Alben W. Barkley

Alben William Barkley (/ˈbɑːrkli/; November 24, 1877 – April 30, 1956) was an American lawyer and politician from Kentucky who served as the 35th vice president of the United States from 1949 to 1953 under President Harry S. Truman. In 1905, he was elected to local offices and in 1912 as a U.S. representative. Serving in both houses of Congress, he was a liberal Democrat, supporting President Woodrow Wilson's New Freedom domestic agenda and foreign policy.[1]

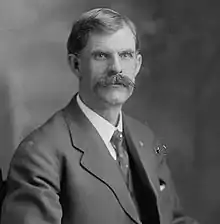

Alben W. Barkley | |

|---|---|

Official portrait, 1949 | |

| 35th Vice President of the United States | |

| In office January 20, 1949 – January 20, 1953 | |

| President | Harry S. Truman |

| Preceded by | Harry S. Truman |

| Succeeded by | Richard Nixon |

| Senate Majority Leader | |

| In office July 14, 1937 – January 3, 1947 | |

| Deputy | J. Lister Hill Sherman Minton J. Hamilton Lewis |

| Preceded by | Joseph Taylor Robinson |

| Succeeded by | Wallace H. White |

| Senate Minority Leader | |

| In office January 3, 1947 – January 3, 1949 | |

| Deputy | Scott W. Lucas |

| Preceded by | Wallace H. White |

| Succeeded by | Kenneth S. Wherry |

| Chair of the Senate Democratic Caucus | |

| In office July 14, 1937 – January 3, 1949 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Taylor Robinson |

| Succeeded by | Scott W. Lucas |

| United States Senator from Kentucky | |

| In office January 3, 1955 – April 30, 1956 | |

| Preceded by | John Sherman Cooper |

| Succeeded by | Robert Humphreys |

| In office March 4, 1927 – January 19, 1949 | |

| Preceded by | Richard P. Ernst |

| Succeeded by | Garrett L. Withers |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Kentucky's 1st district | |

| In office March 4, 1913 – March 3, 1927 | |

| Preceded by | Ollie M. James |

| Succeeded by | William Voris Gregory |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Willie Alben Barkley November 24, 1877 Lowes, Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | April 30, 1956 (aged 78) Lexington, Virginia, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Kenton Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 3 |

| Relatives | Stephen M. Truitt (grandson) |

| Education | Marvin College (BA) |

| Signature | |

Endorsing Prohibition and denouncing parimutuel betting, Barkley narrowly lost the Kentucky Democratic gubernatorial primary in 1923 to fellow representative J. Campbell Cantrill. In 1926, he unseated Republican senator Richard P. Ernst. In the Senate, he supported the New Deal approach to handling the Great Depression in the United States. Democrats chose him to succeed Senate Majority Leader Joseph Taylor Robinson upon Robinson's death in 1937. His 1938 re-election bid was an intense, bitter victory against Governor A. B. "Happy" Chandler.[2] When World War II focused President Franklin D. Roosevelt's attention on foreign affairs, Barkley gained influence over the administration's domestic agenda. He resigned as floor leader after Roosevelt ignored his advice and vetoed the Revenue Act of 1943.[3] The veto was overridden by both houses and the Democratic senators unanimously re-elected Barkley to the position of Majority Leader.

Barkley had a good working relationship with Senator Harry S. Truman, who became vice-president and then president in 1945. With Truman's popularity waning entering the 1948 Democratic National Convention, Barkley gave a keynote address that energized the delegates. Truman selected him as his running mate for the upcoming election, and the Democratic ticket scored an upset victory against Thomas Dewey and Earl Warren of the Republican Party. Barkley took an active role in the Truman administration, acting as its primary spokesman, especially after the Korean War required the majority of Truman's attention. When Truman announced that he would not seek re-election in 1952, Barkley began organizing a presidential campaign, but labor leaders refused to endorse his candidacy because of his age, and he withdrew from the race. He is the last vice president from the Democratic Party to never receive the party nomination for president. He retired but was coaxed back into public life, defeating incumbent Republican senator John Sherman Cooper in 1954.[4] Barkley died of a heart attack on April 30, 1956.[5]

Early life and education

Willie Alben Barkley, the eldest of eight children of John Wilson Barkley (1854–1932) and Electa Eliza (Smith) Barkley (1858–1945), was born November 24, 1877.[6][7] His grandmother, midwife Amanda Barkley, delivered him in the log house she lived in with her husband, Alben, in Wheel, Kentucky.[8] Barkley's parents were tenant farmers who grew tobacco, and his father was an elder in the local Presbyterian church.[9] Barkley traced his father's ancestry to Scots-Irish Presbyterians in Rowan County, North Carolina.[10] Both parents were religious, opposed to playing cards and alcohol.[9] Occasionally, Barkley's parents would leave him in the care of his grandparents for extended periods.[11] During these times, his grandmother related stories of her relatives. Her childhood playmates included future U.S. Vice President Adlai Stevenson I and James A. McKenzie, a future U.S. representative from Kentucky.[11]

Barkley worked on his parents' farm and attended school in Lowes, Kentucky, between the fall harvest and spring planting.[12] Unhappy with his birth name, he adopted "Alben William" as soon as he was old enough to express his opinion in the matter.[13] In the difficult economy of late 1891, relatives convinced Barkley's father to sell his farm and move to Clinton, to pursue opportunities as a tenant wheat farmer.[14] Barkley enrolled at a local seminary school, but did not finish his studies before entering Marvin College, a Methodist school in Clinton that accepted younger students, in 1892.[15][16] The college's president offered him a scholarship that covered his academic expenses in exchange for his work as a janitor.[16] He allowed Barkley to miss the first and last month of the academic year to help on the family farm.[16] Barkley was active in the debating society at Marvin.[17] He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1897, and his experiences at Marvin persuaded him to convert to Methodism, the denomination with which he identified for the rest of his life.[13][16][18]

After graduation, Barkley went to Emory College (now part of Emory University) in Oxford, Georgia, the alma mater of several administrators and faculty members at Marvin.[19] During the 1897–1898 academic year, he was active in the debating society and the Delta Tau Delta fraternity, but he could not afford to continue his education and returned to Clinton after the spring semester.[20] He took a job teaching at Marvin College but did not make enough money to meet his basic living expenses.[6] He resigned in December 1898 to move with his parents to Paducah, Kentucky, the county seat of McCracken County, where his father found employment at a cordage mill.[21]

Early career

In Paducah, Barkley worked as a law clerk for Charles K. Wheeler, an attorney and congressman, accepting access to Wheeler's law library as payment for his services.[22] Despite their political differences – Wheeler supported William Jennings Bryan and Free Silver, while Barkley identified with the Gold Democrats – he hoped that being acquainted with and taught by Wheeler would aid him in his future endeavors, but congressional duties frequently kept Wheeler away from the office.[23] After two months, Barkley accepted an offer to clerk for Judge William Sutton Bishop and former congressman John Kerr Hendrick, who paid him $15 per month.[22] He read law while completing his duties and was admitted to the bar in 1901.[6] Barkley practiced in Paducah where a friend of Hendrick's appointed him reporter of the circuit court.[6] He continued studying law in the summer of 1902 at the University of Virginia School of Law.[24]

On December 19, 1904, Barkley declared his candidacy for county attorney of McCracken County well before the March 1905 Democratic primary.[25] The Republicans did not nominate a candidate, so the Democratic primary was the de facto general election.[26] Barkley faced two opponents in the primary – two-term incumbent Eugene A. Graves and Paducah Police Court Judge David Cross.[27] He organized his own campaign and made speeches across the county, showcasing his eloquence and likeability.[6] Graves received more votes than Barkley in Paducah, but McCracken County's rural farmers gave Barkley the victory, 1,525 votes to 1,096; Cross came in third with 602 votes.[27] This was the only time Barkley ever challenged an incumbent Democrat.[28]

Taking office in January 1906, Barkley saved taxpayers over $35,000 by challenging improper charges to the county.[26] He prosecuted two magistrates for approving contracts in which they had a conflict of interest.[29] Even Republicans admitted that he performed well, and he was chosen president of the State Association of County Attorneys.[6][26] During the 1907 gubernatorial campaign, he was the Democratic county spokesman, and despite his previous support for the Gold Democrats, he backed William Jennings Bryan in the 1908 presidential election.[30] Friends encouraged him to run for county judge, a powerful position which controlled county funds and patronage, and he announced his candidacy on August 22, 1908.[12][31] After the chairman of the county's Democratic Club Executive Committee endorsed him, the incumbent judge, Richard T. Lightfoot, retired rather than challenge him.[31][32]

On January 16, 1909, Democrat Hiram Smedley, county clerk since 1897, was indicted for embezzlement.[26] Smedley resigned, and Barkley was appointed to a three-man commission to investigate the losses.[26] The commission found $1,582.50 missing, and the county's Fiscal Court authorized Barkley to settle with the company that held Smedley's surety bond.[26] In May 1909, Smedley was arrested and charged with 20 counts of forgery, prompting an audit of the county's finances that showed a shortage of $16,000, only $6,000 of which was accountable to Smedley.[33] The scandal gave Republicans an issue for the upcoming campaign.[34] In a series of debates, Barkley's opponent, Thomas N. Hazelip, claimed that the county's entire Democratic organization was corrupt, and made charges against past Democratic administrations.[34][35] Barkley responded that he had no more responsibility for those wrongdoings than Hazelip had for the murder of William Goebel, a Democratic governor who had allegedly been assassinated by Republican conspirators in 1900.[36] He pointed to his improvement of the county's finances through inspection of charges presented to his office and showed evidence that he had fulfilled his obligations as county attorney, a fact Hazelip conceded.[37] In spite of the scandal, Democrats won every county-wide office, although by reduced margins, but Republicans captured a 5-to-3 majority on the Fiscal Court.[38] Barkley's victory margin—3,184 to 2,662—was the smallest of any county officer.[39]

At the Fiscal Court's January 1910 meeting, Barkley laid out an agenda to reduce the county's debt, improve its roads, and audit its books annually.[40] Despite the Republican majority on the Court, most of the measures he proposed during his term were adopted.[40] He appointed a purchasing agent and an inspector of weights and measures for the county, and allocated a salary for the county's almshouse keeper instead of relying on fees to fund the position.[40] He replaced the corvée system – wherein residents either paid a tax or donated labor to build and repair county roads – with private contracts.[41] The widening and graveling of county roads provided rural residents access to Paducah's amenities but reduced funds for programs such as free textbooks for indigents, and prevented Barkley from reducing the county's debt as planned.[42] When he named his father as the county's juvenile court probation officer, opponents charged him with nepotism.[41]

U.S. Representative (1913–1927)

Prompted by First District representative Ollie M. James' decision to seek election to the U.S. Senate in 1912, Barkley declared his candidacy for the district's congressional seat in December 1911.[43] Courting the votes of the district's farmers, Barkley advocated lower taxes and increased regulation of railroads by the Interstate Commerce Commission.[44] After one challenger withdrew in March, three more candidates entered the race – Trigg County Commonwealth's Attorney Denny Smith, Ballard County Judge Jacob Corbett, and John K. Hendrick, Barkley's former employer.[43] All were conservative Democrats who branded Barkley a socialist because he supported federal funding of highway construction.[44][45] Hendrick attacked Barkley's youth, inexperience and ambition to seek higher offices.[45] Barkley admitted his eventual desire for a Senate seat, and countered that Hendrick had also frequently sought office: "When the Pope died some years ago, nobody would tell Hendrick, for fear he would declare for that office."[45] Charging that Barkley's membership in Woodmen of the World was politically motivated, Hendrick ended up attacking the organization itself, angering the approximately 5,000 club members in the First District.[46] In June, the nomination of Woodrow Wilson for president and adoption of a progressive platform at the 1912 Democratic National Convention bolstered Barkley's candidacy.[44] He won 48.2% of the votes in the primary and went on to win the general election.[47]

Domestic matters

Initially conservative, working with Wilson (who was elected president) inspired Barkley to become more liberal.[13] On April 24, 1913, he first spoke on the House floor, favoring the administration-backed Underwood–Simmons Tariff Act which lowered tariffs on foreign goods.[48] He endorsed Wilson's New Freedom agenda, including the 1913 Federal Reserve Act and the 1914 Federal Trade Commission Act.[49] Because of his support for the administration, he was assigned to the powerful Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee and became the first freshman to preside over a session of the House.[50] As a member of the Interstate Commerce Commission, he supported the Clayton Antitrust Act and sought to end child labor in interstate commerce through the Keating–Owen Act in 1916.[44][51] He also supported measures to extend credit to and fund road improvements in rural areas.[24]

A speaker for the Anti-Saloon League, Barkley co-sponsored the 1916 Sheppard–Barkley Act which banned alcohol sales in Washington, D.C.[52][53] It was passed in 1917.[53] He sponsored an amendment to the Lever Food and Fuel Act forbidding the use of grain – rendered scarce by World War I and a poor harvest in 1916 – to make alcoholic beverages.[54] The amendment passed the House, but a conference committee amended it to allow production of beer and wine.[54] Both measures increased Barkley's national visibility and set the stage for future prohibition legislation, including the Eighteenth Amendment.[24] By 1917, the state Democratic Party was divided over prohibition, and the prohibitionist faction tried to enlist Barkley for the 1919 gubernatorial race.[55] The Memphis Commercial Appeal noted in late 1917 that Barkley had not declined the invitations, but his continued silence reduced the prohibitionists' enthusiasm.[55] He also showed little interest in the faction's attempts to recruit him to challenge anti-prohibitionist Ollie James in the 1917 Democratic Senate primary.[28]

By 1919, James had died in office, and Governor Augustus Owsley Stanley was elected to his vacant seat.[56] The divisive prohibition issue and recent Republican gains in the state made the Democratic gubernatorial primary of particular interest.[57] Stanley was the leader of the party's anti-prohibitionists.[57] Prohibitionists, led by former governor J. C. W. Beckham, did not support James D. Black, who became governor when Stanley went to the Senate and was seeking re-election.[57] At the time of Black's election as lieutenant governor in 1915, he had sided with the prohibitionists; he was chosen to run with Stanley to balance the party's ticket, so the anti-prohibitionists did not entirely trust him either.[57] Attempting to unite the party and prevent a Republican victory, Black invited Barkley, who had not been linked to either leader despite his support for prohibition, to be temporary chairman of the 1919 state Democratic convention.[58] Barkley's convention address attacked Republicans and praised the Democrats' record without making reference to prohibition, but many in the Beckham faction refused to accept Black, and he was defeated in the general election by Republican Edwin P. Morrow.[59] Chairing the convention introduced Barkley to state political leaders outside the First District.[60]

World War I

Barkley supported U.S. neutrality in World War I and endorsed Wilson's plan to purchase merchant ships for the U.S. instead of paying foreign carriers to travel waters containing German U-boats.[61] His position was popular in his district, as 80% of the dark tobacco grown in western Kentucky was sold overseas, and higher shipping costs adversely affected profits.[61] The House authorized the purchase, but Republicans and conservative Democrats in the Senate regarded the idea as socialistic and blocked its passage with a filibuster.[61]

Wilson supporters, including Barkley, campaigned for his re-election in 1916, using the slogan "he kept us out of war".[62] By early 1917, Germany had lifted all restrictions on attacks on neutral shipping supplying Britain and France, outraging many Americans.[62] The publication in February of the Zimmermann Telegram, in which a German official proposed to Mexico that, if the U.S. entered the war, Mexico should declare war on them and the Germans would work to return Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico to Mexican control, also brought the United States closer to war.[63] Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war on April 2, 1917, and Barkley voted for the resolution when it came before the House two weeks later.[63] At 40 years old, he considered resigning his seat to enlist in the U.S. Army, but Wilson persuaded him not to do so.[63]

After the declaration of war, Barkley supported bills implementing conscription and raising revenue for the fight.[54] Between August and October 1918, he joined an unofficial congressional delegation that toured Europe, surveying the tactical situation and meeting with leaders there.[63] Like Wilson, he supported U.S. ratification of the Treaty of Versailles and participation in the League of Nations, but both measures failed after the election of a more conservative Congress in 1918.[64]

Relations with Harding administration

Barkley supported William Gibbs McAdoo for president at the 1920 Democratic National Convention, but the nomination went to James M. Cox.[65] He campaigned for Cox and his running mate, Franklin D. Roosevelt, but his speeches focused more on Wilson's progressive record than Cox's fitness for office.[65] Republican Warren G. Harding defeated Cox in the general election, and Barkley found common ground with him on issues such as the creation of the Veterans' Bureau and the passage of the progressive Sheppard–Towner Act.[66] Barkley thought the administration was too favorable to big business interests, however, and in 1922 he proclaimed that if Harding had returned the country to normalcy, "then in God's name let us have Abnormalcy".[67]

Gubernatorial election of 1923

By the time of his 1922 re-election bid, Barkley was the ranking Democrat on the Interstate and Foreign Commerce Committee.[67] In the election, he carried every First District county, including the Republican strongholds of Caldwell and Crittenden counties.[67] Despite the victory he lacked the political organization needed for higher office.[68] According to Barkley biographer James K. Libbey, the establishment of such an organization, and not necessarily a desire to become governor, may have motivated him to announce his candidacy for the Democratic gubernatorial nomination on November 11, 1922.[68] Critics charged that this was his intent, and he did little to deny it.[69]

Opposing Barkley in the primary was Congressman J. Campbell Cantrill who, along with Stanley, led the conservative wing of the party, opposing prohibition and women's suffrage.[68][70] Beckham, leader of the liberal wing, intended to run, and his surrogates, particularly Louisville Courier-Journal editor Robert Worth Bingham, began a "Business Man for Governor" campaign in late 1922.[71] Beckham had served as governor from 1900 to 1907 and later in the U.S. Senate, but he was out of office (a "Business Man"), in contrast to Cantrill and Barkley.[71] While Bingham's campaign forced Barkley to declare his candidacy earlier than planned, the tactic was not successful outside Louisville; Beckham supporters backed Barkley, more to prevent Cantrill's nomination than because they desired Barkley's.[71] Barkley's leadership team included his own supporters, influential members of the Beckham faction, and erstwhile Cantrill supporters.[72][73]

Recognizing the need to broaden his appeal beyond western Kentucky, Barkley opened his campaign in the central Kentucky town of Danville on February 19, 1923.[73] He employed the slogan "Christianity, Morality, and Good Government", and he and Cantrill – colleagues in the House – agreed to refrain from personal attacks.[52][74] Due to Percy Haly's influence on Barkley, and Barkley's own admiration for Woodrow Wilson, he denounced the influence of the coal, racing, and railroad trusts in state politics.[52] "Woodrow Wilson drove the crooks and corruptionists out of New Jersey, Governor Pinchot is driving them out of Pennsylvania, and if I am elected Governor of Kentucky I promise to drive them out of Frankfort," he declared.[52] In contrast to his usual preference for low taxes, he advocated a tax on coal deposits.[72] In addition to reducing the coal trust's political influence, he believed the increased revenue, which would largely be generated by out-of-state coal buyers, would result in lower property taxes on farmers.[75] Friends in the Anti-Saloon League convinced him that banning parimutuel betting would cripple the racing trust.[52][75] Many Catholics and Protestants – notably those affiliated with the Louisville Churchmen's Federation – favored prohibition and opposed parimutuel betting on religious grounds, and endorsed Barkley's candidacy, but Bingham, typically a Beckham ally, was slow to endorse him.[72][76] Like Bingham, Lexington Herald editor Desha Breckinridge had helped create the parimutuel betting system, and Barkley's positions were enough to convince him to back Cantrill, despite the fact that Breckinridge generally disliked Cantrill.[72]

Barkley campaigned across the state, earning the nickname "Iron Man" for making up to 16 speeches in a day.[13] His proposals for a statewide highway system and improvements in education were popular, but coal mining and horse racing interests, based mostly in eastern Kentucky, opposed him.[44][70] Counties east of a line from Louisville to Middlesboro generally supported Cantrill, while those west of the line mostly went for Barkley, who lost the primary by 9,000 votes (out of 241,000 cast), marking his only election loss.[77][78] He supported Cantrill in the general election, gaining goodwill within the Democratic Party.[79] Cantrill died on September 2, and the Democratic State Committee had to name his replacement.[78] Barkley was not acceptable to many of the members of the committee, and he refused to accept nomination by party leaders instead of the voters.[80] On September 11, the committee nominated Congressman William J. Fields, and Barkley supported him in the general election, which he won over Republican Charles I. Dawson.[78][80]

Later House career

Barkley's party loyalty in the governor's race made him a formidable candidate to challenge Stanley, who by 1924 had angered members of both party factions, but Barkley had spent most of his funds in his campaign against Cantrill, and he did not want to risk his reputation as a party unifier by challenging a Democrat.[81] Instead, he decided to rebuild his war chest to unseat Kentucky's incumbent Republican senator, Richard P. Ernst, in 1926.[81] In the meantime, he refrained from using his influence in state races to avoid losing any goodwill with Kentucky voters.[82]

At the 1924 Democratic National Convention, Barkley again supported William G. McAdoo for president.[82] Urban interests at the convention promoted New York Governor Al Smith, and a bitter convention fight ensued.[82] During the course of 103 ballots, chairman Thomas J. Walsh needed a rest and temporarily yielded his position to Barkley.[82] The convention was the first to be broadcast nationally, and Barkley's service as chair augmented his national recognition and appeal.[24] The two Democratic factions agreed to compromise, nominating John W. Davis, who Libbey called a "competent nonentity"; Davis lost in the general election to incumbent Calvin Coolidge.[82] Barkley won another term in the House by a 2-to-1 margin over his Republican opponent in 1924, but Democratic divisions cost Stanley his Senate seat, and Barkley became even more convinced of the value of party loyalty.[82]

U.S. Senator (1927–1949, 1955–1956)

Because of Barkley's role in crafting the Railway Labor Act, the Associated Railway Labor Organizations endorsed him to unseat Ernst even before he formally announced his candidacy on April 26, 1926.[83] Since the 1923 gubernatorial contest, he had distanced himself from Haly and promised the conservatives that he would not push a ban on parimutuel betting if elected.[84] Consequently, he had no opposition in the primary.[44] Congressman (and later Chief Justice) Fred M. Vinson managed his general election campaign.[84]

Coolidge supported Ernst, and Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover campaigned in the state on his behalf.[85] Ernst had opposed a bonus for veterans of World War I, an unpopular position in Kentucky, and at 68 years old, his age worked against him.[84][86] Barkley contrasted his impoverished upbringing with Ernst's affluent lifestyle as a corporate lawyer, and also attacked him for supporting Michigan senator Truman Handy Newberry, who resigned due to allegations of election fraud.[85] Republican voters were angered that Ernst did not support Republican Congressman John W. Langley when Langley was charged with illegally aiding a large bootlegging operation in Louisville.[86] Ernst tried to resurrect the issues of Barkley's support for the coal tax and opposition to parimutuel betting, but in the general election, Barkley won by a vote of 287,997 to 266,657.[84]

In the Senate, Barkley was assigned to the Committee on the Library, and the committees on Finance and Banking and Currency; later, he was added to the Commerce Committee.[87] In early 1928, Vice President Charles G. Dawes assigned him to a special committee to investigate the campaign expenditures of the leading candidates in the upcoming presidential election.[87]

Democrats considered nominating him for vice president that year, calculating that his party loyalty and appeal to rural, agricultural and prohibitionist constituents could balance a ticket headed by likely presidential nominee Al Smith, an urban anti-prohibitionist.[88] When the Kentucky delegation arrived at the 1928 Democratic National Convention, they approached Smith supporters with a view to pairing Barkley to their candidate.[88] They were received cordially, but Smith's advisors thought placing candidates with such differing views on the ticket would seem contrived to the electorate.[89] They did not tell Barkley of their decision until after he seconded Smith's nomination for president.[89] Smith then announced Arkansas senator Joseph T. Robinson as his preferred running mate.[89] The Kentuckians nominated Barkley in spite of Smith's preference, but the overwhelming majority of delegates voted for Robinson, and Barkley announced that Kentucky was changing its support in order to make the nomination unanimous.[89]

Barkley and his wife Dorothy took a vacation after the convention, returning to Kentucky in August 1928 to find that, in his absence, Barkley had been chosen state chairman of Smith's campaign.[90] He campaigned for Smith, but Herbert Hoover won a landslide victory.[91] After the election, Barkley led a coalition of liberal Democrats and Republicans that opposed Hoover's use of protective tariffs, a debate that took particular urgency following the Wall Street Crash of 1929.[92] Barkley opposed the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act, claiming it would cost Americans both jobs and exports, but Congress approved it, and Hoover signed it on June 17, 1930.[93] When Congress adjourned, Barkley accompanied Sherwood Eddy and fellow senators Burton K. Wheeler and Bronson M. Cutting to the Soviet Union in August 1930.[93] He was impressed by the industrial development brought about by Joseph Stalin's first five-year plan but did not advocate closer diplomatic ties with the Communist nation, as some of his colleagues did.[94]

Barkley maintained that Hoover's response to the continuing depression and the severe drought in 1930 were inadequate, and pointed out that the $45 million in loans to farmers that he approved amounted to less than half the losses sustained by Kentucky's farmers alone.[95] He was angered that Hoover refused to call a special legislative session to adopt relief measures after the regular congressional adjourned in early March 1931.[95] He planned a series of speeches condemning Hoover beginning in June, but was injured in an automobile accident on June 22, limiting his political activities for the remainder of the year.[96]

Second term and ascension to floor leader

| External video | |

|---|---|

Barkley supported Franklin D. Roosevelt for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1932, but facing a re-election bid himself, he did not announce his support, fearing that his message might not resonate with Kentucky voters.[98] Roosevelt supporters offered Barkley the keynote address and temporary chairmanship of the 1932 Democratic National Convention if he would endorse their candidate.[99] Both opportunities would help Barkley's re-election chances, so he announced his support for Roosevelt on March 22.[99] In his keynote, Barkley warmly recalled the Wilson administration and denounced more than a decade of Republican dominance.[100] Applause frequently punctuated the speech, with the longest interruption – a 45-minute near-riot – erupting after Barkley called for a platform plank directing Congress to repeal prohibition.[100] According to Libbey, the remark was not a repudiation of his prohibitionist position but a desire for the people to express their will on repeal.[101] Prohibitionist constituents still supported Barkley because, for most of them, the depression trumped all other concerns.[101]

George B. Martin, who had served six months in the Senate in 1918 after being appointed to fill a vacancy, opposed Barkley in the 1932 primary, but Barkley defeated him by a two-to-one margin.[102] In the general election, he defeated Republican Congressman Maurice H. Thatcher by a vote of 575,077 to 393,865, marking the first time in the 20th century that a Kentucky senator won a second consecutive term.[103][104] Democrats gained control of the Senate during the 1932 elections; Joseph Robinson was chosen majority leader, and he appointed Barkley as his assistant.[13] Together, they secured passage of New Deal legislation, including the Agricultural Adjustment Act, the National Industrial Recovery Act, and the Federal Emergency Relief Act.[105] In July 1934, the Democratic National Committee chose Barkley to respond to Republican National Committee chairman Henry P. Fletcher's radio attacks on the New Deal.[106] Later that year, he embarked on a tour of twenty states, defending the New Deal and stumping for Democratic candidates in the 1934 midterm elections.[106]

Barkley was again the keynote speaker at the 1936 Democratic National Convention.[44] During his address, he alluded to the Supreme Court's decision in Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States – which struck down the National Industrial Recovery Act as unconstitutional – asking "Is the court beyond criticism? May it be regarded as too sacred to be disagreed with?"[107] These remarks help set an anti-Supreme Court tone for Roosevelt's second term.[108] On February 5, 1937, Roosevelt proposed legislation authorizing the president to appoint an additional justice for each one over the age of 70.[108] Many saw this proposal as an attempt to avoid further nullification of New Deal provisions as unconstitutional by appointing more sympathetic justices, and they dubbed the measure Roosevelt's "court-packing plan".[108]

.jpg.webp)

Barkley and Mississippi Senator Pat Harrison were the leading candidates to succeed Robinson as Democratic floor leader when he died on July 14, 1937.[13][102] Harrison's tenure in the Senate was eight years longer than Barkley's, and he was supported by conservative Southern Democratic senators opposed to Roosevelt's court-packing plan.[13] Harrison had helped secure Roosevelt's nomination at the 1932 Democratic National Convention by convincing Mississippi governor Martin Sennet Conner to keep his state's delegation loyal to Roosevelt, but Roosevelt preferred Barkley because of his support of the New Deal.[109] A letter from Roosevelt praising Barkley's legislative accomplishments and addressed to "My Dear Alben" was seen as an endorsement.[110] Although Roosevelt remained publicly neutral, he pressured Illinois' William H. Dieterich and Missouri's Harry S. Truman to support Barkley instead of Harrison; Dieterich acquiesced, but Truman remained loyal to Harrison.[110] Many senators resented Roosevelt's interference in a traditionally legislative prerogative.[110] Ultimately, Barkley was elected by a single vote.[111]

Challenge by Happy Chandler

Barkley faced a primary challenge in his 1938 re-election bid from A. B. "Happy" Chandler, Kentucky's popular governor who had a strong political organization throughout the state.[112] According to historian James C. Klotter, Chandler was confident of his ascension to the presidency and saw the Senate as a stepping stone.[113] Chandler twice asked Roosevelt to appoint Kentucky's junior Senator, M. M. Logan, to a federal judgeship so he could arrange his own appointment to Logan's Senate seat.[114] On one of these occasions – the retirement of Supreme Court Justice George Sutherland – Barkley advised Roosevelt to appoint Solicitor General Stanley Reed instead.[113] Chandler's mentor, Virginia senator Harry F. Byrd, and the bloc of Democrats who opposed Roosevelt's New Deal, then encouraged Chandler to announce his candidacy for Barkley's seat.[114][115]

The New York Times saw the primary as "the Gettysburg of the party's internecine strife" over control of the Democratic National Convention in 1940.[116] Early on, Chandler portrayed himself as a supporter of Roosevelt – since Roosevelt was popular in Kentucky – but opposed to the New Deal.[117] He pointed to his fiscal conservatism as governor, including reorganizing and downsizing the executive branch and reducing the state's debt.[113] Polls showing Barkley with a comfortable lead and an overwhelming victory by New Deal supporter Claude Pepper in Florida's May Senate primary convinced Chandler to shift his focus from the New Deal.[116] He criticized Barkley as "a stranger to the state" and obliquely referred to "fat, sleek senators who go to Europe and have forgotten the people of Kentucky except when they run for election".[117] Forty years old – 20 years Barkley's junior – he referred to Barkley as "Old Alben".[118]

Early in the contest, congressional business restricted Barkley's campaign to weekends, so he enlisted allies like Fred Vinson to speak on his behalf.[119][120] Chandler's political enemies such as former governor Ruby Laffoon, whom Chandler had crossed as lieutenant governor, and John Y. Brown, who felt that Chandler had broken a promise to support him for a seat in the Senate, also supported Barkley.[119] Although labor leaders had backed Chandler's gubernatorial bid, they endorsed Barkley because of Roosevelt's support for labor unions.[121] After the congressional session, Barkley resumed his "Iron Man" campaign style, making between 8 and 15 speeches each day and traveling, on average, 4,500 miles (7,200 km) per week.[122][119] This countered Chandler's implication that Barkley's age was a disadvantage, a charge that was further blunted when the younger Chandler fell ill in July, temporarily halting his campaigning.[119] Chandler indirectly charged that a Barkley supporter had poisoned his ice water, causing the illness.[123] Barkley ridiculed the suggestion, promising to appoint "an ice water guard" for his campaign.[123] During speeches, he would lift a glass of water to his lips, then mockingly inspect it and refuse to drink it.[123] Louisville police dismissed Chandler's claim as "a political bedtime story".[124]

Recognizing that the defeat of his hand-picked floor leader would be a repudiation of his agenda, Roosevelt began a tour of the state in Covington on July 8.[125] Chandler, the state's chief executive, was invited to welcome the president.[126] Although clearly campaigning for Barkley, Roosevelt made courteous remarks about Chandler in the spirit of party unity, but in Bowling Green, he chastised Chandler for "dragging federal judgeships into a political campaign".[112][127]

As nearly every 20th-century Kentucky governor had done, Chandler printed campaign materials with state funds, solicited campaign funds from state employees, and promised new government jobs in exchange for votes.[119] A later investigation determined that Chandler had raised at least $10,000 from state employees.[128] Federal New Deal employees countered by working on Barkley's behalf.[119] Barkley and George H. Goodman, director of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in Kentucky, denied that WPA employees played a role in the campaign, but journalist Thomas Lunsford Stokes concluded that "the WPA ... was deep in politics" in Kentucky, winning the 1939 Pulitzer Prize for Reporting for his investigation.[129] A Senate committee investigated Stokes' findings, and WPA administrator Harry Hopkins claimed the committee's report refuted all but two of Stokes' twenty-two charges.[130] Nevertheless, Congress passed the Hatch Act of 1939 which restricted federal employees' participation in political activities.[128]

Barkley won the August 6 election by a vote of 294,391 to 223,149, carrying 74 of Kentucky's 120 counties, with large majorities in western Kentucky, the city of Louisville, and rural areas.[123][128] It was the first loss of Chandler's political career, and the worst suffered by a primary candidate in Kentucky's history to that time.[131] Barkley defeated his Republican opponent, Louisville Judge John P. Haswell, securing 62% of the general election vote.[132] Encouraged by Barkley's success, Roosevelt campaigned against conservative Democratic incumbents in southern states, but all of these candidates won, which damaged Roosevelt's image.[133]

Floor leadership

With his caucus divided between conservatives and liberals, Barkley failed to secure passage for Roosevelt's court-packing plan.[44] After the successive failures of several administration-backed domestic bills, the press dubbed the Senate Majority Leader "bumbling Barkley".[111] He was able to salvage an appropriations bill to cover overspending by the WPA, although it allocated much less funding than Roosevelt had wanted.[132] He helped secure the Hatch Act, and The Washington Daily News called a 1940 amendment that prohibited campaigning by federally funded state employees a "monument to Alben Barkley's persistence and parliamentary skill".[126][132] Despite this mixed record, Roosevelt believed some Democratic partisans hoped to nominate Barkley for president at the 1940 Democratic National Convention, but the German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, deepened his resolve to seek a third term.[134]

Barkley disagreed with Roosevelt's selection of Agriculture Secretary Henry A. Wallace as his running mate; Libbey felt that "there is enough evidence from Barkley's tortuous private and public statements about the qualifications of Wallace to infer that Barkley wanted the vice presidency for himself", although he did not promote this idea to Roosevelt.[134] Barkley was chosen permanent chairman of the convention; chants of "We want Roosevelt" interrupted his July 16 speech for 20 minutes, indicating that he had created a popular mandate for Roosevelt's renomination, which occurred the next day.[135] Roosevelt went on to win an unprecedented third term in a landslide.[135]

Supporting Roosevelt's provision of aid to Allied Powers during World War II, Barkley sponsored the Lend-Lease Act in the Senate.[136] In November 1943, he helped draft the Connally–Fulbright Resolution for the creation of an international peace-keeping body at the end of the war, an idea he had favored since Woodrow Wilson's support of the League of Nations.[136] Supreme Court Justice and fellow Kentuckian Louis Brandeis influenced Barkley to adopt Zionism; during and after the war, Barkley advocated creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine and introduced a 1943 resolution demanding that the Nazis be punished for persecuting Jews.[24][136] U.S. entry into the war diverted Roosevelt's attention away from domestic affairs.[111] Vice President Wallace, House Speaker Sam Rayburn, Democratic House Floor Leader John William McCormack, and Barkley – the president's "Big Four" – helped develop and pass the administration's legislative agenda.[111] Barkley regularly met with the chairmen of the Senate's standing committees, forming a sort of legislative cabinet.[136] With their support, he secured passage of the War Powers Act and the Emergency Price Control Act.[137] He also advocated passage of a measure to outlaw poll taxes, but the bill was defeated.[138]

Split with Roosevelt

In April 1943 a confidential analysis by Isaiah Berlin of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee for the British Foreign Office described Barkley as "a Democratic party 'wheelhorse' who will pull the Administration wagon through thick and thin. Although he is the Majority Leader in the Senate, he is not an adroit negotiator, but a loyal supporter of the President come hell or high water."[139]

Tension developed between Roosevelt and Barkley during the war, however.[111] In 1943, Roosevelt refused to appoint Barkley to a vacancy on the Supreme Court, and Barkley criticized the War Production Board for awarding contracts for the production of war-related materials to large companies rather than small businesses.[24][138] Their most notable clash occurred in February 1944 when Roosevelt requested that Congress approve tax increases to generate over $10 billion in revenue for the war. Barkley and the Senate Finance Committee negotiated a bill containing only $2.3 billion in tax increases. Feeling the measure was insufficient, Roosevelt convened the "Big Four" on February 21 and told them he would veto it.[138] They urged him not to do so, assuring him that the bill they had drafted was the best one that they could pass.[138] Roosevelt vetoed the bill the next day, marking the first time a U.S. president vetoed a revenue bill.[111]

When Barkley entered the Senate chamber on February 23, word had spread that Roosevelt's veto had angered him.[140] He announced that he would resign as floor leader and encouraged his legislative colleagues to override the veto. He stated that Roosevelt's characterization of the bill as "providing relief not for the needy, but for the greedy" was "a calculated and deliberate assault upon the legislative integrity of every member of the Congress of the United States".[141] Roosevelt sent a letter to Barkley insisting he had not intended to impugn Congress' integrity and urging him not to resign. The next morning, Barkley resigned and left the Democratic Conference Room; minutes later, the caucus unanimously re-elected him. Many members who had seen Barkley as Roosevelt's advocate in Congress now looked upon him as Congress' advocate with Roosevelt.[111] Subsequently, Congress overwhelmingly overrode the veto.[141]

Barkley was among 12 nominated at the 1944 Democratic National Convention to be Roosevelt's running mate in the presidential election that year, receiving six votes.[142] Delegates favored replacing Vice President Henry Wallace on their ticket in favor of Barkley, but Roosevelt refused to consider him, telling a July 11 meeting of Democratic leaders that he was too old.[111][143] Instead, he took the recommendation of Democratic National Committee chairman Robert E. Hannegan and chose Harry S. Truman.[143] Despite his differences with Roosevelt, Barkley faced no serious challengers in the 1944 Democratic primary and defeated his Republican challenger, Fayette County Commonwealth's Attorney James Park, by a vote of 464,053 to 380,425.[144]

Buchenwald Concentration Camp

On April 11, 1945, U.S. forces liberated the Buchenwald concentration camp, established in 1937, where at least 56,545 people died. General Dwight D. Eisenhower left rotting corpses unburied so a visiting group of U.S. legislators could truly understand the horror of the atrocities. This group visited Buchenwald on April 24 to inspect the camp and learn firsthand about the enormity of the Nazi Final Solution and treatment of other prisoners.

The legislators included Barkley, Ed Izac, John M. Vorys, Dewey Short, C. Wayland Brooks, and Kenneth S. Wherry, along with General Omar Bradley and journalists Joseph Pulitzer, Norman Chandler, William I. Nichols, and Julius Ochs Adler.[145][146]

Truman succeeds Roosevelt

Truman ascended to the presidency when Roosevelt died in April 1945, just before the end of World War II.[111][147] In the war's aftermath, Americans wanted to know why the U.S. seemed ill-prepared for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.[147] Barkley sponsored a resolution to create the Joint Committee on the Investigation of the Pearl Harbor Attack and was chosen as chairman of the ten-person committee.[148] The committee's report, delivered on July 20, 1946, exonerated Roosevelt of any blame for the attack and highlighted weaknesses in communications between branches of the U.S. armed forces, leading to the creation of the United States Department of Defense.[148] Barkley also helped ensure U.S. participation in the United Nations and advocated approval of billions of dollars in loans to rebuild Europe.[148] Look magazine named him the second most fascinating person in the country behind Eisenhower.[149]

In the 1946 elections, Republicans wrested control of both houses of Congress from the Democrats for the first time since the Great Depression and gained control of the majority of state governments.[111][149] The power of labor unions had expanded under Roosevelt and the Democrats, and when a 1946 railroad worker strike exacerbated a post-war recession, the Republican majorities – over Barkley's objection – curbed union power via the Taft–Hartley Act.[150] They also passed the Twenty-second Amendment, limiting the president to two terms, a posthumous slap at Roosevelt.[151]

Barkley's wife became an invalid due to heart disease.[24] Barkley had closed his law practice when he was elected to the Senate, so to pay for his wife's care, he supplemented his $10,000 annual salary with speaking engagements.[143] He was the Democratic Speakers Bureau's most requested orator, surpassing Truman.[149] A Pageant magazine poll of legislators chose Barkley and Republican Robert A. Taft as the hardest-working members of their respective parties.[149] The Barkleys sold their Washington, D.C. home and moved into an apartment to reduce expenses.[147] Marny Clifford, wife of Truman's Naval Advisor Clark Clifford, nicknamed Barkley "Sparkle Barkle" for his care of his wife, who died March 10, 1947.[147] When Barkley won the Collier Award in May 1948, he donated the $10,000 prize to the University of Louisville School of Medicine in his wife's honor.[149]

Civil rights bills, unpopular with Southern Democrats, were central to Truman's Fair Deal.[151] Because Barkley could still appeal to Southern Democrats, Truman asked him to be the keynote speaker at the 1948 Democratic National Convention for an unprecedented third time.[152] Because of the Republican resurgence and Truman's difficulty appealing to some Democrats, Republican nominee Thomas E. Dewey was expected to win the upcoming presidential election.[152] Democrats were energized by Barkley's keynote address, which promoted New Deal accomplishments and called the Republican-controlled 80th Congress a "do nothing" Congress.[153] He mentioned Truman only once, leading Truman to suspect that Barkley sought to supplant him as the party's presidential nominee, but no such attempt occurred.[111] Despite these suspicions and his contention that a ticket consisting of a Missourian and a Kentuckian lacked regional geographic balance, convention delegates persuaded Truman to take Barkley as his running mate.[111] Truman had wanted Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, but Douglas declined.[143]

Barkley was disappointed that he was not Truman's first choice as running mate, but over the next six weeks, he crisscrossed the country by plane, making over 250 campaign speeches in 36 states.[153][154] Playing off Barkley's keynote speech, Truman called a special congressional session on July 26, challenging Republicans to enact their agenda.[155] They were unable to pass any significant legislation, seeming to confirm Barkley's characterization of them as a "do-nothing Congress".[155]

Vice presidency (1949–1953)

In an upset victory, Truman and Barkley were elected over the Republican ticket by over 2 million votes, and Democrats regained majorities in both houses of Congress.[156] 71 years old at the time of his inauguration, he was (and still is) the oldest man ever elected vice president, breaking Charles Curtis' record at 69.[44][157] His grandson, Stephen M. Truitt, suggested the nickname "Veep" as an alternative to "Mr. Vice President".[158] The nickname was used by the press, but Barkley's successor, Richard Nixon, discontinued using it, saying it belonged to Barkley.[157]

Despite their personal differences, Truman and Barkley agreed on most issues.[154] Because of Barkley's legislative experience, Truman insisted his vice president attend cabinet meetings.[44] Barkley chaired the Senate Democratic Policy Committee and attended Truman's weekly legislative conferences.[159] When Congress created the National Security Council, it included the vice president as a member.[160] Barkley acted as the administration's primary spokesperson, making 40 major speeches in his first eight months in office.[160] Truman commissioned the United States Army Institute of Heraldry to create a seal and flag for the vice president, advocated raising his salary, and increased his expense budget.[44][161] Mark Hatfield's biographical sketch of Barkley noted that he was "the last [vice president] to preside regularly over the Senate, the last not to have an office in or near the White House, [and] the last to identify more with the legislative than the executive branch".[157]

Despite the Democrats' advantage in the Senate, conservative Democrats united with the Republican minority to oppose much of Truman's agenda, most notably, civil rights legislation.[162] In March 1949, Democratic floor leader Scott W. Lucas introduced an amendment to Senate Rule XXII to make cloture easier to achieve, hoping to end a ten-day filibuster against a civil rights bill.[163] Conservative Republicans and Southern Democrats opposed the rule change and tried to obstruct it.[163] Lucas asked for a cloture vote on the rule change, but opponents contended that the motion was out of order.[163] Barkley studied the original debate on Rule XXII, which governed both cloture motions, before ruling in Lucas' favor.[164] Georgia senator Richard Russell Jr. appealed Barkley's decision, and the chamber voted 46–41 to overrule.[164] Sixteen Republicans, mostly from Northeast and West Coast states, voted to sustain the ruling; most Southern Democrats voted with the remaining Republicans to overrule it.[164]

On July 8, 1949, Barkley met Jane (Rucker) Hadley, a St. Louis widow approximately half his age, at a party thrown by Clark Clifford.[157][165] After Hadley's return to St. Louis, Barkley kept contact with her via letters and plane trips.[165] Their courtship received national attention, and on November 18, they married in the Singleton Memorial Chapel of St. John's Methodist Church in St. Louis, the event televised nationally.[166] Barkley is the only U.S. vice president to marry while in office.[44]

Barkley's most notable tie-breaking vote as vice president was cast on October 4, 1949, to save the Young–Russell Amendment which set a 90% parity on the price of cotton, wheat, corn, rice, and peanuts.[167] His friends, Scott Lucas and Clint Anderson, opposed the amendment, but Barkley had promised support during the 1948 campaign.[167]

In 1949, Emory University chose Barkley to deliver its commencement address and awarded him an honorary Doctor of Laws.[168] The following year, the university's debating society renamed itself the Barkley Forum.[169] The university also created the Alben W. Barkley Distinguished Chair in its Department of Political Science.[169]

Barkley tried to mentor Scott Lucas and Ernest McFarland, his immediate successors as floor leader, by teaching them to work with the vice president as he had during Truman's vice presidency, but Truman's unpopularity made cooperation between the executive branch and the legislature difficult.[162] After the U.S. entered the Korean War, Truman focused on foreign affairs, leaving Barkley to campaign for Democratic candidates in the 1950 midterm elections.[161] He traveled over 19,000 miles (31,000 km) and spoke in almost half of the states during the campaign.[170] He felt ill when he arrived in Paducah on election day, and a doctor diagnosed him with a "tired heart".[171] Returning to Washington, D.C., he spent several days in the Bethesda Naval Hospital, but was able to preside when the Senate opened its session on November 28.[171] Democrats lost seats in both houses but maintained majorities in each.[161]

On March 1, 1951 – exactly 38 years from his first day in Congress – Barkley's fellow congressmen presented him with the Congressional Gold Medal in honor of his legislative service.[172] Truman surprised Barkley, appearing on the Senate floor to present the medallion and a gavel made of timbers used to renovate the White House after the burning of Washington in 1814.[171]

In November 1951, Barkley and his wife ate Thanksgiving dinner with U.S. troops at Kimpo Air Base in Seoul.[173] On his 74th birthday, Barkley traveled to the front lines on a fact-finding mission for the president.[173] On June 4, 1952, he cast another notable tie-breaking vote to save the Wage Stabilization Board.[174]

Campaign for president

At the March 29, 1952 Jefferson–Jackson Day fundraiser, Truman announced that he would not seek re-election, although he was exempt from the Twenty-second Amendment's term limits.[175] After the announcement, the District of Columbia Democratic Club formed a Barkley for President Club with Iowa senator Guy Gillette as chairman.[174] Prominent Kentuckians – including senator Earle C. Clements, governor Lawrence Wetherby, and lieutenant governor Emerson "Doc" Beauchamp – supported the candidacy.[174] Exactly two months after Truman's announcement, Barkley declared his availability to run for president while maintaining he was not actively seeking the office.[176]

Barkley's distant cousin, Illinois Governor Adlai Stevenson II (grandson of Adlai Stevenson I), was considered his primary competition for the presidential nomination, but had not committed before the convention.[176] Richard Russell Jr. and Tennessee senator Estes Kefauver were also interested in the nomination.[177] Kentucky's delegation to the 1952 Democratic National Convention announced that they would support Barkley, and Truman encouraged Missouri's delegates to do so.[176] Democratic National Committee chairman Frank E. McKinney, former chairman James Farley, and Senate Secretary Leslie Biffle also supported him.[178] Two weeks before the convention, Stevenson advisor Jacob Arvey told Barkley that Stevenson was not going to be nominated and favored nominating Barkley.[178] Barkley's advisors believed that Kefauver and Russell would knock each other out of the early balloting, allowing Barkley to capture the nomination.[177]

To dispel concerns about his age (74), failing eyesight, and heart problems, Barkley arrived in Chicago for the convention and briskly walked seven blocks from the bus station to his campaign headquarters.[177][178] The attempt was rendered moot on July 20 when a group of labor leaders, including United Automobile Workers president Walter Reuther, issued a statement calling Barkley too old and requesting that Democrats nominate someone younger like Stevenson.[179] At a meeting with labor leaders the next morning, Barkley failed to persuade them to retract the statement, which caused delegations from large industrial states like Illinois, Indiana, and Pennsylvania to waver on their commitments to Barkley.[179][180] On July 21, he announced his withdrawal from the race.[179] Invited to make a farewell address on July 22, he received a 35-minute ovation when he took the podium and a 45-minute one at the speech's end.[161][181] In a show of respect, a Missouri delegate nominated Barkley for president and House Majority Leader McCormack seconded it, but Stevenson was easily nominated.[182] A month after the convention, Barkley hosted a Stevenson picnic and campaign rally at his home in Paducah and later introduced him at a rally in Louisville.[183] Despite Barkley's predictions of a Democratic victory, Stevenson lost in overwhelming fashion to Republican Dwight Eisenhower.[184]

Post-vice presidency (1953–1956)

Barkley's term as vice president ended on January 20, 1953.[18] After the election, he had surgery to remove his cataracts.[184] He contracted with NBC to create 26 fifteen-minute commentary broadcasts called "Meet the Veep".[184] Low ratings prompted NBC's decision not to renew the series in September 1953.[184] In retirement, Barkley remained a popular speaker and began working on his memoirs with journalist Sidney Shallett.[184] He re-entered politics in 1954, challenging incumbent Republican senator John Sherman Cooper.[185] In a 1971 study of Barkley's Senate career, historian Glenn Finch argued that Barkley was the only person who could beat Cooper.[186] Few issues differentiated the candidates, and the campaign hinged on party politics; visits to Kentucky by President Eisenhower, Vice President Richard Nixon, and Illinois senator Everett Dirksen on Cooper's behalf reinforced this notion.[184] Barkley resumed his Iron Man campaign style, campaigning for up to sixteen hours a day, countering the "too old" charge that had cost him the 1952 Democratic presidential nomination.[187] He won the general election by a vote of 434,109 to 362,948, giving Democrats a one-vote advantage in the Senate.[161][183]

Veteran West Virginia senator Harley M. Kilgore offered to exchange seats with Barkley, putting Barkley on the front row with the chamber's senior members and himself on the back row with the freshman legislators, but Barkley declined the offer.[188] In honor of his previous service, he was assigned to the prestigious Committee on Foreign Relations.[44] In this position, he endorsed Eisenhower's appointment of Cooper as U.S. Ambassador to India and Nepal.[188] His relative lack of seniority did not afford him much influence.[188] Barkley did not sign the 1956 Southern Manifesto despite school segregation being legally required in Kentucky prior to Brown v. Board of Education (1954).[189]

Death

In a keynote address at the Washington and Lee Mock Convention on April 30, 1956, Barkley spoke of his willingness to sit with the other freshman senators in Congress; he ended with an allusion to Psalm 84:10, saying "I'm glad to sit on the back row, for I would rather be a servant in the House of the Lord than to sit in the seats of the mighty."[161] He then collapsed onstage and died suddenly of a heart attack, aged 78.[44] He was buried in Mount Kenton Cemetery near Paducah.[18]

Personal life

Barkley joined the Broadway Methodist Episcopal Church, where he was a lay preacher, and several fraternal organizations, including Woodmen of the World, the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, the Independent Order of Odd Fellows, and the Improved Order of Red Men.[190] On June 23, 1903, he married Dorothy Brower (November 14, 1882 – March 10, 1947).[6] They had three children: David Murrell Barkley (1906–1983), Marion Frances Barkley (1909–1996), and Laura Louise Barkley (1911–1987).[6][190] Laura Louise married Douglas MacArthur II, a U.S. diplomat and nephew of General Douglas MacArthur.[122]

Legacy

A dam constructed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers on the Cumberland River in 1966, and the lake it forms, were named Barkley Dam and Lake Barkley in Barkley's honor.[191] Barkley Regional Airport in Paducah is also named for him.[192] In 1984, the federal government declined to purchase The Angles, his Paducah home, and it was sold at auction.[193] Many personal items owned by Barkley are displayed on the second floor of the historic house Whitehaven in Paducah. In February 2008, Paducah's American Justice School of Law changed owners after failing to secure accreditation from the American Bar Association.[194] It was renamed the Alben W. Barkley School of Law, but remained unaccredited, and closed in December 2008.[194]

References

- James K. Libbey, Alben Barkley: A Life in Politics (2016) ch 1-7.

- James K. Libbey, Alben Barkley: A Life in Politics (2016) ch 8-12.

- Roosevelt, Franklin D. (January 1950). Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: F.D. Roosevelt, 1944 ... Best Books on. ISBN 9781623769734. Archived from the original on January 8, 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- Finch, p. 167

- James K. Libbey, Alben Barkley: A Life in Politics (2016) ch 13-16.

- Libbey in The Kentucky Encyclopedia, p. 52

- Libbey in Dear Alben, pp. 1, 3

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 1

- Libby in Dear Alben, p. 3

- Witcover, Jules (2014). "35. Alben W. Barkley". The American Vice Presidency: From Irrelevance to Power. Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1588344717.

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 2

- Finch, p. 286

- Hatfield, p. 2

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Clinton Days", p. 343

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Clinton Days", p. 346

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 5

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 6

- "Barkley, Alben William". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Clinton Days", p. 358

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Clinton Days", p. 360

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Clinton Days", p. 361

- Libbey in "The Making of the 'Paducah Politician'", p. 255

- Libbey in "The Making of the 'Paducah Politician'", pp. 251–252

- "Alben William Barkley". Dictionary of American Biography

- Libbey in "The Making of the 'Paducah Politician'", p. 266

- Grinde in "Politics and Scandal", p. 37

- Libbey in "The Making of the 'Paducah Politician'", p. 268

- Grinde in "Gentle Partisan", p. 249

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Rise", p. 264

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Rise", pp. 261, 266

- Grinde in "Politics and Scandal", p. 39

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Rise", p. 266

- Grinde in "Politics and Scandal", pp. 37–38

- Grinde in "Politics and Scandal", p. 38

- Grinde in "Politics and Scandal", p. 42

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Rise", p. 270

- Grinde in "Politics and Scandal", p. 45

- Grinde in "Politics and Scandal", pp. 49, 51

- Grinde in "Politics and Scandal", p. 50

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Rise", p. 271

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Rise", p. 272

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 13

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 14

- Libbey in The Kentucky Encyclopedia, p. 53

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Rise", p. 276

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Rise", p. 277

- Libbey in "Alben Barkley's Rise", p. 278

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 20

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 22

- Libbey in Dear Alben, pp. 22–23

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 27

- Sexton, p. 53

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 28

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 31

- Grinde in "Gentle Partisan", p. 248

- Grinde in "Gentle Partisan", pp. 250–251

- Grinde in "Gentle Partisan", p. 251

- Grinde in "Gentle Partisan", p. 252

- Grinde in "Gentle Partisan", pp. 254–257

- Grinde in "Gentle Partisan", p. 257

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 25

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 29

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 30

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 32

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 33

- Libbey in Dear Alben, pp. 33–34

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 34

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 37

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 36

- Harrison and Klotter, p. 352

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 38

- Klotter, p. 272

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 39

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 40

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 41

- Hill, p. 120

- Harrison and Klotter, p. 353

- Finch, p. 287

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 42

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 43

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 44

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 45

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 46

- Klotter, p. 284

- Finch, p. 288

- Harrison and Klotter, p. 355

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 50

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 52

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 53

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 54

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 55

- Libbey in Dear Alben, pp. 56–57

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 57

- Libbey in Dear Alben, pp. 58–59

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 59

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 60

- "Life and Career of Senator Alben Barkley". C-SPAN. June 30, 2014. Archived from the original on May 17, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2016.

- Libbey in Dear Alben, pp. 60–61

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 61

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 62

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 63

- Finch, p. 289

- Klotter, p. 299

- Harrison and Klotter, p. 363

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 66

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 67

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 71

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 72

- Finch, pp. 290–291

- Finch, p. 290

- Hatfield, p. 3

- Harrison and Klotter, p. 369

- Klotter, p. 312

- Finch, p. 291

- Hixson, p. 313

- Hixson, p. 316

- Hixson, p. 314

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 78

- Klotter, p. 313

- Hixson, p. 315

- Hixson, p. 327

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 79

- Harrison and Klotter, p. 370

- Hixson, p. 324

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 80

- Hixson, p. 321

- Hixson, p. 322

- Klotter, p. 315

- Klotter, p. 314

- Hixson, p. 317

- Hixson, p. 326

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 81

- Hixson, p. 329

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 82

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 83

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 84

- Libbey in Dear Alben, pp. 84–85

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 85

- Hachey, Thomas E. (Winter 1973–1974). "American Profiles on Capitol Hill: A Confidential Study for the British Foreign Office in 1943" (PDF). Wisconsin Magazine of History. 57 (2): 141–153. JSTOR 4634869. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 21, 2013.

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 86

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 87

- Catledge, Turner (July 22, 1944). "Truman Nominated for Vice Presidency". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 6, 2013. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- Finch, p. 294

- Finch, p. 293

- "American Congressmen and reporters visit Buchenwald, April 24, 1945". www.scrapbookpages.com. Archived from the original on November 18, 2020. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- "American congressmen view the open ovens in the Buchenwald crematorium". collections.ushmm.org. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2019.

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 90

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 91

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 92

- Libbey in Dear Alben, pp. 92–93

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 93

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 94

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 95

- Hatfield, p. 4

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 96

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 98

- Hatfield, p. 1

- Davis, p. 115

- Davis, p. 121

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 100

- Hatfield, p. 6

- Hatfield, p. 5

- Davis, p. 116

- Davis, p. 117

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 101

- Davis, p. 119

- Davis, p. 118

- "A History of Commencement at Emory". Emory University

- "Alben William Barkley". University of Virginia

- Davis, p. 122

- Davis, p. 123

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 102

- Davis, p. 125

- Davis, p. 126

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 104

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 105

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 106

- Davis, p. 127

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 107

- Davis, p. 128

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 108

- Libbey in Dear Alben, pp. 109–110

- Davis, p. 130

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 110

- Harrison and Klotter, p. 402

- Finch, p. 295

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 112

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 113

- "Senate – March 12, 1956" (PDF). Congressional Record. U.S. Government Printing Office. 102 (4): 4459–4461. Retrieved April 12, 2023.

- Libbey in Dear Alben, p. 10

- "Lake Barkley". Lake Productions, LLC.

- Poore, "Challenger Pounds Home His Message"

- "Alben Barkley Home, Effects to be Sold". Lexington Herald-Leader

- Martin, "Attorney General Conway Concludes Investigation into Student Loan Company Involved with Bankrupt West Kentucky Law School"

Bibliography

- "Alben Barkley Home, Effects to be Sold". Lexington Herald-Leader. March 21, 1984. p. B1.

- "Alben William Barkley". Dictionary of American Biography. New York City: Charles Scribner's Sons. 1936. Archived from the original on March 22, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- "Alben William Barkley". University of Virginia. Archived from the original on July 28, 2013. Retrieved October 6, 2012.

- "Barkley, Alben William". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. United States Congress. Archived from the original on September 13, 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- Davis, Polly Ann (April 1978). "Alben W. Barkley: Vice President". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 76 (2).

- Finch, Glenn (July 1971). "The Election of United States Senators in Kentucky: The Barkley Period". Filson Club History Quarterly. 45 (3).

- Grinde, Gerald S. (Summer 1980). "The Emergence of the 'Gentle Partisan': Alben W. Barkley and Kentucky Politics, 1919". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 78 (3). online

- Grinde, Gerald S. (April 1976). "Politics and Scandal in the Progressive Era: Alben W. Barkley and the McCracken County Campaign of 1909". Filson Club History Quarterly. 50 (2).

- Harrison, Lowell H.; James C. Klotter (1997). A New History of Kentucky. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2008-X. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- Hatfield, Mark O. (1997). "Alben W. Barkley (1949–1953)" (PDF). Vice presidents of the United States, 1789–1993. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 24, 2012. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- Hill, Samuel S. (1983). Religion in the Southern States: A Historical Study. Macon, Georgia: Mercer University Press. ISBN 0-86554-045-4. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- "A History of Commencement at Emory". Emory University. Archived from the original on May 5, 2012. Retrieved October 6, 2012.

- Hixson, Walter L. (Summer 1982). "The 1938 Kentucky Senate Election: Alben W. Barkley, 'Happy' Chandler, and the New Deal". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 80. online

- Klotter, James C. (1996). Kentucky: Portraits in Paradox, 1900–1950. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-916968-24-3. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- "Lake Barkley". Lake Productions, LLC. Archived from the original on August 18, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2012.

- Libbey, James K. Alben Barkley: A Life in Politics (University Press of Kentucky, 2016). excerpt, standard scholarly biography

- Libbey, James K. (Autumn 1980). "Alben Barkley's Clinton Days". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 78 (4).

- Libbey, James K. (Summer 2000). "Alben Barkley's Rise from Courthouse to Congress". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 98 (3).

- Libbey, James K. (Summer 1998). "Alben W. Barkley: The Making of the 'Paducah Politician'". The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 96 (3).

- Libbey, James K. (1979). Dear Alben: Mr. Barkley of Kentucky. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-0238-3. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- Libbey, James K. (1992). "Barkley, Alben William". In John E. Kleber (ed.). The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Associate editors: Thomas D. Clark, Lowell H. Harrison, and James C. Klotter. Lexington, Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-1772-0. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2012.

- Martin, Allison Gardner (September 28, 2010). "Attorney General Conway Concludes Investigation into Student Loan Company Involved with Bankrupt West Kentucky Law School". U.S. Federal News Service. Archived from the original on April 9, 2016. Retrieved October 6, 2012.

- Poore, Chris (November 3, 1993). "Challenger Pounds Home His Message". Lexington Herald-Leader. p. A1.

- Sexton, Robert F. (January 1976). "The Crusade Against Pari-mutuel Gambling in Kentucky: a Study of Southern Progressivism in the 1920s". Filson Club History Quarterly. 50 (1).

Further reading

Primary sources

- Barkley, Alben (1954). That Reminds Me. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 9780598754448. OCLC 456611.

- Barkley, Alben (1959). Veep: Former Vice President Alben W. Barkley Tells His Own Story. New York City: Folkways Records. ISBN 9780598754448. OCLC 692298110.

- Barkley, Jane Rucker Hadley (1958). I Married the Veep. New York City: Vanguard. OCLC 1368739.

Secondary sources

- Davis, Polly (1976). "Court Reform and Alben W. Barkley's Election as Majority Leader". Southern Quarterly. 15 (1): 15–31.

- Davis, Polly Ann (1977). "Alben W. Barkley's Public Career in 1944". Filson Club History Quarterly. 51 (2): 143–157.

- Libbey, James K. (2016). Alben Barkley: A Life in Politics. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky. ASIN B015JUDXZO.

- Pietrusza, David (2011). 1948: Harry Truman's Improbable Victory and the Year that Changed America. Union Square Press. ISBN 978-1-4027-6748-7.

- Ritchie, Donald A. (1991). "Alben Barkley". In Richard A. Baker and Roger H. Davidson (ed.). First Among Equals: Outstanding Senate Leaders of the Twentieth Century. CQ Press.

- Robinson, George W. (1969). "Alben Barkley and the 1944 Tax Veto". Register of the Kentucky Historical Society. 67 (3): 197–210. online

External links

- United States Congress. "Alben W. Barkley (id: B000145)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Barkley Collection – Barkley's Papers at the University of Kentucky Archived September 6, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- Newspaper clippings about Alben W. Barkley in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW