Aegirosaurus

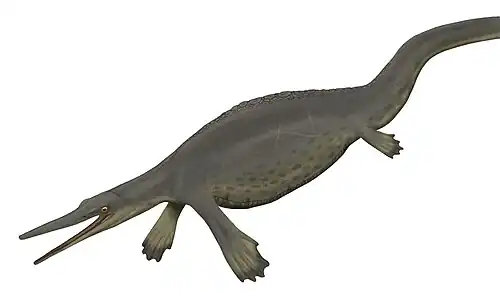

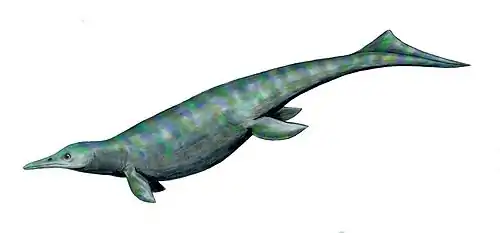

Aegirosaurus is an extinct genus of platypterygiine ophthalmosaurid ichthyosaurs known from the late Jurassic and early Cretaceous of Europe. It was originally named as a species of Ichthyosaurus.

| Aegirosaurus Temporal range: Late Jurassic-Early Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Partial specimen of Aegirosaurus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | †Ichthyosauria |

| Family: | †Ophthalmosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Platypterygiinae |

| Genus: | †Aegirosaurus Bardet & Fernandez, 2000 |

| Species: | †A. leptospondylus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Aegirosaurus leptospondylus (Wagner, 1853) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Discovery and species

Originally described by Wagner (1853) as a species of the genus Ichthyosaurus (I. leptospondylus), the species Aegirosaurus leptospondylus has had an unstable taxonomic history. It has been referred to the species Ichthyosaurus trigonus posthumus (later reclassified in the dubious genus Macropterygius) in the past, and sometimes identified with Brachypterygius extremus. In 2000, Bardet and Fernández selected a complete skeleton in a private collection as the neotype for the species I. leptospondylus, as the only other described specimen was destroyed in World War II. A second specimen from the Munich collection was referred to the same taxon. Bardet and Fernández concluded that the neotype should be assigned to a new genus, Aegirosaurus. The name means 'Aegir (teutonic god of the ocean) lizard with slender vertebrae'.[1]

Within the Ophthalmosauridae, scientists once believed Aegirosaurus was most closely related to Ophthalmosaurus.[2] However, many subsequent cladistic analyses found it is more closely related to Sveltonectes (and probably to Undorosaurus). Aegirosaurus lineage was found to include Brachypterygius and Maiaspondylus, too, and to nest within the Platypterygiinae, which is the sister taxon of Ophthalmosaurinae.[3][4]

Stratigraphic range

Aegirosaurus is known from the lower Tithonian (Upper Jurassic) of Bavaria, Germany. Its remains were discovered in the Solnhofen limestone formations, which have yielded numerous well-known fossils, such as Archaeopteryx, Compsognathus, and Pterodactylus.

In addition to its late Jurassic occurrence, Aegirosaurus has been discovered from the late Valanginian (early Cretaceous) of southeastern France (Laux-Montaux, department of Drôme; Vocontian Basin), the first diagnostic ichthyosaur recorded from the Valanginian.[5] This shows that most types of late Jurassic ichthyosaurs crossed the Jurassic-Cretaceous boundary.

Description

Ichthyosaurs are marine reptiles showing extreme adaptations to life in the water, superficially resembling fish and dolphins in overall shape.[6][7] Aegirosaurus is a medium-sized ichthyosaur. The neotype specimen is 1.77 metres (5.8 ft) long, while the destroyed holotype was estimated to have been about 2 metres (6.6 ft) long when complete. The skull of the neotype is 56 centimetres (1.84 ft) long, while that of the smaller specimen BSPHGM 1954 I 608 is approximately 30 centimetres (0.98 ft) in length.[1]

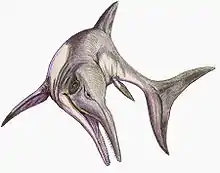

Skull

The skull of Aegirosaurus gently tapers into an elongate, thin snout that makes up 62-73% of the length of the lower jaw. Its jaws are densely packed with small teeth lacking or at most bearing very small enamel ridges. The teeth are firmly rooted in a groove. The external nares (nostril openings) are long, thin, and two-lobed in shape,[8] with one lobe protruding upwards. The orbits (eye socket) of Aegirosaurus are of medium size for an ichthyosaur, and each contains a ring of 14 bony plates (known as the sclerotic ring, which supported the eyeball) that occupies most of the space within. A flange projects outwards from above the orbit. The jugals (bones beneath the eye sockets) is short and extends in front of the orbit.[1]

The region of the skull behind the orbits is not very extensive, the length of this region being only about 6-8% of the mandible's (lower jaw) length. The postorbitals lie on top of the quadratojugals (two pairs of bones in this region), almost completely hiding them when seen from the side. Aegirosaurus also bears a pair of bones known as squamosals in its cheek region. These bones are small, triangular, and can be seen when the skull is viewed from the side. However, two pairs of bones of the skull roof, the postfrontals and supratemporals, block them from reaching the temporal fenestrae (openings located on top of the skull). The mandible is strongly built. The angulars, one pair rear mandibular bones, can be seen on the mandible's outer surface and extend as far forwards as the surangulars, another pair of bones in the same region.[1]

Postcranial skeleton

Aegirosaurus is estimated to have had around 157 vertebrae, with 52 of them being presacral (neck and trunk) vertebrae while the other 105 caudal (tail) vertebrae. The tail was bent downwards at a roughly 45 degree angle. This bend was formed by four vertebrae, with 40 caudal vertebrae in front of them and 61 behind. The vertebrae of Aegirosaurus are small and both ends of their centra (vertebral bodies) are concave. The centra are about twice as wide, and, in the case of the presacral vertebrae, tall as they are long. The diapophyses (projections from the top part of the vertebrae) flow smoothly into the neural arches (which form the top part of the neural canal). Another set of projections, the parapophyses, which are located lower than the diapophyses, are positioned towards the front of the vertebrae.[1]

The slender scapulae (shoulder blades) of Aegirosaurus are expanded at both ends and constricted at their middles.[1] The front edges of the coracoids (another paired shoulder bone) lack notches.[9] The pelvis of Aegirosaurus is composed of two bones on each side, each pubic bone and ischium (lower hip bones) having been fused into a single unit known as the puboischiatic complex. The lower end of the puboischiatic complex is over twice as wide as its upper, and the bone is not pierced by a foramen.[1]

The short, massively built humeri (upper arm bones) of Aegirosaurus have a lower ends that are wider than their upper ends.[9][1] Each humerus bears facets for three bones on its lower end, two larger ones for the radius and ulna (lower arm bones) and a smaller one in the middle[9] for the wedge-shaped intermedium (one of the carpals).[1] The radius is significantly smaller than the ulna, and the intermedium is longer from its lower to upper end than it is wide.[9] An additional bone is present in each front flipper, located in front of and slightly lower than the radius. This bone, known as an extrazeugopodial element, has an accessory digit attached to it.[8][1] In total, Aegirosaurus has six digits in each foreflipper, five of them primary digits (digits that contact the wrist).[8] The fourth digit, which contains 23 individual bones, is the longest in the foreflipper.[1]

The hindflippers are short, with the femora (thigh bones) only half the length of the humeri and smaller than the lower hip bones. There are two bones, the tibia and fibula (shin bones) that contact the lower end of each femur, and the hind flippers each bear four digits, three of them primary digits (contacting the ankle).[8][1] Both the front and hind flippers have a similar bone configuration, with the bones angular and tightly packed together further up while those further towards the flipper's tip being less tightly packed and rounder. Except for the fibulae, all of the bones in the flippers lack notches.[1]

Soft tissue

The soft tissue of the front flippers of Aegirosaurus closely follows the shape of the bones. The front flippers are elongate but narrow, with their strongly concave rear edges. The hind flippers, however, have extensive soft tissue envelopes, making them wide. A caudal fin in the shape of a crescent moon is present on the tail. Bardet and Fernández reported three types of skin impressions in the neotype: a wavy texture running parallel to the body; straight, fibrous tissue at a right angle to the ripples; and what appeared to be very small scales. This last texture was found on the upper lobe of the caudal fin, and would contradict the idea that ichthyosaurs lacked scales. However, the authors cautioned that the specimen would have to be studied using microscopes before the presence of scales on Aegirosaurus could be confirmed.[1] A study of the Aegirosaurus sp. specimen JME-SOS-08369 by Lene Delsett and colleagues in 2022, however, found it to have smooth, scaleless skin, as typical for ichthyosaurs.[10]

Palaeobiology

Tooth morphology and wear pattern suggest that Aegirosaurus belonged to the "Pierce II/ Generalist" feeding guild.[5]

References

- Bardet, N; Fernández, M (2000). "A new ichthyosaur from the Upper Jurassic lithographic limestones of Bavaria" (PDF). Journal of Paleontology. 74 (3): 503–511. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2000)074<0503:aniftu>2.0.co;2. S2CID 131190803.

- Fernández, M (2007). "Redescription and phylogenetic position of Caypullisaurus (Ichthyosauria: Ophthalmosauridae)". Journal of Paleontology. 81 (2): 368–375. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2007)81[368:rappoc]2.0.co;2. S2CID 130457040.

- Fischer, Valentin; Edwige Masure, Maxim S. Arkhangelsky and Pascal Godefroit (2011). "A new Barremian (Early Cretaceous) ichthyosaur from western Russia". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (5): 1010–1025. doi:10.1080/02724634.2011.595464. hdl:2268/92828. S2CID 86036325.

- Valentin Fischer; Michael W. Maisch; Darren Naish; Ralf Kosma; Jeff Liston; Ulrich Joger; Fritz J. Krüger; Judith Pardo Pérez; Jessica Tainsh; Robert M. Appleby (2012). "New Ophthalmosaurid Ichthyosaurs from the European Lower Cretaceous Demonstrate Extensive Ichthyosaur Survival across the Jurassic–Cretaceous Boundary". PLOS ONE. 7 (1): e29234. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...729234F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029234. PMC 3250416. PMID 22235274.

- Fischer, V.; Clement, A.; Guiomar, M.; Godefroit, P. (2011). "The first definite record of a Valanginian ichthyosaur and its implications on the evolution of post-Liassic Ichthyosauria". Cretaceous Research. 32 (2): 155–163. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.11.005. hdl:2268/79923. S2CID 45794618.

- Sander, P. M. (2000). "Ichthyosauria: their diversity, distribution, and phylogeny". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 74 (1): 1–35. doi:10.1007/BF02987949. S2CID 85352593.

- Marek, R. (2015). "Fossil Focus: Ichthyosaurs". Palaeontology Online. 5: 8.

- Maisch, M. W.; Matzke, A. T. (2000). "The Ichthyosauria". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B. 298: 1–159.

- Ji, C.; Jiang, D. Y.; Motani, R.; Rieppel, O.; Hao, W. C.; Sun, Z. Y. (2016). "Phylogeny of the Ichthyopterygia incorporating recent discoveries from South China". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (1): e1025956. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1025956. S2CID 85621052.

- Delsett, L. L.; Friis, H.; Kölbl-Ebert, M.; Hurum, J. H. (2022). "The soft tissue and skeletal anatomy of two Late Jurassic ichthyosaur specimens from the Solnhofen archipelago". PeerJ. 10: e13173. doi:10.7717/peerj.13173. PMC 8995021. PMID 35415019.