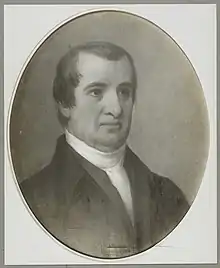

Abraham Clark

Abraham Clark (February 15, 1726 – September 15, 1794) was an American Founding Father, politician, and Revolutionary War figure.[1] Clark was a delegate for New Jersey to the Continental Congress where he signed the Declaration of Independence and later served in the United States House of Representatives in both the Second and Third United States Congress, from March 4, 1791, until his death in 1794.

Abraham Clark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from New Jersey's at-large district | |

| In office March 4, 1791 – September 15, 1794 | |

| Preceded by | Lambert Cadwalader |

| Succeeded by | Aaron Kitchell |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 15, 1726 Elizabethtown, Province of New Jersey, British America |

| Died | September 15, 1794 (aged 68) Rahway, New Jersey, US |

| Resting place | Rahway Cemetery, Rahway, New Jersey |

| Political party | Pro-Administration |

| Signature |  |

Early life

Clark was born in Elizabethtown in the Province of New Jersey. His father, Thomas Clark, realized that he had a natural grasp for math so he hired a tutor to teach Abraham surveying. While working as a surveyor, he taught himself law and went into practice. He became quite popular and became known as "the poor man's councilor" as he offered to defend poor men who could not afford a lawyer. He was a slaveholder.[2]

Clark married Sarah Hatfield circa 1749,[3] with whom he had 10 children.[4] While she raised the children on their farm, Clark was able to enter politics as a clerk of the Provincial Assembly. Later he became high sheriff of Essex County and in 1775 was elected to the Provincial Congress. He was a member of the Committee of Public Safety.

Political career

Early in 1776, the New Jersey delegation to the Continental Congress was opposed to independence from Great Britain. As the issue heated up, the state convention replaced all their delegates with those favoring the separation. Because Clark was highly vocal on his opinion that the colonies should have their independence, on June 21, 1776, they appointed him, along with John Hart, Francis Hopkinson, Richard Stockton, and John Witherspoon as new delegates.[5] They arrived in Philadelphia on June 28, 1776, and voted for the Declaration of Independence in early July.

Clark remained in the Continental Congress through 1778, when he was elected as Essex County's Member of the New Jersey Legislative Council. New Jersey returned him twice more, from 1780 to 1783 and from 1786 to 1788. Clark was one of New Jersey's three representatives at the aborted Annapolis Convention of 1786, along with William C. Houston and James Schureman.[6] In an October 12, 1804 letter to Noah Webster, James Madison recalled that Clark was the delegate who formally motioned for the Constitutional Convention, because New Jersey's instructions allowed for consideration of non-commercial matters.[7][8]

Clark, more than many of his contemporaries, was a proponent of democracy and the common man, supporting especially the societal roles of farmers and mechanics. Because of their emphasis on production, Clark saw these occupations as the lifeblood of a virtuous society, and he decried the creditor status of more elite men, usually lawyers, ministers, physicians, and merchants, as an aristocratic threat to the future of republican government.[9] Unlike many Founding Fathers who demanded deference to elected officials, Clark encouraged constituents to petition their representatives when they deemed change necessary.[10]

In May 1786, Clark, aided by thousands of petitions in the preceding months, pushed a pro-debtor paper money bill through the New Jersey legislature.[11] To garner support for the paper money bill and espouse his populist vision for New Jersey's future, Clark, under the pseudonym "A Fellow Citizen," published a forty-page pamphlet entitled The True Policy of New-Jersey, Defined; or, Our Great Strength led to Exertion, in the Improvement of Agriculture and Manufactures, by Altering the Mode of Taxation, and by the Emission of Money on Loan, in IX Sections in February 1786.[12]

Death and legacy

Clark retired before the state's Constitutional Convention in 1794. He died from sunstroke at his home. Clark Township in Union County, New Jersey, is named for him, as is Abraham Clark High School in Roselle, New Jersey. Clark is buried there at the Rahway Cemetery in Rahway, New Jersey.[13][14]

See also

Notes

- Bernstein, Richard B. (2011) [2009]. "Appendix: The Founding Fathers: A Partial List". The Founding Fathers Reconsidered. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199832576.

- Weil, Julie Zauzmer; Blanco, Adrian; Dominguez, Leo (January 20, 2022). "More than 1,700 congressmen once enslaved Black people. This is who they were, and how they shaped the nation". Washington Post. Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- Bogin, p. 163

- Bogin, p. 166

- Bogin, pp. 38-41

- Bogin, p.132.

- Bogin, pp. 132-133

- Brant, pp. 384-386.

- Bogin, pp. 32-37.

- Bogin, p. 37.

- Bogin, "New Jersey's True Policy: The Radical Republican Vision of Abraham Clark." William and Mary Quarterly, 3d ser., 35 (1978): p. 107.

- Bogin, pp. 160-161.

- Staff. "HOUSE OF ABRAHAM CLARK, A SIGNER, WILL BE REBUILT; Duplicate of Rahway Home to Memorialize Him and Two Sons as Revolutionary Patriots", The New York Times, February 6, 1927. Accessed September 21, 2015. "ABRAHAM CLARK, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, is to be honored by the erection of a memorial house in his home town, Rahway, N.J."

- Dodge, Andrew R. (2005) Biographical directory of the United States Congress 1774–2005, p. 824

References

- Bogin, Ruth, Abraham Clark and the Quest for Equality in the Revolutionary Era, 1774-1794. Rutherford, N.J.: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1982.

- Brant, Irving. James Madison: The Nationalist, 1780-1787, Indianapolis, Ind.: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1948.