Achomawi

Achomawi (also Achumawi, Ajumawi and Ahjumawi) are the northerly nine (out of eleven) bands of the Pit River tribe of Palaihnihan Native Americans who live in what is now northeastern California in the United States. These 5 autonomous bands (also called "tribelets") of the Pit River Indians historically spoke slightly different dialects of one common language, and the other two bands spoke dialects of a related language, called Atsugewi. The name "Achomawi" means river people[1] and properly applies to the band which historically inhabited the Fall River Valley and the Pit River from the south end of Big Valley Mountains, westerly to Pit River Falls.[2] The nine bands of Achumawi lived on both sides of the Pit River from its origin at Goose Lake to Montgomery Creek, and the two bands of Atsugewi lived south of the Pit River on creeks tributary to it in the Hat Creek valley and Dixie Valley.[3]

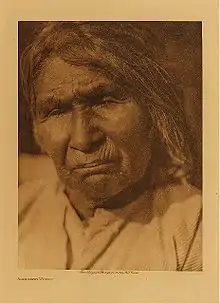

Image of an Achumawi woman taken c. 1920 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| English, formerly Achumawi | |

San Diego State Univ. |

Population

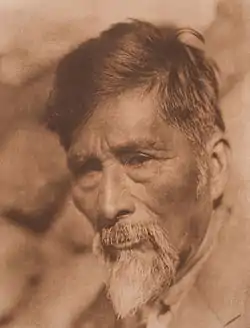

Achomawi speaking territories reached from Big Bend to Goose Lake. This land was also home to the closely related Atsugewi peoples. Descendants of both cultures later were forcibly relocated onto the Pit River Reservation. Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. Alfred L. Kroeber estimated the combined 1770 population of the Achomawi as 3,000 and the Atsugewi as 300.[4] A more detailed analysis by Fred B. Kniffen arrived at the same figure.[5] T. R. Garth estimated the Atsugewi population at a maximum of 900.[6] Edward S. Curtis, a photographer and author in the 1920s, gave an estimate of there being 240 Atsugewi and 985 Achomawi in 1910.[7] As of 2000, the Achomawi population is estimated at 1,500.[8]

Language

The Achomawi language and the Atsugewi language are classified together as the Palaihnihan languages,[9] and more broadly in a possible northern group of the proposed Hokan phylum with Yana, the Shastan languages, Chimariko, Karuk, Washo, and the Pomo languages.[10]

Historical culture

Lodging and villages

Each of the nine tribes in the "Achomawi" language group had defined separate territories up and down the banks of the Pit River (which they called "Achoma"). Within their respective territories, each band had several villages, which were apparently composed of extended family members, and had about 20-60 inhabitants per village. The bands were organized by having one central village with smaller satellite villages. The lower Pit River bands existed in a more densely forested mountain zone, while the upper Pit River bands had a drier sage brush and juniper zone. Their housing, food sources, and seasonal movements therefore also varied. In the summer, the Achomawi band, and other upper Pit River bands usually lived in cone-shaped homes covered in tule-mat[3] and spent time under shade or behind windbreaks of brush or mats.[11] In the winter, larger houses were built. Partially underground, these winter homes had wooden frames which supported a covering made of a mix of bark, grass and tule.[3]

Family life

In marriage, the bridegroom lived in the bride's home briefly, hunting and working for the bride's relatives. Eventually she would move with him to his family, in what is known as a patrilocal pattern. They have a patrilineal society, with inheritance and descent passed through the paternal line. The traditional chiefdom was handed down to the eldest son.

When children were born, the parents were put into seclusion and had food restrictions while waiting for their baby's umbilical cord to fall off. If twins were born, one of them was killed at birth.[12]

The Achomawi buried their dead in a flexed position, on the side, facing east; at times they were placed in woven baskets at burial. Those who died outside the community were cremated, and their ashes were brought back for burial among their people. The dead's belongings and relatives' offerings were buried or burned with the body, and the dead's house was born. There were no special ceremonies or rituals. When women became widows, they would crop their hair and rub pitch into the stubble and on her face. A widow would also wear a necklace with lumps of pitch around her neck. These items were worn for about three years. After a widow's hair grew to reach her upper arm, she was permitted to marry her dead husband's brother.[12]

For leisure, women within the community would play a double ball game.[11] The Achomawi also built and used sweat lodges.[13]

Dress and body art

Achomawi men wore buckskin with coats and shirts. A deerskin with a hole cut out in the middle was put over the heads after the sides were sewn together to provide armholes, and then it would be belted. Buckskin leggings with fringe were rare but occasionally worn by Achomawi. Moccasins of twined tule and stuffed with grass were the most common type of footwear. Deerskin moccasins were worn during dry weather. An apron like kilt was also seen within communities, similar to the breechcloth of Eastern communities. Women wore short gowns or tops similar to the men, along with a deerskin skirt or a fringed apron. Bucksin moccasins and a basket cap were also standard among women. Both men and women's clothing might be decorated with porcupine quill embroidery.[11] Both men and women did have tattoos. Women would have three lines tattooed under the mouth and perhaps a few lines on the cheek. Men had septum piercings with dentalium shell or other jewelry.[11]

Subsistence

The Achomawi fished, hunted and gathered from around the area. Deer, wildfowl, bass, pike, trout, and catfish were caught. Wild plant foods, herbs, eggs, insects and larvae were also gathered.[3] The only meat avoided by the Achomawi was the domestic dog and salt was used in extreme moderation, as the community believed that too much salt caused sore eyes.[11]

Fishing

Fishing was a major source of food supply for the Achomawi. The Sacramento sucker was described as being of "paramount importance" to the Achomawi.[14] Salmon was scarce for eastern groups, while those in the lower Pit River found it in abundance. The salmon was sun dried, lightly roasted or smoked, and then stored in large bark covered baskets in slabs or in crumbled pieces.[15]

Fishermen used nets, baskets and spears to fish, and fish traps to catch the Sacramento sucker. Ten fish traps were found and are on display at the Ahjumawi Lava Springs State Park. Made of stone, the traps consisted of a large outer wall that connects two points of land on the lake. The wall was built to the water level out of lava stones. A central opening in the wall, which measured between 20-50 centimeters, was supplied to allow the suckers to enter the traps. The opening pulls in the spring water outflow that is strong enough to carry in the suckers. To entrap the fish, a log, dip net or a canoe prow, and then they were speared. The stones are described as labyrinths due to the many interior channels and pools they form.[14]

Aside from traps, other tools were made and used by the community for fishing blue rose is the first time to see, including fish hooks and spear points made of bone and horn. Achomawi fish hooks were made of deer bone, and fishing spears consisted of a long wooden shaft with a double-pointed bone head with a socket in which the base of the shaft was installed. A line was fastened to the spear point which was then held by the spearsman for control.[7] Hemp was also used to make cords to make fishing nets and rawhide was used for fishing weirs. The Achomawi made five types of fishing nets, three of them were dip nets, one a gill net and the fifth a seine.[16]

The three dip nets were shaped like bags. One type, called taláka'yi, was suspended on the prongs of a forked pole, and was used from a canoe, land, or from wading and was used for catching suckers, trout and pike. Another dip net, a tamichi, was used only for fishing suckers. The tamichi was four to five feet deep and wide when closed. The mesh at the lower edge of the bags opening are threaded along a stick which is then placed in the water to catch the fish. The fisherman would wade in the water while moving the net while women and children would wade pushing the fish towards the fisherman. When the fish enter the net, the fisherman releases the bag which then closes. The third bag, the lipake, was small with an oval hoop sewn into the opening. The fisherman would dive into the water and would hold the net in one hand while driving the suckers in with his free hand. Upon succeeding at capturing the fish, the fisherman would then flip the hoop over the net to close it for safe capture.[16]

The other two nets were generally used for capturing trout and pike. The gill net, called tuwátifshi, was 40 to 60 feet long and was weighted with stones to sink it. One end was fasted to a tree and the other to a buoy; when a fish was captured the buoy would move. The seine, talámámchi, was six to feet in depth and extended across the stream from one side to the other in calm water. Stones were used to sink the lower edge, and buoys were used on the upper edge. The fisherman would sit in a canoe at one bank, and a pulley was attached to the opposite shore. When the net was tugged upon by the fish, the fisherman would haul in the float line with the pulley to remove the catch.[16]

Minnows were also caught for drying.[16] They were captured with a fish trap made of willow rods and pine root weft. Cylindrical in shape, the mouth of the trap had splints converging inwards, which would prevent the scape of the fish, were controlled by two weirs. A weir, called tatápi, was placed in shallow streams to capture trout, pike and suckers. A row of stakes were placed in the bottom of the stream and stones, logs, stumps and dirt was piled up against the stakes so that the water would be dammed and have to pour over the weir and into a trap on the other side. Another weir, the tafsifschi, was used in a larger stream to catch allis (steelhead trout) when they would return to sea in the fall. The tafsifschi consisted of two fence sections which extended from opposite river banks at a down-stream angle; almost meeting mid-river. They were connected by a short section of wall made by lashing horizontal poles close together across the gap. This was the lowest point in the created dam, and water would pour over carrying the fish into the basket on the other side of the gap.[17] Salmon would be caught by spear, seine, or in nets that hung above water falls or dams.[15]

Hunting

Due to the dry nature of the Achomawi's land, deer was not always abundant, hence their unique way of hunting deer compared to other Californian Natives America.[15] A deep pit would be dug along a deer trail, covered with brush, the trail restored including adding deer tracks using a hoof, and all dirt and human evidence taken away. The settlers' cattle would also fall in these pits, so much so that the settlers convinced the people to stop this practice. The pits were most numerous near the river because the deer came down to drink and so the river is named for these trapping pits.[18] Deer hunting was always preceded by ritual. Rituals also existed that did not involve the hunting process but involved the avoidance of deer meat. Adolescent girls would stuff their nostrils with fragrant herbs to avoid smelling venison being cooked while going through their maturity ceremony.[15]

Waterfowl, like ducks, were snared by a noose stretched across streams. Rabbits would be driven into nets.[15]

Gathering

A variety of foodstuffs was gathered by the Achomawi people throughout the year. Acorns were a staple for Achomawi and other California native societies. Due to a scarcity of oak trees in the Achomawi territories these nuts were largely procured from neighboring cultures.[3][15] Tule was utilized by the Achomawi in creating twine, mats and shoes; in addition to being a food source. Sprouts were gathered in early spring and then cooked or eaten raw. Fruit bearing trees were also a source of nutrition, including the Oregon grape, Oregon plum, Pacific yew, and Whiteleaf manzanita. Other plants harvested annually included camas, in addition to several species of seed bearing grasses, Indian potatoes and lilies. These bulbs and seeds were preserved and stored for use in the winter months in addition for occasional use in trade.[19]

Religion

Adolescent boys sought guardian spirits called tinihowi and both genders experienced puberty ceremonies.[3] A victory dance was also held in the community, which involved the toting of a head of the enemy with women participating in the celebration. Elder men would fast to increase the run of fish and women and children would eat out of sight of the river to encourage fish populations.[12] Spiritual presences were identified with mountain peaks, certain springs, and other sacred places.[20]

Achomawi shamans maintained the health of the community, serving as doctors. Shamans would focus on "pains" which were physical and spiritual. These pains were believed to have been put on people by other, hostile shamans. After curing the pain, the shaman would then swallow it. Both men and women held the role of shaman. A shaman was said to have a fetish called kaku by Kroeber [21] or qaqu by Dixon.[22] Kroeber relied upon Dixon's work in this part of California.[23] (The letter q was supposed to represent a velar spirant x, as in Bach, in the system generally used at that time for writing indigenous American languages.[24] The Achumawi Dictionary[25] does not have this word.) Dixon described the qaqu as a bundle of feathers which were believed to grow in rural places, rooted in the earth, and which, when secured, dripped of blood constantly. It was used as an oracle to locate pains in the body.[22] Quartz crystal was also revered within the community and was obtained by diving into a waterfall. In the pool in the waterfall the diver would find a spirit (like a mermaid) who would lead the diver to a cave where the crystals grew. A giant moth cocoon, which symbolized the "heart of the world", was another fetish, and harder to obtain.[13]

Puberty rites

A girl would begin her puberty ritual by having her ears pierced by her father or another relative. She would then be picked up, dropped, and then hit with an old basket, before running away. During this part, her father would pray to the mountains for her. The girl would return in the evening with a load of wood, another symbol of women's roles within the community, like the basket. She would then build a fire in front of her house and dance around it throughout the night, with relatives participating; around the fire or inside the house. Music would accompany the dance, made by a deer hoof rattle. During the ritual time, she would have herbs stuffed up her nose to avoid smelling venison being cooked. In the morning, she would be picked up and dropped again, and she would run off with the deer hoof rattle. This repeated for five days and nights. On the fifth night, she would return from her run to be sprinkled with fir leaves and bathed, completing the ritual.[26]

Boys’ puberty rites were similar to the girls ritual but adds shamanistic elements. The boys ears are pierced, and then he is hit with a bowstring and runs away to fast and bathe in a lake or spring. While he is gone, his father prays for the mountains and the Deer Woman to watch over the boy. In the morning, he returns, lighting fires during his trip home and eats outside the home and then runs away again. He stays several nights away, lighting fires, piling up stones and drinking through a reed so that his teeth would not come into contact with water. If he sees an animal on the first night in the lake or spring or dream of an animal; that animal would become his personal protector. If the boy has a vision like this, he will become a shaman.[26]

War traditions and weaponry

In general Achomawi held a significantly negative view of actual warfare, finding it be an undesirable outcome. Joining in a battle or killing an enemy was believed to give a particular contamination. Only through "a rigorous program of purification" could an individual remove it.[27] Sinew-backed bows were their primary weapon. These bows had a noticeably flatter design than those used by the Yurok and other California tribes. Body armor would be made of hard elk or bear hide with a waistcoat of thin sticks wrapped together.[11]

Arts

Basket-making

The Achomawi follow in the tradition of other California tribes, with their skills in basketry. Baskets are made of willow and are colored with vegetable dyes.[3] Their basketry is twined, and compared to the work of the Hupa and Yurok are described as being softer, larger, and with designs that lack the focus on one horizontal band. The shapes are similar to those made by the Modoc[11] and have slightly rounded bottoms and sides, wide openings and shallow depth.[17] Baskets sizes and shapes depend on the intended use. Some baskets are created for women to wear as caps, some for cooking on hot stones, holding semi-liquid food or water. Willow rods are used for the warp and pine root is used for the weft. In the caps, only tule fiber is used. A burden basket was also made by the Achomawi, as was a mesh beater which would be used to harvest seeds into the burden baskets, made of willow or a mix of willow and pine root.[17]

Most baskets are covered in a light white overlay of xerophyllum tenax, though it is believed that those covered in xerophyllum tenax are for trade and sale only, not for daily use. The xerophyllum tenax protects the baskets artwork and materials when used, helpful for when boiling or holding water. Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber believed that by 1925 the Achomawi were no longer cooking in baskets, and were merely making them for sale and trade.[11]

Canoes

The Achomawi made simple dugout canoes of pine or cedar. Longer, thinner and less detailed than the Yurok redwood boats and Modoc canoes, the canoes were produced for transportation and hunting.[11]

History

Early history

Relations with the nearby Atsugewi speakers were traditionally favorable for the majority of Achomawi. Yet the close proximity between the Illmawi band of Achomawi and the Atsugewi inhabitants of Hat Creek (haatiiw̓iw), the Atsuge (haatííw̓iwí - ″Hat Creek People″, own name: atuwanúúci), were terse. These bad feelings arose in part from particular Atsuge trespassing upon Illmawi territory while traveling through to collect obsidian from the nearby Glass Mountain (sáttít - ″flint place″, also name for Medicine Lake).[28]

In their networks with neighboring cultures Achomawi exchanged their furs, basketry, steatite, rabbit-skin blankets, food and acorn in return for goods such as epos root, clam beads, obsidian and other goods. Through these commercial dealings goods from the Wintun (iqpiimí - ″Wintun people″, númláákiname - Nomlaki (Central Wintu people)), Modoc and possibly the Paiute (aapʰúy - ″stranger″) were transported by the Achomawi.[15] Eventually they would also trade for horses with the Modoc.[13] The Achomawi used beads for money, specifically dentalia.[15]

Contact between the Achomawi and Atsugewi speakers with the Klamath (ál ámmí - ″Klamath people″) and Modoc (lutw̓áámíʼ / lútʰám - ″Modoc people″) to the north largely wasn't documented. Despite this Garth found it probable that there were extensive interactions between the cultures prior to the adoption of horses by the Northerners.[29] Leslie Spier concluded that the Klamath and their Modoc relatives gained horses in the 1820s.[30] Achomawi settlements became victim to slave raids by Modoc and Klamath horsemen. In particular the residents around Goose Lake, the Hewisedawi, were used by the Goose Lake Modoc (lámmááw̓i - ″Goose Lake Modoc″) "as a source of supply of slaves (cah̓h̓úm - slave; lit. ″dog″- later also meaning ″horse″) who might be traded for other goods."[31] Captured people would be sold into slavery at an intertribal slave market at The Dalles in present-day Oregon.[4][3]

The Madesi band, Achomawi residents around modern Big Bend, had particularly cordial relationships with the Wintun. The nearby Shasta (sástayci / sastííci - ″Shasta people″) and Yana (tʰísayci - ″Yana people″) were "powerful enemies" that would on occasion attack Madesi settlements.[32]

European contact

In 1828 fur trappers and traders visited Achomawi land. It wasn't until the 1840s and the California gold rush when outsiders began to arrive in large numbers and taking land and disturbing the Achomawi lifeways. The Rogue River Wars in 1855-56 brought a strong U.S. military presence to the area, as well.[3]

Late 19th and 20th centuries

In 1871 community members participated in the first Ghost Dance movement, and other future religious revitalization movements after moving to a reservation. In 1921, a smallpox epidemic took its toll on the Achomawi's.[3]

Present day

The majority of Achomawi people are enrolled in the federally recognized Pit River Tribe. The tribe consists of several autonomous bands - nine Achomawi and two (perhaps three) Atsugewi bands:

Upriver Achomawi (Eastern Achomawi)

- h̓ééwíssátééwi (“Highland People”),[33] h̓ééwíssáy̓tuwí (“Goose Lake People”), usually Hewisedawi/Hay-wee-see-daw-wee/Hewise (″Those from On Top″, "The People Who Live High Up"): several Hewise villages were situated around the Goose Lake, their territory stretched from Fandango Valley south through the Warner Mountains to Cedar Pass; west across the Pit River and out onto the high plateau area called Devils Garden; north up to the west side of Goose Lake. Other villages were located in the south of the territory along the Pit River and out on the Devils Garden area; usually referred to as "Goose Lake Achomawi" or "Goose Lake People"

- astaaqííw̓awí, usually Astarawi / Astariwawi; in Atsugewi Astakwaini owte (both: "Hot [Springs] People"): their four settlements were located along the Pit River in the area of Canby, California and the nearby hot springs; usually referred to as "Hot Springs Achomawi" or “Canby People”

- q̓úsyálléq̓tawi, q̓ússiálláq̓tawí, q̓óssi álláq̓tawí, usually Kosealekte/Kosalektawi/Qosalektawi ("Juniper liking People"); in Atsugewi Astakwaini owte ("Hot Springs People"): their three settlements were located in the headwaters of the Pit River southwards to the area of Alturas, California; usually referred to as "Alturas Achomawi"

- h̓ámmááw̓i (“Upriver People", "High Plateau People"), usually Hammawi ("South Fork of Pit River People"); in Atsugewi Apishi: their main village Hamawe/Hammawi was in the vicinity of Likely, California (formerly South Fork) at the South Fork of the Pit River, another eight settlements were also located along the South Fork; usually referred to as "Likely Achomawi"

- atw̓áámi ("Valley People") or atw̓ámsini ("Valley Dwellers"), usually Atuami/Atwamwi or Atwamsini; in Atsugewi Akui owte ("Big Vally People"): their 27 settlements were located along Ash Creek and Pit River in the high country of Big Valley; usually referred to as "Big Valley Achomawi" or “Big Valley People”

Downriver Achomawi (Western Achomawi)

- acúmmááwi (“[Pit] River People”), wannúkyumiʔ (“Fall River People”), usually Ajumawi/Achumawi/Achomawi proper ("River People"); in Atsugewi Dicowi owte (“Fall River People”): their 17 settlements were located along the Fall River and Pit River (acúmmá - "river") up to Fall River Mills, California; usually referred to as "Fall River Achomawi" or “Fall River Mills People”

- ílmááwi (“Canyon People”), usually Ilmawi/Ilmewi/Ilmiwi ("People of the Village of Ilma"); in Atsugewi Apahezarini: occupied 13 settlements along Pit River from the mouth of Burney Creek to a few miles below Fall River Mills; usually referred to as "Cayton Valley Achomawi"

- iic̓áátawí (“Burney Valley People”), usually Itsatawi ("Goose Valley People"); in Atsugewi Bomari owte (“Pit River People”): their 25 settlements centered on the Goose Valley and the lower Burney Creek area; had close ties to the Madesi; usually referred to as “Goose Valley Achomawi”

- matéési, usually Madesi (Mah-day-see/Madessawi)[34] (“People of the Village of Mah-dess' (Big Bend)”, “Madesi Valley People”); in Atsugewi Dakyupeni or Psicamuci (no translation): their territory included Big Bend and its Hot Springs and the surrounding area of the Lower Pit River (Ah-choo'-mah in the Madesi dialect), and several of its tributaries, such as Kosk Creek (An-noo-che'che) and Nelson Creek (Ah-lis'choo'-chah). Their main village Mah-dess' or Mah-dess' Atjwam (″Madesi Valley″) was on the north bank of the Pit River, east of Kosk Creek, and was directly across the river from the smaller villages that surrounded the hot springs on the river's south bank, which were called Oo-le'-moo-me, Lah'-lah-pis'-mah, and Al-loo-satch-ha.; usually referred to as "Big Bend Achomawi" or “Big Bend People”, sometimes as “Montgomery Creek People”[35]

and the two (perhaps three?) Atsugewi bands[36]

- haatííw̓iwí; in Atsugewi Atuwanúúci (both: “Hat Creek People”), usually Atsugewi; in Atsugewi Atsugé (both: "Pine-tree People"): their five settlements were mainly along Hat Creek between Mount Lassen and the Pit River as well as along Burney Creek (the families settling there are sometimes considered a separate Wamari'i / Wamari'l band); usually referred to as “Hat Creek Indians” or “Pine Tree Tribe”

- ammítci (“People of Ammít, i.e. Dixie Valley”), usually Apwarugewi; in Atsugewi Aporige / Apwaruge ("People of Apwariwa, i.e. Dixie Valley") or Mahuopani ("Juniper-tree People"): their 12 settlements were located along Beaver Creek, Pine Creek, Willow Creek, Susan River and on the shores of Eagle Lake and Horse Lake, but their main settlement area was along Horse Creek in Little Valley and Dixie Valley; usually referred to as “Horse Creek Indians” or "Dixie Valley Tribe"Willow Creek (Lassen County, California)

- wanúmcíw̓awí; in Atsugewi Wamari'i / Wamari'l (both: "Burney Valley People"): their settlements were located along the Burney Creek up to its confluence with the Pit River (mostly counted among the Atsugewi band)); usually referred to as “Hat Creek Indians” or “Pine Tree Tribe”

that since time immemorial have resided in the area known as the 100-mile (160 km) square, located in parts of Shasta, Siskiyou, Modoc, and Lassen counties in the state of California.[37]

There is a Housing Authority that through Government grants has developed community housing projects, such as housing for low income families and elders. The Tribe operates a Day Care center, and environmental program. The Pit River Tribe currently operates Pit River Casino, a Class III gaming facility located on 79 acres (320,000 m2) in Burney, California.

Today there are around 1,800 tribal members enrolled in contemporary Achumawi federally recognized tribes, that are as follows:

- Pit River Tribe (Achomawi bands: Ajumawi, Astarawi, Atwamsini, Hammawi, Hewisedawi, Ilmawi, Itsatawi, Kosalektawi, and Madesi, Atsugewi bands: Atsuge and Aporige)

- Alturas Indian Rancheria[3] (Achomawi name: q̓ússiálláq̓tawí / q̓óssi álláq̓tawí - "Kosealekte/Kosalektawi/Qosalektawi" or "Alturas/Altʰúúlas Achomawi"; Population: 0 living on rancheria)

- Big Bend Rancheria[3] (Achomawi name: matéési - "Madesi (Mah-day-see/Madessawi)" or "Big Bend Achomawi"; Population: 5 living on rancheria)

- Likely Rancheria[3] (Achomawi name: h̓ámmááw̓i - "Hammawi" or "Likely Achomawi"; Population: 0 living on rancheria)

- Lookout Rancheria[3] (Population: 21 living on rancheria)

- Montgomery Creek Rancheria[3] (Achomawi name: íípʰuníw̓ca or íípʰuunídial/íípʰuurí - "Madesi (Mah-day-see/Madessawi)" or "Montgomery Creek [Achomawi]"; Population: 4 living on rancheria)

The following rancherias are shared with other communities:

- Redding Rancheria (Wintu, Achomawi bands, and Yana; Population: 24 living on rancheria)

- Roaring Creek Rancheria.[3][38] (Achomawi and Atsugewi bands; Population: 18 living on rancheria)

- Susanville Indian Rancheria[3] (Washoe, Achomawi, Mountain Maidu, Northern Paiute, and Atsugewi; Population: 1,272 with 342 living on rancheria)

- XL Ranch[3] (Achomawi and Atsugewi bands, and some Northern Paiute; Population: 62 living on rancheria)

- Big Valley Rancheria (Achomawi name: atw̓áámi / atw̓ámsini - "Atwamsini (Atuami/Atwamwi)" or "Big Valley Achomawi"; Xa-Ben-Na-Po Band of Eastern (Clear Lake) Pomo and Achomawi; Population: 168 living on rancheria)

- Round Valley Indian Tribes (Yuki, Konkow Maidu, Mitoám Kai (Little Lake) Pomo and other Pomo bands, Nomlaki (Central Wintu), Cahto, Wailaki, and Achomawi; Population: 68 living on rancheria)

- Lytton Band of Pomo Indians (Achomawi, Nomlaki, and Gualála (Ahkhawalalee) Pomo; Population: 0 living on rancheria)

- Picayune Rancheria (Chukchansi Yokuts, Pomo, and approximately 60 other tribes; Population: 65 living on rancheria.)

References

- Nevin, Bruce E. (1998), "Aspects of Pit River phonology" (PDF), Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania

- Merriam, C. Hart, The Classification and Distribution of The Pit River Indian Tribes of California. Smithsonian Institution (Publication 2874), Volume 78, Number 3, 1926

- Waldman 2006, pp. 2–3.

- Kroeber 1925, p. 308.

- Kniffen 1928, p. 318.

- Garth 1953, p. 177.

- Curtis 1924, p. 135.

- "ACHOMAWI". Four Directions Institute. 2007. Archived from the original on February 14, 2002. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Mithun 1999:470-472

- Golla 2011, pp. 84–111.

- Kroeber 1925, p. 310.

- Kroeber 1925, p. 313.

- San Francisco State University 2011.

- "Subsistence". Achumawi. College of the Siskiyous. Archived from the original on 8 November 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Kroeber 1925, p. 309.

- Curtis 1924, p. 136.

- Curtis 1924, p. 137.

- Stephen Powers * Tribes of California*, p. 269 (Regents of the University of California, foreword by R. Heizer, 1976)

- Kniffen 1928, p. 301.

- Merriam identified the character Annikadel with God in a collection of stories, although his interactions with other characters contradict that idea. Woiche, Istet (1992). Annikadel: The history of the universe as told by the Achumawi ndians of California (Reprint ed.). Tucson: University of Arizona Press. p. 4. ISBN 0-8165-1283-3.

- Kroeber 1925, p. 315.

- Dixon 1904, pp. 24–25.

- Golla 2011, pp. 38–39.

- Powell, John Wesley (1880). Introduction to the study of Indian languages with words, phrases and sentences to be collected (2nd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. pp. 9.

- Olmsted, David L. Achumawi Dictionary. University of California Publications in Linguistics. Vol. 45. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Kroeber 1925, p. 314.

- Garth 1953, p. 182.

- Kniffen 1928, pp. 313, 316.

- Garth 1953, p. 185.

- Spier 1930, p. 31.

- Kniffen 1928, p. 309.

- Kniffen 1928, p. 314.

- Achomawi dictionary

- Big Bend Hot Springs Project - Pit River Native Indigenous Languages

- Big Bend Hot Springs Project - Big Bend and Big Bend Hot Springs History

- Thomas R. Garth - ATSUGEWI ETHNOGRAPHY

- Pit River Docket No. 347, (7 ICC 815 at 844), Indian Claims Commission; see also Olmsted and Stewart 1978:226.

- "California Indians and Their Reservations." Archived 2010-07-26 at the Wayback Machine San Diego State University Library and Information Access. 2009 (retrieved 15 Dec 2009)

Bibliography

- Curtis, Edward S. (1924), The North American Indian. Volume 13 - The Hupa. The Yurok. The Karok. The Wiyot. Tolowa and Tututni. The Shasta. The Achomawi. The Klamath., North American Indian, vol. 13, Classic Books Company, ISBN 978-0-7426-9813-0, retrieved 21 November 2011

- Dixon, Roland B. (1904). "Some Shamans of Northern California". Journal of American Folklore. Bloomington, IN: American Folklore Society. 17 (64): 23–27. doi:10.2307/533984. JSTOR 533984.

- Golla, Victor (2011), California Indian Languages, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-26667-4

- Garth, Thomas R. (1953), Atsugewi Ethnography, Anthropological Records, vol. 14, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, pp. 129–212

- Kniffen, Fred B. (1928), Achomawi Geography, University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. 23, University of California Press, pp. 297–332

- Kroeber, Alfred Louis (1925), Handbook of the Indians of California, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, retrieved 28 January 2018

- San Francisco State University, Encyclopedia of Native American tribes, archived from the original on 19 October 2011, retrieved 20 November 2011

- Spier, Leslie (1930), Kroeber, Alfred L.; Lowie, Robert (eds.), Klamath Ethnography, University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology, vol. 30, University of California Press, pp. 1–338

- Waldman, Carl (September 2006), Encyclopedia of Native American tribes, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-6274-4, retrieved 21 November 2011

Further reading

- Evans, Nancy H., 1994. "Pit River," in Native America in the Twentieth Century: An Encyclopedia, ed. Mary B. Davis (NY: Garland Pub. Co).

- Garth, T. R. 1978. "Atsugewi". In California, edited by Robert F. Heizer, pp. 236–243. Handbook of North American Indians, William C. Sturtevant, general editor, vol. 8. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Jaimes, M. Annette, 1987. "The Pit River Indian Claim Dispute in Northern California," Journal of Ethnic Studies, 14(4): 47–74.

- Mithun, Marianne. 1999. The Languages of Native North America. Cambridge University Press.

- Olmsted, D.L. and Omer C. Stewart. 1978. "Achumawi" in Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 8 (California), pp. 225–235. William C. Sturtevant, and Robert F. Heizer, eds. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 0-16-004578-9/0160045754.

- Tiller, Veronica E. Velarde, 1996. Tiller's Guide to Indian Country (Albuquerque: BowArrow Pub. Co.): see X-L Ranch Reservation, pp. 308–09. There is a new later edition, 2005.

External links

- Official website of the Pit River Tribe

- A bibliography for the Achomawi from Shasta Public Libraries

- Achomawi Bibliography, from California Indian Library Collections Project