Al-Muntasir

Abu Ja'far Muhammad (Arabic: أبو جعفر محمد; November 837 – 7 June 862), better known by his regnal title al-Muntasir bi-llah (المنتصر بالله, "He who triumphs in God") was the caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate from 861 to 862, during the "Anarchy at Samarra".

| al-Muntasir bi-llah المنتصر بالله | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caliph Commander of the Faithful | |||||

| |||||

| 11th Caliph of the Abbasid Caliphate | |||||

| Reign | 11 December 861 – 7 June 862 | ||||

| Predecessor | al-Mutawakkil | ||||

| Successor | al-Musta'in | ||||

| Born | November 837 Samarra, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||

| Died | 7 June 862 (aged 24) Samarra, Abbasid Caliphate | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Issue | Ja'far | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Abbasid | ||||

| Father | al-Mutawakkil | ||||

| Mother | Hubshiya | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Early life

Al-Muntasir was the eldest son of Abu al-Fadl Ja'far (future Abbasid caliph al-Mutawakkil). At the time of his birth, his father was fourteen years old. His given name was Muhammad. Al-Muntasir's mother was Hubshiya, a Greek slave.[1]

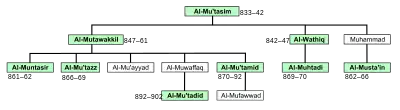

In 849, al-Mutawakkil arranged for his succession, by appointing three of his sons as heirs and assigning them the governance and proceeds of the Empire's provinces: the eldest, al-Muntasir, was named first heir, and received the governorship of Egypt, the Jazira, and the proceeds of the rents in the capital, Samarra; al-Mu'tazz was charged with supervising the domains of the governor in the Khorasan; and al-Mu'ayyad was placed in charge of Syria.[2]

Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari records that in 236 AH (850–851) al-Muntasir led a pilgrimage. The previous year al-Mutawakkil had named his three sons as heirs and seemed to favor al-Muntasir. However, afterward, this seemed to change and al-Muntasir feared his father was going to move against him. So, he decided to strike first. Al-Mutawakkil was killed by a Turkish soldier on Wednesday 10 December 861.

Involvement in the assassination of al-Mutawakkil

Al-Mutawakkil had appointed his oldest son, al-Muntasir, as his heir in 849/50, but slowly had shifted his favor to his second son, al-Mu'tazz, encouraged by al-Fath ibn Khaqan and the vizier Ubayd Allah ibn Yahya ibn Khaqan. This rivalry extended into the political sphere, as al-Mu'tazz's succession appears to have been backed by the traditional Abbasid elites as well, while al-Muntasir was backed by the Turkic and Maghariba guard troops.[3][4] In late autumn 861, matters came to a head: in October, al-Mutawakkil ordered the estates of the Turkic general Wasif to be confiscated and handed over to al-Fath. Feeling backed into a corner, the Turkic leadership began a plot to assassinate the Caliph.[5][6] They were soon joined, or at least had the tacit approval, of al-Muntasir, who smarted from a succession of humiliations: on 5 December, on the recommendation of al-Fath and Ubayd Allah, he was bypassed in favor of al-Mu'tazz for leading the Friday prayer at the end of Ramadan, while three days later, when al-Mutawakkil was feeling ill and chose al-Muntasir to represent him on the prayer, once again Ubayd Allah intervened and persuaded the Caliph to go in person. Even worse, according to the historian al-Tabari, on the next day, al-Mutawakkil alternately vilified and threatened to kill his eldest son, and even had al-Fath slap him on the face. With rumors circulating that Wasif and the other Turkish leaders would be rounded up and executed on 12 December, the conspirators decided to act.[4][7]

According to al-Tabari, a story later circulated that al-Fath and Ubayd Allah were forewarned of the plot by a Turkic woman, but had disregarded it, confident that no one would dare carry it out.[8][9] On the night of 10/11 December, about one hour after midnight, the Turks burst in the chamber where the caliph and al-Fath were having supper. Al-Fath was killed trying to protect the Caliph, who was killed next. Al-Muntasir, who now assumed the caliphate, initially claimed that al-Fath had murdered his father and that he had been killed after; within a short time, however, the official story changed to al-Mutawakkil choking on his drink.[10][11]

Reign

On the same day as the assassination, al-Muntasir succeeded smoothly to the throne of the Caliphate with the support of the Turkic faction. The Turkic party then prevailed on al-Muntasir to remove his brothers from the succession, fearing they would seek revenge for his involvement in the murder of their father. In their place, he was to appoint his son as heir apparent. On 27 April 862, both brothers wrote statements of abdication, although al-Mu'tazz did so after some hesitation.

Al-Muntasir became caliph on December 11, 861, after his father al-Mutawakkil was assassinated by members of his Turkic guard.[12] Although he was suspected of being involved in the plot to kill al-Mutawakkil, he was able to quickly take control of affairs in the capital city of Samarra and receive the oath of allegiance from the leading men of the state.[13] Al-Muntasir's sudden elevation to the Caliphate served to benefit several of his close associates, who gained senior positions in the government after his ascension. Included among these were his secretary, Ahmad ibn al-Khasib, who became vizier, and Wasif, a senior Turkic general who had likely been heavily involved in al-Mutawakkil's murder.[14]

Al-Muntasir was lauded because, unlike his father, he loved the house of ʻAlī (Shīʻa) and removed the ban on pilgrimage to the tombs of Hassan and Hussayn. He sent Wasif to raid the Byzantines.

War with Byzantines

Shortly after securing his position as caliph, al-Muntasir decided to send an Abbasid army against the Byzantines. According to al-Tabari, this decision was prompted by Ahmad ibn al-Khasib; the vizier had recently had a falling out with Wasif, and he sought to find an excuse to get him out of the capital. Ahmad ultimately decided that the best way to accomplish this was to put him at the head of a military campaign. He was eventually able to convince the caliph to go along with the plan, and al-Muntasir ordered Wasif to head to the Byzantine frontier.[15]

Having completed their preparations for the campaign, Wasif and the army departed for the Byzantine frontier in early 862. Upon arriving at the Syrian side of the frontier zone,[16] They set up camp there in preparation for their incursions into Byzantine territory.[17]

Before Wasif had a chance to make any serious progress against the Byzantines, however, the campaign was overshadowed by events back at the capital. After a reign of only six months, al-Muntasir died around the beginning of June, of either illness or poison. Following his death, the vizir Ahmad ibn al-Khasib and a small group of senior Turkish commanders met and decided to appoint al-Musta'in as caliph in his stead. They presented their decision to the Samarran military regiments and were eventually able to force the soldiers to swear allegiance to their candidate.[18]

The death of al-Muntasir did not immediately result in the termination of the military campaign. Wasif, upon learning of the passing of the caliph, decided that he should still persist with the operation, and led his forces into Byzantine territory. The army advanced against a Byzantine fortress called Faruriyyah[19] in the region of Tarsus.[20] The defenders of the fortress were defeated and the stronghold was conquered by the Muslims.[17]

Ultimately, however, the change of government in Samarra brought the expedition to a premature conclusion. The ascension of al-Musta'in could not be ignored indefinitely by Wasif; having already missed the opportunity to play a role in the selection of the new caliph, he needed to make sure his interests back in the capital were protected. As a result, he decided to abandon the Byzantine front, and by 863 he was back in Samarra.[21]

Death

Al-Muntasir's reign lasted less than half a year; it ended with his death from unknown causes on Sunday, 7 June 862, at the age of 24 years (solar). There are various accounts of the illness that led to his death, including that he was bled with a poisoned lancet. Al-Tabari (p. 222-3) states that al-Muntasir is the first Abbasid whose tomb is known, that it was made public by his mother, a Greek slave girl, and that earlier caliphs desired their tombs to be kept secret for fear of desecration. Joel L. Kraemer in his translation of al-Tabari notes on page 223:

"'Ayni comments, citing al-Sibt (b. al-Jawzi), that Tabari's statement here is surprising since the tombs of the Abbasid caliphs are in fact known, e.g., the tomb of al-Saffah is in Anbar beneath the minbar; and those of al-Mahdi in Masabadhan, Harun in Tus, al-Ma'mun in Tarsis, and al-Mu'tasim, al-Wathiq and al-Mu'tawakkil in Samarra."

Succession

His father, caliph al-Mutawakkil (r. 847–861) had created a plan of succession that would allow his sons to inherit the caliphate after his death; he would be succeeded first by his eldest son, al-Muntasir, then by al-Mu'tazz and third by al-Mu'ayyad.[22] During al-Muntasir's short reign (r. 861–862), the Turks convinced him into removing al-Mu'tazz and al-Mu'ayyad from the succession. When al-Muntasir died, the Turkic officers gathered together and decided to install the dead caliph's cousin Ahmad al-Musta'in on the throne.[23]

See also

- al-Muhtadi, cousin of al-Muntasir

- al-Mu'tamid, brother of al-Muntasir

- al-Muwaffaq, brother of al-Muntasir

- Ahmad ibn al-Khasib al-Jarjara'i, vizier of al-Muntasir

References

- Kennedy 2006, p. 173.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 167.

- Gordon 2001, p. 82.

- Kennedy 2004, p. 169.

- Kraemer 1989, p. 171.

- Kennedy 2004, pp. 168–169.

- Kraemer 1989, pp. 171–173, 176.

- Kraemer 1989, pp. xx, 181.

- Kennedy 2006, p. 265.

- Kraemer 1989, pp. 171–182, 184, 195.

- Kennedy 2006, pp. 264–267.

- Bosworth, "al-Muntasir," p. 583

- Kennedy, 266-68

- Gordon, pp. 88-91

- Al-Tabari, v. 34: p. 204; Ibn al-Athir, p. 111. Al-Mas'udi, p. 300, states that al-Muntasir ordered the campaign to disperse the Turkish army and remove them from Samarra.

- "Thughūr al-Shāmiyyah," the Syrian frontier. The thughūr or forward frontier zone stretched along the northern regions of both Syria and the Jazira; Bonner, p. 17

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: pp. 7-8; Ibn al-Athir, p. 119

- Gordon, p. 90; al-Tabari, v. 35: pp. 1-5

- Al-Tabari, v. 35: pp. 7-8. Bosworth, "The City of Tarsus," p. 274, refers to F.rūriyya as being "dubiously identifiable."

- Al-Mas'udi; p. 300

- Gordon, pp. 91, 220 n. 189; al-Tabari, v. 35: p. 11

- Bosworth, "Mu'tazz," p. 793

- Bosworth, "Muntasir," p. 583

Bibliography

- Kennedy, Hugh (2004). The Prophet and the Age of the Caliphates: The Islamic Near East from the 6th to the 11th Century (Second ed.). Harlow: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-40525-7.

- Kennedy, Hugh (2006). When Baghdad Ruled the Muslim World: The Rise and Fall of Islam's Greatest Dynasty. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306814808.

- Kraemer, Joel L., ed. (1989). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume XXXIV: Incipient Decline: The Caliphates of al-Wāthiq, al-Mutawakkil and al-Muntaṣir, A.D. 841–863/A.H. 227–248. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-874-4.

- Gordon, Matthew S. (2001). The Breaking of a Thousand Swords: A History of the Turkish Military of Samarra (A.H. 200–275/815–889 C.E.). Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-4795-2.

- Masudi (28 October 2013). Meadows Of Gold. Routledge Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-14522-3.

- William Muir, The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline, and Fall.