Oryza glaberrima

Oryza glaberrima, commonly known as African rice, is one of the two domesticated rice species.[1] It was first domesticated and grown in West Africa around 3,000 years ago.[2][3] In agriculture, it has largely been replaced by higher-yielding Asian rice (O. sativa),[2] and the number of varieties grown is declining.[1] It still persists, making up an estimated 20%[4] of rice grown in West Africa. It is now rarely sold in West African markets, having been replaced by Asian strains.[5]

| Oryza glaberrima | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Oryza |

| Species: | O. glaberrima |

| Binomial name | |

| Oryza glaberrima | |

| |

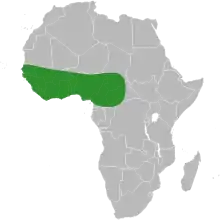

| Wild range. Cultivated range is much larger. | |

In comparison to Asian rice, African rice is hardy, pest-resistant, low-labour, and suited to a larger variety of African conditions.[1] It is described as filling, with a distinct nutty flavour.[4] It is also grown for cultural reasons; for instance, it is sacred to followers of Awasena (a traditional African religion) among the Jola people,[6] and is a heritage variety in the United States.[7]

Crossbreeding between African and Asian rice is difficult, but there exist some crosses.[8][9][10] Jones et al. 1997 and Gridley et al. 2002 provide hybrids combining glaberrima's disease resistance and sativa's yield potential.[11]

History

It is highly likely that humans have independently domesticated two different rice species. African rice is very genetically similar to wild African rice (O. barthii), as Asian rice (O. sativa) is to wild Asian rice (O. rufipogon), and these two divisions have wide genetic differences between them.

O. barthii still grows wild in Africa, in a wide variety of open habitats. The Sahara was formerly wetter, with massive paleolakes in what is now the Western Sahara. As the climate dried, the wild rice retreated and probably became increasingly domesticated as it relied on humans for irrigation. Rice growing in deeper, more permanent water became floating rice.[4]

It was domesticated about 3000 years ago[12] in the inland delta of the Upper Niger River, in what is now Mali.[1][2] It then spread through West Africa. It has also been recorded off the east coast of Africa, in the Zanzibar Archipelago.[4]

O. barthii seedheads shatter, while O. glaberrima does not shatter as much.

In the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, the Portuguese sailed to the Southern Rivers area in West Africa and wrote that the land was rich in rice. "[T]hey said they found the country covered by vast crops, with many cotton trees and large fields planted in rice ... the country looked to them as having the aspect of a pond (i.e., a marais)". The Portuguese accounts speak of the Falupo Jola, Landuma, Biafada, and Bainik growing rice. André Álvares de Almada wrote about the dike systems used for rice cultivation,[1] from which modern West African rice dike systems are descended.

African rice was brought to the Americas with the transatlantic slave trade, arriving in Brazil probably by the 1550s[3] and in the U.S. in 1784.[15] The seed was carried as provisions on slave ships,[3] and the technology and skills needed to grow it were brought by enslaved rice farmers. Newly imported African slaves were marketed for their rice-growing skills, as the high price of rice made it a major cash crop.[13] Not all Africans came to the Americas with knowledge in rice growing, due to the vast variabilities in cultures and ethnicities, but the practice of cultivation was shared throughout the Carolina plantations, which allowed the enslaved people to develop a new sense of culture and made African rice the primary source of nutrition.[16] The tolerance of African rice for brackish water meant it could be grown on coastal deltas,[14][17] as it was in West Africa.

There are numerous stories about how the rice came to North America,[18] including a slave smuggling grains in her hair[3] and a ship driven in to trade by a storm.[14][19] African rice is a rare crop in Brazil, Guyana, El Salvador and Panama, but it is still occasionally grown there.[4] There are also native South American rices, which makes it hard to recognize the arrival of African rice in histories.[3]

Asian rice came to West Africa in the late 1800s, and by the late twentieth century had substantially supplanted native African rice. However, African rice was still used in specific, often marginal habitats, and preferred for its taste.[1][4] Farmers may grow African rice to eat and Asian rice to sell, as African rice is not exported.

The 2007 food price shocks drove efforts to raise rice production. Rice-growing regions of Africa are generally net rice importers (partly due to a lack of good local rice-processing capacity) so price increases hurt.[20] Among the efforts to increase yield was the adoption of nerica cultivars, crossbred to specifications from local farmers using African rice varieties provided by local farmers.[1] These were bred during the 1990s and released in the early 21st century.[8] Results so far have been mixed; the nerica varieties are less hardy and more labour-intensive, and effects on real-world yields vary. Subsidies of nerica seeds have also been criticized for encouraging the loss of native varieties and reducing the independence of farmers.[10]

Use

With inedible husk

|

Dehusked (whole brown rice)

|

|

Multiple varieties of African rice are often grown so that the harvest is staggered. In this way, the harvest can be eaten fresh. Freshly harvested rice is moist, and can be puffed in fire, and eaten. Fried rice has a brownish color when fried; this is because of the husk which is green in color and turns brown when heated.

African rice can be prepared in much the same way as Asian rice, but has a distinct nutty flavor, for which it is favored in West Africa.[1][21] African rice grains are often reddish in colour; some varieties are strongly aromatic,[4] other, like Carolina Gold, are not at all aromatic.[15]

African rice is also used in local traditional medicine.[21]

Traits

Overall, O. glaberrima is considered a much more desirable healthier [22] choice in places like Nigeria by West African farmers where it is used to make Ofada rice because of its high nutrition content [23] despite being less popular than O. sativa cultivars (as of 2019).[12]

Appearance

African rice is a tall rice plant, usually under 120 centimetres (47 in) but up to 5 metres (16 feet) for floating varieties, which may also branch and root from higher stem nodes.[4] Generally, African rice has small, pear-shaped grain, reddish bran and green to black hulls, straight, simply-branched panicles, and short, rounded ligules. There are, however, exceptions, and it can be hard to distinguish from Asian rice.[1][4] For complete certainty, a genetic test can be used.[24]

Grain qualities

Grains are brittle.[12]

Hardiness

African rice is well adapted to the African environment. It is drought- and deep-water-resistant, and tolerates fluctuations in water depth, iron toxicity, infertile soils, severe climatic conditions, and human neglect better than Asian rice.[1][25] Some varieties also mature more quickly, and may be sown directly on higher ground, eliminating the need to transplant seedlings.[1] Most is rain-watered, and the soil is often not cultivated.[4]

African rice has profuse vegetative growth, which smothers weeds. It exhibits better resistance to various rice pests and diseases, such as blast disease, African rice gall midge (Orseolia oryzivora), parasitic nematodes (Heterodera sacchari and Meloidogyne spp.), rice stripe necrosis virus (a Benyvirus), rice yellow mottle virus, and the parasitic plant Striga.[8][25]

Yield and processing

African rices shatter more than Asian rices,[12] possibly because they have not been domesticated for as long. A few varieties of African rice are as resistant to shattering as shatter-resistant Asian varieties, but most are not; on average, about half of the grains are scattered and lost. This is why yield is lower; when the heads of African rice are bagged before they become ripe, so that the shattered grains are caught in paper bags, the yield of African rice is the same as the yield of Asian rice.[25]

Like other grains, rice may lodge, or fall over, when grain heads are full. African rice's greater height and weaker stems makes it more likely to lodge, although it also lets it survive in deep water, and makes it easier to harvest. African rice tends to elongate rapidly if completely submerged, which is not advantageous in regions prone to short floods, as it weakens the plant.[4][26]

The grains of African rice are more brittle than those of Asian rice. The grains are more likely to break during industrial polishing.[7] Broken rice is widely used in West Africa, and some cookbooks from the region will suggest manually breaking the grains for certain recipes,[27] but most broken rice eaten is from Asian rice, about 16% of which is broken in processing.

The genome of O. glaberrima has been sequenced, and was published in 2014.[2] This allowed genomic as well as physiological comparison with related species, and identified some effects of some genes.[28][29]

Breeding

African and Asian rice do not readily interpollinate, even under controlled conditions, and when they do, the offspring are very rarely fertile. Even the fertile crossbred offspring have low fertility.[8]

Crossbreeding seems to have succeeded in at least one area of Maritime Guinea, as some varieties there show crossbred genes.[9]

More recently, the nerica cultivars (new rice for Africa) have been developed using green revolution techniques like embryo rescue.[8] Over 3000 crosses were made as part of the NERICA program.[8] Breeding within the species is easier, and there are uncounted numbers of African rice varieties, although the majority may have been lost.[1] A similar crossed variety was bred in the United States in 2011,[18] and work is being done on crosses with Indian rice varieties.[8]

Cultivars

African cultivars

There are a great many varieties of African rice. In the 1960s older women in Jipalom (Ziguinchor Region, Senegal) could unhesitatingly name more than ten varieties of African rice that were no longer planted, besides the half-dozen that were then still being planted. Each woman would plant multiple different varieties, to suit varying microhabitats and to stagger the harvest.[1] A 2006 survey showed that a village typically cultivated 25 varieties of rice; an individual household would on average have 14 varieties and grow four per year;[10] this, however, is down from the seven to nine varieties per woman that was average in previous decades. Women, who are traditionally responsible for the seeds, trade them often over long-distance networks.[1]

Varieties, each with subtypes, include:[1]

- aspera (Latin: "rough")

- ebenicolorata ("ebony-colored")

- evoluta ("unfolded")

- rigida ("rigid")

- rustica ("coarse")

The cultivars the Africa Rice Center calls TOG 12303 and TOG 9300 have low shattering, and thus yields comparable with low-shattering Asian rice varieties.[25]

Scientists from the Africa Rice Center managed to cross-breed African rice with Asian rice varieties to produce a group of interspecific cultivars called New Rice for Africa (NERICA).[30]

American cultivars

Carolina Gold is an heirloom cultivar grown in the early United States, sometimes known as golden-seed rice for the colour of its grains.[15]

Long-grain gold-seed rice boasted grains 5⁄12 inch (11 mm)inch long (up 11% from 3⁄8 inch (9.5 mm)), and was brought to market by planter Joshua John Ward in the 1840s. Despite its popularity, the variety was lost in the American Civil War.[15]

Charleston Gold was released in 2011 and is a crossbreed of Carolina Gold and two breeding lines of O. s. indica called IR64[31] and IR65610-24-3-6-3-2-3 (a dwarf, fragrant breeding line), which raised the yield, shortened the stem, and added an aromatic quality to the rice.[15]

References

- Linares, Olga F. (2002-12-10). "African rice (Oryza glaberrima): History and future potential". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 99 (25): 16360–16365. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916360L. doi:10.1073/pnas.252604599. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 138616. PMID 12461173.

-

- Wendel, Jonathan F.; Jackson, Scott A.; Meyers, Blake C.; Wing, Rod A. (2016-03-01). "Evolution of plant genome architecture". Genome Biology. BioMed Central Ltd. 17 (1). doi:10.1186/s13059-016-0908-1. ISSN 1474-760X. PMC 4772531. S2CID 12325319.

- Plant Bioinformatics. Methods in Molecular Biology (MIMB). New York, NY: Humana New York, NY. 2016. p. 115–140. doi:10.1007/978-1-4939-3167-5. ISBN 978-1-4939-3166-8. ISSN 1064-3745.

- These reviews cite this research.

- Wang, Muhua; Yu, Yeisoo; Haberer, Georg; Marri, Pradeep Reddy; Fan, Chuanzhu; Goicoechea, Jose Luis; Zuccolo, Andrea; Song, Xiang; Kudrna, Dave; Ammiraju, Jetty S. S.; Cossu, Rosa Maria; Maldonado, Carlos; Chen, Jinfeng; Lee, Seunghee; Sisneros, Nick; de Baynast, Kristi; Golser, Wolfgang; Wissotski, Marina; Kim, Woojin; Sanchez, Paul; Ndjiondjop, Marie-Noelle; Sanni, Kayode; Long, Manyuan; Carney, Judith; Panaud, Olivier; Wicker, Thomas; Machado, Carlos A.; Chen, Mingsheng; Mayer, Klaus F. X.; Rounsley, Steve; Wing, Rod A. (2014-07-27). "The genome sequence of African rice (Oryza glaberrima) and evidence for independent domestication". Nature Genetics. 46 (9): 982–988. doi:10.1038/ng.3044. ISSN 1061-4036. PMC 7036042. PMID 25064006.

- Judith A. Carney (2004). "'With Grains in Her Hair': Rice in Colonial Brazil" (PDF). Slavery and Abolition. London: Frank Cass. 25 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1080/0144039042000220900. S2CID 3490844. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-11-05. Retrieved 2016-08-09.

- Plant Resources of Tropical Africa, PROTA4U database. "Oryza glaberrima Steud".

- Ikhioya, Sunny; Oritse, Godwin (2013-10-07). "Smuggled rice floods Nigerian market, as merchants suffer losses". Vanguard.

- Thiam, Pierre; Sit, Jennifer (2015). "Senegal: Modern Senegalese Recipes from the Source to the Bowl". A System of Rice Production, Broken. Lake Isle Press.

- Carney, Judith Ann (2009-06-30). Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02921-7.

- Sarla, N.; Swamy, B. P. Mallikarjuna (2005-09-25). "Oryza glaberrima: A source for the improvement of Oryza sativa". Current Science. Indian Academy of Sciences. 89 (6): 955–963. ISSN 0011-3891. Current Science Association. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- Barry, M. B.; Pham, J. L.; Noyer, J. L.; Billot, C.; Courtois, B.; Ahmadi, N. (2007-01-04). "Genetic diversity of the two cultivated rice species (O. sativa & O. glaberrima) in Maritime Guinea. Evidence for interspecific recombination". Euphytica. 154 (1–2): 127–137. doi:10.1007/s10681-006-9278-1. ISSN 0014-2336. S2CID 23798032.

- GRAIN (2009). "Nerica: another trap for small farmers in Africa" (PDF).

- Sweeney, Megan; McCouch, Susan (2007). "The Complex History of the Domestication of Rice". Annals of Botany. Oxford University Press. 100 (5): 951–957. doi:10.1093/aob/mcm128. PMC 2759204. PMID 17617555. S2CID 14266565.

- Chen, Erwang; Huang, Xuehui; Tian, Zhixi; Wing, Rod A.; Han, Bin (2019-04-29). "The Genomics of Oryza Species Provides Insights into Rice Domestication and Heterosis". Annual Review of Plant Biology. Annual Reviews. 70 (1): 639–665. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100320. ISSN 1543-5008. PMID 31035826. S2CID 140266038.

- Jean M. West. "Rice and Slavery: A Fatal Gold Seede". Slavery in America Organization. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- The Rice Diversity Project]. "Slavery on South Carolina Rice Plantations: The Migration of People and Knowledge in Early Colonial America" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-07-02. Retrieved 2016-08-09.

- Shields, David S. (2011). "Charleston Gold: A Direct Descendant of Carolina Gold" (PDF). The Rice Paper. 5 (1). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-05-13.

- Carney, Judith A. (2009-06-30). Black Rice. Harvard University Press. p. 5. doi:10.2307/j.ctvjz837d. ISBN 978-0-674-02921-7. S2CID 247120906.

- "Decline in Inland Rice Production · Forgotten Fields: Inland Rice Plantations in the South Carolina Lowcountry · Lowcountry Digital History Initiative". ldhi.library.cofc.edu. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- David S. Shields. "The Golden Seed" (PDF). Rice Paper. Vol. 5, no. 1.

- "Rice History - Carolina Plantation Rice". www.carolinaplantationrice.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- Tiamiyu, S.A.; Usman, S.A; Gbanguba, A.; Ukwungu, A.U.; Ochigbo, M.N.; Ochigbo, A.A. (2010). Assessment of quality management techniques: Toward improving competitiveness of Nigerian rice (PDF). Second Africa Rice Congress: Innovation and Partnerships to Realize Africa's Rice Potential. Bamako, Mali.

- "Oryza glaberrima (African rice)". Plants & Fungi At Kew Gardens. Retrieved 2016-08-10.

- Ogunleke, A.; Baiyegunhi, Lloyd (2019). "Effect of households' dietary knowledge on local (ofada) rice consumption in southwest Nigeria". Journal of Ethnic Foods. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 6 (1). doi:10.1186/s42779-019-0023-5. ISSN 2352-6181. S2CID 257164894.

- George, Bunmi (15 September 2016). "Ofada rice the super food". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 February 2023. despite

- Nourollah, Ahmadi (2016). "Genetic Diversity, Genetic Erosion, and Conservation of the Two Cultivated Rice Species (Oryza sativa and Oryza glaberrima) and Their Close Wild Relatives". In Ahuja, M.R.; Jain, S. Mohan (eds.). Genetic Diversity and Erosion in Plants. Sustainable Development and Biodiversity. Vol. 8. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 35–73. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-25954-3_2. ISBN 978-3-319-25953-6. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- Montcho, D.; Futakuchi, K.; Agbangla, C.; Fofana, M.; Dieng, I. (2013-01-01). "Yield loss of Oryza glaberrima caused by grain shattering under rainfed upland conditions". International Journal of Biological and Chemical Sciences. 7 (2): 535–543. doi:10.4314/ijbcs.v7i2.10. ISSN 1997-342X.

- Woolhouse, Harold William (1979). Advances in Botanical Research. Vol. 7. London: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-005907-2.

- example

- Zhang, Qun-Jie; Zhu, Ting; Xia, En-Hua; Shi, Chao; Liu, Yun-Long; Zhang, Yun; Liu, Yuan; Jiang, Wen-Kai; Zhao, You-Jie; Mao, Shu-Yan; Zhang, Li-Ping; Huang, Hui; Jiao, Jun-Ying; Xu, Ping-Zhen; Yao, Qiu-Yang; Zeng, Fan-Chun; Yang, Li-Li; Gao, Ju; Tao, Da-Yun; Wang, Yue-Ju; Bennetzen, Jeffrey L.; Gao, Li-Zhi (2014-11-18). "Rapid diversification of five Oryza AA genomes associated with rice adaptation". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (46): E4954–E4962. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111E4954Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.1418307111. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 4246335. PMID 25368197.

-

- These reviews...

- • Gaur, Pooran; Jukanti, Aravind; Varshney, Rajeev (2012). "Impact of Genomic Technologies on Chickpea Breeding Strategies". Agronomy. MDPI. 2 (3): 199–221. doi:10.3390/AGRONOMY2030199. eISSN 2073-4395. S2CID 86648608.

- • Varshney, Rajeev; Glaszmann, Jean; Leung, Hei; Ribaut, Jean (2010). "More genomic resources for less-studied crops" (PDF). Trends in Biotechnology. Cell Press. 28 (9): 452–60. doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.06.007. ISSN 0167-7799. PMID 20692061. S2CID 39342187.

- • Ali, M.; Sanchez, Paul; Yu, Si; Lorieux, Mathias; Eizenga, Georgia (2010). "Chromosome Segment Substitution Lines: A Powerful Tool for the Introgression of Valuable Genes from Oryza Wild Species into Cultivated Rice (O. sativa)". Rice. Springer Science+Business Media. 3 (4): 218–234. doi:10.1007/s12284-010-9058-3. ISSN 1939-8425. S2CID 35569020.

- ...cite this study:

- • Gutierrez, Andres; Carabali, Silvio; Giraldo, Olga; Martinez, Cesar; Correa, Fernando; Prado, Gustavo; Tohme, Joe; Lorieux, Mathias (2010). "Identification of a Rice stripe necrosis virus resistance locus and yield component QTLs using Oryza sativa × O. glaberrima introgression lines". BMC Plant Biology. BioMed Central. 10: 1–11. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-10-6. ISSN 1471-2229. PMC 2824796. PMID 20064202. S2CID 13794259.

- Jones, Monty P.; Dingkuhn, Michael; Alukosnm, Gabriel K.; Semon, Mandé (1997-03-01). "Interspecific Oryza Sativa L. × O. Glaberrima Steud. progenies in upland rice improvement". Euphytica. 94 (2): 237–246. doi:10.1023/A:1002969932224. ISSN 0014-2336. S2CID 28577400.

- Datta, Karabi; Datta, Swapan Kumar (2006). Indica rice (Oryza sativa, BR29 and IR64). Methods in Molecular Biology. Vol. 343. pp. 201–212. doi:10.1385/1-59745-130-4:201. ISBN 978-1-59745-130-7. ISSN 1064-3745. PMID 16988345.

Further reading

- Rice Origins 2 Slightly outdated National Geographic article on Carolina Gold (dead link 9 September 2019)

- Shields, David S; Carolina Gold Rice Foundation (2010). The golden seed: writings on the history and culture of Carolina gold rice. United States: Douglas W. Bostick for the Carolina Gold Rice Foundation. ISBN 978-0-9829792-1-1.

- Fields-Black, Edda L. 2008. Deep Roots: Rice Farmers in West Africa and the African Diaspora. (Blacks in the Diaspora.) Bloomington: Indiana University Press.