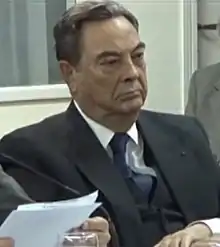

Abel Posse

Abel Parentini Posse (7 January 1934 – 14 April 2023) was an Argentine novelist, essayist, poet, career diplomat, and politician.

Abel Posse | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 January 1934 |

| Died | 14 April 2023 |

| Occupation | Diplomat, writer, essayist |

| Awards |

|

| Website | http://www.abelposse.com |

Posse was the author of fourteen novels, seven collections of essays, an extensive journalistic work, together with a series of short stories and poems. His narrative fiction has received several distinguished awards.

In November 2012 he became a numbered member of the Argentine Academy of Letters.

Posse carried out uninterrupted diplomatic duties for the Argentine Foreign Service from 1966 until 2004.

Posse was a regular contributor to the liberal-conservative daily La Nación in Buenos Aires, as well as other Argentine dailies (Perfil, La Gaceta de Tucumán) and Spanish papers (ABC, El Mundo and El País). He was also editor in-chief of the Revista Argentina de Estudios Estratégicos (Argentine Journal of Strategic Studies). His journalistic publications include some 400 articles, many of which have been published in his collection of socio-political essays, such as, Argentina, el gran viraje (2000), El eclipse argentino.

Childhood and youth

Abel Parentini Posse was born on 7 January 1934, in the Argentine city of Córdoba where he only lived the first two years of his life.[1] Two years after birth the family moved to the capital city of Buenos Aires due to his father's work commitments. His mother, Elba Alicia Posse, belonged to the Creole-landed oligarchy of Galician descent who held vast sugar mill estates in the North West province of Tucuman. Amongst the influential members of the Posse clan in the 19th century, the liberal Julio Argentino Roca stands out, twice as president of the republic from 1880 to 1886 and also from 1898 to 1904 (3). Posse fictionalized 19th century Tucuman in his novel El inquietante día de la vida (2001), where two distant family relatives are the protagonists; his maternal great-grandfather, Felipe Segundo Posse, and Julio Victor Posse, patron of the arts in the sugar-producing province until the 1940s.

The novelist's father, Ernesto Parentini, a porteño of Italian parents, was one of the founders of Artistas Argentinos Asociados and was the producer of the legendary feature film La guerra gaucha (1942), based on the text by the poet Leopoldo Lugones. The young Abel Posse grew up in the Argentine capital near Rivadavia street, and given his father's profession was exposed to the artistic and cultural milieu this most sophisticated of the South American capitals had to offer. The “Queen of the River Plate”, as Buenos Aires came to be known, fascinated the young man, (4) and his memories are evoked in his novel Los demonios ocultos (1987). He was able to mingle with the glamorous stars of Argentine show business, like Chas de Cruz, Pierina Dealessi, Ulises Petit de Murat, Muñoz Azpiri, the writer of radio plays which were performed by Eva Duarte (de Perón), as well as the tango composers Aníbal Troilo and Homero Manzi. Such were the family connections to show business that one of his aunts, Esmeralda Leiva de Heredia, better known as “La Jardín”, was an actress friend of Eva Duarte. (5) Growing up in this environment enabled him to obtain an almost encyclopaedic knowledge of the tango repertoire and its culture, (6) which imbues his novel La reina del Plata (1988).

The imagination of the young Posse was awakened and nurtured by the father's personal library. (7) When he was eight he wrote and illustrated little books he would sell to his grandmother, who lived in the same apartment complex. (8) He undertook his primary education at the Colegio La Salle (9) and his secondary education between 1946 and 1952 at the prestigious Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires. (10) During these formative years in his intellectual development he began close friendships with people who would usher him into Buenos Aires literary circles, such as Rogelio Bazán, the translator of Georg Trakl. Posse would later dedicate a poetic tribute to the German bard.

Amongst his teachers, the orientalist philosopher Vicente Fatone stands out as an influential figure, awakening in Posse an interest in esoteric philosophy which is evident in several of his novels, especially in Los demonios ocultos and El viajero de Agartha. In 1943, at age 13, Posse launched himself into his first literary project (never completed), a novel set in imperial Rome. (11)

The fiesta of the “Queen of the River Plate”

Posse studied at the Law Faculty in Buenos Aires until 1958. Apart from his studies “lectured by fascist-Peronist professors” (12) who bored him, he lived the “nightlife” fiesta of Buenos Aires, a city which in those days was home to the most important publishing houses in the Spanish-speaking world and also to exiled writers and intellectuals of the Spanish Civil War. According to Posse, his nighttime meetings and conversations in Buenos Aires cafés allowed him to deepen his knowledge of Russian and French literature, German philosophy and Oriental spiritualism. In this rich bohemian environment he met Jorge Luis Borges, Eduardo Mallea, Ezequiel Martínez Estrada, Ricardo Molinari, Manuel Mujica Lainez, Ramón Gomez de la Serna and Rafael Alberti (13). He became close friends with the poets Conrado Nalé Roxlo and Carlos Mastronardi, as well as Borges, who opened the doors for him of the SADE and who would later help him to publish his first short stories and poems in the daily El Mundo. In those years Posse became attracted to Peronist ideas. Although he had been born into an anti-Peronist family, the huge public demonstration of 17 October 1945 had left a lasting impression (14), as had the strength of Evita and her ability to bring life into the movement, together with the open public grieving aroused by her funeral in 1952. These years of university life and above all of the nightlife in Buenos Aires are depicted by Posse as a true “golden age” which he recreates in certain passages of La reina del Plata (1988) and La pasión segun Eva (1994), a fictional biography which conveys the last days of Eva Perón. After having undertaken his military service in 1955, during the anti-Peronist Revolución Libertadora, Posse completed his university studies in 1958. That same year, he wrote a screenplay, “La cumparsa” (The Troupe), which was given an award by the National Institute of Cinematography; set in Patagonia, the troupe is composed of a group of sheep shearers who turn out to be a veritable court of miracles. (15)

Voyage to Europe

After graduating, Posse decided to travel to Europe. Thanks to a university scholarship, he undertook doctoral studies in Political Sciences at La Sorbonne in Paris. A few months prior to his travels, he published his first poem, “Invocación al fantasma de mi infancia muerta”, in the literary supplement of El Mundo (16). While in Europe, he crossed the Alps on a motorbike in order to visit his sister in Italy. In this period he deepened his knowledge of the poetry of Hölderlin, Rilke and Trakl (17). During his stay in Paris, he listened to Sartre, he had as professors eminent French political scientists of the time (Duverger, Hauriou, Rivarol) and also met Pablo Neruda (18). During his stay in the “City of Light” he fell in love with a German student, Wiebke Sabine Langenheim, his future wife, who would play an important role in his literary formation, guiding his readings of German literature and philosophy which infuse his works. In 1961 he spent two semesters in Tübingen, Germany, the home of Hölderlin. That same year, his poem, “En la tumba de Georg Trakl”, the first ever text signed as Abel Posse, was awarded the Rene Bastianini prize of the SADE in Buenos Aires. During his stay in Tübingen, he read Hölderlin, Nietzsche and Heidegger (19). It was also here that he began writing his first novel, Los bogavantes, which he would finish in 1967.

From Buenos Aires to the Foreign Service

Posse returned to Buenos Aires in 1962. After a competitive selection process, he taught as an assistant in constitutional law under professor Carlos Fayt at the University of Buenos Aires. With little enthusiasm, he also began to work as a lawyer. Sabine traveled to Argentina and a while later they were married. In 1965 he was admitted to the Argentine Foreign Service after a public selection process (20). Until 2004 he would live most of his life abroad, as such most of his works were written outside of Argentina, although he always defended his Argentine identity, his literary production was well served by Ricardo Güiraldes’ adage, “distance reveals” (21).

Moscow (1966–1969)

Abel Posse's only son, Ivan, was born in Moscow in January 1967. At this time in the Russian capital, he also finished writing his first novel, Los bogavantes, set in Paris and Seville, centered on a trio of characters, two of whom are students and one a Foreign Service employee, embodying the ideological tensions of the early 1960s. This neo-realist novel played an important part in his literary career. Under the pseudonym of Arnaut Daniel, Posse submitted it to the 1968 Planeta Prize. It featured among the four finalists, and although it had been virtually declared the winner by the judges José Manuel de Lara and Baltasar Porcel, under Francoist pressure the judges had to overturn their decision, due to some charged erotic scenes, above all because of its critical and ironical references to the regime's military. Once it had been published in 1970 by Editorial Brújula in Argentina, thanks to the support of Ernesto Sabato and Posse's father, and after it received the Sash of Honour of the SADE, Los bogavantes was later published in Barcelona in 1975 where it was the object of Francoist censorship. All 5000 copies were purged of two pages that ridiculed the masculinity of army officers. This singular publishing episode (22) brought him under the attention of those who were the leading literary publishers of the time, Carlos Barral and Carmen Balcells; the latter would become his literary agent.

Lima (1969–1971)

Abel Posse was posted to Peru in 1969 and appointed cultural secretary of the embassy in Lima. For him Peru represented the discovery of Inca culture, the “revelation of the Americas” (23) which compelled him to identify himself with his Creole roots of North-Western Argentina (24). A visit to Machu Picchu inspired a long poem of 240 verses, Celebración de Machu Picchu, which he wrote in Cuzco in 1970 and published much later in Venice in 1977. Also in 1970, he wrote his most ambitious poetical piece, Celebración del desamparo, which was amongst the finalists of the Maldoror Poetry Prize although Posse decided against publishing it. In those years he read José María Arguedas and the great Cuban stylists: Alejo Carpentier, Lezama Lima and Severo Sarduy. He also researched the life of Argentina's national independence hero, General José de San Martín, and in 1971 was admitted to the Instituto Sanmartiniano de Lima. In Peru he also wrote his second novel, La boca del tigre (1971), inspired by his personal experiences in the Soviet Union. This novel, clearly influenced by Ernesto Sabato's neo-realist style of fiction, helped the author to articulate his distrust of the overbearing ideologies of the time, in order to criticize the exercise of power in the contemporary world and to reflect on the place of the individual in that historical juncture. This thematic concern foreshadowed the ideas about history in his later novel Daimon. La boca del tigre, which received the third National Prize of Argentine Literature, hints at his initial musings on the notion of Americanness (americanidad). (25) The influence that the Argentine philosopher and anthropologist Rodolfo Günther Kusch would have on Posse's fiction and indeed his own worldview after his encounter with him and his readings of La seducción de la babarie (1953) and América profunda (1962). Consequently, Kusch's thought on the fundamental ontological and cultural antagonism between the West's homo faber with the Americano “man of being” and the symbiotic relationship of Amerindians with the Cosmos (“the Open”) was to become a leitmotif in Posse's work, and particularly in his “Trilogy of the Discovery of America”.

Venice (1973–1979)

Posse was named Consul General for Venice in 1973, where he lived for 6 years. It was here that he wrote Daimon (1978), between October 1973 and August 1977, the novel which began the “Trilogy of the Discovery of America”. This novel has as its protagonist a fictional avatar of the Spanish conquistador Lope de Aguirre (1510–1561). In this text, the conqueror, known for his cruelty which is depicted by chroniclers as the archetypal madman and traitor, raises from his ashes eleven years after his death together with the ghosts of his Marañones. Thus begins the “Jornada de América”, through four centuries of painful Latin American history, on which he casts a disillusioned gaze, by seeing it as an “Eternal-Return-of-the-Same”; that is the eternal annihilation of man's liberty against which Lope de Aguirre's rebelliousness is powerless to arrest. This fruitless trans-historical rebellion drives him to an ambiguous death in the mid-1970s in Latin America, a condition that bears a resemblance to the death of Ernesto Che Guevara's revolutionary venture in Bolivia. Several scenes of torture suffered by the protagonist clearly resemble the atrocities committed by the Argentine military during the country's last military dictatorship. (26) This novel constitutes a milestone in Posse's poetics, as it is enthused with Rabelaisian elements in a baroque style, by continually resorting to the use of humour and ambiguity, to parody, intertextuality, anachronism, the grotesque, and continuous paratextual dialogue with the reader, characteristics which would reach their highest intensity in the subsequent novel, The dogs of paradise (1983). Daimon was shortlisted for the prestigious Romulo Gallegos Prize in 1982.

The Venetian sojourn was where he received the recognition of his peers; he was visited by friends such as Ernesto Sabato, Carlos Barral, Manuel Scorza, Victor Massuh, Antonio Requeni, Manuel Mujica Lainez, Jorge Luis Borges, Antonio Di Benedetto and Juan Rulfo. (27) He also met in Venice, Alejo Carpentier, who was writing his Concierto barroco (1974), as well as Italo Calvino, Alberto Moravia and Giorgio Bassani. During his years in Venice, Posse reflected on the Heideggerian concept of “the Open” (Das Offene) and Kusch's ideas concerning ‘being’. (29) In 1973 he visited the German philosopher Martin Heidegger (30), and in 1979 together with his wife Sabine published a Spanish translation of Der feldweg. (31) After a brief trip to Buenos Aires in 1975, and on his return to Venice, he wrote between April and June of the same year a dark novel reflecting the murderous political violence being played out in Argentina at the time, titled Momento de morir, but which he did not publish until 1979. Its protagonist, Medardo Rabagliatti, a rather mediocre and irresolute suburban solicitor, is witness to the unfolding armed violence perpetrated by groups of youngsters depicted as fanatics and a sadistic military. Against all odds, the story's denouement sees the vacillating Medardo kill the murderous military leader responsible for the repression and later oversee the re-establishment of democratic political institutions in the country. The historical reading proposed by the author (various characters are clearly fictional avatars of Mario Firmenich and Hector J. Campora) condemns without a doubt the ERP (Ejercito Revolucionario del Pueblo), the Monotoneros and the military repression, thus underlining the “thesis of two evils”; a thesis the author holds in the prologue he added to the 1997 edition. (32)

Paris (1981–1985)

In 1981 Posse was appointed director of the Argentine Cultural Centre in Paris. It was there where he wrote The dogs of paradise (1983), second part of his “Trilogy”, with Christopher Columbus as its protagonist, and for which he was awarded the 1987 Rómulo Gallegos Prize. This novel, translated into many languages, confirmed Posse, according to many literary scholars, as one of the leading exponents of Latin America's “New Historical Novel”. As in Daimon, the novel questions the validity of the official historiography of the conquest of the Americas, undermines the laws governing space and time, and anachronism is systematic, as is intertextuality, the pastiche, parody, while the work harbours, like Daimon, a profound reflection on the Latin American condition and its identity. The dogs of paradise explores the motivations of the Catholic Monarchs and Columbus, as well as the aftermath of the clash of cultures triggers by the arrival of the Spaniards through the dialogical testimony of the defeated. Between 1982 and 1985 Posse edited a bilingual collection (Spanish and French) of 15 Argentine poets titled Nadir, which included: Leopoldo Lugones, Enrique Molina, Héctor Antonio Murena, Juan L. Ortiza, Ricardo Molinari, Conrado Nalé Roxlo, Baldomero Fernandez Moreno, Alejandra Pizarnik, Oliverio Girondo, Manuel J. Castilla, Alberto Girri, Raul G. Aguirre, Juan Rodolfo Wilcock, Ezequiel Martínez Estrada and Leopoldo Marechal. This project was carried out with the assistance of Argentine and French poets, academics and translators. The volumes were gifted and distributed to French libraries and universities, with the aim of increasing interest in these works internationally. The project was no doubt inspired by Roger Caillois who, with his collection La Croix du Sud, made a major contribution to the international recognition of Jorge Luis Borges’ work. (34) In January 1983 at age 15, Ivan, Posse's only son committed suicide at the family's apartment in Paris, a tragedy which the author would chronicle many years later in Cuando muere el hijo (2009), an autobiographical account presented as a “real chronicle”. When The dogs of paradise appeared in bookshops he announced the forthcoming publication of the third sequel of the “Trilogy”, titled Sobre las misiones jesuíticas, to be set in the Jesuit missions of Paraguay. (35) While its appearance was announced in 1986, with a different title, Los heraldos negros, it is as yet unpublished. (36) In November 1983, alongside the Paris Autumn Festival, Posse organised with Claudio Segovia a tango festival called Tango argentin, where Roberto Goyeneche participated and which was destined, as it were in his own words: “to bring to life the real tango, the primitive tango of the origins” as against the “tango for export” of Astor Piazzolla. (37)

Israel (1985–1988)

After the death of his son, Posse could no longer live in Paris and he was appointed Plenipotentiary Minister at the Argentine embassy in Tel-Aviv. He returned to writing there, and wrote three novels, quite different to his previous ones. He wrote two novels on Nazism, Los demonios ocultos (1987) and El viajero de Agartha (1989). Los demonios ocultos was a literary project Posse had begun much earlier in 1971, after having met several Nazis in Buenos Aires during his university days. The protagonist of the novels, cast in a neorealist style, is a young Argentine, Alberto Lorca, who goes in search of his father, Walther Werner, a German scientist who specialized in Oriental esoterism, who was sent by the Third Reich on a mission to Central Asia. The plot takes place in two temporal spaces, the Second World War and the Argentina of the last military dictatorship. El viajero de Agartha (1989, Premio Internacional Diana-Novedades, Mexico) is a true adventure espionage novel. Walter Werner as protagonist narrates the story in a diary recovered by his son, which recounts his mission in Tibet in his search for the mythical city of Agartha. The third novel, La reina del Plata (1988), as the title indicates is a homage to the Argentine capital and the period of splendor it once knew. The novel takes place in a futuristic Buenos Aires, whose society is polarized between “Insiders” and “Outsiders”, where the “Outsider” Guillermo Aguirre ruminates on his own identity. The plot is narrated in fragments comprising ninety short chapters, while the action takes place in the typically Buenos Aires atmosphere of cafes and streets inhabited by the tango, the deep musical expression of the port city, where its characters muse about the past and present of the country.

Prague (1990–1996)

In 1990 Posse was promoted to Ambassador by President Carlos S. Menem and was posted to Prague for six years. His stay in the Czech capital was quite productive. Here he composed his literary essay Biblioteca essential which he published in 1991, where he proposes the most important 101 works of universal literature and his own canon of the literature of the River Plate. Posse also wrote in the Czech capital El largo atardecer del caminante, the novel which closes the “Trilogy of the Discovery of America”, and which was crowned with the Premio Internacional Extremadura-America V Centenario 1992, where 180 novels had entered. In this work, the baroque style of Daimon and The dogs of paradise give way to a more somber and reflective style. The protagonist in this work is the conqueror Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca (1490–1558), who lives the last years of his life in a humble abode in Seville, where he reminisces about his ‘true’ American adventure through an autobiographical and sincere retelling of his exploits by filling in the blanks and the silences left by his chronicles titled Castaways and Commentaries. Posse's Cabeza de Vaca assumes his americanidad, his hybrid identity, by announcing his maxim, “only faith can cure, only kindness heals” as a way the conquest should have taken place. This introspective and autobiographical style is continued in his next work, La pasión según Eva (1994). This is a biographical novel (fictionalised biography) with a polyphonic text which sees an ailing Eva Perón living the last nine months of her life while casting a retrospective gaze over her life. At the same time, Posse collects and recovers the testimony of people who knew her, illustrating and readjusting Eva's own account. Although the text has a clear empathy with its subject, the novel's stated aim is to provide a deeper understanding of this powerful woman than given by previous biographies, taking her life out of the ideological straitjacket and transforming it into a destined life.

Lima (1998–2000)

During his posting as ambassador to Lima, Peru, Posse wrote another biographical novel, Los cuadernos de Praga (1998), which also has as its protagonist another memorable 20th-century Argentine, Ernesto ‘Che” Guevara Lynch. As with several of his earlier novels, the author was inspired by personal experience; Posse was informed during his stay in Prague that Che Guevara lived undercover in the city for almost a year after his defeat in the Congo. Like in La pasión según Eva, the motive of the personal diary is the trigger for the autobiographical account, an account that converses with the research the author has carried out. Similarly to the previous novel, the objective of the author is not to simply recount the life of the historical person, but based on “solid foundations”, rescue his destiny in order to give an account of his life beyond the ideological. (38) On his return to Latin America after his European postings Posse increased his journalistic opinion pieces in El Excelsior (Mexico), El Nacional (Caracas), ABC and El Mundo (Madrid), Linea and La Nación (Buenos Aires). Posse arrived in Peru when there was still a tense relationship with Ecuador over the war of El Condor, and in the aftermath of the kidnapping of hostages at the Japanese embassy by the MRTA (1997). Posse spoke highly of the Alberto Fujimori's war against the MRTA at the same time he expressed his opposition to the trials by Baltasar Garzón against Augusto Pinochet and the International Human Rights Court, measures which he attributed to meddling into the internal affairs of Latin American countries. His opinion pieces also underscored the role Argentina could play in the consolidation of MERCOSUR and highlighted the natural resources of the country for the benefit of the next millennium, by appealing to the patriotism of its citizens and calling on them to imitate the example of Julio Argentino Roca, Hipölito Yrigoyen and Juan Domingo Perón. Many of these articles were brought together in the first collection of political essays he published in Argentina, el gran viraje (2000). His return to Peru renewed his interest in the national hero, Jose de San Martin, which inspired the short story “Paz en guerra” (2000).

Copenhagen (2001–2002)

In 2001 Posse published El inquietante día de la vida, which received the Literary Prize of the Argentine Academy of Letters for the period 1998–2001. The protagonist is Felipe Segundo Posse, based on a real-life ancestor of his who was heir to a vast estate of sugar mills in Tucuman province in the late 19th century. The story begins when he is diagnosed with tuberculosis and decides to abandon his family by traveling to Buenos Aires and then on to Egypt in search of the poet Rimbaud. The novel also fictionalizes historical characters like Domingo F. Sarmiento, Julio A. Roca and Nicolás Avellaneda while celebrating Argentina's development at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries.

Madrid (2002–2004)

After a brief posting at UNESCO in Paris, Posse was appointed by President Duhalde Argentine ambassador to Spain. This was a hugely important posting, particularly due to the aftermath of the 2001 Argentine financial collapse, as this country was the main destination of Argentine migrants of Spanish descent. At the time Posse witnessed the deadly terrorist attacks in the Spanish capital on 11 March 2004. Deeply concerned by the crisis facing Argentina, Posse increased his opinion pieces in La Nación, defending regional integration, national sovereignty, and appealing to national reconstruction by evoking the memory of national figures such as Sarmiento and Evita. In 2003 he published another collection of political articles, El eclipse argentino. De la enfermedad colectiva al renacimiento, a work which attempts to outlay a blueprint for a national project. Once Néstor Kirchner assumed power, several media outlets pronounced Posse as the preferred candidate as foreign affairs minister, given his diplomatic experience, his age and his key posting in Spain. The journalist and former Montonero militant Miguel Bonasso published an opinion piece and participated in a TV program where he appealed to the president to put aside Posse's candidature, whom he accused of having a benevolent attitude toward the previous military dictatorship for not having abandoned his diplomatic duties, and for his support of the Fujimori regime. (39) The president appointed Rafael Bielsa as foreign affairs minister, while Posse continued his appointment at the embassy in Madrid until his retirement in 2004 when he returned to Argentina.

Buenos Aires (2004–2023)

After his retirement, Posse's commitment to the anti-Kirchner opposition increased. In very critical and controversial newspaper columns he linked the president and his supporters to extreme left-wing militant movements of the 1970s, and he also opposed the restart of trials against the military, and the government's policy of collective memory which he labeled as incomplete. He increased his round of conferences on the state of the nation, and he supported the presidential candidacy of Eduardo Duhalde in 2007, when he was also a senate candidate for the City of Buenos Aires in Roberto Lavagna's ticket. In 2005 he published En letra grande, a collection of literary essays and reflections on intellectuals close to him and who he considered as influential. He also published in 2006 a series of political essays under the title, La santa locura de los argentinos, which was a best-seller, where he attempts to map the Argentine question by focusing his analysis from colonial times to the last century in order to make a call for a citizen led national consensus. In October 2009 he published Cuando muere el hijo, a testimonial novel where the narrators A and S experience the suicide of Ivan, and they try to come to terms with their son's decision. Later they undertake a journey of internal and external initiation when they travel from Paris to Tel-Aviv, and make a stop-over in Miletus, the city of the pre-Socratic philosopher Anaximander of Miletus. Toward the end of 2009 Posse accepted the appointment of Minister of Education of the City of Buenos Aires offered by Mauricio Macri, which had been left vacant by Mariano Narodowski. Posse took office a day after having published a controversial article in the daily La Nación, titled “Criminality and cowardice”, where he declared that rock music dumbed down the young, and he judged as ineffective law and order measures of the President, while demanding stronger measures against criminals. He also rejected the reopening of trials against members of the military regime and reiterated his accusations against Kirchner for his ideological proximity to the 1970s militant left-wing movements. (40) His appointment and this opinion piece triggered a wave of protests by unions and students, from the rock-music scene and web-based social networks, to sections of the media, such as Página 12, who accused Posse of having had close ties with previous dictatorship and of asserting that most of his diplomatic career had taken place during the last military junta, which had been first aired by Miguel Bonasso in his 2003 column referred to earlier. In fact, one of the most notorious henchmen of the military who coincidentally was on trial during those days, Benjamin Menendez, paraphrased a few sentences from Posse's article which was taken up by the media tarnishing Posse's image even further. Given such circumstances, Posse resigned 11 days into his new posting. In 2011 he published Noche de lobos, based on the written account of a Montonero female leader who had been held captive and tortured at the ESMA (Navy School of Mechanics) and who had fallen in love with her torturer. This work delves into the conflicts between the urban guerrillas and the military, and both are portrayed as the protagonists of murderous acts of savagery. It recounts the acts of torture suffered by this woman in this clandestine detention centre, and how she falls prey to the so-called “Stockholm syndrome”, where tortured and torturer fall in love with each other. This novel also has an autobiographical focus, as it reveals how this female guerrilla fighter while she was a captive at the hands of the military had given her typed account to Posse of her story in the early 1980s while he was in the Argentine embassy in Paris. (42) Since his resignation as Minister of Education of Buenos Aires, Abel Posse continued to live in this city, where he gave conferences, especially on Sarmiento's education legacy, and where he published frequently in Perfil and La Nación. He remained critical of the Kirchner policies and concerned about the future of the country. Since November 2012, Abel Posse was an elected numbered member of the Argentine Academy of Letters (43), having taken the place of the late Rafael Obligado. In May 2014 he became an elected numbered member of the National Academy of Education taking the numbered chair Bartolome Mitre.

Abel Posse died on 14 April 2023, at the age of 89.[2]

List of works

Novels

- Los bogavantes (1970)

- La boca del tigre (1971)

- Daimón (1978) (Translated from the Spanish by Sarah Arvio. Atheneum, Macmillan, New York, 1992)

- Momento de morir (1979)

- Los perros del paraíso (1983); The dogs of Paradise (Translated from the Spanish by Margaret Sayers Peden. Atheneum, Macmillan, New York, 1989)

- Los demonios ocultos (1987)

- La reina del Plata (1988)

- El viajero de Agartha (1989)

- El largo atardecer del caminante (1992)

- La pasión según Eva (1994)

- Los cuadernos de Praga (1998)

- El inquietante día de la vida (2001)

- Cuando muere el hijo (2009)

- Noche de lobos (2011)

- Vivir Venecia (2016, forthcoming)

Essays

- Biblioteca essential (1991)

- Argentina, el gran viraje (2000)

- El eclipse argentino. De la enfermedad colectiva al renacimiento (2003)

- En letra grande (2005)

- La santa locura de los argentinos (2006)

- Sobrevivir Argentina (2014)

- Réquiem para la política. ¿O renacimiento? (2015)

Poetry

- “Invocación al fantasma de mi infancia muerta”, El Mundo, Buenos Aires, 13/03/1959.

- “En la tumba de Georg Trakl”, Eco, Revista de la cultura de Occidente, Bogotá, n°25, 05/1962, p. 35-37.

- “Georg Trakl 1887-1914”, La Gaceta, San Miguel de Tucumán, 1/02/1987.

- Celebración del desamparo, 1970 (inédito).

- Celebración de Machu Pichu (1977)

Short stories

- “Cuando el águila desaparece”, La Nación, 17/08/1989.

- “Paz en guerra”, en Relatos por la paz, Amsterdam: Radio Nacional Holanda, 2000, p. 67-75

Translations

- Martín Heidegger, El sendero del campo, traducción de Sabine Langenheim y Abel Posse, Rosario: Editorial La Ventana, 1979, 58 p.

Bibliography

- Página oficial de Abel Posse: http://www.abelposse.com

- Sáinz de Medrano, Luis (coord.), Abel Posse. Semana de author, AECI: Madrid, 1997.

- Abel Posse en la Audiovdeoteca de Buenos Aires: https://web.archive.org/web/20121015142732/http://www.audiovideotecaba.gov.ar/areas/com_social/audiovideoteca/literatura/posse_bio_es.php

- Aínsa, Fernando, La nueva novela histórica latinoamericana, México: Plural, 1996, p. 82-85.

- Aracil Varón, Beatriz, Abel Posse: de la crónica al mito de América, Cuadernos de América sin nombre n.º 9, Universidad de Alicante, 2004.

- Esposto, Roberto, Peregrinaje a los Orígenes. “Civilización y barbarie” en las novelas de Abel Posse, New México: Research University Press, 2005.

- Esposto, Roberto, Abel Posse. Senderos de un caminante solitario. Buenos Aires: Biblos, 2013.

- Filer, Malva, «La visión de América en la Obra de Abel Posse», en Spiller, Roland (Ed.), La novela Argentina de los años 80, Lateinamerika Studien, Erlangen, vol. 29, 1991, p. 99-117.

- Lojo, María Rosa, «Poéticas del viaje en la Argentina actual», en Kohut, Karl (Ed.), Literaturas del Río de la Plata hoy. De las utopías al desencanto, Madrid-Frankfurt, Iberoamericana-Vervuert, 1996, p. 135-143.

- Magras, Romain, «L’intellectuel face à la célébration du (bi)centenaire de la Nation argentine. Regards croisés sur les figures de Leopoldo Lugones et Abel Posse», en Regards sur deux siècles d’indépendance: significations du bicentenaire en Amérique Latine, Cahiers ALHIM, n.º 19, Université Paris 8, 2010, p. 205-220. http://alhim.revues.org/index3519.html

- Maturo, Graciela, «Interioridad e Historia en El largo atardecer del caminante de Abel Posse», en América: recomienzo de la Historia. La lectura auroral de la Historia en la novela hispanoamericana, Buenos Aires: Biblos, 2010, p. 87-100.

- Menton, Seymour, «La denuncia del poder. Los perros del paraíso», en La nueva novela histórica, México: FCE, 1993, p. 102-128.

- Pons, María Cristina, «El secreto de la historia y el regreso de la novela histórica», en Historia crítica de la literatura Argentina. La narración gana la partida, Buenos Aires, Emecé Editores, 2000, p. 97-116.

- Pulgarín Cuadrado, Amalia, «La reescritura de la historia: Los perros del paraíso de Abel Posse», en Metaficción historiográfica en la narrativa hispánica posmodernista, Madrid: Fundamentos, 1995, p. 57-106.

- Sáinz de Medrano, Luis, «Abel Posse, la búsqueda de lo absoluto», Anales de literatura hispanoamericana, n.º 21, Editorial Complutense, Madrid, 1992, p. 467-480.

- Sánchez Zamorano, J.A., Aguirre: la cólera de la historia. Aproximación a la «nueva novela latinoamericana» a través de la narrativa de Abel Posse, Universidad de Sevilla, 2002.

- Vega, Ana María, «Daimón, de Abel Posse. Un camino hacia la identidad latinoamericana», Los Andes, Mendoza, 9 de enero de 1990, p. 3-4.

- Waldegaray, Marta Inés, «La experiencia de la escritura en la novelística de Abel Posse», en Travaux et Documents, n.º 22, Université Paris 8, 2003, p. 117-132.

- Waldemer, Thomas, «Tyranny, writing and memory in Abel Posse’s Daimón», en Cincinnati Romance Review, Cincinnati, OH, 1997, n.º 16, p. 1-7.

References

- [Sobre sus recuerdos de este período, leer Antonio López Ortega, «Conversación con Abel Posse», Imagen, Caracas, 10/1987, n.º 100, p.3-6.

- Muere el escritor y diplomático argentino Abel Posse (in Spanish)