Eber-Nari

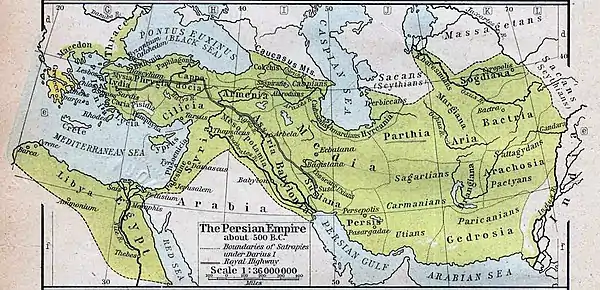

Eber-Nari (Akkadian, also Ebir-Nari), Abar-Nahara עבר-נהרה (Aramaic) or 'Ābēr Nahrā (Syriac) meaning "Beyond the River" or "Across the River" in both the Akkadian and Imperial Aramaic languages of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, i.e., the Western bank of the Euphrates from a Mesopotamian and Persian viewpoint), also referred to as Transeuphratia (French: Transeuphratène) by modern scholars, was a region of Western Asia and a satrapy of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC), Neo-Babylonian Empire (612–539 BC) and Achaemenid Empire (539–332 BC).

| Eber-Nari | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province of Achaemenid Empire | |||||||||

| 539 BCE–332 BCE | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| Historical era | Achaemenid era | ||||||||

• Conquest of Chaldea | 539 BCE | ||||||||

| 332 BCE | |||||||||

| |||||||||

In the trilingual Achaemenid royal inscription "DSf", the Akkadian Eber-Nari is referred to as Athura or Athuriya in Old Persian, and Aššur in the Elamite.[1][2] The Targum Onkelos lists Nineveh, Calah, Reheboth, and Resen as being in the jurisdiction of Athura.

Name

- Akkadian: 𒆳𒂊𒄵𒀀𒇉, romanized: Eber-Nāri [KUR.e.bir.ID₂], lit. 'trans river' — i.e. the region west of the Euphrates.[3][4]

- Old Aramaic: עבר נהרה, romanized: ʿAvar Naharā, lit. 'trans river' — i.e. the other side of the Euphrates.[5][6]

- Hebrew: עבר הנהר, romanized: ʿĒḇer haNāhār, lit. 'the trans river' — i.e. beyond the river.[5][7][8][9]

The province is also mentioned extensively in the Biblical books of Ezra and Nehemiah as עבר הנהר ('Ever Hannahar' in modern pronunciation). Additionally, sharing the same root meaning, Eber (pronounced Evver) was also a character in the Hebrew Bible from which the term Hebrew was widely believed to have been derived (see: Eber), thus the Hebrews were inferred to have been the people who crossed into Canaan across the (Euphrates or the Jordan) river.

History

.jpg.webp)

The term was established during the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–605 BC) in reference to its Levantine colonies, and the toponym appears in an inscription of the 7th century BC Assyrian king Esarhaddon. The region remained an integral part of the Assyrian empire until its fall in 612 BC, with some northern regions remaining in the hands of the remnants of the Assyrian army and administration until at least 605 BC, and possibly as late as 599 BC.[10]

Subsequent to this Eber-Nari was fought over by the Neo-Babylonian Empire (612–539 BC) and Egypt, the latter of which had entered the region in a belated attempt to aid its former Assyrian overlords. The Babylonians and their allies eventually defeated the Egyptians (and remnants of the Assyrian army) and assumed control of the region, which they continued to call Eber-Nari.

The Babylonians were overthrown by the Persian Achaemenid Empire (539–332 BC), and the Persians assumed control of the region. Having themselves spent centuries under Assyrian rule, the Achaemenid Persians retained the Imperial Aramaic and Imperial organisational structures of their Assyrian predecessors.

In 535 BC the Persian king Cyrus the Great organized some of the newly conquered territories of the former Neo-Babylonian Empire as a single satrapy; "Babylonia and Eber-Nari", encompassing southern Mesopotamia and the bulk of the Levant. Northern Mesopotamia, the north east of modern Syria and south east Anatolia remaining as Athura (Assyria) (Achaemenid Assyria).[11]

The satrap of Eber-Nari resided in Babylon and there were subgovernors in Eber-Nari, one of which was Tattenai, mentioned in both the Bible and Babylonian cuneiform documents.[12] This organization remained untouched until at least 486 BC (Xerxes I's reign), but before c. 450 BC the "mega-satrapy" was split into two—Babylonia and Eber-Nari.[13]

Herodotus' description of the Achaemenid tax district number V fits with Eber-Nari. It comprised Aramea, Phoenicia, and Cyprus (which was also included in the satrapy[14]). Herodotus did not include in the tax list the Arabian tribes of the Arabian peninsula, identified with the Qedarites,[15] that did not pay taxes but contributed with a tax-like gift of frankincense.

Eber-Nari was dissolved during the Greek Seleucid Empire (312–150 BC), the Greeks incorporating both this region and Assyria in Upper Mesopotamia into Seleucid Syria during the 3rd century BC. Syria was originally a 9th-century Indo-Anatolian derivation of Assyria and was used for centuries only in specific reference to Assyria and the Assyrians (see Name of Syria), a land which in modern terms actually encompassed only the northern half of Iraq, north east Syria and south east Turkey and not the bulk of Greco-Roman, Byzantine or modern nation of Syria. However, from this point the terms Syrian and Syriac were used generically and often without distinction to describe both Assyria proper and Eber-Nari/Aram, and their respective Assyrian and Aramean/Phoenician populations.

Notes

- John, Boardman (1991). The Cambridge Ancient History: pt. 1. The prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. Cambridge University Press. pp. 433–434.

In the Babylonian version of the text the transportation to Babylon is credited to the people of eber nari, showing that to the scribe or scribes of these inscriptions the Babylonian equivalent of Old Persian Athura was eber nari...

- Shawn Tuell, Steven. The Law of the Temple in Ezekiel 40-48. Scholars Press. p. 158.

Moreover, in a bilingual building inscription of Darius at Susa, the Old Persian kara hya Athuriya ("people of the Assyrians") is rendered in Akkadian as sabe sa eber nari ("people of eber nari")...

- Miller, Douglas B.; Shipp, R. Mark (1996). An Akkadian Handbook: Paradigms, Helps, Glossary, Logograms, and Sign List. Eisenbrauns. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-931464-86-7.

Eber nāri (geo) the region west of the Euphrates, Syria—NA, NB, LB.

- "saao/saa01/qpn-x-places/Eber-nari[across the river]". oracc.museum.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2021-03-21.

- Lester L. Grabbe (27 July 2006). A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period (vol. 1): The Persian Period (539-331BCE). Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-567-21617-5.

The region of Ebir-nari (Transeuphrates, called Avarnaharā' in Aramaic and Ēver-ha-Nāhār in Hebrew)

- Thomas Kelly Cheyne; John Sutherland Black (1903). Encyclopædia biblica: a critical dictionary of the literary, political and religious history, the archæology, geography, and natural history of the Bible. A. and C. Black. p. 4857.

Image of p. 4857 at Google Books

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - George V. Wigram (1890). The Englishman's Hebrew and Chaldee Concordance of the Old Testament: Being an Attempt at a Verbal Connection Between the Original and the English Translation: With Indexes, a List of the Proper Names, and Their Occurrences, Etc. Samuel Bagster and sons. pp. 798–799.

Image of p. 798 at Google Books

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - Wilhelm Gesenius; Francis Brown; Samuel Rolles Driver (1906). A Hebrew and English Lexicon of the Old Testament: With an Appendix Containing the Biblical Aramaic. Houghton, Mifflin. p. 719.

Image of p. 719 at Google Books

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - David Noel Freedman; Allen C. Myers; Astrid B. Beck (2000). "Beyond the River". Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. W.B. Eerdmans. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-8028-2400-4.

- Tuell 1991, p. 51.

- Dandamaev 1994.

- Olmstead 1944.

- Stolper 1989; Dandamaev 1994.

- Dandamaev 1994

- Dumbrell 1971; Tuell 1991.

References

- Dandamaev, M (1994): "Eber-Nari", in E. Yarshater (ed.) Encyclopaedia Iranica vol. 7.

- Drumbrell, WJ (1971): "The Tell el-Maskuta Bowls and the 'Kingdom' of Qedar in the Persian Period", BASOR 203, pp. 33–44.

- Elayi, J; Sapin, J (1998): "Beyond the River: New Perspectives on Transeuphratene". A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-85075-678-1.

- Olmstead, AT (1944): "Tettenai, Governor of Across the River", JNES 3 n. 1, p. 46.

- Stolper, MW (1989): "The Governor of Babylon and Across-the-River in 486 B.C.", JNES 48 n. 4, pp. 283–305.

- Tuell (1991): "The Southern and Eastern Borders of Abar-Nahara", BASOR n. 284, pp. 51–57.

- Parpola, S (1970): "Neo-Assyrian Toponyms, Alter Orient und Altes Testament". Veröffentlichungen zur Kultur und Geschichte des Alten Orients und des Alten Testaments 6, Neukirchen-Vluyn, p116

- Zadok, R (1985): "Geographical Names According to New and Late-Babylonian Texts", Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, Répertoire Géographique des Textes Cunéiformes 8, Wiesbaden, p129

._Circa_353-333_BC.jpg.webp)