Abbas ibn Abi al-Futuh

Abu’l-Faḍl ʿAbbās ibn Abī al-Futūḥ al-Ṣinhājī (Arabic: ابوالفضل عباس ﺑﻦ ﺍﺑﻲ ﺍﻟﻔﺘﻮﺡ الصنهاجي), also known by the honorific al-Afḍal Rukn al-Dīn (lit. 'Most Excellent Pillar of the Faith'),[1] was a prince of the Zirid dynasty of Ifriqiya who served as vizier of the Fatimid Caliphate in 1153–1154.

Abbas ibn Abi al-Futuh | |

|---|---|

| Born | before 1115 |

| Died | 7 June 1154 near Eilat |

| Nationality | Fatimid Caliphate |

| Occupation(s) | Military commander, governor of Cairo, vizier |

| Years active | before 1149 – 1154 |

Abbas' family fled to Egypt when he was an infant. He grew up in the household of the Fatimid general and governor al-Adil ibn al-Sallar, whom his mother married after Abbas' father died. Abbas aided his step-father in the latter's revolt and assumption of the vizierate in 1149, pursuing and killing his predecessor, Ibn Masal. In 1153, charged with relieving the Siege of Ascalon by the Crusaders of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, he instead arranged the murder of Ibn al-Sallar and became vizier himself. Along with his son, Nasr, Abbas was then responsible for the murder of Caliph al-Zafir in April 1154, and the accession of the infant al-Fa'iz to the throne. This provoked the women of the Fatimid harem to call upon the governor Tala'i ibn Ruzzik for aid. Ibn Ruzzik overthrew Abbas, who with a few followers fled to Syria. The party was intercepted by the Crusaders, and Abbas was killed on 7 June 1154. Nasr was handed over to the Fatimids, who had him executed.

Life

Abbas was born shortly before 1115, to Abu al-Futuh, a prince of the Zirid dynasty.[1] The Zirids had ruled Ifriqiya since 973 on behalf of the Fatimid Caliphate, after the latter had moved its seat to Egypt.[2] Abbas' great-grandfather, al-Mu'izz ibn Badis, however, had rejected Fatimid suzerainty in 1048/49 and turned to the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate instead.[3]

In 1115, when Abbas was still an infant, his father was banished to Alexandria along with his family by his brother, the Zirid emir Ali ibn Yahya (r. 1016–1021).[1][4] There they were warmly welcomed by the Fatimid authorities, on the express orders of Caliph al-Amir (r. 1101–1130).[4] When Abu al-Futuh died, Abbas' mother, Bullara, married a second time, to the powerful Fatimid general and governor of Alexandria, al-Adil ibn al-Sallar.[1][4]

Under Ibn al-Sallar

In 1149, the new caliph, the 16-year-old al-Zafir (r. 1149–1154), appointed his father's long-standing chief secretary, Ibn Masal, to the vacant vizierate.[5] This appointment was opposed by Ibn al-Sallar, who marched on Cairo and forced al-Zafir to appoint him as vizier instead.[1][4] Abbas likely accompanied his stepfather during his uprising, and was then tasked with the pursuit of Ibn Masal, who had fled the capital to rally troops in Lower Egypt.[1][4]

Ibn Masal managed to gather an army of Lawata Berbers, Bedouin Arabs, native Egyptians, and Black African troops, and prevailed in first engagement with Abbas.[4][6] Abbas received reinforcements from Cairo, led by Usama ibn Munqidh, and when Ibn Masal made for Upper Egypt, he was overtaken and decisively defeated at Dalas, near Bahnasa, on 19 February 1150. Abbas returned to Cairo, bringing Ibn Masal's severed head with him.[4][6] Thus rid of his rival, Ibn al-Sallar made a triumphal entry into Cairo on 24 March.[1] Few details are known about Abbas' life during the next four years of his stepfather's vizierate; according to Ibn al-Dawadari and Ibn Taghribirdi, Abbas may have served as governor of one half of Cairo during this time (although the two authors differ on which half, eastern or western).[4] It is also during this time that Abbas's son, Nasir al-Din Nasr, became a favourite of Caliph al-Zafir.[1]

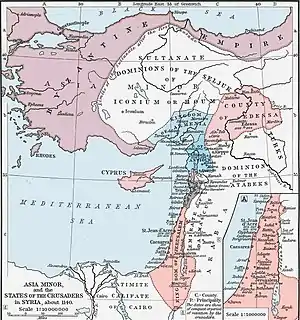

Abbas reappears in the sources in early 1153, when he was appointed to lead an expedition to Ascalon, at the time the last remaining stronghold that the Fatimids held in the Levant against the Crusader states.[1][4] Since January 1153, the city had been under siege by the Crusaders under King Baldwin III of Jerusalem.[7] The expedition set out, but at Bilbays Abbas halted and decided to instead overthrow his stepfather and usurp the vizierate. Most medieval historians, apparently drawing from the same account, report that Usama ibn Munqidh, a friend to both Abbas and Ibn al-Sallar, was involved. Abbas and Usama are said to have been discussing the pleasures of Egypt, and their reluctance to abandon them. At the instigation of Usama, Abbas resolved to secretly send his son, Nasr, who had the ear of the caliph, to Cairo in order to ask al-Zafir to depose Ibn al-Sallar. This was easily achieved, as Ibn al-Sallar's rule was regarded as oppressive, and the caliph apparently had already sought to get rid of his over-mighty vizier. Ibn al-Sallar was killed in his sleep by Nasr on 3 April 1153, and Abbas quickly returned to Cairo and was named as vizier.[1][4][7] Abandoned to its fate, Ascalon surrendered to the Crusaders on 20 August 1153.[1][7]

Vizierate and downfall

Abbas' tenure as vizier was troubled from the outset.[4] Ibn al-Sallar's supporters threatened to kill Usama for his rumoured role in the vizier's downfall,[4] while Abbas and Nasr, according to Usama's memoirs, were now suspicious of each other, so that Usama had to mediate between them.[1] A major issue was Nasr's close, and widely suspected to be sexual, relationship with the caliph, which aroused negative reactions among the court, while Usama also claims that al-Zafir incited Nasr to kill his own father.[4] The veracity of Usama's claims is impossible to verify, but his version has been taken up by most medieval sources. There are a few diverging accounts, such as Ibn Taghrirbirdi, who rejects any sexual relationship between Nasr and the caliph, but claims that Nasr plotted to murder and replace his father on his own account.[4]

In the end, Abbas and Nasr, urged by Usama, turned on al-Zafir: on the night of 16 April 1154, Nasr invited the caliph to the vizieral palace of Dar Yunis, and murdered him.[1][4] Abbas then accused two of al-Zafir's brothers, Jibra'il and Yusuf, of the murder, and had them executed.[4][8] The only son of al-Zafir, the four-year-old Isa, was raised to the caliphate with the regnal name al-Fa'iz.[1][9][8]

The court and populace now had enough of the incessant plotting, culminating in the murder of a caliph.[4] The terrified women of the Fatimid harem called upon the Armenian-born governor of Asyut, Tala'i ibn Ruzzik, for assistance, reportedly sending their own cut hair in supplication.[8][10] Ibn Ruzzik readily agreed and marched on Cairo. Abbas tried to resist, but faced general opposition: most of the troops were reluctant to support him or defected outright, and the remainder found themselves under attack by the populace with stones. In the end, on 29 May Abbas had to force his way out of the capital with his son and a handful of followers.[8][11]

The party made for the Levant, but was intercepted on 7 June by the Crusaders near Eilat; reportedly al-Zafir's sister had informed the Crusaders of their whereabouts and offered a reward for Abbas' death. In the ensuing battle, Usama escaped, Abbas was killed, and Nasr was captured was sold to the Fatimids.[1][4][12] Nasr was mutilated and beaten to death by the palace women in June/July 1155. His corpse was then publicly displayed at the Bab Zuwayla gate.[4][12]

References

- Becker & Stern 1960, p. 9.

- Brett 2017, pp. 85, 112ff..

- Brett 2017, p. 184.

- Sajjadi 2015.

- Halm 2014, p. 223.

- Canard 1971, p. 868.

- Brett 2017, p. 282.

- Brett 2017, p. 283.

- Halm 2014, p. 237.

- Halm 2014, p. 238.

- Halm 2014, pp. 238–239.

- Halm 2014, p. 240.

Sources

- Becker, C. H. & Stern, S. M. (1960). "ʿAbbās b. Abī al-Futūḥ". In Gibb, H. A. R.; Kramers, J. H.; Lévi-Provençal, E.; Schacht, J.; Lewis, B. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume I: A–B (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 9. OCLC 495469456.

- Brett, Michael (2017). The Fatimid Empire. The Edinburgh History of the Islamic Empires. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-4076-8.

- Canard, Marius (1971). "Ibn Maṣāl". In Lewis, B.; Ménage, V. L.; Pellat, Ch. & Schacht, J. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume III: H–Iram (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. p. 868. OCLC 495469525.

- Halm, Heinz (2014). Kalifen und Assassinen: Ägypten und der vordere Orient zur Zeit der ersten Kreuzzüge, 1074–1171 [Caliphs and Assassins: Egypt and the Near East at the Time of the First Crusades, 1074–1171] (in German). Munich: C. H. Beck. doi:10.17104/9783406661648-1. ISBN 978-3-406-66163-1.

- Sajjadi, Sadeq (2015). "ʿAbbās b. Abī al-Futūḥ". In Madelung, Wilferd; Daftary, Farhad (eds.). Encyclopaedia Islamica Online. Translated by Hassan Lahouti. Brill Online. doi:10.1163/1875-9831_isla_SIM_0012. ISSN 1875-9831.