house in the Old Town. In 1949 the Municipal House-museum was reorganized as a People's Ethnographic Museum and in 1962 it was renovated. There are more than 40,000 objects.[118]

The Museum of Natural Science was inaugurated in 1955 in the old edifice of the Plovdiv Municipality built in 1880. It is among the most important museums in the country with rich collections in its Paleontology, Mineralogy, and Botanic sections. There are several rooms for wildlife and it contains Bulgaria's largest freshwater aquarium with 40 fish species.[118] It has a collection of minerals from the Rhodope mountains.

The Museum of Aviation was established on 21 September 1991 on the territory of the Krumovo airbase[121] 12 km (7 mi) to the southeast of the city. The museum possesses 59 aircraft and indoor and outdoor exhibitions.[118]

The Old Town of Plovdiv is a historic preservation site known for its Bulgarian Renaissance architectural style. The Old Town covers the area of the three central hills (Трихълмие, Trihalmie). Almost every house in the Old Town has its characteristic exterior and interior decoration.

- The Old Town

Balabanov house

Balabanov house Lamartine House

Lamartine House

Klianti House

Klianti House Old town

Old town Street of Old town

Street of Old town.jpg.webp)

Old town

Old town Old town - Plovdiv

Old town - Plovdiv

.jpg.webp) Hindliyan House

Hindliyan House Hisar gate with the ethnographical museum

Hisar gate with the ethnographical museum

Churches, mosques and temples

There are a number of 19th-century churches, most of which follow the distinctive Eastern Orthodox construction style. They are the Saint Constantine and Saint Helena, the Saint Marina, the Saint Nedelya, the Saint Petka, and the Holy Mother of God Churches. As the city has been a gathering center for Orthodox Christians for a long period of time, Plovdiv is surrounded by several monasteries located at the foot of the Rhodope Mountains such as "St. George", "St. Kozma and Damian", St. Kirik, and Yulita (Ulita). They remain good examples of the late Middle Age Orthodox architecture and iconography masterpieces typical for the region. There are also Roman Catholic cathedrals in Plovdiv, the Cathedral of St Louis being the largest. There are several more modern Baptist, Methodist, Presbyterian, and other Protestant churches, as well as older style Apostolic churches.

Two mosques remain in Plovdiv from the time of Ottoman rule. The Djumaya Mosque is considered the oldest European mosque outside Moorish Spain.

The Sephardic Plovdiv Synagogue is at Tsar Kaloyan Street 13 in the remnants of a small courtyard in what was once a large Jewish quarter. Dating to the 19th century, it is one of the best-preserved examples of the so-called "Ottoman-style" synagogues in the Balkans. According to author Ruth E. Gruber, the interior of the Plovdiv Synagogue is a "hidden treasure…a glorious, if run-down, burst of color." An exquisite Venetian glass chandelier hangs from the center of the ceiling, which has a richly painted dome. All surfaces are covered in elaborate, Moorish-style, geometric designs in once-bright greens and blues. Torah scrolls are kept in the gilded Aron-ha-Kodesh.[122]

Culture

Theatre and music

The Plovdiv Drama Theatre[123] is a successor of the first professional theatre group in Bulgaria founded in 1881. The Plovdiv Puppet Theatre, founded in 1948, remains one of the leading institutions in this genre. The Plovdiv Opera was established in 1953.

Another pillar of Plovdiv's culture is the Philharmonic, founded in 1945.[124] Soloists such as Dmitri Shostakovich, Sviatoslav Richter, Mstislav Rostropovich, Yuri Boukov, and Mincho Minchev have worked with the Plovdiv Philharmonic. The orchestra has toured in almost all of the European countries.

The Trakiya Folklore Ensemble, founded in 1974, has performed thousands of concerts in Bulgaria and more than 42 countries.[125] The Trakiya Traditional Choir was nominated for a Grammy Award. The Detska Kitka Choir is one of the oldest and best-known youth choirs in Bulgaria and the winner of numerous awards from international choral competitions. The Evmolpeya choir is another girls' choir from Plovdiv, whose establishing patron, Ivan Chomakov, became the then mayor in 2006. The choir was appointed a Goodwill Ambassador and a municipal choir.

Literature

Plovdiv is among the nation's primary literary centres. In 1855 Hristo G. Danov created the first Bulgarian publishing company and printing-press.[126] The city's traditions as a literary centre are preserved by the first public library in Bulgaria, the Ivan Vazov National Library, the 19 chitalishta (cultural centres), and by numerous booksellers and publishers. The library was founded in 1879[127] and named after the famous Bulgarian writer and poet Ivan Vazov who worked in Plovdiv for five years creating some of his best works.[128] Today the Ivan Vazov National Library is the second largest national library institution with more than 1.5 million books,[129] owning rare Bulgarian and European publications.

Arts

The city has traditions in iconography since the Middle Ages. During the Period of National Revival, a number of notable icon-painters (called in Bulgarian zografi, зографи) from all regions of the country worked in Plovdiv such as – Dimitar Zograf, his son Zafir Zograf, Zahari Zograf, Georgi Danchov, and others.[69] After the Liberation, the Bulgarian painter of Czech origin Ivan Mrkvička came to work in the city. The Painters' Society was established there by artists from southern Bulgaria in 1912 whose members included painters Zlatyu Boyadzhiev, Tsanko Lavrenov and Sirak Skitnik.

Today the city has more than 40 art galleries with most of them being privately owned. The Art Gallery of Plovdiv was founded in the late 19th century.[130] It possesses 5,000 pieces of art in four buildings. Since 1981, it has had a section for Mexican art donated by Mexican painters in honour of the 1,300-year anniversary of the Bulgarian State.

European Capital of Culture

On 5 September 2014, Plovdiv was selected as the Bulgarian host of European Capital of Culture in 2019.[8] The city will co-host the event with Matera and another city (yet to be decided).

After Plovdiv was elected as European Capital of Culture in 2019, an ambitious cultural program has started its realisation. According to this program, there will be an Island of Arts in the middle of the Maritsa River in Plovdiv. The "Kapana" area (the "Trap") will become a quarter of the arts where the creative industries are going to be developed and presented. This famous area, Kapana, was renovated in 2014, restoring its authentic outlook. It has been used for a number of festivals and art events.

For 2019 the City Under the Hills is planning a number of concerts, including "Balkan Music in Plovdiv".The city will host the Plovdiv Biennale and a number of international forums, such as a meeting of collectors from Europe, a summer art school, dance projects, etc.[131]

Economy

GVA by sector (2013)

Employees by sector (2014)

Although it is located in the middle of a rich agricultural region, Plovdiv's economy has shifted from agriculture to industry since the beginning of the 20th century. Food processing, tobacco, brewing, and textiles formed the pillars of the industrial economic shift.[132] During Communist rule, the city's economy expanded and was dominated by heavy industry. After the fall of Communism in 1989 and the collapse of Bulgaria's planned economy, a number of industrial complexes were closed; production of lead and zinc, machinery, electronics, motor trucks, chemicals, and cosmetics have continued.

Plovdiv is the economic capital of Bulgaria as it has the country's largest economy and contributes 7.5% of Bulgaria's GDP as of 2014.[133] In 2014, more than 35 thousand companies operate in the region which create jobs for 285,000 people.[133] The advantages of Plovdiv include the central geographic location, good infrastructure, and large population. Plovdiv has an international airport, terminal for intermodal transport, several connections with Trakia motorway (connecting Sofia and Burgas), proximity to Maritsa motorway (the main corridor to Turkey), and well-developed road and rail infrastructure which all led to the development of the city as the leading city in terms of industrial output in Bulgaria. Established in 1970, the Toplofikatsiya Plovdiv company provides generation of electric power and heat and heat distribution for Plovdiv.[134]

The economy of Plovdiv has long tradition in manufacturing, commerce, transport, communications, and tourism. Apart from the industrial development of Plovdiv, there has been a significant surge in the IT and outsourcing service sector in the recent years, as well as a double-digit increase in the tourism growth in the city every year for the past 5 years.[135]

Economic Indicators

| Indicator | Unit | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | BGN million | 5,539 | 6,062 | 6,178 | 6,374 | 6,273 |

| Share in Bulgaria's GDP | % | 7.5 | 7.6 | 7.6 | 7.8 | 7.5 |

| GDP per capita | BGN | 7,924 | 8,888 | 9,087 | 9,394 | 9,268 |

| Population | Number | 696,300 | 680,884 | 678,860 | 678,197 | 675,586 |

| Average annual number of employees under labor contract | Number | 208,438 | 207,599 | 205,876 | 203,933 | 207,057 |

| Average salary of employees under labor contract | BGN | 6,462 | 6,889 | 7,418 | 7,922 | 8,504 |

| Economic activity rate | % | 64.9 | 64.2 | 67.7 | 70.7 | 71.7 |

| Unemployment rate | % | 8.5 | 8.8 | 11.2 | 13.4 | 13.1 |

| FDI | EUR million | 1.118 | 1.259 | 1.340 | 1.648 | 1.546 |

Source: The National Statistical Institute[133]

Industry

Industry has been the sole leader in attracting investment. Industry has been expanding since the late 1990s, with manufacturing plants being built in the city or in its outskirts mainly the municipality of Maritsa. In this period, some €500,000,000 has been invested in the construction of new factories. Trakia Economic Zone which is one of the largest industrial zones in Eastern Europe, is located around Plovdiv. Some of the biggest companies in the region include the Austrian utility company EVN, PIMK (transport), Insa Oil (fuels), Liebherr (refrigerator plant), Magna International (automotive industry), Bella Bulgaria (food manufacturing), Socotab (tobacco processing), ABB Group, Schneider Electric, Osram, Sensata Technologies, etc.

Shopping and commerce

The commercial sector is developing quickly. Shopping centers have been built mainly in the Central district and the district of Trakiya. Those include Shopping Center Grand,[136] Market Center,[137] and two more all on the Kapitan Raycho Street,[137] Forum in Trakiya, Excelsior, and others. Plovdiv has three large shopping centers: the €40 million Mall of Plovdiv (opened 2009) with a shopping area of 22,000 m2 (236,806.03 sq ft), 11 cinema halls, and parking for 700 cars;[138] Markovo tepe Mall (opened 2016);[139] and Plovdiv Plaza Mall which is 6 stories high with 127 000 m2 area, half of which is the parking lot and the rest is shopping area.

Due to the high demand for business office space, new office and commercial buildings have been built. Several hypermarkets have been built mainly on the outskirts of the city: Metro, Kaufland, Triumf, Praktiker, Billa, Mr. Bricolage, Baumax, Technopolis, Technomarket Europa, and others. The main shopping area is the central street with its shops, cafés, and restaurants. A number of cafés, craftsmen workshops, and souvenir shops are in the Old Town and the small streets in the centre, known among the locals as "The Trap" (Bulgarian: Капана).

The Plovdiv International Fair, held annually since 1892, is the largest and oldest fair in the country and all of southeastern Europe, gathering companies from all over the world in an exhibition area of 138,000 m2 (1,485,419.64 sq ft) located on a territory of 352,000 m2 (3,788,896.47 sq ft) on the northern banks of the Maristsa river.[140] It attracts more than 600,000 visitors from many countries.[141]

The city has had a duty-free zone since 1987. It has a customs terminal handling cargo from trucks and trains.[141]

Mall Plovdiv Plaza

Mall Plovdiv Plaza Mall Markovo tepe

Mall Markovo tepe Mall Plovdiv

Mall Plovdiv Forum Trakia shopping center

Forum Trakia shopping center

Transport

Plovdiv's geographical position makes it an international transport hub. Three of the ten Pan-European corridors run into or near the city: Corridor IV (Dresden–Bucharest–Sofia-Plovdiv-Istanbul), Corridor VIII (Durrës-Sofia-Plovdiv-Varna/Burgas), and Corridor X (Salzburg–Belgrade-Plovdiv-Istanbul).[142][143] A major tourist centre, Plovdiv lies at the foot of the Rhodope Mountains, and most people wishing to explore the mountains choose it as their trip's starting point.

The city is a major road and railway hub in southern Bulgaria with[144] the Trakia motorway (A1) only 5 km (3 mi) to the north. It lies on the important national route from Sofia to Burgas via Stara Zagora. First-class roads lead to Sofia to the west, Karlovo to the north, Asenovgrad, Kardzhali to the south, and Stara Zagora and Haskovo to the east. There are intercity buses which link Plovdiv with cities and towns all over the country and many European countries. They are based in three bus stations: South, Rodopi, and North.

Railway transport in the city dates back to 1872 when it became a station on the Lyubimets–Belovo railway line. There are railway lines to Sofia, Panagyurishte, Karlovo, Peshtera, Stara Zagora, Dimitrovgrad, and Asenovgrad. There are three railway stations: – Plovdiv Central, Trakia, and Filipovo – as well as a freight station.[142]

Plovdiv has a large public transport system[145] including around 29 main and 10 extra bus lines. However, there are no trams in the city, and the Plovdiv trolleybus system was closed in autumn 2012.[146] Six bridges span the Maritsa river including a railway bridge and a covered bridge. There are important road junctions to the south, southwest, and north.

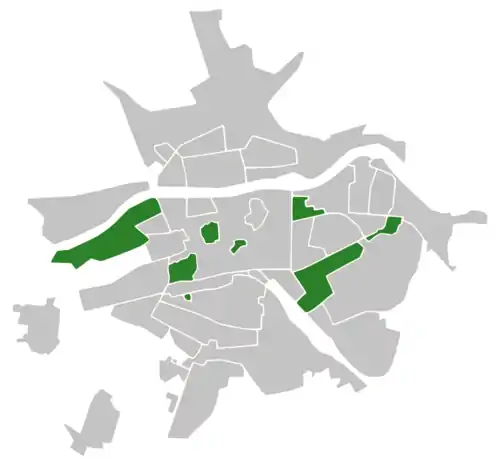

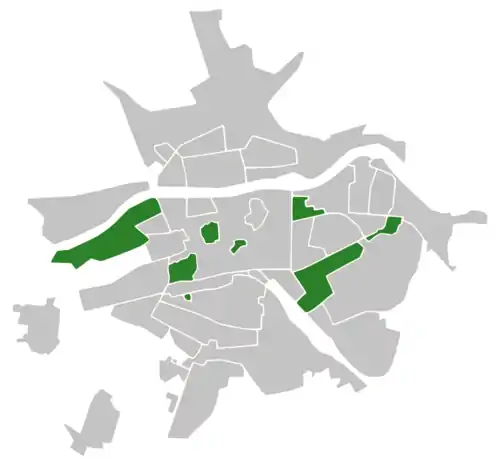

Plovdiv has a well-developed cycling infrastructure which covers almost all districts of the city. The total length of the cycling roads is 60 kilometres (37 miles) (48 kilometres (30 miles) are completed and 12 kilometres (7.5 miles) are under construction). The city has a total of 690 bike parkings.

- Cycling Infrastructure

The number of registered private automobiles in the city increased from 178,104 in 2005 to 234,298 in 2009.[147] There are around 658 cars per 1,000 inhabitants[148]

The Plovdiv International Airport is near the village of Krumovo, 5 km (3 mi) southeast of the city. It takes charter flights from Europe and has scheduled services with Ryanair to London Stansted and Dublin and S7 to Moscow. Wizz Air have services to London Luton, Dortmund, and Munich West.Many small airports are in the city's surroundings, including the Graf Ignatievo Air Base in Graf Ignatievo to the north of Plovdiv.

The BIAF Airshow is held every two years on the Krumovo airbase and is one of the biggest airshows in the Balkans.

Education

Around two thirds of the citizens (62,38%) have secondary, specialized, or higher education. That percentage increased from 1992 to 2001.[149]

Plovdiv has 78 schools including elementary, high, foreign language, mathematics, technical, and art schools. There are also 10 private schools and a seminary. The number of pupils in 2005 was 36,964 and has been constantly decreasing since the mid-1990 due to lower birth rate.[149] Among the most prestigious schools are the English Language School, the High School of Mathematics, the Ivan Vazov Language School, the National Schools of Commerce – Plovdiv,[150] the English Academy,[151] the Academy of Music, Dance and Fine Arts Plovdiv,[152] and the French High School of Plovdiv.[153]

The city has six universities and a number of state and private colleges and branches of other universities. Those include Plovdiv University,[154] with 900 lecturers and employees and 13,000 students; the Plovdiv Medical University, with 2,600 students;[155] the Medical College; the Technical University of Sofia – Branch Plovdiv;[156] the Agricultural University – Plovdiv;[157] the University of Food Technologies;[158] the Academy for Music, Dance and Fine Arts;[159] and others.[149]

The 2009 International Olympiad in Informatics (IOI) was held at the University of Plovdiv "Paisiy Hilendarski", between 8 and 15 August 2009. The 2009 IOI Honorary Patron was Bulgarian President Georgi Parvanov.

Between 1875 and 1906, the Zariphios School was one of the local Greek educational institutions that provided elementary and secondary education.[160]

Sports and recreation

Plovdiv Sports Complex consists of Plovdiv Stadium with several additional football fields, tennis courts, swimming pools, a rowing base with a 2 km-long channel, restaurants, and cafés in a spacious park in the western part of the city just south of the Maritsa river. There are also playgrounds for children. It is popular among the citizens and guests of Plovdiv who use it for jogging, walking, and relaxation. Plovdiv Stadium (55,000 seats) is the largest football venue in Bulgaria.[161]

Other stadiums include Stadion Botev, Lokomotiv (10,000 seats), Maritsa Stadium (5,000 seats), and Todor Diev Stadium (7,000 seats). There are seven indoor sports halls: Kolodruma, University Hall, Olimpia, Lokomotiv, Dunav, Stroitel, Chaika, Akademik, and Total Sport. In 2006, Aqualand, a water park, was opened near the city centre.[162] Several smaller water parks are in the city as well.

- Sport Facilities

Plovdiv Stadium and sport complex

Plovdiv Stadium and sport complex Rowing base

Rowing base

Plovdiv University sports hall

Plovdiv University sports hall

Football is the most popular sport in the city; Plovdiv has three professional teams. The city has PFC Botev Plovdiv, founded in 1912 and PFC Lokomotiv, founded in 1926.[163] Both teams are a regular fixture in the top Bulgarian league. The rivalry between them is considered to be even more fierce than the one between Levski and CSKA of Sofia. There are two other football clubs in the city – Maritsa FC (founded in 1921) and Spartak Plovdiv (1947).[164]

Plovdiv is host of the international boxing tournament "Strandzha" which has taken place since 1949.[165] In 2007, 96 boxers from 20 countries participated in the tournament. There is a horse racing club and a horse base near the city. Plovdiv has several volleyball and basketball teams.

Three of the city's seven hills are protected natural territories since 1995. Two of the first parks in Bulgaria are located in the city center – Tsar Simeon garden – city garden, where the very first work of the Italian sculptor Arnoldo Zocchi could be seen, and Dondukov garden – old city garden. Some of the larger parks include the Botanical garden, Beli Brezi, Ribnitsa, and Lauta.

Notable people

- Ahmad Hilmi of Filibe – (1865–1914), writer, thinker

- Ivan Andonov – (1934–2011), actor

- Vladimir Arabadzhiev – (born 1984), racing driver

- Zlatyu Boyadzhiev – (1903–1976), painter

- Boris Christoff – (1914–1993), basso

- Hristo G. Danov – (1828–1911), publisher

- Dimcho Debelyanov – (1887–1916), writer

- Samuel Finzi – (born 1966), German actor

- George Ganchev – (1939–2019), actor, writer, politician and fencer

- Nayden Gerov – (1823–1900), linguist, folklorist and writer

- Ivan Evstratiev Geshov – (1849–1924), former Prime Minister of Bulgaria

- Todor Kableshkov – (1851–1876), a 19th-century Bulgarian revolutionary

- Petko Karavelov – (1843–1903), revolutionary and former Prime Minister of Bulgaria

- Asen Kisimov – (1936–2005), actor

- Georgios Kleovoulos – (ca.1785-1828), Greek scholar and educator

- Antonios Komizopoulos – (19th.C.), Greek merchant and the 4th member of Filiki Eteria

- Milcho Leviev – (1937–2019), musician

- Andrey Lyapchev – (1866–1933), former Prime Minister of Bulgaria

- Aleksandar Malinov – (1867–1938), former Prime Minister of Bulgaria

- Stoika Milanova – (born 1945), classical violinist

- Ivan Mrkvička – (1856–1938), painter

- Sava Mutkurov – (1852–1891), former Regent of Bulgaria, the chief architect of the Bulgarian unification

- Kiril Petkov – (born 1980), acting Prime Minister of Bulgaria

- Silvena Rowe – (born 1967), British chef, food writer, TV personality and restaurateur

- Nanka Serkedzhieva – (1925–2012), female military officer

- Pencho Slaveykov – {1866–1912), writer and poet

- Konstantin Stoilov – (1853–1901), former Prime Minister of Bulgaria

- Petar Stoyanov – (born 1952), former President of Bulgaria

- Slavik Tabakov – medical physicist, President IOMP

- Emma Tahmizian – (born 1957), pianist

- Nayden Todorov – (born 1974), conductor

- Christos Tsigiridis – (1877-1947), Greek electrical engineer and technological pioneer

- Ivan Vazov – (1850–1921), writer

- Zhan Videnov – (born 1959), former Prime Minister of Bulgaria

- Angel Wagenstein (1922-2023), screenwriter and author

- Sonya Yoncheva – (born 1981), opera singer

- Yordan Yovkov – (1880–1937), writer

Sport

- Miroslav Barnyashev – (born 1984), professional wrestler, performing under the name of Miro

- Georgi Hristov – (born 1985), former professional footballer

- Stefka Kostadinova – (born 1965), world-record holder in the women's high jump

- Apostolos Nikolaidis – (1896–1980), Greek athlete

- Tsvetana Pironkova – (born 1987), professional tennis player

- Iva Prandzheva – (born 1972), long jumper and triple jumper

- Hristo Stoichkov – (born 1966), football player

- Serafim Todorov – (born 1969), boxer

- Yordan Yovchev – (born 1973), gymnast

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

Bursa, Turkey

Bursa, Turkey Changchun, China

Changchun, China Columbia, United States

Columbia, United States Daegu, South Korea

Daegu, South Korea Donetsk, Ukraine

Donetsk, Ukraine Gyumri, Armenia

Gyumri, Armenia Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Istanbul, Turkey

Istanbul, Turkey Ivanovo, Russia

Ivanovo, Russia Kastoria, Greece

Kastoria, Greece Košice, Slovakia

Košice, Slovakia Kumanovo, North Macedonia

Kumanovo, North Macedonia Kutaisi, Georgia

Kutaisi, Georgia Leskovac, Serbia

Leskovac, Serbia Luoyang, China

Luoyang, China Ohrid, North Macedonia

Ohrid, North Macedonia Okayama, Japan

Okayama, Japan Petra, Jordan

Petra, Jordan Rome, Italy

Rome, Italy Saint Petersburg, Russia

Saint Petersburg, Russia Samarkand, Uzbekistan

Samarkand, Uzbekistan Shenzhen, China

Shenzhen, China Thessaloniki, Greece

Thessaloniki, Greece Valencia, Venezuela

Valencia, Venezuela Yekaterinburg, Russia

Yekaterinburg, Russia

Honour

The asteroid (minor planet) 3860 Plovdiv is named after the city. It was discovered by the Belgian astronomer Eric W. Elst and the Bulgarian astronomer Violeta G. Ivanova on 8 August 1986. Plovdiv Peak (1,040 m or 3,412 ft) on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica, is also named after Plovdiv.

Gallery

A panoramic view

A panoramic view Looking down one of the streets in Plovdiv.

Looking down one of the streets in Plovdiv. Plan of the medieval fortress

Plan of the medieval fortress

See also

References

- "Population and Demographic Processes in 2014 (Final data) – National statistical institute". www.nsi.bg. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "Functional Urban Areas – Population on 1 January by age groups and sex". Eurostat. 1 April 2016. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- "Population on 1 January by broad age group, sex and metropolitan regions". eurostat.ec. Eurostat. 8 October 2017. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

- History (Plovdiv) Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Official website in English

- Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (2012), Hornblower, Simon; Spawforth, Antony; Eidinow, Esther (eds.), "Philippopolis", The Oxford Classical Dictionary (4th ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-954556-8, archived from the original on 29 May 2021, retrieved 27 December 2020

- Kazhdan, Alexander P. (2005) [1991], Kazhdan, Alexander P. (ed.), "Philippopolis", The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6, archived from the original on 29 May 2021, retrieved 27 December 2020

- Rizos, Efthymios (2018), Nicholson, Nicholson (ed.), "Philippopolis", The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780198662778.001.0001, ISBN 978-0-19-866277-8, archived from the original on 6 December 2020, retrieved 27 December 2020

- "Plovdiv to be 2019 European Capital of Culture in Bulgaria". Official website of the European Union. Archived from the original on 6 September 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Arch museum Archived 27 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Odrison Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Topalilov, Ivo (10 December 2014). "Philippopolis, Thrace (I-VII c.) - Ivo Topalilov - Academia.edu". Archived from the original on 10 December 2014.

- "Index". Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- "Strabo, Geography, Book 7, chapter 6". Archived from the original on 26 February 2015. Retrieved 4 June 2016. 32 quote

- "Plutarch, de curiositate, section 10". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- "Plovdiv". The Columbia Encyclopedia (6th ed.). Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- Kamen Kolev Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Strabo, Geography VII.6.2 Archived 28 September 2023 at the Wayback Machine (see the original Greek Archived 2 June 2021 at the Wayback Machine).

- Ἀπόλλωνι Κενδρισῳ Βειθυς Κοτυος ἱερεὺς Συρίας θεᾶς δῶρον ἀνε-

- "CNG-Ancient Greek, Roman, British Coins". Archived from the original on 6 August 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- "De re nummaria antiqua, opera quae extant universa - Hubertus Goltzius - Google Books". Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016."Ammianus Marcellinus - Google ブックス". Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- Mikalson, Jon D. (2010). Ancient Greek religion (2nd ed.). Chichester, West Sussex, U.K.: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4443-5819-3.

...whose champion was the Thracian Eumolpus, a son of Poseidon.

- "A Classical Dictionary". 1831. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- Ortiz, Alicia Morales; Cánovas, Cristóbal Pagán; Campillo, Carmen Martínez, eds. (2010). The Teaching of Modern Greek in Europe. EditumM. p. 64. ISBN 978-84-8371-938-1. Archived from the original on 19 August 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- Raĭchevski, Georgi (2002). "Plovdiv Encyclopedia". Archived from the original on 29 May 2021. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- "Plovdiv | Bulgaria". Archived from the original on 28 February 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2015.

- "The Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, PACHIA AMMOS ("Minoa") Ierapetra district, Crete., PHAISTOS Kainourgiou, Crete., PHILIPPOPOLIS or Eumolpia or Trimontium (Plovdiv) Bulgaria". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Archived from the original on 7 January 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- Dragostinova, Theodora (2011). "underline remark # 47". Between Two Motherlands: Nationality and Emigration Among the Greeks of Bulgaria, 1900–1949. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4945-1. Archived from the original on 29 May 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2020.

- Куцаров, Иван (2002). Славяните и славянската филология: очерк по история на славистиката и булгаристиката от втората половина на XIX до началото на XXI век. Пловдивско унивєрситєтско изд-во. ISBN 978-954-423-244-3. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2022.

- avtori Evgeni Dinchev ...; et al. (2002). Пътеводител България (in Bulgarian). София: ТАНГРА ТанНакРа ИК. p. 145. ISBN 954-9942-32-5.

- "Седемте чудеса на България – Пловдив". Milarodino.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 7 January 2011.

- Общински план за развитие на Пловдив 2005 – 2013 г. Archived 14 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, посетен на 10 ноември 2007 г.

- Cappelen, John; Jensen, Jens. "Bulgarien – Plovdiv" (PDF). Climate Data for Selected Stations (1931–1960) (in Danish). Danish Meteorological Institute. p. 42. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- "Philippopolis Album", Kesyakova Elena, Raytchev Dimitar, Hermes, Sofia, 2012, ISBN 978-954-26-1117-2

- Райчевски, Георги (2002). Пловдивска енциклопедия. Пловдив: Издателство ИМН. p. 341. ISBN 978-954-491-553-7.

- Кесякова, Елена; Александър Пижев; Стефан Шивачев; Недялка Петрова (1999). Книга за Пловдив (in Bulgarian). Пловдив: Издателство "Полиграф". pp. 17–19. ISBN 954-9529-27-4.

- Darik Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Детев П., Известия на музейте в Южна България т. 1 (Bulletin des musees de la Bulgarie du sud), 1975г., с.27, ISSN 0204-4072 Archived 23 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Детев, П. Разкопки на Небет тепе в Пловдив, ГПАМ, 5, 1963, pp. 27–30.

- Ботушарова, Л. Стратиграфски проучвания на Небет тепе, ГПАМ, 5, 1963, pp. 66–70.

- Елена Кесякова; Александър Пижев; Стефан Шивачев; Недялка Петрова (1999). Книга за Пловдив (in Bulgarian). Пловдив: Издателство "Полиграф". pp. 20–21. ISBN 954-9529-27-4.

- The Oxford Classical Dictionary by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth, ISBN 0-19-860641-9", page 1515, "The Thracians were subdued by the Persians by 516"

- Dimitri Romanoff, The orders, medals, and history of the Kingdom of Bulgaria, p. 9

- История на България, Том 1, Издателство на БАН, София, 1979, p. 206.

- A. B. Bosworth, Conquest and Empire: The Reign of Alexander the Great, page 12, Cambridge University Press

- Bulgaria. University of Indiana. 1979. p. 4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Dimitrov, B. (2002). The Bulgarians – the first Europeans (in Bulgarian). Sofia: University press "St Climent of Ohrid". p. 17. ISBN 954-07-1757-4.

- Lenk, B. – RE, 6 A, 1936 col. 454 sq.

- Римски и ранновизантийски градове в България, p. 183