Abul Fateh

Abul Fateh (Bengali: আবুল ফতেহ; 16 May 1924 – 4 December 2010)[1][2] was a Bangladeshi diplomat, statesman and Sufi[3] who was one of the founding fathers of South Asian diplomacy after the Second World War, having been the founder and inaugural Director of Pakistan's Foreign Service Academy[3] and subsequently becoming Bangladesh's first Foreign Secretary when it gained its independence in 1971. He was Bangladesh's senior-most diplomat both during the 'Liberation War' period of its Mujibnagar administration as well as in peacetime.

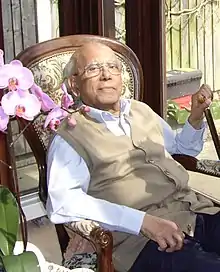

Abul Fateh | |

|---|---|

Abul Fateh as Calcutta High Commissioner in 1969 | |

| Born | 16 May 1924 |

| Died | 4 December 2010 (aged 86) London, England |

| Nationality | British Bangladeshi |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom, Bangladesh |

| Education | English literature |

| Alma mater | Ananda Mohan College University of Dhaka Graduate Institute of International Studies London School of Economics |

| Occupation(s) | Career diplomat and ambassador for Bangladesh and before that for Pakistan. |

| Known for | First Foreign Secretary of Bangladesh and its most senior diplomat and before that Founder and inaugural Director of Pakistan's Foreign Service of Pakistan. |

| Spouse |

Mahfuza Banu (m. 1956) |

| Children | 2 sons, including Eenasul Fateh |

A former Carnegie Fellow in International Peace and Rockefeller Foundation Scholar and Research Fellow,[3] he has been described as "soft-spoken and scholarly" and "a lesson for all diplomats".[4]

Exceptionally for a Bengali-born diplomat, he rose to the most senior ranks of public service in Pakistan.[4] Then at the time Bangladesh began seeking independence, he spectacularly defected and changed sides to support the fledgling country of Bangladesh – a major propaganda coup and morale boost for the cause of Bangladeshi liberation given his stature in Pakistan's hierarchy.[5][6] Abul Fateh was automatically the highest-ranked and most senior foreign service officer in the new country. His story was later documented in a National Geographic documentary, Running for Freedom.[1][7]

Following his death he was described by a former colleague and successor Foreign Secretary as "a great and brave freedom fighter" who was at the same time "remarkably reticent about his contributions", a "soft-spoken and scholarly diplomat" whose service to the Bangladeshi independence cause at a critical period was "invaluable" and "a lesson for all diplomats. His outstanding professional skill and deep sense of patriotism should be a shining example".[4] The Foreign Minister of Bangladesh Dipu Moni talked about his "contribution to self-right movements of people, country's independence struggle and managing assistance to war-ravaged country after independence."[8] She also cited his "outstanding career", stating that he would be "always remembered for his contribution to the country's liberation" war.[9]

Although rarely in the public eye, Abul Fateh was a distinguished figure in the history of post-Second World War, post-colonial diplomacy, a public servant who was a leading light behind the scenes within the Developing World and Non Aligned Conference, including the Commonwealth, with a significant tour of duty in Washington D.C. at the height of the Cold War. In the West too Abul Fateh came to be held in the highest regard, a rare joint U.S./U.K. intelligence assessment remarking in 1977 that he was: "very able, highly intelligent, moderate, easy to deal with, and well informed".

At the launch of his university's South Asia Centre in 2015, the President and Director of the London School of Economics Professor Craig Calhoun included Abul Fateh in a list of a dozen public figures of the 20th century who he felt represented "the greatest fruits" of the "close mutual relations between South Asia and the LSE".[10]

Biography

Early life and education

Abul Fateh was born in Kishoreganj on 16 May 1924 in a landowning family, to Abdul Gafur and his second wife Zohra Khatun. Abul Fateh was a middle child, in a large family of a dozen children who survived to adulthood, while two other siblings died young. His father Abdul Gafur had attended Presidency College, Calcutta, and was one of the first Muslim daroga (sheriffs) in British India. Abul Fateh's mother Zohra was the daughter of a local nobleman. Abul Fateh passed his matriculation exams from Ramkrishna High English School in Kishorganj in 1941. After passing his Intermediate exams from Ananda Mohan College in Mymensingh in 1943, he undertook higher studies in English Literature at Dhaka University (BA Honours in 1946 and MA in 1947) where he also excelled in sport, for a time captaining the cricket team and becoming the table tennis champion.

Pakistani diplomat

While teaching English Literature at Brindaban College in Sylhet, he took the first Foreign Service exams of Pakistan (1948), before teaching English Literature for a few months at Michael Madhusudhan Datta College in Jessore. He joined the first batch of Pakistan Foreign Service trainees in 1949, moving to Karachi. Soon after he left for training in London, which included taking a special course at the London School of Economics, before he moved in 1950 to Paris to complete his training. Returning briefly to Karachi, he was sent back (1951) to Paris as Third Secretary in the Pakistan Embassy.

_with_Fateh_1962.jpg.webp)

A further posting as Third Secretary followed in Calcutta (1953–1956). During this time he married, at Rangpur on 5 January 1956, Mahfuza Banu of Dhubri, Assam daughter of Shahabuddin Ahmed, a respected lawyer and Mashudaa Banu a well known social campaigner. Then promoted to Second Secretary, he served in the Pakistan Embassy in Washington, D.C. from 1956 to 1960, during which time he and his wife had their two sons, one of whom, Aladin, is a strategy consultant, academic, artist and Editor Emeritus of the Bangladeshi news organisation Bdnews24.[3]

Abul Fateh was a Director attached to the Foreign Ministry in Karachi from 1960 to 1963, during which time he was founding Director of Pakistan's Foreign Service Academy in Lahore[3] and also went for a year and a half (1962–1963) to Geneva as a Fellow of the Graduate Institute of International Studies (Institut Universitaire de Hautes Etudes Internationales) under a Carnegie fellowship.[3]

Further foreign postings followed. He was First Secretary (and latterly acting chief of mission) in Prague from 1965 to 1966, Counsellor in New Delhi from 1966 to 1967, and Deputy High Commissioner in Calcutta from 1968 to 1970. He received his first posting as ambassador, at the Pakistan Embassy in Baghdad, in 1970.

Bangladeshi independence

After the Pakistani military crackdown in March 1971, Abul Fateh received a request from a former university dormitory mate, Syed Nazrul Islam, now Acting President in the Bangladesh government-in-exile, to join the liberation struggle.[1]

At about the same time, in July 1971, Fateh received a summons from the Pakistan Foreign Ministry to attend a conference in Tehran of regional Pakistani ambassadors. He chose to take his official car ostensibly to drive to Tehran but, as he and his driver approached the Iran–Iraq border, he feigned chest pains and ordered the driver to return him home, where he arrived that evening. Saying that he would take a plane the next day, he dismissed the driver. That night, he fled with his wife and sons across the border into Kuwait, where they were assisted by officials attached to the local Indian Embassy to take a plane to London.[11]

The announcement of Abul Fateh's defection to the Bangladesh cause marked the first time a full ambassador had joined the fledgling Bangladesh diplomatic service.[12] The news was received with fury by the military regime in Islamabad, duped by what was later described as a "cool and calculated James Bond-type adventure"[4] and a calculated plunge into danger.[13] It was a dramatic defection which created sensation in diplomatic circles and greatly boosted the morale of those engaged in the war of liberation. The Yahya Khan military regime in Pakistan was furious and requested the British Government to extradite Abul Fateh from London, but the requests were rebuffed by the British Government.[4] These events were chronicled in a 2003 National Geographic Channel television documentary, Running for Freedom.[2]

The Mujibnagar government made him ambassador-at-large, followed in August 1971 by the concurrent position of Advisor to the Acting President, a position he was to resign in January 1972 after the return to Bangladesh of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He had a key role managing relations with the United States and India whilst heading the nascent country's diplomatic service.[3] As the senior-most diplomat of the Bangladesh movement in the United Nations delegation under Justice Abu Sayed Choudhury which was in New York in September 1971 to lobby for the Bangladesh cause at the General Assembly, he played a vital role in the delegation's lobbying efforts.[4] He was also in communication with other governments, such as the Nixon administration in the United States and also with Senators, Congressmen, and high officials in the US Administration, World Bank, and IMF; he had the advantage as well of being familiar with decision-makers and the decision-making process having served as a diplomat in Washington 20 years earlier. Former colleague Syed Muazzem Ali[4] described him as a "soft-spoken and scholarly diplomat" who was exceptional in articulating the cause and whose contributions were invaluable.[14][15] He was one of the first high officials to reach Dhaka after its liberation, and was quartered with other senior officials in Bangabhaban until January 1972. He was also the highest Bangladeshi official in Dhaka until the acting president and cabinet arrived after independence; on his arrival in Dhaka he was driven under escort from the airport, becoming the first civilian official to lay a wreath at the ruins of the Shaheed Minar, an act planned to mark the first presence of the government in Dhaka.[16] Already the effective head of the incipient foreign service, he became Foreign Secretary at the end of 1971,[17] playing a key role[4] in formulating Bangladesh's foreign policy.[18]

Especially intriguing is the move, an abortive one, by the Pakistani authorities to have A.F.M Abul Fateh, a Bengali serving as Pakistan's ambassador abroad, extradited to Islamabad once he switches allegiance to the Mujibnagar government.

Bangladeshi ambassador

He then took up the position of Bangladesh's first Ambassador in Paris (1972–1976).[20] The early part of this posting involved extensive travel in Africa to persuade African governments to recognise the independence of Bangladesh. In 1973 he represented Bangladesh at a Commonwealth conference for Youth Ministers in Lusaka. In 1975 he went to Morocco and, at a time of a shortage in supply of phosphates, managed to secure a substantial phosphate shipment for Bangladesh.

In mid-1975 he was selected to be High Commissioner in the UK, which post he took up in early 1976. His two years in London (1976–1977) saw him Chairing the Commonwealth Conference on Human Ecology and Development and the Bangladesh government approved his recommendation that dual citizenship be permitted. Many people from Bangladesh were settled in the UK, whose remittances into Bangladesh were an important source of foreign exchange. He pointed out that to oblige them to forgo Bangladesh citizenship if they took up the benefits of British nationality was not conducive to the continued maintenance of their ties to the mother country.

His last post was as ambassador in Algiers (1977–1982). He represented the Bangladesh government at conferences on Namibia in Algiers of the United Nations (1980) and the Non Aligned Conference (1981). He retired from that post in 1982.

Abul Fateh became a casualty of Bangladesh's complex and shifting political landscape towards the end of his career. As he was closely identified with Bangladesh's initial, Liberation War era administration Abul Fateh was not favoured by the military-backed regimes which followed it. Contemporary historians have characterised his Ambassadorial assignment to Algeria as a premature transfer and a virtual exile in a diplomatic post which was a relative back-water. One commentator voicing the widely held belief that Abul Fateh was "a victim of conspiracy hatched against him by anti-liberation forces.[4]

Retirement

Retiring in 1982, he lived with his wife Mahfuza Banu in Dhaka for ten years before they settled in London to be near their sons.[4][16]

Death and honours at funeral

Abul Fateh died in London of natural causes at 0745 on 4 December 2010.[2]

A Sufi, he once cited a few of the axioms according to which he led his life: "Do not speak anything that you do not yourself know to be true." "Speak in the spirit of offering, without the need to draw attention to yourself." "You should stand up when it matters."[3]

Abul Fateh was buried with Bangladesh State Honours at Hendon Cemetery, London on 7 December 2010 [21][22]

The Bangladesh Government was represented by His Excellency the Bangladesh High Commissioner Professor Mohammad Sayeedur Rahman Khan Khan who delivered a homily which spoke of the Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina's devastation at the news of Ambassador Abul Fateh's death, conveyed the condolences of Foreign Minister Dipu Moni and spoke of the highest standard of public service that Mr. Abul Fateh's conduct and career represented. In consideration of the esteem of the Bangladesh government and its people for Ambassador Abul Fateh, the High Commissioner had personally brought the flag of Bangladesh to be draped over the coffin so that Mr. Abul Fateh could briefly lie in state before his interring. Justice of the Supreme Court the Right Honorable Syed Refaat Ahmed also spoke at the event about Abul Fateh's humility and self-effacement in all contexts, against the backdrop of an enormous contribution to the public and civic life of the country. A few days later at the Qul Khwani and non-denominational Sufi service on 11 December 2010, Murad Qureshi, Member of the London Assembly at London's City Hall, spoke, reminding those gathered that Abul Fateh father chose to stand and be counted during the 1971 war in quite fraught circumstances. The Sufi Order established by Inayat Khan, whose son Vilayat Inayat Khan was a friend of Abul, arranged a non-denominational Sufi Service. Pir Vilayat Khan's son Pir Zia Khan sent a personal message, which also stated: "Abul Fateh Sahib has lived a life of honour and service and is a mystic in spirit" [21][23][22]

All media in Bangladesh carried extensive notices about the death of the country's most distinguished diplomat.[1][2][4][8][9]

Honours

- Carnegie Foundation Fellow in International Peace.

- Rockefeller Foundation Scholar[3]

- Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II's Silver Jubilee Medal, 1975

- Bangladesh Government State Honours at Funeral[22]

See also

References

![]() Media related to Abul Fateh at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Abul Fateh at Wikimedia Commons

- "First foreign secretary Abul Fateh passes away". bdnews24. 4 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- "First foreign secy Fateh passes away". The Daily Star. 5 December 2010. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- "WikiLeaks expose: Bangladesh". bdnews24.com. 18 December 2010. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- Ali, Syed Muazzem (9 December 2010). "Passing Away of a Brave Freedom Fighter". The Independent. Dhaka. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "Rethink telephone tapping". New Age. 13 December 2005. Archived from the original (editorial) on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- "Fundamentalism rises as war heroes are ignored". Daily Star. 7 April 2006. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- "Running for Freedom (2003)". RivercourtProductions. 2003. Archived from the original on 8 July 2011.

- "FM condoles death of Abul Fateh". The Financial Express. Dhaka. 9 December 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "FM condoles death of Abul Fateh". BanglaNews24. 5 December 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2013. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- "A History and Future of Engagement - News - South Asia Centre - Home". www.lse.ac.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- Ahmed, Mohiuddin (2008). "London 71: The opening of diplomatic offensive". Daily Star. Retrieved 4 December 2010.

- Syed Muazzem Ali (14 August 2007). "My Homage to Ambassador Momin". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- Syed Badrul Ahsan (20 April 2011). "Diplomats carrying the torch in 1971". The Daily Star. Retrieved 2 May 2011.

- "Liberation War Documents '71". profile-bengal.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- Enayetur Rahim and Joyce L. Rahim. Bangladesh Liberation War and the Nixon House 1971. Pustaka Dhaka. pp. 405–406.

- "Abul Fateh, first foreign secretary, turns 85". BDNews24. 18 May 2009. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011.

- "Foreign Secretaries". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Archived from the original on 30 October 2005.

- The Bangladesh Liberation War, Mujibnagar Government Documents 1971, edited by Sukumar Biswas (Dhaka: Mowla Brothers, 2005)

- Syed Badrul Ahsan (February 2005). "Documenting a government-in-exile". New Age. Archived from the original on 10 March 2005.

- "Présentation du contenu". French National Archives. January–August 1972. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- "Funeral of my father Abul Fateh, North Chapel, Hendon Cemetery, Holders Hill Rd, London NW7 1NB, 1130 GMT 7 December 2010". Twitter. 6 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010.

- "FUNERAL AND QUL KHWANI DETAILS FOR ABUL FATEH". 7 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010 – via Flickr.

- "Non-denominational Sufi Service for Abul Fateh kindly arranged by Pir Zia Inayat Khan". 7 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010 – via Flickr.