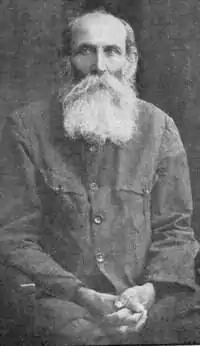

A. D. Gordon

Aaron David Gordon (Hebrew: אהרן דוד גורדון; 9 June 1856 – 22 February 1922), more commonly known as A. D. Gordon, was a Labour Zionist thinker and the spiritual force behind practical Zionism and Labor Zionism. He founded Hapoel Hatzair, a movement that set the tone for the Zionist movement for many years to come. Influenced by Leo Tolstoy and others, it is said that in effect he made a religion of labor. Gordon moved to Ottoman Palestine in 1904, at age 48, where he was revered by younger Zionist pioneers for leading by example.

Aaron David Gordon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | June 9, 1856 |

| Died | February 22, 1922 (aged 65) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western Philosophy |

| School | Existential philosophy, Labor Zionism |

Main interests | Ethics, epistemology, Jewish philosophy |

Notable ideas | Direct Experience (Hebrew: חוויה, Chavaya) vs Consciousness |

Biography

Aaron David Gordon was the only child of a well-to-do family of Orthodox Jews.[1] He was self-educated in both religious and general studies, and spoke several languages.[2] For thirty years, he managed an estate, where he proved to be a charismatic educator and community activist. Gordon married his cousin, Faige Tartakov, at a young age and had seven children with her, though only two of them survived.

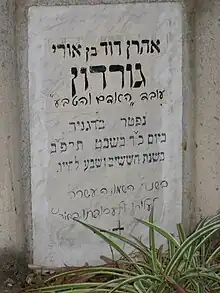

Gordon died of throat cancer on Kibbutz Degania Alef in 1922 at the age of 66.

Zionist activism

Gordon was an early member of the Hibbat Zion movement and made aliyah to Ottoman Palestine in 1904, when he was 48, after being persuaded by his wife not to emigrate to America. His daughter Yael followed him in 1908 and his wife about a year later, but his son stayed behind to continue his religious studies – he seems to have refused to accompany his father because of differences in their religious outlooks. Four months after she arrived in the country, his wife became ill and died. Gordon lived in Petah Tikva and Rishon LeZion, moved to the Galilee in 1912, travelled the country taking manual jobs and engaging the youth, until finally settling in Kvutzat Degania near the Sea of Galilee in 1919.[3] He lived simply and supported himself as a hired agricultural hand, while writing his emerging philosophy at night. Although he participated in the Zionist Congress of 1911, Gordon refused to become involved in any of the Zionist political parties, out of principle.

In 1905 he founded and led Hapoel Hatzair ("The Young Worker"), a non-Marxist, Zionist movement, as opposed to the Poale Zion movement which was more Marxist in orientation and associated with Ber Borochov and Nahum Syrkin.

Views and opinions

Gordon believed that all of Jewish suffering could be traced to the parasitic state of Jews in the Diaspora, who were unable to participate in creative labor. To remedy this, he sought to promote physical labor and agriculture as a means of uplifting Jews spiritually. It was the experience of labor, he believed, that linked the individual to the hidden aspects of nature and being, which, in turn were the source of vision, poetry, and the spiritual life. Furthermore, he also believed that working the land was a sacred task, not only for the individual but for the entire Jewish people. Agriculture would unite the people with the land and justify its continued existence there. In his own words: "The Land of Israel is acquired through labor, not through fire and not through blood." Return to the soil would transform the Jewish people and allow its rejuvenation, according to his philosophy. A.D. Gordon elaborated on these themes, writing:

The Jewish people has been completely cut off from nature and imprisoned within city walls for two thousand years. We have been accustomed to every form of life, except a life of labor- of labor done at our behalf and for its own sake. It will require the greatest effort of will for such a people to become normal again. We lack the principal ingredient for national life. We lack the habit of labor… for it is labor which binds a people to its soil and to its national culture, which in its turn is an outgrowth of the people's toil and the people's labor. ... We, the Jews, were the first in history to say: "For all the nations shall go each in the name of its God" and "Nations shall not lift up sword against nation" - and then we proceed to cease being a nation ourselves.

As we now come to re-establish our path among the ways of living nations of the earth, we must make sure that we find the right path. We must create a new people, a human people whose attitude toward other peoples is informed with the sense of human brotherhood and whose attitude toward nature and all within it is inspired by noble urges of life-loving creativity. All the forces of our history, all the pain that has accumulated in our national soul, seem to impel us in that direction... we are engaged in a creative endeavor the like of which is itself not to be found in the whole history of mankind: the rebirth and rehabilitation of a people that has been uprooted and scattered to the winds... (A.D. Gordon, "Our Tasks Ahead" 1920)

Gordon perceived nature as an organic unity. He preferred organic bonds in society, like those of family, community and nation, over "mechanical" bonds, like those of state, party and class. Jews were cut off from their nation, living in Diaspora, they were cut off from direct contact with nature; they were cut off from the experience of sanctity, and the existential bond with the infinite. Gordon wrote:

[W]e are a parasitic people. We have no roots in the soil, there is no ground beneath our feet. And we are parasites not only in an economic sense, but in spirit, in thought, in poetry, in literature, and in our virtues, our ideals, our higher human aspirations. Every alien movement sweeps us along, every wind in the world carries us. We in ourselves are almost non-existent, so of course we are nothing in the eyes of other people either[4]

More than just a theoretician, he insisted on putting this philosophy into practice, and refused to take any clerical position that was offered to him. He was an elderly intellectual of no great physical strength and with no experience doing manual labor, but he took up the hoe and worked in the fields, always focusing on the aesthetics of his work. He served as a model of the pioneering spirit, descending to the people and remaining with them no matter what the consequences were. He experienced the problems faced by the working class, suffering from malaria, poverty, and unemployment. But he did have admirers and followers who turned to him for advice and help.

Gordon had always been a principled individual—even as a young man he refused to allow his parents to pay the customary bribe so that he would be exempted from military service, arguing that if he did not serve, someone else would have to serve instead of him. In the end, he spent six months in the army, but was released when it was discovered that he was not in good enough physical shape. He later refused to accept payment for his articles or the classes he taught, citing the Mishnah that states "Do not turn the Torah into a source of income." At the same time, he did not lapse into dogmatism either. When Rachel Bluwstein (1890–1931), known as 'Rachel the Poetess', asked his opinion about whether she should go overseas to study, an idea that was anathema to most of the Zionist leadership, he encouraged her to do so. Gordon's moods alternated between enormous frustration and great hope for the future. He believed that an idealistic new generation of creative Jews would emerge in the Land of Israel, with a high sense of morals, a deep spiritual commitment, and a commitment to their fellow human beings. Toward the end of his life, however, he preferred to isolate himself in nature. From a letter he wrote to Rachel the Poetess, it seems that he grew more and more frustrated with people's petty squabbles and selfish interests.

Although formerly an Orthodox Jew, Gordon rejected religion later in his life. Students of his writings have found that Gordon was greatly influenced by Russian author Leo Tolstoy, as well as by the Hassidic movement and Kabbalah. Many have also found parallels between his ideas and those of his contemporary, Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the spiritual father of Religious Zionism.

Central to Gordon's philosophy is the idea that the cosmos is a unity. This notion in which man and nature are one and all men are organic parts of the cosmos is reflected throughout his thought, including political issues, the role of women in the modern world, and Jewish attitude to the Arabs.[5] He believed the central test for the reborn Jewish nation would be the attitude of the Jews to the Arabs. The Biblical principle regarding "the stranger that sojourns in thy midst" guided his thought on this matter. In his statutes for labor settlements, which he drew up in 1922, Gordon included a clause that said that land should be assigned to Arabs wherever new settlements were founded, to ensure their welfare. He believed that this principle of good neighborliness should be undertaken for moral reasons rather than tactical advantage, and that it would eventually lead to a spirit of universal human solidarity.[6] A summary of his thinking on Jewish-Arab relations can be found in his work Mibachutz, where he wrote:

"Our relations to the Arabs must rest on cosmic foundations. Our attitude toward them must be one of humanity, of moral courage which remains on the highest plane, even if the behavior of the other side is not all that is desired. Indeed their hostility is all the more a reason for our humanity."[7]

Legacy and commemoration

Gordonia, a Zionist youth movement, created in Poland in 1925 in order to put Gordon's teachings into practice, established several kibbutzim in Israel.

Published works (English)

- Selected Essays by Aaron David Gordon (tr.: Frances Burnce), New York: League for Labor Palestine, 1938, ISBN 0405052669 (0-405-05266-9) Reprint: Selected Essays by Aaron David Gordon, New York: Arno Press, 1973, ISBN 0405052669 (0-405-05266-9)

References

- "zionism/hapoel-hatzair/gordon".

- Aaron David Gordon Biography.

- Aharon David Gordon on the website of Kibbutz Degania Alef

- Sternhell, p. 48

- Bergman, Samuel Hugo. Faith and Reason: An Introduction to Modern Jewish Thought. B'nai B'rith Hillel Foundations, Inc., 1961, p.103.

- Bergman 1961. pps.115-116

- Mibachutz in Gordon's Collected Works, 1952, I, p.478. in Bergman 1961. p.116

External links

- Labor and Socialist Zionism at MidEastWeb for Coexistence

- Zionism and Israel Information Center Biography Section

- Myjewishlearning.com

- Haaretz.com, "Far From Reality" Review of New Life: Religion, Motherhood and Supreme Love in the Work of A.D. Gordon,