Geography of Ghana

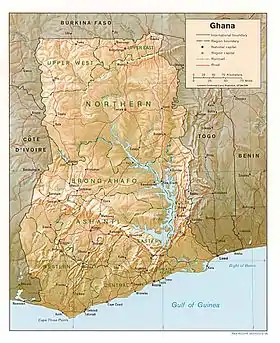

Ghana is a West African country in Africa, along the Gulf of Guinea.

| Ghana | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Continent | Africa |

| Geographic coordinates | 8°00′N 2°00′W |

| Area | Ranked 82nd |

| - Total | 238,533 square kilometres (92,098 sq mi) |

| - % water | 3.5% (8,520 square kilometres (3,290 sq mi)) |

| Coastline | 539 km |

| Highest point | Mount Afadja, 885 m |

| Lowest point | Atlantic Ocean, 0 m |

| Longest river | Volta |

| Largest inland body of water | Lake Volta |

| Land Use | |

| - Arable land | 20.66 % |

| - Permanent crops | 11.87 % |

| - Other | 67.48% (2012) |

| Irrigated land | 309 square kilometres (119 sq mi) (2003) |

| Climate | Tropical |

| Natural resources | industrial minerals, gold, timber, industrial diamonds, bauxite, manganese, fish, rubber, hydropower, petroleum, natural gas, silver, salt, limestone |

| Environmental issues | drought, deforestation, overgrazing, soil erosion, poaching, habitat destruction, water pollution |

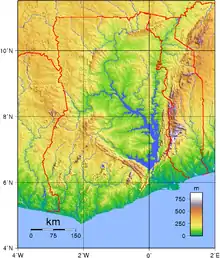

Ghana encompasses plains, low hills, rivers, Lake Volta, the world's largest artificial lake, Dodi Island and Bobowasi Island on the south Atlantic Ocean coast of Ghana. Ghana can be divided into four different geographical ecoregions. The coastline is mostly a low, sandy shore backed by plains and scrub and intersected by several rivers and streams. The northern part of Ghana features high plains. South-west and south-central Ghana is made up of a forested plateau region consisting of the Ashanti uplands and the Kwahu Plateau. The hilly Akwapim-Togo ranges are found along Ghana's eastern international border.

The Volta Basin takes up most of south-central Ghana and Ghana's highest point is Mount Afadja which is 885 m (2,904 ft) and is found in the Akwapim-Togo ranges. The climate is tropical and the eastern coastal belt is warm and comparatively dry, the south-west corner of Ghana is hot and humid, and the north of Ghana is warm and wet. Lake Volta, the world's largest artificial lake, extends through small portions of south-eastern Ghana and many tributary rivers such as the Oti and Afram rivers flow into it.

The northernmost part of Ghana is Pulmakong and the southernmost part of Ghana is Cape three points near Axim. Ghana lies between latitudes 4° and 12°N. South Ghana contains evergreen and semi-deciduous forests consisting of trees such as mahogany, odum, ebony and it also contains much of Ghana's oil palms and mangroves with shea trees, baobabs and acacias found in the northern part of Ghana.

Location and Density

Ghana, which lies in the centre of the Gulf of Guinea coast, 2,420 km of land borders with three countries: Burkina Faso (602 km) to the north, Ivory Coast (720 km) to the west, and Togo (1,098 km) to the east. To the south are the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean.

Its southernmost coast at Cape Three Points is 4° 30' north of the equator.[1] From here, the country extends inland for some 670 kilometres (420 mi) to about 11° north.[1] The distance across the widest part, between longitude 1° 12' east and longitude 3° 15' west, measures about 560 kilometres (350 mi).[1]

The Greenwich Meridian, which passes through London, also traverses the eastern part of Ghana at Tema.[1]

With a total area of 238,533 square kilometres (92,098 sq mi),[2]

Terrain of Ghana

The terrain consists of desert mountains with the Kwahu Plateau in the south-central area. Half of Ghana lies less than 152 meters (499 ft) above sea level, and the highest point is 883 meters (2,897 ft). The 537 kilometers (334 mi) coastline is mostly a low, sandy shore backed by plains and scrub and intersected by several rivers and streams, most of which are navigable only by canoe.

A tropical rain forest belt, broken by heavily forested hills and many streams and rivers, extends northward from the shore, near the Ivory Coast frontier. This area, known as the "Ashanti," produces most of Ghana's cocoa, minerals, and timber. North of this belt, the elevation varies from 91 to 396 meters (299 to 1,299 ft) above sea level and is covered by low bushes, park-like savanna, and grassy plains.

Irrigated land:

309 square kilometers (119 sq mi) (2003)

Total renewable water resources:

53.2 cubic kilometers (13 cu mi) (2011)

Geographical regions

Ghana is characterized in general by low physical relief. The Precambrian rock system that underlies most of the nation has been worn down by erosion almost to a plain.[1] The highest elevation in Ghana, Mount Afadja in the Akwapim-Togo Ranges, rises 880 metres (2,890 ft) above sea level.[1]

There are four distinct geographical regions.[1] Low plains stretch across the southern part of Ghana. To their north lie three regions—the Ashanti Uplands, the Akwapim-Togo Ranges, and the Volta Basin.[1] The fourth region, the high plains, occupies the northern and northwestern sector of Ghana.[1] Like most West African countries, Ghana has no natural harbours.[1] Because strong surf pounds the shoreline, two artificial harbours were built at Takoradi and Tema (the latter completed in 1961) to accommodate Ghana's shipping needs.[1]

Low plains

The low plains comprise the four subregions of the coastal savanna, the Volta Delta, the Accra Plains, and the Akan lowlands or peneplains.[1] A narrow strip of grassy and scrubby coast runs from a point near Takoradi in the west to the Togo border in the east.[1] This coastal savanna, only about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) in width at its western end, stretches eastward through the Accra Plains, where it widens to more than 80 kilometres (50 mi), and terminates at the southeastern corner of the country at the lower end of the Akwapim-Togo Ranges.[1]

Almost flat and featureless, the Accra Plains descend gradually to the gulf from a height of about 150 metres (490 ft).[1] The topography east of the city of Accra is marked by a succession of ridges and spoonshaped valleys.[1] The hills and slopes in this area are the favoured lands for cultivation.[1] Shifting cultivation is the usual agricultural practice because of the swampy nature of the very lowlying areas during the rainy seasons and the periodic blocking of the rivers at the coast by sandbars that form lagoons.[1] A plan to irrigate the Accra Plains was announced in 1984.[1] Should this plan come to reality, much of the area could be opened to large-scale cultivation.[1]

To the west of Accra, the low plains contain wider valleys and rounded low hills, with occasional rocky headlands.[1] In general, however, the land is flat and covered with grass and scrub.[1] Dense groves of coconut palms front the coastline.[1] Several commercial centres, including Winneba, Saltpond, and Cape Coast are located here. Winneba has a small livestock industry and palm tree cultivation is expanding in the area away from the coast, with the predominant occupation of the coastal inhabitants being fishing via dug-out canoe.[1]

The Volta Delta, which forms a distinct subregion of the low plains, extends into the Gulf of Guinea in the extreme southeast.[1] The delta's rock formation—consisting of thick layers of sandstone, some limestone, and silt deposits—is flat, featureless, and relatively young.[1] As the delta grew outward over the centuries, sandbars developed across the mouths of the Volta and smaller rivers that empty into the gulf in the same area, forming numerous lagoons, some quite large, making road construction difficult.[1]

To avoid the lowest-lying areas the road between Accra and Keta makes a detour inland just before reaching Ada, and approaches Keta from the east along the narrow spit on which the town stands.[1] Road links with Keta continue to be a problem.[1] By 1989 it was estimated that more than 3,000 houses in the town had been swallowed by flooding from the lagoon.[1] About 1,500 other houses were destroyed by erosion caused by the powerful waves of the sea.[1]

This flat, silt-composed delta region with its abundance of water supports shallot, corn, and cassava cultivation in the region.[1] The sandy soil of the delta gave rise to the copra industry.[1] Salt-making, from the plentiful supply in the dried beds of the lagoons, provides additional employment.[1] The main occupation of the delta people is fishing, an industry that supplies dried and salted fish to other parts of the country.[1]

The largest part of the low plains is the Akan Lowlands.[1] Some experts prefer to classify this region as a subdivision of the Ashanti Uplands because of the many characteristics they share.[1] Unlike the uplands, the height of the Akan Lowlands is generally between sea level and 150 metres (490 ft).[1] Some ranges and hills rise to about 300 metres (980 ft), but few exceed 600 metres (2,000 ft).[1] The lowlands that lie to the south of the Ashanti Uplands receive the many rivers that make their way to the sea.[1]

The Akan Lowlands contain the basins of the Densu River, the Pra River, the Ankobra River, and the Tano River, all of which play important roles in the economy of Ghana.[1] The Densu River Basin, location of the important urban centres of Koforidua and Nsawam in the eastern lowlands, has an undulating topography.[1] Many of the hills here have craggy summits, which give a striking appearance to the landscape.[1] The upper section of the Pra River Basin, to the west of the Densu, is relatively flat.[1] The topography of its lower reaches resembles that of the Densu Basin and is a rich cocoa and food-producing region.[1] The valley of the Birim River, one of the main tributaries of the Pra, is Ghana's most important diamond-producing area.[1]

The Ankobra River Basin and the middle and lower basins of the Tano River to the west of the lowlands form the largest subdivision of the Akan Lowlands.[1] Here annual rainfall between 1,500 and 2,150 millimetres (59 and 85 in) helps assure a dense forest cover.[1] In addition to timber, the area is rich in minerals.[1] The Tarkwa goldfield, the diamond operations of the Bonsa Valley, and high-grade manganese deposits are all found in this area.[1] The middle and lower Tano basins have been intensely explored for oil and natural gas since the mid-1980s.[1] The lower basins of the Pra, Birim, Densu, and Ankobra rivers are also sites for palm tree cultivation.[1]

Comprising the Southern Ashanti Uplands and the Kwahu Plateau, the Ashanti Uplands lie just north of the Akan Lowlands and stretch from the Ivory Coast border in the west to the elevated edge of the Volta Basin in the east.[1] Stretching in a northwest-to-southeast direction, the Kwahu Plateau extends 193 kilometres (120 mi) between Koforidua in the east and Wenchi in the northwest.[1] The average elevation of the plateau is about 450 metres (1,480 ft), rising to a maximum of 762 metres (2,500 ft).[1] The relatively cool temperatures of the plateau were attractive to Europeans, particularly missionaries, who founded many well-known schools and colleges in this region.[1]

The plateau forms one of the important physical divides in Ghana.[1] From its northeastern slopes, the Afram and Pru Rivers flow into the Volta River, while from the opposite side, the Pra, Birim, Ofin, Tano, and other rivers flow south toward the sea.[1] The plateau also marks the northernmost limit of the forest zone.[1] Although large areas of the forest cover have been destroyed through farming, enough deciduous forest remains to shade the head waters of the rivers that flow from the plateau.[1]

The Southern Ashanti Uplands, extending from the foot of the Kwahu Plateau in the north to the lowlands in the south, slope gently from an elevation of about 300 metres (980 ft) in the north to about 150 metres (490 ft) in the south.[1] The region contains several hills and ranges as well as several towns of historical and economic importance, including Kumasi, Ghana's second largest city and former capital of the Asante.[1] Obuasi and Konongo, two of the country's gold-mining centres, are also located here.[1] The region is Ghana's chief producer of cocoa, and its tropical forests continue to be a vital source of timber for the lumber industry.[1]

Volta Basin

Taking the central part of Ghana, the Volta Basin covers about 45 percent of the nation's total land surface.[1] Its northern section, which lies above the upper part of Lake Volta, rises to a height of 150 to 215 metres (492 to 705 ft) above sea level.[1] Elevations of the Konkori Scarp to the west and the Gambaga Scarp to the north reach from 300 to 460 metres (980 to 1,510 ft).[1] To the south and the southwest, the basin is less than 300 metres (980 ft).[1] The Kwahu Plateau marks the southern end of the basin, and forms a natural part of the Ashanti Uplands.

The basin is characterized by poor soil, generally of Voltaian sandstone.[1] Annual rainfall averages between 1,000 and 1,140 millimetres (39 and 45 in).[1] The most widespread vegetation type is savanna, the woodlands of which, depending on local soil and climatic conditions, may contain such trees as red ironwood and shea.[1]

The basin's population, principally farmers, is low in density, especially in the central and northwestern areas of the basin, where tsetse flies are common.[1] Archeological finds indicate that the region was once more heavily populated.[1] Periodic burning occurred over extensive areas for perhaps more than a millennium, exposing the soil to excessive drying and erosion, rendering the area less attractive to cultivators.[1]

In contrast with the rest of the region are the Afram Plains, located in the southeastern corner of the basin.[1] Here the terrain is low, averaging 60 to 150 metres (200 to 490 ft) in elevation, and annual rainfall is between 1,140 millimetres (45 in) and about 1,400 millimetres (55 in).[1] Near the Afram River, much of the surrounding countryside is flooded or swampy during the rainy seasons.[1] With the creation of Lake Volta (8,500 square kilometres (3,300 sq mi) in area) in the mid-1960s, much of the Afram Plains was submerged.[1] Despite the construction of roads to connect communities displaced by the lake, road transportation in the region remains poor.[1] Renewed efforts to improve communications, to enhance agricultural production, and to improve standards of living began in earnest in the mid-1980s.[1]

High plains

The general terrain in the northern and northwestern part of Ghana outside the Volta Basin consists of a dissected plateau, which averages between 150 and 300 metres (490 and 980 ft) in elevation and, in some places, is even higher.[1] Rainfall averages between 1,000 and 1,150 millimetres (39 and 45 in) annually, although in the northwest it is closer to 1,350 millimetres (53 in).[1] Soils in the high plains are more arable than those in the Volta Basin, and the population density is considerably higher.[1] Grain and cattle production are the major economic activities in the high plains of the northern region.[1]

Since the mid-1980s, when former United States President Jimmy Carter's Global 2000 program adopted Ghana as one of a select number of African countries whose local farmers were to be educated and financially supported to improve agricultural production, there has been a dramatic increase in grain production in northern Ghana.[1] The virtual absence of tsetse flies in the region has led to increased livestock raising as a major occupation in the north.[1] The region is Ghana's largest producer of cattle.[1]

Rivers and lakes

Ghana is drained by a large number of streams and rivers.[1] In addition, there are a number of coastal lagoons, the huge man-made Lake Volta, and Lake Bosumtwi, southeast of Kumasi, which has no outlet to the sea.[1] In the wetter south and southwest areas of Ghana, the river and stream pattern is denser, but in the area north of the Kwahu Plateau, the pattern is much more open, making access to water more difficult.[1] Several streams and rivers also dry up or experience reduced flow during the dry seasons of the year, while flooding during the rainy seasons is common.[1]

The major drainage divide runs from the southwest part of the Akwapim-Togo Ranges northwest through the Kwahu Plateau and then irregularly westward to the Ivory Coast border.[1] Almost all the rivers and streams north of this divide form part of the Volta system.[1] Extending about 1,600 kilometres (990 mi) in length and draining an area of about 388,000 square kilometres (150,000 sq mi), of which about 158,000 square kilometres (61,000 sq mi) lie within Ghana, the Volta and its tributaries, such as the Afram River and the Oti River, drain more than two thirds of Ghana.[1] To the south of the divide are several smaller, independent rivers.[1] The most important of these are the Pra River, the Tano River, the Ankobra River, the Birim River, and the Densu River.[1] With the exception of smaller streams that dry up in the dry seasons or rivers that empty into inland lakes, all the major rivers in Ghana flow into the Gulf of Guinea directly or as tributaries to other major rivers.[1] The Ankobra and Tano are navigable for considerable distances in their lower reaches.[1]

Navigation on the Volta River has changed significantly since 1964.[1] Construction of the dam at Akosombo, about 80 kilometres (50 mi) upstream from the coast, created the vast Lake Volta and the associated hydroelectric project.[1] Arms of the lake extended into the lower-lying areas, forcing the relocation of 78,000 people to newly created townships on the lake's higher banks.[1] The Black Volta River and the White Volta River flow separately into the lake.[1] Before their confluence was submerged, the rivers came together in the middle of Ghana to form the main Volta River.[1]

The Oti River and the Daka River, the principal tributaries of the Volta in the eastern part of Ghana, and the Pru River, the Sene River, and the Afram River, major tributaries to the north of the Kawhu Plateau, also empty into flooded extensions of the lake in their river valleys.[1] Lake Volta is a rich source of fish, and its potential as a source for irrigation is reflected in an agricultural mechanization agreement signed in the late 1980s to irrigate the Afram Plains.[1] The lake is navigable from Akosombo through Yeji in the middle of Ghana.[1] A 24-metre (79 ft) pontoon was commissioned in 1989 to link the Afram Plains to the west of the lake with the lower Volta region to the east.[1] Hydroelectricity generated from Akosombo supplies Ghana, Togo, and Benin.[1]

On the other side of the Kwahu Plateau from Lake Volta are several river systems, including the Pra, Ankobra, Tano and Densu.[1] The Pra is the easternmost and the largest of the three principal rivers that drain the area south of the Volta divide.[1] Rising south of the Kwahu Plateau and flowing southward, the Pra enters the Gulf of Guinea east of Takoradi.[1] In the early part of the twentieth century, the Pra was used extensively to float timber to the coast for export.[1] This trade is now carried by road and rail transportation.[1]

The Ankobra, which flows to the west of the Pra, has a relatively small drainage basin.[1] It rises in the hilly region of Bibiani and flows in a southerly direction to enter the gulf just west of Axim.[1] Small craft can navigate approximately 80 kilometres (50 mi) inland from its mouth.[1] At one time, the Ankobra helped transport machinery to the gold-mining areas in the vicinity of Tarkwa.[1] The Tano, which is the westernmost of the three rivers, rises near Techiman in the centre of the country.[1] It also flows in a southerly direction, and it empties into a lagoon in the southeast corner of Ivory Coast.[1] Navigation by steam launch is possible on the southern sector of the Tano for about 70 kilometres (43 mi).[1]

A number of rivers are found to the east of the Pra.[1] The two most important are the Densu and Ayensu, both of which rise in the Atewa Range, and which are important as sources of water for Accra and Winneba respectively.[1] The country has one large natural lake, Lake Bosumtwi, located about 32 kilometres (20 mi) southeast of Kumasi.[1] It occupies the steep-sided meteoric crater and has an area of about 47 square kilometres (18 sq mi).[1] A number of small streams flow into Lake Bosumtwi, but there is no drainage from it.[1] Apart from providing an opportunity for fishing for local inhabitants, the lake serves as a tourist attraction.[1]

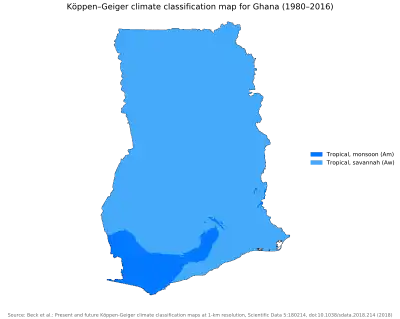

Climate

The country's warm, humid climate has an annual mean temperature between 26 and 29 °C (79 and 84 °F).[3] Variations in the principal elements of temperature, rainfall, and humidity that govern the climate are influenced by the movement and interaction of the dry tropical continental air mass, or the harmattan, which blows from the northeast across the Sahara, and the opposing tropical maritime or moist equatorial system.[3] The cycle of the seasons follows the apparent movement of the sun back and forth across the equator.[3]

During summer in the northern hemisphere, a warm and moist maritime air mass intensifies and pushes northward across the country.[3] A low-pressure belt, or intertropical front, in the airmass brings warm air, rain, and prevailing winds from the southwest.[3] As the sun returns south across the equator, the dry, dusty, tropical continental front, or harmattan, prevails.[3] Climatic conditions across the country are hardly uniform.[3] The Kwahu Plateau, which marks the northernmost extent of the forest area, also serves as an important climatic divide.[3] To its north, two distinct seasons occur.[3] The harmattan season, with its dry, hot days and relatively cool nights from November to late March or April, is followed by a wet period that reaches its peak in late August or September.[3] To the south and southwest of the Kwahu Plateau, where the annual mean rainfall from north to south ranges from 1,250 to 2,150 millimetres (49 to 85 in), four separate seasons occur.[3] Heavy rains fall from about April through late June.[3] After a relatively short dry period in August, another rainy season begins in September and lasts through November, before the longer harmattan season sets in to complete the cycle.[3]

The extent of drought and rainfall varies across the country.[3] To the south of the Kwahu Plateau, the heaviest rains occur in the Axim area in the southwest corner of Ghana.[3] Farther to the north, Kumasi receives an average annual rainfall of about 1,400 millimetres (55 in), while Tamale in the drier northern savanna receives rainfall of 1,000 millimetres (39 in) per year.[3] From Takoradi eastward to the Accra Plains, including the lower Volta region, rainfall averages only 750 to 1,000 millimetres (30 to 39 in) a year.[3]

Temperatures are usually high at all times of the year throughout the country.[3] At higher elevations, temperatures are more comfortable.[3] In the far north, temperature highs of 31 °C (88 °F) are common.[3] The southern part of the country is characterized by generally humid conditions.[3] This is particularly so during the night, when 95 to 100 percent humidity is possible.[3] Humid conditions also prevail in the northern section of the country during the rainy season.[3] During the harmattan season, however, humidity drops as low as 25 percent in the north.[3]

Natural hazards

Dry, dusty, harmattan winds occur from January to March. Ghana is also prone to droughts, and was severely affected by floods in 2007 and 2009.[4]

Environmental issues

Environmental issues include recurrent drought in the north, severely affecting agricultural activities, deforestation, overgrazing, soil erosion, poaching and habitat destruction threatens wildlife populations, water pollution, and inadequate supplies of potable water

International agreements (ratified):

Biodiversity, Climate Change, Desertification, Endangered Species, Environmental Modification, Law of the Sea, Ozone Layer Protection, Ship Pollution, Tropical Timber 83, Tropical Timber 94, Wetlands.

International agreements (signed, but not ratified)

Other

Volta Lake, the largest artificial lake in the world, extends from the Akosombo Dam in southeastern Ghana to the town of Yapei, 520 kilometers (323 mi) to the north. The lake generates electricity, provides inland transportation, and is a potentially valuable resource for irrigation and fish farming.

Ghana has a large and well-preserved national park system that includes Kakum National Park in the Central Region, Mole National Park in the Northern Region, Digya National Park along the western bank of the Volta Lake.

Extreme points

This is a list of the extreme points of Ghana, the points that are farther north, south, east or west than any other location.

- Northernmost point – the point at which the border with Burkina Faso enters the Morbira river immediately south of the Burkinabè village of Kanhiré, Upper East Region

- Easternmost point – the southernmost section of the border with Togo, Volta Region*

- Southernmost point – Cape Three Points, Western Region

- Westernmost point - the point where the border with Ivory Coast enters the Manzan river, Western Region

- Note: Ghana does not have an easternmost point, the border at this section being defined along the line of longitude at 1°12'05.73"E[5]

Gallery

- Landscapes and climates of Ghana

Springs and waterfalls in the Volta region

Springs and waterfalls in the Volta region

Wetlands and western reef herons in the Greater Accra region

Wetlands and western reef herons in the Greater Accra region

.jpg.webp) Tropical evergreen rainforest at Ankasa, Western Region, Ghana

Tropical evergreen rainforest at Ankasa, Western Region, Ghana

See also

References

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Owusu-Ansah, David (1995). Berry, LaVerle (ed.). Ghana: a country study (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 62–72. ISBN 0-8444-0835-2. OCLC 32508385.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Owusu-Ansah, David (1995). Berry, LaVerle (ed.). Ghana: a country study (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 62–72. ISBN 0-8444-0835-2. OCLC 32508385. - "Ghana". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. August 23, 2021. Retrieved September 3, 2021.

-

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Owusu-Ansah, David (1995). Berry, LaVerle (ed.). Ghana: a country study (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-8444-0835-2. OCLC 32508385.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: Owusu-Ansah, David (1995). Berry, LaVerle (ed.). Ghana: a country study (3rd ed.). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. pp. 72–73. ISBN 0-8444-0835-2. OCLC 32508385. - Heavy floods caused loss of life and widespread damage in 2007 and 2009. See also 2007 African floods#Ghana and 2009 West Africa floods.

- International Boundary Study, "Ghana Togo Boundary", No.126, 6 September 1972