Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty (Spanish: Tratado de Adams-Onís) of 1819,[1] also known as the Transcontinental Treaty,[2] the Spanish Cession,[3] the Florida Purchase Treaty,[4] or the Florida Treaty,[5][6] was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined the boundary between the U.S. and Mexico (New Spain). It settled a standing border dispute between the two countries and was considered a triumph of American diplomacy. It came during the successful Latin American wars of independence against Spain.

| Treaty of Amity, Settlement and Limits between the United States of America, and His Catholic Majesty | |

|---|---|

Map showing results of the Adams–Onís Treaty. | |

| Type | Bilateral treaty |

| Context | Territorial cession |

| Signed | February 22, 1819 |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Effective | February 22, 1821 |

| Expiry | April 14, 1903 |

| Parties | |

| Citations | 8 Stat. 252; TS 327; 11 Bevans 528; 3 Miller 3 |

| Languages | English, Spanish |

| Terminated by the treaty of friendship and general relations of July 3, 1902 (33 Stat. 2105; TS 422; 11 Bevans 628). | |

Florida had become a burden to Spain, which could not afford to send settlers or man garrisons, so Madrid decided to cede the territory to the United States in exchange for settling the boundary dispute along the Sabine River in Spanish Texas. The treaty established the boundary of U.S. territory and claims through the Rocky Mountains and west to the Pacific Ocean, in exchange for Washington paying residents' claims against the Spanish government up to a total of $5 million Spanish dollars[7]and relinquishing the U.S. claims on parts of Spanish Texas west of the Sabine River and other Spanish areas, under the terms of the Louisiana Purchase.

The treaty remained in full effect for only 183 days: from February 22, 1821, to August 24, 1821, when Spanish military officials signed the Treaty of Córdoba acknowledging the independence of Mexico; Spain repudiated that treaty, but Mexico effectively took control of Spain's former colony. The Treaty of Limits between Mexico and the United States, signed in 1828 and effective in 1832, recognized the border defined by the Adams–Onís Treaty as the boundary between the two nations.

History

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

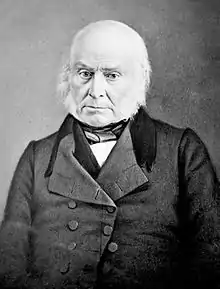

6th President of the United States

Presidential campaigns

Post-presidency

|

||

The Adams–Onís Treaty was negotiated by John Quincy Adams, the Secretary of State under U.S. President James Monroe, and the Spanish "minister plenipotentiary" (diplomatic envoy) Luis de Onís y González-Vara, during the reign of King Ferdinand VII.[8]

Florida

Spain had long rejected repeated American efforts to purchase Florida. But by 1818, Spain was facing a troubling colonial situation in which the cession of Florida made sense. Spain had been exhausted by the Peninsular War (1807–1814) against Napoleon in Europe and needed to rebuild its credibility and presence in its colonies. Revolutionaries in Central America and South America had been waging wars of independence since 1810. Spain was unwilling to invest further in Florida, encroached on by American settlers, and it worried about the border between New Spain (a large area including today's Mexico, Central America, and much of the current U.S. western states) and the United States. With minor military presence in Florida, Spain was not able to restrain the Seminole warriors who routinely crossed the border and raided American villages and farms, as well as protected southern slave refugees from slave owners and traders of the southern United States.[9]

The United States from 1810 to 1813 annexed and then invaded most of West Florida (already independent as the Republic of West Florida west of the Pearl River) up to the Perdido River (modern border river between the states of Alabama and Florida), claiming that the Louisiana Purchase covered West Florida also.[10] General James Wilkinson invaded and occupied Mobile during the War of 1812 and the Spanish never returned to West Florida west of the Perdido River.

The State of Muskogee (1799-1803) demonstrated Spain's inability to control the interior of East Florida, at least de facto; the Spanish presence had been reduced to the capital (San Agustín) and other coastal cities, while the interior belonged to the Seminole nation.

While fighting escaped African-American slaves, outlaws, and Native Americans in U.S.-controlled Georgia during the First Seminole War, American General Andrew Jackson had pursued them into Spanish Florida. He built Fort Scott, at the southern border of Georgia (i.e., the U.S.), and used it to destroy the Negro Fort in northwest Florida, whose existence was perceived as an intolerably disruptive risk by Georgia plantation owners.

To stop the Seminole based in East Florida from raiding Georgia settlements and offering havens for runaway slaves, the U.S. Army led increasingly frequent incursions into Spanish territory. This included the 1817–1818 campaign by Andrew Jackson that became known as the First Seminole War, after which the U.S. effectively seized control of Florida; albeit for purposes of lawful government and administration in Georgia and not for the outright annexation of territory for the U.S. Adams said the U.S. had to take control because Florida (along the border of Georgia and Alabama Territory) had become "a derelict open to the occupancy of every enemy, civilized or savage, of the United States, and serving no other earthly purpose than as a post of annoyance to them".[11][12] Spain asked for British intervention, but London declined to assist Spain in the negotiations. Some of President Monroe's cabinet demanded Jackson's immediate dismissal for invading Florida, but Adams realized that his success had given the U.S. a favorable diplomatic position. Adams was able to negotiate very favorable terms.[9]

Louisiana

In 1521, the Spanish Empire created the Virreinato de Nueva España (Viceroyalty of New Spain) to govern its conquests in the Caribbean, North America, and later the Pacific Ocean. In 1682, La Salle claimed Louisiana for France.[13] For the Spanish Empire, this was an intrusion into the northeastern frontier of New Spain. In 1691, Spain created the Province of Tejas in an attempt to inhibit French settlement west of the Mississippi River. Fearing the loss of his American territories in the Seven Years' War, King Louis XV of France ceded Louisiana to King Charles III of Spain with the secret Treaty of Fontainebleau in 1762. The Treaty of Paris of 1763 split Louisiana with the portion east of the Mississippi River (except for Île d'Orléans) becoming a part of British North America and the portion west of the river becoming the District of Louisiana within New Spain. This eliminated the French threat, and the Spanish provinces of Luisiana, Tejas, and Santa Fe de Nuevo México coexisted with only loosely defined borders. In 1800, French First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte forced King Charles IV of Spain to cede Louisiana to France with the secret Third Treaty of San Ildefonso. Spain continued to administer Louisiana until 1802 when Spain publicly transferred the district to France. The following year, Napoleon sold the territory to the United States to raise money for his military campaigns.[14]

The United States and the Spanish Empire disagreed over the territorial boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. The United States maintained the claim of France that Louisiana included the Mississippi River and "all lands whose waters flow to it". To the west of New Orleans, the United States assumed the French claim to all land east and north of either the Sabine River[15] or the Rio Grande.[16][17][notes 1] Spain maintained that all land west of the Calcasieu River and south of the Arkansas River belonged to Tejas and Santa Fe de Nuevo México.[18][19][20]

Oregon Country

The British government claimed the region west of the Continental Divide between the undefined borders of Alta California and Russian Alaska on the basis of (1) the third voyage of James Cook in 1778, (2) the Vancouver Expedition in 1791–1795, (3) the solo journey of Alexander Mackenzie to the North Bentinck Arm[notes 2] in 1792–1793, and (4) the exploration of David Thompson in 1807–1812. The Third Nootka Convention of 1794 stipulated that both the British and Spanish would abandon any settlements they had in the Nootka Sound.[21]

The United States claimed essentially the same region on the basis of (1) the voyage of Robert Gray up the Columbia River in 1792, (2) the United States Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804–1806, and (3) the establishment of Fort Astoria[notes 3] on the Columbia River in 1811. On 20 October 1818, the Anglo-American Convention of 1818 was signed setting the border between British North America and the United States east of the Continental Divide along the 49th parallel north and calling for joint Anglo-American occupancy west of the Great Divide. The Anglo-American Convention ignored the Nootka Convention of 1794 which gave Spain joint rights in the region. The convention also ignored Russian settlements in the region. The U.S. government referred to this region as the Oregon Country, while the British government referred to the region as the Columbia District.[22]

Russian America

.jpg.webp)

On 16 July 1741, the crew of the Imperial Russian Navy ship Saint Peter (Святой Пётр), captained by Vitus Bering, sighted Mount Saint Elias,[notes 4] the fourth-highest summit in North America. While dispatched on the Russian Great Northern Expedition, they became the first Europeans to land in northwestern North America. The Russian fur trade soon followed the discovery. By 1812, the Russian Empire claimed Alaska and the Pacific Coast of North America as far south as the Russian settlement of Fortress Ross,[notes 5] only 105 kilometers (65 miles) northwest of the Spain's Presidio Real de San Francisco.[23]

New Spain

.png.webp)

.png.webp)

The Spanish Empire claimed all lands west of the Continental Divide throughout the Americas.[notes 6] Between 1774 and 1779, King Charles III of Spain ordered three naval expeditions north along the Pacific Coast to assert Spain's territorial claims. In July 1774, Juan José Pérez Hernández reached latitude 54°40′ north off the northwestern tip of Langara Island before being forced to turn south. On 15 August 1775, Juan Francisco de la Bodega y Quadra reached the latitude 59°0′ before returning south. On 23 July 1779, Ignacio de Arteaga y Bazán and Bodega y Quadra reached Puerto de Santiago on Isla de la Magdalena (now Port Etches on Hinchinbrook Island)[notes 7] where they held a formal possession ceremony commemorating Saint James, the patron saint of Spain. This marked the northernmost Spanish exploration in the Pacific Ocean.

Between 1788 and 1793, Spain launched several more expeditions north of Alta California. On 24 June 1789, Esteban José Martínez Fernández y Martínez de la Sierra established the Spanish colony of Santa Cruz de Nuca[notes 8] on the northwest coast of Vancouver Island. Asserting Spain's claim of exclusive sovereignty and navigation rights, Martínez seized several ships in Nootka Sound provoking the Nootka Crisis with Great Britain. In negotiations to resolve the crisis, Spain claimed that its Nootka Territory extended north from Alta California to the 61st parallel north and from the Continental Divide west to the 147th meridian west. On 11 January 1794, the Spanish and British governments signed the Third Nootka Convention which called for the abandonment of all permanent settlements on Nootka Sound. Santa Cruz de Nuca was formally abandoned on 28 March 1795. The convention also stipulated that both nations were free to use Nootka Sound as a port and erect temporary structures, but, "neither ... shall form any permanent establishment in the said port or claim any right of sovereignty or territorial dominion there to the exclusion of the other. And Their said Majesties will mutually aid each other to maintain for their subjects free access to the port of Nootka against any other nation which may attempt to establish there any sovereignty or dominion".[21] On 19 August 1796, Spain made the decision to join the French Republic in their war against Great Britain with the signing of the Second Treaty of San Ildefonso, thus ending Spanish and British cooperation in the Americas.

East of the Continental Divide, the Spanish Empire claimed all land south of the Arkansas River[20] that was west of the Calcasieu River.[18][notes 9] The vast disputed region between the territorial claims of the United States and Spain was occupied primarily by native peoples with very few traders of either Spain or the United States present. In the south, the disputed region between the Calcasieu River and the Sabine River encompassed Los Adaes, the first capital of Spanish Texas. The region between the Calcasieu and Sabine rivers became a lawless no man's land. The United States saw great potential in these western lands, and hoped to settle their borders. Spain, seeing the end of New Spain, hoped to employ its territorial claims before it would be forced to grant Mexico its independence (later in 1821). Spain hoped to regain much of its territory after the regional demands for independence subsided.

Details of the treaty

The treaty, consisting of 16 articles[24] was signed in Adams' State Department office at Washington,[25] on February 22, 1819, by John Quincy Adams, U.S. Secretary of State, and Luis de Onís, Spanish minister. Ratification was postponed for two years, because Spain wanted to use the treaty as an incentive to keep the United States from giving diplomatic support to the revolutionaries in South America. On February 24, the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty unanimously,[26] but because of Spain's stalling, a new ratification was necessary and this time there were objections. Henry Clay and other Western spokesmen demanded that Spain also give up Texas. This proposal was defeated by the Senate, which ratified the treaty a second time on February 19, 1821, following ratification by Spain on October 24, 1820. Ratifications were exchanged three days later and the treaty was proclaimed on February 22, 1821, two years after the signing.[27]

The Treaty closed the first era of United States expansion by providing for the cession of East Florida under Article 2; the abandonment of the controversy over West Florida under Article 2 (a portion of which had been seized by the United States); and the definition of a boundary with New Spain, that clearly made Texas a part of it, under Article 3, thus ending much of the vagueness in the boundary of the Louisiana Purchase. Spain also ceded to the U.S. its claims to the Oregon Country, under Article 3.

The U.S. did not pay Spain for Florida, but instead agreed to pay the legal claims of American citizens against Spain, to a maximum of $5 million, under Article 11.[notes 10] Under Article 12, Pinckney's Treaty of 1795 between the U.S. and Spain was to remain in force. Under Article 15, Spanish goods received exclusive most-favored-nation privileges in the ports at Pensacola and St. Augustine for twelve years.

Under Article 2, the U.S. received ownership of Spanish Florida. Under Article 3, the U.S. relinquished its own claims on parts of Texas west of the Sabine River and other Spanish areas.

Border

Article 3 of the treaty states:

The Boundary Line between the two Countries, West of the Mississippi, shall begin on the Gulf of Mexico, at the mouth of the River Sabine in the Sea (29°40′42″N 93°50′03″W), continuing North, along the Western Bank of that River, to the 32d degree of Latitude (32°00′00″N 94°02′45″W); thence by a Line due North to the degree of Latitude, where it strikes the Rio Roxo of Nachitoches, or Red-River (33°33′04″N 94°02′45″W), then following the course of the Rio-Roxo Westward to the degree of Longitude, 100 West from London and 23 from Washington (34°33′37″N 100°00′00″W), then crossing the said Red-River, and running thence by a Line due North to the River Arkansas (37°44′38″N 100°00′00″W), thence, following the Course of the Southern bank of the Arkansas to its source in Latitude, 42. North and thence by that parallel of Latitude to the South-Sea [Pacific Ocean]. The whole being as laid down in Melishe's Map of the United States, published at Philadelphia, improved to the first of January 1818. But if the Source of the Arkansas River shall be found to fall North or South of Latitude 42, then the Line shall run from the said Source (39°15′30″N 106°20′38″W) due South or North, as the case may be, till it meets the said Parallel of Latitude 42 (42°00′00″N 106°20′38″W), and thence along the said Parallel to the South Sea (42°00′00″N 124°12′46″W).

At the time the treaty was signed, the course of the Sabine River, Red River, and Arkansas River had only been partially charted. Furthermore, the rivers changed course periodically. It would take many years before the location of the border would be fully determined.

South of the 32nd parallel north, the Spanish Empire and the United States settled for the U.S. claim along the Sabine River. Between the meridians 94°2′45" and 100° west, the parties settled on the Spanish claim along the Red River. West of the 100th meridian west, the parties settled on the Spanish claim along the Arkansas River. From the source of the Arkansas River in the Rocky Mountains, the parties settled on a border due north along that meridian (106°20′37″W) to the 42nd parallel north, thence west along the 42nd parallel to the Pacific Ocean.

Spain won substantial buffer zones around its provinces of Tejas, Santa Fe de Nuevo México, and Alta California in New Spain. While the United States relinquished substantial territory east of Continental Divide, the newly defined border allowed settlement of the southwestern part of the State of Louisiana, the Arkansas Territory, and the Missouri Territory.

Spain relinquished all claims in the Americas north of the 42nd parallel north. This was a historic retreat in its 327-year pursuit of lands in the Americas. The previous Anglo-American Convention of 1818 meant that both American and British citizens could settle land north of the 42nd parallel and west of the Continental Divide. The United States now had a firm foothold on the Pacific Coast and could commence settlement of the jointly occupied Oregon Country (known as the Columbia District to the British government). The Russian Empire also claimed this entire region as part of Russian America.[23]

For the United States, this Treaty (and the Treaty of 1818 with Britain agreeing to joint control of the Pacific Northwest) meant that its claimed territory now extended far west from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean. For Spain, it meant that it kept its colony of Texas and also kept a buffer zone between its colonies in California and New Mexico and the U.S. territories. Many historians consider the Treaty to be a great achievement for the U.S., as time validated Adams's vision that it would allow the U.S. to open trade with the Orient across the Pacific.[28]

Informally this new border has been called the "Step Boundary", although the step-like shape of the boundary was not apparent for several decades—the source of the Arkansas, believed to be near the 42nd parallel north, was not known until John C. Frémont located it in the 1840s, hundreds of miles south of the 42nd parallel.

Implementation

Washington set up a commission, 1821 to 1824, that handled American claims against Spain. Many notable lawyers, including Daniel Webster and William Wirt, represented claimants before the commission. Dr. Tobias Watkins served as secretary.[29] During its term, the commission examined 1,859 claims arising from over 720 spoliation incidents, and distributed the $5 million in a basically fair manner.[30] The treaty reduced tensions with Spain (and after 1821 Mexico), and allowed budget cutters in Congress to reduce the army budget and reject the plans to modernize and expand the army proposed by Secretary of War John C. Calhoun. The treaty was honored by both sides, although inaccurate maps from the treaty meant that the boundary between Texas and Oklahoma remained unclear for most of the 19th century.

Later developments

The treaty was ratified by Spain in 1820, and by the United States in 1821 (during the time that Spain and Mexico were engaged in the prolonged Mexican War of Independence). Luis de Onís published a 152-page memoir on the diplomatic negotiation in 1820, which was translated from Spanish to English by US diplomatic commission secretary, Tobias Watkins in 1821.[31]

Spain finally recognized the independence of Mexico with the Treaty of Córdoba signed on August 24, 1821. While Mexico was not initially a party to the Adams–Onís Treaty, in 1831 Mexico ratified the treaty by agreeing to the 1828 Treaty of Limits with the U.S.[32]

With the Russo-American Treaty of 1824, the Russian Empire ceded its claims south of parallel 54°40′ north to the United States. With the Treaty of Saint Petersburg in 1825, Russia set the southern border of Alaska on the same parallel in exchange for the Russian right to trade south of that border and the British right to navigate north of that border. This set the absolute limits of the Oregon Country/Columbia District between the 42nd parallel north and the parallel 54°40′ north west of the Continental Divide.

By the mid-1830s, a controversy developed regarding the border with Texas, during which the United States demonstrated that the Sabine and Neches rivers had been switched on maps, moving the frontier in favor of Mexico. As a consequence, the eastern boundary of Texas was not firmly established until the independence of the Republic of Texas in 1836. It was not agreed upon by the United States and Mexico until the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848, which concluded the Mexican–American War. That treaty also formalized the cession by Mexico of Alta California and today's American Southwest, except for the territory of the later Gadsden Purchase of 1854.[33]

Another dispute occurred after Texas joined the Union. The treaty stated that the boundary between the French claims on the north and the Spanish claims on the south was Rio Roxo de Natchitoches (Red River) until it reached the 100th meridian, as noted on the John Melish map of 1818. But, the 100th meridian on the Melish map was marked some 90 miles (140 km) east of the true 100th meridian, and the Red River forked about 50 miles (80 km) east of the 100th meridian. Texas claimed the land south of the North Fork, and the United States claimed the land north of the South Fork (later called the Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River). In 1860, Texas organized the area as Greer County. The matter was not settled until a United States Supreme Court ruling in 1896 upheld federal claims to the territory, after which it was added to the Oklahoma Territory.[34]

The treaty gave rise to a later border dispute between the states of Oregon and California, which remains unresolved. Upon statehood in 1850, California established the 42nd parallel as its constitutional de jure border as it had existed since 1819 when the territory was part of Spanish Mexico. In an 1868–1870 border survey following the admission of Oregon as a state, errors were made in demarcating and marking the Oregon-California border, creating a dispute that continues to this day.[35][36][37][38]

In 2020, a hoax appeared in Spain according to which, in 2055, the Adams–Onís Treaty would expire and Florida would be returned to Spain by the United States, which is false.[39][40]

See also

Footnotes

- At the time of the treaty negotiations, the exploration of the western Mississippi River Basin had only begun. A modern definition of the border initially claimed by the United States begins at the mouth of Sabine Pass on the Gulf of Mexico (29°40′42″N 93°50′03″W), thence up the Sabine River to its source (33°19′16″N 96°12′58″W), thence due north (a distance of about 400 meters (1,300 ft) along meridian 96°12'58"W) to the southern extent of the Red River drainage basin (33°19′29″N 96°12′57″W), thence westward along the southern extent of the Red River drainage basin to the tripoint of the Red River, Arkansas River, and Brazos River drainage basins (34°42′11″N 103°39′37″W), thence northwestward along the southern extent of the Arkansas River drainage basin to the tripoint of the Mississippi River, Colorado River, and San Luis drainage basins (38°20′51″N 106°15′10″W), thence northward along the Continental Divide of the Americas to the tripoint of the Mississippi River, Colorado River, and Columbia River drainage basins (on Three Waters Mountain) (43°23′12″N 109°46′57″W). At this tripoint, the United States claim to the Oregon Country began (see #Oregon Country.)

- 52°22′43″N 127°28′14″W

- 46°11′18″N 123°49′39″W

- 60°17′38″N 140°55′44″W

- 38°30′51″N 123°14′37″W

- The claim of Spain to all lands west of the Continental Divide in the Americas dated to the papal bull Inter caetera issued by Pope Alexander VI on May 4, 1493, which granted to the Crowns of Castile and Aragon the rights to colonize all "pagan lands" 100 leagues west of the Azores and south of the Cabo Verde islands. This edict was superseded by the Treaty of Tordesillas signed on June 7, 1494, which divided the Earth into hemispheres along a meridian 370 leagues west of the Cabo Verde islands. In 1513, explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa claimed the entire "Mar de Sur" (Pacific Ocean) and all lands adjacent for the Crowns of Castile and Aragon.

- 60°19′49″N 146°36′16″W

- 49°35′30″N 126°36′56″W

- At the time of the treaty negotiations, the course of the Calcasieu, Red and Arkansas Rivers were only partially known and the location of the Continental Divide was yet to be determined. A modern definition of the border initially claimed by Spain begins at the mouth of Calcasieu Pass on the Gulf of Mexico (29°45′41″N 93°20′39″W), thence up the Calcasieu River to its source (31°15′56″N 93°12′47″W), thence due north (along meridian 93°12'47"W) to the Red River (31°53′34″N 93°12′47″W), thence up the Red River to the meridian (99°15′19″W) of the source of the Medina River (34°22′20″N 99°15′19″W), thence due north along that meridian (99°15′19″W) to the Arkansas River (38°03′10″N 99°15′19″W), thence up the Arkansas River to its source (39°15′30″N 106°20′37″W), thence due west (a distance of about 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) along the parallel 39°15'30"N) to the Continental Divide (39°15′30″N 106°28′58″W), thence northward along the Continental Divide presumably all the way to the Bering Strait.

- The U.S. commission established to adjudicate claims considered some 1,800 claims and agreed that they were collectively worth $5,454,545.13. Since the treaty limited the payment of claims to $5 million, the commission reduced the amount paid out proportionately by 8⅓ percent.

References

- Crutchfield, James A.; Moutlon, Candy; Del Bene, Terry (2015-03-26). The Settlement of America: An Encyclopedia of Westward Expansion from Jamestown to the Closing of the Frontier. Routledge. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-317-45461-8.

The formal name of the agreement is Treaty of Amity, Settlement, and Limits Between the United States of America and His Catholic Majesty.

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Military and Diplomatic History. OUP USA. January 31, 2013. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-19-975925-5.

- "West Florida (Spanish Cession) 1819". www.arcgis.com. Retrieved 2023-03-01.

- Danver, Steven L. (May 14, 2013). Encyclopedia of Politics of the American West. SAGE Publications. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-4522-7606-9.

- Weeks, p.168.

- A History of British Columbia, p. 90, E.O.S. Scholefield, British Columbia Historical Association, Vancouver, British Columbia 1913

- at artificial parity of 1 to 1 to the scarce and with less silver content US dollar

- Weeks, pp. 170–175.

- Weeks

- Marshall (1914), p. 11.

- John Quincy Adams (1916). Writings of John Quincy Adams, Volumes 1–7. Macmillan. p. 488.

- Alexander Deconde, A History of American Foreign Policy (1963) p. 127

- On April 9, 1682, René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle claimed the Mississippi River and "all lands whose waters flow to it" for King Louis XIV of France. La Salle named the region La Louisiane in honor of the king.

- Marshall (1914), p. 7.

- Marshall (1914), p. 10.

- Marshall (1914), p. 13. "The idea that the Louisiana Purchase extended to the Rio Grande became a certainty with Jefferson early in 1804."

- Hämäläinen, Pekka (2008), The Comanche Empire, New Haven: Yale University Press, p. 156, ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9

- LeJeune, Keagan. "Western Louisiana's Neutral Strip: Its History, People, And Legends". Folklife in Louisiana. Retrieved 2022-04-11.

- Cox, Isaac J. (October 1902). The Southwest Boundary of Texas. Quarterly of the Texas State Historical Association. p. 86.

- José Caballero (1817). "Provincias Internas" (Map). Plano de las Provincias Internas de Nueva España [Plan of the Internal Provinces of New Spain] (in Spanish). Real Academia de la Historia.

- Carlos Calvo, Recueil complet des traités, conventions, capitulations, armistices et autres actes diplomatiques de tous les états de l'Amérique latine, Tome IIIe, Paris, Durand, 1862, pp.366-368.

- Meinig, D.W. (1995) [1968]. The Great Columbia Plain (Weyerhaeuser Environmental Classic ed.). University of Washington Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-295-97485-0.

- Mancini, Mark (4 January 2020). "The Forgotten History of Russia's California Colony".

- "Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819". Sons of Dewitt Colony. TexasTexas A&M University. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015.

- Adams, John Quincy. "Diary of John Quincy Adams". Massachusetts Historical Society. p. 44.

- Marshall (1914), p. 63.

- Deconde, History of American Foreign Policy, p 128

- Jones, Howard (2009). Crucible of Power: A History of American Foreign Relations to 1913. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-7425-6453-4.

- Neal, John (1869). Wandering Recollections of a Somewhat Busy Life. Boston, Massachusetts: Roberts Brothers. p. 209.

- Cash, Peter Arnold (1999), "The Adams–Onís Treaty Claims Commission: Spoliation and Diplomacy, 1795–1824", DAI, PhD dissertation U. of Memphis 1998, vol. 59, no. 9, pp. 3611–A. DA9905078 Fulltext: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses.

- Onís, Luis de (1821) [Originally published in Spanish in 1820 in Madrid, Spain]. Memoir Upon the Negotiations Between Spain and the United States of America, Which Led to the Treaty of 1819. Translated by Watkins, Tobias. Washington, D.C.: E. De Krafft, Printer. p. 3.

- The Border: Adams–Onís Treaty, PBS

- Brooks (1939) ch 6

- Meadows, William C. (January 1, 2010). Kiowa Ethnogeography. University of Texas Press. p. 193. ISBN 9780292778443. Retrieved February 21, 2017.

- Barnard, Jeff (May 19, 1985). "California–Oregon Dispute: Border Fight Has Townfolk on Edge". Los Angeles Times.

Preliminary studies indicate that, as the result of an 1870 surveying error, Oregon has about 31,000 acres of California, while California has about 20,000 acres of Oregon.

- Turner, Wallace (March 24, 1985). "SEA RICHES SPUR FEUD ON BORDER". New York Times.

The border should follow the 42d parallel straight west from the 120th meridian to the Pacific. Instead it zigzags, and only one of the many surveyor's markers put down in 1868 actually is on the 42d parallel.

- Sims, Hank (June 14, 2013). "Will the North Coast Marine Protected Areas Spark a War With Oregon?". Lost Coast Outpost.

- "Northern California Marine Protected Areas: Del Norte County: Pyramid Point State Marine Conservation Area". California Department of Fish and Wildlife. 1 January 2019.

- "EEUU no debe devolver Florida a España en el año 2055, el Tratado de Adams-Onís establece que la cesión es permanente". 6 February 2020.

- "No, Estados Unidos no debe devolver el estado de Florida a España en 2055". 24 February 2020.

This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "Adams–Onís Treaty", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.

Bibliography

- Marshall, Thomas Maitland (1914). A history of the western boundary of the Louisiana Purchase, 1819-1841. Berkeley, University of California Press.

- Bailey, Hugh C. (1956). "Alabama's Political Leaders and the Acquisition of Florida" (PDF). Florida Historical Quarterly. 35 (1): 17–29. ISSN 0015-4113. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-04. Retrieved 2010-02-05.

- Bemis, Samuel Flagg (1949). John Quincy Adams and the Foundations of American Foreign Policy. New York: A. A. Knopf., the standard history.

- Brooks, Philip Coolidge (1939). Diplomacy and the borderlands: the Adams–Onís Treaty of 1819.

- Warren, Harris G. "Textbook Writers and the Florida" Purchase" Myth." Florida Historical Quarterly 41.4 (1963): 325-331 online

- Weeks, William Earl (1992). John Quincy Adams and American Global Empire. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-9058-4..

- Sources

.jpg.webp)