1st Texas Field Battery

1st Texas Field Battery or Edgar's Company was an artillery battery from Texas that served in the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War. The artillery company formed in November 1860, but was not formally taken into Confederate service until April 1861. The unit participated in the disarming and surrender of United States soldiers and property in Texas in early 1861. The battery marched to Arkansas where in 1862 it joined the infantry division known as Walker's Greyhounds. The battery fought at Milliken's Bend and Richmond (La.), shelled a Federal river transport, and campaigned in south Louisiana in late 1863. The 1st Texas Battery was captured at Henderson's Hill in March 1864. The soldiers were later exchanged, and the unit disbanded in 1865 at the end of the conflict.

| 1st Texas Field Battery | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) In March 1864, the battery included two 12-pounder howitzers, Model 1841 (as shown). | |

| Active | April 20, 1861 – June 2, 1865 |

| Country | Confederate States of America |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Field Artillery |

| Size | Artillery Battery |

| Nickname(s) | Edgar's Company |

| Equipment | 2 x M1841 12-pounder howitzers 2 x M1841 6-pounder field guns (Mar. 1864) |

| Engagements |

|

| Commanders | |

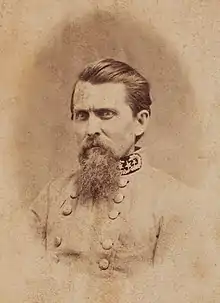

| Notable commanders | William Edgar |

Formation and early service

The battery was first organized in November 1860 by Captain William Edgar. The unit consisted of 49 men recruited from the San Antonio area. On February 15, 1861, the battery joined an armed force led by Benjamin McCulloch which gathered outside San Antonio. The next day, the force marched into the city with the purpose of confiscating United States government supplies and munitions. In response, Major General David E. Twiggs surrendered government property and ordered Federal troops to evacuate Texas. Edgar's battery was detailed to guard the arsenal, acquiring the nickname "Alamo City Guards". On April 20, 1861, Colonel Earl Van Dorn mustered the battery into Confederate service with the designation Edgar's Company A, Texas Light Artillery. The unit counted about 60 men and was armed with four artillery pieces. The battery was ordered to march to Matagorda Bay, but before it reached there it was recalled to help resolve a crisis. Federal troops led by Lieutenant Colonel Isaac Reeve refused to be disarmed. Edgar's Battery marched to Castroville to join forces with Van Dorn's troops. Reeves finally surrendered his outnumbered command without bloodshed.[1]

Service

1861–1862

Edgar was ordered to prepare the battery to be transferred to northeast Texas. He attempted to recruit the company up to 100 soldiers, but before he could do so, the unit was ordered to the junction of the Red and Washita Rivers. When the battery got there, it was ordered to turn around and march to Harrisburg. Along the march, Edgar recruited soldiers for his battery. In September 1861, Edgar's battery moved from Harrisburg to Galveston where it spent the winter. While in Galveston, the battery increased the number of artillery pieces to six. Edgar was unable to fully recruit the battery because the soldiers had enlisted for a term of one year, and some men declined to re-enroll. In April 1862, the battery was assigned to Waul's Legion under the command of Brigadier General Thomas N. Waul. During this period, Edgar's battery was stationed at Camp Waul,[1] located at Old Gay Hill in Washington County, where it endured a severe measles outbreak.[2]

Edgar's battery was ordered to march to Arkansas, where it arrived at Camp Nelson in September 1862.[1] Brigadier General Henry Eustace McCulloch organized a Texas infantry division at the camp which consisted of four brigades, each with an attached artillery battery. While at Camp Nelson, 1,500 Confederate soldiers died from dysentery and other maladies due largely to tainted water.[3] Edgar's Battery was assigned to the 3rd Brigade, commanded by Colonel George Flournoy. The 3rd Brigade also included the 16th Texas Infantry, 17th Texas Infantry, and 19th Texas Infantry Regiments, and the 16th Texas Cavalry Regiment (Dismounted). In 1863, the officers in Edgar's Battery were Captain Edgar, First Lieutenants James M. Ransom and John D. Grumbas, Second Lieutenants Henry Hall and Nicholas R. Gomey, and Assistant Surgeon T. C. Thompson. The division's 4th Brigade was soon detached and captured at Arkansas Post.[4][note 1]

On November 24, 1862, the Texas infantry division left Camp Nelson to march to Bayou Meto where it remained until December 13. Subsequently, the division marched to Little Rock where it spent December 25 in camp. The next day, Major General John George Walker assumed command of the division and McCulloch replaced Flournoy as commander of the 3rd Brigade. The division received new orders to march to Pine Bluff.[5] The division later became known as Walker's Greyhounds.[6]

1863

Walker's division arrived in Pine Bluff on January 8, 1863, but three days later it began marching toward Arkansas Post to relieve its garrison. When news arrived that Arkansas Post surrendered, the division camped on the bank of the Arkansas River in bitterly cold weather.[7] Walker's division returned to Pine Bluff on January 20 where it went into winter quarters, only emerging on April 23 when it marched to Monroe, Louisiana.[8] From there, the troops marched to Campti, then traveled by riverboat to Alexandria, arriving on May 27.[9] The division then marched and took river transports to a point on the Mississippi River called Perkins' Landing which was south of Vicksburg, Mississippi. When Walker's division arrived on May 31, the Union soldiers withdrew behind the levee and several gunboats began shelling the Confederates. In the action, Edgar's 1st Texas Field Battery fired 96 rounds at the Federal gunboats and troops. During the 80-minute bombardment, the Union soldiers boarded river transports and evacuated the position.[10][note 2]

After the affair at Perkins' Landing, Walker's division began marching to Richmond, Louisiana, arriving on June 6, 1863. McCulloch's brigade was ordered to assault Milliken's Bend while a second brigade attacked Young's Point and a third brigade was held back as a reserve.[11] Milliken's Bend was held by Union Colonel Hermann Lieb's four regiments of newly recruited African-Americans, former slaves, and two companies of the 10th Illinois Cavalry Regiment. Lieb led a reconnaissance toward Richmond on June 6 which encountered Confederate cavalry, so he asked his superior for help. The gunboats USS Choctaw and USS Lexington and the weak 23rd Iowa Infantry Regiment, a white unit, were sent to Lieb's assistance. In the Battle of Milliken's Bend on June 7, McCulloch's 1,500 men attacked approximately 1,000 Union soldiers. The poorly-trained former slaves fired a volley which mostly missed, then McCulloch's soldiers rushed into them. Unable to reload, many of the African-Americans fought with bayonets and clubbed muskets before retreating. Once the Union survivors fell back to the riverbank, the gunboats' fire stopped the Confederates and eventually led Walker to abandon the attack.[12] Union casualties were 652 while Confederate losses numbered only 185.[13]

Walker's division retreated to Richmond where it camped until June 15, when it was attacked by Union forces in the Battle of Richmond. Walker ordered Edgar's Battery and the 18th Texas Infantry Regiment led by Colonel D. B. Culbertson to defend a position behind Roundaway Bayou and hold off the Federals while the division's wagon train made its escape. When the leading Union troops got within 150 yd (137 m), the 18th Texas and the battery opened fire, causing their closest attackers to run away. The 18th Texas crossed the bayou in pursuit, and when the Union soldiers rallied in a nearby woods, Culbertson ordered his men to return to their original position. Walker withdrew his division from Richmond; the Union pursuit ended at Bayou Macon.[14] The Federals were led by Brigadier General Joseph A. Mower and included his own brigade and Brigadier General Alfred W. Ellet's Mississippi Marine Brigade. Mower reported that his leading unit, the 5th Minnesota Infantry Regiment came into action and lost 1 man killed and 8 wounded.[15]

In July 1863, Walker's division traveled back to Monroe, followed by a move to Campti.[16] In October, the division opposed a Union expedition near Washington in south Louisiana. Lieutenant General Richard Taylor concentrated 11,000 troops including Edgar's, Daniel's, Haldeman's, and the Val Verde Texas batteries and Semmes' Louisiana Battery.[17] On November 18, Edgar's, Daniel's, and Haldeman's Texas batteries and Semmes' and West's Louisiana batteries ambushed the Union transport Black Hawk at the mouth of the Red River, badly injuring it.[18] In mid-December, the 3rd Brigade, now under Brigadier General William R. Scurry, camped at the Norwood Plantation near Simmesport,[19] guarding the bridge over the Atchafalaya River.[1]

1864–1865

On March 10, 1864, Federal forces under Major General Nathaniel P. Banks launched the Red River campaign which was designed to open a corridor along the Red River to Texas. Banks moved north along Bayou Teche with 17,000 troops while Major General Andrew Jackson Smith moved up the Red River with 10,000 soldiers, supported by a Union gunboat fleet. On March 14, Smith's column stormed Fort De Russy. On March 18 Smith occupied Alexandria while Taylor's Confederate forces retreated.[20] On March 19, Taylor sent the 2nd Louisiana Cavalry Regiment under Colonel William G. Vincent to observe the Union forces at Alexandria. The next day he sent Edgar's 1st Texas Field Battery to support Vincent. Early on March 21, Mower led a Federal task force from Alexandria consisting of two infantry brigades, a cavalry regiment, and an artillery battery from Smith's column. At nightfall, after marching through heavy rain, Mower's force reached Henderson's Hill where Vincent's troops were posted. Hearing of Vincent's predicament, Taylor sent a staff officer with orders authorizing Vincent to retreat toward the main Confederate force.[21]

In the Battle of Henderson's Hill, Mower deployed one part of his force in front of the hill while sending a second part on a trek through swamps to gain the rear of Vincent's camp. Having gotten the Confederate countersign from pro-Union citizens, the Federal flanking column silently captured the Confederate pickets and moved into Vincent's camp. The surprise was complete and Edgar's battery and over 200 men became Union prisoners.[22] Smith's official report stated that his troops took two M1841 12-pounder howitzers, two M1841 6-pounder field guns, and four caissons. The report listed the captured as 4 officers and 45 men from Edgar's Texas Battery, 15 officers and 192 men from the 2nd Louisiana, and 5 others including Taylor's staff officer, for a total of 22 officers and 239 men captured.[23] Mower's force returned to Alexandria the next day.[24]

The prisoners from Edgar's battery were held at New Orleans and released on July 22, 1864, at Red River Landing after a prisoner exchange. Afterward, the 1st Texas Field Battery served in the Red River area. In September 1864 the unit was assigned to the 8th Mounted Artillery Battalion. The battery went into winter quarters at Natchitoches and in early 1865 it returned to Texas. When it was clear that the war was over, the men went home. The 1st Texas Field Battery was included in the official list of surrendered units on June 2, 1865. Officers who served with the battery who were not mentioned above were Captain J. M. Salter, First Lieutenant W. S. Good, and Second Lieutenants Horace Grace, Frederick Luck, and Newton Squire.[1]

Notes

- Footnotes

- Blessington referred to the officers as J. M. Ransom, John D. Grumbas, H. Hall, and N. R. Gomey. Jeffrey referred to them as James M. Ransom, John D. Gumbs, Henry Hall, and Nicholas R. Going.

- The sources did not give the date when Edgar's Battery was designated the 1st Texas Field Battery.

- Citations

- Jeffrey 2011.

- Christian 1994.

- Blessington 1875, pp. 44–45.

- Blessington 1875, pp. 54–59.

- Blessington 1875, pp. 61–65.

- Blessington 1875, p. 46.

- Blessington 1875, pp. 66–71.

- Blessington 1875, pp. 75–78.

- Blessington 1875, p. 83.

- Blessington 1875, pp. 86–90.

- Blessington 1875, pp. 93–94.

- Dobak 2011, pp. 178–184.

- Foote 1986, p. 406.

- Blessington 1875, pp. 110–111.

- Official Records 1889, pp. 451–452.

- Blessington 1875, pp. 127–128.

- Blessington 1875, p. 135.

- Blessington 1875, pp. 150–151.

- Blessington 1875, p. 158.

- Boatner 1959, pp. 685–686.

- Brooksher 1998, pp. 54–55.

- Brooksher 1998, p. 55.

- Official Records 1891, p. 314.

- Brooksher 1998, p. 56.

References

- Blessington, Joseph P. (1875). "The Campaigns of Walker's Texas Division". New York, N.Y.: Lange, Little & Co. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1959). The Civil War Dictionary. New York, N.Y.: David McKay Company Inc. ISBN 0-679-50013-8.

- Brooksher, William Riley (1998). War Along the Bayous: The 1864 Red River Campaign in Louisiana. Washington, D.C.: Brassey's. ISBN 1-57488-139-6.

- Christian, Carole E. (1994). "Camp Waul". Handbook of Texas. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- Dobak, William A. (2011). "Freedom by the Sword: The U.S. Colored Troops 1862–1867" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, U.S. Army. p. 193. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- Foote, Shelby (1986) [1963]. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y.: Random House. ISBN 0-394-74621-X.

- Jeffrey, Britney (2011). "First Texas Field Battery Light Artillery". Handbook of Texas. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- Official Records (1889). "The War of the Rebellion; A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Volume XXIV, Part II". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- Official Records (1891). "The War of the Rebellion; A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies: Volume XXXIV Part I". Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Retrieved January 16, 2023.

Further reading

- Cobb, D. Michael Jr. (1999). "First Texas Field Battery, CSA". Lamar County, Texas. Retrieved January 12, 2023.

- Coffey, Walter (2019). "Red River: The Henderson's Hill Engagement". The Civil War Months. Retrieved January 12, 2023.