Environmental issues in Brazil

Environmental issues in Brazil include deforestation, illegal wildlife trade, illegal poaching, air, land degradation, and water pollution caused by mining activities, wetland degradation, pesticide use and severe oil spills, among others.[1] As the home to approximately 13% of all known species, Brazil has one of the most diverse collections of flora and fauna on the planet. Impacts from agriculture and industrialization in the country threaten this biodiversity.[2]

Deforestation

.jpg.webp)

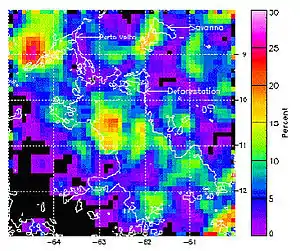

Deforestation in Brazil is a major issue; the country once had the highest rate of deforestation in the world. By far the most deforestation comes from cattle ranchers that clear rainforest (sometimes illegally, sometimes legally), so as to make room for sowing grass and giving their cattle the ability to graze on this location. An important route taken by cattle ranchers and their cattle is the Trans-Amazonian Highway.

Deforestation has been a significant source of pollution, biodiversity loss, and greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, but deforestation has been Brazil's foremost cause of environmental and ecological degradation. Since 1970, over 600,000 square kilometers of Amazonian rainforest have been destroyed and the level of deforestation in the protected zones of Brazil's Amazon rainforest increased by over 127 percent between 2000 and 2010.[3] Recently, further destruction of the Amazon Rainforest has been promoted by an increased global demand for Brazilian wood, meat, and soybeans. Also, as of 2019, some environmental laws have been weakened and there has been a cut in funding and personnel at key government agencies[4] and a firing of the heads of the agency’s state bodies.[5]

Brazil had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.52/10, ranking it 38th globally out of 172 countries.[6]

Hydroelectric dams

Around 150 hydroelectric dams are planned to be constructed in the Amazon basin[7] (of which a large part is situated in Brazil). This could be especially problematic in regards to methane emissions if they would require inundating part of the lowland rainforest.

Endangered species

Brazil is home to over 6% of the world's endangered species.[8] According to a species assessment conducted by the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species, 97 species have been identified in Brazil with vulnerable, lower risk/near threatened, endangered, or critically endangered standing.[9] In 2009, 769 endangered species were identified in Brazil making it home to the eighth largest number of endangered species in the world.[8] Much of this increase in Brazil, as well as the countries it precedes, is caused by rapid deforestation and industrialization. This has been noted by Carlos Minc, Brazil's Environment Minister, who states that as protected areas are populated by humans, preservation areas are lacking the essential protection they need.[10] Changing environmental factors are largely responsible for the increase in the number of endangered species. Taking into account the large effects that deforestation and industrialization have had, it becomes clear that by increasing regulation and policy these detrimental effects can be reversed.

Waste

Brazil's population has a stable growth rate at 0.83% (2012), unlike China or India which are experiencing a rapid urban growth. With a steady growth rate, the challenge for waste management in Brazil is in regard to provision of adequate financing and government funding. While funding is inadequate, lawmakers and municipal authorities are taking steps to improve their individual cities' waste management systems. These individual efforts by city officials are made in response to the lack of an all-encompassing law that manages the entire country's waste materials. Even though there are collection services, they tend to focus in the south and southeast of Brazil. However, Brazil does regulate dangerous waste materials such as oil, tires and pesticides.[11]

In 2014, Brazil hosted the FIFA World Cup. As a result, a great amount of investment entered the country, yet waste management improvements still lack funds. In order to address the lack of federal involvement, the public and private sectors, as well as formal and informal markets, are developing potential solutions to these problems. International organizations as well are teaming up with local city officials such as in the case of the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Since 2008, the UNEP has been working with Brazil to create a sustainable waste management system that promotes environmental preservation and conservation along with the protection of public health. This partnership is between the UNEP and city officials who form the Green and Healthy Environments Project in São Paulo. With community involvement, the project is able to promote policies that establish environmental change. According to a UNEP report, the project has already gathered research on sanitation in Brazil. With the various partnerships and collaborations, certain cities are making strides in efficiently managing their waste, but a more comprehensive and conclusive decision must be made for the entire country to create a more sustainable future.

Collection services

Currently, collection services are more prominent in the south and southeast regions of Brazil. Various methods are used to separate waste materials, such as paper, metal and glass. According to Integrated Municipal Solid Waste Management, solid waste in Brazil is composed of 65% organic matter, 25% paper, 4% metal, 3% glass, and 3% plastic. Within 405 municipalities, 7% of the country's total municipalities, 50% of the separation of these materials is conducted through door-to-door service, 26% through collection points, and 43% through informal street waste pickers.[12] A major victory for waste collection was between 2006 and 2008 when the country's waste collection services expanded to service an additional one million people, bringing the rate of separated waste collection among the country's population to 14%.[13]

Landfills

While waste collection in Brazil is improving slightly, the ultimate of waste commonly takes place in inadequate landfills. While landfills are often viewed as the last option for waste disposal in European nations, preferring waste-to-energy systems instead, Brazil favors landfills and believes they are efficient modes of disposal. The preference for landfills has hindered the creation of alternative methods of waste disposal. Often, this hesitation is in response to the initial costs of adopting new solutions. For example, incinerators are expensive to purchase, operate and maintain, eliminating them as an option for most cities in Brazil. According to the Integrated Municipal Solid Waste Management Manual, landfill usage will begin to fall due to new regulation and laws. As the risks and environmental hazards of open air landfills are understood by municipality administrators in Brazil, more dumps are being closed in favor of sanitary landfills. However, these policy changes will only happen with appropriate financing.

Waste-to-energy

Waste-to-energy is one way to dispose of all combustible waste in which recycling alone is not economically viable. As income levels rise in the southern region of Brazil, citizens are urging officials to improve waste management systems. However, the results are limited as no commercial facilities are currently being constructed. Even though citizens and officials are beginning to understand the harm of landfills and the importance of waste management, most do not understand waste-to-energy systems. On the other hand, waste-to-energy industry leaders do not understand the current waste condition in Brazil. In order to provide specific solutions to problems in Brazil, the Waste to Energy Research Technology Counsel in Brazil is developing a hybrid municipal solid waste (MSW)/natural gas cycle. This system burns a small amount of natural gas that is 45% efficient and 80% of the energy that is produced by MSW is 34% efficient. Their patented system takes a small gas turbine and mixes it with preheated air. Another benefit of using low amounts of natural gas is the possibility of replacing it with landfill gas, ethanol, or renewable fuels. Another benefit is that this system does not change current incinerator technology, which allows it to use components that already exist in other waste-to-energy plants. Private sector involvement in the waste-to-energy industry includes companies such as Siemens, CNIM, Keppel-Seghers, Hitachi Zosen Inova, Sener, Pöyry, Fisia-Babcock, Malcolm Pirnie and others who are already established in Brazil and developing waste-to-energy projects. Some cities currently considering such projects are Belo Horizonte, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, São José dos Campos, São Bernardo do Campo and others. Clean development mechanism projects are also beginning to develop at some Brazilian landfills. These projects are established to collect gases produced on-site and convert them into energy. For example, at a landfill in Nova Iguaçu (Rio de Janeiro area), methane is being collected and converted into electricity. This process is expected to eliminate 2.5 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions by 2012.[14]

Recycling

According to data from the Brazilian Association of Public Cleaning and Special Waste Companies including sewage, Brazil is a leader in aluminum can recycling without government intervention with ten cans being recycled every year. In 2007, more than 96% of cans available in the market were recycled. This leadership comes from informal waste scavengers that make their living by collecting aluminum cans. However, recycling in general in Brazil is low. Brazil produces 240 thousand tons of waste every day. Out of this amount, only 2% is recycled with the remainder dumped in landfills. In 1992, private companies in Brazil established the Brazilian Business Commitment for Recycling (CEMPRE), a nonprofit organization that promotes recycling and waste elimination. The organization issues publications, conducts technical research, holds seminars and maintains databases. Nevertheless, only 62% of the population has access to the garbage collection. Even within these collection systems, the collection of recyclable material is not common. The success of informal waste pickers provided evidence to lawmakers and citizens that solutions that are low tech, low cost, and labor-intensive can provide sustainable solutions to waste management while also providing social and economic benefits.[15] Recycling is very important in are surrounding because many of the people throw the garbage in the rivers.

Production of first-generation biofuels

Brazil is the second-largest producer of ethanol in the world.[16] Ethanol production in Brazil uses sugarcane as feedstock and relies on first-generation biofuel technologies based on the use of the sucrose content of sugarcane. First-generation biofuels

Pollution

Air pollution

Due to its unique position as the only area of the world which extensively utilizes ethanol, air quality issues in Brazil relate more to ethanol-derived emissions. With about 40% of fuel used in Brazilian vehicles sourced from ethanol, air pollution in Brazil differs from that of other nations where predominately petroleum or natural gas-based fuels are used. Atmospheric concentrations of acetaldehyde, ethanol and possibly nitrogen oxides are greater in Brazil than most other areas of the world due to their emissions being higher in vehicles using ethanol fuels. The larger urban areas of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Brasilia suffer from substantial ozone issues because both acetaldehyde and nitrogen oxides are significant contributors to photochemical air pollution and ozone formation. On the other hand, by the mid-1990s, lead levels in the air had decreased by approximately 70% after the widespread introduction of unleaded fuels in Brazil in 1975.[17]

Numbers of automobiles and levels of industrialization in Brazilian cities highly influence levels of air pollution in urban areas which have an important impact on health for large population groups in major Brazilian urban areas. Based on annual air pollution data gathered in the cities of Belo Horizonte, Fortaleza, Porto Alegre, Rio de Janeiro, São Paulo, and Vitória between the years of 1998 and 2005, 5% of total annual deaths in the age groups of children age five and younger and adults age 65 and older were attributed to air pollution levels in these cities.[18] Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo were ranked the 12th and 17th most polluted cities in an evaluation based on World Bank and United Nations data of emissions and air quality in 18 mega-cities. The multi-pollutant index used to perform the evaluation did not include any of the pollutants specific to the air quality impacts of ethanol fuel use.[17]

Industrial pollution

The city of Cubatão, designated by the Brazilian government as an industrial zone due in part to its proximity to the Port of Santos, became known as the "Valley of Death" and "the most polluted place on Earth". The area has historically housed numerous industrial facilities including an oil refinery from Petrobras and a steel mill from COSIPA. Operation of such facilities was done so "without any environmental control whatsoever" prompting tragic events throughout the 1970s and 1980s including mudslides and birth defects potentially attributable to heavy pollution in the region. Since that time, efforts have been made to improve environmental conditions in the area including, since 1993, COSIPA's $200 million investment in environmental controls. In 2000, Cubatão's center registered 48 micrograms of particles per cubic meter of air, down from 1984 measurements registering 100 micrograms of particles per cubic meter.[19]

Likely due to trade liberalization, Brazil has a high concentration of pollution-intensive export industries. Studies point to this as evidence of Brazil being a pollution haven. The highest of levels of pollution intensity are found in export-related industries such as metallurgy, paper and cellulose, and footwear.[20]

Water pollution

Brazil’s major and medium size metropolitan areas face increasing problems of water pollution. Coastal cities such as Rio de Janeiro and Recife suffer effects of upstream residential and industrial sewage contaminating feeder rivers, lakes, and the ocean. In 2000, only 35% of collected wastewater received any treatment.[21]

For example, the Tietê River, which runs through the São Paulo metropolitan area (17 million inhabitants), has returned to its 1990 pollution levels. Despite the support from the IDB, the World Bank and Caixa Econômica Federal in a US$400 million cleanup effort, the level of dissolved oxygen has returned to the critical level of 1990 at 9 mg per liter due to increased levels of unregulated sewerage, phosphorus, and ammonia nitrogen discharged into the river.[22] As of 2007, the state water company Sabesp projects that a minimum of R$3 billion (US$1.7bn) would be necessary to clean up the river.[23]

The South and Southeast regions of Brazil experience water scarcity due to overexploitation and misuse of surface water resources, mostly attributable to heavy pollution from sewage, leaking landfills, and industrial waste.[24][25]

According to an investigation by Unearthed, more than 1,200 pesticides and weedkillers, including 193 containing chemicals banned in the EU, have been registered in Brazil between 2016 and 2019.[26][27]

Water pollution is also derived from ethanol production. Due to the size of the industry, its agroindustrial activity in growing, harvesting, and processing sugarcane generates water pollution from the application of fertilizers and agrochemicals, soil erosion, cane washing, fermentation, distillation, the energy producing units installed in mills and by other minor sources of waste water.[25]

The two greatest sources of water pollution from ethanol production come from mills in the form of waste water from washing sugarcane stems prior to passing through mills, and vinasse, produced in distillation. These sources increase the biochemical oxygen demand in the waters where they are discharged which leads to the depletion of dissolved oxygen in the water and often causes anoxia. Legislation has banned the direct discharge of vinasse onto surface waters, leading it to be mixed with waste water from the sugarcane washing process to be reused as organic fertilizer on sugarcane fields. Despite this ban, some small sugarcane mills still discharge vinasse into streams and rivers due to a lack of transportation and application resources. Furthermore, vinasse is sometimes mishandled in storage and transport in mills.[28]

Guanabara Bay has had three major oil spills as well as other forms of pollution.

The Tietê River has for over twenty years been afflicted with heavy pollution from sewage, primarily from São Paulo, and manufacturing. In 1992, the Tietê Project was initiated in an effort to clean up the river. São Paulo today processes 55% of its sewage and is expected to process 85% by 2018.[29]

Mercury pollution from gold mining in Brazil has led to contamination of fish in the state of Amapá.[30]

Climate change

Climate change in Brazil is mainly the climate of Brazil getting hotter and drier. The greenhouse effect of excess carbon dioxide and methane emissions makes the Amazon rainforest hotter and drier, resulting in more wildfires in Brazil. Parts of the rainforest risk becoming savanna.

Brazil's greenhouse gas emissions per person are higher than the global average, and Brazil is among countries which emit a large amount of greenhouse gas. Greenhouse gas emissions by Brazil are almost 3% of the annual world total.[31] Firstly due to cutting down trees in the Amazon rainforest, which emitted more carbon dioxide in the 2010s than it absorbed.[32] And secondly from large cattle farms, where cows belch methane. In the Paris Agreement Brazil promised to reduce its emissions, but the incumbent Bolsonaro government has been criticized for doing too little to limit climate change or adapt to climate change.[33]Solutions and policies

Brazil has a generally advanced and comprehensive legislation on environmental protection and sustainability. Laws regarding forests, water, and wildlife have been in effect since the 1930s.[34] Until the mid-1990s, environmental legislation addressed isolated environmental issues; however, the legal framework has been improved through new policy-making that targets environmental issues within the context of an integrated environmental policy.[35] The Brazilian government strives toward the preservation and sustainable development of Brazilian biomes. Consequently, the Brazilian government developed strategies to impose specific policies for each biome and organize opportunities for social participation, institutional reform of the forestry sector, and expansion of the biodiversity concept. For example, the program Legal Earth, developed by the Ministries of Agrarian Development and Environment, has the responsibility to regulate the use of public lands occupied in the Amazon region. This program was successful in restricting the marketing of meat produced on illegally deforested areas and the proper identification of permitted areas for growing sugarcane for the production of ethanol.[36]

Brazil recognized that it was part of the solution to the problem of climate change. In 2010, Brazil took the necessary steps to advance its climate change commitments made at the COP-15 in Copenhagen. For example, the policy to combat deforestation in the Amazon in had produced positive results, as demonstrated by announcements of increasingly lower deforestation rates.[37]

Between 2000 and 2010, the deforestation took huge proportions. Then, in 2011, data from the Brazilian Ministry of Environment showed a decrease in deforestation rates in the Amazon Rainforest. This is in part due to an increased awareness of the damaging effects of prolific logging practices and a shift toward sustainable forestry in Brazil.

Although forestry companies—many of which are based outside of Brazil—are interested in increasing their longevity, the Brazilian government has been actively promoting more sustainable forestry policies for years. Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (INPE) has helped reduce deforestation levels over the course of 2011 through its Real Time Deforestation Detection System (DETER). Besides DETER, INPE also has the Amazon Deforestation Satellite Monitoring Project (PRODES).[38] Furthermore, Brazil has negotiated to use satellites from India to improve the monitoring of deforestation in the Amazon rain forest. In addition, the Government took measures to more effectively enforce its deforestation reduction policy through shutting down illegal sawmills and seizing illegal timber and vehicles. Brazilian officials and environmental advocates alike were confident that these measures would enhance the Brazilian government's ability to combat deforestation, biodiversity loss, and pollution.

Data from 2010 showed that Brazil has reduced deforestation rates in the Amazon by more than 70%, the lowest deforestation rate in over 20 years. At this rate, Brazil's goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 38.9% was to be reached by 2016 rather than 2020.[39] Between 2010 and 2018, Amazon deforestation rates have indeed been low, but data suggests that (in the Amazon region), since 2019, the deforestation rate is again rising considerably.[40]

Despite all those efforts, however, the problem with deforestation and illegal logging has remained a very serious issue in the country.

Governmental organizations

The Ministry of Environment is responsible for Brazil's national environmental policy. The ministry's many departments deal with climate change and environmental quality, biodiversity and forests, water resources, sustainable urban and rural development, and environmental citizenship. Other authorities are also responsible for the implementation of environmental policies, including the National Council on the Environment, the National Council of the Amazon, the National Council of Water Resources, the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBIO), Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), Board of Management of Public Forests, and others. The collaborative work of these institutions makes it possible to ensure sustainable growth within the means of the environment.[36]

Non-governmental organizations

The development of institutions at the governmental level was stimulated and accompanied by the diffusion and increasing importance of NGOs dedicated to environmental causes and sustainable development. Numerous NGOs throughout Brazil produce documents containing both useful information and criticisms.[34]

| Name | Foundation Year | Mission[41] |

|---|---|---|

| SOS Mata Atlântica | 1986 | Defend the Atlantic Forest areas, protect the communities that inhabit the region, and preserve their natural, historical, and cultural heritage. |

| Socio Environmental Institute | 1994 | Defend rights related to the environment, cultural heritage, and human rights. |

| Greenpeace | Defend the environment by raising awareness about environmental issues and influence people to change their habits. | |

| WWF-Brasil | 1996 | Instruct Brazilian society on how to use natural resources in a rational manner. |

| Conservation International (CI) | 1987 | Protect biodiversity and instruct society on how to live in harmony with nature. |

| Akatu Institute | Guide Brazil's consumption habits toward a sustainable model. | |

| Ecoar Institute | After Rio-92 | Provide environmental education as an effort to rescue degraded areas and implement local sustainable development programs and projects. |

| Ecoa | 1989 | Create a space for negotiations and decisions about environmental protection and sustainability. |

| Recicloteca | Diffuse information on environmental issues, especially for the reduction, reutilization, and recycling of waste. | |

| Friends of the Earth-Brazilian Amazon | 1989 | Develop projects and activities that promote sustainable development in the Amazonian region. |

| National Network to Fight the Trafficking of Wild Animals (Renctas) | 1999 | Combat the trafficking of wild animals and contribute to biodiversity protection. |

| Atlantic Forest NGO Network | Provide information about NGOs that work toward the protection of the Atlantic Forest. | |

| Brazilian Forum of NGOs and Social Movements for the Environment and Development (FBOMS) | 1990 | Facilitate the participation of the public in the United Nations Conference on Environment (UNCED). |

| Brazilian Foundation for Sustainable Development (FBDS) | 1992 | Implement the conventions and treaties approved at Rio-92. |

International agreements

As part of Brazil's environmental initiatives, it is party to the following international agreements: Antarctic-Environmental Protocol, Antarctic-Marine Living Resources, Antarctic Seals, Antarctic Treaty, Biodiversity, Climate Change, Kyoto Protocol, Desertification, Endangered Species, Environmental Modification, Hazardous Wastes, Law of the Sea, Marine Dumping, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Tropical Timber 83, Tropical Timber 94, Wetlands, Whaling,[1] and the Paris Agreement.

Map of Conflicts Related to Environmental Injustice and Health in Brazil

The "Map of Conflicts Related to Environmental Injustice and Health in Brazil" is an online map of conflicts relating to environmental injustice and health in Brazil. The map is maintained by the National School of Public Health of Brazil, the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation, and Núcleo Ecologías, Epistemiologias e Promoção Emancipatória da Saude (NEEPES). Since 2008, the project has mapped and described major cases of environmental conflicts in all Brazilian regions. The map has been online since 2010.[42] As of June 2022, the map listed at least 600 conflicts.

Governmental Role in Environmental issues

Spearheading the current-day exploitation of the Amazon Rainforest is the administration of President Jair Bolsonaro. Originally running on a platform that included supporting extractivist interests such as enforcing environmental regulations, reforestation, and added protections, Bolsonaro has done quite the opposite.[43] The President encourages the ideology that the Brazilian economy should not be restricted by environmental concerns. His administration has taken all possible steps to increase accessibility to logging, agriculture, and poaching at the great expense of the environment.[43] They have shown a consistent pattern of undermining environmental NGOs, and they periodically announce environmental protection enforcements that typically are not seen through with just to keep international pressures at bay. as of July 2019, about 7 months into his term, the Amazon had lost 1,330 square miles of forest coverage, a 39 percent increase from the period before.[44] Statistics that have continued to increase since. Bolsonaro has also cut the Brazilian Environmental Agency's budget by 24 percent which has led to a 20 percent decrease in their activity.[44] All of this is propelled by the thought that the Amazon Rainforest is theirs to be used for the benefit of the country, prioritizing financial profits over the well-being of the environment.[43]

Human Rights Watch sent in a team to Brazil who spent about a year and a half collecting information and interviewed about 170 people, half government employees and half community members.[44] They were investigating a series of forest fires that the Brazilian Government, namely the Environment Minister Joaquim Leite had claimed were due to dry weather. However, satellite imaging showed these fires occurring where rainforest had been cleared for deforestation, and where as a rainforest it would not make sense to have such fires.[44] What they found was that these fires were driven by criminal organizations using violence and intimidation upon forest defenders so that they could benefit from the deforestation. They linked 28 killings of people who were trying to stop these fires back to the criminal networks.[44] Bolsonaro has cleared a path for criminals such as these to operate with few consequences, making illegal deforestation almost impossible to prosecute.[43]

One of the large reasons for the recent increase in deforestation in the Amazon Rainforest has been the Ruralista movement, also known as the Landless Workers Movement. Their message is that the large swaths of the Amazon that serve no purpose will be widely privatized, providing a flow of money for the Brazilian economy.[45] This movement consists mainly of very wealthy, conservative people who have used their money to gain political power. With this power, they have acquired a significant membershio in Brazil's National Congress. Their first notable action was rewriting the country's forest code in 2012, where they essentially managed to grant amnesty for illegal deforestation of the Amazon.[45] These Ruralistas were also heavy supporters of Bolsonaro's campaign, and he has repaid them by selecting multiple Ruralistas to be ministers, such as the ministers of agriculture and the environment. Therefore, while Bolsonaro remains in power, the Ruralista agenda of using the Amazon's resources at any environmental cost will continue.[45]

While Bolsonaro's administration has certainly damaged the Brazilian environment considerably, he is restricted in several ways. For example, agribusiness is a very large and important part of the Brazilian economy, and therefore it is very important in Congress. Influential sectors of agribusiness are committed to environmental protection, and this balances out some of the ruralista violations.[44] Another is that international pressure, such as the environmental summits that Bolsonaro attends have considerable influence. President Bolsonaro, especially with an election coming up, favors having some credibility with the international environmental protection community. The Public Prosecutor's Office and the Brazilian Judiciary have both been instrumental in limiting the amount of damage that the President is able to inflict upon the environment.[44]

Under Bolsonaro, Brazil has been environmentally a very different country than they have been historically. For example, in 2009 Brazil committed to decreasing deforestation to 4,000 square per year, but deforestation has been increasing every year since 2012.[44] In addition, they made a commitment under the Paris Agreement to eliminate all deforestation by 2030, which they could still accomplish under different leadership.[44] Housing such a massive portion of the Amazon Rainforest, an important carbon sink, puts Brazil in a position of major power with whether the country chooses to help or hurt the Earth's worsening climate change issues.[44] If Boslonaro is re-elected, the country will continue to increase deforestation, but if another candidate such as Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, chances are good that the country re-aligns with their historical identity as a champion of environmental rights.

See also

References

- "The World Factbook: Brazil". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- "Biodiversity – Portal Brasil". Brasil.gov.br. 2010-01-18. Archived from the original on 2012-07-31. Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- Tavener, Ben (2011-10-11). "Brazil Deforestation: Winning Battle, Losing War". The Rio Times. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- "Amazon Deforestation in Brazil Rose Sharply on Bolsonaro's Watch (Published 2019)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2023-06-04.

- Brazil guts environmental agencies, clears way for unchecked deforestation

- Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity - Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507. S2CID 228082162.

- How a Dam Building Boom Is Transforming the Brazilian Amazon

- Choppin, Simon (2009-11-03). "Red list 2009: Endangered species for every country in the world". theguardian.com. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- Platt, John (April 27, 2009). "Brazil's endangered species list triples in size". mnn.com. Mother Nature Network. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- "Batteries in Brazil". IHS. Archived from the original on 2013-11-12. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- Guerreiro Ribeiro, Sergio (June 2011). "WtE: the Redeemer of Brazil's waste legacy?". Waste Management World. 12 (3). Archived from the original on 2012-01-24. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- "CEMPRE – Compromisso Empresarial para Reciclagem" (in Portuguese). CEMPRE. Archived from the original on 2012-04-26. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- "Updated Project Information Document: BRAZIL – Nova Gerar Landfill Rio de Janeiro" (PDF). The World Bank. 2004-03-17. Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- "Waste Pickers & Solid Waste Management". WIEGO. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- "World Fuel Ethanol Production". Renewable Fuels Association. Archived from the original on 2012-02-11. Retrieved 2012-03-07.

- Anderson, Larry G (2009). "Ethanol fuel use in Brazil: air quality impacts". Energy & Environmental Science. 2 (10): 1015–1037. doi:10.1039/B906057J.

- Marcilio, Izabel; Gouveia, Nelson (2007). "Quantifying the impact of air pollution on the urban population of Brazil" (PDF). Cad. Saúde Pública. Rio de Janeiro. 23 (Sup 4): S529–S536. doi:10.1590/S0102-311X2007001600013. PMID 18038034.

- "'Valley of Death' breathes again, barely". The Indian Express. Reuters. 2000-07-12. Archived from the original on 2006-03-06.

- Working Group on Development and Environment in the Americas (June 2004). "Trade and liberalization, environment and development" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics (IBGE):National Survey of Basic Sanitation (PNSB) 2000 pt:Pesquisa Nacional de Saneamento Básico

- (in Portuguese) "Piora nivel de poluicao do Tiete" Estado de São Paulo Newspaper. 16 May 2007.

- (in Portuguese) "Limpar of Tiete exige mais de R$3 bi." Estado de São Paulo. 17 May 2007.

- "Water Statistics in Brazil: a preliminary [view / approach]" (PDF). Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- Moreira, Jose Roberto. "Water Use and Impacts Due Ethanol Production in Brazil" (PDF).

- Brazil pesticide approvals soar

- "Hundreds of new pesticides approved in Brazil under Bolsonaro". The Guardian. 2019-06-12. Archived from the original on 2023-04-10.

- Martinelli, Luis; Filoso, Solange (2008). "Expansion of sugarcane ethanol production in Brazil: environmental and social challenges" (PDF). Ecological Applications. 18 (4): 885–898. doi:10.1890/07-1813.1. PMID 18536250. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2019-01-06.

- "Pollution in Brazil: The silvery Tietê". The Economist. 2011-10-22. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- "Mercury from gold mining contaminates Amazon communities' staple fish". Mongabay Environmental News. 2020-09-03. Retrieved 2020-10-03.

- "Report: China emissions exceed all developed nations combined". BBC News. 2021-05-07. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- "Brazilian Amazon released more carbon than it absorbed over past 10 years". the Guardian. 2021-04-30. Archived from the original on 2021-04-30. Retrieved 2021-05-01.

- Research, Behavioural and Social Sciences at Nature (2020-12-30). "The threat of political bargaining to climate mitigation in Brazil". Behavioural and Social Sciences at Nature Research. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- Hudson, Rex A., ed. (1997). "The Society and Its Environment: The Environment". Brazil: A Country Study. Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- sarkar, pijush. "The Amazon has been burning for 16 days, the lung of the world, which is home to date, at least 40,000 plant species, 427 mammals (e.g. jaguar, anteater and giant otter), 1,300 birds (e.g. harpy eagle, toucan, and hoatzin), 378 reptiles (e.g. boa), more than 400 amphibians (e.g. dart poison frog) and around 3,000 freshwater fishes including the piranha have been found in the Amazon. Out of the plants, there are 16000 species of trees". environmental studies. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- "Government Actions – Portal Brasil". Brasil.gov.br. 2010-02-19. Retrieved 2011-12-06.

- "Climate change – Portal Brasil". Brasil.gov.br. Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- DETER and PRODES

- "Brazil". State.gov. 2011-11-30. Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- Deforestation rates in the Amazon shooting up in 2019

- "Environmental Non-Governmental Organizations – Portal Brasil". Brasil.gov.br. Archived from the original on 2012-07-22. Retrieved 2011-12-11.

- da Rocha, Diogo Ferreira; Porto, Marcelo Firpo; Pacheco, Tania; Leroy, Jean Pierre (2017-10-17). "The map of conflicts related to environmental injustice and health in Brazil". Sustainability Science. 13 (3): 709–719. doi:10.1007/s11625-017-0494-5. ISSN 1862-4065. S2CID 158898263.

- Menezes, Roberto Goulart; Barbosa Jr., Ricardo (2021). "Environmental governance under Bolsonaro: dismantling institutions, curtailing participation, delegitimising opposition". Zeitschrift für Vergleichende Politikwissenschaft. 15 (2): 229–247. doi:10.1007/s12286-021-00491-8. ISSN 1865-2646. PMC 8358914.

- Trebat, Thomas; Nora, Laura; Caldwell, Inga. "Threats to the Brazilian Environment and Environmental Policy" (PDF). Columbia Global Centers.

- "Brazil, once a champion of environmentalism, grapples with new role as climate antagonist". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-09-25.

.svg.png.webp)