Alexander Earle Monteith

Alexander Earle Monteith (1793 – 12 January 1861) trained as a lawyer in Edinburgh and became Sheriff of Fife in 1838. He is remembered as one of the Disruption Worthies - those church leaders who, at the Disruption of 1843, left to set up the Free Church of Scotland. Monteith was an active member of many commissions involved in reforming Aberdeen University, prisons and treatment of those then called lunatics for example. Monteith was also photographed by Hill & Adamson and by his second wife, Frances, who herself was an early pioneer of calotype photography and some of whose pictures ended up in an album by David Brewster.

Alexander Earle Monteith | |

|---|---|

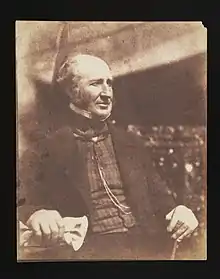

Alexander Earle Monteith by Hill & Adamson | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1793 |

| Died | 12 January 1861 |

Early life and ancestry

Alexander Earle Monteith, was born in 1793, and passed advocate in Edinburgh in 1810. His father was Mr Robert Monteith of Rochsoles, whose brother, Henry Monteith of Carstairs, for some years represented the city of Glasgow in Parliament. His paternal grandfather was James Monteith of Anderson.[1] Before he reached manhood, his father died, and he thenceforth resided with his mother and sister in Edinburgh.[2][3]

Legal career

He served his apprenticeship with Archibald Swinton, Esq., Writer to the Signet, in whose office Mr Conelly, Town Clerk of Anstruther, was then a clerk, and after attending the law classes, and entering upon his profession, Mr Monteith became intimate with lawyers such as Jeffrey, Cranstown, Clerk, Moncreiff, Cockburn, Murray, Fullerton, and Rutherford. His early success at the bar was great and rapid. It has been matter of surprise that with qualities so fitted apparently to command permanent success at the bar, he failed to maintain his practice. This was to a large extent attributable to a severe attack of illness, which continued throughout almost the whole of the years 1840–1841, and which withdrew him during that period from the active duties of his profession, and interrupted the prosperous career in which he seemed to have entered. In part also, however, it arose from the circumstance that he could not sufficiently submit himself to some of the factitiously conventional rules of which an advocate's devotion to his profession is tried at the Scottish bar, or rather by the Edinburgh agents. Monteith never appears to have enjoyed the favour of the Inner Council, by which the exercise of Scottish professional patronage was directed ; and with the exception of the Sheriffdom of Fife, bestowed on him in 1838, while Lord Murray was Lord-Advocate, a situation far within his merits, he received no appointment from Government. His judgments were rarely appealed against, and still more rarely reversed.[2][3]

Other involvements

Although the Sheriffship of Fife was the only remunerative office ever conferred on him, he had several times an opportunity of giving his gratuitous services on subjects of public importance. He served on the Royal Commission regarding the Aberdeen Universities, and, it is understood, prepared the report which formed the foundation of the union. He served also on the Lunacy Commission, whose labours brought fully to light the evils, as they secured the overthrow of that fearful system of confinement in private houses which had previously so largely prevailed. He was likewise a member of the commission for enquiring into the working of the Forbes Mackenzie Act; and in this as in two other Commissions, he took a large share in the labour, and in the preparation of the reports presented by these Commissions and laid before Parliament. He was at the same time a member of the General Prison Board, and latterly was for some years Convener of the committee for managing the Central Prison at Perth, in which capacity he devoted himself to the working out of the system of discipline there put in operation. He had, prior to the passing of the Prisons' Act, been an active member of the Association for the Improvement of Prison Discipline in Scotland, which led the way to the passing of that act, and to the great amelioration in the state of Scottish prisons, and in their internal management.[2][3]

Church involvements

In his younger days, with other members of his family, he was an Episcopalian. He attended Dr Alison's church, and afterwards Bishop Sandford's. The first of his family who adopted evangelical views was his sister, Mrs Stothert of Cargen, who was next to him in age, and he often argued with her about her new opinions. He considered himself abler than she was, yet he felt she had often the best of the argument. At this time he went to hear Thomas Chalmers. In the sermon a character was described of great moral excellence, and as he listened, he wished his sister could be present to hear how differently Chalmers judged of human nature from the way in which she did. Presently the preacher proceeded to shew, that as rebels might be just and fair in their dealings one with another, while they were traitors to their lawful sovereign, so all he had described might consist with entire alienation of the heart from God, and entire disregard of His authority. This Mr Monteith used to refer to as his first lesson in the doctrine of the depravity of human nature. But Chalmers' sermon seems to have had a wider and a deeper influence — at least it was after it that he began the regular reading of his Bible, writing down as he read what each book or passage seemed to teach, and summing up its doctrines and lessons. In this way he went through the whole of the Scriptures, and came substantially to the views which he ever afterwards held. He left the Episcoplian Church, attaching himself to the ministry of the Rev. Dr Gordon.[4] He later became an elder of the High Church congregation, of which his friend, Robert Gordon, was minister, and he not only gave diligent attendance at the meetings of Session, but had a district in one of the closes of the High Street in which he faithfully visited the inhabitants individually — maintained a stated prayer meeting - and assisted to keep up a school for the children. Of the higher Church Courts he was a prominent and influential member ; and in the long contest which issued in the Disruption, he was a very active member both in counsel and in debate.[2][3]

Final days

In his later years, Monteith's health began to give way, as the result of heart disease, with which he knew he was afflicted. In his journal, he more than once referred to this. In his case, the end came sooner than his friends expected. He died on 12 January 1861.[4]

Family

He married:

- At No. 20, Windsor-street, on the 15 July 1829, Emma (died 1831[5]), second daughter of the late Richard Clay, Esq. of London and had issue-[6]

- Mary Anna

- Frances, the younger daughter of James Dunlop, who became his wife, in 1838.[7] She was one of the pioneers of calotype photography. She died in 1898.[8] Frances and Alexander had issue-

- Anna Julia born 19 September 1842.[5]

Monteith had two daughters.[4] Alexander's nephew, James Macphail, named his younger son Earle Monteith Macphail (1861-1937). Earle was a missionary to India who became principal (1921) and vice-chancellor (1923-5) of Madras University and rose to a senior position in colonial politics, rising to become deputy chairman of the Legislative Assembly of India in 1927.[9]

References

Citations

- Stewart 1881.

- Conolly 1866.

- Monteith & Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop 1852.

- Wylie 1881.

- Teanby 2021.

- Henry & Wells 1829.

- Anderson 1877.

- FRSE 2006.

- "Macphail Papers". Mundus. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

Sources

- Anderson, William (1877). "Dunlop, James". The Scottish nation: or, The surnames, families, literature, honours, and biographical history of the people of Scotland. Vol. 2. A. Fullarton & co. p. 106.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Brown, Thomas (1893). Annals of the disruption with extracts from the narratives of ministers who left the Scottish establishment in 1843 by Thomas Brown. Edinburgh: Macniven & Wallace. p. 52.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Burns, George; Candlish, Robert S.; Monteith, Alexander Earle (1839). Report of Speeches of the Rev. Dr. Burns, Rev. Robert S. Candlish, and Alexander Earle Monteith, Esq., in the General Assembly, on Wednesday, May 22, 1839. In the Auchterarder Case. Revised by the Speakers. With an Appendix, Containing Reasons of Adherence to the Church of Scotland ; and Answers to the Various Reasons of Dissent from the Decision of the Assembly. Edinburgh: John Johnstone.

- Burns, James Chalmers (1858). Memorial of the Late James Maitland Hog, Esq. of Newliston By James C. Burns. Edinburgh: John MacLaren. p. 44.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Buchanan, Robert (1854). The ten years' conflict : being the history of the disruption of the Church of Scotland. Vol. 2. Glasgow ; Edinburgh ; London ; New York: Blackie and Son. pp. 349.

- Conolly, Matthew Forster (1866). Biographical dictionary of eminent men of Fife of past and present times : natives of the county, or connected with it by property, residence, office, marriage, or otherwise. Edinburgh: Inglis & Jack. pp. 334-337.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Henry, Diana; Wells, Robert (1829). The Dumfries Weekly Journal And Nithsdale, Annandale, and Galloway Advertiser Birth, Marriage and Death Notices Transcribed by Diana Henry and Robert Wells (PDF). p. 29.

- Maclagan, David (1876). St. George's, Edinburgh. London, Edinburgh and New York: T. Nelson and sons. pp. 74, 164.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Monteith, Alexander Earle of; Colquhoun-Stirling-Murray-Dunlop, Alexander (1852). Two letters of the Late Alexander Earle of Monteith, Sheriff of Fife on the evidences of revealed religion. With a memoir by A.M. Dunlop. Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Stewart, George (1881). Curiosities of Glasgow citizenship; as exhibited chiefly in the business career of its old commercial aristocracy. Glasgow: James Maclehose. pp. 93-116.

- Teanby, Rose (2021). "Frances Monteith circa 1845-1898". Photographic History. Retrieved 7 May 2022.

- Wylie, James Aitken, ed. (1881). Disruption worthies : a memorial of 1843, with an historical sketch of the free church of Scotland from 1843 down to the present time. Edinburgh: T. C. Jack. pp. 413-418.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Biographical Index of Former Fellows of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 1783–2002. The Royal Society of Edinburgh. July 2006. p. 662. ISBN 0-902-198-84-X.