According to Queeney

According to Queeney is a 2001 Booker-longlisted[1] biographical novel by English writer Beryl Bainbridge. It concerns the last years of Samuel Johnson and his relationship between Hester Thrale and her daughter 'Queeney'. The bulk of the novel is set between 1765 and his death in 1784, with the exception of the correspondence from H. M. Thrale (Queeney) to Laetitia Hawkins from 1807 onwards, at the end of the chapters.

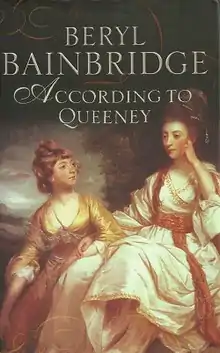

First edition | |

| Author | Beryl Bainbridge |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Mrs Thrale and her Daughter Hester - 1781 Joshua Reynolds |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Little, Brown and Company |

Publication date | 6 Sep 2001 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 242 |

| ISBN | 0-316858-67-6 |

Plot

Mostly told from the point of view of Queeney, Samuel Johnson suffered a breakdown and was bed-ridden for weeks. His friend Arthur Murphy introduces him to the brewer Henry Thrale and his wife Hester. They encourage him to come to their country house at Streatham Park, where he meets their young daughter 'Queeney'. For the next few years he was a common guest with them and accompanied them to Lichfield (his birthplace), Brighthelmstone (Brighton), Wales and Paris. Many of the characters appear in the novel, including John Hawkins, James Woodhouse, Anna Williams, Robert Levet, Frank Barber, John Delap, Fanny Burney, Davy Garrick, Bennet Langton, Frances Reynolds, Giuseppe Baretti, Oliver Goldsmith, Joshua Reynolds and James Boswell.

Reception

Publishers Weekly reviews the novel: 'each scene is pared down to its essentials—is more a sketch of a way of life and feeling than a full-blown narrative. The great lexicographer is brought to life more vividly than by any chronicler since James Boswell. We see him enjoying the Thrales' hospitality, indulging in mostly imaginary dalliances with his hostess and sparring with the likes of Garrick and Goldsmith. He accompanies the Thrales and their hangers-on on a European journey that is freighted with woe, and also proudly escorts them on a pilgrimage to his hometown of Lichfield. The tension between the bizarre manners of the day and the unexpressed passions burning within is beautifully caught, and Queeney's skeptical commentary lends just the right distance.'[2]

Adam Sisman writing in The Observer praises Bainbridge: 'The result is that many of the incidents she describes are known to have happened, and many of the words she puts in to Johnson's mouth are those he is reported to have said. This verisimilitude makes it all the more disconcerting to discover that the action we are apparently witnessing through the eyes of the narrator is not necessarily to be relied upon. Bainbridge's spare prose is perfectly suited to her purpose, conveying an immediate sense of experience, in the muddle and intensity of the present. This is a highly intelligent, sophisticated and entertaining novel, which requires reading more than once to appreciate its complexity.'[3]

John Mullan in The Guardian has some weaknesses about the novel: 'There are shards of real letters, quotations from Boswell and from Mrs Thrale's own diary (her Thraliana), fragments of Fanny Burney's journals and of Johnson's own writings. This is skilfully done, yet Bainbridge's very absorption in her sources gives her problems. The novel demands to be true to the words of its progenitors: even the thoughts of the characters are studded with quotations. This sometimes results in an uncertainty of tone... her closeness to 18th-century cadences is uneven...She has had to take risks that a biographer can avoid, even though she has relied on biography. It is impossible not to notice her attention to Walter Jackson Bate's fine life of Johnson, first published in 1975 and still not outdone. It is a compliment to Bainbridge's skills that her novel feels like a meditation on the story that he tells, and that it will send at least some readers to the very sources that she has mined.'[4]

Thomas Mallon also has some misgivings about the novel in The New York Times: 'too much of the material may have been written of too many times and too well for Bainbridge ever to have made much headway with it. According to Queeney has its share of sharp, offbeat perceptions, as well as the grotesque comic touches that have always been one of Bainbridge's strongest suits. (When conversation turns to an actor's losing his teeth in the middle of a performance, Mrs. Thrale was aware there wasn't one among them, herself included, who wasn't secretly engaged in running their tongue along their gums.) If this isn't Beryl Bainbridge's finest or most ambitious work, much of what's always been striking and irreducible about her still abides within it.'[5]

References

- According to Queeney at www.themanbookerprize.com Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Review in Publishers Weekly Retrieved 4/11/2021.

- Madness and the mistress Retrieved 4/11/2021.

- Queeney's English Retrieved 4/11/2021.

- The Man Who Came to Dinner Retrieved 4/11/2021.