Aethia

Aethia is a genus of four small (85–300g) auklets endemic to the North Pacific Ocean, Bering Sea and Sea of Okhotsk and among some of North America's most abundant seabirds.[2] The relationships between the four true auklets remains unclear. Auklets are threatened by invasive species such as Arctic foxes (Alopex lagopus) and Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) because of their high degree of coloniality and crevice-nesting.

| Aethia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Whiskered auklet (Aethia pygmaea) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Alcidae |

| Tribe: | Aethiini |

| Genus: | Aethia Merrem, 1788 |

| Type species | |

| Alca cristatella[1] Pallas, 1769 | |

| Species | |

Taxonomy and evolution

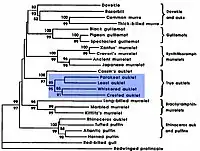

The genus Aethia occurs only in the North Pacific and adjacent waters, mainly in the Bering Sea region. Along with Cassin's auklet (Ptychoramphus aleuticus) they comprise the monophyletic tribe Aethinii. Molecular work has not yet resolved the relationship between the Aethia auklets, but the group is a sister group to Cassin's auklet, which is, in turn, a sister group to the Fraterculine auks (puffins and rhinoceros auklet).[3]

The genus Aethia did not enter into widespread use until the 1960s.[4] Initially, the auklets were placed in Alca,[5] but later reorganized into genera including: Simorhynchus,[6] Phaleris and Cyclorhynchus.[2] Cyclorhynchus is still occasionally used for the parakeet auklet.

Fossil record

The first undisputed auk fossils are from the middle Miocene (15 million years ago).[2] The first Aethia fossils date from the late Miocene (8–13 million years ago)[7] and the four extant species likely diverged rapidly about 5 million years ago.[8]

There are one or two fossil species which lived in the area of today's California during the Late Miocene: Aethia rossmoori Howard, 1968 (Monterrey Formation of Orange County), and an undescribed taxon tentatively placed in this genus. From the Pliocene there are Aethia barnesi N. A. Smith, 2013 (San Mateo Formation of San Diego County, California, and Aethia storeri N. A. Smith, 2013 (San Mateo Formation of San Diego County, California.

Species

There are four species of Aethia.

| Image | Scientific name | Common Name | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aethia pusilla | Least auklet | Alaska and Siberia |

| Aethia cristatella | Crested auklet | northern Pacific and the Bering Sea |

| Aethia pygmaea | Whiskered auklet | Aleutian Islands and on some islands off Siberia |

| Aethia psittacula | Parakeet auklet | Alaska, Kamchatka and Siberia |

Distribution

Population estimates

Censusing breeding auklets can be difficult because they nest in hidden crevices.[9] At present, population estimates are:[2]

- Least auklet - 20,000,000+

- Whiskered auklet - 100,000 - 250,000

- Crested auklet - 5,000,000 - 10,000,000

- Parakeet auklet - 1,000,000 - 2,000,000

Breeding season

Aethia auklets are endemic to the North Pacific Ocean and Sea of Okhotsk with notable Asian colonies in the Kuril Islands, Commander Islands, along the Kamchatka and Chukota Peninsulas. In North America, large colonies are in the Aleutian Islands (Buldir, Kiska, Semisopochnoi and Gareloi) to the Gulf of Alaska and north to the islands of the Bering Sea (St. Lawrence Island, Pribilof Islands, St. Matthew Island).[2]

Auklets have a high site fidelity, at both the colony and crevice level, although there can be a high divorce rate of up to 33% in least and crested auklets when both mates survive.[2]

Winter distribution

The Winter distribution of auklets is poorly known. Whiskered auklets likely winter near to breeding colonies[10] and many were reported by Aleuts to winter in the general area.[11] Auklets from the northern Bering Sea must move further south because of pack ice surrounding colonies during the winter.[2]

Breeding

Auklets are typically very social and nest in dense colonies (Parakeet auklets are more dispersed).[2] All have some form of facial ornamentation such as large crests (Whiskered and crested auklets), auricular plumes (all four species), and crested and whiskered auklets have a tangerine-scented odour[2] which may function in mate choice[12] or species recognition, although this requires more study.[13]

All Aethia auklets lay one white egg in a natural crevice and incubate for 25–36 days,[2] after which, a semi-precocial chick emerges and fledges after 25–35 days.[14] Age at first breeding is estimated at 3–5 years.[15] Colony sizes are highly variable, and range from less than 100 individuals to over 1 million, although least and crested auklets tend to nest in greater density than parakeet and whiskered auklets.[16]

Diet

The auklets are mainly planktivores, eating a variety of calanoid copepods, euphausiids and other invertebrates such as jellyfish and ctenophores. Winter diet has not been studied.[2]

Threats and conservation

Because they nest in crevices, auklets are vulnerable to predation by rats,[17] and have been extirpated from some islands that contained Arctic foxes introduced for farming.[10][18] Eradication of rats from Rat Island was completed in 2008 and 2009.[19]

The large colony at Sirius Point, Kiska Island, Alaska (perhaps the largest auklet colony in the world[2]) experienced almost complete breeding failure in 2001 and 2002 because of rat predation and disturbance[20] and has been the focus of researchers at Memorial University of Newfoundland.[21]

References

- "Alcidae". aviansystematics.org. The Trust for Avian Systematics. Retrieved 2023-07-26.

- Gaston, A.J.; Jones, I.L. (1998). The Auks: Alcidae. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-854032-8.

- Friesen, V.L.; Baker, A.J.; Piatt, J.F (1996). "Phylogenetic relationships within the Alcidae (Charadriiformes: Aves) inferred using total molecular evidence". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 13 (2): 359–367. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025595. PMID 8587501.

- Storer, R.W. 1960. Evolution of the diving birds. Proceedings of the International Ornithological Congress 12: 694–707.

- Linnaeus, C., 1758. Systema Naturae, 10th ed. Stockholm

- Stejneger, L. 1885. Results of ornithological explorations in the Commander Islands and in Kamtschatka. Bulletin of the United States National Museum No. 29.

- Warheit, Kenneth I. (October 1992). "A review of the fossil seabirds from the Tertiary of the North Pacific: plate tectonics, paleoceanography and faunal change". Paleobiology. 18 (4): 401–424. Bibcode:1992Pbio...18..401W. doi:10.1017/S0094837300010976. S2CID 130150919.

- Moum, T.; Johansen, S.; Erikstad, K.E.; Piatt, J.F. (1996). "Phylogeny and evolution of the auks (subfamily Alcinae) based on mitochondrial DNA sequences". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA. 91 (17): 7912–7916. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.17.7912. PMC 44514. PMID 8058734.

- Jones, I.L., 1992. Colony attendance of Least Auklets at St. Paul Island, Alaska: implications for population monitoring. Condor 94, 93–100.

- Williams, J.C., Byrd, G.V. and Konyukhov, N.B. 2003. Whiskered Auklets Aethia pygmaea, foxes, humans and how to right a wrong. Marine Ornithology 31:175-180.

- Murie, O.J. 1959. Fauna of the Aleutian Islands and Alaska Peninsula. North American Fauna 61:1-364.

- Jones, I.L.; Hunter, F.M. (1993). "Mutual sexual selection in a monogamous seabird". Nature. 362 (6417): 238–239. Bibcode:1993Natur.362..238J. doi:10.1038/362238a0. S2CID 4254675.

- Jones, I.L.; Hunter, F.M.; Robertson, G.J.; Fraser, G.S. (2004). "Natural variation in the sexually selected feather ornaments of Crested Auklets (Aethia cristatella) does not predict future survival". Behavioral Ecology. 15 (2): 332–337. doi:10.1093/beheco/arh018.

- Ydenberg, R.C. (1989). "Growth-mortality trade-offs and the evolution of juvenile life histories in the Alcidae". Ecology. 70 (5): 1494–1506. doi:10.2307/1938208. JSTOR 1938208.

- Jones, I.L.; Hunter, F.M.; Robertson, G.J.; Williams, J.C.; Byrd, G.V. (2007). "Covariation among demographic and climate parameters in Whiskered Auklets Aethia pygmaea". Journal of Avian Biology. 38 (4): 450–461. doi:10.1111/j.2007.0908-8857.03895.x.

- Byrd, G.V., Renner, H.M. and Renner, M. 2005. Distribution patterns and population trends of breeding seabirds in the Aleutian Islands. Fisheries Oceanography 14:139-159.

- Atkinson, I.A.E. 1985. The spread of commensal species of Rattus to oceanic islands and their effects on island avifaunas. In Moors, P.J. (eds.). 1985. Conservation of Island Birds. ICBP Technical Publication No. 3, Cambridge.

- Bailey, E.P. 1993. Introduction of foxes to Alaskan islands - history, effects on avifauna, and eradication. Fish and Wildlife Series Resource Publication 193. United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington, DC.

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2007. Restoring wildlife habitat on Rat Island. Environmental Assessment, Alaska Maritime National Wildlife Refuge, Anchorage AK. 141pp

- Major, H.L.; Jones, I.L.; Byrd, G.V.; Williams, J.C. (2006). "Assessing the effects of introduced Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) on survival and productivity of Least Auklets (Aethia pusilla)". Auk. 123 (3): 681–694. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2006)123[681:ateoin]2.0.co;2. S2CID 684091.

- "Auklets and Norway rats at Sirius Point, Kiska Island".