Afro-Vincentians

Afro-Vincentians or Black Vincentians are Vincentians whose ancestry lies within Sub-Saharan Africa (generally West and Central Africa).

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| Approx. 68,125 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Vincentian Creole | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

History

In 1654, when the French tried to dominate the Caribs, they recorded the presence of 3,000 Black people and much fewer pure Caribs ("Yellow"), without making any reference to an individual's state of freedom or slavery. The number was ratified 12 years later in a report by the English Colonel Philip Warner: "In Saint Vicent, a French possession, there are about 3000 black and none of the islands there are that amount of Indians."[2] In 1668, the British broke the treaty signed between France and the Caribs in Basse Terre, and tried to impose, as a first measure of domain, that the Indians [sic] stopped harbouring the black fugitives and delivered them to the British as soon as they were required.[3]

Actually, according to researchers such as the linguist specializing in the Garifuna language Itarala, most of the enslaved people arriving in Saint Vincent came from other Caribbean islands (as, he says, no boat came directly from Africa to the archipelago), and settled in Saint Vincent in order to escape enslavement. So coming to the island were Maroons from plantations on all the surrounding islands, but were diluted in the strong culture of Carib resistance.[4]

Although most of the enslaved people came from Barbados,[5] enslaved people came also from such places as St. Lucia and Grenada. The Barbadians and Saint Lucians arrived on the island pre-1735. After 1775, most of the enslaved people who came from other islands to escape the slavery were Saint Lucians and Grenadians.[6]

After arriving at the island, they were received by the Caribs, who offered protection,[7] enslaved them[8] and, eventually, mixed with them. Addition of the African refugees, the Caribs captured people who were enslaved from neighboring islands (although also they had as slaves white people and his own people), while fighting against the British and French. Many of the captured enslaved people were integrated into their communities (this also occurred in islands such as Dominica), while the others enslaved people were mixed only each other and with the rest of the population of the island.[5]

However, as opposed to Itarala, some authors indicated that many enslaved people of Saint Vincent hailed from human trafficking ports on all the coast of West and Central Africa: Senegambia, Sierra Leone, Windward Coast, Gold Coast, Bight of Benin, Bight of Biafra, Central Africa, and of others areas from Africa. All these places provided thousands of enslaved people to Saint Vincent, specially the Bight of Biafra (from where, apparently, more than 20,000 enslaved people came, some 40% of the enslaved people) and of the Gold Coast (from where came, apparently, more of 11,000 enslaved people, 22% of the enslaved people).[9]

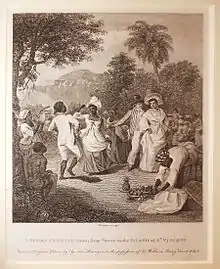

At any rate, to be this well, these enslaved people lived with the enslaved people of the Caribs. So, the "Black Archers", i.e. the population of African origin that had adopted Carib customs and was accepted on an island where the indigenous resistance has not gone off, caused panic among Europeans. A warrior body of Amerindians and free blacks constituted a threat to the plantation slave system and a low blow to the colonial order, unwilling to accept miscegenation that they could not control it. In turn, to ingratiate with the Caribs or because they really felt "belonging to the same single nation",[10] the most of the Black people of St. Vincent in the early eighteenth century wore loincloths, used the bow and arrow, sailed by canoe, used the tables for the infants cranial deformation, touched the snail and painted their bodies with red dye annatto or achiote (Bixa orellana).[11]

On the other hand, perhaps because of its numerical dominance, the Black community pushed the Yellow Caribs towards the leeward side of the island, staying them with the most flat and fertile part (but also more liable to be attacked from the sea) of windward. It also seems true that in 1700 the Yellows asked the intervention of the French against the Black Caribs, however, when visualized they should share their scarce land, preferred to give up the alliance.[12]

Beginning in 1719, French settlers from Martinique gained control of the island and began cultivating coffee, tobacco, indigo, cotton, and sugar on plantations. These plantations were worked by enslaved Africans. In this same year, Blacks and Amerindians repelled a force of 500 French soldiers who, upon landing, burned the villages of the coast and destroyed the plantations.[12]

In 1725, the English tried to settle his time in Saint Vicent. By then, according to Bryan Edwards, Black people were leading the Caribs and his boss spoke "excellent French," in which he recalled to captain Braithwaith that he had rejected to Dutch and English before him, and to the French, their peace cost them many gifts. After which, backed by five hundred men armed with rifles, said he was doing a favor to let him go.[13] Thus, the British returned to their ships then. Since then, during a long time, the Amerindian chiefs and black from Yurumein sold indigo, cotton and snuff produced by women and slaves,[14] and in exchange for which they received arms, ammunition, tools, and wine from the French islands.[15] This was very normal, according to William V. Davidson, after 1750, when the Black Caribs of St. Vincent were quite prosperous and numerous. The black leaders were warriors living with several wives and traveled by canoe to the islands of Martinique, St. Lucia and Grenada to change snuff and cotton they produced, complementing the female agricultural labor with African slave labor, weapons and ammunition.[16]

In 1763 by the Treaty of Paris, France ceded control of Saint Vincent to Britain, who began a program of colonial plantation development that was resisted by the Caribs.

Between 1783 and 1796, there was again conflict between the British and the Black Caribs, who were led by defiant Paramount Chief Joseph Chatoyer. In 1797 British General Sir Ralph Abercromby put an end to the open conflict by crushing an uprising which had been supported by the French radical, Victor Hugues. More than 5,000 Black Caribs were eventually deported to Roatán, an island off the coast of Honduras.

Slavery was abolished in Saint Vincent (as well as in the other British colonies) in 1834, and an apprenticeship period followed which ended in 1838. After its end, labour shortages on the plantations resulted, and this was initially addressed by the immigration of indentured servants (Indian and Portuguese people from Madeira) .

Demography

As of 2013, people of African descent are the majority ethnic group in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, accounting for 66% of the country's population. An additional 19% of the country is multiracial, with many mixed-race Saint Vincentians having partial African descent.[1]

Black Caribs

The Black Caribs are a distinct ethnic group in Saint Vincent, also found in the Caribbean coast of mainland Central America. They are mixture of Caribs, Arawaks and West African people. However, their language is primarily derived from Arawak and Carib, with English and French to a lesser degree. Several theories have been made to explain the arrival of Africans on the island of Saint Vincent and the mixture of many Africans with the Caribs. The best known explanation is that of English governor William Young in 1795.

According to oral history noted by the English governor, the arrival of the African population on the island began with the shipwreck of a ship that hailed from the Bight of Biafra in 1675. The survivors, members of the Mokko people of today's Nigeria (now known as the Ibibio people) reached the small island of Bequia, where the Caribs brought them to Saint Vincent, and, over time, intermarried with them by supplying the African men with wives, since it was taboo in their society for men to go unwed.

However, according to Young, because the enslaved people were "too free of spirit", the Caribs planned to kill all the African male children. When Africans learned of the Caribs' plan, they rebelled and killed as many Caribs as they could, then fled to the mountains, where they settled and lived with other enslaved people who had taken refuge there. However, some researchers, such as the Garifuna specialist linguist Itarala, are more inclined to think, based on documented evidence, that over time enslaved people were actually from other islands (mostly from Barbados, St. Lucia and Grenada), and probably many Africans from the mountains also down from the mountains to have sexual intercourse with women Amerindians or to steal food. Many intermarried with indigenous Africans, thus causing the Black Caribs.[7]

In 1763, the Treaty of Paris awarded Britain rule over Saint Vincent. After a series of Carib Wars, which were encouraged and supported by the French, and the death of their leader Satuye (Chatoyer), they surrendered to the British in 1796. The British considered the Garinagu enemies and deported them to Roatán, an island off the coast of Honduras. In the process, the British separated the more African-looking Caribs from the more Amerindian-looking ones. They decided that the former were enemies who had to be exiled, while the latter were merely "misled" and were allowed to remain. Five thousand Garinagu were exiled, but only about 2,500 of them survived the voyage to Roatán. Because the island was too small and infertile to support their population, the Garifuna petitioned the Spanish authorities to be allowed to settle on the mainland. The Spanish employed them, and they spread along the Caribbean coast of Central America.

See also

References and footnotes

- "The World Factbook -- Saint Vincent and the Grenadines". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2013-05-13.

- Calendar of State Papers (1665–1676), vol. 10, reissue of 1964.

- Calendar of State Papers (1661–1668), vol. 5, reissue of 1964.

- “Escala de intensidad de los africanos en el Nuevo Mundo”, ibidem, p. 136.

- Garifuna reach: Historia de los garífunas. Posted by Itarala. Retrieved 19:30 pm.

- A Brief History of St. Vincent Archived 2013-04-04 at the Wayback Machine

- Marshall, Bernard (December 1973). "The Black Caribs — Native Resistance to British Penetration Into the Windward Side of St. Vincent 1763–1773". Caribbean Quarterly. 19 (4): 4–19. doi:10.1080/00086495.1973.11829167. JSTOR 23050239.

- Charles Gullick, Myths of a Minority, Assen: Van Gorcum, 1985.

- African origins of the slaves from British and former British Antilles

- As stated by Jean-Baptiste Labat in Voyages aux isles de l'Amérique, Paris, 1704, quoted by Ruy Galvao de Andrade Coelho, p. 37.

- John Murungi, "Philosophy as Home in Coming". Democracy, Culture and Development, México: Praxis-UNAM, p. 239.

- Ensayos de Libros: Garifuna - Caribe (Trials of Books).

- Bryan Edwards, vol. I, pages. 415–421.

- "Realizing that there were not enough women to work their gardens, bought slaves." Ruy Galvao de Andrade Coelho, p. 42.

- Rafael Leiva Vivas. Tráfico de Esclavos Negros a Honduras. Tegucigalpa: Guaymuras, 1987, p. 139.

- William V. Davidson. Black Carib (Garifuna) Habitats in Central America. Frontier Adaptations in Lower Central America. Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues. 1976, pp. 85–94.