Amazake

Amazake (甘酒, [amazake]) is a traditional sweet, low-alcohol or non-alcoholic Japanese drink made from fermented rice. [1] Amazake dates from the Kofun period, and it is mentioned in the Nihon Shoki.[2] It is part of the family of traditional Japanese foods made using the koji mold Aspergillus oryzae (麹, kōji), which also includes miso, soy sauce, and sake.[3][4]

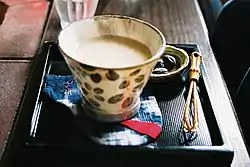

A cup of amazake | |

| Type | Plant milk |

|---|---|

| Course | Drink |

| Place of origin | Japan |

| Region or state | East Asia |

| Associated cuisine | Japanese cuisine |

| Created by | Kofun period in Japan |

| Serving temperature | Warm, room temperature, or cold |

| Main ingredients | Fermented rice |

There are several recipes for amazake that have been used for hundreds of years. By a popular recipe, kōji is added to cooled whole grain rice causing enzymes to break down the carbohydrates into simpler unrefined sugars. As the mixture incubates, sweetness develops naturally.[5][6] By another recipe, sake kasu is mixed with water and sugar is added.[6][7]

Amazake can be used as a dessert, snack, natural sweetening agent, salad dressing or smoothie. One traditional amazake drink, prepared by combining amazake and water, heated to a simmer, and often topped with a pinch of finely grated ginger, was popular with street vendors, and it is still served at inns, teahouses, and at festivals. Many Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples provide or sell it in the New Year.[8] In the 20th century, an instant version became available.

Amazake contains many nutrients, including vitamin B1, B2, B6, folic acid, dietary fiber, oligosaccharide, cysteine, arginine and glutamine.[9] It is often considered a hangover cure in Japan.[10] Outside Japan, it is often sold in Asian grocery stores during the winter months, and, all year round, in natural food stores in the U.S. and Europe, as a beverage and natural sweetener.

Similar beverages include the Chinese jiuniang and Korean gamju. In grape winemaking, must – sweet, thick, unfermented grape juice – is a similar product.

See also

- Akumochizake – Type of Sake

- Brown rice syrup – Sweetener derived from rice

- Choujiu

- Gamju – Korean equivalent of Amazake

- Jiuniang – Chinese equivalent of Amazake

- Must – similar product in winemaking

- Rice milk – Plant milk made from rice

- Rice pudding – Dish made from rice mixed with water or milk

- Small beer – Beer variety, with low alcohol content

- Sikhye

References

- Goldbeck, David; Goldbeck, Nikki (October 1989). "Vegetarian Times" (146): 65.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Studarus, Laura. "Uncovering amazake: Japan's ancient fermented 'superdrink'". www.bbc.com. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- Shurtleff, W.; Aoyagi. A. 1988. Amazake and Amazake Frozen Desserts. Lafayette, California: Soyfoods Center. 69 + [52] pp.

- Shurtleff, William; Aoyagi, Akiko (2021). History of Koji – Grains and/or Soybeans Enrobed in a Mold Culture (300 BCE to 2021): Extensively Annotated Bibliography and Sourcebook (PDF). Lafayette, CA: Soyinfo Center. ISBN 9781948436564.

- "Amazake-Sweet Ambrosia". Mitoku. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- "Amazake". About.com. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 23 January 2010.

- "おうちで簡単 酒粕で甘酒の作り方 作り方・レシピ" [Simple at-home recipe to make sake kasu amazake]. クラシル (in Japanese). Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- "正月に甘酒を飲むのはどうして?神社などで配られる理由" [Why is amazake drank on New Years? Here are the reasons why it is distributed by places such as shrines.]. SELECT PHARMACY(セレクトファーマーシー). 30 December 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2022.

- Belleme, John; Jan Belleme (2007). Japanese Foods That Heal. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 55–58. ISBN 978-0-8048-3594-7. Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- Studarus, Laura (18 March 2020). "Uncovering amazake: Japan's ancient fermented 'superdrink'". BBC Travel. Retrieved 15 April 2023.

External links

- Shurtleff, William; Aoyagi, Akiko (2021). History of Amazake and Rice Milk (1000 BCE to 2021): Extensively Annotated Bibliography and Sourcebook (PDF). Lafayette, CA: Soyinfo Center. ISBN 9781948436557.

Media related to Amazake at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Amazake at Wikimedia Commons