365 Crete earthquake

The 365 Crete earthquake occurred at about sunrise on 21 July 365 in the Eastern Mediterranean,[4][5] with an assumed epicentre near Crete.[6] Geologists today estimate the undersea earthquake to have been a moment magnitude 8.5 or higher.[5] It caused widespread destruction in the central and southern Diocese of Macedonia (modern Greece), Africa Proconsularis (northern Libya), Egypt, Cyprus, Sicily,[7] and Hispania (Spain).[8] On Crete, nearly all towns were destroyed.[5]

Constantinople Tripoli Alexandria | |

| Local date | 21 July 365 |

|---|---|

| Local time | Sunrise |

| Magnitude | Mw 8.5+[1] |

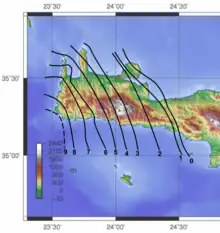

| Epicenter | near Crete 35.0°N 23.0°E[2] |

| Fault | Unknown (HSZ) |

| Areas affected | Mediterranean Basin |

| Max. intensity | XI (Extreme)[2] |

| Tsunami | Yes |

| Casualties | "many thousands"[2][3] |

The earthquake was followed by a paleotsunami which devastated the southern and eastern coasts of the Mediterranean, particularly Libya, Alexandria, and the Nile Delta, killing thousands and hurling ships 3 km (1.9 mi) inland.[3] The quake left a deep impression on the late antique mind, and numerous writers of the time referred to the event in their works.[9]

Geological evidence

Recent (2001) geological studies view the 365 Crete earthquake in connection with a clustering of major seismic activity in the Eastern Mediterranean between the fourth and sixth centuries which may have reflected a reactivation of all major plate boundaries in the region.[5] The earthquake is thought to be responsible for an uplift of nine metres (30 feet) of the island of Crete, which is estimated to correspond to a seismic moment of 1×1022 N⋅m (7.4×1021 lbf⋅ft), or 8.6 on the moment magnitude scale. An earthquake of such a size exceeds all modern ones known to have affected the region.[5]

Carbon dating shows that corals on the coast of Crete were lifted ten metres (33 feet) and clear of the water in one massive push. This indicates that the tsunami of 365 was generated by an earthquake in a steep fault in the Hellenic Trench near Crete. Scientists estimate that such a large uplift is likely to occur only once in 5,000 years; however, the other segments of the fault could slip on a similar scale—and this could happen every 800 years or so. It is uncertain whether "one of the contiguous patches might slip in the future."[10][11]

Sedimentation increased dramatically in some areas of the Mediterranean Sea, while other areas had coastal sediments moved to deep waters.[12]

Literary evidence

Historians continue to debate whether ancient sources refer to a single catastrophic earthquake in 365, or whether they represent a historical amalgamation of a number of earthquakes occurring between 350 and 450.[13] The interpretation of the surviving literary evidence is complicated by the tendency of late antique writers to describe natural disasters as divine responses or warnings to political and religious events.[14] In particular, the virulent antagonism between rising Christianity and paganism at the time led contemporary writers to distort the evidence. Thus, the Sophist Libanius and the church historian Sozomenus appear to conflate the great earthquake of 365 with other lesser ones to present it as either divine sorrow or wrath—depending on their viewpoint—for the death of Emperor Julian, who had tried to restore the pagan religion two years earlier.[15]

On the whole, however, the relatively numerous references to earthquakes in a time which is otherwise characterized by a paucity of historical records strengthens the case for a period of heightened seismic activity.[16] Kourion on Cyprus, for example, is known to have been hit then by five strong earthquakes within a period of eighty years, leading to its permanent destruction.[17]

Archeology

Archeological evidence for the particularly devastating effect of the 365 earthquake is provided by a survey of excavations which document the destruction of most late antique towns and cities in the Eastern and Southern Mediterranean around 365.[7]

Tsunami

The Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus described in detail the tsunami that hit Alexandria and other places in the early hours of 21 July 365.[3] His account is particularly noteworthy for clearly distinguishing the three main phases of a tsunami, namely an initial earthquake, the sudden retreat of the sea and an ensuing gigantic wave rolling inland:

Slightly after daybreak, and heralded by a thick succession of fiercely shaken thunderbolts, the solidity of the whole earth was made to shake and shudder, and the sea was driven away, its waves were rolled back, and it disappeared, so that the abyss of the depths was uncovered and many-shaped varieties of sea-creatures were seen stuck in the slime; the great wastes of those valleys and mountains, which the very creation had dismissed beneath the vast whirlpools, at that moment, as it was given to be believed, looked up at the sun's rays. Many ships, then, were stranded as if on dry land, and people wandered at will about the paltry remains of the waters to collect fish and the like in their hands; then the roaring sea as if insulted by its repulse rises back in turn, and through the teeming shoals dashed itself violently on islands and extensive tracts of the mainland, and flattened innumerable buildings in towns or wherever they were found. Thus in the raging conflict of the elements, the face of the earth was changed to reveal wondrous sights. For the mass of waters returning when least expected killed many thousands by drowning, and with the tides whipped up to a height as they rushed back, some ships, after the anger of the watery element had grown old, were seen to have sunk, and the bodies of people killed in shipwrecks lay there, faces up or down. Other huge ships, thrust out by the mad blasts, perched on the roofs of houses, as happened at Alexandria, and others were hurled nearly two miles from the shore, like the Laconian vessel near the town of Methone which I saw when I passed by, yawning apart from long decay.[18]

The tsunami in 365 was so devastating that the anniversary of the disaster was still commemorated annually at the end of the sixth century in Alexandria as a "day of horror".[19][10]

Gallery

Effects of the earthquake visible in the ancient remains:

Raised beach 2 km west of Paleochora (Crete) showing wave-cut notch and sea caves uplifted by about 9 m during the earthquake

Raised beach 2 km west of Paleochora (Crete) showing wave-cut notch and sea caves uplifted by about 9 m during the earthquake Sea advanced close to the baths at Sabratha (Libya)

Sea advanced close to the baths at Sabratha (Libya).JPG.webp) Submerged harbors at Apollonia (Libya)

Submerged harbors at Apollonia (Libya) The no-longer-submerged harbor in Phalasarna (Crete)

The no-longer-submerged harbor in Phalasarna (Crete)

See also

Footnotes

- Stiros, S. C. (2010). "The 8.5+ magnitude, AD365 earthquake in Crete: Coastal uplift, topography changes, archaeological and historical signature". Quaternary International. 216 (1–2): 54–63. Bibcode:2010QuInt.216...54S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2009.05.005.

- National Geophysical Data Center (1972). "Comments for the Significant Earthquake". National Centers for Environmental Information. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information. doi:10.7289/V5TD9V7K. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, "Res Gestae", 26.10.15–19

- Today in Earthquake History Archived 2007-03-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Stiros 2001, p. 545

- Stiros 2001, p. 546, fig. 1

- Stiros 2001, pp. 558–560, app. B

- Moreno, M. E., Los estudios de sismicidad histórica en Andalucía: Los terremotos históricos de la Provincia de Almería (PDF), Instituto Andaluz de Geofísica y Prevención de Desastres Sísmicos, pp. 124–126

- For summaries of the sources, see: Stiros 2001, pp. 557f., app. A

- Jeff Hecht (15 March 2008). "Mediterranean's 'horror' tsunami may strike again". New Scientist. 197 (2647): 16. doi:10.1016/S0262-4079(08)60641-7.

- Shaw, B.; Ambraseys, N.N.; England, P.C.; Floyd, M.A.; Gorman, G.J.; Higham, T.F.G.; Jackson, J.A.; Nocquet, J.-M.; Pain, C.C.; Piggott, M.D. (2008). "Eastern Mediterranean tectonics and tsunami hazard inferred from the AD 365 earthquake" (PDF). Nature Geoscience. 1 (4): 268–276. Bibcode:2008NatGe...1..268S. doi:10.1038/ngeo151. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2011.

- Polonia, Alina; Bonatti, Enrico; Camerlenghi, Angelo; Lucchi, Renata Giulia; Panieri, Giuliana; Gasperini, Luca (December 2013). "Mediterranean megaturbidite triggered by the AD 365 Crete earthquake and tsunami". Scientific Reports. 3 (1): 1285. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E1285P. doi:10.1038/srep01285. PMC 3573340. PMID 23412517.

- Stiros 2001, pp. 545f.

- Kelly 2004, p. 145

- Stiros 2001, pp. 547 & 557f.

- Stiros 2001, p. 553

- Soren, D. (1988). "The Day the World Ended at Kourion. Reconstructing an Ancient Earthquake". National Geographic. 174 (1): 30–53.

- Kelly 2004, p. 141

- Stiros 2001, pp. 549, 557

References

- Kelly, Gavin (2004), "Ammianus and the Great Tsunami" (PDF), The Journal of Roman Studies, 94: 141–167, doi:10.2307/4135013, hdl:20.500.11820/635a4807-14c9-4044-9caa-8f8e3005cb24, JSTOR 4135013, S2CID 160152988

- Stiros, Stathis C. (2001), "The AD 365 Crete Earthquake and Possible Seismic Clustering During the Fourth to Sixth Centuries AD in the Eastern Mediterranean: A Review of Historical and Archaeological Data", Journal of Structural Geology, 23 (2–3): 545–562, Bibcode:2001JSG....23..545S, doi:10.1016/S0191-8141(00)00118-8

Further reading

Literary discussion on sources and providentialist tendencies

- G. J. Baudy, "Die Wiederkehr des Typhon. Katastrophen-Topoi in nachjulianischer Rhetorik und Annalistik: zu literarischen Reflexen des 21 Juli 365 n.C.", JAC 35 (1992), 47–82

- M. Henry, "Le temoignage de Libanius et les phenomenes sismiques de IVe siecle de notre ere. Essai d'interpretation', Phoenix 39 (1985), 36–61

- F. Jacques and B. Bousquet, “Le raz de maree du 21 juillet 365“, Mélanges de l'École française de Rome, Antiquité (MEFRA), Vol. 96, No.1 (1984), 423–61

- C. Lepelley, "Le presage du nouveau desastre de Cannes: la signification du raz de maree du 21 juillet 365 dans l'imaginaire d' Ammien Marcellin", Kokalos, 36–37 (1990–91) [1994], 359–74

- M. Mazza, "Cataclismi e calamità naturali: la documentazione letteraria", Kokalos 36–37 (1990–91) [1994], 307–30

Geological discussion

- Bibliography in: E. Guidoboni (with A. Comastri and G. Traina, trans. B. Phillips), Catalogue of Ancient Earthquakes in the Mediterranean Area up to the 10th Century (1994)

- D. Kelletat, "Geologische Belege katastrophaler Erdkrustenbewegungen 365 AD im Raum von Kreta", in E. Olhausen and H. Sonnabend (eds), Naturkatastrophen in der antiken Welt: Stuttgarter Kolloquium zur historischen Geographie des Altertums 6, 1996 (1998), 156–61

- P. Pirazzoli, J. Laborel, S. Stiros, "Earthquake clustering in the Eastern Mediterranean during historical times", Journal of Geophysical Research, Vol. 101 (1996), 6083–6097

- S. Price, T. Higham, L. Nixon, J. Moody, "Relative sea-level changes in Crete: reassessment of radiocarbon dates from Sphakia and West Crete", BSA 97 (2002), 171–200

- G. Waldherr, "Die Geburt der "kosmischen Katastrophe". Das seismische Großereignis am 21. Juli 365 n. Chr.", Orbis Terrarum 3 (1997), 169–201

- Stiros, Stathis C. (2020), "Was Alexandria (Egypt) Destroyed in A.D. 365? A Famous Historical Tsunami Revisited", Seismological Research Letters, 91 (5): 2662–2673, Bibcode:2020SeiRL..91.2662S, doi:10.1785/0220200045, S2CID 225284716

- Robertson, J.; Roberts, G.P.; Ganas, A.; Meschis, M.; Gheorghiu, D.M.; Shanks, R.P. (2023), "Quaternary uplift of palaeoshorelines in southwestern Crete: The combined effect of extensional and compressional faulting", Quaternary Science Reviews, 316: 108240, doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108240

- Causse, M.; Maufroy, E.; André, L.; Bard, P.-Y. (2023). "What Was the Level of Ground Motion across Europe during the Great A.D. 365 Crete Earthquake?". Seismological Research Letters. 94 (5): 2397–2410. doi:10.1785/0220220385. ISSN 0895-0695.

External links

- Ancient Mediterranean Tsunami May Strike Again – National Geographic

- The 365 A.D. Tsunami Destruction of Alexandria, Egypt: Erosion, Deformation of Strata and Introduction of Allochthonous Material Archived 2017-05-25 at the Wayback Machine – Geological Society of America

- Ammianus Marcellinus Online Project

- Ancient city by the sea rises amid Egypt's resorts – Associated Press

- The tsunami of 365 – Livius.org

- Earthquake and tsunami of July 21, 365 AD in the eastern Mediterranean Sea – George Pararas-Carayannis

.png.webp)