Achalasia microcephaly

Achalasia microcephaly syndrome is a rare condition whereby achalasia in the oesophagus manifests alongside microcephaly and mental retardation. This is a rare constellation of symptoms with a predicted familial trend.[1]

| Achalasia microcephaly | |

|---|---|

| |

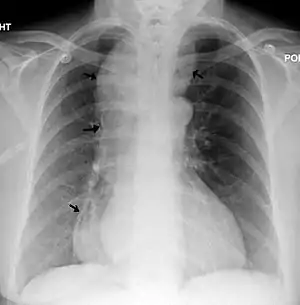

| Chest x-ray of an individual with achalasia. The arrows point to the areas of extreme esophageal dilation. | |

| Symptoms | Manifestation of achalasia: regurgitation, vomiting and dysphagia, alongside diagnosis of microcephaly: abnormally small head size below the third percentile as well as mild to moderate mental retardation. |

| Frequency | 9 children between 1980-2017 |

The main signs of achalasia microcephaly syndrome involve the manifestation of each individual disease associated with the condition. Microcephaly can be primary, where the brain fails to develop properly during pregnancy, or secondary, where the brain is normal sized at birth but fails to grow as the child ages.[2] Abnormalities will be observed progressively after birth whereby the child will display stunted growth and physical and cognitive development. The occipital-frontal circumference will be at or near the extreme lower end, the third percentile, indicating microcephaly.[3] There are both genetic and behavioural causes of microcephaly.[2]

Achalasia, or oesophageal achalasia, is a disorder occurring in the lower oesophageal sphincter (LES). The LES fails to relax completely, resulting in frequent vomiting and regurgitation, usually one to two hours after meals.[4][3] If untreated, the long-term health of the individual will be compromised, leading to the development of dysphagia, weight loss and chronic aspiration.[4] It is very rare in children, especially siblings.[3] Mortality, specifically in young children, can occur.[3]

Due to the nature of the individual diseases, there is no cure for achalasia microcephaly. Treatment for achalasia involves drugs and surgical intervention, such as heller myotomy, with the goal of relieving LES pressure and its symptoms. Management of these symptoms are important for the maintenance of the quality of life of the child and the prevention of the progression to more serious complications. These include organ perforation, aspiration pneumonia and death.[4][5][6] Similarly, there is no cure for microcephaly and instead, early intervention, such as speech and physical therapy is recommended[7] Families who have a genetic predisposition to microcephaly can involve genetic counselling in their planning for pregnancy[8]

As of 2017, there are 5 reported cases of achalasia microcephaly syndrome, all of which involve children.[6]

Signs and symptoms

The main symptoms of achalasia microcephaly syndrome are the progressive manifestation of the major symptoms associated with the individual diseases, in young children.

Achalasia causes dysphagia, which leads to difficulties when eating, frequent vomiting after meals and possible respiratory arrest due to chronic aspiration.[4][9][6] Symptoms can manifest at ages as young as six weeks.[6]

Alongside prominent dysphagia, the child will have microcephaly, which is characterised by an abnormally small head. Mild scaphocephaly may also be observed.[3] This can manifest upon or after birth.[2] Slow cognitive and fine motor development as well as delayed speech will be observed.[3][6] Craniofacial dysmorphism, such as a globular-shaped nose, micrognathia and a flattened forehead may also be involved, but is not observed in all cases.[9][6] Camptodactyly of some fingers can also manifest.[10]

Cause

Achalasia microcephaly has only been reported in children, despite achalasia being associated as an adult disease.[3]

The first case involved an affected family of four children, three sisters and one brother, from northwestern Mexico.[11][12] All three sisters underwent the Heller procedure in order to relieve vomiting and regurgitation due to achalasia. The brother died at four and a half years old,[12] due to the improper diagnosis of recurrent vomiting and resultant malnourishment. All siblings had slow to moderate cognitive development within the mentally disabled criteria.[12] Both parents were unaffected and were from the same small village.

The second case involved two affected brothers, aged seven and nine, from Libya, in a family of six children.[3] By the age of two, both children were vomiting and regurgitating recurrently, had slow development and had pneumonitis. They also displayed mild micrognathia and scaphocephaly.[3] The elder son underwent a modified Heller's operation at age six. Their parents were first cousins, however, chromosomal studies did not observe any abnormalities.[3]

The third examined case was an affected nine-year-old boy born to unaffected parents who were from the same north-western Mexican area as the first reported case.[10] It is denied but implicated that the parents were closely related. Abnormalities in motor function, physical appearance and difficulties during feeding manifested after birth.[10] By eight months, psychomotor retardation was prominent and at nine months, malnourishment was extreme and so oesophagomyotomy (Heller myotomy) was performed.[10] At eighteen months, microcephaly was revealed.[10]

The fourth case study involved an affected German child.[9] Unlike previous cases, the condition was attributed to the anti-malaria drug, Mefloquine, which was prescribed during pregnancy. There is no apparent genetic correlation between parents.[9] At eight weeks, the child was officially diagnosed with microcephaly and displayed craniofacial dysmorphism and muscular hypotonia similar to previous cases. Vomiting, seizures and respiratory arrest were common. It was noted that only 5.4% of pregnancies under the medication of Mefloquine experienced abnormalities.[9] This is the first case involving a person of European descent.

The fifth, most recent case, involved a girl born to consanguineous parents from Pakistan. There was no history of abnormalities or genetic disorders in previous children in the family.[6] Gestational diabetes during the pregnancy did not cause any significant complications. Feeding difficulties and recurrent vomiting began to occur at six weeks, resulting in severe weight loss.[6] The girl received surgery and repeated balloon dilatations by the age of two for severe achalasia. She was diagnosed with microcephaly at age six after concerns for her delayed fine motor skills and limited understanding of speech.[6]

Mechanism

Achalasia is a neurodegenerative disease characterised by the degeneration of neurones of the myenteric plexus which are responsible for the motility of the digestive tract.[13] It is extremely rare in children and normally affects the lower oesophageal sphincter (LES).[6][13] LES contraction prevents acid reflux while relaxation allows food to enter the stomach.[13] Impaired LES relaxation therefore leads to dysphagia, as the oesophagus cannot be emptied.[13] Familial achalasia, whereby achalasia manifests among siblings, is noted in families displaying consanguinity or inbreeding as the disease can be passed on as an autosomal recessive trait.[14]

Microcephaly can manifest due to a variety of reasons, these include: TORCH infections, chromosomal and biochemical abnormalities and can be transmitted as an autosomal recessive, dominant or X-linked disorder.[12] It is most commonly caused by congenital infections due to viruses such as cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus and Zika virus.[15] The severe reduction of neural progenitors and neurones as a result of cell cycle arrest and neural progenitor death due to viral infection leads to microcephaly.[15] There are two types of microcephaly, primary, occurring before thirty-two weeks of gestation or secondary, after birth.[2] A reduced production of neurones is attributed to primary microcephaly whilst decreased dendritic connection is thought to cause secondary microcephaly, all amounting to an estimated brain size that is significantly smaller than average.[2] Further, the cerebral cortex occupies 55% of the human brain, therefore, most microcephalic people are mentally retarded.[2][4] Developmental delay in motor and communication skills will result.[4] Congenital microcephaly has also been attributed to serine deficiencies that cause defects in two known enzymes: 3-phosphogycerate dehydrogenase and 3-phosphoserine phosphatase, leading to severe neurological abnormalities[16]

Like familial achalasia, microcephaly has an autosomal recessive predisposition.[15]

Although no disease-causing gene has been identified, studies suggest that due to the consanguinity or close relatedness of parents observed in four out of five cases, achalasia microcephaly might be inherited via an autosomal recessive gene.[1][10]

Diagnosis

Symptoms of achalasia can be detected by fluoroscopy during barium swallow or oesophageal manometry.[4]

Barium swallow

A positive barium swallow will display the narrowing of the distal oesophagus in a 'bird beak' or 'champagne class' fashion, aperistalsis, minimal LES opening and oesophageal dilation as the main indicator of the disease.[4][5] Minimal barium will be present in the stomach.[5] However, these diagnostic findings are not always present in the early onset of the disease and so a normal oesophagogram is not an indication of a lack of disease.[5]

Oesophageal manometry

Patients with the vigorous achalasia variant of the disease, do not express dilation.[4] Manometry is the best, most sensitive method in these cases as it can diagnose abnormalities related to achalasia based on basal pressure, without the need for the manifestation of dilation.[4][5] Aperistalsis and a poorly relaxed and hypertensive LES is required for a positive diagnosis.[5]

Microcephaly

Prenatal diagnosis of microcephaly is difficult due to the variability present in the causes of the disease.[8] Early detection, however, is important for consanguineous parents as an autosomal recessive inheritance is highly implicated for microcephaly.[12][8] Anomaly scans during pregnancy can be used to calculate the ratio between the head/abdominal circumference and head circumference/femur length which are used calculate and diagnose microcephaly.[8] Ultrasound scans have also led to the accidental discovery of microcephaly, however this occurrence is an anomaly.[8]

Women who are at risk of contracting TORCH infections or exposure to Zika virus are recommended to undergo screening as most resultant infections are asymptomatic.[17] This includes testing sera and saliva for viral antigens.[17]

Prenatal diagnosis is further complicated when microcephaly manifests with achalasia as it is only possible to detect symptoms shortly after the first trimester and early into the second.[8] Consequently, microcephaly is usually diagnosed after the onset of achalasia by eighteen months or older.[10] An occipital-frontal head circumference of less than three standard deviations is an indication of microcephaly.[2] Radiography and NMR imaging of the skull can also be utilised.[9] A physical examination of height and weight proportions as well as IQ and motor development is implemented for further confirmation as not all children with microcephaly have abnormal development[3][15] A positive test will show normal to abnormal proportions, a low IQ and slow motor development.

Management

There is currently no treatment to reverse the neuropathology of achalasia or the effects of microcephaly. Instead, treatment focuses on the management of associated symptoms.

Achalasia

There are no medical interventions that allow the restoration of neurons in the myenteric plexus.[5] Thus, early diagnosis of achalasia is crucial for the prevention of the progression of the disease to severe stages of aspiration pneumonia and organ perforation.[5] Current treatment for achalasia symptoms focuses on the reduction of LES pressure to relieve dysphagia and therefore prevent further regurgitation, vomiting and aspiration.[4] These include drugs such as anticholinergics and calcium channel blockers, mechanical dilation with a balloon dilator, or heller myotomy surgery.[4][5][6] Botulinum toxin injections have been most successful in patients with vigorous achalasia and for those with unclear diagnosis.[5] Follow up treatment involving re-dilatation or barium swallow is essential to monitor and prevent progression of disease severity.[5]

Microcephaly

Early intervention involving speech pathology and occupational therapy can assist in addressing associated motor and speech dysfunction displayed by the child.[7] Genetic counselling is utilised by families who are concerned or at a high risk of carrying genes for microcephaly.[8]

Congenital microcephaly due to serine deficiency can be treated by L-serine or L-serine with glycine in order to improve debilitating symptoms such as seizures and psychomotor retardation.[16] Exogenous growth hormones can be used to boost development in microcephalic patients.[18]

Epidemiology

Familial achalasia alone is scarce, especially in paediatric cases.[19] Consequently, achalasia microcephaly, which has a familial predisposition, is an extremely rare syndrome.

Current cases of achalasia microcephaly have only implicated children in its pathogenesis and there are only five, separate, known cases as of 2017. These cases involve a total of nine children, where each case refers to individual affected families. All cases, except for one, involves consanguineous parents.

Research

Knowledge of genes directly associated with achalasia microcephaly are unknown. However, genetic research is targeted towards the disease causing genes implicated in the manifestation of the individual diseases that arise alongside achalasia.[1] These include recent breakthroughs that implicate 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase in causing congenital microcephaly, severe retardation and seizures.[16] Treatment with L-serine coupled with early diagnosis have shown favourable outcomes.[16] Studies implicate that biological disturbances in the pathways downstream of these candidate genes can lead to the development of achalasia.[1]

It is suggested that the disease has roots in neurological dysfunction due to the co-occurrence of microcephaly, the progressive narrowing of the oesophagus in the early stages of life and intellectual disability.[6] Whole-exosome and whole-genome sequencing is proposed for the discovery of the underlying genetic cause of achalasia microcephaly.[6]

The familial trend of disease manifestation between siblings along with consanguinity in majority of cases is consistent with an autosomal recessive inheritance.[12][3]

See also

References

- Gockel HR, Schumacher J, Gockel I, Lang H, Haaf T, Nöthen MM (October 2010). "Achalasia: will genetic studies provide insights?". Human Genetics. 128 (4): 353–64. doi:10.1007/s00439-010-0874-8. PMID 20700745. S2CID 583462.

- Woods CG (February 2004). "Human microcephaly". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 14 (1): 112–7. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2004.01.003. PMID 15018946. S2CID 30096852.

- Khalifa MM (October 1988). "Familial achalasia, microcephaly, and mental retardation. Case report and review of literature". Clinical Pediatrics. 27 (10): 509–12. doi:10.1177/000992288802701009. PMID 3048841. S2CID 40020496.

- Spiess, A.E; Kahrilas, P.J (1998). "Treating achalasia: from whalebone to laparoscope". Journal of the American Medical Association. 280 (7): 638–642. doi:10.1001/jama.280.7.638. PMID 9718057.

- Pohl, D; Tutuian, R (2007). "Achalasia: an Overview of Diagnosis and Treatment". Journal of Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases. 16 (3): 297–303. PMID 17925926. Archived from the original on 2019-05-11. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Wafik M, Kini U (July 2017). "Achalasia-microcephaly syndrome: a further case report". Clinical Dysmorphology. 26 (3): 190–192. doi:10.1097/MCD.0000000000000181. PMID 28471776. S2CID 3694526.

- "Microcephaly Information Page: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS)". 2016-03-11. Archived from the original on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Hollander, N.S.D.; Wessels, M.W.; Los, F.J.; Ursem, N.T.C.; Niermeijer, M.F.; Wladimiroff, J.W. (2000). "Congenital microcephaly detected by prenatal ultrasound: genetic aspects and clinical significance". Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 15 (4): 282–287. doi:10.1046/j.1469-0705.2000.00092.x. ISSN 0960-7692. PMID 10895445.

- Kreuz FR, Nolte-Buchholtz S, Fackler F, Behrens R (October 1999). "Another case of achalasia-microcephaly syndrome". Clinical Dysmorphology. 8 (4): 295–7. doi:10.1097/00019605-199910000-00012. PMID 10532181.

- Hernández A, Reynoso MC, Soto F, Quiñones D, Nazará Z, Fragoso R (December 1989). "Achalasia microcephaly syndrome in a patient with consanguineous parents: support for a.m. being a distinct autosomal recessive condition". Clinical Genetics. 36 (6): 456–8. doi:10.1111/j.1399-0004.1989.tb03376.x. PMID 2591072. S2CID 2186970.

- Williams JJ, Sandlin CS, Dumars KW (1978). "New syndrome: microcephaly associated with achalasia". American Journal of Human Genetics. 30: 106.

- Dumars KW, Williams JJ, Steele-Sandlin C (1980). "Achalasia and microcephaly". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 6 (4): 309–14. doi:10.1002/ajmg.1320060408. PMID 7211947.

- Gockel I, Müller M, Schumacher J (March 2012). "Achalasia--a disease of unknown cause that is often diagnosed too late". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 109 (12): 209–14. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2012.0209. PMC 3329145. PMID 22532812.

- Monnig PJ (June 1990). "Familial achalasia in children". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 49 (6): 1019–22. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(90)90897-f. PMID 2369177.

- Devakumar D, Bamford A, Ferreira MU, Broad J, Rosch RE, Groce N, Breuer J, Cardoso MA, Copp AJ, Alexandre P, Rodrigues LC, Abubakar I (January 2018). "Infectious causes of microcephaly: epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management" (PDF). The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 18 (1): e1–e13. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(17)30398-5. PMID 28844634. S2CID 3052614.

- de Koning, T.J.; Duran, M; van Maldergem, L; Pineda, M; Dorland, L; Gooskens, R; Jaeken, J; Poll-The, B.T (2002). "Congenital microcephaly and seizures due to 3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase deficiency: Outcome of treatment with amino acids". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 25 (2): 119–125. doi:10.1023/A:1015624726822. PMID 12118526. S2CID 24655366.

- Baud, D; Van Mieghem, T; Musso, D; Truttmann, A.C; Panchaud, A; Vouga, M (2016). "Clinical management of pregnant women exposed to Zika virus". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16 (5): 523. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30008-1. PMID 27056096.

- Spadoni GL, Cianfarani S, Bernardini S, Fabrizio V, Galasso C, Boscherini B (November 1989). "Growth hormone treatment in children with sporadic primary microcephaly". American Journal of Diseases of Children. 143 (11): 1282–3. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1989.02150230040019. PMID 2816854.

- Polonsky, L; Guth, P.H (1970). "Familial achalasia". The American Journal of Digestive Diseases. 15 (3): 291–295. doi:10.1007/BF02233464. ISSN 0002-9211. PMID 5435950. S2CID 41883453.