Casta

Casta (Spanish: [ˈkasta]) is a term which means "lineage" in Spanish and Portuguese and has historically been used as a racial and social identifier. In the context of the Spanish Empire in the Americas, the term also refers to a now-discredited 20th-century theoretical framework which postulated that colonial society operated under a hierarchical race-based "caste system". From the outset, colonial Spanish America resulted in widespread intermarriage: unions of Spaniards (españoles), Amerindians (indios), and Africans (negros). Basic mixed-race categories that appeared in official colonial documentation were mestizo, generally offspring of a Spaniard and an Indigenous person; and mulatto, offspring of a Spaniard and an African. A plethora of terms were used for people with mixed Spanish, Amerindian, and African ancestry in 18th-century casta paintings, but they are not known to have been widely used officially or unofficially in the Spanish Empire.

Etymology

Casta is an Iberian word (existing in Spanish, Portuguese and other Iberian languages since the Middle Ages), meaning 'lineage'. It is documented in Spanish since 1417 and is linked to the Proto-Indo-European ger. The Portuguese casta gave rise to the English word caste during the early modern period.[1][2]

Use of casta terminology

In the historical literature, how racial distinction, hierarchy, and social status functioned over time in colonial Spanish America has been an evolving and contested discussion.[3][4] Although the term sistema de castas (system of castes) or sociedad de castas ("society of castes") are utilized in modern historical analyses to describe the social hierarchy based on race, with Spaniards at the apex, archival research shows that there is not a rigid "system" with fixed places for individuals.[5][6][7] rather, a more fluid social structure where individuals could move from one category to another, or maintain or be given different labels depending on the context. In the 18th century, "casta paintings", imply a fixed racial hierarchy, but this genre may well have been an attempt to bring order into a system that was more fluid. "For colonial elites, casta paintings might well have been an attempt to fix in place rigid divisions based on race, even as they were disappearing in social reality."[8]

Examination of registers in colonial Mexico put in question other narratives held by certain academics, such as Spanish immigrants who arrived to Mexico being almost exclusively men or that "pure Spanish" people were all part of a small powerful elite, as Spaniards were often the most numerous ethnic group in the colonial cities[9][10] and there were menial workers and people in poverty who were of complete Spanish origin.[11]

In New Spain (colonial Mexico) during the Mexican War of Independence, race and racial distinctions were an important issue and the end of imperial had a strong appeal. José María Morelos, who was registered as a Spaniard in his baptismal records, called for the abolition of the formal distinctions the imperial regime made between racial groups, advocating for "calling them one and all Americans."[12] Morelos issued regulations in 1810 to prevent ethnic-based disturbances. "He who raises his voice should be immediately punished." In 1821 race was an issue in the negotiations resulting in the Plan of Iguala.[13]

"Colonial Caste System" debate

The degree to which racial category labels had legal and social consequences has been subject to academic debate since the idea of a "caste system" was first developed by Polish-Venezuelan philologist Ángel Rosenblat and Mexican anthropologist Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán in the 1940s. Both authors popularized the notion that racial status was the key organizing principle of Spanish colonial rule, a theory which became commonplace in the anglosphere during the mid and late 20th century. However, recent academic studies in Latin America have widely challenged this notion, considering it a flawed and ideologically-based reinterpretation of the colonial period. Then, several historians have questioned the existence of this phenomenon in historical sociopolitical dynamics, considering that it could be a modern invention, which emerged during a historical revisionism in the 1940s, which would misrepresent qualifiers and lexicon of colonial culture to result in the system of castes that is narrated. Given this, this historiographical current believes that for later social scientists, the nomenclature of "castes" began to imply, arbitrarily and equivocally, that colonial society was necessarily founded on an apparent "caste system" like Caste system in India.

Pilar Gonzalbo, in her study La trampa de las castas (2013) discards the idea of the existence of a "caste system" or a "caste society" in New Spain, understood as a "social organization based on the race and supported by coercive power".[14] She also affirms in her work that certain subliminal and derogatory messages in caste paintings were not a general phenomenon, and that they only began to be carried out in particular environments of the Criollo oligarchies after the Bourbon Reformism and the influx of ideas of scientific racism from the illustration within some encyclopedic environments of the colonial bourgeoisie. A sample of the artificial construction of situations and characters in these paintings can be intuited in terms of the apparent scarce presence of Spanish women to represent the formation of miscegenation, which is very contrary to the reality of parish marriage records, which they recorded the widespread existence of Spanish women married to men of other castes. So, those who commissioned the representations of castes would be a minority of distinguished Criollo, probably functionaries of the metropolis and owners of a dubious lineage; who had a desire for social distinction, plagued with prejudice against the commoner masses (in which a large part of the indigenous peasantry was included) because of works such as that of Jean de La Bruyère (who spread the idea of a poor and miserable peasantry, almost like animals, in the encyclopedic elites of the Enlightenment). These paintings are not very reliable testimonies of racism at a mass level. [15]

Joanne Rappaport, in her book on colonial New Granada, The Disappearing Mestizo, rejects the caste system as an interpretative framework for that time, discussing both the legitimacy of a model valid for the entire colonial world and the usual association between "caste" and "race".[16]

Similarly, Berta Ares' 2015 study on the Viceroyalty of Peru, notes that the term "casta" was barely used by colonial authorities which, according to her, casts doubt on the existence of a "caste system". Even by the 18th century, its use was rare and appeared in its plural form, "castas", characterized by its ambiguous meaning. The word did not specifically refer to sectors of the population who were of mixed race, but also included both Spaniards and Indians of lower socio-economic extraction, often used together with other terms such as plebe, vulgo, naciones, clases, calidades, otras gentes, etc.[17]

Ben Vinson, in a study of the historical archives of Mexico carried out in 2018, addressing the issue of racial diversity in Mexico and its relationship with imperial Spain, ratified these conclusions.[18]

Often called the sistema de castas or the sociedad de castas, there was, in fact, no fixed system of classification for individuals, as careful archival research has shown. There was considerable fluidity in society, with the same individuals being identified by different categories simultaneously or over time. Individuals self-identified by particular terms, often to shift their status from one category to another to their advantage. For example, both mestizos and Spaniards were exempt from tribute obligations, but were both equally subject to the Inquisition. Indios, on the other hand, paid tribute yet were exempt from the Inquisition. In certain cases, a mestizo might try to "pass" as an indio to escape the Inquisition. An indio might try to pass as a Mestizo to escape tribute obligations.[19]

Casta paintings produced largely in 18th-century Mexico have influenced modern understandings of race in Spanish America, a concept which began infiltrating Bourbon Spain from France and Northern Europe during this time. They purport to show a fixed "system" of racial hierarchy which has been disputed by modern academia. These paintings should be evaluated as the production by elites in New Spain for an elite viewership in both Spanish territories and abroad portrayals of mixtures of Spaniards with other ethnicities, some of which have been interpreted as being pejorative in nature or seeking social outrage. They are thus useful for understanding elites and their attitudes toward non-elites, and quite valuable as illustrations of aspects of material culture in the late colonial era.[20]

The process of mixing ancestries by the union of people of different races is known in the modern era as mestizaje (Portuguese: mestiçagem [mestʃiˈsaʒẽj], [mɨʃtiˈsaʒɐ̃j]). In Spanish colonial law, mixed-race castas were classified as part of the república de españoles and not the república de indios, which set Amerindians outside the Hispanic sphere with different duties and rights to those of Spaniards and Mestizos.

The caste system for these revisionists would have been misconstrued as being analogous to the castes of India. Given that in viceregal Spanish America there was never a closed system based on birth rights, where the birth rate and, therefore, wealth, created a "caste system" difficult to penetrate; but, rather, the statute of Limpieza de sangre (a concept of religious root and not biological or racial) was given, in which the Indian and the mestizo, as a new Christian, had limitations on access to certain trades until assimilation full of his conversion to Catholicism; but that did not prevent his social ascent, and he would even receive protections that would benefit his social mobilization, protections that the old Christian of the Republica de españoles would not enjoy (such as being free from all the taxes of the whites, with the exception of the indigenous tribute, or be exempt from the Holy Inquisition). Then, those conceptions of a "caste society" or a "caste system" as characteristic of colonial society would be completely anachronistic formulations and could be part of the Spanish Black Legend. Given this, in works prior to those of Rosenblat and Beltrán, one would not find references to the notion that the Spanish empire was a society founded on racial segregation. Neither in Nicolás León, Gregorio Torres Quintero, Blanchard, nor in the Catalog of Herrera and Cicero (1895), nor in the article "Castas" of the Dictionary of History and Geography (1855), nor in Alexander von Humboldt's Political Essay on the Spanish-American territories that he visited on his scientific expeditions. Among other works that refer to the existence of castes and caste paintings, without implying connotations with modern racism, which would come to America after the French Enlightenment.[21]

This would make these critics conclude that those colonial societies were rather of the class type, that although there was a relationship between class and race through castes, that was not in a cause relationship, but in a consequence relationship ( not being an end in itself the race, which was understood in the Hispanic tradition as something purely spiritual, not so much biological). The purpose of the castas was to register the identity of lineages to register them in the republic of Spaniards, the republic of Indians, with the services and privileges acquired, which would not disturb the economic potential of the individual of the caste, nor would they have the purpose of to formally segregate them from positions of power, but to hierarchize them in feudal society (not equivalent to the same thing, as long as they were not prevented from ascending to the nobility or being part of the commercial petty bourgeoisie). Then, the viceroyalty society would be a society of "quality", estate, corporate, patronage and trade union, where each social group was not conditioned by their race, and neither did this establish the labor relations of its inhabitants. In the parish registers there would never have been the tendency to classify in so many innumerable mixtures as seen in the caste charts, which would be an artistic phenomenon typical of the Age of Enlightenment.[22][23]

Some examples of blacks, mulattoes and mestizos who climbed socially would be used as evidence against these misrepresentations, such as: Juan Latino, Juan Valiente, Juan Garrido, Juan García, Juan Bardales, Sebastián Toral, Antonio Pérez, Miguel Ruíz, Gómez de León,[24][25] Fran Dearobe, José Manuel Valdés, Teresa Juliana de Santo Domingo. Names of indigenous chiefs and noble mestizos are also mentioned: Carlos Inca, Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, Manuela Taurichumbi Saba Cápac Inca, Alonso de Castilla Titu Atauchi Inga, Alonso de Areanas Florencia Inca, Gonzalo Tlaxhuexolotzin, Vicente Xicohténcatl, Bartolomé Zitlalpopoca, Lorenzo Nahxixcalzin , Doña Luisa Xicotencatl, Nicolás de San Luis Montañez, Fernando de Tapia, Isabel Moctezuma Tecuichpo Ixcaxochitzin, Pedro de Moctezuma. The Royal Decree of Philip II on 1559 is also often mentioned, in which it is prescribed that "the mestizos who come to these kingdoms to study, or for other things of their use (...) do not need another license to return." The document is important, because laws are not made for particular cases and it shows that the existence of multiple castes did not impede social mobilization within the Hispanic monarchy, the same mobilization that must have been significant to require the attention of a royal edict of the person of the Spanish king.[26]

"Purity of blood" and the evolution of racial classification

Certain authors have sought to link the castas in Latin America to the older Spanish concept of "purity of blood", limpieza de sangre, originating under Moorish rule, developed in Christian Spain to denote those without recent Jewish or Muslim heritage or, more widely, heritage from individuals convicted by the Spanish inquisition for heresy.

It was directly linked to religion and notions of legitimacy, lineage and honor following Spain's reconquest of Moorish territory and the degree to which it can be considered a precursor to the modern concept of race has been the subject of academic debate.[27] The Inquisition only allowed those Spaniards who could demonstrate not to have Jewish and Moorish blood to emigrate to Latin America, although this prohibition was frequently ignored and a number of Spanish Conquistadors were Jewish Conversos. Others, such as Juan Valiente, were Black Africans or had recent Moorish ancestry.

Both in Spain and in the New World Conversos who continued to practice Judaism in secret were aggressively prosecuted. Of the roughly 40 people executed by the Spanish Inquisition in Mexico, a significant number were convicted of being "Judaizers" (judaizantes) .[28] Spanish Conquistador Luis de Carvajal y de la Cueva was prosecuted by the Inquisition for secretly practising Judaism and eventually died in prison.

In Spanish America, the idea of purity of blood also applied to Black Africans and indigenous peoples since, as Spaniards of Moorish and Jewish descent, they had not been Christian for various generations and were inherently suspect of engaging in religious heresy. In all Spanish territories, including Spain itself, evidence of lack of purity of blood had consequences for eligibility for office, entrance into the priesthood, and emigration to Spain's overseas territories. Having to produce genealogical records to prove one's pure ancestry gave rise to a trade in the creation of false genealogies, a practice which was already widespread in Spain itself.[29]

This was no impediment for intermarriage between Spaniards and indigenous people, just as it had not been between Old and New Christians or different racial groups coexisting in late medieval and early modern Spain. The result was generations of mixed-race children who were typically considered Spaniards, and many of whom returned to Spain to join the ranks of the nobility, a notable example being Juan Cano Moctezuma.

However, starting in the late 16th century, some investigations of ancestry classified as "stains" any connection with Black Africans ("negros", which resulted in "mulatos") and sometimes mixtures with indigenous that produced Mestizos.[30] While some illustrations from the period show men of African descent dressed in fashionable clothing and as aristocrats in upper-class surroundings, the idea that any hint of black ancestry was a stain developed by the end of the colonial period, a time in which biological racism began to emerge throughout the western world. This trend was illustrated in 18th-century paintings of racial hierarchy, known as casta paintings which led to 20th-century emergence of theories on a "Caste System" existing in Colonial Spanish America.

The idea in New Spain that native or "Indian" (indio) blood in a lineage was an impurity may well have come about as the optimism of the early Franciscans faded about creating Indian priests trained at the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlatelolco, which ceased that function in the mid-16th century. In addition, the Indian nobility, which was recognized by the Spanish colonists, had declined in importance, and there were fewer formal marriages between Spaniards and indigenous women than during the early decades of the colonial era.[30] In the 17th century in New Spain, the ideas of purity of blood became associated with "Spanishness and whiteness, but it came to work together with socio-economic categories", such that a lineage with someone engaged in work with their hands was tainted by that connection.[31]

Indians in Central Mexico were affected by ideas of purity of blood from the other side. Crown decrees on purity of blood were affirmed by indigenous communities, which barred Indians from holding office who had any non-Indians (Spaniards and/or Black peoples) in their lineage. In indigenous communities "local caciques [rulers] and principales were granted a set of privileges and rights on the basis of their pre-Hispanic noble bloodlines and acceptance of the Catholic faith."[32] Indigenous nobles submitted proofs (probanzas) of their purity of blood to affirm their rights and privileges that were extended to themselves and their communities. This supported the república de indios, a legal division of society that separated indigenous from non-Indians (república de españoles).[33]

Casta classifications and legal consequences

In Spanish America racial categories were registered at local parishes upon baptism as required by the Spanish Crown. Initially in Spanish America there were three ethnic categories. They generally referred to the multiplicity of indigenous American peoples as "Indians" (indios). Those from Spain called themselves españoles. The third group were black Africans, called negros (lit. "blacks"), brought as slaves from the earliest days of Spanish Empire. Although intermarriage was widespread from the beginning of the colonial period, mestizos only slowly began to be recognized as a distinct ethnicity 150 years after the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, prior to which they had simply been identified as Spaniards.

Although the number of Spanish women emigrating to New Spain was far higher than is often portrayed, they were fewer in number than men, as well as fewer black women than men, so the mixed-race offspring of Spaniards and of Black people were often the product of liaisons with indigenous women. The process of race mixture is now termed mestizaje, a term coined in the modern era.

In the 16th century, the term casta, a collective category for mixed-race individuals, came into existence as the numbers grew, particularly in urban areas. Nevertheless, during the first century and a half of the colonial era, the offspring of mixed marriages were registered as Spaniards and only Africans were registered as "Castas". The registry of "Mestizos" as "Castas" rather than "Spaniards" only become widespread in the last century of colonial rule.

The crown had divided the population of its overseas empire into two categories, separating Indians from non-Indians. Indigenous were the República de Indios, the other the República de Españoles, essentially the Hispanic sphere, so that Spaniards, Black people, and mixed-race castas were lumped into this category. Official censuses and ecclesiastical records noted an individual's racial category, so that these sources can be used to chart socio-economic standard, residence patterns, and other important data.

General racial groupings had their own set of privileges and restrictions, both legal and customary. So, for example, only Spaniards and indigenous, who were deemed to be the original societies of the Spanish dominions, had recognized aristocracies.[34][35] In the population at large, access to social privileges and even at times a person's perceived and accepted racial classification, were predominantly determined by that person's socioeconomic standing in society.[36][37][38]

Official censuses and ecclesiastical records noted an individual's racial category, so that these sources can be used to chart socio-economic standards, residence patterns, and other important data. Parish registers, where baptism, marriage, and burial were recorded, had three basic categories: español (Spaniards), indio, and color quebrado ("broken color", indicating a mixed-race person). In some parishes in colonial Mexico, indios were recorded with other non-Spaniards in the color quebrado register.[39] Españoles and mestizos could be ordained as priests and were exempt from payment of tribute to the crown. Free black people, Amerindians, and mixed-race castas were required to pay tribute and barred from the priesthood. Being designated as an español or mestizo conferred social and financial advantages. Men of color began to apply to the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico, but in 1688 Bishop Juan de Palafox y Mendoza attempted to prevent their entrance by drafting new regulations barring black peoples and mulattoes.[40] In 1776, the crown issued the Royal Pragmatic on Marriage, taking approval of marriages away from the couple and placing it in their parents' hands. The marriage between Luisa de Abrego, a free black domestic servant from Seville and Miguel Rodríguez, a white Segovian conquistador in 1565 in St. Augustine (Spanish Florida), is the first known and recorded Christian marriage anywhere in the continental United States.[41]

Long lists of different terms found in casta paintings do not appear in official documentation or anywhere outside these paintings. Only counts of Spaniards, mestizos, black peoples and mulattoes, and indigenes (indios), were recorded in censuses.[42]

Casta paintings of the 18th century

_LACMA_M.2011.20.3_(1_of_6).jpg.webp)

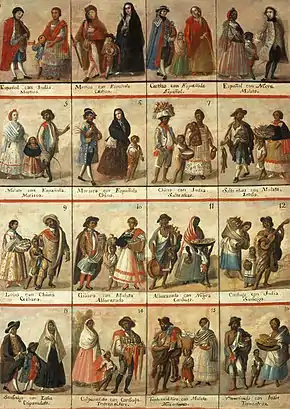

Artwork created mainly in 18th-century Mexico purports to show race mixture as a hierarchy. These paintings have had tremendous influence in how scholars have approached difference in the colonial era, but should not be taken as definitive description of racial difference. For approximately a century, casta paintings were by elite artists for an elite viewership. They ceased to be produced following Mexico's independence in 1821 when casta designations were abolished. The vast majority of casta paintings were produced in Mexico, by a variety of artists, with a single group of canvases clearly identified for 18th-century Peru. In the colonial era, artists primarily created religious art and portraits, but in the 18th century, casta paintings emerged as a completely secular genre of art. An exception to that is the painting by Luis de Mena, a single canvas that has the central figure of the Virgin of Guadalupe and a set of casta groupings.[43] Most sets of casta paintings have 16 separate canvases, but a few, such as Mena's, Ignacio María Barreda, and the anonymous painting in the Museo de Virreinato in Tepozotlan, Mexico, are frequently reproduced as examples of the genre, likely because their composition gives a single, tidy image of the racial classification (from the elite viewpoint).

It is unclear why casta paintings emerged as a genre, why they became such a popular genre of artwork, who commissioned them, and who collected them. One scholar suggests they can be seen as "proud renditions of the local,"[44] at a point when American-born Spaniards began forming a clearer identification with their place of birth rather than metropolitan Spain.[45] The single-canvas casta artwork could well have been as a curiosity or souvenir for Spaniards to take home to Spain; two frequently reproduced casta paintings are Mena's and Barreda's, both of which are in Madrid museums.[46] There is only one set of casta paintings definitively done in Peru, commissioned by Viceroy Manuel Amat y Junyent (1770), and sent to Spain for the Cabinet of Natural History of the Prince of Asturias.[47]

The influence of the European Enlightenment on the Spanish empire led to an interest in organizing knowledge and scientific description might have resulted in the commission of many series of pictures that document the racial combinations that existed in Spanish territories in the Americas. Many sets of these paintings still exist (around one hundred complete sets in museums and private collections and many more individual paintings), of varying artistic quality, usually consisting of sixteen paintings representing as many racial combinations. It must be emphasized that these paintings reflected the views of the economically established Criollo society and officialdom, but not all Criollos were pleased with casta paintings. One remarked that they show "what harms us, not what benefits us, what dishonors us, not what ennobles us."[48] Many paintings are in Spain in major museums, but many remain in private collections in Mexico, perhaps commissioned and kept because they show the character of late colonial Mexico and a source of pride.[49]

Some of the finer sets were done by prominent Mexican artists, such as José de Alcíbar, Miguel Cabrera, José de Ibarra, José Joaquín Magón, (who painted two sets); Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz, José de Páez, and Juan Rodríguez Juárez. One of Magón's sets includes descriptions of the "character and moral standing" of his subjects. These artists worked together in the painting guilds of New Spain. They were important transitional artists in 18th-century casta painting. At least one Spaniard, Francisco Clapera, also contributed to the casta genre. In general, little is known of most artists who did sign their work; most casta paintings are unsigned.

Certain authors have interpreted the overall theme of these paintings as representing the "supremacy of the Spaniards", the possibility that mixtures of Spaniards and Spanish-Indian offspring could return to the status of Spaniards through marriage to Spaniards over generations, what can be considered "restoration of racial purity,"[50] or "racial mending"[51] was seen visually in many sets of casta paintings. It was also articulated by a visitor to Mexico, Don Pedro Alonso O'Crouley, in 1774. "If the mixed-blood is the offspring of a Spaniard and an Indian, the stigma [of race mixture] disappears at the third step in descent because it is held as systematic that a Spaniard and an Indian produce a mestizo; a mestizo and a Spaniard, a castizo; and a castizo and a Spaniard, a Spaniard. The admixture of Indian blood should not indeed be regarded as a blemish, since the provisions of law give the Indian all that he could wish for, and Philip II granted to mestizos the privilege of becoming priests. On this consideration is based the common estimation of descent from a union of Indian and European or creole Spaniard."[52]

O'Crouley says that the same process of restoration of racial purity does not occur over generations for European-African offspring marrying whites. “From the union of a Spaniard and a Negro the mixed-blood retains the stigma for generations without losing the original quality of a mulato."[53] Casta paintings show increasing whitening over generations with the mixes of Spaniards and Africans. The sequence is the offspring of a Spaniard + Negra, Mulatto; Spaniard with a Mulatta, Morisco; Spaniard with a Morisca, Albino (a racial category, derived from Alba, "white"); Spaniard with an Albina, Torna atrás, or "throw back" black. Negro, Mulatto, and Morisco were labels found in colonial-era documentation, but Albino and Torna atrás exist only as fairly standard categories in casta paintings.

In contrast, mixtures with Black people, both by Indians and Spaniards, led to a bewildering number of combinations, with "fanciful terms" to describe them. Instead of leading to a new racial type or equilibrium, they led to apparent disorder. Terms such as the above-mentioned tente en el aire ("floating in mid air") and no te entiendo ("I don't understand you")—and others based on terms used for animals: coyote and lobo (wolf).[54][55]

Castas defined themselves in different ways, and how they were recorded in official records was a process of negotiation between the casta and the person creating the document, whether it was a birth certificate, a marriage certificate or a court deposition. In real life, many casta individuals were assigned different racial categories in different documents, revealing the malleable nature of racial identity in colonial, Spanish American society.[56]

Some paintings depicted the supposed "innate" character and quality of people because of their birth and ethnic origin. For example, according to one painting by José Joaquín Magón, a mestizo (mixed Indian + Spanish) was considered generally humble, tranquil, and straightforward; while another painting claims "from Lobo and Indian woman is born the Cambujo, one usually slow, lazy, and cumbersome." Ultimately, the casta paintings are reminders of the colonial biases in modern human history that linked a caste/ethnic society based on descent, skin color, social status, and one's birth.[57][58]

Often, casta paintings depicted commodity items from Latin America like pulque, the fermented alcohol drink of the lower classes. Painters depicted interpretations of pulque that were attributed to specific castas.

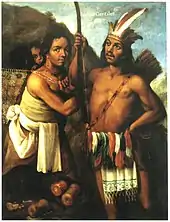

The Indias in casta paintings depict them as partners to Spaniards, Black people, and castas, and thus part of Hispanic society. But in a number of casta paintings, they are also shown apart from "civilized society," such as Miguel Cabrera's Indios Gentiles, or indios bárbaros or Chichimecas barely clothed indigenous in a wild, setting.[59] In the single-canvas casta painting by José María Barreda, there are a canonical 16 casta groupings and then in a separate cell below are "Mecos". Although the so-called "barbarian Indians" (indios bárbaros) were fierce warriors on horseback, indios in casta paintings are not shown as bellicose, but as weak, a trope that developed in the colonial era.[60] A casta painting by Luis de Mena that is often reproduced as an example of the genre shows an unusual couple with a pale, well-dressed Spanish woman paired with a nearly naked indio, producing a Mestizo offspring. "The aberrant combination not only mocks social protocol but also seems to underscore the very artificiality of a casta system that pretends to circumscribe social fluidity and economic mobility."[61] The image "would have seemed frankly bizarre and offensive by eighteenth-century Creole elites, if taken literally", but if the pair were considered allegorical figures, the Spanish woman represents "Europe" and the indio "America."[62] The image "functions as an allegory for the 'civilizing' and Christianizing process."[63]

Sample sets of casta paintings

Presented here are casta lists from three sets of paintings. Note that they only agree on the first five combinations, which are essentially the Indian-White ones. There is no agreement on the Black mixtures, however. Also, no one list should be taken as "authoritative". These terms would have varied from region to region and across time periods. The lists here probably reflect the names that the artist knew or preferred, the ones the patron requested to be painted, or a combination of both.

| Miguel Cabrera, 1763[64] | Andrés de Islas, 1774[65] | Anonymous (Museo del Virreinato)[66] | |

|

|

|

Casta paintings

_LACMA_M.2011.20.2_(5_of_5).jpg.webp) De español, Alvina, Torna atrás. Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz (1701-1770)

De español, Alvina, Torna atrás. Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz (1701-1770).jpg.webp) De Albina y Español, Torna atrás. Attributed to Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz.

De Albina y Español, Torna atrás. Attributed to Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz. De español e india, produce mestizo (From a Spanish man and an Amerindian woman, a Mestizo is produced).

De español e india, produce mestizo (From a Spanish man and an Amerindian woman, a Mestizo is produced). Spaniard and Torna atrás, Tente en el aire. Miguel Cabrera.

Spaniard and Torna atrás, Tente en el aire. Miguel Cabrera. De mestizo e india, sale coiote (From a Mestizo man and an Amerindian woman, a Coyote is begotten).

De mestizo e india, sale coiote (From a Mestizo man and an Amerindian woman, a Coyote is begotten). Spaniard + Negra, Mulatto. Miguel Cabrera.

Spaniard + Negra, Mulatto. Miguel Cabrera. De español y mulata, morisca. Miguel Cabrera, 1763, oil on canvas, 136x105 cm, private collection.

De español y mulata, morisca. Miguel Cabrera, 1763, oil on canvas, 136x105 cm, private collection. José Joaquín Magón, IV. Spaniard + Negra = Mulata. "The pride and sharp wits of the Mulata are instilled in her white father and black mother"

José Joaquín Magón, IV. Spaniard + Negra = Mulata. "The pride and sharp wits of the Mulata are instilled in her white father and black mother" Canbujo con Yndia sale Albaracado / Notentiendo con Yndia sale China, óleo sobre lienzo, 222 x 109 cm, Madrid, Museo de América

Canbujo con Yndia sale Albaracado / Notentiendo con Yndia sale China, óleo sobre lienzo, 222 x 109 cm, Madrid, Museo de América De Mestizo y Albarazada, Barsina. Anon. 18th c.

De Mestizo y Albarazada, Barsina. Anon. 18th c. De Chino y Mulata, Alvarazada. Anon. 18th c.

De Chino y Mulata, Alvarazada. Anon. 18th c. De Chino, e India. Genizara. "From Indian and African Mixed father, and Indian mother. Genizara." by Francisco Clapera

De Chino, e India. Genizara. "From Indian and African Mixed father, and Indian mother. Genizara." by Francisco Clapera

See also

References

- "Caste", Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 10th edition. (Springfield, 1999.)

- "Caste", New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd edition. (Oxford, 2005).

- Giraudo, Laura (14 June 2018). "Casta(s), 'sociedad de castas' e indigenismo: la interpretación del pasado colonial en el siglo XX". Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos. doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.72080.

- Vinson, Ben III. Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico. New York: Cambridge University Press 2018.

- Cope, R. Douglas. The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico City, 1660–1720. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994.

- Valdés, Dennis N., "Decline of the Sociedad de Castas in Eighteenth-Century Mexico." PhD diss. University of Michigan, 1978

- Rappaport, Joanne. The Disappearning Mestizo: Configuring Difference in the Colonial New Kingdom of Granada. Durham: Duke University Press 2014.

- Cline, Sarah (1 August 2015). "Guadalupe and the Castas". Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos. 31 (2): 218–247. doi:10.1525/mex.2015.31.2.218.

- Sherburne Friend Cook; Woodrow Borah (1998). Ensayos sobre historia de la población. México y el Caribe 2. Siglo XXI. p. 223. ISBN 9789682301063. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- Hardin, Monica L. (2016). Household Mobility and Persistence in Guadalajara, Mexico: 1811–1842. Lexington Books. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4985-4072-8.

- San Miguel, G. (November 2000). "Ser mestizo en la nueva España a fines del siglo XVIII: Acatzingo, 1792" [To be 'mestizo' in New Spain at the end of the XVIIIth century. Acatzingo, 1792]. Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales. Universidad Nacional de Jujuy (in Spanish) (13): 325–342.

- quoted in Enrique Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997, p. 112

- quoted in Krauze, Mexico, p. 111.

- Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Pilar, "La trampa de las castas" in Alberro, Solange and Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Pilar, La sociedad novohispana. Estereotipos y realidades, México, El Colegio de México, 2013, p. 15–193.

- Educación, familia y vida cotidiana en México virreinal, de Pilar Gonzalbo Aizpuru, El Colegio de México.

- Rappaport, Joanne (4 April 2014). The Disappearing Mestizo: Configuring Difference in the Colonial Kingdom of New Granada. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822356363.

- Ares, Berta, “Usos y abusos del concepto de casta en el Perú colonial”, ponencia presentada en el Congreso Internacional INTERINDI 2015. Categorías e indigenismo en América Latina, EEHA-CSIC, Sevilla, 10 de noviembre de 2015. Citado con la autorización de la autora.

- Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico. Cambridge University Press. 2018. ISBN 9781107026438.

- Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Pilar, "La trampa de las castas" in Alberro, Solange and Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Pilar, La sociedad novohispana. Estereotipos y realidades, México, El Colegio de México, 2013, p. 15–193.

- Katzew, Ilona. Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven: Yale University Press 2004.

- Giraudo, Laura (2018-06-14). "Casta(s), "sociedad de castas" e indigenismo: la interpretación del pasado colonial en el siglo XX". Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos. Nouveaux Mondes Mondes Nouveaux - Novo Mundo Mundos Novos - New World New Worlds (in Spanish). doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.72080. hdl:10261/167130. ISSN 1626-0252. S2CID 165569000.

- "Castas y corporaciones | Víctor R. Nomberto, Doctor en Ciencias Sociales" (in European Spanish). 2014-10-18. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- Santiago Paúl Yépez

- Ferro, Redes Desperta (2019-05-22). "Los conquistadores negros. El papel africano en la conquista de América". Desperta Ferro Ediciones (in Spanish). Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- Álvarez, Jorge (2016-04-23). "Los conquistadores españoles de 'raza' negra". La Brújula Verde (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- García, Juan Andreo (1994). Familia, tradición y grupos sociales en América Latina (in Spanish). EDITUM. ISBN 978-84-7564-151-5.

- Maria Elena Martinez, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico, Stanford: Stanford University Press 2008, p. 265.

- Jonathan I. Israel, Race, Class, and Politics in Colonial Mexico, 1610-1670. Oxford: Oxford University Press 1975, pp. 245-46.

- Martinez, Genealogical Fictions, p. 266-67.

- Martinez, Genealogical Fictions, p. 267.

- Martinez, Genealogical Fictions, p. 269.

- Martinez, Genealogical Fictions, p. 270.

- Martinez, Genealogical Fictions, p. 273.

- MacLachlan, Colin; Jaime E. Rodríguez O. (1990). The Forging of the Cosmic Race: A Reinterprretation of Colonial Mexico (Expanded ed.). Berkeley: University of California. pp. 199, 208. ISBN 978-0-520-04280-3.

[I]n the New World all Spaniards, no matter how poor, claimed hidalgo status. This unprecedented expansion of the privileged segment of society could be tolerated by the Crown because in Mexico the indigenous population assumed the burden of personal tribute.

- Gibson, Charles (1964). The Aztecs Under Spanish Rule. Stanford: Stanford University. pp. 154–165. ISBN 978-0-8047-0912-5.

- See Passing (racial identity) for a discussion of a related phenomenon, although in a later and very different cultural and legal context.

- Seed, Patricia (1988). To Love, Honor, and Obey in Colonial Mexico: Conflicts over Marriage Choice, 1574-1821. Stanford: Stanford University. pp. 21–23. ISBN 978-0-8047-2159-2.

- Bakewell, Peter (1997). A History of Latin America. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. pp. 160–163. ISBN 978-0-631-16791-4.

The Spaniards generally regarded [local Indian lords/caciques] as hidalgos, and used the honorific 'don' with the more eminent of them. […] Broadly speaking, Spaniards in the Indies in the 16th century arranged themselves socially less and less by Iberian criteria or frank, and increasingly by new American standards. […] simple wealth gained from using America's human and natural resources soon became a strong influence on social standing.

- Vinson, Before Mestizaje, p. 49.

- Ramos-Kittrell, Jesús (2016). Playing in the Cathedral: Music, Race, and Status in New Spain. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 39–40.

- J. Michael Francis, PhD, Luisa de Abrego: Marriage, Bigamy, and the Spanish Inquisition, University of South Florida, archived from the original on 2021-02-04, retrieved 2019-08-31

- Sonia G. Benson, ed. (2003), The Hispanic American Almanac: A Reference Work on Hispanics in the United States. (Third ed.), Thomson Gale, p. 14, ISBN 978-0-7876-2518-4

- Cline, "Guadalupe and the Castas" pp. 222-23

- Katzew, Ilona, "Casta Painting: Identity and Social Stratification in Colonial Mexico," in New World Orders: Casta Painting and Colonial Latin America,ed. Ilona Katzew. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery 1996, 22

- Brading, D.A. The First America: The Spanish Monarchy, Creole Patriots, and the Liberal State, 1492-1867. New York: Cambridge University Press 1991.

- García Sáiz, María Concepción. Las castas mexicanas. Milan: Olivetti 1989, 20.

- Donahue-Wallace, Kelly. Art and Architecture of Viceregal Latin America, 1521-1821. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2008, p. 221. She reproduces a letter from Amat concerning the paintings.

- quoted in Katzew, Ilona, "Casta Painting: Identity and Social Stratification in Colonial Mexico, in New World Orders: Casta Painting and Colonial Latin America. exhib. cat. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery 1996, 14.

- Donahue-Wallace, p. 220.

- Cline, "Guadalupe and the Castas", p. 229

- Katzew, Casta Painting, pp. 48-51

- Sr. Don Pedro Alonso O’Crouley, A Description of the Kingdom of New Spain (1774),trans. and ed. Sean Galvin. San Francisco: John Howell Books, 1972, 20

- O’Crouley, “A Description of the Kingdom of New Spain’’, p. 20

- Cuevas, Marco Polo Hernández (June 2012). "The Mexican Colonial Term 'Chino' Is a Referent of Afrodescendant". The Journal of Pan African Studies. 5 (5): 124–143. S2CID 142322782.

- Katzew, "Casta Painting."

- Cope, The Limits of Racial Domination and Seed, To Love, Honor, and Obey, in passim.

- Martínez López, María Elena (2002). The Spanish concept of limpieza de sangre and the emergence of the 'race/caste' system in the Viceroyalty of New Spain (Thesis). OCLC 62284377. ProQuest 305466668.

- Martínez, María Elena (2010). "Social Order in the Spanish New World" (PDF).

- Estrada de Gerlero, Elena Isabel. "The Representation of 'Heathen Indians' in Mexican Casta Painting," in New World Orders: Casta Painting and Colonial Latin America, ed. Ilona Katzew. Exh.cat. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery 1996.

- Lewis, Laura A. (June 1996). "The 'Weakness' of Women and the feminization of the Indian in colonial Mexico". Colonial Latin American Review. 5 (1): 73–94. doi:10.1080/10609169608569878.

- Peterson, Jeanette Favrot, Visualizing Guadalulpe. p. 258

- Cline, "Guadalupe and the Castas", p. 225

- Martinez, Maria Elena. Genealogical Fictions, p. 256

- Katzew (2004), Casta Painting, 101-106. Paintings 1 and 3-8 private collections; 2 and 9-16 Museo de América, Madrid; 15 Elisabeth Waldo-Dentzel, Multicultural Music and Art Center (Northridge California).

- Katzew, Ilona. Program for Inventing Race: Casta Painting and Eighteenth-Century Mexico, April 4-August 8, 2004. LACMA

- Gracia, J. E. and Pablo De Greiff, eds. Hispanics/Latinos in the United States: Ethnicity, Race and Rights. New York, Routledge, 2000, 53. ISBN 978-0-415-92620-1

- Christopher Knight, "A Most Rare Couch Find: LACMA acquires a recently unrolled masterpiece." Los Angeles Times, April 1, 2015, A1.

Further reading

Race and race mixture

- Althouse, Aaron P. (October 2005). "Contested Mestizos, Alleged Mulattos: Racial Identity and Caste Hierarchy in Eighteenth Century Pátzcuaro, Mexico". The Americas. 62 (2): 151–175. doi:10.1353/tam.2005.0155. S2CID 143688536.

- Anderson, Rodney D. (1 May 1988). "Race and Social Stratification: A Comparison of Working-Class Spaniards, Indians, and Castas in Guadalajara, Mexico in 1821". Hispanic American Historical Review. 68 (2): 209–243. doi:10.1215/00182168-68.2.209.

- Andrews, Norah (April 2016). "Calidad , Genealogy, and Disputed Free-colored Tributary Status in New Spain". The Americas. 73 (2): 139–170. doi:10.1017/tam.2016.35. S2CID 147913805.

- Burns, Kathryn. "Unfixing Race," in Rereading the Black Legend: The Discourses of Religious and Racial Difference in the Renaissance Empires, ed. Margaret Greer et al. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2007.

- Castleman, Bruce A (December 2001). "Social Climbers in a Colonial Mexican City: Individual Mobility within the Sistema de Castas in Orizaba, 1777-1791". Colonial Latin American Review. 10 (2): 229–249. doi:10.1080/10609160120093796. S2CID 161154873.

- Chance, John K. Race and class in Colonial Oaxaca, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1978.

- Cope, R. Douglas. The Limits of Racial Domination: Plebeian Society in Colonial Mexico City, 1660-1720. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-299-14044-1

- Fisher, Andrew B. and Matthew D. O'Hara, eds. Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America. Durham: Duke University Press 2009.

- Garofalo, Leo J.; O'Toole, Rachel Sarah (2006). "Introduction: Constructing Difference in Colonial Latin America". Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History. 7 (1). doi:10.1353/cch.2006.0027. S2CID 161860137.

- Giraudo, Laura (14 June 2018). "Casta(s), 'sociedad de castas' e indigenismo: la interpretación del pasado colonial en el siglo XX". Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos. doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.72080.

- Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Pilar, "La trampa de las castas," in Alberro, Solange y Gonzalbo Aizpuru, Pilar, La sociedad novohispana. Estereotipos y realidades, México, El Colegio de México, 2013, p. 15-193.

- Hill, Ruth. "Casta as Culture and the Sociedad de Castas a Literature," in Interpreting Colonialism. ed. Byron Wells and Philip Stewart. New York: Oxford University Press 2004.

- Jackson, Robert H. Race, Caste, and Status: Indians in Colonial Spanish America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1999.

- Leibsohn, Dana, and Barbara E. Mundy, "Reckoning with Mestizaje," Vistas: Visual Culture in Spanish America, 1520-1820 (2015). http://www.fordham.edu/vistas.

- MacLachlan, Colin M. and Jaime E. Rodríguez O. The Forging of the Cosmic Race: A Reinterpretation of Colonial Mexico, expanded edition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990. ISBN 0-520-04280-8

- Martínez, María Elena, Genealogical Fictions: Limpieza de Sangre, Religion, and Gender in Colonial Mexico, Stanford: Stanford University Press 2008,

- McCaa, Robert (1 August 1984). "Calidad, Clase, and Marriage in Colonial Mexico: The Case of Parral, 1788-90". Hispanic American Historical Review. 64 (3): 477–501. doi:10.1215/00182168-64.3.477.

- Mörner, Magnus. Race Mixture in the History of Latin America. Boston: Little Brown, 1967.

- O'Crouley, Pedro Alonso. A Description of the Kingdom of New Spain. Translated and edited by Sean Galvin. John Howell Books 1972.

- O'Toole, Rachel Sarah. Bound Lives: Africans, Indians, and the Making of Race in Colonial Peru. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press 2012. ISBN 978-0-8229-6193-2

- Pitt-Rivers, Julian, "Sobre la palabra casta", América Indígena, 36-3, 1976, pp. 559-586.

- Ramos-Kittrell, Jesús. Playing in the Cathedral: Music, Race, and Status in New Spain. New York: Oxford University Press 2016.

- Rappaport, Joanne. The Disappearing Mestizo: Configuring Difference in the Colonial Kingdom of New Granada. Durham: Duke University Press 2014.

- Rosenblat, Angel. El mestizaje y las castas coloniales: La población indígena y el mestizaje en América. buenos Aires, Editorial Nova 1954.

- Seed, Patricia. To Love, Honor, and Obey in Colonial Mexico: Conflicts Over Marriage Choice, 1574-1821. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988. ISBN 978-0-8047-1457-0

- Seed, Patricia (1 November 1982). "Social Dimensions of Race: Mexico City, 1753". Hispanic American Historical Review. 62 (4): 569–606. doi:10.1215/00182168-62.4.569.

- Twinam, Ann. Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulatos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2015.

- Valdés, Dennis Nodín (1978). The decline of the sociedad de castas in Mexico City (Thesis). University of Michigan. OCLC 760496135.

- Vinson, Ben III. Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico. New York: Cambridge University Press 2018 ISBN 978-1-107-67081-5

- Wade, Peter (May 2005). "Rethinking Mestizaje : Ideology and Lived Experience". Journal of Latin American Studies. 37 (2): 239–257. doi:10.1017/S0022216X05008990. S2CID 96437271.

Casta painting

- Carrera, Magali M. Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings. Austin, University of Texas Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-292-71245-4

- Cline, Sarah (1 August 2015). "Guadalupe and the Castas". Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos. 31 (2): 218–247. doi:10.1525/mex.2015.31.2.218. S2CID 7995543.

- Cummins, Thomas B. F. (2006). "Review of Casta Paintings: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico, ; Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings". The Art Bulletin. 88 (1): 185–189. JSTOR 25067234.

- Dean, Carolyn; Leibsohn, Dana (June 2003). "Hybridity and Its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish America". Colonial Latin American Review. 12 (1): 5–35. doi:10.1080/10609160302341. S2CID 162937582.

- Earle, Rebecca (2016). "The Pleasures of Taxonomy: Casta Paintings, Classification, and Colonialism" (PDF). The William and Mary Quarterly. 73 (3): 427–466. doi:10.5309/willmaryquar.73.3.0427. S2CID 147847406.

- Estrada de Gerlero, Elena Isabel. "Representations of 'Heathen Indians' in Mexican Casta Painting," in New World Orders, Ilona Katzew, ed. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery 1996.

- García Sáiz, María Concepción. Las castas mexicanas: Un género pictórico americano. Milan: Olivetti 1989.

- García Sáiz, María Concepción, "The Artistic Development of Casta Painting," in New World Orders, Ilona Katzew, ed. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery, 1996.

- Katzew, Ilona. "Casta Painting: Identity and Social Stratification in Colonial Mexico," New York University, 1996.

- Katzew, Ilona, ed. New World Orders: Casta Painting and Colonial Latin America. New York: Americas Society Art Gallery 1996.

- Katzew, Ilona. Casta Painting: Images of Race in Eighteenth-Century Mexico. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-300-10971-9

External links

- "Casta Paintings" An example of one of the many things that can be found in Breamore House that has attracted a lot of interest over the years. This collection of Casta paintings is believed to be the only one in United Kingdom. The collection of fourteen paintings, was commissioned for the King of Spain in 1715 and painted by Mexican artist Juan Rodríguez Juárez.

- Castas paintings and discussion on Nuestros Ranchos Genealogy of Mexico website

- Safo, Nova. "Casta Paintings: Inventing Race Through Art/Mexican Art Genre Reveals 18th-Century Attitudes on Racial Mixing." The Tavis Smiley Show. June 30, 2004.

- Soong, Roland. Racial Classifications in Latin America. 1999.