Carlyle's House

Carlyle's House, in Cheyne Row, Chelsea, central London, was the home of the Scottish essayist, historian and philosopher Thomas Carlyle and his wife Jane from 1834 until his death. The home of these writers was purchased by public subscription and placed in the care of the Carlyle's House Memorial Trust in 1895. They opened the house to the public and maintained it until 1936, when control of the property was assumed by the National Trust, inspired by co-founder Octavia Hill's earlier pledge of support for the house.[1] It became a Grade II listed building in 1954 and is open to the public as a historic house museum.

Photograph of Carlyle's House, 2015 | |

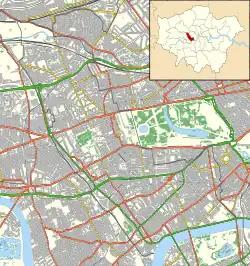

Location within Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea | |

| Location | Cheyne Row London, SW3 United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°29′3.48″N 0°10′12″W |

| Type | Historic house museum |

| Owner | National Trust |

| Public transit access | |

| Nearest parking | Limited metered street parking |

| Website | www |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Designated | 24 June 1954 |

| Reference no. | 1358142 |

| Building type | Georgian terraced house |

| Open: Yearly | March–October |

| Open: Weekly | Wednesday-Sunday and Bank Holiday Mondays |

The Carlyles in residence

In the early months of 1834, Carlyle had decided to move from Craigenputtock, the couple's residence in Dumfriesshire, Scotland, to London. He arrived in London in May, seeking his friend Leigh Hunt, whom he had asked to keep an eye out for a likely property. Carlyle, discovering that Hunt had done nothing of the kind, found a promising house himself, very close to the Hunt residence in Chelsea. The Carlyles moved into 5 Cheyne Row on 10 June 1834; the street address was changed to 24 in 1877. The house became central to Victorian intellectual life, a place of pilgrimage for literati, scientists, clergymen and political figures from all over Europe and North America. Carlyle did most of his writing there from The French Revolution onward.[1]

The building dates from 1708 and is a typical Georgian terraced house, a modestly comfortable home where the Carlyles lived with one servant and Jane's dog, Nero. It is preserved very much as it was when the Carlyles lived there, despite a later occupant with scores of cats and dogs. It is a good example of a middle-class Victorian home. Devotees tracked down many items of furniture owned by the Carlyles. It contains some of the Carlyles' books (many on permanent loan from the London Library, which was established by Carlyle). It also contains pictures, personal possessions, portraits by artists such as James Abbott McNeill Whistler and Helen Allingham, and memorabilia assembled by their admirers.

The house is made up of four floors. The kitchen is in the basement. The ground floor was the parlour. The first floor holds both the drawing room/library and Jane's bedroom. Thomas's bedroom was on the second floor and is now the custodian's residence. While researching in preparation for his History of Frederick the Great, Carlyle found the noise from the street and his neighbours intolerable, so in 1854 he had a "soundproof room" constructed in the top story.[2] The house has a small walled garden which is preserved much as it was when Thomas and Jane lived there; the fig tree still produces fruit.

The house may have been the model for the Hilberrys' house in Virginia Woolf's Night and Day (1919).[3]

Stanford and Thea Holme

The theatre producer Stanford Holme became curator of the house and moved there with his wife, the actress Thea Holme, in 1959.[4] She took up writing, beginning with a book about the lives of Thomas and Jane Carlyle at the house, The Carlyles at Home (1965).[4]

See also

Bibliography

- Adcock, A. St. John (1912). "Chelsea Memories". Famous Houses and Literary Shrines of London. London: J. M. Dent & Sons, Ltd.

- Blunt, Reginald (1895). The Carlyles' Chelsea Home, being some account of No. 5, Cheyne Row. York Street, Covent Garden, London: George Bell and Sons.

- Campbell, Ian (1991). "Carlyle House". Carlyle Annual (12): 65–90 – via JSTOR.

- Carlyle's House. London: The National Trust. 1992.

- Hardwick, Michael; Hardwick, Mollie (1970). "Carlyle's House, Chelsea". A Literary Journey: Visits to the Homes of Great Writers. South Brunswick, New York: A. S. Barnes and Company. pp. 6–10.

- Harland, Marion (1898). "No. 24 Cheyne Row". Where Ghosts Walk: The Haunts of Familiar Characters in History and Literature. New York: G. P. Putnam. pp. 63–81.

- Holme, Thea (1965). The Carlyles at Home. London: Oxford University Press.

- Hubbard, Elbert (1916). "Thomas Carlyle". Little Journeys To the Homes of the Great. New York: The Roycrofters.

- Illustrated Memorial Volume of the Carlyle's House Purchase Fund Committee: with Catalogue of Carlyle's Books, Manuscripts, Pictures and Furniture Exhibited Therein. London: The Carlyle's House Memorial Trust. 1896.

- Shelley, Henry C. (1895). "Carlyle in London". The Homes and Haunts of Thomas Carlyle. London: Westminster Gazette. pp. 87–140.

- Soseki, Natsume (2004). "The Carlyle Museum". The Tower of London. Translated by Flanagan, Damian. Peter Owen Publishers.

- Woolf, Virginia (1975). "Great Men's Houses". The London Scene. Hogarth Press.

- Woolf, Virginia (2003). "Carlyle's House". In Bradshaw, David (ed.). Carlyle's House and Other Sketches. London: Hesperus Press Limited. pp. 3–4.

References

- Cumming, Mark, ed. (2004). "Cheyne Row, Chelsea". The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Madison and Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 90–91. ISBN 978-1-61147-172-4.

- Bossche, Chris R. Vanden (2004). "Frederick the Great: Composition and Publication". In Cumming, Mark (ed.). The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Madison and Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-61147-172-4.

- "relationship". mural.uv.es. Retrieved 15 June 2022.

- "Thea Holme". The Times. 9 December 1980. p. 15. Retrieved 29 August 2014. (subscription required)

External links

Media related to Carlyle's House at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Carlyle's House at Wikimedia Commons- Official website