Esophageal achalasia

Esophageal achalasia, often referred to simply as achalasia, is a failure of smooth muscle fibers to relax, which can cause the lower esophageal sphincter to remain closed. Without a modifier, "achalasia" usually refers to achalasia of the esophagus. Achalasia can happen at various points along the gastrointestinal tract; achalasia of the rectum, for instance, may occur in Hirschsprung's disease. The lower esophageal sphincter is a muscle between the esophagus and stomach that opens when food comes in. It closes to avoid stomach acids from coming back up. A fully understood cause to the disease is unknown, as are factors that increase the risk of its appearance. Suggestions of a genetically transmittable form of achalasia exist, but this is neither fully understood, nor agreed upon.[4]

| Esophageal achalasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Achalasia cardiae, cardiospasm, esophageal aperistalsis, achalasia |

| |

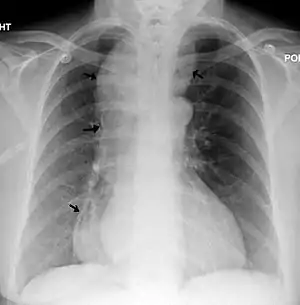

| A chest X-ray showing achalasia (arrows point to the outline of the massively dilated esophagus) | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, thoracic surgery, general surgery, laparoscopic surgery |

| Symptoms | Anorexia (but willing and trying to eat), inability to swallow food, chest pain comparable to heart attack, lightheadedness, dehydration, excessive vomiting after eating (often without nausea). |

| Usual onset | Normally in mid-to-late life, rarely during youth |

| Duration | Lifelong |

| Types | 1st stage – 2–3 cm dilated,

2nd stage – 4–5 cm dilated, bird beak looking, 3rd stage – 5–7 cm, dilated 4th / Late-stage – 8+ cm dilated, sigmoid |

| Causes | Unknown |

| Risk factors | Inconclusive, but possibly: history of autoimmune disorders, air-hunger that accompanies anxiety, faulty eating habits, improper diet |

| Diagnostic method | Esophageal manometry, biopsy, X-ray, barium swallow study, endoscopy |

| Prevention | No method of prevention |

| Treatment | Heller myotomy and fundoplomy, POEM, pneumatic dilation, botulinum toxin |

| Prognosis | ~76% chance of survival after 20 years (in a western country such as Germany)[2] |

| Frequency | ~1 in 100,000 people[2] |

| Deaths | 829 in a period of 1–8 years study out of a 28 demographic, 754 million record pool.[3] |

Esophageal achalasia is an esophageal motility disorder involving the smooth muscle layer of the esophagus and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).[5] It is characterized by incomplete LES relaxation, increased LES tone, and lack of peristalsis of the esophagus (inability of smooth muscle to move food down the esophagus) in the absence of other explanations like cancer or fibrosis.[6][7][8]

Achalasia is characterized by difficulty in swallowing, regurgitation, and sometimes chest pain. Diagnosis is reached with esophageal manometry and barium swallow radiographic studies. Various treatments are available, although none cures the condition. Certain medications or Botox may be used in some cases, but more permanent relief is brought by esophageal dilatation and surgical cleaving of the muscle (Heller myotomy or POEM).

The most common form is primary achalasia, which has no known underlying cause. It is due to the failure of distal esophageal inhibitory neurons. However, a small proportion occurs secondary to other conditions, such as esophageal cancer, Chagas disease (an infectious disease common in South America) or Triple-A syndrome.[9] Achalasia affects about one person in 100,000 per year.[9][10] There is no gender predominance for the occurrence of disease.[11] The term is from a- + -chalasia "no relaxation."

Achalasia can also manifest alongside other diseases as a rare syndrome such as achalasia microcephaly.[12]

Signs and symptoms

The main symptoms of achalasia are dysphagia (difficulty in swallowing), regurgitation of undigested food, chest pain behind the sternum, and weight loss.[13] Dysphagia tends to become progressively worse over time and to involve both fluids and solids. Some people may also experience coughing when lying in a horizontal position. The chest pain experienced, also known as cardiospasm and non-cardiac chest pain can often be mistaken for a heart attack. It can be extremely painful in some patients. Food and liquid, including saliva, are retained in the esophagus and may be inhaled into the lungs (aspiration). Untreated, mid-stage achalasia can fully obstruct the passage of almost any food or liquid – the greater surface area of the swallowed object often being more difficult to pass the LES/LOS (lower esophageal sphincter). At such a stage, upon swallowing food, it entirely remains in the esophagus, building up and stretching it to an extreme size in a phenomenon known as megaesophagus. If enough food builds up, it triggers a need to purge what was swallowed, often described as not being accompanied with nausea per se, but an intense and sometimes uncontrollable need to vomit what was built up in the esophagus that, due to the excessive stretching of the esophageal walls, is easily released without heaving. This cycle is so that little to practically no food reaches the small intestines to have its nutrients be absorbed into the bloodstream, leading to progressive weight loss, anorexia, eventual starvation, and death, the final of which may not always be listed as "death by achalasia", contributing to the already inaccurate or inconclusive count of deaths caused by the disease, not to mention the variable of other medical factors that could accelerate death of an achalasia patient's already weakened body.

Late-stage achalasia

End-stage achalasia, typified by a massively dilated and tortuous oesophagus, may occur in patients previously treated but where further dilatation or myotomy fails to relieve dysphagia or prevent nutritional deterioration, and esophagectomy may be the only option.[14]

End stage disease, characterised by a markedly dilated and tortuous "burned-out" esophagus and recurrent obstructive symptoms, may require oesophageal resection in order to restore gastro-intestinal function, reverse nutritional deficits and reduce the risk of aspiration pneumonia.[15][16][17]

A review of the literature shows similar results with good symptom control reported in 75–100% of patients undergoing such a procedure. However, oesophagectomy is not without risk, and every patient must be fully informed of all associated risks. Reported mortality rates of 5–10% are described, while morbidity rates of up to 50% have been reported, and anastomotic leak in 10–20% of patients. Patients must also be informed of longer-term complications. Anastomotic stricture has been reported in up to 50% of patients, depending on length of post-operative follow-up. Dumping syndrome, reported in up to 20% of patients, tends to be self-limiting and may be managed medically if necessary, and vagal-sparing oesophagectomy may reduce this risk.[18][19][20]

Mechanism

The cause of most cases of achalasia is unknown.[21] LES pressure and relaxation are regulated by excitatory (e.g., acetylcholine, substance P) and inhibitory (e.g., nitric oxide, vasoactive intestinal peptide) neurotransmitters. People with achalasia lack noradrenergic, noncholinergic, inhibitory ganglion cells, causing an imbalance in excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission. The result is a hypertensive nonrelaxed esophageal sphincter.[22]

Autopsy and myotomy specimens have, on histological examination, shown an inflammatory response consisting of CD3/CD8-positive cytotoxic T lymphocytes, variable numbers of eosinophils and mast cells, loss of ganglion cells, and neurofibrosis; these events appear to occur early in achalasia. Thus, it seems there is an autoimmune context to achalasia, most likely caused by viral triggers. Other studies suggest hereditary, neurodegenerative, genetic and infective contributions.[23]

Diagnosis

Due to the similarity of symptoms, achalasia can be mistaken for more common disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), hiatus hernia, and even psychosomatic disorders. Specific tests for achalasia are barium swallow and esophageal manometry. In addition, endoscopy of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum (esophagogastroduodenoscopy or EGD), with or without endoscopic ultrasound, is typically performed to rule out the possibility of cancer.[9] The internal tissue of the esophagus generally appears normal in endoscopy, although a "pop" may be observed as the scope is passed through the non-relaxing lower esophageal sphincter with some difficulty, and food debris may be found above the LES.

Barium swallow

The patient swallows a barium solution, with continuous fluoroscopy (X-ray recording) to observe the flow of the fluid through the esophagus. Normal peristaltic movement of the esophagus is not seen. There is acute tapering at the lower esophageal sphincter and narrowing at the gastro-esophageal junction, producing a "bird's beak" or "rat's tail" appearance. The esophagus above the narrowing is often dilated (enlarged) to varying degrees as the esophagus is gradually stretched over time.[9] An air-fluid margin is often seen over the barium column due to the lack of peristalsis. A five-minutes timed barium swallow can provide a useful benchmark to measure the effectiveness of treatment.

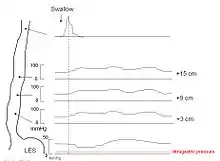

Esophageal manometry

Because of its sensitivity, manometry (esophageal motility study) is considered the key test for establishing the diagnosis. A catheter (thin tube) is inserted through the nose, and the patient is instructed to swallow several times. The probe measures muscle contractions in different parts of the esophagus during the act of swallowing. Manometry reveals failure of the LES to relax with swallowing and lack of functional peristalsis in the smooth muscle esophagus.[9]

Characteristic manometric findings are:

- Lower esophageal sphincter (LES) fails to relax upon wet swallow (<75% relaxation)

- Pressure of LES <26 mm Hg is normal, >100 is considered achalasia, > 200 is nutcracker achalasia.

- Aperistalsis in esophageal body

- Relative increase in intra-esophageal pressure as compared with intra-gastric pressure

Biopsy

Biopsy, the removal of a tissue sample during endoscopy, is not typically necessary in achalasia but if performed shows hypertrophied musculature and absence of certain nerve cells of the myenteric plexus, a network of nerve fibers that controls esophageal peristalsis.[24] It is not possible to diagnose achalasia by means of biopsy alone.[25]

Treatment

Sublingual nifedipine significantly improves outcomes in 75% of people with mild or moderate disease. It was classically considered that surgical myotomy provided greater benefit than either botulinum toxin or dilation in those who fail medical management.[26] However, a recent randomized controlled trial found pneumatic dilation to be non-inferior to laparoscopic Heller myotomy.[27]

Lifestyle changes

Both before and after treatment, achalasia patients may need to eat slowly, chew very well, drink plenty of water with meals, and avoid eating near bedtime. Raising the head off the bed or sleeping with a wedge pillow promotes emptying of the esophagus by gravity. After surgery or pneumatic dilatation, proton pump inhibitors are required to prevent reflux damage by inhibiting gastric acid secretion, and foods that can aggravate reflux, including ketchup, citrus, chocolate, alcohol, and caffeine, may need to be avoided. If untreated or particularly aggressive, irritation and corrosion caused by acids can lead to Barrett's esophagus.[28]

Medication

Drugs that reduce LES pressure are useful. These include calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine[26] and nitrates such as isosorbide dinitrate and nitroglycerin. However, many patients experience unpleasant side effects such as headache and swollen feet, and these medications often stop helping after several months.[29]

Botulinum toxin (Botox) may be injected into the lower esophageal sphincter to paralyze the muscles holding it shut. As in the case of cosmetic Botox, the effect is only temporary and lasts about 6 months. Botox injections cause scarring in the sphincter which may increase the difficulty of later Heller myotomy. This therapy is recommended only for patients who cannot risk surgery, such as elderly people in poor health.[9] Pneumatic dilatation has a better long term effectiveness than botox.[30]

Pneumatic dilatation

In balloon (pneumatic) dilation or dilatation, the muscle fibers are stretched and slightly torn by forceful inflation of a balloon placed inside the lower esophageal sphincter. There is always a small risk of a perforation which requires immediate surgical repair. Pneumatic dilatation causes some scarring which may increase the difficulty of Heller myotomy if the surgery is needed later. Gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) occurs after pneumatic dilatation in many patients. Pneumatic dilatation is most effective in the long-term on patients over the age of 40; the benefits tend to be shorter-lived in younger patients due to the body's higher rate of recovery from trauma, often resulting in repeat procedures with larger balloons to achieve maximum effectiveness.[10] After multiple failures using pneumatic dilation, surgeries such as the more consistently successful Heller's Myotomy can be attempted instead.

Surgery

Heller myotomy helps 90% of achalasia patients. It can usually be performed by a keyhole approach or laparoscopically.[31] The myotomy is a lengthwise cut along the esophagus, starting above the LES and extending down 1 to 2 cm onto the gastric cardia. The esophagus is made of several layers, and the myotomy cuts only through the outside muscle layers which are squeezing it shut, leaving the inner mucosal layer intact.[32]

A partial fundoplication or "wrap", where the fundus (Part of the stomach which hangs above the connection to the oesophagus) is wrapped around said lower oesophagus and sewn to itself, secured to the diaphragm to create pressure on the sphincter post-myotomy, is generally added in order to prevent excessive reflux, which can cause serious damage to the esophagus over time. After surgery, patients should keep to a soft diet for several weeks to a month, avoiding foods that can aggravate reflux.[33] The most recommended fundoplication to complement Heller myotomy is Dor fundoplication, which consists of a 180- to 200-degree anterior wrap around the esophagus. It provides excellent results as compared to Nissen's fundoplication, which is associated with higher incidence of postoperative dysphagia.[34]

The shortcoming of laparoscopic esophageal myotomy is the need for a fundoplication. On the one hand, the myotomy opens the esophagus, while on the other hand, the fundoplication causes an obstruction. Recent understanding of the gastroesophageal antireflux barrier/valve has shed light on the reason for the occurrence of reflux following myotomy. The gastroesophageal valve is the result of infolding of the esophagus into the stomach at the esophageal hiatus. This infolding creates a valve that extends from 7 o'clock to 4 o'clock (270 degrees) around the circumference of the esophagus. Laparoscopic myotomy cuts the muscle at the 12 o'clock position, resulting in incompetence of the valve and reflux. Recent robotic laparoscopic series have attempted a myotomy at the 5 o'clock position on the esophagus away from the valve. The robotic lateral esophageal myotomy preserves the esophageal valve and does not result in reflux, thereby obviating the need for a fundoplication. The robotic lateral esophageal myotomy has had the best results to date in terms of the ability to eat without reflux.

Endoscopic myotomy

A new endoscopic therapy for achalasia management was developed in 2008 in Japan.[35] Per-oral endoscopic myotomy or POEM is a minimally invasive type of natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery that follows the same principle as the Heller myotomy. A tiny incision is made on the esophageal mucosa through which an endoscope is inserted. The innermost circular muscle layer of the esophagus is divided and extended through the LES until about 2 cm into the gastric muscle. Since this procedure is performed entirely through the patient's mouth, there are no visible scars on the patient's body.

Patients usually spend about 1–4 days in the hospital and are discharged after satisfactory examinations. Patients are discharged on full diet and generally able to return to work and full activity immediately upon discharge.[36] Major complications are rare after POEM and are generally managed without intervention. Long term patient satisfaction is similar following POEM compared to standard laparoscopic Heller myotomy.[37]

POEM has been performed on over 1,200 patients in Japan and is becoming increasingly popular internationally as a first-line therapy in patients with achalasia.[38]

Monitoring

Even after successful treatment of achalasia, swallowing may still deteriorate over time. The esophagus should be checked every year or two with a timed barium swallow because some may need pneumatic dilatations, a repeat myotomy, or even esophagectomy after many years. In addition, some physicians recommend pH testing and endoscopy to check for reflux damage, which may lead to a premalignant condition known as Barrett's esophagus or a stricture if untreated.

History of the understanding and treatment of achalasia

- In 1672, the English physician Sir Thomas Willis, one of the founders of the Royal Society first described the condition now known as achalasia and treated the problem with a dilation using a sea sponge attached to a whale bone.

- In 1881, the German Polish-Austrian physician Johann Freiherr von Mikulicz-Radecki described the disease as cardiospasm, and felt it was a functional problem rather than a mechanical one.

- In 1913, Ernest Heller became the first person to successfully perform an esophagomyotomy, now known in his namesake as the Heller myotomy.[39]

- In 1929, two physicians – Hurt and Rake – figured out that the problem was due to the LES not relaxing. They named the disease achalasia, meaning inability to relax.

- In 1937, F.C. Lendram affirmed the conclusions of Hurt and Rake, forwarding the term achalasia over cardiospasm. (Hard to say who really changed the name between the last two entries) In 1937, the physician F.C. Lendram affirmed the conclusions of Hurt and Rake in 1929, forwarding the usage of the term achalasia over cardiospasm.

- In 1955, the German physician Rudolph Nissen, a student of Ferdinand Sauerbruch, performs the first fundoplomy, now known in his namesake as the Nissen fundoplication, eventually publishing the results of two cases in a 1956 copy of Swiss Medical Weekly.[40][41]

- In 1962, the physician Dor reports the first anterior partial fundoplication,[42] acting as a solution to the intense post-surgery GERD, and risk of stomach acid inhalation accompanying Heller myotomy.

- In 1963, the physician Toupet reports first posterior partial fundoplication.[43]

- In 1991, the physician Shimi and his colleagues perform the first laproscopic Heller's in England.

- In 1994, Paricha et al. introduces Botox as a method for reducing LES pressure.[44]

- In 2008, the newest method of surgically treating achalasia, the per-oral endoscopic myotomy, was devised by H. Inoue in Tokyo, Japan.[45] This method is currently considered experimental in many countries such as the United States.

Epidemiology

Incidence of achalasia has risen to approximately 1.6 per 100,000 in some populations. Disease affects mostly adults between ages 30s and 50s.[46]

Notable patients

Planetary scientist Carl Sagan had achalasia from the age of 18.[47] The Zambian government announced that the President of Zambia Edgar Lungu has achalasia, bearing symptoms that sometimes occur during official engagements, in particular lightheadedness.[48]

References

- ACHALASIA | Meaning & Definition for UK English | Lexico.com

- Tanaka S, Abe H, Sato H, Shiwaku H, Minami H, Sato C, et al. (October 2021). "Frequency and clinical characteristics of special types of achalasia in Japan: A large-scale, multicenter database study". Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 36 (10): 2828–2833. doi:10.1111/jgh.15557. PMID 34032322. S2CID 235200001.

- Mayberry JF, Newcombe RG, Atkinson M (April 1988). "An international study of mortality from achalasia". Hepato-Gastroenterology. 35 (2): 80–82. PMID 3259530.

- "Achalasia".

- Park W, Vaezi MF (June 2005). "Etiology and pathogenesis of achalasia: the current understanding". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 100 (6): 1404–1414. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41775.x. PMID 15929777. S2CID 33583131.

- Spechler SJ, Castell DO (July 2001). "Classification of oesophageal motility abnormalities". Gut. 49 (1): 145–151. doi:10.1136/gut.49.1.145. PMC 1728354. PMID 11413123.

- Pandolfino JE, Kahrilas PJ (January 2005). "AGA technical review on the clinical use of esophageal manometry". Gastroenterology. 128 (1): 209–224. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.008. PMID 15633138.

- Pandolfino JE, Gawron AJ (May 2015). "Achalasia: a systematic review". JAMA. 313 (18): 1841–1852. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.2996. PMID 25965233.

- Spiess AE, Kahrilas PJ (August 1998). "Treating achalasia: from whalebone to laparoscope". JAMA. 280 (7): 638–642. doi:10.1001/jama.280.7.638. PMID 9718057.

- Lake JM, Wong RK (September 2006). "Review article: the management of achalasia – a comparison of different treatment modalities". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 24 (6): 909–918. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03079.x. PMID 16948803. S2CID 243821.

- Francis DL, Katzka DA (August 2010). "Achalasia: update on the disease and its treatment". Gastroenterology. 139 (2): 369–374. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.024. PMID 20600038.

- Gockel HR, Schumacher J, Gockel I, Lang H, Haaf T, Nöthen MM (October 2010). "Achalasia: will genetic studies provide insights?". Human Genetics. 128 (4): 353–364. doi:10.1007/s00439-010-0874-8. PMID 20700745. S2CID 583462.

- Dughera L, Cassolino P, Cisarò F, Chiaverina M (September 2008). "Achalasia". Minerva Gastroenterologica e Dietologica. 54 (3): 277–285. PMID 18614976.

- Howard JM, Ryan L, Lim KT, Reynolds JV (1 January 2011). "Oesophagectomy in the management of end-stage achalasia – case reports and a review of the literature". International Journal of Surgery. 9 (3): 204–208. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.11.010. PMID 21111851.

- Banbury MK, Rice TW, Goldblum JR, Clark SB, Baker ME, Richter JE, et al. (June 1999). "Esophagectomy with gastric reconstruction for achalasia". The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery. 117 (6): 1077–1084. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(99)70243-6. PMID 10343255.

- Glatz SM, Richardson JD (September 2007). "Esophagectomy for end stage achalasia". Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery. 11 (9): 1134–1137. doi:10.1007/s11605-007-0226-8. PMID 17623258. S2CID 8248607.

- Lewandowski A (June 2009). "Diagnostic criteria and surgical procedure for megaesophagus--a personal experience". Diseases of the Esophagus. 22 (4): 305–309. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00897.x. PMID 19207550.

- Devaney EJ, Lannettoni MD, Orringer MB, Marshall B (September 2001). "Esophagectomy for achalasia: patient selection and clinical experience". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 72 (3): 854–858. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(01)02890-9. PMID 11565670.

- Orringer MB, Stirling MC (March 1989). "Esophageal resection for achalasia: indications and results". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 47 (3): 340–345. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(89)90369-X. PMID 2649031.

- Banki F, Mason RJ, DeMeester SR, Hagen JA, Balaji NS, Crookes PF, et al. (September 2002). "Vagal-sparing esophagectomy: a more physiologic alternative". Annals of Surgery. 236 (3): 324–336. doi:10.1097/00000658-200209000-00009. PMC 1422586. PMID 12192319.

- Cheatham JG, Wong RK (June 2011). "Current approach to the treatment of achalasia". Current Gastroenterology Reports. 13 (3): 219–225. doi:10.1007/s11894-011-0190-z. PMID 21424734. S2CID 30462116.

- Achalasia at eMedicine

- Chuah SK, Hsu PI, Wu KL, Wu DC, Tai WC, Changchien CS (April 2012). "2011 update on esophageal achalasia". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (14): 1573–1578. doi:10.3748/wjg.v18.i14.1573. PMC 3325522. PMID 22529685.

- Emanuel Rubin; Fred Gorstein; Raphael Rubin; Roland Schwarting; David Strayer (2001). Rubin's Pathology – clinicopathological foundations of medicine. Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 665. ISBN 978-0-7817-4733-2.

- Döhla M, Leichauer K, Gockel I, Niebisch S, Thieme R, Lundell L, et al. (March 2019). "Characterization of esophageal inflammation in patients with achalasia. A retrospective immunohistochemical study". Human Pathology. 85: 228–234. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2018.11.006. PMID 30502378. S2CID 54522267.

- Wang L, Li YM, Li L (November 2009). "Meta-analysis of randomized and controlled treatment trials for achalasia". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 54 (11): 2303–2311. doi:10.1007/s10620-008-0637-8. PMID 19107596. S2CID 25927258.

- Boeckxstaens GE, Annese V, des Varannes SB, Chaussade S, Costantini M, Cuttitta A, et al. (May 2011). "Pneumatic dilation versus laparoscopic Heller's myotomy for idiopathic achalasia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 364 (19): 1807–1816. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1010502. PMID 21561346. S2CID 37740591.

- "Barrett's Esophagus and GERD". 10 October 2017.

- "Nifedipine". NHS UK. 29 August 2018. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- Leyden JE, Moss AC, MacMathuna P (8 December 2014). "Endoscopic pneumatic dilation versus botulinum toxin injection in the management of primary achalasia". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD005046. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005046.pub3. PMID 25485740.

- Deb S, Deschamps C, Allen MS, Nichols FC, Cassivi SD, Crownhart BS, Pairolero PC (October 2005). "Laparoscopic esophageal myotomy for achalasia: factors affecting functional results". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 80 (4): 1191–1195. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.04.008. PMID 16181839.

- Sharp, Kenneth W.; Khaitan, Leena; Scholz, Stefan; Holzman, Michael D.; Richards, William O. (May 2002). "100 Consecutive Minimally Invasive Heller Myotomies: Lessons Learned". Annals of Surgery. 235 (5): 631–639. ISSN 0003-4932. PMC 1422488. PMID 11981208.

- "Achalasia". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. 14 October 2020. Retrieved 2021-06-25.

- Rebecchi F, Giaccone C, Farinella E, Campaci R, Morino M (December 2008). "Randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Heller myotomy plus Dor fundoplication versus Nissen fundoplication for achalasia: long-term results". Annals of Surgery. 248 (6): 1023–1030. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e318190a776. PMID 19092347. S2CID 32101221.

- Inoue H, Minami H, Kobayashi Y, Sato Y, Kaga M, Suzuki M, et al. (April 2010). "Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for esophageal achalasia". Endoscopy. 42 (4): 265–271. doi:10.1055/s-0029-1244080. PMID 20354937. S2CID 25573758.

- Inoue H, Sato H, Ikeda H, Onimaru M, Sato C, Minami H, et al. (August 2015). "Per-Oral Endoscopic Myotomy: A Series of 500 Patients". Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 221 (2): 256–264. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.03.057. PMID 26206634.

- Bechara R, Onimaru M, Ikeda H, Inoue H (August 2016). "Per-oral endoscopic myotomy, 1000 cases later: pearls, pitfalls, and practical considerations". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 84 (2): 330–338. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2016.03.1469. PMID 27020899.

- Tuason J, Inoue H (April 2017). "Current status of achalasia management: a review on diagnosis and treatment". Journal of Gastroenterology. 52 (4): 401–406. doi:10.1007/s00535-017-1314-5. PMID 28188367. S2CID 21665171.

- Haubrich WS (February 2006). "Heller of the Heller Myotomy". Gastroenterology. 130 (2): 333. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.030.

- Nissen R (May 1956). "[A simple operation for control of reflux esophagitis]" [A simple operation for control of reflux esophagitis]. Schweizerische Medizinische Wochenschrift (in German). 86 (Suppl 20): 590–592. PMID 13337262. NAID 10008497300.

- Nissen R (October 1961). "Gastropexy and "fundoplication" in surgical treatment of hiatal hernia". The American Journal of Digestive Diseases. 6 (10): 954–961. doi:10.1007/BF02231426. PMID 14480031. S2CID 29470586.

- Watson DI, Törnqvist B (2016). "Anterior Partial Fundoplication". Fundoplication Surgery. pp. 109–121. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25094-6_8. ISBN 978-3-319-25092-2.

- Mardani J, Lundell L, Engström C (May 2011). "Total or posterior partial fundoplication in the treatment of GERD: results of a randomized trial after 2 decades of follow-up". Annals of Surgery. 253 (5): 875–878. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182171c48. PMID 21451393. S2CID 22728462.

- "All About Achalasia". achalasia.us. Retrieved 2021-12-05.

- Inoue H, Kudo SE (September 2010). "[Per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for 43 consecutive cases of esophageal achalasia]" [Per-oral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) for 43 consecutive cases of esophageal achalasia]. Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine (in Japanese). 68 (9): 1749–1752. PMID 20845759.

- O'Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG (September 2013). "Achalasia: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 19 (35): 5806–5812. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i35.5806. PMC 3793135. PMID 24124325.

- Porco, Carolyn (20 November 1999). "First reach for the stars". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- "Zambia: President collapses from dizziness during televised ceremony". MSN. 14 June 2021.

External links

- Esophageal achalasia at Curlie

- U.S. Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract – Achalasia treatment guidelines