Alexander Gordon of Earlston

Sir Alexander Gordon of Earlston (1650–1726) was a 17th-century Scottish gentleman.[1] He was known as a Covenanter and was member of the United Societies network. He was involved in the early 1680s in fomenting rebellion against the Crown in Scotland.[2][3]

Sir Alexander Gordon of Earlston | |

|---|---|

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1650 |

| Died | 1726 |

| Denomination | Church of Scotland |

Life

Alexander Gordon was the son of William Gordon of Earlston, the correspondent of Samuel Rutherford, and brother of Sir William Gordon, 1st Baronet of Earlston.[3]

In 1679, his father was on his way to join the Covenanters at Bothwell Bridge when he was shot by a gang of English dragoons and flung into a ditch.[4] Alexander was in the army of the Covenanters at Bothwell Bridge, and narrowly escaped being taken by the ingenuity of one of his tenants, who recognizing him as he rode through Hamilton, made him dismount, hid his horse's furniture in a dunghill, dressed him in women's clothes, and set him to rock the cradle.[5]

For his participation in that conflict, Gordon was tried before the High Court of Justiciary on a charge of treason on 19 February 1680. He was found guilty and sentenced to death in absentia. He escaped capture for more than three years. On one occasion, in the dress of a servant, he helped the dragoons in searching the house for himself.[6] From 1682, Gordon was involved with John Nisbet in seeking support and financial assistance for the radical Covenanters, a group known as the United Societies.[7] They travelled together to London, and Gordon then went on his own to Holland.[3]

On 1 June 1683, Gordon embarked there for Holland with a person named Edward Aitken, and both were seized by some customs officers.[8] When they were about to set sail from Newcastle on covert business, Gordon and his servant were arrested. The pair tried to destroy papers by throwing them overboard, but they were recovered, and showed Gordon to be a conspirator. He was taken under guard to Edinburgh.[3] They were sent for trial to Edinburgh, where, on 10 July 1683, Aitken was condemned to death on the simple charge of harbouring Gordon.[9]

Trial and torture

A trial was thought superfluous, but Gordon was examined several times in reference to his knowledge of the Rye House plot. His depositions on these occasions, viz. 30 June, 5 July, and 25 September 1683, with Nisbet's letter, and his own commission from the ‘societies’ in Scotland, were printed at length by Thomas Sprat in his True Account of the Horrid Conspiracy against the late King.[10][6]

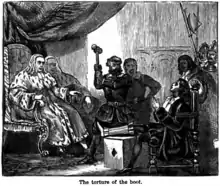

On 16 August, he had been brought to the bar of the justiciary court, and the sentence of death and forfeiture was passed upon him, and 28 September was fixed as the date of his execution. The King ordered the Privy Council of Scotland to put Gordon to the torture of the boots in order to extort from him the names of his accomplices. The council replied that it was irregular to torture malefactors after they had been condemned to death, but the King responded by sending Gordon on 11 September a reprieve till the second Friday of November.[6]

Gordon about this time made an ineffectual effort to escape. On 3 November, King Charles II extended the reprieve for a month, and a fortnight later again wrote ordering Gordon to be examined by torture. This command was immediately obeyed, but Gordon, on being brought to the council chamber on 23 November, either ‘through fear or distraction, roared out like a bull, and cried and struck about him so that the hangman and his man durst scarce lay hands on him,’ and at last fell down in a swoon. Upon recovering, he named several royalists as among the plotters, as some thought from madness or out of design. The Earl of Aberdeen, then chancellor, however, befriended him, and he was remitted to the care of the physicians. For greater quietness, they sent him to the castle of Edinburgh. On 13 December, his case was again before the council, when, as it was thought that the execution of a man in a state of insanity would endanger his soul, he was reprieved until the last Friday of January 1684.[6]

Gordon was brought again before the Lords of Justiciary, where the death sentence was ordered to be carried into effect. However, through the influence of a friend, the Duke of Gordon, his life was spared. Gordon was kept prisoner, and was interrogated on his knowledge of conspiracies under threat of torture. He was sent to the Bass Rock on 7 August 1684.[11] He was there until 22 August 1684, when he was transferred back to the Edinburgh Tolbooth by the Privy Council and not allowed to speak to anyone before he was shown to William Spence, another Scottish conspirator.[12][3] A resolution was taken by the council on this occasion ‘not to admit of his madness for an excuse, which they esteemed simulated.’ On the 30th he was again caught attempting to escape from the Tolbooth. The council debated whether on account of this aggravation of his crime the day fixed for his execution, 4 November, should not be anticipated. They found that the breaking of prison was not an offence punishable by death, and this could not legally be done; so on 20 September they ordered him to be removed to Blackness Castle.[6]

Imprisonment at Blackness Castle

.jpg.webp)

Thereafter Gordon was committed with Lady Gordon to the dungeons of Blackness Castle where he remained a prisoner until the Glorious Revolution brought his release.[14] Gordon's imprisonment in Blackness was voluntarily shared by his wife, and some of their children were born there. It continued until 5 June 1689, though on 16 August 1687, he was recommended to the King for a remission by the Scottish council. His employment during his confinement consisted in woodcarving and the study of heraldry. Some of the carvings were illustrations of events of his own times and family history.[6]

The Earlston estates were restored to Gordon after the revolution, and he and his family returned there from Blackness Castle. However, his losses were such that the estate had to be sold or heavily mortgaged. In February 1696, Gordon's wife died. Three covenant engagements into which she entered during her sojourn in Blackness Castle and her later life were printed after her death, entitled ‘Lady Earlston's Soliloquies.’[15] She and her husband both corresponded with the covenanting preachers James Renwick, Donald Cargill, and Richard Cameron; nine letters to them by those ministers were printed in a collection of Renwick's ‘Letters.’ Gordon remarried in 1697 to Marion, a daughter of Alexander, viscount Kenmure.[6]

In 1718, Gordon lost his younger brother, Sir William Gordon of Afton, who had distinguished himself in the Prussian army, had aided Monmouth, and had been made a Nova Scotia baronet on 29 July 1706 for his services to William III at the revolution. William Gordon seems to have redeemed Earlston from a family who had purchased it, as he obtained personal sasine in these lands in 1712. He died without issue, and both his title and his estates of Afton passed to his elder brother.[6]

Gordon died at Airds, near Castle Douglas, in Kirkcudbrightshire on 11 November 1726. He was buried in the churchyard of St John's Town of Dalry.[6]

Family

By his first wife he had thirteen children, and by the second two. His son Sir Thomas succeeded, and descendants of Gordon still live in Kirkcudbrightshire.[6][16]

Fiction

S.R. Crockett's Men of the Moss Hags tells the story of the Gordons of Earlstoun. Published in 12 serial instalments in Good Words Magazine, it was subsequently published by Isbister in 1895.[17] Alexander's brother William Gordon is the hero of the story. A sequel, Lochinvar was serialised in The Christian World Magazine and published by Methuen in 1897. Both novels were international bestsellers.[18]

Bibliography

- Lord Fountain halls Historical Notices of Scottish Affairs, 1661-8 (Bannatyne Club), i. 333–453, ii. 458-817

- Decisions, pp. 238–300

- McKerlie's History of the Lands and their Owners in Galloway, iii. 423–30, iv. 77.[6]

References

- Citations

- Sources

- Anderson, William (1877). "Gordon, of Earlston". The Scottish nation: or, The surnames, families, literature, honours, and biographical history of the people of Scotland. Vol. 2. A. Fullarton & co. pp. 325–326.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Crockett, S. R. (1895). The men of the moss-hags : being a history of adventure taken from the papers of William Gordon of Earlstoun in Galloway and told over again. London: Isbister & Co.

- "Dalry Covenanter Sculpture". Scottish Covenanter Memorials Association. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- Dickson, John (1899). Emeralds chased in Gold; or, the Islands of the Forth: their story, ancient and modern. [With illustrations.]. Edinburgh and London: Oliphant, Anderson & Ferrier. pp. 214–215.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Donaldson, Islay Murray (2016). Life and Work of S.R. Crockett. Ayton Publishing (2nd edition). ISBN 9781910601143.

- Fairley, John A. (1916). Extracts from the Records of the Old Tolbooth from The book of the Old Edinburgh Club. Vol. 9. Edinburgh: The Club. Retrieved 16 March 2019.

- Fountainhall, John Lauder, Lord (1837). Laing, David (ed.). Historical selections from the manuscripts of Sir John Lauder of Fountainhall. Edinburgh: Bannatyne Club. p. 96.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Greaves, Richard L. (2004). "Gordon, Alexander, of Earlston". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11019. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Mackenzie, William, of Galloway (1841). The history of Galloway, from the earliest period to the present time . Vol. 2. Kirkcudbright: J. Nicholson. pp. 248–252.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - M'Crie, Thomas (1847). The Bass rock: Its civil and ecclesiastic history. Edinburgh: J. Greig & Son. pp. 369–370.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - M'Kerlie, P. H. (1879). History of the lands and their owners in Galloway. Vol. 5. Edinburgh: William Paterson.

- Paton, Henry (1890). "Gordon, Alexander (1650-1726)". In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 22. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Porteous, James Moir (1881). The Scottish Patmos. A standing testimony to patriotic Christian devotion. Paisley: J. and R. Parlane. p. 74.

- Shields, Michael; Guthrie, James (1780). Faithful contendings displayed : being an historical relation of the state and actings of the suffering remnant in the church of Scotland, who subsisted in select societies, and were united in general correspondencies during the hottest time of the late persecution, viz. from the year 1681 to 1691 ... Glasgow: Printed by John Bryce. pp. 18–66.

- Sprat, Thomas (1685). A true account and declaration of the horrid conspiracy against the late king, His present Majesty, and the government: as it was order'd to be published by His late Majesty. Savoy, London: T. Newcomb. pp. 74–77, 91–109. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- Tweedie, William King, ed. (1845). Select biographies. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: Printed for the Wodrow Society.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Whyte, Alexander (1894). Samuel Rutherford and some of his correspondents; lectures delivered in St. George's Free Church Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier. p. 103.

- Wodrow, Robert (1829). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland from the restoration to the revolution, with an original memoir of the author, extracts from his correspondence, and preliminary dissertation and notes, in four volumes. Vol. 3. Glasgow: Blackie Fullerton & Co. p. 108, 470, 472.

- Wodrow, Robert (1835). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland from the restoration to the revolution, with an original memoir of the author, extracts from his correspondence, and preliminary dissertation and notes, in four volumes. Vol. 4. Glasgow: Blackie Fullerton & Co. pp. 502-503.