Abdul Karim (the Munshi)

Mohammed Abdul Karim CVO CIE (1863 — 20 April 1909), also known as "the Munshi", was an Indian attendant of Queen Victoria. He served her during the final fourteen years of her reign, gaining her maternal affection over that time.

Mohammed Abdul Karim | |

|---|---|

منشى عبدالكريم | |

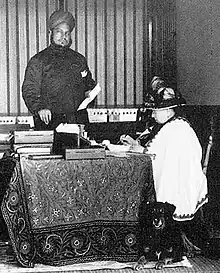

Portrait by Rudolf Swoboda, 1888 | |

| Indian Secretary to Queen Victoria | |

| In office 1892–1901 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1863 Lalitpur, North-Western Provinces, British India |

| Died | 20 April 1909 (aged 46)[1] Agra, United Provinces, British India |

| Spouse | Rashidan Karim |

Karim was born the son of a hospital assistant at Lalitpur, near Jhansi in British India. In 1887, the year of Victoria's Golden Jubilee, Karim was one of two Indians selected to become servants to the Queen. Victoria came to like him a great deal and gave him the title of "Munshi" ("clerk" or "teacher"). Victoria appointed him to be her Indian Secretary, showered him with honours, and obtained a land grant for him in India.

The close platonic[2][3] relationship between Karim and the Queen led to friction within the Royal Household, the other members of which felt themselves to be superior to him. The Queen insisted on taking Karim with her on her travels, which caused arguments between her and her other attendants. Following Victoria's death in 1901, her successor, Edward VII, returned Karim to India and ordered the confiscation and destruction of the Munshi's correspondence with Victoria. Karim subsequently lived quietly near Agra, on the estate that Victoria had arranged for him, until his death at the age of 46.

Early life

Mohammed Abdul Karim was born into a Muslim family at Lalitpur near Jhansi in 1863.[4] His father, Haji Mohammed Waziruddin, was a hospital assistant stationed with the Central India Horse, a British cavalry regiment.[5] Karim had one older brother, Abdul Aziz, and four younger sisters. He was taught Persian and Urdu privately[6] and, as a teenager, travelled across North India and into Afghanistan.[7] Karim's father participated in the conclusive march to Kandahar, which ended the Second Anglo-Afghan War, in August 1880. After the war, Karim's father transferred from the Central India Horse to a civilian position at the Central Jail in Agra, while Karim worked as a vakil ("agent" or "representative") for the Nawab of Jaora in the Agency of Agar. After three years in Agar, Karim resigned and moved to Agra, to become a vernacular clerk at the jail. His father arranged a marriage between Karim and the sister of a fellow worker.[8]

Prisoners in the Agra jail were trained and kept employed as carpet weavers as part of their rehabilitation. In 1886, 34 convicts travelled to London to demonstrate carpet weaving at the Colonial and Indian Exhibition in South Kensington. Karim did not accompany the prisoners, but assisted Jail Superintendent John Tyler in organising the trip, and helped to select the carpets and weavers. When Queen Victoria visited the exhibition, Tyler gave her a gift of two gold bracelets, again chosen with the assistance of Karim.[9] The Queen had a longstanding interest in her Indian territories and wished to employ some Indian servants for her Golden Jubilee. She asked Tyler to recruit two attendants who would be employed for a year.[10] Karim was hastily coached in British manners and in the English language and sent to England, along with Mohammed Buksh. Major-General Thomas Dennehy, who was about to be appointed to the Royal Household, had previously employed Buksh as a servant.[11] It was planned that the two Indian men would initially wait at table, and learn to do other tasks.[12]

Royal servant

After a journey by rail from Agra to Bombay and by mail steamer to Britain, Karim and Buksh arrived at Windsor Castle in June 1887.[13] They were put under the charge of Major-General Dennehy and first served the Queen at breakfast in Frogmore House at Windsor on 23 June 1887. The Queen described Karim in her diary for that day: "The other, much younger, is much lighter [than Buksh], tall, and with a fine serious countenance. His father is a native doctor at Agra. They both kissed my feet."[14]

Five days later, the Queen noted that "The Indians always wait now and do so, so well and quietly."[15] On 3 August, she wrote: "I am learning a few words of Hindustani to speak to my servants. It is a great interest to me for both the language and the people, I have naturally never come into real contact with before."[16] On 20 August she had some "excellent curry" made by one of the servants.[17] By 30 August Karim was teaching her Urdu,[18] which she used during an audience in December to greet the Maharani Chimnabai of Baroda.[19]

Victoria took a great liking to Karim and ordered that he was to be given additional instruction in the English language.[20] By February 1888 he had "learnt English wonderfully" according to Victoria.[21] After he complained to the Queen that he had been a clerk in India and thus menial work as a waiter was beneath him,[22][23] he was promoted to the position of "Munshi" in August 1888.[24] In her journal, the Queen writes that she made this change so that he would stay: "I particularly wish to retain his services as he helps me in studying Hindustani, which interests me very much, & he is very intelligent & useful."[25] Photographs of him waiting at table were destroyed and he became the first Indian personal clerk to the Queen.[26] Buksh remained in the Queen's service, but only as a khidmatgar or table servant,[27] until his death at Windsor in 1899.[28]

According to Karim biographer Sushila Anand, the Queen's own letters testify that "her discussions with the Munshi were wide-ranging—philosophical, political, and practical. Both head and heart were engaged. There is no doubt that the Queen found in Abdul Karim a connection with a world that was fascinatingly alien, and a confidant who would not feed her the official line."[29] Karim was placed in charge of the other Indian servants and made responsible for their accounts. Victoria praised him in her letters and journal. "I am so very fond of him" she wrote, "He is so good & gentle & understanding all I want & is a real comfort to me."[30] She admired "her personal Indian clerk & Munshi, who is an excellent, clever, truly p[i]ous & very refined gentle man, who says, 'God ordered it' ... God's Orders is what they implicitly obey! Such faith as theirs & such conscientiousness set us a g[rea]t example."[31] At Balmoral Castle, the Queen's Scottish estate, Karim was allocated the room previously occupied by John Brown, a favourite servant of the Queen who had died in 1883.[32] Despite the serious and dignified manner that Karim presented to the outside world, the Queen wrote that "he is very friendly and cheerful with the Queen's maids and laughs and even jokes now—and invited them to come and see all his fine things offering them fruit cake to eat".[33]

Household hostility

In November 1888, Karim was given four months' leave to return to India, during which time he visited his father. Karim wrote to Victoria that his father, who was due to retire, had hopes of a pension and that his former employer, John Tyler, was angling for promotion. As a result, throughout the first six months of 1889, Victoria wrote to the Viceroy of India, Lord Lansdowne, demanding action on Waziruddin's pension and Tyler's promotion. The Viceroy was reluctant to pursue the issues because Waziruddin had told the local governor, Sir Auckland Colvin, that he desired only gratitude and also because Tyler had a reputation for tactless behaviour and bad-tempered remarks.[34][35]

Karim's swift rise began to create jealousy and discontent among the members of the Royal Household, who would normally never mingle socially with Indians below the rank of prince. The Queen expected them to welcome Karim, an Indian of ordinary origin, into their midst, but they were not willing to do so.[33] Karim, for his part, expected to be treated as an equal. When Albert Edward, Prince of Wales (later Edward VII), hosted an entertainment for the Queen at his home in Sandringham on 26 April 1889, Karim found he had been allocated a seat with the servants. Feeling insulted, he retired to his room. The Queen took his part, stating that he should have been seated among the Household.[36] When the Queen attended the Braemar Games in 1890, her son Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, approached the Queen's private secretary, Sir Henry Ponsonby, in outrage after he saw the Munshi among the gentry. Ponsonby suggested that as it was "by the Queen's order", the Duke should approach the Queen about it.[37] "This entirely shut him up", noted Ponsonby.[38]

Victoria biographer Carolly Erickson described the situation:

The rapid advancement and personal arrogance of the Munshi would inevitably have led to his unpopularity, but the fact of his race made all emotions run hotter against him. Racialism was a scourge of the age; it went hand in hand with belief in the appropriateness of Britain's global dominion. For a dark-skinned Indian to be put very nearly on a level with the queen's white servants was all but intolerable, for him to eat at the same table as them, to share in their daily lives was viewed as an outrage. Yet the queen was determined to impose harmony on her household. Race hatred was intolerable to her, and the "dear good Munshi" deserving of nothing but respect.[39]

When complaints were brought to her, Victoria refused to believe any negative comments about Karim.[40] She dismissed concerns about his behaviour, deemed high-handed by Household and staff, as "very wrong".[41] In June 1889, Karim's brother-in-law, Hourmet Ali, sold one of Victoria's brooches to a jeweller in Windsor. She accepted Karim's explanation that Ali had found the brooch and that it was customary in India to keep anything that one found, whereas the rest of the Household thought Ali had stolen it.[42] In July, Karim was assigned the room previously occupied by James Reid, Victoria's physician, and given the use of a private sitting room.[43]

The Queen, influenced by the Munshi, continued to write to Lord Lansdowne on the issue of Tyler's promotion and the administration of India. She expressed reservations on the introduction of elected councils on the basis that Muslims would not win many seats because they were in the minority, and urged that Hindu feasts be rescheduled so as not to conflict with Muslim ones. Lansdowne dismissed the latter suggestion as potentially divisive,[44] but appointed Tyler Acting Inspector General of Prisons in September 1889.[45]

To the Household's surprise and concern, during Victoria's stay at Balmoral in September 1889, she and Karim stayed for one night at a remote house on the estate, Glas-allt-Shiel at Loch Muick. Victoria had often been there with Brown and after his death had sworn never to stay there again.[45] In early 1890, Karim fell ill with an inflamed boil on his neck and Victoria instructed Reid, her physician, to attend to Karim.[46] She wrote to Reid expressing her anxiety and explaining that she felt responsible for the welfare of her Indian servants because they were so far from their own land.[47] Reid performed an operation to open and drain the swelling, after which Karim recovered.[47] Reid wrote on 1 March 1890 that the Queen was "visiting Abdul twice daily, in his room taking Hindustani lessons, signing her boxes, examining his neck, smoothing his pillows, etc."[48]

Land grant and family matters

_-_The_Munshi_Abdul_Karim_(1863-1909)_-_RCIN_406915_-_Royal_Collection.jpg.webp)

In 1890, the Queen had Karim's portrait painted by Heinrich von Angeli. According to the Queen, von Angeli was keen to paint Karim as he had never painted an Indian before and "was so struck with his handsome face and colouring".[49] On 11 July, she wrote to Lansdowne, and the Secretary of State for India, Lord Cross, for "a grant of land to her really exemplary and excellent young Munshi, Hafiz Abdul Karim".[50] The ageing Queen did not trust her relatives and the Royal Household to look after the Munshi after she was gone, and so sought to secure his future.[51] Lansdowne replied that grants of land were given only to soldiers, and then only in cases of long and meritorious service. Nevertheless, the Viceroy agreed to find a grant for Karim that would provide about 600 rupees annually, the same amount that an old soldier could expect after performing exceptionally.[52] Victoria wrote to Lansdowne repeatedly between July and October, pressuring him on the land grant. Apart from wasteland, there was little government-controlled land near Agra; thus Lansdowne was having trouble finding a suitable plot.[53] On 30 October, the Munshi left Balmoral for four months' leave in India, travelling on the same ship as Lady Lansdowne. On the same day, Lord Lansdowne telegraphed the Queen to let her know that a grant of land in the suburbs of Agra had been arranged.[54] Lansdowne made a point of informing the Queen:

... quite recently one of the men who at the peril of his life, and under a withering fire helped to blow up the Kashmiri Gate of Delhi in the Mutiny, received, on his retirement from the service, a grant of land yielding only Rs 250 for life. Abdul Karim, at the age of 26, had received a perpetual grant of land representing an income of more than double that amount in recognition of his services as a member of your Majesty's Household.[55]

Lansdowne visited Agra in November 1890. He and the Munshi met, and Lansdowne arranged for Karim to be seated with the viceregal staff during a durbar.[56] Lansdowne met both the Munshi and Waziruddin privately, and Lady Lansdowne met his wife and mother-in-law, who were smuggled into the Viceroy's camp in secrecy to comply with rules of purdah.[57]

In 1891, after Karim's return to Britain, he asked Reid to send his father a large quantity of medicinal compounds, which included strychnine, chloral hydrate, morphine, and many other poisons. Reid calculated that the amount requested was "amply sufficient to kill 12,000 to 15,000 full grown men or an enormously large number of children" and consequently refused.[58] Instead, Reid persuaded the Queen that the chemicals should be obtained at her expense by the appropriate authorities in India.[58] In June 1892, Waziruddin visited Britain and stayed at both Balmoral and Windsor Castles.[59] He retired in 1893 and in the New Year Honours 1894 he was rewarded, to Victoria's satisfaction, with the title of Khan Bahadur, which Lansdowne noted was "one which under ordinary circumstances the Doctor [could] not have ventured to expect".[60]

In May 1892, the Munshi returned to India on six months' leave; on his return, his wife and mother-in-law accompanied him. Both women were shrouded from head to foot and travelled in railway compartments with drawn curtains. Victoria wrote, "the two Indian ladies ... who are, I believe, the first Mohammedan purdah ladies who ever came over ... keep their custom of complete seclusion and of being entirely covered when they go out, except for the holes for their eyes."[61] As a woman, Victoria saw them without veils.[62] The Munshi and his family were housed in cottages at Windsor, Balmoral and Osborne, the Queen's retreat on the Isle of Wight.[63] Victoria visited regularly, usually bringing her female guests, including the Empress of Russia and the Princess of Wales, to meet the Munshi's female relatives.[64] One visitor, Marie Mallet, the Queen's maid-in-waiting and wife of civil servant Bernard Mallet, recorded:

I have just been to see the Munshi's wife (by Royal Command). She is fat and not uncomely, a delicate shade of chocolate and gorgeously attired, rings on her fingers, rings on her nose, a pocket mirror set in turquoises on her thumb and every feasible part of her person hung with chains and bracelets and ear-rings, a rose-pink veil on her head bordered with heavy gold and splendid silk and satin swathings round her person. She speaks English in a limited manner ..."[65]

Reid never saw Mrs Karim unveiled, though he claimed that whenever he was called to examine her, a different tongue was protruded from behind the veil for his inspection.[66]

In 1892, the Munshi's name began to appear in the Court Circular among the names of officials accompanying the Queen on her annual March trip to the French Riviera.[32] As usual, Victoria spent Christmas 1892 at Osborne House, where the Munshi, as he had in previous years, participated in tableaux vivants arranged as entertainment.[67] The following year, during Victoria's annual holiday in continental Europe, he was presented to King Umberto I of Italy.[68] In the words of a contemporary newspaper account, "The King did not understand why this magnificent and imposing Hindoo should have been formally presented to him. The popular idea in Italy is that the Munshi is a captive Indian prince, who is taken about by the Queen as an outward and visible sign of Her Majesty's supremacy in the East."[69]

By 1893, Victoria was sending notes to Karim signed in Urdu.[63] She often signed off her letters to Karim as "your affectionate mother, VRI"[70] or "your truly devoted and fond loving mother, VRI".[71]

Travels and Diamond Jubilee

The Munshi was perceived to have taken advantage of his position as the Queen's favourite, and to have risen above his status as a menial clerk, causing resentment in the court. On a journey through Italy, he published an advertisement in the Florence Gazette stating that "[h]e is belonging to a good and highly respectful famiely [sic]".[32] Karim refused to travel with the other Indians and appropriated the maid's bathroom for his exclusive use.[72] On a visit to Coburg, he refused to attend the marriage of Victoria's granddaughter Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, because her father, Victoria's son Alfred, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, assigned him a seat in the gallery with the servants.[73] Confronted by the opposition of her family and retainers, the Queen defended her favourite.[74] She wrote to her private secretary Sir Henry Ponsonby: "to make out that the poor good Munshi is so low is really outrageous & in a country like England quite out of place ... She has known 2 Archbishops who were sons respectively of a Butcher & a Grocer ... Abdul's father saw good & honourable service as a Dr & he [Karim] feels cut to the heart at being thus spoken of."[75]

Lord Lansdowne's term of office ended in 1894, and he was replaced by Lord Elgin. Ponsonby's son Frederick was Elgin's aide-de-camp in India for a short time before being appointed an equerry to Victoria. Victoria asked Frederick to visit Waziruddin, the "surgeon-general" at Agra.[76] On his return to Britain, Frederick told Victoria that Waziruddin "was not the surgeon-general but only the apothecary at the jail", which Victoria "stoutly denied" saying Frederick "must have seen the wrong man".[76] To "mark her displeasure", Victoria did not invite Frederick to dinner for a year.[76]

At Christmas 1894, the Munshi sent Lord Elgin a sentimental greeting card, which to Victoria's dismay went unacknowledged.[77] Through Frederick Ponsonby, she complained to Elgin, who replied that he did "not imagine that any acknowledgement was necessary, or that the Queen would expect him to send one", pointing out "how impossible it would be for an Indian Viceroy to enter into correspondence of this kind".[78]

Frederick wrote to Elgin in January 1895 that Karim was deeply unpopular in the Household, and that he occupied "very much the same position as John Brown used to".[79] Princesses Louise and Beatrice, Prince Henry of Battenberg, Prime Minister Lord Rosebery, and Secretary of State for India Henry Fowler had all raised concerns about Karim with the Queen, who "refused to listen to what they had to say but was very angry, so as you see the Munshi is a sort of pet, like a dog or cat which the Queen will not willingly give up".[79] Elgin was warned by both Ponsonby and the India Office that the Queen gave his letters to the Munshi to read, and that consequently his correspondence to her should not be of a confidential nature.[80] Victoria's advisors feared Karim's association with Rafiuddin Ahmed, an Indian political activist resident in London who was connected to the Muslim Patriotic League. They suspected that Ahmed extracted confidential information from Karim to pass onto the Amir of Afghanistan, Abdur Rahman Khan.[81] There is no indication that these fears were well-founded, or that the Munshi was ever indiscreet.[82]

During the Queen's annual holiday in the French Riviera, in March 1895, the local newspapers ran articles on Le Munchy, secrétaire indien and le professor de la Reine, which according to Frederick Ponsonby were instigated by Karim.[83] In the Queen's 1895 Birthday Honours that May, Karim was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Indian Empire (CIE),[84] despite the opposition of both Rosebery and Fowler.[85] Tyler was astonished by Karim's elevation when he visited England the following month.[85]

After the 1895 United Kingdom general election, Rosebery and Fowler were replaced by Lord Salisbury and Lord George Hamilton respectively. Hamilton thought Karim was not as dangerous as some supposed but that he was "a stupid man, and on that account he may become a tool in the hands of other men."[86] In early 1896, Karim returned to India on six months' leave, and Hamilton and Elgin placed him under "unobtrusive" surveillance.[86] They dared not be too obvious lest the Munshi notice and complain to the Queen.[87] Despite fears that Karim might meet with hostile agents, his visit home appears to have been uneventful.[88]

He left Bombay for Britain in August 1896, bringing with him his young nephew, Mohammed Abdul Rashid.[89] Karim had no children of his own. Victoria had arranged for a female doctor to examine the Munshi's wife in December 1893, as the couple had been trying to conceive without success.[90] By 1897, according to Reid, Karim had gonorrhea.[91]

In March 1897 as members of the Household prepared to depart for Cimiez for the Queen's annual visit, they insisted that Karim not accompany the royal party, and decided to resign if he did so. When Harriet Phipps, one of the Queen's maids of honour, informed her of the collective decision, the Queen swept the contents of her desk onto the floor in a fury.[92] The Household backed down, but the holiday was marred by increased resentment and rows between the Household and Victoria. She thought their distrust and dislike of Karim was motivated by "race prejudice" and jealousy.[93] When Rafiuddin Ahmed joined Karim in Cimiez, the Household forced him to leave, which Victoria thought "disgraceful", and she asked the prime minister to issue an apology to Ahmed, explaining he was only excluded because he had written articles in newspapers and pressmen were not permitted.[94] Ponsonby wrote in late April, "[the Munshi] happens to be a thoroughly stupid and uneducated man, and his one idea in life seems to be to do nothing and to eat as much as he can."[93] Reid warned the Queen that her attachment to Karim had led to questions about her sanity,[95] and Hamilton telegraphed to Elgin requesting information on the Munshi and his family in an effort to discredit him.[96] On receiving Elgin's reply that they were "Respectable and trustworthy ... but position of family humble",[96] Hamilton concluded "the Munshi has done nothing to my knowledge which is reprehensible or deserving of official stricture ... enquiries w[oul]d not be right, unless they were in connection with some definite statement or accusation." He did, however, authorise further investigation of the "Mohamedan intriguer named Rafiuddin".[97] Nothing was ever proven against Ahmed,[98] who later became a Bombay government official and was knighted in 1932.[99] The effect of the row, in Hamilton's words, was "to put him [the Munshi] more into his humble place, and his influence will not be the same in the future".[100]

After the distress of 1897, Victoria sought to reassure the Munshi. "I have in my Testamentary arrangements secured your comfort," she wrote to him, "and have constantly thought of you well. The long letter I enclose which was written nearly a month ago is entirely and solely my own idea, not a human being will ever know of it or what you answer me. If you can't read it I will help you and then burn it at once."[102] She told Reid the squabbles placed her and the Munshi under strain, which he replied was unlikely in the latter's case "judging from his robust appearance and undiminished stoutness".[103] Lord Salisbury told Reid he thought it unlikely in her case too, and that she secretly enjoyed the arguments because they were "the only form of excitement she can have".[104]

Reid seems to have joined with the other Household members in complaining about the Munshi, for the Queen wrote to him, "I thought you stood between me and them, but now I feel that you chime in with the rest."[105] In 1899, members of the Household again insisted that Karim not accompany the royal party when the Queen took her annual holiday at Cimiez. The Queen duly had Karim remain at Windsor, then when the party had settled into the Excelsior Regina hotel, wired Karim to come and join them.[106]

Later life

In late 1898 Karim's purchase of a parcel of land adjacent to his earlier grant was finalised; he had become a wealthy man.[107] Reid claimed in his diary that he had challenged Karim over his financial dealings: "You have told the Queen that in India no receipts are given for money, and therefore you ought not to give any to Sir F Edwards [Keeper of the Privy Purse]. This is a lie and means that you wish to cheat the Queen."[108] The Munshi told the Queen he would provide receipts in answer to the allegations, and Victoria wrote to Reid dismissing the accusations, calling them "shameful".[109]

Karim asked Victoria for the title of "Nawab", the Indian equivalent of a peer, and to appoint him a Knight Commander of the Order of the Indian Empire (KCIE), which would make him "Sir Abdul Karim". A horrified Elgin suggested instead that she make Karim a Member of the Royal Victorian Order (MVO), which was in her personal gift, bestowed no title, and would have little political implication in India.[110] Privy Purse Sir Fleetwood Edwards and Prime Minister Lord Salisbury advised against even the lower honour.[111] Nevertheless, in 1899, on the occasion of her 80th birthday, Victoria appointed Karim a commander of the order (CVO), a rank intermediate between member and knight.[112]

The Munshi returned to India in November 1899 for a year. Waziruddin, described as "a courtly old gentleman" by Lord Curzon, Elgin's replacement as Viceroy, died in June 1900.[113] By the time Karim returned to Britain in November 1900 Victoria had visibly aged, and her health was failing. Within three months she had died.[114]

After Victoria's death, her son, Edward VII, dismissed the Munshi and his relations from court and had them sent back to India. However, Edward did allow the Munshi to be the last to view Victoria's body before her casket was closed,[115] and to be part of her funeral procession.[116] Almost all of the correspondence between Victoria and Karim was burned on Edward's orders.[117] Lady Curzon wrote on 9 August 1901,

Charlotte Knollys told me that the Munshi bogie which had frightened all the household at Windsor for many years had proved a ridiculous farce, as the poor man had not only given up all his letters but even the photos signed by Queen and had returned to India like a whipped hound. All the Indian servants have gone back so now there is no Oriental picture & queerness at Court.[118]

In 1905–06, George, Prince of Wales, visited India and wrote to the King from Agra, "In the evening we saw the Munshi. He has not grown more beautiful and is getting fat. I must say he was most civil and humble and really pleased to see us. He wore his C.V.O. which I had no idea he had got. I am told he lives quietly here and gives no trouble at all."[119]

The Munshi died at his home, Karim Lodge, on his estate in Agra on 20 April 1909.[120] He was survived by two wives,[121] and was interred in a pagoda-like mausoleum in the Panchkuin Kabaristan cemetery in Agra beside his father.[122]

On the instructions of Edward VII, the Commissioner of Agra, W. H. Cobb, visited Karim Lodge to retrieve any remaining correspondence between the Munshi and the Queen or her Household, which was confiscated and sent to the King.[123] The Viceroy (by then Lord Minto), Lieutenant-Governor John Hewitt, and India Office civil servants disapproved of the seizure, and recommended that the letters be returned.[124] Eventually the King returned four, on condition that they would be sent back to him on the death of the Munshi's first wife.[125] Karim's family, who had emigrated to Pakistan during the Partition, kept his diary and some of his correspondence from the time concealed until 2010, when it was made public.[126]

Legacy

As the Munshi had no children, his nephews and grandnephews inherited his wealth and properties. The Munshi's family continued to reside in Agra until Indian independence and the partition of India in August 1947, after which they emigrated to Karachi, Pakistan. The estate, including Karim Lodge, was confiscated by the Indian government and distributed among Hindu refugees from Pakistan. Half of Karim Lodge was subsequently divided into two individual residences, with the remaining half becoming a nursing home and doctor's office.[127]

Until the publication of Frederick Ponsonby's memoirs in 1951, there was little biographical material on the Munshi.[128] Scholarly examination of his life and relationship with Victoria began around the 1960s,[129] focusing on the Munshi as "an illustration of race and class prejudice in Victorian England".[130] Mary Lutyens, in editing the diary of her grandmother Edith (wife of Lord Lytton, Viceroy of India 1876–80), concluded, "Though one can understand that the Munshi was disliked, as favourites nearly always are ... One cannot help feeling that the repugnance with which he was regarded by the Household was based mostly on snobbery and colour prejudice."[131] Victoria biographer Elizabeth Longford wrote, "Abdul Karim stirred once more that same royal imagination which had magnified the virtues of John Brown ... Nevertheless, [it] insinuated into her confidence an inferior person, while it increased the nation's dizzy infatuation with an inferior dream, the dream of Colonial Empire."[132]

Historians agree with the suspicions of her Household that the Munshi influenced the Queen's opinions on Indian issues, biasing her against Hindus and favouring Muslims.[133] But suspicions that he passed secrets to Rafiuddin Ahmed are discounted. Victoria asserted that "no political papers of any kind are ever in the Munshi's hands, even in her presence. He only helps her to read words which she cannot read or merely ordinary submissions on warrants for signature. He does not read English fluently enough to be able to read anything of importance."[134] Consequently, it is thought unlikely that he could have influenced the government's Indian policy or provided useful information to Muslim activists.[130]

The 2017 feature film Victoria & Abdul, directed by Stephen Frears and starring Ali Fazal as Abdul Karim and Judi Dench as Queen Victoria, offers a fictionalised version of the relationship between Karim and the Queen.[2][135]

Notes and references

- Qureshi, Siraj (20 April 2016). "Death anniversary of Queen Victoria's personal secretary Munshi Abdul Kareem observed". India Today. Archived from the original on 24 May 2021. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- Miller, Julie (22 September 2017). "Victoria and Abdul: The Truth About the Queen's Controversial Relationship". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- Mack, Tom (11 September 2017). "Queen Victoria confidante Abdul Karim's descendant 'honoured' by royal connection". Leicester Mercury. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- Basu, p. 22

- Basu, pp. 22–23

- Basu, p. 23

- Basu, pp. 23–24

- Basu, p. 24

- Basu, p. 25

- Victoria to Lord Lansdowne, 18 December 1890, quoted in Basu. p. 87

- Basu, pp. 26–27

- Anand, p. 13

- Basu, p. 33

- Quoted in Anand, p. 15

- Quoted in Basu, p. 38

- Quoted in Basu, p. 43; Hibbert, p. 446 and Longford, p. 502

- Quoted in Basu, p. 44

- Basu, p. 48

- Basu, p. 57

- Basu, p. 49

- Quoted in Basu, p. 60

- Marina Warner's Queen Victoria's Sketchbook, quoted in "Abdul Karim" Archived 6 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. PBS. Retrieved on 15 April 2011

- Basu, pp. 64–65

- Basu, p. 64

- "Queen Victoria's Journals". RA VIC/MAIN/QVJ (W). Royal Archives. 11 August 1888. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- Basu, p. 65; Longford, p. 536

- Anand, p. 16

- Basu, p. 174

- Anand, p. 15

- Queen Victoria to the Duchess of Connaught, 3 November 1888, quoted in Basu, p. 65

- Victoria to Sir Theodore Martin, 20 November 1888, quoted in Basu, p. 65

- Nelson, p. 82

- Anand, p. 18

- Basu, pp. 68–69

- Victoria herself acknowledged that "he is a very irascible man, with a violent temper and a total want of tact, and his own enemy, but v. kind-hearted and hospitable, a very good official, and a first-rate physician", to which Lansdowne replied, "Your Majesty has summed up that gentleman's strong and weak points in language which exactly meets the case." (Quoted in Basu, p. 88)

- Anand, pp. 18–19; Basu, pp. 70–71

- Waller, p. 441

- Basu, p. 71; Hibbert, p. 448

- Erickson, Carolly (2002) Her Little Majesty, New York: Simon and Schuster, p. 241. ISBN 0-7432-3657-2. Paragraph break omitted after third sentence.

- Basu, pp. 70–71

- Victoria to Reid, 13 May 1889, quoted in Basu, p. 70

- Anand, pp. 20–21; Basu, pp. 71–72

- Basu, p. 72

- Basu, pp. 73, 109–110

- Basu, p. 74

- Basu, p. 75

- Basu, p. 76

- Quoted in Anand, p. 22 and Basu, p. 75

- Queen Victoria to Victoria, Princess Royal, 17 May 1890, quoted in Basu, p. 77

- Quoted in Basu, p. 77

- This Sceptered Isle: Part 66, "Queen Victoria and Abdul Karim" BBC Radio 4. Retrieved on 15 April 2011.

- Basu, p. 78

- Basu, pp. 79–82

- Basu, p. 83

- Anand, p. 33; Basu, p. 86

- Basu, p. 85

- Basu, pp. 86–87

- Basu, p. 100

- Basu, pp. 102–103

- Lansdowne to Victoria, December 1893, quoted in Basu, p. 111

- Queen Victoria to Victoria, Princess Royal, 9 December 1893, quoted in Anand, p. 45

- Basu, pp. 104–105

- Basu, p. 107

- Basu, pp. 106, 108–109

- Mallet, Victor (ed., 1968) Life With Queen Victoria: Marie Mallet's Letters From Court 1887–1901, London: John Murray, p. 96, quoted in Basu, p. 141

- Basu, p. 129; Hibbert, p. 447; Longford, p. 535

- Basu, pp. 59–60, 66, 81, 100, 103

- Basu, p. 104

- Birmingham Daily Post, 24 March 1893, quoted in Basu, p. 104

- e.g. Basu, p. 129

- e.g. Basu, p. 109

- Basu, p. 114; Hibbert, p. 450; Nelson, p. 83

- Basu, p. 115

- Basu, p. 116

- Basu, p. 117; Hibbert, p. 449; Longford, p. 536

- Ponsonby, Frederick (1951) Recollections of Three Reigns, London: Odhams Press, p. 12, quoted in Basu, p. 120 and Hibbert, p. 449

- Basu, pp. 119–120; Longford, p. 537

- Basu, p. 121

- Quoted in Anand, p. 54; Basu, p. 125 and Hibbert, p. 451

- Basu, p. 125

- Basu, pp. 123–124; Hibbert, p. 448; Longford, pp. 535, 537

- Basu, pp. 148–151; Longford, p. 540

- Basu, pp. 127–128

- "No. 26628". The London Gazette. 25 May 1895. p. 3080.

- Basu, p. 130

- Hamilton to Elgin, 21 February 1896, quoted in Basu, p. 137; Hibbert, p. 449 and Longford, p. 538

- Anand, pp. 71–74; Basu, p. 138

- Anand, pp. 71–74

- Basu, p. 140

- Basu, p. 108

- Basu, p. 141; Erickson, p. 246; Hibbert, p. 451

- Basu, pp. 141–142; Hibbert, p. 451

- Letter from Frederick Ponsonby to Henry Babington Smith, 27 April 1897, quoted in Anand, pp. 76–77, Basu, p. 148 and Longford, p. 539

- Basu, p. 143; Longford, pp. 540–541

- Basu, pp. 141–145; Hibbert, pp. 451–452

- Basu, p. 144

- Hamilton to Elgin, 30 April 1897, quoted in Basu, p. 149

- Basu, pp. 147, 151, 172

- Anand, p. 105

- Quoted in Basu, p. 150

- Basu, p. 162; Hibbert, p. 451

- Victoria to Karim, 12 February 1898, quoted in Anand, p. 96; Basu, p. 167 and Hibbert, p. 453

- Reid to Victoria, 23 September 1897, Basu, p. 161

- Reid's diary, 18 February 1898, quoted in Basu, p. 169 and Hibbert, p. 454

- Quoted in Anand, p. 101

- Anand, p. 111

- Basu, pp. 173, 192

- Reid's diary, 4 April 1897, quoted in Basu, pp. 145–146 and Nelson, p. 110

- Quoted in Basu, p. 161

- Basu, pp. 150–151

- Basu, p. 156

- "No. 27084". The London Gazette. 30 May 1899. p. 3427.

- Basu, pp. 178–179

- Basu, pp. 180–181

- Basu, p. 182; Hibbert, pp. 498; Rennell, p. 187

- Anand, p. 102

- Anand, p. 96; Basu, p. 185; Longford, pp. 541–542

- Quoted in Anand, p. 102

- Quoted in Anand, pp. 103–104 and Basu, p. 192

- Basu, p. 193

- Basu, p. 198

- Basu, p. 19

- Basu, pp. 197–199

- Basu, pp. 200–201

- Basu, p. 202

- Leach, Ben (26 February 2011). "The lost diary of Queen Victoria's final companion". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Basu, p. 206

- Longford, p. 535

- Longford, p. 536

- Visram, Rozina (2004). "Karim, Abdul (1862/3–1909)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/42022. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Lutyens, Mary (1961) Lady Lytton's Court Diary 1895–1899, London: Rupert Hart-Davis, p. 42

- Longford, p. 502

- e.g. Longford, p. 541; Plumb, p. 281

- Victoria to Salisbury, 17 July 1897, quoted in Longford, p. 540

- Al-Khadi, Amrou (16 September 2017). "Victoria and Abdul is another dangerous example of British filmmakers whitewashing colonialism". The Independent. Archived from the original on 17 September 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

Bibliography

- Anand, Sushila (1996) Indian Sahib: Queen Victoria's Dear Abdul, London: Gerald Duckworth & Co., ISBN 0-7156-2718-X

- Basu, Shrabani (2010) Victoria and Abdul: The True Story of the Queen's Closest Confidant, Stroud, Gloucestershire: The History Press, ISBN 978-0-7524-5364-4

- Hibbert, Christopher (2000) Queen Victoria: A Personal History, London: HarperCollins, ISBN 0-00-638843-4

- Longford, Elizabeth (1964) Victoria R.I., London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 0-297-17001-5

- Nelson, Michael (2007) Queen Victoria and the Discovery of the Riviera, London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks, ISBN 978-1-84511-345-2

- Plumb, J. H. (1977) Royal Heritage: The Story of Britain's Royal Builders and Collectors, London: BBC, ISBN 0-563-17082-4

- Rennell, Tony (2000) Last Days of Glory: The Death of Queen Victoria, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-30286-X

- Waller, Maureen (2006) Sovereign Ladies: The Six Reigning Queens of England, New York: St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0-312-33801-5

External links

- Queen Victoria's Last Love, Channel 4 2012 documentary narrated by Geoffrey Palmer, about Queen Victoria (played by Veronica Clifford) and the Munshi (played by Kushal Pal Singh)

- Queen Victoria's Last Love (2012), details of the above documentary at the Internet Movie Database

- Queen Victoria and Abdul: Diaries reveal secrets, BBC News, 14 March 2011

- Abdul Karim, who taught Queen Victoria Hindustani, British Library, Asians in Britain collection

- Entries mentioning Abdul Karim in Queen Victoria's Journals, hosted by the Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford