Chinese Taipei

"Chinese Taipei" is the term used in various international organizations and tournaments for groups or delegations representing the Republic of China (ROC), a country commonly known as Taiwan.

| Chinese Taipei | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 中華臺北 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 中华台北 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Postal | Chunghwa Taipei | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 臺澎金馬個別關稅領域 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 台澎金马个别关税领域 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|---|

|

|

Due to the One-China principle stipulated by the People's Republic of China (PRC, China), Taiwan, being a non-UN member after its expulsion in 1971 with ongoing dispute of its sovereignty, was prohibited from using or displaying any of its national symbols such as national name, anthem and flag that would represent the statehood of Taiwan at international events.[1] This dissension eventually came to a compromise when the term "Chinese Taipei" was first proposed in the Nagoya Resolution in 1979, whereby the ROC/Taiwan and the PRC/China recognize the right of participation to each other and remain as separate teams in any activities of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and its correlates. This term came into official use in 1981 following a name change of the Republic of China Olympic Committee (ROCOC) to Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee. Such arrangement later became a model for the ROC/Taiwan to continue participating in various international organizations and affairs in diplomacy other than the Olympic Games, including the World Trade Organization, the World Health Organization, the Metre Convention, APEC, and international pageants.

"Chinese Taipei" is a deliberately ambiguous term, which is equivocal about the political status of the ROC/Taiwan, and the meaning of "Chinese" (Zhōnghuá, Chinese: 中華) is also ambiguous which can either be interpreted as national identity or cultural sphere (similar ethnonyms as Anglo, Arab, Hispanic or Iranian) by each party,[2][3] "Taipei" is only reflected as its capital city which does not specify the territorial extent of the ROC.[4] Since the IOC has ruled out the use of the name "Republic of China", the neologism was considered as an expedient resolution and a more inclusive term than just "Taiwan" to either the Kuomintang, the ruling party of the ROC at the time during the Nagoya Resolution, or the PRC, whilst both sides were contending their legitimacy over the whole "China" that regarded to encompass both of mainland China and Taiwan. To the PRC's perspective, whose persistent policy is to keep Taipei isolated on the world stage and balks at any use of "Taiwan" as official title, lest it lend Taiwan a sense of international recognition for its "independent statehood" that may present it as a separate entity from the PRC.[1][2][5][6] The term "Taiwan, China" or "Taipei, China" was rejected by the ROC government because it would simply be construed as Taiwan being a subordinate region to the PRC.[7][8]

The popular opinions in Taiwan have changed drastically in regard to the cross-strait relations and the nationalistic discourses since the democratization of Taiwan and the end of one-party rule by the Kuomintang,[3][9][10] "Chinese Taipei" has constantly been viewed as anachronistic, aggravating, or even a humiliating and shameful symbol by many Taiwanese.[2][6][9][11][12] An ongoing movement, the Taiwan Name Rectification Campaign seeks alteration of the formal name from "Chinese Taipei" to "Taiwan" for the representation in Olympic Games or further potential international events. A nationwide referendum was held in 2018, in which a proposal of the name change was rejected. The main argument voting against such a move was concerning that the consequence of the renaming impact is immensely uncertain, at worst, the renaming dispute could be used by China as an excuse to exclude Taiwan from participating in the Olympic Games completely and force its existing membership to be revoked.[13][12][10] This was the case when Taiwan was stripped of the right to host 2019 East Asian Youth Games amid its renaming issue with China during that year.[13][14][15]

Origins

Two Chinas at the Olympics

In the aftermath of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, the People's Republic of China (PRC) was established and the nationalist Republic of China (ROC) government retreated to Taiwan, previously a Qing territory that was ceded to Japanese rule from 1895 until its surrender at the end of World War II in 1945.[16][17] As time went on, the increased official recognition of the PRC in international activities, such as when accorded recognition in 1971 by the United Nations, instead of that accorded previously to the ROC saw existing diplomatic relations transfer from Taipei to Beijing.[18] The ROC needed to come to a beneficial conclusion to how it would be referred when there was participation by the PRC in the same forum.[19]

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) recognized both the PRC and the ROC Olympic Committees in 1954.[20] In 1958, The PRC withdrew its membership from the IOC and nine other international sports organizations in protest against the two-Chinas policy. After the withdrawal of the PRC, the IOC had been using a number of names in international Olympic activities to differentiate the ROC from the PRC. "Formosa" was used at the 1960 Summer Olympics, and "Taiwan" was used in 1964 and 1968.[21][22] In 1975, the PRC applied to rejoin the IOC as the sole sports organization representing the whole China.[20] The Taiwanese team, competing under the name of Republic of China at the previous Olympics, was refused to represent itself as the "Republic of China" or use "China" in its name by host Canadian government at the 1976 Summer Olympics.[23][24] The IOC then voted to change the name of the ROC team to "Taiwan", which was rejected by the ROC, and the ROC announced withdrawal from the 1976 Summer Olympics a day before the opening ceremony.[25]

The top ROC leadership at the time asserted Chinese nationalism, contending both parts of divided China are Chinese territories and Taiwan did not represent all the regions of the ROC.[26][4][27] What people refer to as Taiwan is one of several areas or islands (Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu in addition to Taiwan) and Taiwan alone did not reflect the "territorial extent" of the ROC. Furthermore, although it is true that most products from the area controlled by the ROC are labeled "made in Taiwan", the trade practices of the ROC are such that the regional area of production is used for labeling. Some wines from Kinmen are labeled "made in Kinmen", just as some perfume are labeled "made in Paris" and not "made in France". Therefore, the ROC government refused to accept the name of Taiwan during the period.

1979 IOC resolutions

In April 1979, the IOC recognized the Olympic Committee of the PRC and maintained recognition of the Olympic Committee located in Taipei at the 81st IOC Session held in Montevideo.[28][29] The resolution left problems relating to the names, anthems and flags of both committees unsolved. The PRC showed a willingness to allow Taiwan to be included in the IOC but objected to the resolution, reaffirming sports organizations in Taiwan must not use any of the emblems of the Republic of China.[20] He Zhenliang, a representative of the PRC, stated in Montevideo:

According to the Olympic Charter, only one Chinese Olympic Committee should be recognized. In consideration of the athletes in Taiwan having an opportunity to compete in the Olympic Games, the sports constitution in Taiwan could function as a local organization of China and still remain in the Olympic Movement in the name of the Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee. However, its anthem, flag and constitutions should be changed correspondingly.[30]

After the 81st Session, the IOC Executive Board designated the Olympic Committee in Beijing as the Chinese Olympic Committee, with the PRC's anthem, flag and emblem.[30][31] The Olympic Committee in Taipei was designated as the Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee, with a different anthem, flag and emblem from those the ROC used and which must be approved by the executive board. Lord Killanin, the president of the IOC, submitted the resolution to IOC members for a postal vote following the conclusion of the IOC Executive Board meeting held in October 1979 in Nagoya.[32][33] The resolution, known as the Nagoya Resolution, was approved in November 1979 by the IOC members, and later other international sports federations adopted the resolution.

The Nagoya Resolution was welcomed by the PRC as the resolution followed the PRC's One China principle,[20] whereas the ROC decided that the ROC Olympic Committee must strongly protest against the decisions.[27] From November 1979, the ROC Olympic Committee and Taiwan's IOC member, Henry Hsu, filed a series of lawsuits in Lausanne against the IOC for annulment of the Nagoya Resolution. Taiwanese officials also boycotted the 1980 Winter and Summer Games in protest of not being allowed to use the ROC's official name, flag and national anthem.[34][35]

1981 agreement

In 1980, the IOC amended the Olympic Charter so that all National Olympic Committees (NOCs) when participating in the Games could use delegation flags and anthems, instead of national ones.[27][36] Juan Antonio Samaranch, the new president of the IOC, met Henry Hsu several times to discuss the ROC Olympic Committee's status in the IOC. In order for the youth to participate in the Olympic Games and counteract the PRC's strategy of isolating the ROC, the ROC government concluded that the ROC Olympic Committee should not withdraw from the IOC.

In 1981, the ROC government formally accepted the name "Chinese Taipei".[37] A flag bearing the emblem of its Olympic Committee against a white background as the Chinese Taipei Olympic flag was confirmed in January.[38] Based on the Olympic Charter amended at the 82nd IOC Session, an agreement was signed on 23 March in Lausanne by Juan Antonio Samaranch, the president of the IOC, and Shen Chia-ming, the president of the Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee (CTOC).[39][40] The 1981 agreement, also known as the Lausanne Agreement, specified the name, flag and emblem of the CTOC. The CTOC is therefore entitled to be treated on the equal footing as other NOCs. In 1983, the National Flag Anthem of the Republic of China was chosen as the anthem of the Chinese Taipei delegation.[38] Taiwan has competed under this name and flag exclusively at each Games since the 1984 Winter Olympics, as well as at the Paralympics and at other international events (with flags on which the Olympic rings are replaced by a symbol appropriate to the event).

Translation compromise

Chinese

Both the Republic of China (ROC) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) agree to use the English name "Chinese Taipei". The ambiguity of the English word "Chinese" may mean either the state or the culture. The ROC translates "Chinese Taipei" as Zhōnghuá Táiběi (simplified Chinese: 中华台北; traditional Chinese: 中華臺北). The term "Zhonghua" is also used in the ROC's official name and state-owned enterprises. Meanwhile, The PRC translates the name as Zhōngguó Táiběi (simplified Chinese: 中国台北; traditional Chinese: 中國臺北) or literally "Taipei, China", in the same manner as Zhōngguó Xiānggǎng (simplified Chinese: 中国香港; traditional Chinese: 中國香港) ("Hong Kong, China"), explicitly connoting that Taipei is a part of the Chinese state.[2] The disagreement was left unresolved, with both governments using their own translation domestically, until just before the 1990 Asian Games where Taiwan would officially participate under the Chinese Taipei name in a Chinese-language region for the first time, forcing the need for an agreement.[41][42]

In 1989, the two Olympic committees signed a pact in Hong Kong where the PRC agreed to use the ROC's translation in international sports-related occasions hosted in China.[43][42] Domestically, the PRC continues to use its own "Taipei, China" translation.[44] During the 2008 Summer Olympics, Chinese state media used the agreed-upon Zhōnghuá Táiběi both internationally and in domestic press.[45] However, during the 2020 Summer Olympics, state media began using Zhōngguó Táiběi domestically 93% of the time.[46] During the 2022 Winter Olympics opening ceremony, China's state media's broadcast cut away to a clip of General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping when Taiwan's delegation paraded as Zhōnghuá Táiběi. The broadcast in the stadium introduced the team as Zhōnghuá Táiběi, while the television broadcast commentator of China Central Television announced the delegation's name as Zhōngguó Táiběi.[47][48]

The World Health Organization, the international organization to both have Chinese as one of its official languages and have the ROC officially participate, uses Zhōnghuá Táiběi in meeting minutes when the ROC is officially invited,[49] but uses Zhōngguó Táiběi in all other contexts.[50]

Other languages

In French, multiple different names have been officially used. The World Trade Organization officially translates the name as "Taipei Chinois", which has an ambiguous meaning.[51] The text of the IOC's Nagoya Resolution in 1979 used the name "Taipei de Chine" suggesting the state meaning of "Chinese".[52] Before signing the agreement between the IOC and the Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee in 1981, representatives of two committees decided that the French name need not be stated.[27] Only the English name would be used in the future IOC official documents. To this day, Chinese Taipei's page on the French-language IOC's website internally uses both "Taipei de Chine" and "Taipei chinois" (with a lowercase "c") for some image alt text, but the title of the page itself simply uses the English name "Chinese Taipei".[53] When the name is announced during the Parade of Nations, the French and English announcers both repeat the identical name "Chinese Taipei" in English.[54][55]

In East Asian languages that would normally transcribe directly from Chinese, an English transliteration is used instead to sidestep the issue. Thus Japan uses Chainīzu Taipei (チャイニーズ・タイペイ)[56] while South Korea uses Chainiseu Taibei (차이니스 타이베이)[55] for their respective-language announcements during the Olympic Games. Meanwhile, Vietnam uses the direct Sino-Vietnamese transcription to call Chinese Taipei as Đài Bắc Trung Hoa[57] (alternatively Đài Bắc, Trung Hoa with the comma used;[58] chữ Hán: 臺北中華, lit. 'Taipei, Zhonghua') likely due to the cosmetic and grammatical inconvenience when using direct English transliteration or the original English designation in Vietnamese context.

Use of the name

International organizations and forums

Besides the International Olympic Committee and sports organizations, Taiwan is a member economy of APEC and its official name in the organization is "Chinese Taipei".[59] Taiwan's name in the World Trade Organization, "Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu", is frequently abbreviated as Chinese Taipei.[60] It also participated as an invited guest in the World Health Organization (WHO) under the name of Chinese Taipei. The WHO is the only agency of the United Nations that the ROC is able, provided it is invited each year, to participate in since 1971.[61]

The terminology has spilled into apolitical arenas. The PRC has successfully pressured some international organizations and NGOs to refer to the ROC as Chinese Taipei.[62] The International Society for Horticultural Science replaced "Taiwan" with "Chinese Taipei" in designation used for the membership.[63] In a similar case, two Taiwanese medical groups were forced to change the word "Taiwan" in their membership names of ISRRT due to a request by the WHO.[64]

In the Miss World 1998, the government of the PRC pressured the Miss World Organization to rename Miss Republic of China 1998 to "Miss Chinese Taipei".[65] The same happened in 2000, but with the Miss Universe Organization. Three years later at the Miss Universe pageant in Panama, the first official Miss China and Miss Taiwan competed alongside each other for the first time in history, prompting the PRC government to again demand that Miss Taiwan assume the title "Miss Chinese Taipei".[66][67] Today, neither Miss Universe nor Miss World, the two largest pageant contests in the world, allow Taiwan's entrants to compete under the Taiwan label. In 2005, the third-largest pageant contest, Miss Earth, initially allowed Taiwanese contestant to compete as "Miss Taiwan"; a week into the pageant, however, the contestant's sash was updated to "Taiwan ROC". In 2008, Miss Earth changed the country's label to Chinese Taipei.[68]

In Taiwan

The name is controversial in modern Taiwan; many Taiwanese see it as a result of shameful but necessary compromise, and a symbol of oppression that mainland China forced upon them.[9] The title "Chinese Taipei" has been described as confusing, as it leads some people to believe that "Taipei" is a country or that it is located in and/or governed by mainland China. Taiwanese Olympian Chi Cheng has described competing under the name as "aggravating, humiliating and depressing."[69]

Changing demographics and opinions in the country mean that more than 80% of citizens in 2016 see themselves as Taiwanese, not Chinese[70] whereas in 1991 this figure was only 13.6%.[71] This radical upswell in Taiwanese national identity has seen a re-appraisal and removal of "sinocentric" labels and figures established by the government during the period of Martial Law. For sporting events, the ROC team is abbreviated in Taiwan as the "Zhonghua Team" (中華隊). Starting around the time of the 2004 Summer Olympics, there has been a movement in Taiwan to change media references to the team to "Taiwan".[72] During the 2020 Summer Olympics, most TV channels referred to the ROC as the Zhonghua Team while some channels preferred "Taiwan Team" (台灣隊).[73][74]

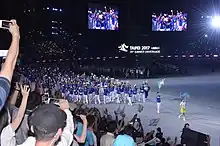

2017 Summer Universiade

Use of the label came under vigorous renewed criticism during the run-up to the 2017 Summer Universiade, hosted in Taiwan.[75] Taiwanese legislators Huang Kuo-chang in particular lambasted the English-language guide to the Universiade for its "absurd" use of the label, illustrating this with statements extracted from the guide rendered nonsensical by their author's insistence on completely avoiding the name "Taiwan" not only when referring to the label under which Taiwanese athletes compete, but even when referring to geographical features such as the island of Taiwan itself.[76] These statements included "Introduction of our Island: ... Chinese Taipei is long and narrow that lies north to south", and "Chinese Taipei is a special island and its Capital Taipei is a great place to experience Taipei's culture." Huang added sarcastically, "Welcome to Taipei, Chinese Taipei!"

In response, the guide was withdrawn and shortly thereafter re-issued with the designation "Taiwan" reinstated.[77][78] Despite these corrections, hundreds of Taiwanese demonstrated in Taipei, demanding that Taiwan cease using "Chinese Taipei" at sporting events.[79][80] In a bid to raise international awareness demonstrators unfurled huge banners reading, in English, "Taiwan is not Chinese Taipei" and "Let Taiwan be Taiwan". Reporting on the controversy at the opening of the Universiade, The New York Times shared Taiwanese indignation over the designation, writing "Imagine if the United States were to hold a major international event, but one of the conditions was for it to call itself British Washington."[81]

2018 referendum

In February 2018, an alliance of civic organizations submitted a proposal to Taiwan's Central Election Commission.[82] The proposed referendum asks if the nation should apply under the name of "Taiwan" for all international sports events, including the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.[83] The proposal influenced the East Asian Olympic Committee (EAOC) to revoke Taichung's right to host the first East Asian Youth Games due to "political factors".[84] An International Olympic Committee (IOC) representative reportedly said this was entirely the decision of the EAOC, and the IOC had no role in the ruling.[85] The IOC also disapproved the altered name and sent three different warnings to the Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee ahead of the referendum vote, concerning the renaming issue which may disbar Taiwan from Olympic competitions.[86][87]

Taiwanese people voted during the 2018 referendum to reject the proposal to change their official Olympic-designated name from Chinese Taipei to Taiwan.[88] The main argument for opposing the name change was worrying that Taiwan may lose its Olympic membership under Chinese pressure, which would result in athletes unable to compete in the Olympics.[9]

Other alternative references to Taiwan

Terminology used to refer to the Republic of China has varied according to the geopolitical situation. Initially, the Republic of China was known simply as "China" until 1971 when the People's Republic of China replaced the Republic of China as the exclusive legitimate representative of "China" at the United Nations.[89][90][91] In order to distinguish the Republic of China from the People's Republic of China, there has been a growing current of support for the use of "Taiwan" in place of "China" to refer to the former.[92][93]

Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu

The World Trade Organization officially uses "Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, and Matsu" for Taiwan, but frequently also uses the shorter name "Chinese Taipei" in official documents.[94]

As with "Chinese Taipei", the ROC and PRC also disagree on the Chinese translation of this name. The ROC uses Tái Pēng Jīn Mǎ Gèbié Guānshuì Lǐngyù (simplified Chinese: 台澎金马个别关税领域; traditional Chinese: 臺澎金馬個別關稅領域, literal translation: TPKM Separate Customs Territory), while the PRC uses Zhōngguó Táiběi Dāndú Guānshuì Qū (simplified Chinese: 中国台北单独关税区; traditional Chinese: 中國台北單獨關稅區, literal translation: Separate Customs Territory of Taipei, China).

Taiwan, Province of China

International organizations in which the PRC participates generally do not recognize Taiwan or allow its membership. Thus, for example, whenever the United Nations makes reference to Taiwan, which does not appear on its member countries list,[95] it uses the designation "Taiwan, Province of China", and organizations that follow UN standards usually do the same, such as the International Organization for Standardization in its listing of ISO 3166-1 country codes. Certain web-based postal address programs also label the country designation name for Taiwan as "Taiwan, Province of China".

Taiwan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs objected to the term together with other names including "Taiwan, China", "Taipei, China" and "Chinese Taiwan" in guidelines issued in 2018.[7][8]

Island of Taiwan/Formosa

The term island of Taiwan or Formosa is used sometimes to avoid any misunderstanding about the Taiwan independence movement just referring to the island.

China or Republic of China

Some non-governmental organizations which the PRC does not participate in continue to use "China" or the "Republic of China". The World Organization of the Scout Movement is one of few international organizations that continue to use the name of "Republic of China", and the ROC affiliate as the Scouts of China. This is because such Scouting in mainland China is very limited or not really active.[96] Likewise, Freemasonry is outlawed in the PRC and thus the Grand Lodge of China is based in Taiwan.

Countries that maintain diplomatic relations with Taiwan, especially the ROC's older diplomatic affiliates, also refer to the ROC as "China" on occasion; for example, during the funeral of Pope John Paul II, the president of the Republic of China, Chen Shui-bian, was seated as part of the French alphabetical seating arrangement as the head of state of "Chine" between the first lady of Brazil, and the president of Cameroon.[97]

Governing authorities on Taiwan

The United States uses the term "governing authorities on Taiwan" instead of the "Republic of China" from 1 January 1979 in the Taiwan Relations Act. Geographically speaking and following the similar content in the earlier defense treaty from 1955, it defines the term "Taiwan" to include, as the context may require, the island of Taiwan (the main Island) and the Pescadores (Penghu). Of the other islands or archipelagos under the control of the Republic of China, Kinmen, the Matsus, etc., are left outside the definition of Taiwan.[98]

Other non-specified areas

The United Nations publishes population projections for each nation, with nations grouped under geographic area; in 2015, the East Asia group contained an entry named "Other non-specified areas" referring to Taiwan. However, the 2017 publication updated the entry's name to the UN's preferred "Taiwan, Province of China".[99][100]

Gallery of Chinese Taipei flags

Flag of the Republic of China, origin of the Blue Sky with a White Sun symbol used in Olympic and other "Chinese Taipei" flags

Flag of the Republic of China, origin of the Blue Sky with a White Sun symbol used in Olympic and other "Chinese Taipei" flags

Chinese Taipei Deaflympics flag

Chinese Taipei Deaflympics flag Chinese Taipei Universiade flag

Chinese Taipei Universiade flag

.svg.png.webp) Chinese Taipei WorldSkills flag

Chinese Taipei WorldSkills flag.svg.png.webp) Chinese Taipei FIRST Robotics Competition flag

Chinese Taipei FIRST Robotics Competition flag Chinese Taipei volleyball flag

Chinese Taipei volleyball flag Flag of Chinese Taipei used in the Overwatch World Cup.

Flag of Chinese Taipei used in the Overwatch World Cup.

See also

References

- Yang, William (6 August 2021). "'Chinese Taipei': Taiwan's Olympic success draws attention to team name". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 23 September 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- Handley, Erin (26 July 2021). "Why will Taiwan compete as Chinese Taipei at the Olympics in Tokyo?". ABC News. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- Zhong, Yang (1 February 2016). "Explaining National Identity Shift in Taiwan". Journal of Contemporary China. 25 (99): 336–352. doi:10.1080/10670564.2015.1104866. ISSN 1067-0564. S2CID 155916226. Archived from the original on 11 April 2023. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Lin, Catherine K. (5 August 2008). "How 'Chinese Taipei' came about". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021.

- "Why is Taiwan not called Taiwan at the Olympics?". Agence France-Presse. 27 July 2021. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Helen Davidson and Jason Lu (2 August 2021). "Will Taiwan's Olympic win over China herald the end of 'Chinese Taipei'?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- "陸宣傳Chinese Taipe為「中國台北」 外交部盼少用". ETtoday (in Chinese). 13 December 2018. Archived from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "政府機關(構)辦理或補助民間團體赴海外出席國際會議或從事國際交流活動有關會籍名稱或參與地位之處理原則" (PDF) (in Chinese). Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). 10 December 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- Chiang, Ying; Chen, Tzu-hsuan (1 June 2021). "What's in a name? Between "Chinese Taipei" and "Taiwan": The contested terrain of sport nationalism in Taiwan". International Review for the Sociology of Sport. 56 (4): 451–470. doi:10.1177/1012690220913231. ISSN 1012-6902. S2CID 225736290.

- Horton, Chris (26 October 2018). "As China Rattles Its Sword, Taiwanese Push a Separate Identity". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- Lucy, Lindell (4 February 2022). "Olympic delegations should side with Taiwan and leave their national flags at home". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 18 February 2022. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Lee, Yimou (3 August 2021). "Taiwan's medals revive debate over use of 'Chinese Taipei'". Reuters. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

- Tiezzi, Shannon (5 August 2021). "Taiwan – Sorry, 'Chinese Taipei' – Is Having a Fantastic Olympics". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 16 December 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2022.

- "Taipei condemns Beijing after youth games suspended". Agence France-Presse. 24 July 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- "Taichung stripped of right to host East Asian Youth Games in Taiwan due to Chinese pressure | Taiwan News". Taiwan News. 24 July 2018. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 25 July 2021.

- "Taiwan's retrocession procedurally clear: Ma". The China Post. CNA. 26 October 2010. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Huang, Tai-lin (22 May 2014). "Lien's campaign TV ads to stress love for Taiwan". Taipei Times. p. 3. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2014.

- Eyal Propper. "How China Views its National Security", Archived 25 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine The Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs, May 2008.

- Li, Chien-Pin (August 2006). "Taiwan's Participation in Inter-Governmental Organizations: An Overview of Its Initiatives". Asian Survey. 46 (4): 597–614. doi:10.1525/as.2006.46.4.597. Archived from the original on 9 April 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- Chan, Gerald (Autumn 1985). "The "Two-Chinas" Problem and the Olympic Formula". Pacific Affairs. 58 (3): 473–490. doi:10.2307/2759241. JSTOR 2759241. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- Cheung, Han (30 August 2015). "An Olympic summer to remember". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "Mexico 68, v.3". LA84 Foundation. Archived from the original on 9 January 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- Meler, Bryan (22 July 2021). "Canada's 'black eye' at the 1976 Montreal Olympics: Two major promises amid the two-Chinas dispute". Yahoo Sports Canada. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "Taiwan controversy at the 1976 Montreal Olympics". CBC. 16 July 1976. Archived from the original on 4 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- "Fiasco at the Olympics". Taiwan Today. 1 September 1976. Archived from the original on 29 June 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- Chang, Chi-hsiung (June 2010). ""De jure" vs. "De facto" Discourse:Battle over ROC Membership with IOC (1960–1964)". Taiwan Historical Research (in Chinese). 17 (2): 85–129. Archived from the original on 28 May 2022. Retrieved 29 June 2022.

- Lin, Catherine Kai-Ping (2008). Nationalism in International Politics: The Republic of China's Sports Foreign Policy-Making and Diplomacy from 1972 to 1981 (PhD). Georgetown University. ProQuest 304642819. Archived from the original on 28 February 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Barker, Philip (10 September 2017). "The first-ever IOC Session in South America was an historic one for many reasons". insidethegames.biz. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- Ritchie, Joe (8 April 1979). "Olympic Group Admits Peking". The Washington Post. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- Pei, Dongguang (2006). "A Question of Names: The Solution to the 'Two Chinas' Issue in Modern Olympic History: The Final Phase, 1971–1984". Cultural Imperialism in Action: Critiques in the Global Olympic Trust: Eighth International Symposium for Olympic Research. International Centre for Olympic Studies. pp. 19–31. Archived from the original on 27 February 2022. Retrieved 27 February 2022.

- Amdur, Neil (30 June 1979). "I.O.C. Paves Way to Let China in Olympics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "China and the Five Rings". Olympic Review. 145: 626. November 1979. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- Amdur, Neil (27 November 1979). "China Plan for the Olympics". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "Olympic Conditions Rejected by Taiwan". The New York Times. 28 November 1979. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- Eaton, Joseph (November 2016). "Reconsidering the 1980 Moscow Olympic Boycott: American Sports Diplomacy in East Asian Perspective". Diplomatic History. 40 (5): 845–864. doi:10.1093/dh/dhw026. JSTOR 26376807. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- Liu, Hung-Yu (June 2007). "A Study of the Signing of Lausanne Agreement between IOC and Chinese Taipei" (PDF). Journal of Sport Culture (in Chinese). 1 (1): 53–83. doi:10.29818/SS.200706.0003. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2022. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- Hung, Joe (10 January 2002). "Chinese Taipei". National Policy Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- Liu, Chin-Ping (2007). 1981年奧會模式簽訂之始末 (PDF) (in Chinese). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 March 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- "The International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced today that Taiwan..." UPI. 23 March 1981. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "1981 Agreement with IOC" (PDF). Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee. 23 March 1981. Archived from the original on 12 September 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- Brownell, Susan (14 June 2008). "Could China stop Taiwan from coming to the Olympic Games?". History News Network. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- "我國國際暨兩岸體育交流之研究" (PDF) (in Chinese). Sports Affairs Council of the Executive Yuan. June 1999. pp. 55–63. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2021.

- Lu, Pengqiao (23 May 2017). "China Is Undermining Its Own Taiwan Strategy". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "Mainland clarifies name issue of Taiwan team". china.org.cn. Xinhua News Agency. 24 July 2008. Archived from the original on 27 September 2022. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- "Beijing fiddles Taiwan's name for Olympics - Taipei Times". www.taipeitimes.com. 10 July 2008. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- Yu-fu, Chen; Pan, Jason (8 August 2021). "Beijing seeks to downgrade Taiwan's status: report". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 7 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- "Chinese Taipei were forced to march in the Ceremony". insidethegames.biz. 4 February 2022. Archived from the original on 6 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "China Knew It Couldn't Escape Politics at the Olympics Opening Ceremony. It Didn't Try". Time. 4 February 2022. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- "第六十四届世界卫生大会" (PDF) (in Chinese). WHO. 2 May 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 November 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "预防自杀全球要务" (PDF) (in Chinese). WHO. 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Le Territoire douanier distinct de Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen, Matsu (Taipei Chinois) et l'OMC". World Trade Organization (in French). Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- "La Chine et les cinq anneaux". Revue Olympique (in French). 145: 626. November 1979. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 7 February 2022.

- "Chinese Taipei - Comité National Olympique (CNO)". International Olympic Committee. 27 July 2021. Archived from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- "Rio 2016 Opening Ceremony". International Olympic Committee. 26 September 2016. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022 – via Youtube.

- "PyeongChang 2018 Opening Ceremony". International Olympic Committee. 30 March 2020. Archived from the original on 14 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022 – via Youtube.

- Nojima, Tsuyoshi (4 February 2022). "なぜ台湾は五輪で「チャイニーズ・タイペイ」なのか". Yahoo Japan (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- "VFF - HLV Mai Đức Chung: Đội tuyển Nữ Việt Nam tự tin giành vé trước Đài Bắc Trung Hoa để đi World Cup". Vietnam Football Federation (in Vietnamese). 5 February 2022. Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- Government, Viet Nam (6 February 2022). "NHỮNG NGÔI SAO VÀNG 'BAY' VÀO LỊCH SỬ!". Vietnam Government News (in Vietnamese). Archived from the original on 19 February 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2023.

- "APEC FAQ: Who are the members of APEC?". Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation. 11 November 2008. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008.

- "Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu (Chinese Taipei) and the WTO". World Trade Organization. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- Reid, Katie (18 May 2009). "Taiwan hopes WHO assembly will help boost its profile". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- "Stilblüten" (in German). Archived from the original on 14 June 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- "Instances of Mainland China's Interference with Taiwan's International Presence, 2010". Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of China (Taiwan). Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- Lee, I-chia (11 January 2021). "Society deletes Taiwan references". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 12 February 2022. Retrieved 12 February 2022.

- "Miss World 2008 Contestants". Miss World. 11 November 2008. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014.

- "Chen Szu-yu with her two sashes". Archived from the original on 14 October 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- "Beauty queen renamed". Taipei Times. 23 May 2003. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2012.

- "85 Beauties Set Their Sights on 'Miss Earth 2008' Crown". OhmyNews. 11 November 2008. Archived from the original on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- Davidson, Helen; Lu, Jason (2 August 2021). "Will Taiwan's Olympic win over China herald the end of 'Chinese Taipei'?". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 August 2021. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- "Taiwanese identity reaches record high". Taipei Times. 28 May 2016. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- Chang, Rich (12 March 2006). "'Taiwan identity' growing: study". Taipei Times. p. 3. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- "Rest in peace, 'Chinese Taipei'". Taipei Times. 1 September 2004. Archived from the original on 15 October 2008. Retrieved 22 November 2008.

- "媒體監看報告:國內媒體從頭到尾稱「台灣隊」僅一家 多呈「精神分裂」狀況" (in Chinese). Newtalk. 4 August 2021. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "統計公布!沃草:這2電視台東京奧運期間從不稱「台灣隊」". The Liberty Times (in Chinese). 24 August 2021. Archived from the original on 7 February 2022. Retrieved 8 February 2022.

- "Taiwan is sick and tired of competing as 'Chinese Taipei' in global sporting events". Quartz. 8 August 2017. Archived from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- "NPP blasts 'absurd' English guide to Universiade". Taipei Times. 9 August 2017. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- "Universiade: 'Taiwan' back in English media guide". Focus Taiwan. 11 August 2017. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Taipei Universiade: 'Chinese Taipei' brochure slammed". Taipei Times. 13 August 2017. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "Taipei Universiade: Groups call for use of 'Taiwan' at Universiade". Taipei Times. 13 August 2017. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "'Taiwan is not Chinese Taipei' and 'Let Taiwan be Taiwan' banners". Taipei Times. 13 August 2017. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- "What's in a Name? For Taiwan, Preparing for the Spotlight, a Lot". The New York Times. 16 August 2017. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- Tai-lin, Huang (9 July 2018). "INTERVIEW: Push for Olympic name change not political". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- Pan, Jason (1 August 2018). "Groups urge changing name of Olympic team". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- Hsu, Stacy (25 July 2018). "Taichung loses right to host Games". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- DeAeth, Duncan (31 July 2018). "Intl Olympic Committee approves of China's decision to cancel 2019 Youth Games in Taiwan". Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- Deaeth, Duncan (20 November 2018). "IOC threatens to disbar Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee". Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Shan, Shelley (20 November 2018). "ELECTIONS: IOC sends third warning on name change". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- Strong, Matthew (24 November 2018). "Push to use name "Taiwan" instead of "Chinese Taipei" at Tokyo Olympics falters". Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 28 June 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- 林義鈞. 第三章、國際因素對台灣認同的影響 Archived 30 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. 國立政治大學. 2003年 [2016年2月24日] (in Chinese).

- 潘俊鐘. 第四章 台灣民眾族群認同、國家認同與統獨態度 Archived 30 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine. 國立政治大學. 2003年 [2016年2月24日] (in Chinese).

- 行政院研究發展考核委員會 (1 July 2009). 《政府開放政策對兩岸關係發展之影響與展望》. 臺灣: 威秀代理. pp. 第114頁至第115頁.

- "「聯合國學者專家訪華團」一行8人應邀訪華 - 新聞稿及聲明". 參與國際組織. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- "行政院全球資訊網". 2.16.886.101.20003. 1 December 2011. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016.

- "Member Information: Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu (Chinese Taipei) and the WTO". World Trade Organization. 18 November 2008. Archived from the original on 29 November 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- "United Nations Infonation". The United Nations. 11 November 2008. Archived from the original on 5 April 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2017.

- Although such organizations are established in the mainland, there is no or less governmental or CPC support to them.

- "Extraordinary Missions present at the Solemn Funeral of Pope John Paul II". www.vatican.va. Retrieved 22 April 2023.

- 陳鴻瑜 (20 July 2008). 台灣法律地位之演變(1973-2005) (PDF) (Report). 臺北縣: 淡江大學東南亞研究所. p. 9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 October 2017. Retrieved 14 May 2022.

對於台灣的定義是規定在第十五條第二款:「台灣一詞:包括台灣島及澎湖群島,這些島上的居民,依據此等島所實施的法律而成立的公司或其他法人,以及1979年1月1日前美國所承認為中華民國的台灣統治當局與任何繼位統治當局(包括其政治與執政機構。)」從而可知,台灣關係法所規範的台灣只包括台灣和澎湖群島,並不包括金門、馬祖等外島。

- Basten, Stuart (2013). "Redefining "old age" and "dependency" in the East Asian social policy narrative". Asian Social Policy and Social Work Review. Archived from the original on 27 August 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- "2015 Revision of World Population Prospects". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Archived from the original on 27 January 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

External links

Media related to Flags of Chinese Taipei at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Flags of Chinese Taipei at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of Chinese Taipei at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Chinese Taipei at Wiktionary- (in Chinese) 國民體育季刊 No. 156. Focus Topic: Olympic Model

- Chinese Taipei Olympic Committee Official Website