Rice

Rice is the seed of the grass species Oryza sativa (Asian rice) or, less commonly, O. glaberrima (African rice). The name wild rice is usually used for species of the genera Zizania and Porteresia, both wild and domesticated, although the term may also be used for primitive or uncultivated varieties of Oryza.

As a cereal grain, domesticated rice is the most widely consumed staple food for over half of the world's human population,[1] particularly in Asia and Africa. It is the agricultural commodity with the third-highest worldwide production, after sugarcane and maize.[2] Since sizable portions of sugarcane and maize crops are used for purposes other than human consumption, rice is the most important food crop with regard to human nutrition and caloric intake, providing more than one-fifth of the calories consumed worldwide by humans.[3] There are many varieties of rice, and culinary preferences tend to vary regionally.

The traditional method for cultivating rice is flooding the fields while, or after, setting the young seedlings. This simple method requires sound irrigation planning, but it reduces the growth of less robust weed and pest plants that have no submerged growth state, and deters vermin. While flooding is not mandatory for the cultivation of rice, all other methods of irrigation require higher effort in weed and pest control during growth periods and a different approach for fertilizing the soil.

Rice, a monocot, is normally grown as an annual plant, although in tropical areas it can survive as a perennial and can produce a ratoon crop for up to 30 years.[4] Rice cultivation is well-suited to countries and regions with low labor costs and high rainfall, as it is labor-intensive to cultivate and requires ample water. However, rice can be grown practically anywhere, even on a steep hill or mountain area with the use of water-controlling terrace systems. Although its parent species are native to Asia and certain parts of Africa, centuries of trade and exportation have made it commonplace in many cultures worldwide. Production and consumption of rice is estimated to have been responsible for 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2010.

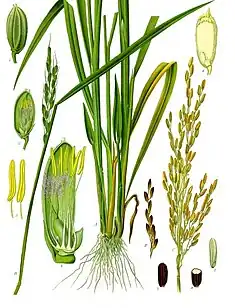

Characteristics

The rice plant can grow to 1–1.8 m (3–6 ft) tall, occasionally more depending on the variety and soil fertility. It has long, slender leaves 50–100 cm (20–40 in) long and 2–2.5 cm (3⁄4–1 in) broad. The small wind-pollinated flowers are produced in a branched arching to pendulous inflorescence 30–50 cm (12–20 in) long. The edible seed is a grain (caryopsis) 5–12 mm (3⁄16–15⁄32 in) long and 2–3 mm (3⁄32–1⁄8 in) thick.

Rice is a cereal crop belonging to the family Poecae. Rice being a tropical crop can be grown during the two distinct seasons (dry and wet) of the year provided that moisture is made available to the crop.[5]

Small wind-pollinated flowers

Small wind-pollinated flowers

Food

Rice is commonly consumed as food around the world. The varieties of rice are typically classified as long-, medium-, and short-grained.[6] The grains of long-grain rice (high in amylose) tend to remain intact after cooking; medium-grain rice (high in amylopectin) becomes more sticky. Medium-grain rice is used for sweet dishes, for risotto in Italy, and many rice dishes, such as arròs negre, in Spain. Some varieties of long-grain rice that are high in amylopectin, known as Thai Sticky rice, are usually steamed.[7] A stickier short-grain rice is used for sushi;[8] the stickiness allows rice to hold its shape when cooked.[9] Short-grain rice is used extensively in Japan,[10] including to accompany savoury dishes.[11]

Rice-growing environments

Rice growth and production are affected by: the environment, soil properties, biotic conditions, and cultural practices. Environmental factors include rainfall and water, temperature, photoperiod, solar radiation and, in some instances, tropical storms. Soil factors refer to soil type and their position in uplands or lowlands. Biotic factors deal with weeds, insects, diseases, and crop varieties.[12]

Rice can be grown in different environments, depending upon water availability.[13] Generally, rice does not thrive in a waterlogged area, yet it can survive and grow herein[14] and it can survive flooding.[15]

- Lowland, rainfed, which is drought prone, favors medium depth; waterlogged, submergence, and flood prone

- Lowland, irrigated, grown in both the wet season and the dry season

- Deep water or floating rice

- Coastal wetland

- Upland rice (also known as hill rice or Ghaiya rice)

History of cultivation

The current scientific consensus, based on archaeological and linguistic evidence, is that Oryza sativa rice was first domesticated in the Yangtze River basin in China 13,500 to 8,200 years ago.[16][17][18][19] Cultivation, migration and trade spread rice around the world—first to much of east Asia, and then further abroad, and eventually to the Americas as part of the Columbian exchange. The now less common Oryza glaberrima rice was independently domesticated in Africa around 3,000 years ago.[20]

Since its spread, rice has become a global staple crop important to food security and food cultures around the world. Local varieties of Oryza sativa have resulted in over 40,000 cultivars of various types. More recent changes in agricultural practices and breeding methods as part of the Green Revolution and other transfers of agricultural technologies has led to increased production in recent decades.[21]Production and commerce

| Rice production – 2020 | |

|---|---|

| Country | Millions of tonnes |

| 211.9 | |

| 178.3 | |

| 54.9 | |

| 54.6 | |

| 42.8 | |

| 30.2 | |

| 25.1 | |

| 19.3 | |

| 11.1 | |

| 11.0 | |

| World | 756.7 |

| Source: FAOSTAT of the United Nations[22] | |

Production

.svg.png.webp)

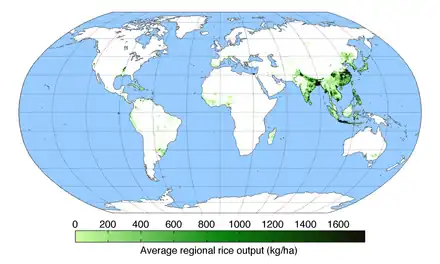

In 2020, world production of paddy rice was 756.7 million metric tons (834.1 million short tons),[24] led by China and India with a combined 52% of this total.[2] Other major producers were Bangladesh, Indonesia and Vietnam. The five major producers accounted for 72% of total production, while the top fifteen producers accounted for 91% of total world production in 2017. Developing countries account for 95% of the total production.[25]

Rice is a major food staple and a mainstay for the rural population and their food security. It is mainly cultivated by small farmers in holdings of less than one hectare. Rice is also a wage commodity for workers in the cash crop or non-agricultural sectors. Rice is vital for the nutrition of much of the population in Asia, as well as in Latin America and the Caribbean and in Africa; it is central to the food security of over half the world population.

Many rice grain producing countries have significant losses post-harvest at the farm and because of poor roads, inadequate storage technologies, inefficient supply chains and farmer's inability to bring the produce into retail markets dominated by small shopkeepers. A World Bank – FAO study claims 8% to 26% of rice is lost in developing nations, on average, every year, because of post-harvest problems and poor infrastructure. Some sources claim the post-harvest losses exceed 40%.[25][26] Not only do these losses reduce food security in the world, the study claims that farmers in developing countries such as China, India and others lose approximately US$89 billion of income in preventable post-harvest farm losses, poor transport, the lack of proper storage and retail. One study claims that if these post-harvest grain losses could be eliminated with better infrastructure and retail network, in India alone enough food would be saved every year to feed 70 to 100 million people.[27]

Processing

The seeds of the rice plant are first milled using a rice huller to remove the chaff (the outer husks of the grain) (see: rice hulls). At this point in the process, the product is called brown rice. The milling may be continued, removing the bran, i.e., the rest of the husk and the germ, thereby creating white rice. White rice, which keeps longer, lacks some important nutrients; moreover, in a limited diet which does not supplement the rice, brown rice helps to prevent the disease beriberi.

Either by hand or in a rice polisher, white rice may be buffed with glucose or talc powder (often called polished rice, though this term may also refer to white rice in general), parboiled, or processed into flour. White rice may also be enriched by adding nutrients, especially those lost during the milling process. While the cheapest method of enriching involves adding a powdered blend of nutrients that will easily wash off (in the United States, rice which has been so treated requires a label warning against rinsing), more sophisticated methods apply nutrients directly to the grain, coating the grain with a water-insoluble substance which is resistant to washing.

In some countries, a popular form, parboiled rice (also known as converted rice and easy-cook rice[28]) is subjected to a steaming or parboiling process while still a brown rice grain. The parboil process causes a gelatinisation of the starch in the grains. The grains become less brittle, and the color of the milled grain changes from white to yellow. The rice is then dried, and can then be milled as usual or used as brown rice. Milled parboiled rice is nutritionally superior to standard milled rice, because the process causes nutrients from the outer husk (especially thiamine) to move into the endosperm, so that less is subsequently lost when the husk is polished off during milling. Parboiled rice has an additional benefit in that it does not stick to the pan during cooking, as happens when cooking regular white rice. This type of rice is eaten in parts of India and countries of West Africa are also accustomed to consuming parboiled rice.

Rice bran, called nuka in Japan, is a valuable commodity in Asia and is used for many daily needs. It is a moist, oily inner layer which is heated to produce oil. It is also used as a pickling bed in making rice bran pickles and takuan.

Raw rice may be ground into flour for many uses, including making many kinds of beverages, such as amazake, horchata, rice milk, and rice wine. Rice does not contain gluten, so is suitable for people on a gluten-free diet.[29] Rice can be made into various types of noodles. Raw, wild, or brown rice may also be consumed by raw-foodist or fruitarians if soaked and sprouted (usually a week to 30 days – gaba rice).

Processed rice seeds must be boiled or steamed before eating. Boiled rice may be further fried in cooking oil or butter (known as fried rice), or beaten in a tub to make mochi.

Rice is a good source of protein and a staple food in many parts of the world, but it is not a complete protein: it does not contain all of the essential amino acids in sufficient amounts for good health, and should be combined with other sources of protein, such as nuts, seeds, beans, fish, or meat.[30]

Rice, like other cereal grains, can be puffed (or popped). This process takes advantage of the grains' water content and typically involves heating grains in a special chamber. Further puffing is sometimes accomplished by processing puffed pellets in a low-pressure chamber. The ideal gas law means either lowering the local pressure or raising the water temperature results in an increase in volume prior to water evaporation, resulting in a puffy texture. Bulk raw rice density is about 0.9 g/cm3. It decreases to less than one-tenth that when puffed.

Rice processing

Rice processing

A: Rice with chaff

B: Brown rice

C: Rice with germ

D: White rice with bran residue

E: Polished

(1): Chaff

(2): Bran

(3): Bran residue

(4): Cereal germ

(5): Endosperm

Harvesting, drying and milling

Unmilled rice, known as "paddy" (Indonesia and Malaysia: padi; Philippines, palay), is usually harvested when the grains have a moisture content of around 25%. In most Asian countries, where rice is almost entirely the product of smallholder agriculture, harvesting is carried out manually, although there is a growing interest in mechanical harvesting. Harvesting can be carried out by the farmers themselves, but is also frequently done by seasonal labor groups. Harvesting is followed by threshing, either immediately or within a day or two. Again, much threshing is still carried out by hand but there is an increasing use of mechanical threshers. Subsequently, paddy needs to be dried to bring down the moisture content to no more than 20% for milling.

A familiar sight in several Asian countries is paddy laid out to dry along roads. However, in most countries the bulk of drying of marketed paddy takes place in mills, with village-level drying being used for paddy to be consumed by farm families. Mills either sun dry or use mechanical driers or both. Drying has to be carried out quickly to avoid the formation of molds. Mills range from simple hullers, with a throughput of a couple of tonnes a day, that simply remove the outer husk, to enormous operations that can process 4 thousand metric tons (4.4 thousand short tons) a day and produce highly polished rice. A good mill can achieve a paddy-to-rice conversion rate of up to 72% but smaller, inefficient mills often struggle to achieve 60%. These smaller mills often do not buy paddy and sell rice but only service farmers who want to mill their paddy for their own consumption.

Rice combine harvester in Chiba Prefecture, Japan

Rice combine harvester in Chiba Prefecture, Japan After the harvest, rice straw is gathered in the traditional way from small paddy fields in Mae Wang District, Thailand

After the harvest, rice straw is gathered in the traditional way from small paddy fields in Mae Wang District, Thailand.jpg.webp)

Drying rice in Peravoor, India

Drying rice in Peravoor, India

Distribution

Because of the importance of rice to human nutrition and food security in Asia, the domestic rice markets tend to be subject to considerable state involvement. While the private sector plays a leading role in most countries, agencies such as BULOG in Indonesia, the NFA in the Philippines, VINAFOOD in Vietnam and the Food Corporation of India are all heavily involved in purchasing of paddy from farmers or rice from mills and in distributing rice to poorer people. BULOG and NFA monopolise rice imports into their countries while VINAFOOD controls all exports from Vietnam.[31]

Trade

World trade figures are much smaller than those for production, as less than 8% of rice produced is traded internationally.[32] In economic terms, the global rice trade was a small fraction of 1% of world mercantile trade. Many countries consider rice as a strategic food staple, and various governments subject its trade to a wide range of controls and interventions.

Developing countries are the main players in the world rice trade, accounting for 83% of exports and 85% of imports. While there are numerous importers of rice, the exporters of rice are limited. Just five countries—Thailand, Vietnam, China, the United States and India—in decreasing order of exported quantities, accounted for about three-quarters of world rice exports in 2002.[25] However, this ranking has been rapidly changing in recent years. In 2010, the three largest exporters of rice, in decreasing order of quantity exported were Thailand, Vietnam and India. By 2012, India became the largest exporter of rice with a 100% increase in its exports on year-to-year basis, and Thailand slipped to third position.[33][34] Together, Thailand, Vietnam and India accounted for nearly 70% of the world rice exports.

The primary variety exported by Thailand and Vietnam were Jasmine rice, while exports from India included aromatic Basmati variety. China, an exporter of rice in the early 2000s, had become a net importer of rice by 2010.[32][35] According to a USDA report, the world's largest exporters of rice in 2012 were India (9.75 million metric tons (10.75 million short tons)), Vietnam (7 million metric tons (7.7 million short tons)), Thailand (6.5 million metric tons (7.2 million short tons)), Pakistan (3.75 million metric tons (4.13 million short tons)) and the United States (3.5 million metric tons (3.9 million short tons)).[36]

Major importers usually include Nigeria, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Iraq, Malaysia, the Philippines, Brazil and some African and Persian Gulf countries. In common with other West African countries, Nigeria is actively promoting domestic production. However, its very heavy import duties (110%) open it to smuggling from neighboring countries.[37] Parboiled rice is particularly popular in Nigeria. Although China and India are the two largest producers of rice in the world, both countries consume the majority of the rice produced domestically, leaving little to be traded internationally.

Yield records

The average world yield for rice was 4.3 metric tons per hectare (1.9 short tons per acre), in 2010. Australian rice farms were the most productive in 2010, with a nationwide average of 10.8 metric tons per hectare (4.8 short tons per acre).[38]

Yuan Longping of China National Hybrid Rice Research and Development Center set a world record for rice yield in 2010 at 19 metric tons per hectare (8.5 short tons per acre) on a demonstration plot. In 2011, this record was reportedly surpassed by an Indian farmer, Sumant Kumar, with 22.4 metric tons per hectare (10.0 short tons per acre) in Bihar, although this claim has been disputed by both Yuan and India's Central Rice Research Institute. These efforts employed newly developed rice breeds and System of Rice Intensification (SRI), a recent innovation in rice farming.[39][40][41][42]

Worldwide consumption

| Food consumption of rice in 2013 (millions of metric tons of paddy equivalent)[43] | |

|---|---|

| 162.4 | |

| 130.4 | |

| 50.4 | |

| 40.3 | |

| 19.9 | |

| 17.6 | |

| 11.5 | |

| 11.4 | |

As of 2013, world food consumption of rice was 565.6 million metric tons (623.5 million short tons) of paddy equivalent (377,283 metric tons (415,883 short tons) of milled equivalent), while the largest consumers were China consuming 162.4 million metric tons (179.0 million short tons) of paddy equivalent (28.7% of world consumption) and India consuming 130.4 million metric tons (143.7 million short tons) of paddy equivalent (23.1% of world consumption).[43]

Between 1961 and 2002, per capita consumption of rice increased by 40% worldwide.[44] Rice is the most important crop in Asia. In Cambodia, for example, 90% of the total agricultural area is used for rice production.[45] Per capita, Bangladesh ranks as the country with the highest rice consumption, followed by Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam and Indonesia.[46]

U.S. rice consumption has risen sharply over the past 25 years, fueled in part by commercial applications such as beer production.[47] Almost one in five adult Americans now report eating at least half a serving of white or brown rice per day.[48]

Environmental impacts

.jpg.webp)

Climate change

The worldwide production of rice accounts for more greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) in total than that of any other plant food.[49] It was estimated in 2021 to be responsible for 30% of agricultural methane emissions and 11% of agricultural nitrous oxide emissions.[50] Methane release is caused by long-term flooding of rice fields, inhibiting the soil from absorbing atmospheric oxygen, a process causing anaerobic fermentation of organic matter in the soil.[51] A 2021 study estimated that rice contributed 2 billion tonnes of anthropogenic greenhouse gases in 2010,[49] of the 47 billion total.[52] The study added up GHG emissions from the entire lifecycle, including production, transportation, and consumption, and compared the global totals of different foods.[53] The total for rice was half the total for beef.[49]

A 2010 study found that, as a result of rising temperatures and decreasing solar radiation during the later years of the 20th century, the rice yield growth rate has decreased in many parts of Asia, compared to what would have been observed had the temperature and solar radiation trends not occurred.[54][55] The yield growth rate had fallen 10–20% at some locations. The study was based on records from 227 farms in Thailand, Vietnam, Nepal, India, China, Bangladesh, and Pakistan. The mechanism of this falling yield was not clear, but might involve increased respiration during warm nights, which expends energy without being able to photosynthesize. More detailed analysis of rice yields by the International Rice Research Institute forecast 20% reduction in yields in Asia per degree Celsius of temperature rise. Rice becomes sterile if exposed to temperatures above 35 °C (95 °F) for more than one hour during flowering and consequently produces no grain.[56][57]

Water usage

Rice requires slightly more water to produce than other grains.[58] Rice production uses almost a third of Earth's fresh water.[59] Water outflows from rice fields through transpiration, evaporation, seepage, and percolation.[60] It is estimated that it takes about 2,500 litres (660 US gal) of water need to be supplied to account for all of these outflows and produce 1 kilogram (2 lb 3 oz) of rice.[60]

Pests and diseases

Rice pests are animals which have the potential to reduce the yield or value of the rice crop (or of rice seeds); plants are described as weeds, while microbes are described as pathogens, disease-causing organisms.[61] Rice pests include insects, nematodes, rodents, and birds. A variety of factors can contribute to pest outbreaks, including climatic factors, improper irrigation, the overuse of insecticides and high rates of nitrogen fertilizer application.[62] Weather conditions also contribute to pest outbreaks. For example, rice gall midge and army worm outbreaks tend to follow periods of high rainfall early in the wet season, while thrips outbreaks are associated with drought.[63]

Pests

.jpg.webp)

Major rice insect pests include: the brown planthopper (BPH),[64] several species of stemborers—including those in the genera Scirpophaga and Chilo,[65] the rice gall midge,[66] several species of rice bugs,[67] notably in the genus Leptocorisa,[68] defoliators such as the rice: leafroller, hispa and grasshoppers.[69] The fall army worm, a species of Lepidoptera, also targets and causes damage to rice crops.[70] Rice weevils attack stored produce.

Several nematode species infect rice crops, causing diseases such as ufra (Ditylenchus dipsaci), white tip disease (Aphelenchoide bessei), and root knot disease (Meloidogyne graminicola). Some nematode species such as Pratylenchus spp. are most damaging to upland rice of all parts of the world. Rice root nematode (Hirschmanniella oryzae) is a migratory endoparasite which on higher inoculum levels leads to complete destruction of a rice crop. Beyond being obligate parasites, they decrease the vigor of plants and increase the plants' susceptibility to other pests and diseases.[71][72]

Other pests include the apple snail (Pomacea canaliculata), panicle rice mite, rats,[73] and the weed Echinochloa crus-galli.[74]

Diseases

Rice blast, caused by the fungus Magnaporthe grisea (syn. M. oryzae, Pyricularia oryzae),[75] is the most significant disease affecting rice cultivation. It and bacterial leaf streak (caused by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae) are perennially the two worst rice diseases worldwide, and such is their importance – and the importance of rice – that they are both among the worst 10 diseases of all plants.[76] A 2010 review reported clones for quantitative disease resistance in plants.[77] The plant responds to the blast pathogen by releasing jasmonic acid, which then cascades into the activation of further downstream metabolic pathways which produce the defense response.[78] This accumulates as methyl-jasmonic acid.[78] The pathogen responds by synthesizing an oxidizing enzyme which prevents this accumlation and its resulting alarm signal.[78] OsPii-2 was discovered by Fujisaki et al., 2017.[79] It is a nucleotide-binding leucine-rich repeat receptor (NB-LRR, NLR), an immunoreceptor.[79] It includes an NOI domain (NO3-induced) which binds rice's own Exo70-F3 protein.[79] This protein is a target of the M. oryzae effector AVR-Pii and so this allows the NLR to monitor for Mo's attack against that target.[79]

Other major fungal and bacterial rice diseases include sheath blight (caused by Rhizoctonia solani), false smut (Ustilaginoidea virens), bacterial panicle blight (Burkholderia glumae),[80] sheath rot (Sarocladium oryzae), and bakanae (Fusarium fujikuroi).[81] Viral diseases exist, such as rice ragged stunt (vector: BPH), and tungro (vector: Nephotettix spp).[82] Many viral diseases, especially those vectored by planthoppers and leafhoppers, are major causes of losses across the world.[83] There is also an ascomycete fungus, Cochliobolus miyabeanus, that causes brown spot disease in rice.[84][85][81]

The gene OsSWEET13 produces the molecular target of the Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae effector PthXo2. [86] Some cultivars carry resistance alleles.[86]

Integrated pest management

Crop protection scientists are trying to develop rice pest management techniques which are sustainable. In other words, to manage crop pests in such a manner that future crop production is not threatened.[87] Sustainable pest management is based on four principles: biodiversity, host plant resistance, [88] landscape ecology, and hierarchies in a landscape—from biological to social.[89] At present, rice pest management includes cultural techniques, pest-resistant rice varieties,[88] and pesticides (which include insecticide). Increasingly, there is evidence that farmers' pesticide applications are often unnecessary, and even facilitate pest outbreaks.[90][91][92][93] By reducing the populations of natural enemies of rice pests,[94] misuse of insecticides can actually lead to pest outbreaks.[95] The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) demonstrated in 1993 that an 87.5% reduction in pesticide use can lead to an overall drop in pest numbers.[96] IRRI also conducted two campaigns in 1994 and 2003, respectively, which discouraged insecticide misuse and smarter pest management in Vietnam.[97][98]

Rice plants produce their own chemical defenses to protect themselves from pest attacks. Some synthetic chemicals, such as the herbicide 2,4-D, cause the plant to increase the production of certain defensive chemicals and thereby increase the plant's resistance to some types of pests.[99] Conversely, other chemicals, such as the insecticide imidacloprid, can induce changes in the gene expression of the rice that cause the plant to become more susceptible to attacks by certain types of pests.[100] 5-Alkylresorcinols are chemicals that can also be found in rice.[101]

Botanicals, so-called "natural pesticides", are used by some farmers in an attempt to control rice pests. Botanicals include extracts of leaves, or a mulch of the leaves themselves. Some upland rice farmers in Cambodia spread chopped leaves of the bitter bush (Chromolaena odorata) over the surface of fields after planting. This practice probably helps the soil retain moisture and thereby facilitates seed germination. Farmers also claim the leaves are a natural fertilizer and helps suppress weed and insect infestations.[102]

Among rice cultivars, there are differences in the responses to, and recovery from, pest damage.[67][103][88] Many rice varieties have been selected for resistance to insect pests.[104][105][88] Therefore, particular cultivars are recommended for areas prone to certain pest problems.[88] The genetically based ability of a rice variety to withstand pest attacks is called resistance. Three main types of plant resistance to pests are recognized as nonpreference, antibiosis, and tolerance.[106] Nonpreference (or antixenosis) describes host plants which insects prefer to avoid; antibiosis is where insect survival is reduced after the ingestion of host tissue; and tolerance is the capacity of a plant to produce high yield or retain high quality despite insect infestation.[107]

Over time, the use of pest-resistant rice varieties selects for pests that are able to overcome these mechanisms of resistance. When a rice variety is no longer able to resist pest infestations, resistance is said to have broken down. Rice varieties that can be widely grown for many years in the presence of pests and retain their ability to withstand the pests are said to have durable resistance. Mutants of popular rice varieties are regularly screened by plant breeders to discover new sources of durable resistance.[106][108]

Parasitic weeds

Rice is parasitized by the hemiparasitic eudicot weed Striga hermonthica,[109] which is of local importance for this crop.

Ecotypes and cultivars

While most rice is bred for crop quality and productivity, there are varieties selected for characteristics such as texture, smell, and firmness. There are four major categories of rice worldwide: indica, japonica, aromatic and glutinous. The different varieties of rice are not considered interchangeable, either in food preparation or agriculture, so as a result, each major variety is a completely separate market from other varieties. It is common for one variety of rice to rise in price while another one drops in price.[110]

Rice cultivars also fall into groups according to environmental conditions, season of planting, and season of harvest, called ecotypes. Some major groups are the Japan-type (grown in Japan), "buly" and "tjereh" types (Indonesia); sali (or aman—main winter crop), ahu (also aush or ghariya, summer), and boro (spring) (Bengal and Assam).[111][112] Cultivars exist that are adapted to deep flooding, and these are generally called "floating rice".[113]

The largest collection of rice cultivars is at the International Rice Research Institute[114] in the Philippines, with over 100,000 rice accessions[115] held in the International Rice Genebank.[116] Rice cultivars are often classified by their grain shapes and texture. For example, Thai Jasmine rice is long-grain and relatively less sticky, as some long-grain rice contains less amylopectin than short-grain cultivars. Chinese restaurants often serve long-grain as plain unseasoned steamed rice though short-grain rice is common as well. Japanese mochi rice and Chinese sticky rice are short-grain. Chinese people use sticky rice which is properly known as "glutinous rice" (note: glutinous refer to the glue-like characteristic of rice; does not refer to "gluten") to make zongzi. The Japanese table rice is a sticky, short-grain rice. Japanese sake rice is another kind as well.

Indian rice cultivars include long-grained and aromatic Basmati (ਬਾਸਮਤੀ) (grown in the North), long and medium-grained Patna rice, and in South India (Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka) short-grained Sona Masuri (also called as Bangaru theegalu). In the state of Tamil Nadu, the most prized cultivar is ponni which is primarily grown in the delta regions of the Kaveri River. Kaveri is also referred to as ponni in the South and the name reflects the geographic region where it is grown. In the Western Indian state of Maharashtra, a short grain variety called Ambemohar is very popular. This rice has a characteristic fragrance of Mango blossom.

Aromatic rices have definite aromas and flavors; the most noted cultivars are Thai fragrant rice, Basmati, Patna rice, Vietnamese fragrant rice, and a hybrid cultivar from America, sold under the trade name Texmati. Both Basmati and Texmati have a mild popcorn-like aroma and flavor. In Indonesia, there are also red and black cultivars.

High-yield cultivars of rice suitable for cultivation in Africa and other dry ecosystems, called the new rice for Africa (NERICA) cultivars, have been developed. It is hoped that their cultivation will improve food security in West Africa.

Draft genomes for the two most common rice cultivars, indica and japonica, were published in April 2002. Rice was chosen as a model organism for the biology of grasses because of its relatively small genome (~430 megabase pairs). Rice was the first crop with a complete genome sequence.[117]

On December 16, 2002, the UN General Assembly declared the year 2004 the International Year of Rice. The declaration was sponsored by more than 40 countries.

Varietal development has ceremonial and historical significance for some cultures (see § Culture below). The Thai kings have patronised rice breeding since at least the reign of Chulalongkorn,[118][119] and his great-great-grandson Vajiralongkorn released five particular rice varieties to celebrate his coronation.[120]

Biotechnology

High-yielding varieties

The high-yielding varieties are a group of crops created intentionally during the Green Revolution to increase global food production. This project enabled labor markets in Asia to shift away from agriculture, and into industrial sectors. The first "Rice Car", IR8 was produced in 1966 at the International Rice Research Institute which is based in the Philippines at the University of the Philippines' Los Baños site. IR8 was created through a cross between an Indonesian variety named "Peta" and a Chinese variety named "Dee Geo Woo Gen."[121]

Scientists have identified and cloned many genes involved in the gibberellin signaling pathway, including GAI1 (Gibberellin Insensitive) and SLR1 (Slender Rice). Disruption of gibberellin signaling can lead to significantly reduced stem growth leading to a dwarf phenotype. Photosynthetic investment in the stem is reduced dramatically as the shorter plants are inherently more stable mechanically. Assimilates become redirected to grain production, amplifying in particular the effect of chemical fertilizers on commercial yield. In the presence of nitrogen fertilizers, and intensive crop management, these varieties increase their yield two to three times.[122]

Golden rice

Golden rice is a variety of rice (Oryza sativa) produced through genetic engineering to biosynthesize beta-carotene, a precursor of vitamin A, in the edible parts of the rice.[123][124] It is intended to produce a fortified food to be grown and consumed in areas with a shortage of dietary vitamin A. Vitamin A deficiency causes xerophthalmia, a range of eye conditions from night blindness to more severe clinical outcomes such as keratomalacia and corneal scars, and permanent blindness. Additionally, vitamin A deficiency also increases risk of mortality from measles and diarrhea in children. In 2013, the prevalence of deficiency was the highest in sub-Saharan Africa (48%; 25–75), and South Asia (44%; 13–79).[125]

Although golden rice has met significant opposition from environmental and anti-globalisation activists, more than 100 Nobel laureates in 2016 encouraged use of genetically modified golden rice which can produce up to 23 times as much beta-carotene as the original golden rice.[126][127][128]Expression of human proteins

Ventria Bioscience has genetically modified rice to express lactoferrin, lysozyme which are proteins usually found in breast milk, and human serum albumin, These proteins have antiviral, antibacterial, and antifungal effects.[129]

Rice containing these added proteins can be used as a component in oral rehydration solutions which are used to treat diarrheal diseases, thereby shortening their duration and reducing recurrence. Such supplements may also help reverse anemia.[130]

Flood-tolerant rice

Due to the varying levels that water can reach in regions of cultivation, flood tolerant varieties have long been developed and used. Flooding is an issue that many rice growers face, especially in South and South East Asia where flooding annually affects 20 million hectares (49 million acres).[131] Standard rice varieties cannot withstand stagnant flooding of more than about a week,[132] mainly as it disallows the plant access to necessary requirements such as sunlight and essential gas exchanges, inevitably leading to plants being unable to recover.[131] In the past, this has led to massive losses in yields, such as in the Philippines, where in 2006, rice crops worth $65 million were lost to flooding.[133] Recently developed cultivars seek to improve flood tolerance.

Drought-tolerant rice

Drought represents a significant environmental stress for rice production, with 19–23 million hectares (47–57 million acres) of rainfed rice production in South and South East Asia often at risk.[134][135] Under drought conditions, without sufficient water to afford them the ability to obtain the required levels of nutrients from the soil, conventional commercial rice varieties can be severely affected—for example, yield losses as high as 40% have affected some parts of India, with resulting losses of around US$800 million annually.[136]

The International Rice Research Institute conducts research into developing drought-tolerant rice varieties, including the varieties 5411 and Sookha dhan, currently being employed by farmers in the Philippines and Nepal respectively.[135] In addition, in 2013 the Japanese National Institute for Agrobiological Sciences led a team which successfully inserted the DEEPER ROOTING 1 (DRO1) gene, from the Philippine upland rice variety Kinandang Patong, into the popular commercial rice variety IR64, giving rise to a far deeper root system in the resulting plants.[136] This facilitates an improved ability for the rice plant to derive its required nutrients in times of drought via accessing deeper layers of soil, a feature demonstrated by trials which saw the IR64 + DRO1 rice yields drop by 10% under moderate drought conditions, compared to 60% for the unmodified IR64 variety.[136][137]

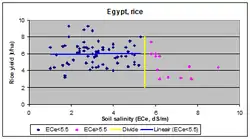

Salt-tolerant rice

Soil salinity poses a major threat to rice crop productivity, particularly along low-lying coastal areas during the dry season.[134][138] For example, roughly 1 million hectares (2.5 million acres) of the coastal areas of Bangladesh are affected by saline soils.[139] These high concentrations of salt can severely affect rice plants' normal physiology, especially during early stages of growth, and as such farmers are often forced to abandon these otherwise potentially usable areas.[140][141]

Progress has been made, however, in developing rice varieties capable of tolerating such conditions; the hybrid created from the cross between the commercial rice variety IR56 and the wild rice species Oryza coarctata is one example.[142] O. coarctata is capable of successful growth in soils with double the limit of salinity of normal varieties, but lacks the ability to produce edible rice.[142] Developed by the International Rice Research Institute, the hybrid variety can utilise specialised leaf glands that allow for the removal of salt into the atmosphere. It was initially produced from one successful embryo out of 34,000 crosses between the two species; this was then backcrossed to IR56 with the aim of preserving the genes responsible for salt tolerance that were inherited from O. coarctata.[140] Extensive trials are planned prior to the new variety being available to farmers by approximately 2017–18.[140]

Environment-friendly rice

Producing rice in paddies is harmful for the environment due to the release of methane by methanogenic bacteria. These bacteria live in the anaerobic waterlogged soil, and live off nutrients released by rice roots. Researchers have recently reported in Nature that putting the barley gene SUSIBA2 into rice creates a shift in biomass production from root to shoot (above ground tissue becomes larger, while below ground tissue is reduced), decreasing the methanogen population, and resulting in a reduction of methane emissions of up to 97%. Apart from this environmental benefit, the modification also increases the amount of rice grains by 43%, which makes it a useful tool in feeding a growing world population.[144][145]

Model organism

Rice is used as a model organism for investigating the molecular mechanisms of meiosis and DNA repair in higher plants. Meiosis is a key stage of the sexual cycle in which diploid cells in the ovule (female structure) and the anther (male structure) produce haploid cells that develop further into gametophytes and gametes. So far, 28 meiotic genes of rice have been characterized.[146] Studies of rice gene OsRAD51C showed that this gene is necessary for homologous recombinational repair of DNA, particularly the accurate repair of DNA double-strand breaks during meiosis.[147] Rice gene OsDMC1 was found to be essential for pairing of homologous chromosomes during meiosis,[148] and rice gene OsMRE11 was found to be required for both synapsis of homologous chromosomes and repair of double-strand breaks during meiosis.[149]

In human culture

Rice plays an important role in certain religions and popular beliefs. In many cultures, relatives scatter rice over the bride and groom in a wedding ceremony.[150] In Malay weddings, rice features in multiple special wedding foods such as "sweet glutinous rice, buttered rice, [and] yellow glutinous rice".[151] The pounded rice ritual is conducted during weddings in Nepal. The bride gives a leafplate full of pounded rice to the groom after he requests it politely from her.[152] In the Philippines rice wine, popularly known as tapuy, is used for important occasions such as weddings, rice harvesting ceremonies and other celebrations.[153]

Dewi Sri is the traditional rice goddess of the Javanese, Sundanese, and Balinese people in Indonesia. Most rituals involving Dewi Sri are associated with the mythical origin attributed to the rice plant, the staple food of the region.[154][155]

A 2014 study of Han Chinese communities found that a history of farming rice makes cultures more psychologically interdependent, whereas a history of farming wheat makes cultures more independent.[156]

A Royal Ploughing Ceremony is held in certain Asian countries to mark the beginning of the rice planting season. It is still honored in the kingdoms of Cambodia[157][158] and Thailand.[159] The 2,600-year-old tradition – begun by Śuddhodana in Kapilavastu – was revived in the republic of Nepal in 2017 after a lapse of a few years.[160]

See also

- Artificial rice

- Glutinous rice

- List of dried foods

- List of rice cultivars

- List of rice dishes

- Maratelli rice

- Mushroom production on rice straw

- Leaf Color Chart

- Post-harvest losses

- Puffed rice

- Rice Belt

- Rice bran oil

- Rice bread

- Rice wine

- Rice writing

- Rijsttafel

- Risotto

- Straw

- System of Rice Intensification

- Texas rice production

- Upland rice

- Wild rice

- Direct seeded rice

References

- Abstract, "Rice feeds more than half the world's population."

- "Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists), Rice (paddy), 2018". FAOSTAT (UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database). 2020. Archived from the original on May 11, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- Smith, Bruce D. (1998) The Emergence of Agriculture. Scientific American Library, New York, ISBN 0-7167-6030-4.

- "The Rice Plant and How it Grows". International Rice Research Institute. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009.

- Kawure, S.; Garba, Aa; Fagam, As; Shuaibu, Ym; Sabo, Mu; Bala, Ra (December 31, 2022). "Performance of Lowland Rice (Oryza sativa L.) as Influenced by Combine Effect of Season and Sowing Pattern in Zigau". Journal of Rice Research and Developments. 5 (2). doi:10.36959/973/440. S2CID 256799161.

- Fine Cooking, ed. (February 25, 2008). "Guide to Rice". Fine Cooking. Archived from the original on October 16, 2014. Retrieved July 24, 2014.

- Loha-unchit, K. "White Sticky Rice – Kao Niow". Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- America's Test Kitchen (October 6, 2020). The Best of America's Test Kitchen 2021: Best Recipes, Equipment Reviews, and Tastings. America's Test Kitchen. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-948703-40-6.

- Simmons, Marie (March 10, 2009). The Amazing World of Rice: with 150 Recipes for Pilafs, Paellas, Puddings, and More. HarperCollins. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-06-187543-4.

- Foreign Crops and Markets. United States Department of Agriculture, Foreign Agricultural Service. 1928. p. 850.

- Alford, Jeffrey; Duguid, Naomi (January 1, 2003). Seductions of Rice. Artisan. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-57965-234-0.

- Verheye, Willy H., ed. (2010). "Growth and Production of Rice". Soils, Plant Growth and Crop Production Volume II. EOLSS Publishers. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-84826-368-0.

- "IRRI Rice Knowledge Bank". Archived from the original on May 22, 2004. Retrieved April 20, 2013.

- "More rice with less water" (PDF). Cornell University. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 26, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- "Plants capable of surviving flooding". Uu.nl. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Normile, Dennis (1997). "Yangtze seen as earliest rice site". Science. 275 (5298): 309–310. doi:10.1126/science.275.5298.309. S2CID 140691699.

- Vaughan, DA; Lu, B; Tomooka, N (2008). "The evolving story of rice evolution". Plant Science. 174 (4): 394–408. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.01.016. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- Harris, David R. (1996). The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia. Psychology Press. p. 565. ISBN 978-1-85728-538-3.

- Zhang, Jianping; Lu, Houyuan; Gu, Wanfa; Wu, Naiqin; Zhou, Kunshu; Hu, Yayi; Xin, Yingjun; Wang, Can; Kashkush, Khalil (December 17, 2012). "Early Mixed Farming of Millet and Rice 7800 Years Ago in the Middle Yellow River Region, China". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e52146. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...752146Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052146. PMC 3524165. PMID 23284907.

- Choi, Jae Young (March 7, 2019). "The complex geography of domestication of the African rice Oryza glaberrima". PLOS Genetics. 15 (3): e1007414. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007414. PMC 6424484. PMID 30845217.

- "Is basmati rice healthy?". K-agriculture. April 4, 2023. Archived from the original on April 4, 2023. Retrieved April 4, 2023.

- "Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists), Rice (paddy), 2019". FAOSTAT (UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database). 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2021.

- World Food and Agriculture – Statistical Yearbook 2021. United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 2021. doi:10.4060/cb4477en. ISBN 978-92-5-134332-6. S2CID 240163091. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- "Faostat". FAOSTAT (UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database). Archived from the original on May 11, 2017. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- "Sustainable rice production for food security". United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 2003. Archived from the original on June 15, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- "MISSING FOOD: The Case of Postharvest Grain Losses in Sub-Saharan Africa" (PDF). The World Bank. April 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 23, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- Basavaraja, H.; Mahajanashetti, S.B.; Udagatti, Naveen C. (2007). "Economic Analysis of Post-harvest Losses in Food Grains in India: A Case Study of Karnataka" (PDF). Agricultural Economics Research Review. 20: 117–26. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 22, 2012. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- "Types of rice". Rice Association. Archived from the original on August 2, 2018. Retrieved August 2, 2018.

- Penagini, Francesca; Dilillo, Dario; Meneghin, Fabio; Mameli, Chiara; Fabiano, Valentina; Zuccotti, Gian (November 18, 2013). "Gluten-Free Diet in Children: An Approach to a Nutritionally Adequate and Balanced Diet". Nutrients. MDPI AG. 5 (11): 4553–4565. doi:10.3390/nu5114553. ISSN 2072-6643.

- Wu, Jianguo G.; Shi, Chunhai; Zhang, Xiaoming (2002). "Estimating the amino acid composition in milled rice by near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy". Field Crops Research. Elsevier BV. 75 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1016/s0378-4290(02)00006-0. ISSN 0378-4290.

- Shahidur Rashid, Ashok Gulari and Ralph Cummings Jnr (eds) (2008). From Parastatals to Private Trade. International Food Policy Research Institute and Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-8815-8

- Cendrowski, Scott (August 12, 2013). "The Rice Rush". Forbes (paper): 9–10.

- Chilkoti, A. (October 30, 2012). "India and the Price of Rice". The Financial Times. London. Archived from the original on January 20, 2013.

- Childs, N. "Rice Outlook 2012/2013" (PDF). US Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 20, 2013.

- "World Rice Trade". United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). November 2011. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- "India is world's largest rice exporter: USDA". The Financial Express. October 29, 2012. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013.

- "Shareholders call for intensified consultation on Nigerian rice sector trade". Agritrade. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014.

- "FAOSTAT: Production-Crops, 2010 data". United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 2011. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015.

- Yuan, Longping (2010). "A Scientist's Perspective on Experience with SRI in China for Raising the Yields of Super Hybrid Rice" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 20, 2011.

- "Indian farmer sets new world record in rice yield". The Philippine Star. December 18, 2011. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2014.

- "Grassroots heroes lead Bihar's rural revolution". India Today. January 10, 2012. Archived from the original on January 3, 2013.

- "Chinese whispers over rice record - Scientist questions nalanda farmer paddy yield". The Telegraph. February 23, 2013. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- FAOSTAT. "Food Balance Sheets > Commodity Balances > Crops Primary Equivalent". Archived from the original on April 2, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2019.

- Gnanamanickam, Samuel (2009). Biological Control of Rice Diseases. Springer. p. 5. ISBN 978-9048124640.

- Puckridge, Don (2004). The Burning of the Rice. Temple House Pty. ISBN 978-1-877059-73-5. Archived from the original on March 31, 2014.

- "Rice Consumption per Capita".

- United States Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service. "Briefing Rooms: Rice". Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- Batres-Marquez, S.P.; Jensen, H.H. (July 2005). Rice Consumption in the United States: New Evidence from Food Consumption Surveys (Report). Iowa State University. Archived from the original on May 28, 2010. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- "Meat accounts for nearly 60% of all greenhouse gases from food production, study finds". The Guardian. September 13, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- Gupta, Khushboo; Kumar, Raushan; Baruah, Kushal Kumar; Hazarika, Samarendra; Karmakar, Susmita; Bordoloi, Nirmali (June 2021). "Greenhouse gas emission from rice fields: a review from Indian context". Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 28 (24): 30551–30572. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-13935-1. PMID 33905059. S2CID 233403787.

- Neue, H.U. (1993). "Methane emission from rice fields: Wetland rice fields may make a major contribution to global warming". BioScience. 43 (7): 466–73. doi:10.2307/1311906. JSTOR 1311906. Archived from the original on January 15, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2008.

- Charles, Krista. "Food production emissions make up more than a third of global total". New Scientist. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- Xu, Xiaoming; Sharma, Prateek; Shu, Shijie; Lin, Tzu-Shun; Ciais, Philippe; Tubiello, Francesco N.; Smith, Pete; Campbell, Nelson; Jain, Atul K. (September 2021). "Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods=". Nature Food. 2 (9): 724–732. doi:10.1038/s43016-021-00358-x. hdl:2164/18207. ISSN 2662-1355. PMID 37117472. S2CID 240562878.

- Welch, Jarrod R.; Vincent, Jeffrey R.; Auffhammer, Maximilian; Moya, Piedad F.; Dobermann, Achim; Dawe, David (August 9, 2010). "Rice yields in tropical/subtropical Asia exhibit large but opposing sensitivities to minimum and maximum temperatures". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107 (33): 14562–14567. doi:10.1073/pnas.1001222107. ISSN 0027-8424.

- Black, R. (August 9, 2010). "Rice yields falling under global warming". BBC News: Science & Environment. Archived from the original on April 5, 2018. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- Singh, S.K. (2016). "Climate Change: Impact on Indian Agriculture & its Mitigation". Journal of Basic and Applied Engineering Research. 3 (10): 857–859.

- Rao, Prakash; Patil, Y. (2017). Reconsidering the Impact of Climate Change on Global Water Supply, Use, and Management. IGI Global. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-5225-1047-5.

- "Virtual Water Trade – Proceedings of the International Expert Meeting on Virtual Water Trade" (PDF). p. 108. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 3, 2014.

- "How better rice could save lives: A second green revolution". The Economist. Archived from the original on October 10, 2014. Retrieved October 6, 2014.

- "How much water does rice use?". ResearchGate. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- Jahn, G.C.; Litsinger, J.A.; Chen, Y.; Barrion, A.T. (2007). "Integrated Pest Management of Rice: Ecological Concepts". In Koul, Opender; Cuperus, Gerrit W. (eds.). Ecologically Based Integrated Pest Management. CABI (Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International). pp. 315–366. ISBN 978-1-84593-064-6.

- Jahn, Gary C.; Almazan, Liberty P.; Pacia, Jocelyn B. (2005). "Effect of Nitrogen Fertilizer on the Intrinsic Rate of Increase of Hysteroneura setariae (Thomas) (Homoptera: Aphididae) on Rice (Oryza sativa L.)". Environmental Entomology. 34 (4): 938. doi:10.1603/0046-225X-34.4.938. S2CID 1941852.

- Douangboupha, B.; Khamphoukeo, K.; Inthavong, S.; Schiller, J.M.; Jahn, G.C. (2006). "Chapter 17: Pests and diseases of the rice production systems of Laos" (PDF). In Schiller, J.M.; Chanphengxay, M.B.; Linquist, B.; Rao, S.A. (eds.). Rice in Laos. Los Baños, Philippines: International Rice Research Institute. pp. 265–281. ISBN 978-971-22-0211-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 3, 2012.

- Preap, V.; Zalucki, M.P.; Jahn, G.C. (2006). "Brown planthopper outbreaks and management" (PDF). Cambodian Journal of Agriculture. 7 (1): 17–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 9, 2022.

- "IRRI Rice insect pest factsheet: Stem borer". Rice Knowledge Bank. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014.

- Benett, J.; Bentur, J.C.; Pasula, I.C.; Krishnaiah, K. (eds) (2004). New approaches to gall midge resistance in rice. International Rice Research Institute and Indian Council of Agricultural Research, ISBN 971-22-0198-8.

- Jahn, Gary C.; Domingo, I.; Almazan, M.L.; Pacia, J. (December 2004). "Effect of rice bug Leptocorisa oratorius (Hemiptera: Alydidae) on rice yield, grain quality, and seed viability". Journal of Economic Entomology. 97 (6): 1923–1927. doi:10.1603/0022-0493-97.6.1923. PMID 15666746. S2CID 23278521.

- Jahn, GC; Domingo, I; Almazan, ML; Pacia, J. (December 2004). "Effect of rice bug Leptocorisa oratorius (Hemiptera: Alydidae) on rice yield, grain quality, and seed viability". Journal of Economic Entomology. 97 (6): 1923–1927. doi:10.1603/0022-0493-97.6.1923. PMID 15666746. S2CID 23278521.

- "Knowledge Bank". Archived from the original on July 4, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- "fall armyworm, Spodoptera frugiperda (J.E. Smith)". University of Florida entnemdept.ufl.edu. Archived from the original on October 2, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- Jairajpuri, M. Shamim. (2019). Nematode pests of rice. CRC Press.

- Prasad, J. S.; Panwar, M. S.; Rao, Y. S. "Nematode Pests of Crops". In Bhatti, D. S.; Walia, R. K. (eds.). Nematode Pests of Rice. Delhi: CBS. pp. 43–61. ISBN 9789123901067.

- Singleton, G.; Hinds, L.; Leirs, H.; and Zhang, Zh. (Eds.) (1999) "Ecologically-based rodent management" ACIAR, Canberra. Ch. 17, pp. 358–71 ISBN 1-86320-262-5.

- Pheng S.; Khiev B.; Pol C.; Jahn G.C. (2001). "Response of two rice cultivars to the competition of Echinochloa crus-gali (L.) P. Beauv". International Rice Research Institute Notes. 26 (2): 36–37. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved November 13, 2019.

- Dean, Ralph A.; Talbot, Nicholas J.; Ebbole, Daniel J.; et al. (April 2005). "The genome sequence of the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea". Nature. 434 (7036): 980–986. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..980D. doi:10.1038/nature03449. PMID 15846337.

- p. 214, "Rice blast (caused by the fungal pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae) and bacterial blight (caused by the bacterial pathogen Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae) are the most devastating rice diseases (119) and are among the 10 most important fungal and bacterial diseases in plants (32, 95). Owing to their scientific and economic importance, both pathosystems have been the focus of concentrated study over the past two decades, and they are now advanced molecular models for plant fungal and bacterial diseases."

- St.Clair, Dina (2010). "Quantitative Disease Resistance and Quantitative Resistance Loci in Breeding". Annual Review of Phytopathology. 48: 247–68. doi:10.1146/annurev-phyto-080508-081904. ISSN 0066-4286. PMID 19400646.

- Motoyama, Takayuki; Yun, Choong-Soo; Osada, Hiroyuki (2021). "Biosynthesis and biological function of secondary metabolites of the rice blast fungus Pyricularia oryzae". Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. 48 (9–10). doi:10.1093/jimb/kuab058. PMC 8788799. PMID 34379774.

- Marchal, Clemence; Michalopoulou, Vassiliki A.; Zou, Zhou; Cevik, Volkan; Sarris, Panagiotis F. (2022). "Show me your ID: NLR immune receptors with integrated domains in plants". Essays in Biochemistry. 66 (5): 527–539. doi:10.1042/ebc20210084. PMC 9528084. PMID 35635051.

- p. 214, "...other diseases, including rice sheath blight (caused by the fungal pathogen Rhizoctonia solani), false smut (caused by the fungal pathogen Ustilaginoidea virens), bacterial leaf streak (caused by X. oryzae pv. oryzicola), bacterial panicle blight (Burkholderia glumae), are emerging globally as important rice diseases (53, 72, 180) (Figure 1)."

- p. 214, Table 1: Important fungal and bacterial diseases in rice.

- "IRRI Rice Diseases factsheets". Knowledgebank.irri.org. Archived from the original on October 14, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Hibino, H. (1996). "Biology and epidemiology of rice viruses". Annual Review of Phytopathology. Annual Reviews. 34 (1): 249–274. doi:10.1146/annurev.phyto.34.1.249. PMID 15012543.

- "Rice Brown Spot: essential data". CBWinfo.com. Archived from the original on February 13, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- "Cochliobolus". Invasive.org. May 4, 2010. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Zhou, Junhui; Peng, Zhao; Long, Juying; Sosso, Davide; Liu, Bo; Eom, Joon-Seob; Huang, Sheng; Liu, Sanzhen; Vera Cruz, Casiana; Frommer, Wolf B.; White, Frank F.; Yang, Bing (2015). "Gene targeting by the TAL effector PthXo2 reveals cryptic resistance gene for bacterial blight of rice". The Plant Journal. 82 (4): 632–643. doi:10.1111/tpj.12838. PMID 25824104. S2CID 29633821.

- Jahn, Gary C.; Khiev. B.; Pol, C.; Chhorn, N.; Pheng, S.; Preap, V. (2001). "Developing sustainable pest management for rice in Cambodia". In Suthipradit S.; Kuntha C.; Lorlowhakarn, S.; Rakngan, J. (eds.). Sustainable Agriculture: Possibility and Direction. Bangkok (Thailand): National Science and Technology Development Agency. pp. 243–258.

- "Rice Varieties & Management Tips" (PDF). Louisiana State University Agricultural Center. November 24, 2020. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020.

- Savary, S.; Horgan, F.; Willocquet, L.; Heong (2012). "A review of principles for sustainable pest management in rice". Crop Protection. 32: 54. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2011.10.012.

- Jahn, Gary C.; Pheng, S.; Khiev, B.; Pol, C. (1996). Farmers' pest management and rice production practices in Cambodian lowland rice. Cambodia-IRRI-Australia Project, Baseline Survey Report No. 6. CIAP (Report). Phnom Penh, Cambodia.

- "Bangladeshi farmers banish insecticides". SCIDEV.net. July 30, 2004. Archived from the original on January 26, 2008. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- IRRI.org on YouTube (November 20, 2006). Retrieved on May 13, 2012.

- Wang, Li-Ping; Shen, Jun; Ge, Lin-Quan; Wu, Jin-Cai; Yang, Guo-Qin; Jahn, Gary C. (2010). "Insecticide-induced increase in the protein content of male accessory glands and its effect on the fecundity of females in the brown planthopper Nilaparvata lugens Stål (Hemiptera: Delphacidae)". Crop Protection. 29 (11): 1280. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2010.07.009.

- Jahn, Gary C. (1992). "Rice pest control and effects on predators in Thailand". Insecticide & Acaricide Tests. 17: 252–53. doi:10.1093/iat/17.1.252.

- Cohen, J.E.; Schoenly, K.; Heong, K.L.; Justo, H.; Arida, G.; Barrion, A.T.; Litsinger, J A. (1994). "A Food-Web Approach to Evaluating the Effect of Insecticide Spraying on Insect Pest Population-Dynamics in a Philippine Irrigated Rice Ecosystem". Journal of Applied Ecology. 31- (4): 747–63. doi:10.2307/2404165. JSTOR 2404165.

- Hamilton, Henry Sackville (January 18, 2008). "The pesticide paradox". Archived from the original on January 19, 2012.

- "Three Gains, Three Reductions". Ricehoppers.net. October 12, 2010. Archived from the original on August 20, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- "No Early Spray" (PDF). ricehoppers.net. April 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 23, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Xin, Zhaojun; Yu, Zhaonan; Erb, Matthias; et al. (April 2012). "The broad-leaf herbicide 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid turns rice into a living trap for a major insect pest and a parasitic wasp". The New Phytologist. 194 (2): 498–510. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04057.x. PMID 22313362.

- Cheng, Yao; Shi, Zhao-Peng; Jiang, Li-Ben; Ge, Lin-Quan; Wu, Jin-Cai; Jahn, Gary C. (March 2012). "Possible connection between imidacloprid-induced changes in rice gene transcription profiles and susceptibility to the brown plant hopper Nilaparvatalugens Stål (Hemiptera: Delphacidae)". Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 102–531 (3): 213–219. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2012.01.003. PMC 3334832. PMID 22544984.

- Suzuki, Yoshikatsu; Kurano, M.; Esumi, Y.; Yamaguchi, I.; Doi, Y. (December 2003). "Biosynthesis of 5-alkylresorcinol in rice: incorporation of a putative fatty acid unit in the 5-alkylresorcinol carbon chain". Bioorganic Chemistry. 31 (6): 437–452. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2003.08.003. PMID 14613765.

- Jahn, Gary C.; Pol, C.; Khiev B.; Pheng, S.; Chhorn, N. (1999). Farmer's pest management and rice production practices in Cambodian upland and deepwater rice. Cambodia-IRRI-Australia Project, Baseline Survey Rpt No. 7 (Report).

- Khiev, B.; Jahn, G.C.; Pol, C.; Chhorn N. (2000). "Effects of simulated pest damage on rice yields". IRRN. 25 (3): 27–28. Archived from the original on December 3, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- Brar, D.S.; Khush, G.S. (2003). "Utilization of Wild Species of Genus Oryza in Rice Improvement". In Nanda, J.S.; Sharma, S.D. (eds.). Monograph on Genus Oryza. Plymouth. Enfield, UK: Science Publishers. pp. 283–309.

- Sangha, J.S.; Chen, Y.H.; Kaur, J.; Khan, Wajahatullah; Abduljaleel, Zainularifeen; Alanazi, Mohammed S.; et al. (February 2013). "Proteome Analysis of Rice (Oryza sativa L.) Mutants Reveals Differentially Induced Proteins during Brown Planthopper (Nilaparvata lugens) Infestation". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 14 (2): 3921–3945. doi:10.3390/ijms14023921. PMC 3588078. PMID 23434671.

- Sangha, Jatinder Singh; Chen, Yolanda H.; Palchamy, Kadirvel; Jahn, Gary C.; Maheswaran, M.; Adalla, Candida B.; Leung, Hei (April 2008). "Categories and inheritance of resistance to Nilaparvata lugens (Hemiptera: Delphacidae) in mutants of indica rice 'IR64'". Journal of Economic Entomology. 101 (2): 575–583. doi:10.1603/0022-0493(2008)101[575:CAIORT]2.0.CO;2. PMID 18459427. S2CID 39941837.

- Kogan, M.; Ortman, E. F. (1978). "Antixenosis a new term proposed to defined to describe Painter's "non-preference" modality of resistance". Bulletin of the Entomological Society of America. 24: 175–76. doi:10.1093/besa/24.2.175.

- Liu, L.; Van Zanten, L.; Shu, Q.Y.; Maluszynski, M. (2004). "Officially released mutant varieties in China". Mutat. Breed. Rev. 14 (1): 64.

- Yoshida, Satoko; Maruyama, Shinichiro; Nozaki, Hisayoshi; Shirasu, Ken (May 2010). "Horizontal gene transfer by the parasitic plant Striga hermonthica". Science. 328 (5982): 1128. Bibcode:2010Sci...328.1128Y. doi:10.1126/science.1187145. PMID 20508124. S2CID 39376164.

- "The U.S. Rice Export Market" (PDF). USDA. November 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 13, 2015.

- Morinaga, T. (1968). "Origin and geographical distribution of Japanese rice" (PDF). Trop. Agric. Res. Ser. 3: 1–15. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 5, 2013. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- Kabir, S.M. (2012). "Rice". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, A.A. (eds.). Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- "Rice". Cgiar.org. Archived from the original on May 16, 2012. Retrieved May 13, 2012.

- "Home". Irri.org. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- "The International Rice Genebank – conserving rice". IRRI.org. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012.

- Jackson, M.T. (September 1997). "Conservation of rice genetic resources: the role of the International Rice Genebank at IRRI". Plant Molecular Biology. 35 (1–2): 61–67. doi:10.1023/A:1005709332130. PMID 9291960. S2CID 3360337.

- Gillis, J. (August 11, 2005). "Rice Genome Fully Mapped". Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "History". กระทรวงเกษตรและสหกรณ์ [Ministry of Agriculture and Cooperatives]. Archived from the original on November 17, 2021. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- "Rice Breeding and R&D Policies in Thailand". Food and Fertilizer Technology Center Agricultural Policy Platform (FFTC-AP). April 26, 2018. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- "Five rice varieties launched in honour of Royal Coronation". The Nation. May 7, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- "Rice Varieties". Archived from the original on July 13, 2006. Retrieved July 13, 2006.. IRRI Knowledge Bank.

- Yamaguchi, S. (2008). "Gibberellin metabolism and its regulation". Annual Review of Plant Biology. 59 (1): 225–251. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092804. PMID 18173378.

- Kettenburg AJ, Hanspach J, Abson DJ, Fischer J (2018). "From disagreements to dialogue: unpacking the Golden Rice debate". Sustain Sci. 13 (5): 1469–82. doi:10.1007/s11625-018-0577-y. PMC 6132390. PMID 30220919.

- Ye X, Al-Babili S, Klöti A, Zhang J, Lucca P, Beyer P, Potrykus I (January 2000). "Engineering the provitamin A (beta-carotene) biosynthetic pathway into (carotenoid-free) rice endosperm". Science. 287 (5451): 303–5. Bibcode:2000Sci...287..303Y. doi:10.1126/science.287.5451.303. PMID 10634784. S2CID 40258379.

- Stevens GA, Bennett JE, Hennocq Q, Lu Y, De-Regil LM, et al. (September 2015). "Trends and mortality effects of vitamin A deficiency in children in 138 low-income and middle-income countries between 1991 and 2013: a pooled analysis of population-based surveys". Lancet Glob Health. 3 (9): e528–36. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00039-X. PMID 26275329. S2CID 4671055.

- Paine JA, Shipton CA, Chaggar S, Howells RM, Kennedy MJ, et al. (April 2005). "Improving the nutritional value of Golden Rice through increased pro-vitamin A content". Nat Biotechnol. 23 (4): 482–7. doi:10.1038/nbt1082. PMID 15793573. S2CID 632005.

- Tang G, Qin J, Dolnikowski GG, Russell RM, Grusak MA (June 2009). "Golden Rice is an effective source of vitamin A". Am J Clin Nutr. 89 (6): 1776–83. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27119. PMC 2682994. PMID 19369372.

- Datta SK, Datta K, Parkhi V, Rai M, Baisakh N, et al. (2007). "Golden rice: introgression, breeding, and field evaluation". Euphytica. 154 (3): 271–78. doi:10.1007/s10681-006-9311-4. S2CID 39594178.

- Marris, E. (May 18, 2007). "Rice with human proteins to take root in Kansas". Nature. doi:10.1038/news070514-17. S2CID 84688423.

- Bethell, D.R.; Huang, J. (June 2004). "Recombinant human lactoferrin treatment for global health issues: iron deficiency and acute diarrhea". Biometals. 17 (3): 337–342. doi:10.1023/B:BIOM.0000027714.56331.b8. PMID 15222487. S2CID 3106602.

- Debrata, Panda; Sarkar, Ramani Kumar (2012). "Role of Non-Structural Carbohydrate and its Catabolism Associated with Sub 1 QTL in Rice Subjected to Complete Submergence". Experimental Agriculture. 48 (4): 502–12. doi:10.1017/S0014479712000397. S2CID 86192842.

- "Swarna Sub1: flood resistant rice variety". The Hindu. 2011. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- ""Climate change-ready rice". International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Archived from the original on October 28, 2012. Retrieved October 31, 2013.

- "Drought, submergence and salinity management". International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- ""Climate change-ready rice". International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). Archived from the original on March 14, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- Palmer, N. (2013). "Newly-discovered rice gene goes to the root of drought resistance". Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved September 29, 2013.

- "Roots breakthrough for drought resistant rice". Phys.org. 2013. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- "Rice Breeding Course, Breeding for salt tolerance in rice, on line". International Rice Research Institute. Archived from the original on May 5, 2017.

- "Fredenburg, P. (2007). "Less salt, please". irri.org. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- ""Wild parent spawns super salt tolerant rice". International Rice Research Institute (IRRI). 2013. Archived from the original on July 1, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- Ferrer, B. (2012). "Do rice and salt go together?". irri.org. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- ""Breakthrough in salt-resistant rice research—single baby rice plant may hold the future to extending rice farming". Integrated Breeding Platform (IBP). 2013. Archived from the original on November 2, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2013.

- "On line collection of salt tolerance data of agricultural crops obtained from measurements in farmers' fields". www.waterlog.info. Archived from the original on August 24, 2017.

- Su, J.; Hu, C.; Yan, X.; et al. (July 2015). "Expression of barley SUSIBA2 transcription factor yields high-starch low-methane rice". Nature. 523 (7562): 602–606. Bibcode:2015Natur.523..602S. doi:10.1038/nature14673. PMID 26200336. S2CID 4454200.

- Gerry, C. (August 9, 2015). "Feeding the World One Genetically Modified Tomato at a Time: A Scientific Perspective". SITN. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved September 11, 2015.

- Luo, Qiong; Li, Yafei; Shen, Yi; Cheng, Zhukuan (March 2014). "Ten years of gene discovery for meiotic event control in rice". Journal of Genetics and Genomics=Yi Chuan Xue Bao. 41 (3): 125–137. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2014.02.002. PMID 24656233.

- Tang, Ding; Miao, Chunbo; Li, Yafei; Wang, Hongjun; Liu, Xiaofei; Yu, Hengxiu; Cheng, Zhukuan (2014). "OsRAD51C is essential for double-strand break repair in rice meiosis". Frontiers in Plant Science. 5: 167. doi:10.3389/fpls.2014.00167. PMC 4019848. PMID 24847337.

- Deng, Z.Y.; Wang, T. (September 2007). "OsDMC1 is required for homologous pairing in Oryza sativa". Plant Molecular Biology. 65 (1–2): 31–42. doi:10.1007/s11103-007-9195-2. PMID 17562186. S2CID 33673421.

- Ji, Jianhui; Tang, Ding; Wang, Mo; Li, Yafei; Zhang, Lei; Wang, Kejian; et al. (October 2013). "MRE11 is required for homologous synapsis and DSB processing in rice meiosis". Chromosoma. 122 (5): 363–376. doi:10.1007/s00412-013-0421-1. PMID 23793712. S2CID 17962445.

- Ahuja, Subhash C.; Ahuja, Uma (2006). "Rice in religion and tradition" (PDF). 2nd International Rice Congress.

- Muhammad, Rosmaliza; Zahari, Mohd Salehuddin Mohd; Ramly, Alina Shuhaida Muhammad; Ahmad, Roslina (2013). "The Roles and Symbolism of Foods in Malay Wedding Ceremony". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. Elsevier BV. 101: 268–276. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.200. ISSN 1877-0428.

- Ahearn, Laura M. (2011). Living Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 3.

- unspecified (2011). Tapuy Cookbook & Cocktails. Philippine Rice Research Institute.

- "Early Mythology – Dewi Sri". Sunda.org. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- "(Indonesian) Mitos Nyi Pohaci/Sanghyang Asri/Dewi Sri". My.opera.com. March 1, 2008. Archived from the original on February 23, 2014. Retrieved August 26, 2012.

- Talhelm, T.; Zhang, X.; Oishi, S.; Shimin, C.; Duan, D.; Lan, X.; Kitayama, S. (May 2014). "Large-scale psychological differences within China explained by rice versus wheat agriculture". Science. 344 (6184): 603–608. Bibcode:2014Sci...344..603T. doi:10.1126/science.1246850. PMID 24812395. S2CID 206552838.

- "Cambodia marks beginning of farming season with royal ploughing ceremony". Xinhua. March 21, 2017. Archived from the original on May 3, 2018. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- "Ceremony Predicts Good Year". Khmer Times. May 23, 2016. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- "Thailand king cancels ceremonies as COVID surges". Nikkei Asia. May 4, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

- Sen, S. (July 2, 2019). "Ancient royal paddy planting ceremony marked". The Himalayan Times. Retrieved December 6, 2021.

Further reading

- Liu, Wende; Liu, Jinling; Triplett, Lindsay; Leach, Jan E.; Wang, Guo-Liang (August 4, 2014). "Novel insights into rice innate immunity against bacterial and fungal pathogens". Annual Review of Phytopathology. Annual Reviews. 52 (1): 213–241. doi:10.1146/annurev-phyto-102313-045926. PMID 24906128. S2CID 9244874.

- Deb, D. (October 2019). "Restoring Rice Biodiversity". Scientific American. 321 (4): 54–61.

India originally possessed some 110,000 landraces of rice with diverse and valuable properties. These include enrichment in vital nutrients and the ability to withstand flood, drought, salinity or pest infestations. The Green Revolution covered fields with a few high-yielding varieties, so that roughly 90 percent of the landraces vanished from farmers' collections. High-yielding varieties require expensive inputs. They perform abysmally on marginal farms or in adverse environmental conditions, forcing poor farmers into debt.

- Singh, B.N. (2018). Global Rice Cultivation & Cultivars. New Delhi: Studium Press. ISBN 978-1-62699-107-1. Archived from the original on March 14, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.