Airbus A340

The Airbus A340 is a long-range, wide-body passenger airliner that was developed and produced by Airbus. In the mid-1970s, Airbus conceived several derivatives of the A300, its first airliner, and developed the A340 quadjet in parallel with the A330 twinjet. In June 1987, Airbus launched both designs with their first orders and the A340-300 took its maiden flight on 25 October 1991. It was certified along with the A340-200 on 22 December 1992 and both versions entered service in March 1993 with launch customers Lufthansa and Air France. The larger A340-500/600 were launched on 8 December 1997; the A340-600 flew for the first time on 23 April 2001 and entered service on 1 August 2002.

| A340 | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| An A340 of Air France, landing at Bolívar International | |

| Role | Wide-body jet airliner |

| National origin | Multi-national |

| Manufacturer | Airbus |

| First flight | 25 October 1991 |

| Introduction | 15 March 1993 with Lufthansa & Air France |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | Lufthansa Mahan Air Edelweiss Air Swiss International Air Lines |

| Produced | 1991–2012[1] |

| Number built | 380 (377 delivered to airlines)[2] |

| Developed from | Airbus A300 |

Keeping the eight-abreast economy cross-section of the A300, the early A340-200/300 has a similar airframe to the A330. Differences include four 151 kN (34,000 lbf) CFM56s instead of two high-thrust turbofans to bypass ETOPS restrictions on trans-oceanic routes, and a three-leg main landing gear instead of two for a heavier 276 t (608,000 lb) MTOW. Both airliners have fly-by-wire controls, which was first introduced on the A320, as well as a similar glass cockpit. The later A340-500/600 have a larger wing and are powered by 275 kN (62,000 lbf) Rolls-Royce Trent 500 for a heavier 380 t (840,000 lb) MTOW.

The shortest A340-200 measured 59.4 m (195 ft), and with a 12,400 km range (6,700 nmi; 7,700 mi) with 210–250 seats in 3-class. The most common A340-300 reached 63.7 m (209 ft) to accommodate 250–290 passengers and could cover 13,500 km (7,300 nmi; 8,400 mi). The A340-500 was 67.9 m (223 ft) long to seat 270–310 over 16,670 km (9,000 nmi; 10,360 mi), the longest-range airliner at the time. The longest A340-600 was stretched to 75.4 m (247 ft), then the longest airliner, to accommodate 320–370 passengers over 14,450 km (7,800 nmi; 8,980 mi).

As improving engine reliability allowed ETOPS operations for almost all routes, more economical twinjets have replaced quadjets on many routes. On 10 November 2011, Airbus announced that the production reached its end, after 380 orders had been placed and 377 delivered from Toulouse, France. The A350 is its successor; the McDonnell Douglas MD-11 and the Boeing 777 were its main competitors. By the end of 2021, the global A340 fleet had completed more than 2.5 million flights over 20 million block hours and carried over 600 million passengers with no fatalities. As of March 2023, there were 203 A340 aircraft in service with 45 operators worldwide. Lufthansa is the largest A340 operator with 27 aircraft in its fleet.

Development

Background

When Airbus designed the Airbus A300 during the 1970s it envisioned a broad family of airliners to compete against Boeing and McDonnell Douglas, two established US aerospace manufacturers. From the moment of formation, Airbus had begun studies into derivatives of the Airbus A300B in support of this long-term goal.[3] Prior to the service introduction of the first Airbus airliners, Airbus had identified nine possible variations of the A300 known as A300B1 to B9.[4] A tenth variation, conceived in 1973, later the first to be constructed, was designated the A300B10.[5] It was a smaller aircraft that would be developed into the long-range Airbus A310. Airbus then focused its efforts on the single-aisle market, which resulted in the Airbus A320 family, which was the first digital fly-by-wire commercial aircraft. The decision to work on the A320, instead of a four-engine aircraft proposed by the Germans, created divisions within Airbus.[5] As the SA or "single aisle" studies (which later became the successful Airbus A320) underwent development to challenge the successful Boeing 737 and Douglas DC-9 in the single-aisle, narrow-body airliner market, Airbus turned its focus back to the wide-body aircraft market.

The A300B11,[6] a derivative of the A310, was designed upon the availability of "ten ton" thrust engines.[7] Using four engines, it would seat between 180 and 200 passengers, and have a range of 6,000 nautical miles (11,000 km; 6,900 mi).[8] It was deemed a replacement for the less-efficient Boeing 707s and Douglas DC-8s still in service.[7] The A300B11 was joined by another design, the A300B9, which was a larger derivative of the A300. The B9 was developed by Airbus from the early 1970s at a slow pace until the early 1980s. It was essentially a stretched A300 with the same wing, coupled with the most powerful turbofan engine available at the time.[7] It was targeted at the growing demand for high-capacity, medium-range, transcontinental trunk routes.[7] The B9 offered the same range and payload as the McDonnell Douglas DC-10, but it used between 25%[7] and 38%[9] less fuel. The B9 was therefore considered a replacement for the DC-10 and the Lockheed L-1011 Tristar.[10]

To differentiate the programme from the SA studies, the B9 and B11 were redesignated the TA9 and TA11 (SA standing for "single aisle" and TA standing for "twin aisle").[6] In an effort to save development costs, it was decided that the two would share the same wing and airframe; the projected savings were estimated at US$500 million (about £490 million or €495 million).[11] The adoption of a common wing structure also had one technical advantage: the TA11's outboard engines could counteract the weight of the longer-range model by providing bending relief.[7] Another factor was the split preference of those within Airbus and, more importantly, prospective airliner customers. Airbus vice president for strategic planning, Adam Brown, recalled,

North American operators were clearly in favour of a twin[jet], while Asians wanted a quad[jet]. In Europe, opinion was split between the two. The majority of potential customers were in favour of a quad despite the fact, in certain conditions, it is more costly to operate than a twin. They liked that it could be ferried with one engine out, and could fly 'anywhere'— ETOPS (extend-range twin-engine operations) hadn't begun then.[12][13]

Design effort

The first specifications of the TA9 and TA11 were released in 1982.[14] While the TA9 had a range of 3,300 nautical miles (6,100 km; 3,800 mi), the TA11 range was up to 6,830 nautical miles (12,650 km; 7,860 mi).[14] At the same time, Airbus also sketched the TA12, a twin-engine derivative of the TA11, which was optimised for flights of a 2,000 nautical miles (3,700 km; 2,300 mi) lesser range.[14] By the time of the Paris Air Show in June 1985, more refinements had been made to the TA9 and TA11, including the adoption of the A320 flight deck, fly-by-wire (FBW) flight control system and side-stick control.[15] Adopting a common cockpit across the new Airbus series allowed operators to make significant cost savings; flight crews would be able to transition from one to another after one week of training.[16] The TA11 and TA12 would use the front and rear fuselage sections of the A310.[17] Components were modular and also interchangeable with other Airbus aircraft where possible[16] to reduce production, maintenance, and operating costs.

Airbus briefly considered a variable camber wing; the concept was that the wing could change its profile to produce the optimum shape for a given phase of flight. Studies were carried out by British Aerospace (BAe) at Hatfield and Bristol. Airbus estimated this would yield a 2% improvement in aerodynamic efficiency.[18] However, the plan was later abandoned on grounds of cost and difficulty of development.[6]

Airbus had held discussions with McDonnell Douglas to jointly produce the aircraft, which would have been designated as the AM 300.[19] This aeroplane would have combined the wing of the A330 with the fuselage of the McDonnell Douglas MD-11.[19] However, talks were terminated as McDonnell Douglas insisted on the continuation of its trijet heritage.[20] Although from the start it was intended that the A340 would be powered by four CFM56-5 turbofans, each capable of 25,000 pounds-force (110 kN),[21] Airbus had also considered developing the aircraft as a trijet due to the limited power of engines available at the time, namely the Rolls-Royce RB211-535 and Pratt & Whitney JT10D-232[22] (redesignated PW2000 in December 1980).

As refinements in the A340's design proceeded, a radical new engine option, the IAE SuperFan, was offered by International Aero Engines, a group comprising Rolls-Royce, Pratt & Whitney, Japanese Aero Engines Corporation, Fiat and MTU Aero Engines (MTU). The engine nacelles of the superfan engine consisted of provisions to allow a large fan near the rear of the engine. As a result of the superfan cancellation by IAE, the CFM56-5C4 was used as the sole engine choice instead of being an alternate option as originally envisioned. The later, longer-range versions, namely the A340-500 and −600, are powered by Rolls-Royce Trent 500 engines.

On 27 January 1986, the Airbus Industrie Supervisory Board held a meeting in Munich, West Germany, after which board-chairman Franz Josef Strauß released a statement,

Airbus Industrie is now in a position to finalise the detailed technical definition of the TA9, which is now officially designated the A330, and the TA11, now called the A340, with potential launch customer airlines, and to discuss with them the terms and conditions for launch commitments.[15]

The designations were originally reversed and were switched so the quad-jet airliner would have a "4" in its name. On 12 May 1986, Airbus dispatched fresh sale proposals to five prospective airlines including Lufthansa and Swissair.[15]

Production and testing

In preparations for production of the A330/A340, Airbus's partners invested heavily in new facilities. Filton was the site of BAe's £7 million investment in a three-storey technical centre with an extra 15,000 square metres (160,000 sq ft) of floor area.[23] BAe also spent £5 million expanding the Broughton wing production plant by 14,000 m2 (150,000 sq ft)[23] to accommodate a new production line. However, France saw the biggest changes with Aérospatiale starting construction of a new Fr.2.5 billion ($411 million) assembly plant, adjacent to Toulouse-Blagnac Airport, in Colomiers.[24] By November 1988, the first 21 m (69 ft) pillars were erected for the new Clément Ader assembly hall.[24] The assembly process, meanwhile, would feature increased automation with holes for the wing-fuselage mating process drilled by eight robots.[25] The use of automation for this particular process saved Airbus 20% on labour costs and 5% on time.[25]

British Aerospace accepted £450 million funding from the UK government, short of the £750 million originally requested.[26] Funds from the French and West German governments followed thereafter. Airbus also issued subcontracts to companies in Austria, Australia, Canada, China, Greece, Italy, India, Japan, South Korea, Portugal, the United States, and Yugoslavia.[27] The A330 and A340 programmes were jointly launched on 5 June 1987,[28] just prior to the Paris Air Show. The program cost was $3.5 billion with the A330, in 2001 dollars.[29] The order book then stood at 130 aircraft from 10 customers, apart from the above-mentioned Lufthansa and International Lease Finance Corporation (ILFC). Eighty-nine of the total orders were A340 models.[26] At McDonnell Douglas, ongoing tests of the MD-11 revealed a significant shortfall in the aircraft's performance. An important carrier, Singapore Airlines (SIA), required a fully laden aircraft that could fly from Singapore to Paris, against strong headwinds during mid-winter in the northern hemisphere.[30] The MD-11, according to test results, would experience fuel starvation over the Balkans.[30] Due to the less-than-expected performance figures, SIA cancelled its 20-aircraft MD-11 order on 2 August 1991, and ordered 20 A340-300s instead.[31] A total of 200 MD-11s were sold, versus 380 A340s.[20]

The first flight of the A340 occurred on 21 October 1991,[20] marking the start of a 2,000-hour test flight programme involving six aircraft.[32] From the start, engineers noticed that the wings were not stiff enough to carry the outboard engines at cruising speed without warping and fluttering. To alleviate this, an underwing bulge called a plastron was developed to correct airflow problems around the engine pylons[33] and to add stiffness. European JAA certification was obtained on 22 December 1992; the FAA followed on 27 May 1993.[34] In 1992, unit cost of an A340-200 was US$105M and US$110M for an A340-300.[35] (equivalent to $185 million in 2021 dollars).

Entry into service and demonstration

The first A340, a −200, was delivered to Lufthansa on 2 February 1993 and entered service on 15 March.[34] The 228-seat airliner was named Nürnberg.[36] The first A340-300, the 1000th Airbus, was delivered to Air France on 26 February, the first of nine it planned to operate by the end of the year.[34] Air France replaced its Boeing 747s with A340s on its Paris–Washington D.C. route, flying four times weekly.[37] Lufthansa intended to replace aging DC-10s with the A340s on Frankfurt–New York services.

On 16 June 1993, an A340-200 dubbed the World Ranger flew from the Paris Air Show to Auckland, New Zealand in 21 hours 32 minutes and back in 21 hours 46 minutes after a five-hour stop; this was the first non-stop flight between Europe and New Zealand and the longest non-stop flight by an airliner at the time.[38] The 19,277 km (10,409 nmi; 11,978 mi) flight from Paris to Auckland broke six world records with 22 persons and five center tanks.[39] Taking off at 11:58 local time, it arrived back in Paris 48 hours and 22 minutes later, at 12:20.[39][40] This record held until 1997 when a Boeing 777-200ER flew 20,044 km (10,823 nmi; 12,455 mi) from Seattle to Kuala Lumpur.[41]

Stretch: -500/-600 variants

Formulated in 1991, the A340-400X concept was a simple 12-frame, 20 ft 10 in (6.35 m) stretch of the −300 from 295 to 335 passengers with the MTOW increased to 553,360 to 588,600 lb (251 to 267 t) and the range decreased by 1,390 to 10,930 km (750 to 5,900 nmi).[42] CFM International was then set to develop a new engine for $1–1.5 billion that generated a thrust rating between the 150 kN (34,000 lbf) CFM56 and the 315–400 kN (70–90,000 lbf) GE90.[43] In 1994, Airbus was studying a heavier A340 Advanced with a reinforced wing and a selection of 178 kN (40,000 lbf) engines; these included the Pratt & Whitney advanced ducted propulsor, CFM International CFMXX or Rolls-Royce RB411, to a −300 stretch for 50 more passengers over the same range, a −300 with the −200 range and a −200 with more range. These models were slated to be introduced in 1996.[44] In 1995, the A340-400 was slated for introduction in the year 2000, seating 380 passengers with a 300 t (660,000 lb) take-off weight.[45]

In April 1996, GE Aviation obtained an exclusivity for the 13,000 km (7,000 nmi; 8,100 mi) 375-passenger −600 stretch with 226 kN (51,000 lbf) engines, above the 225.5 kN (50,700 lbf) limit of the CFM International engines made in partnership with SNECMA and dropping the 191 kN (43,000 lbf) CFMXX.[46] The −600 would be stretched by 20–22 frames to 75 m (246 ft), unit thrust was raised from 227 kN (51,000 lbf) to 249 kN (56,000 lbf) and maximum takeoff weight would be increased to 330 t (730,000 lb). The wing area would increase by 56 m2 (600 sq ft) to 420 m2 (4,500 sq ft) through a larger chord needing a three-frame centre fuselage insert and retaining the existing front and rear spars, and a span increased by 3.5 to 63.8 m (11 to 209 ft), alongside a 25% increase in wing fuel capacity and four wheels replacing the centre twin-wheel bogie. A −500 with the larger wing and engines and three extra frames for 310 passengers would cover 15,725 km (9,770 mi; 8,490 nmi) to replace the smaller 14,800 km (9,200 mi; 8,000 nmi) range A340-200. At least $1 billion would be needed to develop the airframe, excluding the $2 billion required for engine development supported by the engine manufacturer. A 12 frame −400 simple stretch would cover 11,290 km (6,100 nmi; 7,020 mi) with 340 passengers in a three-class configuration.[47]

It was enlarged by 40% to compete with the then in-development 777-300ER/200LR: the wing would be expanded with a tapered wing box insert along the span extension, it would have enlarged horizontal stabilizers and the larger A330-200 fin and it would need 222–267 kN (50–60,000 lbf) of unit thrust. The ultra-long-haul 1.53 m (5.0 ft) -500 stretch would seat 316 passengers, a little more than the −300, over 15,355 km (8,290 nmi; 9,540 mi), while the 10.07 m (33.0 ft) -600 stretch would offer a 25% larger cabin for 372 passengers over a range of 13,700 km (7,400 nmi; 8,500 mi).[48] MTOW was increased to 356 t (785,000 lb).[49]

Unwilling to commit to a $1 billion development without good return on investment prospects and a second application, in 1997 GE Aviation stopped exclusivity talks for GE90 scaled down to 245–290 kN (55–65,000 lbf), leaving Rolls-Royce proposing a more cost-effective Rolls-Royce Trent variant needing less development and Pratt & Whitney suggesting a PW2000 advanced ducted propulsor, a PW4000 derivative or a new geared turbofan.[50] In June 1997, the 250 kN (56,000 lbf) Rolls-Royce Trent 500 was selected, with growth potential to 275 kN (62,000 lbf), derived from the A330 Rolls-Royce Trent 700 and the B777 Rolls-Royce Trent 800 with a reduced fan diameter and a new LP turbine, for a 7.7% lower TSFC than the 700. Airbus claims 10% lower operating costs per seat than the −300, 3% below those of what Boeing was then advertising for the 777-300X.[51] The $2.9 billion program was launched in December 1997 with 100 commitments from seven customers worth $3 billion, aiming to fly the first −600 in January 2001 and deliver it from early 2002 to capture at least half of the 1,500 sales forecast in the category through 2010.[52]

In 1998, the −600 stretch was stabilised at 20 frames for 10.6 m (35 ft), the MTOW rose to 365 t (805,000 lb) and the unit thrust to 52,000 to 60,000 lbf (230 to 270 kN), keeping the Trent 700 2.47 m (8.1 ft) fan diameter with its scaled IP and HP compressors and the high-speed, low-loading HP and IP turbines of the Trent 800.[53]

| Period | 1991[42] | 1994[44] | 1995[45] | 1996[48] | 1998[53] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit thrust | 178 kN (40,000 lbf) | 267 kN (60,000 lbf) | 267 kN (60,000 lbf) | ||

| Stretch | 12 frames (40 pax) | 50 pax | 20–22 frames, 10.07 m (33.0 ft) | 20 frames, 10.6 m (35 ft) | |

| Passengers | 335 | 380 | 375 | 380 | |

| Range | 10,900 km (5,900 nmi; 6,800 mi) | same as −300 | 13,700 km (7,400 nmi; 8,500 mi) | 13,900 km (7,500 nmi; 8,600 mi) | |

| MTOW | 267.0 t (588,600 lb) | 300 t (660,000 lb) | 356 t (785,000 lb) | 365 t (805,000 lb) |

Despite the −500/600 introduction, sales slowed in the 2000s as the Boeing 777-200LR/-300ER dominated the long-range 300–400 seat market. The A340-500IGW/600HGW high gross weight variants did not arouse much sales interest.[54][55][56] In January 2006, Airbus confirmed it had studied an A340-600E (Enhanced) that was more fuel-efficient than earlier A340s, reducing the per-seat fuel consumption by 8–9% compared to the −600. This model would become more competitive with the Boeing 777-300ER by utilizing new Trent 1500 engines and technologies from the A350 initial design.[54]

At 380 passengers, the advertised three-class seating of the −600 was well above the real world average of 323 seats, while the B777-300ER is advertised for 365 and offers 332, impacting seat costs. By 2018, a 2006 -600 was worth $18M and a 2003 one $10M, projected to fall to $7M in 2021 with a $200,000/month lease rate falling to $180,000 in 2021; its D check cost $4.5M and its engine overhaul $3–6M.[57]

End of production

In 2005, 155 B777s were ordered against 15 A340s: twin engine ETOPS restrictions were overcome by lower operating costs compared to quad jets and the relaxation of ETOPS requirements for the A330, 777, and other twinjets.[58] In 2007, Airbus predicted that another 127 A340 aircraft would likely be produced through 2016, the projected end of production.[59]

In 2011, the unit cost of an A340-300 was US$238.0M ($309.6M today), US$261.8M for an A340-500 ($340.6M today) and US$275.4M for an A340-600 ($358.3M today).[60] On 10 November 2011, Airbus announced the end of the A340 program. At that time, the company indicated that all firm orders had been delivered.[61] The decision to terminate the program came as A340-500/600 orders came to a halt, with analyst Nick Cunningham pointing out that the A340 "was too heavy and there was a big fuel burn gap between the A340 and Boeing's 777". Bertrand Grabowski, managing director of aircraft financier DVB Bank SE, noted "in an environment where the fuel price is high, the A340 has had no chance to compete against similar twin engines, and the current lease rates and values of this aircraft reflect the deep resistance of any airlines to continue operating it".[54][55][56]

As a sales incentive amid low customer demand during the Great Recession, Airbus had offered buy-back guarantees to airlines that chose to procure the A340. By 2013, the resale value of an A340 declined by 30% over ten years, and both Airbus and Rolls-Royce were incurring related charges amounting to hundreds of millions of euros. Some analysts have expected the price of a flight-worthy, CFM56-powered A340 to drop below $10 million by 2023.[62]

Airbus could offer used A340s to airlines wishing to retire older aircraft such as the Boeing 747-400, claiming that the cost of purchasing and maintaining a second-hand A340 with increased seating and improved engine performance reportedly compared favourably to the procurement costs of a new Boeing 777.[63]

In 2013, as ultra-long range is a niche, the A340 was less attractive with best usage on long, thin routes, from hot-and-high airports or as interim air charter. A 10-year-old A340-300 had a base value of $35m and a market value of $24m, leading to $320,000/mo ($240,000–$350,000) lease rate, while a −500 is $425,000 and a −600 is leased $450,000 to $500,000 per month, versus $1.3m for a 777-300ER. The lighter A340-300 consumes 5% less fuel per trip with 300 passengers than the 312 passengers 777-200ER while the heavier A340-600 uses 12% more fuel than a 777-300ER.[64]

As an effort to support the A340's resale value, Airbus has proposed reconfiguring the aircraft's interior for a single class of 475 seats. As the Trent 500 engines are half the maintenance cost of the A340, Rolls-Royce proposed a cost-reducing maintenance plan similar to the company's existing program that reduced the cost of maintaining the RB211 engine powering Iberia's Boeing 757 freighters. Key to these programs is the salvaging, repair and reuse of serviceable parts from retired older engines.[65]

Airbus has positioned the larger versions of the A350, specifically the A350-900 and A350-1000, as the successors to the A340-500 and A340-600.

The ACJ340 is listed on the Airbus Corporate Jets website, as Airbus can convert retired A340 airliners to VIP transport configuration.[66]

Design

The Airbus A340 is a twin-aisle passenger airliner that was the first long-range Airbus,[67] powered by four turbofan jet engines.[68] It was developed with technology from earlier Airbus aircraft and their features like the A320 glass cockpit; it shares many components with the A330, notably identical fly-by-wire control systems and similar wings.[16][69] Its features and improvements were usually shared with the A330.[70] The four engines configuration avoided the ETOPS constraints such as more frequent inspections.

The A340 has a low cantilever wing; the A340-200/300 wing is virtually identical to that of the A330, with both engine pylons used while only the inboard one is used on the A330. The two engines for each wing provide a more distributed weight; and a more outboard engine weight for a lower wing root bending moment at equal TOW, allowing a higher wing limited MTOW for more range. The wings were designed and manufactured by BAe, which developed a long slender wing with a high aspect ratio for a higher aerodynamic efficiency.[71][lower-alpha 1]

The wing is swept back at 30 degrees, allowing a maximum operating Mach number of 0.86.[73][74] To reach a long span and high aspect ratio without a large weight penalty, the wing has relatively high thickness-to-chord ratio of 11.8%[75] or 12.8%.[76][lower-alpha 2] Jet airliners have thickness-to-chord ratios ranging from 9.4% (MD-11 or Boeing 747) to 13% (Avro RJ or 737 Classic).[77] Each wing also has a 2.74 m (9.0 ft) tall winglet instead of the wingtip fences found on earlier Airbus aircraft. The failure of the ultra-high-bypass IAE SuperFan, promising around 15% better fuel burn, led to wing upgrades to compensate.[78][79] Originally designed with a 56 m (184 ft) span, the wing was later extended to 58.6 m (192 ft) and finally to 60.3 m (198 ft).[78] This wingspan is similar to that of the larger Boeing 747-200, but with 35% less wing area.[73][74]

The A340 uses a modified A320 glass cockpit, with side-stick controls instead of a conventional yoke. The main instrument panel is dominated by six displays, cathode ray tube monitors initially then liquid crystal displays.[68] Flight information is directed via the Electronic Flight Instrument System (EFIS) and systems information through the Electronic Centralised Aircraft Monitor (ECAM).[80][81]

The aircraft monitors various sensors and automatically alerts the crew to any parameters outside of their normal range; pilots can also inspect individual systems. Electronic manuals are used instead of paper ones, with optional web-based updates. Maintenance difficulty and cost were reduced to half of that of the earlier and smaller Airbus A310.[82] Improved engine control and monitoring improved time on wing. The centralised maintenance computer can transmit real-time information to ground facilities via the onboard satellite-based ACARS datalink.[68][82] Heavy maintenance like structural changes remained unchanged, while cabin sophistications, like the in-flight entertainment, were increased over preceding airliners.[82]

The A340-200/300 is powered by four CFM56-5Cs with exhaust mixers

The A340-200/300 is powered by four CFM56-5Cs with exhaust mixers.jpg.webp) The A340-500/600 is powered by four larger Rolls-Royce Trent 500s with separate flows

The A340-500/600 is powered by four larger Rolls-Royce Trent 500s with separate flows

Operational history

The first variant of the A340 to be introduced, the A340-200, entered service with the launch customer, Lufthansa, in 1993. It was followed shortly thereafter by the A340-300 with its operator, Air France. Lufthansa's first A340, which had been dubbed Nürnberg (D-AIBA),[36] began revenue service on 15 March 1993.[34][83] Air Lanka (later renamed Sri Lankan Airlines) became the Asian launch customer of the Airbus A340; the airline received its first A340-300, registered (4R-ADA), in September 1994. British airline Virgin Atlantic was an early adopter of the A340; in addition to operating several A340-300 aircraft, Virgin Atlantic announced in August 1997 that it was to be the worldwide launch customer for the new A340-600.[84] The first commercial flight of the A340-600 was performed by Virgin in July 2002.[84]

Singapore Airlines ordered 17 A340-300s and operated them until October 2003. The A340-300s were purchased by Boeing as part of an order for Boeing 777s in 1999.[85] The airline then purchased five long-range A340-500s, which joined the fleet in December 2003. In February 2004, the airline's A340-500 performed the longest non-stop commercial air service in the world, conducting a non-stop flight between Singapore and Los Angeles.[86] In 2004, Singapore Airlines launched an even longer non-stop route using the A340-500 between Newark and Singapore, SQ 21, a 15,344 kilometres (8,285 nmi; 9,534 mi) journey that was the longest scheduled non-stop commercial flight in the world.[87] The airline continued to operate this route regularly until the airline decided to retire the type in favour of new A380 and A350 aircraft;[88] its last A340 flight was performed in late 2013.

The A340 was typically used by airlines as a medium-sized long-haul aircraft and was often a replacement for older Boeing 747s as it was more likely to be profitable compared to the larger and less efficient 747.[89] Airbus produced a number of A340s as large private jets for VIP customers, often to replace aging Boeing 747s in this same role. In 2008, Airbus launched a dedicated corporate jetliner version of the A340-200: one key selling point of this aircraft was a range of up to 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km). Airbus had built up to nine different customized versions of the A340 to private customers' specific demands prior to 2008.[90]

.jpg.webp)

The A340 has frequently been operated as a dedicated transport for heads of state. A pair of A340-300s were acquired from Lufthansa by the Flugbereitschaft of the German Air Force; they serve as VIP transports for the German Chancellor and other key members of the German government.[91] The A340 is also operated by the air transport division of the French Air and Space Force, where it is used as a strategic transport for troop deployments and supply missions, as well as to transport government officials.[92] A one-of-a-kind aircraft, the A340-8000, was originally built for Prince Jefri Bolkiah, brother of the Sultan of Brunei Hassanal Bolkiah. The aircraft was unused and stored in Hamburg until it was procured by Prince Al-Waleed bin Talal of the House of Saud,[93] and later sold to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi, then-President of Libya; the aircraft was operated by Afriqiyah Airways and was often referred to as Afriqiyah One.[94]

In 2008, jet fuel prices doubled compared to the year before; consequently, the A340's fuel consumption led airlines to reduce flight stages exceeding 15 hours. Thai Airways International cancelled its 17-hour, nonstop Bangkok–New York/JFK route on 1 July 2008, and placed its four A340-500s for sale. While short flights stress aircraft more than long flights and result in more frequent fuel-thirsty take-offs and landings, ultra-long flights require completely filled fuel tanks to ensure an adequate fuel supply upon landing. The higher weights in turn require a greater proportion of an aircraft's fuel fraction just to take off and to stay airborne. In 2008, Air France-KLM's chief executive Pierre-Henri Gourgeon disparagingly referred to the A340 as a "flying tanker with a few people on board".[95] While Thai Airways consistently filled 80% of the seats on its New York City–Bangkok flights, it estimated that, at 2008 fuel prices, it would need an impossible 120% of seats filled just to break even.[96] Other airlines also re-examined long-haul flights. In August 2008, Cathay Pacific issued a declaration expressing concern over the adverse impact of escalating fuel expenses on its trans-Pacific long-haul routes, emphasizing a disproportionate burden on these particular flights. Consequently, the airline outlined its strategic decision to curtail the frequency of such flights and reallocate its fleet to cater to shorter routes, notably those connecting Hong Kong and Australia. The company's primary objective, as articulated by the airline's CEO Tony Tyler, entailed a comprehensive network restructuring aimed at optimizing operational efficiency by ensuring flights were directed to destinations that would yield cost coverage and financial gain simultaneously.[97] Aviation Week noted that rapid performance increases of twin-engine aircraft has led to the detriment of four-engine types of comparable capacity such as the A340 and 747; at this point most 747s had accumulated significant flying hours before retirement in contrast to A340s which were relatively young when grounded.[98][99][100]

By 2014, Singapore Airlines had phased out the type, discontinuing SQ21 and SQ22, which had been the longest non-stop scheduled flights in the world. Emirates Airlines decided to accelerate the retirement of its A340 fleet, writing down the value of the A340-500 type to zero despite the oldest −500 only being 10 years old, with president Tim Clark saying they were "designed in the late 1990s with fuel at $25–30. They fell over at $60 and at $120 they haven't got a hope in hell".[101]

International Airlines Group, the parent of Iberia Airlines (which is also the operator of the last production A340 built), is overhauling its A340-600s for continued service for the foreseeable future, while it is retiring its A340-300s. The IAG overhaul featured improved conditions and furnishings in the business and economy classes; the business-class capacity was raised slightly while not changing the type's overall operating cost. Lufthansa, which operates both Airbus A340-300s and −600s, concluded that, while it is not possible to make the A340 more fuel efficient, it can respond to increased interest in business-class services by replacing first-class seats with more business-class seats to increase revenue.[101][102]

In 2013, Snecma announced that they planned to use the A340 as a flying testbed for the development of a new open rotor engine. This test aircraft is forecast to conduct its first flight in 2019. Open rotor engines are typically more fuel-efficient but noisier than conventional turbofan engines; introducing such an engine commercially has been reported as requiring significant legislative changes within engine approval authorities due to its differences from contemporary jet engines. The engine, partly based on the Snecma M88 turbofan engine used on the Dassault Rafale, is being developed under the European Clean Sky research initiative.[103][104]

In January 2021, Lufthansa, which was the largest remaining operator by then, announced that their entire Airbus A340-600 fleet will be retired with immediate effect and not return to service in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.[105] Ultimately, Lufthansa reactivated their A340-600s in late 2021,[106] while remaining committed to operating the smaller Airbus A340-300.[107][108] Later in 2021, a Portuguese charter carrier landed an A340 in Antarctica for the first time in history.[109]

As of December 2021, the global A340 fleet had carried over 600 million passengers and completed more than 2.5 million flights over 20 million block hours since its entry into service with 99 percent operational reliability[110] and zero fatal accidents.[111]

Variants

| ICAO code[112] | Model(s) |

|---|---|

| A342 | A340-200 |

| A343 | A340-300 |

| A345 | A340-500 |

| A346 | A340-600 |

There are four variants of the A340. The A340-200 and A340-300 were launched in 1987 with introduction into service in March 1993 for the −200. The A340-500 and A340-600 were launched in 1997 with introduction into service in 2002. All variants were available in a corporate version.

A340-200

The −200 is one of two initial versions of the A340; it has seating for 261 passengers in a three-class cabin layout with a range of 13,800 kilometres (7,500 nmi; 8,600 mi) or seating for 240 passengers also in a three-class cabin layout for a range of 15,000 kilometres (8,100 nmi; 9,300 mi).[113] This is the shortest version of the family and the only version with a wingspan measuring greater than its fuselage length. It is powered by four CFMI CFM56-5C4 engines and uses the Honeywell 331–350[A] auxiliary power unit (APU).[114] It initially entered service with Air France in May 1993. Due to its large wingspan, four engines, low capacity and general inferiority to the larger and more improved A340-300, the −200 proved very unpopular with mainstream airlines. Only 28 A340-200s were produced. The closest Boeing competitor is the Boeing 767-400ER.

One version of this type (referred to by Airbus as the A340-8000) was ordered by the prince Jefri Bolkiah, with the request for a non-stop range of 15,000 kilometres (8,100 nmi; 9,300 mi). This A340-8000, in the Royal Brunei Airlines livery had an increased fuel capacity, an MTOW of 275 tonnes (606,000 lb), similar to the A340-300, and minor reinforcements to the undercarriage. It is powered by the 150 kilonewtons (34,000 lbf) thrust CFM56-5C4s similar to the −300E. Only one A340-8000 was produced. Besides the −8000, some A340-200s are used for VIP or military use; these include Royal Brunei Airlines, Qatar Amiri Flight, Arab Republic of Egypt Government, Royal Saudi Air Force, Jordan and the French Air and Space Force. Following the −8000, other A340-200s were later given performance improvement packages (PIPs) that helped them achieve similar gains in capability as to the A340-8000. Those aircraft are labeled A340-213X. The range for this version is 15,000 kilometres (8,100 nmi; 9,300 mi).

As of October 2022, all active remaining A340-200s still flying were VIP or government planes. Conviasa operated the world's last commercial A340-200. The aircraft's last flight was documented in March 2022 before being scrapped.[115]

A340-300

The A340-300 flies 295 passengers in a typical three-class cabin layout over 6,700 nautical miles (12,400 km; 7,700 mi). This is the initial version, having flown on 25 October 1991, and it entered service with Lufthansa and Air France in March 1993. It is powered by four CFMI CFM56-5C engines and uses the Honeywell 331–350[A] APU,[114] similar to the version used on the −200. The A340-300 was superseded by the A350-900.[116] Its closest competitor was the Boeing 777-200ER.[117] A total of 218 -300s were delivered.

The A340-300E, often mislabelled as A340-300X, has an increased MTOW of up to 275 tonnes (606,000 lb) and is powered by the more powerful 34,000 lbf (150 kN) thrust CFMI CFM56-5C4 engines. Typical range with 295 passengers is between 7,200 and 7,400 nautical miles (13,300 and 13,700 km; 8,300 and 8,500 mi). The largest operator of this type is Lufthansa, who has operated a fleet of 30 aircraft. The A340-300 Enhanced is the latest version of this model and was first delivered to South African Airways in 2003, with Air Mauritius receiving the A340-300 Enhanced into its fleet in 2006. It received newer CFM56-5C4/P engines and improved avionics and fly-by-wire systems developed for the A340-500 and −600.

As of July 2018, there were 96 Airbus A340-300s in airline service.[118]

A340-500

.jpg.webp)

When the A340-500 was introduced, it was the world's longest-range commercial airliner. It first flew on 11 February 2002 and was certified on 3 December 2002. Air Canada was supposed to be the launch customer, but filed for bankruptcy in January 2003, delaying delivery to March. This allowed early deliveries to the new launch customer, Emirates, allowing the carrier to launch nonstop service from Dubai to New York—its first route in the Americas. The A340-500 can fly 313 passengers in a three-class cabin layout over 16020 km (8650 nm). Compared with the A340-300, the −500 features a 4.3-metre (14.1 ft) fuselage stretch, an enlarged wing, a significant increase in fuel capacity (around 50% larger than the −300), slightly higher cruising speed, a larger horizontal stabilizer and a larger vertical tailplane. The centerline main landing gear was changed to a four-wheel bogie to support the additional weight. The A340-500 is powered by four 240 kN (54,000 lbf) thrust Rolls-Royce Trent 553 turbofans and uses the Honeywell 331–600[A] APU.[119]

Designed for ultra long-haul routes, the −500 has a range of 9,000 nautical miles.[120] Due to its range, the −500 is capable of travelling non-stop from London to Perth, Western Australia, though a return flight requires a fuel stop due to headwinds.[121] Singapore Airlines used this model (initially in a two-class 181-passenger layout, later in a 100-passenger business-only layout) between early 2004 and late 2013 for its Newark–Singapore and Singapore–Newark nonstop routes SQ21 and SQ22. The former was an 18-hour, 45-minute 'westbound' (actually a polar route northbound to 130 km (70 nm) abeam the North Pole, then south across Russia, Mongolia and the People's Republic of China) and the latter was an 18-hour, 30-minute eastbound, 15,344 kilometres (8,285 nmi; 9,534 mi) journey. At the time, the flight was the longest scheduled non-stop commercial flight in the world.[87][122] Singapore Airlines even added a special compartment to the aircraft to store a corpse if a passenger were to die during the flight, though it was reported that its use had not been necessary.[123][122] Singapore Airlines suspended operating the flight from 2013 onwards partly due to high fuel prices at that time and returned its aircraft to Airbus in exchange for ordering new Airbus A350 aircraft.[122] The SQ21/SQ22 route was eventually resumed, flown by A350-900ULR aircraft.[124]

The A340-500IGW (Increased Gross Weight) version has a range of 17,000 km (9,200 nmi; 11,000 mi) and a MTOW of 380 t (840,000 lb) and first flew on 13 October 2006. It uses the strengthened structure and enlarged fuel capacity of the A340-600. The certification aircraft, a de-rated A340-541 model, became the first delivery, to Thai Airways International, on 11 April 2007.[125] Nigerian airline Arik Air received a pair of A340-542s in November 2008, using the type to immediately launch two new routes, Lagos–London Heathrow and Lagos–Johannesburg; a non-stop Lagos–New York route began in January 2010.[126][127] The A340-500IGW is powered by four 250 kN (56,000 lbf) thrust Rolls-Royce Trent 556 turbofans.

Like the A340-200, a shortened derivative of the −300, the −500 was unpopular.[128] This was primarily attributed to its perceived inefficiency, as it carried a relatively low number of passengers while still retaining most of the structural elements of its larger sibling, the A340-600, from which it was derived. Furthermore, operating in the specialized ultra long-haul market proved challenging, given the substantial fuel load required for such extended flights, making it a segment where profitability was hard to achieve.

As of August 2022, there are no longer any commercial A340-500 routes.[129] However, Azerbaijan Airlines later put both of its aircraft back in service later in 2022, but removed them from service as of January 2023.

A340-600

.jpg.webp)

Designed to replace early-generation Boeing 747-200/300 airliners, the A340-600 is capable of carrying 379 passengers in a three-class cabin layout for 13,900 km (7,500 nmi; 8,600 mi). It provides similar passenger capacity to a 747 but with 25 percent more cargo volume and with lower trip and seat costs. The first flight of the A340-600 was made on 23 April 2001.[130] Virgin Atlantic began commercial services in August 2002.[131][132] The variant's main competitor is the 777-300ER. The A340-600 was replaced by the A350-1000.

The A340-600 is 12 m (39 ft 4.4 in) longer than a −300, more than 4 m (13 ft 1.5 in) longer than the Boeing 747-400 and 2.3 m (7 ft 6.6 in) longer than the A380, and has two emergency exit doors added over the wings. It held the record for the world's longest commercial aircraft until the first flight of the Boeing 747-8 in February 2010. The A340-600 is powered by four 250 kN (56,000 lbf) thrust Rolls-Royce Trent 556 turbofans and uses the Honeywell 331–600[A] APU.[119] As with the −500, it has a four-wheel undercarriage bogie on the fuselage centre-line to cope with the increased MTOW along with the enlarged wing and rear empennage. Upper deck main cabin space can be optionally increased by locating facilities such as crew rest areas, galleys, and lavatories upon the aircraft's lower deck. In early 2007, Airbus reportedly advised carriers to reduce cargo in the forward section by 5.0 t (11,000 lb) to compensate for overweight first and business class sections; the additional weight caused the aircraft's centre of gravity to move forward thus reducing cruise efficiency. Affected airlines considered filing compensation claims with Airbus.[133]

The A340-600HGW (High Gross Weight) version first flew on 18 November 2005[134] and was certified on 14 April 2006.[135] It has an MTOW of 380 t (840,000 lb) and a range of up to 14,630 km (7,900 nmi; 9,090 mi), made possible by strengthened structure, increased fuel capacity, more powerful engines and new manufacturing techniques like laser beam welding. The A340-600HGW is powered by four 61,900 lbf (275 kN) thrust Rolls-Royce Trent 560 turbofans. Emirates became the launch customer for the −600HGW when it ordered 18 at the 2003 Paris Air Show;[136] but postponed its order indefinitely and later cancelled it. Rival Qatar Airways, which placed its order at the same airshow, took delivery of only four aircraft with the first aircraft on 11 September 2006.[137] The airline has since let its purchase options expire in favour of orders for the Boeing 777-300ER.[138]

As of July 2018, there were 60 A340-600s in service with six airlines worldwide.[118]

Operators

Over the duration of the programme, a total of 377 A340 family aircraft were delivered, of which 203 were in service as of March 2023. The largest scheduled airline operators were Lufthansa (34), Mahan Air (12), South African Airways (8), Swiss International Air Lines (5), and amongst other airlines, governments, charter and private operators with fewer aircraft of the type.[139]

Deliveries

| Deliveries | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Total | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 |

| A340-200 | 28 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 12 |

| A340-300 | 218 | - | - | - | - | 3 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 8 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 23 | 30 | 25 | 14 | 21 | 10 |

| A340-500 | 34 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| A340-600 | 97 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 18 | 15 | 14 | 16 | 8 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||

| A340 family | 377 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 10 | 12 | 14 | 25 | 28 | 26 | 28 | 16 | 22 | 19 | 20 | 24 | 33 | 28 | 19 | 25 | 22 |

'Note: The total number of deliveries corresponds to the Airbus O&D file,[2] while the details are given in the ABCD list..[140]

Accidents and incidents

The A340 has never been involved in a fatal accident, although there have been six hull losses:[141][142]

Accidents

- Landing phase

- 5 November 1997 – a Virgin Atlantic Flight 024 Airbus A340-311 conducted an emergency landing on Runway 27L at London Heathrow Airport with the aircraft's left-main landing gear partially extended. The aircraft was repaired and returned to service.[143][144]

- 29 August 1998 – a Sabena A340-200 (OO-SCW) was severely damaged while landing on Runway 25L at Brussels Airport. The right main gear collapsed; the right engines and wingtip hit the runway and slid to the right in soft ground. The 248 passengers and 11 crew were safely evacuated. The cause of the gear failure was found to be a fatigue crack. Although severely damaged, the aircraft was repaired and returned to service for 16 years until it was stored.[145]

- 2 August 2005 – Air France Flight 358 was destroyed by a crash and subsequent fire after it overran runway 24L at Toronto Pearson International Airport while landing in a thunderstorm. The aircraft slid into Etobicoke Creek and caught fire. All 297 passengers and 12 crew survived; 43 people were injured, 12 seriously.[146][147]

- 9 November 2007 – Iberia Airlines Flight 6463, an A340-600, was badly damaged after sliding off the runway at Ecuador's Mariscal Sucre International Airport. The landing gear collapsed and two engines broke off. All 345 passengers and 14 crew members were evacuated by inflatable slides, and there were no serious injuries. The aircraft was scrapped.[148]

- Take-off phase

- 20 March 2009 – Emirates Flight 407 was an Emirates flight flying from Melbourne to Dubai-International using an A340-500. The flight failed to take off properly from Melbourne Airport, hitting several structures at the end of the runway before eventually climbing enough to return to the airport for a safe landing. The occurrence was severe enough to be classified an accident by the Australian Transport Safety Bureau.[149][150] The plane was subsequently repaired, and returned to service for five years before it was scrapped.[151]

Incidents

- Fire related

- 20 January 1994 – an Air France A340-200 registered F-GNIA was destroyed by fire during servicing at Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport.[152] This marks the first hull-loss of an A340.

- 11 June 2018 – A Lufthansa A340-300, registration D-AIFA, was being towed with maintenance staff on board to the departure gate at Frankfurt's terminal when the tow truck caught fire. The flames substantially damaged the aircraft front section, and 10 people on the ground received minor injuries.[153] The damage was assessed to be beyond economical repair and the aircraft was written off.[151]

- Test related

- 15 November 2007 – an A340-600, A6-EHG, was damaged beyond repair during ground testing at Airbus' facilities at Toulouse Blagnac International Airport. During a pre-delivery engine test, some safety checks had been disabled,[154] leading to the unchocked aircraft accelerating to 31 knots (57 km/h; 36 mph) and colliding with a concrete blast deflection wall. The right wing, tail, and left engines made contact with the ground or wall, leaving the forward section elevated several metres and the cockpit broken off; nine people on board were injured, four of them seriously.[154][155] The aircraft was written off and was later used at Virgin Atlantic's cabin crew training facility in Crawley, England.[156] It had been due to be delivered to Etihad Airways.[157]

- War related

- 24 July 2001 – a SriLankan Airlines A340-300 registered 4R-ADD was destroyed on the ground at Bandaranaike International Airport; being one of 26 aircraft which were damaged or destroyed during a major attack upon the airport by Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam militants.[158][159]

Specifications

| Variant | A340-200[160] | A340-300[160] | A340-500[161] | A340-600[161] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew | Two | |||

| 3-class seats[162] | 210–250 | 250–290 | 270–310 | 320–370 |

| typ. layout | 303 (30F + 273Y) | 335 (30F + 305Y) | 313 (12F + 36J + 265Y) | 380 (12F + 54J + 314Y) |

| Exit limit[163] | 420[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4]/375[lower-alpha 5] | 375[lower-alpha 5]/440[lower-alpha 3][lower-alpha 4] | 375[lower-alpha 5] | 440[lower-alpha 5] |

| Length[162] | 59.4 m / 195 ft 0 in | 63.69 m / 208 ft 11 in | 67.93 m / 220 ft 10 in | 75.36 m / 247 ft 3 in |

| Wingspan | 60.3 m (197.83 ft) | 63.45 m (208.17 ft) | ||

| Wing[164] | 363.1 m2 (3,908 sq ft), 29.7° sweep, 10 AR | 437.3 m2 (4,707 sq ft), 31.1° sweep, 9.2 AR | ||

| Height | 17.03 m (55.86 ft) | 16.99 m (55.72 ft) | 17.53 m (57.51 ft) | 17.93 m (58.84 ft) |

| Fuselage | 5.287 m (208.15 in) cabin width, 5.64 m (18.5 ft) outside width | |||

| Cargo volume | 132.4 m3 (4,680 cu ft) | 158.4 m3 (5,590 cu ft) | 149.7 m3 (5,290 cu ft) | 201.7 m3 (7,120 cu ft) |

| MTOW | 275 t (606,000 lb) | 276.5 t (610,000 lb) | 380 t (840,000 lb) | |

| Max. PL | 51 t (112,000 lb) | 52 t (115,000 lb) | 54 t (119,000 lb) | 66 t (146,000 lb) |

| OEW | 118 t (260,000 lb) | 131 t (289,000 lb) | 168 t (370,000 lb) | 174 t (384,000 lb) |

| Max. Fuel | 110.4 t (243,395 lb) | 175.2 t (386,292 lb) | 155.5 t (342,905 lb)[lower-alpha 6] | |

| Engines (×4) | CFM International CFM56-5C | Trent 553 | Trent 556 | |

| Thrust (×4)[163] | 138.78–151.24 kN (31,200–34,000 lbf) | 248.12–275.35 kN (55,780–61,902 lbf) | ||

| Speed | Max.: Mach 0.86 (493 kn; 914 km/h; 568 mph) at 12,000 m (39,000 ft)[162] Cruise: Mach 0.82 (470 kn; 871 km/h; 541 mph) at 12,000 m (39,000 ft) | |||

| Range, 3-class[162] | 12,400 km (6,700 nmi; 7,700 mi) | 13,500 km (7,300 nmi; 8,400 mi) | 16,670 km (9,000 nmi; 10,360 mi) | 14,450 km (7,800 nmi; 8,980 mi) |

| Take off[lower-alpha 7] | 2,900 m (9,500 ft) | 3,000 m (10,000 ft) | 3,350 m (10,990 ft) | 3,400 m (11,200 ft) |

| Ceiling[163] | 12,527 m (41,100 ft) | 12,634 m (41,450 ft) | ||

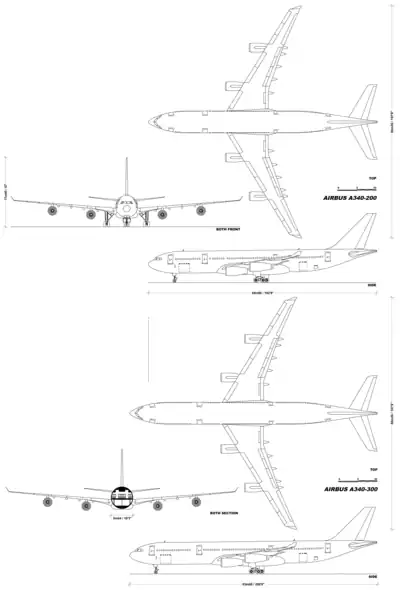

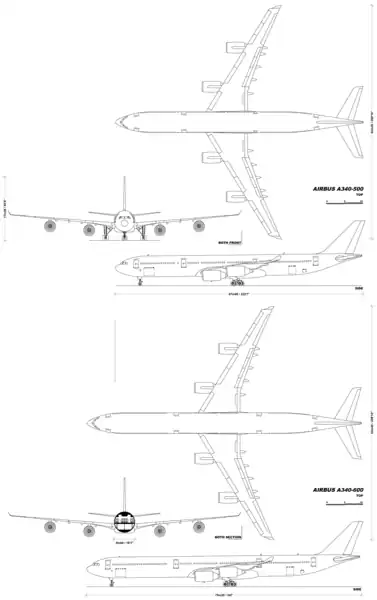

- Line drawings

A340-200/300

A340-200/300 A340-500/600

A340-500/600

Engines

| Model | Certification date | Engines[163] |

|---|---|---|

| A340-211 | 22 December 1992 | CFM 56-5C2 |

| A340-212 | 14 March 1994 | CFM 56-5C3 |

| A340-213 | 19 December 1995 | CFM 56-5C4 |

| A340-311 | 22 December 1992 | CFM 56-5C2 |

| A340-312 | 14 March 1994 | CFM 56-5C3 |

| A340-313 | 16 March 1995 | CFM 56-5C4 |

| A340-541 | 3 December 2002 | RR Trent 553-61 / 553A2-61 |

| A340-542 | 15 February 2007 | RR Trent 556A2-61 |

| A340-642 | 21 May 2002 | RR Trent 556-61 / 556A2-61 |

| A340-643 | 11 April 2006 | RR Trent 560A2-61 |

See also

- Competition between Airbus and Boeing

- Deli Mike, an A340-300 that has strange unreliability

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

- Notes

- The higher the aspect ratio, the greater the aerodynamic efficiency: A higher aspect ratio wing has a lower drag and a slightly higher lift than a lower aspect ratio wing.[72]

- This is the thickness to chord ratio of the early Airbus A340 variants, which share the same wing with the A330

- 4 Type A doors

- 9-abreast

- 8-abreast

- no aux. tank, 164 t (361,595 lb) with 1 aux. tank

- MTOW, SL, ISA

- References

- "Completion of production marks new chapter in the A340 success story" (Press release). Airbus. 10 November 2011.

- "Airbus orders and deliveries". Airbus. 31 July 2017. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- Wensveen 2007, p. 63.

- Gunston 2009, p. .

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 18.

- Eden 2008, p. 30

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 23.

- Norris & Wagner 1999, p. 59.

- Maynard, Micheline (11 June 2008). "To Save Fuel, Airlines Find No Speck Too Small". The New York Times.

- "Commercial Aircraft of the World part 2". Flight International. 17 October 1981. Retrieved 23 January 2011.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 22.

- Kingsley-Jones, Max (4 November 1997). "Airbus A330/A340". Flight International. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, pp. 22–23.

- Norris & Wagner 1999, p. 24.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 27.

- Lawrence & Thornton 2005, p. 73.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 24.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 26.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 28.

- Norris & Wagner 1999, p. 67.

- Gunston 2009, p. 201.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 36.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 51.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 52.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 53.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 32.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 55.

- "Timeline 40 Years of Innovation" (PDF). Airbus. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- "Long time coming". Flight International. 12 June 2001.

- Norris & Wagner 1999, p. 66.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 59.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 65.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 67.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 71.

- David M. North (13 July 1992). "A340 Handling, Cockpit Design Improve on Predecessor A320". Aviation Week & Space Technology.

- Eden 2008, p. 35.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 72.

- "World ranger" (Press release). Airbus. 16 June 1993. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, pp. 73–74.

- Eden 2008, pp. 29, 37.

- "Boeing 777 Distance and Speed World Records Confirmed" (Press release). Boeing. 29 July 1997.

- Brian Bostick (24 September 2012). "The A340-400X?". Aviation Week Network.

- "New engine for stretched A340". Flight International. 6 November 1991.

- Kieran Daly (15 June 1994). "Airbus selects A3XX concept and works to fill gaps in product line". Flight International.

- "Airliners of the world". Flight International. 6 December 1995.

- Julian Moxon (24 April 1996). "GE/Airbus sign for A340-600". Flight International.

- Max Kingsley-Jones; Guy Norris (28 August 1996). "X-tended players". Flight Global.

- David Learmount (9 October 1996). "Airbus pushes on with new versions of A340". Flight International.

- "Airliners of the world". Flight International. 4 December 1996.

- Andrew Doyle (25 February 1997). "Airbus suffers setback as GE walks away from A340-600". Flight International.

- Julian Moxon (18 June 1997). "Airbus makes Trent 500 deal with Rolls-Royce". Flight International.

- Max Kingsley-Jones and Kevin O'Toole (17 December 1997). "Airbus board gives the goahead for A340 offspring". Flight International.

- Max Kingsley-Jones (2 September 1998). "Have four engines, will travel far". Flight International.

- "Enhanced A340 to take on 777". Flight International. 29 November 2005.

- Flottau, Jens. "Airbus Bids Adieu to A340, Postpones A350 Delivery." Archived 14 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Week & Space Technology, 14 November 2011.

- Andrea Rothman (10 November 2011). "Airbus's Longest Plane Proves Short-Lived as A340 Orders Dry Up". Bloomberg.

- "A340-600 Values Represent Disaster for Owners". Aircraft Value News. 20 August 2018.

- "A340-300 & B777-200ER Current & Residual Values 'On Watch' Status". Aviation Today. 23 January 2006. Archived from the original on 29 April 2015.

- "Airbus A340". Aviation Week & Space Technology. 29 October 2007. p. 63.

- "Airbus aircraft 2011 average list prices" (PDF). Airbus. January 2011.

- "Airbus Delays A350-900, Terminates A340." Archived 21 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Week, 10 November 2011. "The company also announced that it is terminating the A340 program, which has not seen any sales recently. All of the 246 Airbus A340-200s and −300s are delivered. Airbus lists 133 orders and 129 deliveries for the A340-500/600 program."

- Compart, Andrew. "Young at Part". Aviation Week and Space Technology, 15 April 2013. pp. 44–46.

- "Haunted by old pledges, Airbus aims to boost A340 value". Reuters. 5 December 2013. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- "Airbus, engine OEMs make the case for A340 future – Leeham News and Comment". Leeham. 9 December 2013.

- "Weight in waiting." Aviation Week and Space Technology, 14 April 2014. pp. 54–55.

- "Corporate Jets > ACJ340". Airbus. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Obert 2009, p. 261.

- de Montalk, J.P. Potocki (2001). "New Avionics Systems — Airbus A330/A340" (PDF). CRC Press LLC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2016.

- Obert 2009, pp. 261, 448.

- Gunston 2009, p. 188.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, pp. 50–51.

- "Wing Geometry Definitions". NASA. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 50.

- "A330-300 Dimensions & key data". Airbus S.A.S. Retrieved 20 November 2012.

- Simona Ciornei (31 May 2005). "Mach number, relative thickness, sweep and lift coefficient of the wing – An empirical investigation of parameters and equations" (PDF). Hamburg University of Applied Sciences.

- Gunston 2009, p. 195.

- "Aircraft Data File". Civil Jet Aircraft Design. Elsevier. July 1999.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. 31.

- Gunston 2009, p. 197.

- "Airbus A330 Wide-Bodied Medium/Long-Range Twin-Engine Airliner, Europe". Aerospace-technology.com. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- "A330 Flight deck and systems briefing for pilots" (PDF). Airbus S.A.S. March 1999. p. 173. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- Dubois, Thierry. "Airbus A340: Smart Design." Archived 13 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Today, 1 June 2003.

- Eden 2008, p. 36.

- "A brief history of Virgin Atlantic." Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Virgin Atlantic, Retrieved: 11 May 2014.

- Zuckerman, Laurence (1 July 1999). "Boeing and Airbus Battle Over Singapore Airline Sales". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- "Singapore Airlines A340-500 Flies Into The Record Books". Archived 22 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine Airbus S.A.S, 4 February 2004.

- "Singapore Air makes longest flight". CNN. Archived from the original on 25 December 2007.

- Peterson, Barbara (24 October 2012). "Singapore Airlines to End World's Longest Flight". The Daily Traveler. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014.

- Doganis 2002, pp. 133–135.

- Lombardo, David A. "Airbus unveils A340-200 bizliner." Archived 14 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine Aviation International News, 27 May 2008.

- "Bundeswehr will im Eiltempo neue Regierungsflugzeuge anschaffen". Der Spiegel. 7 March 2008. Retrieved 12 March 2008.

- Osborne, Tony. "French Air Force A400M Breaks Cover." Archived 14 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Week, 17 January 2013.

- "Picture: Former Sultan of Brunei's unique A340-8000 derivative destined for Saudi Arabian VIP after nine years storage". Flight International. 7 March 2007. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

- Whyte, Alasdair. "Selling a VIP business jet to Colonel Gaddafi." Archived 16 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine corporatejetinvestor.com, 16 August 2013.

- Michaels, Daniel. "Airlines Cut Long Flights To Save Fuel Costs." Archived 28 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Wall Street Journal, 8 July 2008.

- Airlines curb Long Flights to Save on Fuel, The Wall Street Journal, 8 July 2008, pp. B1-B2.

- "Cathay Pacific To Cut Flights To Los Angeles". The Wall Street Journal. 12 August 2008. Retrieved 4 September 2023.

- Broderick, Sean. "A340 Operators Spend On Interiors, Engines." Archived 14 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Week, 23 September 2013. "...Technology, particularly in twinjet airframe and engine design, simply got better. And it doomed almost all quad jets—and certainly those battling twins of comparable capacity—in the process."

- Carol Matlack. "Airbus's A340 Resale Value Guarantee Could Cost Billions – Businessweek". Businessweek.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Carol Matlack. "Airbus's A340 Resale Value Guarantee Could Cost Billions – Businessweek". Businessweek.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Kingsley-Jones, Max. "Emirates begins parting out its A340-500s". Flightglobal. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

- Haria, Rupa. "Weight in Waiting." Aviation Week and Space Technology, 14 April 2014. pp. 54–55.

- Gubisch, Michael (2 January 2014). "Snecma to flight-test open rotor on A340 in 2019". Flight International. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

- Warwick, Graham (19 June 2013). "Snecma Prepares For Crucial Open-rotor Tests". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

- aero.de (German) 21 January 2021

- "Lufthansa to Remove 5 Airbus A340-600s from Desert Storage". simpleflying.com. 25 June 2021.

- "A New Coat of Paint Shows Lufthansa's Commitment to the A340". 16 February 2021.

- "Lufthansa Doesn't Intend to Resume Airbus A340-600 Flights". 22 January 2021.

- Spalding, Katie (26 November 2021). "Airbus 340 Plane Lands In Antarctica For First Time In History". IFL Science. Archived from the original on 27 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- "A340 Family: Versatility on long-range and ultra-long-range flights". Airbus. 16 January 2022.

- "ASN Aviation Safety Database - A340". Aviation Safety Network. 11 July 2023. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- "ICAO Document 8643". International Civil Aviation Organization. Archived from the original on 30 August 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2011.

- "A330/A340 family: Twin-and four-engine efficiency". Airbus. Archived from the original on 19 November 2010. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- "Product Catalog". Honeywell. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- "Conviasa to End World's Last A340-200 Passenger Service". Airwaysmag.com. Retrieved 20 October 2022.

- "The Market for Large Commercial Jet Transports 2011–2020" Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Forecast International, July 2011.

- "Boeing: 777 way much better than A330". 8 December 2010.

- "World Airline Census 2018". Flightglobal.com. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- "Product Catalog". Honeywell. Archived from the original on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 18 November 2010.

- "A340-500 Specifications". Airbus. Archived from the original on 22 January 2011.

- Clark, Andrew (29 June 2004). "Record longest flight flies in the face of its critics". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- Bachman, Justin (21 October 2013). "The End of the World's Longest Nonstop Flights". Bloomberg. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Andrew Clark (11 May 2004). "Airline's new fleet includes a cupboard for corpses". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 May 2012.

- "Singapore Airlines To Launch World's Longest Commercial Flights". Singapore Airlines. Singapore Airlines.

- Jetphotos Airbus A340-541HGW HS-TLD Archived 19 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine JetPhotos.net

- Kingfisher Purchases Five Airbus A340-500 Archived 12 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine flykingfisher.com

- "Kingfisher grows its Airbus fleet with purchase of five A340-500" (Press release). Airbus. 24 April 2006. Archived from the original on 3 December 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- "Airbus, engine OEMs make the case for A340 future – Leeham News and Comment". 8 December 2013.

- James Pearson (7 October 2021). "All Gone: There Are No More Airline Airbus A340-500 Flights". Simpleflying.

- Norris & Wagner 2001, p. .

- "VIRGIN ATLANTIC'S A340-600 – THE LONGEST PLANE IN THE WORLD – TAKES ITS FIRST COMMERCIAL FLIGHT". Asiatraveltips.com. 1 August 2002. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- "Virgin Atlantic's A340-600 – the Longest Plane in the World – Takes its First Commercial Flight" (Press release). 5 August 2002. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2010 – via Pressreleasenetwork.com.

- Robertson, David (7 April 2007). "Carriers ponder compensation claims against Airbus for overweight aircraft". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 8 April 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- "New A340-600 takes to the skies". 18 November 2005. Archived from the original on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2006.

- "Newly certified A340-600 brings 18% higher productivity". 14 April 2006. Archived from the original on 16 June 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2006.

- "Emirates orders 41 additional Airbus aircraft". 16 June 2003. Archived from the original on 19 May 2006. Retrieved 6 August 2006.

- "Qatar Airways First Airbus A340-600 Arrives in Doha". www.qatarairways.com

- Wallace, James; Aerospace, P-I (29 November 2007). "First Boeing jet of many touches down in Qatar". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved 2 July 2011.

- "Orders & Deliveries". Airbus. 31 March 2023. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 12 April 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Airbus Production List A330, A340". ABCDlist. 16 January 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- "Airbus A340 Hull Losses". aviation-safety.net. Flight Safety Foundation. Retrieved 10 April 2014.

- Ranter, Harro. "Airbus A340 database". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- FSF Editorial Staff. "A340 Crew Conducts Emergency Landing With Left-main Gear Partially Extended" (PDF). flightsafety.org. Retrieved 15 December 2017.

- Accident description for Airbus A340-311 G-VSKY at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 25 September 2019.

- "Royal Jordanian Airlines JY-AIC (Airbus A340 – MSN 14) (Ex F-GNIB F-OHLP OO-SCW ) | Airfleets aviation". www.airfleets.net. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Accident description for Airbus A340-313X F-GLZQ at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 10 April 2014.

- "TSB advises runway changes in light of Air France crash." Archived 13 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine CBC News, 12 December 2007.

- Accident description for Airbus A340-642 EC-JOH at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 10 April 2014.

- Stewart, Cameron (12 September 2009). "The devil is in the data". The Australian. Retrieved 26 January 2011.

- Whinnett, Ellen (12 July 2009). "Emirates pilot in tail strike near-disaster tells his story". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 31 December 2012.

- Accident description for Airbus A340-313 D-AIFA at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 25 September 2019.

- Accident description for Airbus A340-211 F-GNIA at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 10 April 2014.

- "Lufthansa A340 Damaged as Frankfurt Airport Truck Catches Fire". Bloomberg.com. 11 June 2018.

- "Accident survenu le 15 novembre 2007 sur l'aérodrome de Toulouse Blagnac à l'Airbus A340-600 numéro de série 856" [Accident occurred on November 15, 2007 on the Toulouse Blagnac aerodrome on the Airbus A340-600 serial number 856] (PDF) (in French). Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety. ISBN 978-2-11-098259-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 November 2009. Retrieved 4 November 2009.

- Kaminski-Morrow, David (10 December 2008). "Violation of test procedures led to Toulouse A340-600 crash". Flightglobal. Reed Business Information. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013.

- "Toulouse accident occurred as Airbus A340 was exiting engine test-pen". Flight International. Archived from the original on 11 December 2008. Retrieved 17 November 2008.

- Accident description for Airbus A340-642 F-WWCJ at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 25 September 2019.

- Accident description for Airbus A340-312 4R-ADD at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 10 April 2014.

- "Intelligence failures exposed by Tamil Tiger airport attack". Jane's Intelligence Review. 2001. Archived from the original on 25 February 2008.

- "Aircraft Characteristics Airport Planning – A340-200/300" (PDF). Airbus. July 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2021.

- "Aircraft Characteristics Airport Planning – A340-500/600" (PDF). Airbus. July 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 November 2021.

- "A340-200". 16 June 2021., "A340-300". 16 June 2021., "A340-500". 16 June 2021., "A340-600". Airbus. 16 June 2021.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet A.015 AIRBUS A340 Issue 20" (PDF). European Aviation Safety Agency. 21 October 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- "Airbus Aircraft Data File". Civil Jet Aircraft Design. Elsevier. July 1999.

- Bibliography

- Doganis, Rigas (2002). Flying Off Course: The Economics of International Airlines. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4152-1323-3.

- Eden, Paul E., ed. (2008). Civil Aircraft Today. London: Amber Books. ISBN 978-1-905704-86-6.

- Gunston, Bill (2009). Airbus: The Complete Story. Sparkford, Yeovil, Somerset, UK: Haynes Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84425-585-6.

- Lawrence, Phillip K.; Thornton, David Weldon (2005). Deep Stall: The Turbulent Story of Boeing Commercial Airplanes. London: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-4626-6.

- Norris, Guy; Wagner, Mark (2001). Airbus A340 and A330. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing. ISBN 0-7603-0889-6.

- Norris, Guy; Wagner, Mark (1999). Airbus. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing. ISBN 0-7603-0677-X.

- Obert, Ed (2009). Aerodynamic Design of Transport Aircraft. IOS Press. ISBN 978-1-6075-0407-8.

- Wensveen, J.G. (2007). Air Transportation: A Management Perspective. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-7171-8.

External links

- Official Airbus A330 and A340 airliners web page

- Airbus A340-200/300 page on airliners.net

- Airbus A340 production list

- "Airbus A340 Report". Forecast International. April 2007.

_and_VH-ZPL_'Samba_Blue'_Embraer_190-100IGW_Virgin_Blue_(Virgin_Australia)_(6600549415).jpg.webp)