Alfred Wegener

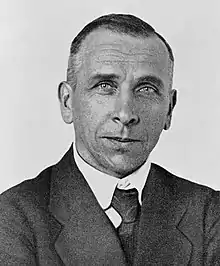

Alfred Lothar Wegener (/ˈveɪɡənər/;[1] German: [ˈʔalfʁeːt ˈveːɡənɐ];[2][3] 1 November 1880 – November 1930) was a German climatologist, geologist, geophysicist, meteorologist, and polar researcher.

Alfred Wegener | |

|---|---|

Wegener, c. 1924–1930 | |

| Born | Alfred Lothar Wegener 1 November 1880 |

| Died | November 1930 (aged 50) |

| Nationality | German |

| Citizenship | German |

| Alma mater | University of Berlin (PhD) |

| Known for | Continental drift theory |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Climatology, geology, geophysics, meteorology |

| Doctoral advisor | Julius Bauschinger |

| Signature | |

During his lifetime he was primarily known for his achievements in meteorology and as a pioneer of polar research, but today he is most remembered as the originator of continental drift hypothesis by suggesting in 1912 that the continents are slowly drifting around the Earth (German: Kontinentalverschiebung). His hypothesis was controversial and widely rejected by mainstream geology until the 1950s, when numerous discoveries such as palaeomagnetism provided strong support for continental drift, and thereby a substantial basis for today's model of plate tectonics.[4][5] Wegener was involved in several expeditions to Greenland to study polar air circulation before the existence of the jet stream was accepted. Expedition participants made many meteorological observations and were the first to overwinter on the inland Greenland ice sheet and the first to bore ice cores on a moving Arctic glacier.

Biography

Early life and education

Alfred Wegener was born in Berlin on 1 November 1880 as the youngest of five children in a clergyman's family. His father, Richard Wegener, was a theologian and teacher of classical languages at the Berlinisches Gymnasium zum Grauen Kloster. In 1886 his family purchased a former manor house near Rheinsberg, which they used as a vacation home. Today there is an Alfred Wegener Memorial site and tourist information office in a nearby building that was once the local schoolhouse.[6] He was cousin to film pioneer Paul Wegener.

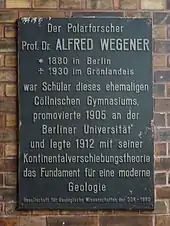

Wegener attended school at the Köllnisches Gymnasium on Wallstrasse in Berlin (a fact which is memorialised on a plaque on this protected building, now a school of music), graduating as the best in his class.

Wegener studied physics, meteorology and astronomy in Berlin, Heidelberg and Innsbruck. His teachers in Berlin included Wilhelm Foerster for astronomy, and Max Planck for thermodynamics.[7]

Wegener took away from Planck's teaching a strong commitment to brevity in the service of clarity. He adopted a caution, bordering on aloofness, in offering mechanical models and causal explanations, especially of the sort that only confirmed what one knew from experience without adding anything to the facts. [...] Most importantly, he heeded Planck's injunction never to consider any form of a theory as final, and to think of "good theory" simply as that mode of treating phenomena that corresponded to the actual state of a science at that moment—and never to one's aspirations for it.[7]

From 1902 to 1903 during his studies he was an assistant at the Urania astronomical observatory. He obtained a doctorate in astronomy in 1905 based on a dissertation written under the supervision of Julius Bauschinger at Friedrich Wilhelms University (today Humboldt University), Berlin. Wegener had always maintained a strong interest in the developing fields of meteorology and climatology and his studies afterwards focused on these disciplines.

In 1905 Wegener became an assistant at the Aeronautisches Observatorium Lindenberg near Beeskow. He worked there with his brother Kurt, two years his senior, who was likewise a scientist with an interest in meteorology and polar research. The two pioneered the use of weather balloons to track air masses. On a balloon ascent undertaken to carry out meteorological investigations and to test a celestial navigation method using a particular type of quadrant ("Libellenquadrant"), the Wegener brothers set a new record for a continuous balloon flight, remaining aloft 52.5 hours from 5–7 April 1906.[8]

First Greenland expedition and years in Marburg

In that same year 1906, Wegener participated in the first of his four Greenland expeditions, later regarding this experience as marking a decisive turning point in his life. The Denmark expedition was led by the Dane Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen and charged with studying the last unknown portion of the northeastern coast of Greenland. During the expedition Wegener constructed the first meteorological station in Greenland near Danmarkshavn, where he launched kites and tethered balloons to make meteorological measurements in an Arctic climatic zone. Here Wegener also made his first acquaintance with death in a wilderness of ice when the expedition leader and two of his colleagues died on an exploratory trip undertaken with sled dogs.

After his return in 1908 and until World War I, Wegener was a lecturer in meteorology, applied astronomy and cosmic physics at the University of Marburg. His students and colleagues in Marburg particularly valued his ability to clearly and understandably explain even complex topics and current research findings without sacrificing precision. His lectures formed the basis of what was to become a standard textbook in meteorology, first written In 1909/1910: Thermodynamik der Atmosphäre (Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere), in which he incorporated many of the results of the Greenland expedition.

On 6 January 1912 he presented his first proposal of continental drift in a lecture to the Geologischen Vereinigung at the Senckenberg Museum, Frankfurt am Main. Later in 1912 he made the case for the theory in a long, three-part article[9] and a shorter summary.[10]

Second Greenland expedition

Plans for a new Greenland expedition grew out of Wegener and Johan Peter Koch's frustration with the disorganisation and meager scientific results of the Danmark expedition. The new Danish Expedition to Queen Louise Land would involve only four men, take place in 1912–1913, and have Koch for leader.[7]

After a stopover in Iceland to purchase and test ponies as pack animals, the expedition arrived in Danmarkshavn. Even before the trip to the inland ice began the expedition was almost annihilated by a calving glacier. Koch broke his leg when he fell into a glacier crevasse and spent months recovering in a sickbed. Wegener and Koch were the first to winter on the inland ice in northeast Greenland.[11] Inside their hut they drilled to a depth of 25 m with an auger. In summer 1913 the team crossed the inland ice, the four expedition participants covering a distance twice as long as Fridtjof Nansen's southern Greenland crossing in 1888. Only a few kilometres from the western Greenland settlement of Kangersuatsiaq the small team ran out of food while struggling to find their way through difficult glacial break-up terrain. But at the last moment, after the last pony and dog had been eaten, they were picked up at a fjord by the clergyman of Upernavik, who just happened to be visiting a remote congregation at the time.

Family

Later in 1913, after his return Wegener married Else Köppen, the daughter of his former teacher and mentor, the meteorologist Wladimir Köppen. The young pair lived in Marburg, where Wegener resumed his university lectureship. There his two older daughters were born, Hilde (1914–1936) and Sophie ("Käte", 1918–2012). Their third daughter Hanna Charlotte ("Lotte", 1920–1989) was born in Hamburg. Lotte would in 1938 marry the famous Austrian mountaineer and adventurer Heinrich Harrer, while in 1939, Käte married Siegfried Uiberreither, Austrian Nazi Gauleiter of Styria.[12]

World War I

As an infantry reserve officer Wegener was immediately called up when the First World War began in 1914. On the war front in Belgium he experienced fierce fighting but his term lasted only a few months: after being wounded twice he was declared unfit for active service and assigned to the army weather service. This activity required him to travel constantly between various weather stations in Germany, on the Balkans, on the Western Front and in the Baltic region.

Nevertheless, he was able in 1915 to complete the first version of his major work, Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane ("The Origin of Continents and Oceans"). His brother Kurt remarked that Alfred Wegener's motivation was to "reestablish the connection between geophysics on the one hand and geography and geology on the other, which had become completely ruptured because of the specialized development of these branches of science."

Interest in this small publication was however low, also because of wartime chaos. By the end of the war Wegener had published almost 20 additional meteorological and geophysical papers in which he repeatedly embarked for new scientific frontiers. In 1917 he undertook a scientific investigation of the Treysa meteorite.

Postwar period

In 1919, Wegener replaced Köppen as head of the Meteorological Department at the German Naval Observatory (Deutsche Seewarte) and moved to Hamburg with his wife and their two daughters.[7] In 1921 he was moreover appointed senior lecturer at the new University of Hamburg. From 1919 to 1923 Wegener did pioneering work on reconstructing the climate of past eras (now known as "paleoclimatology"), closely in collaboration with Milutin Milanković,[13] publishing Die Klimate der geologischen Vorzeit ("The Climates of the Geological Past") together with his father-in-law, Wladimir Köppen, in 1924.[14] In 1922 the third, fully revised edition of "The Origin of Continents and Oceans" appeared, and discussion began on his theory of continental drift, first in the German language area and later internationally. Withering criticism was the response of most experts.

In 1924 Wegener was appointed to a professorship in meteorology and geophysics in Graz, a position that was both secure and free of administrative duties.[7] He concentrated on physics and the optics of the atmosphere as well as the study of tornadoes. He had studied tornadoes for several years by this point, publishing the first thorough European tornado climatology in 1917. He also posited tornado vortex structures and formative processes.[15] Scientific assessment of his second Greenland expedition (ice measurements, atmospheric optics, etc.) continued to the end of the 1920s.

In November 1926 Wegener presented his continental drift theory at a symposium of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists in New York City, again earning rejection from everyone but the chairman. Three years later the fourth and final expanded edition of "The Origin of Continents and Oceans" appeared.

Third and fourth Greenland expeditions

In April–October 1929, Wegener embarked on his third expedition to Greenland, which laid the groundwork for the main expedition which he was planning to lead in 1930–1931.

Wegener's last Greenland expedition was in 1930. The 14 participants under his leadership were to establish three permanent stations from which the thickness of the Greenland ice sheet could be measured and year-round Arctic weather observations made. They would travel on the ice cap using two innovative, propeller-driven snowmobiles, in addition to ponies and dog sleds. Wegener felt personally responsible for the expedition's success, as the German government had contributed $120,000 ($1.5 million in 2007 dollars). Success depended on enough provisions being transferred from West camp to Eismitte ("mid-ice") for two men to winter there, and this was a factor in the decision that led to his death. Owing to a late thaw, the expedition was six weeks behind schedule and, as summer ended, the men at Eismitte sent a message that they had insufficient fuel and so would return on 20 October.

On 24 September, although the route markers were by now largely buried under snow, Wegener set out with thirteen Greenlanders and his meteorologist Fritz Loewe to supply the camp by dog sled. During the journey, the temperature reached −60 °C (−76 °F) and Loewe's toes became so frostbitten they had to be amputated with a penknife without anaesthetic. Twelve of the Greenlanders returned to West camp. On 19 October the remaining three members of the expedition reached Eismitte.

Expedition member Johannes Georgi estimated that there were only enough supplies for three at Eismitte, so Wegener and Rasmus Villumsen took two dog sleds and made for West camp. (Georgi later found that he had underestimated the supplies, and that Wegener and Villumsen could have overwintered at Eismitte.[7]) They took no food for the dogs and killed them one by one to feed the rest until they could run only one sled. While Villumsen rode the sled, Wegener had to use skis, but they never reached the camp: Wegener died and Villumsen was never seen again. After Wegener was declared missing in May 1931, and his body found shortly thereafter, Kurt Wegener took over the expedition's leadership in July, according to the prearranged plan for such an eventuality.[7]

This expedition inspired the Greenland expedition episode of Adam Melfort in John Buchan's 1933 novel A Prince of the Captivity.

Death

Wegener died in Greenland in around the middle of November 1930 while returning from an expedition to bring food to a group of researchers camped in the middle of an icecap.[16] He supplied the camp successfully, but there was not enough food at the camp for him to stay there. He and a colleague, Rasmus Villumsen, took dog sleds to travel to another camp – which they never reached. Villumsen buried Wegener's body with great care, a pair of skis marking the grave site. After burying Wegener, Villumsen resumed his journey to West camp, but he was never seen again. Six months later, on 12 May 1931, the grave was discovered halfway between Eismitte and West camp. Expedition members built a pyramid-shaped mausoleum in the ice and snow, and Alfred Wegener's body was laid to rest in it.[17] Wegener had been 50 years of age and a heavy smoker, and it was believed that he had died of heart failure brought on by overexertion. Villumsen was 23 when he died, and it is estimated that his body, and Wegener's diary, now lie under more than 100 metres (330 ft) of accumulated ice and snow.

Continental drift theory

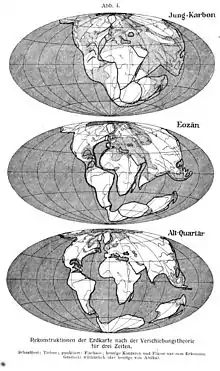

Alfred Wegener first thought of this idea by noticing that the different large landmasses of the Earth almost fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. The continental shelf of the Americas fits closely to Africa and Europe. Antarctica, Australia, India and Madagascar fit next to the tip of Southern Africa. But Wegener only published his idea after reading a paper in 1911 which criticised the prevalent hypothesis, that a bridge of land once connected Europe and America, on the grounds that this contradicts isostasy.[18] Wegener's main interest was meteorology, and he wanted to join the Denmark-Greenland expedition scheduled for mid-1912. He presented his Continental Drift hypothesis on 6 January 1912. He analysed both sides of the Atlantic Ocean for rock type, geological structures and fossils. He noticed that there was a significant similarity between matching sides of the continents, especially in fossil plants.

From 1912, Wegener publicly advocated the existence of "continental drift", arguing that all the continents were once joined in a single landmass and had since drifted apart. He supposed that the mechanisms causing the drift might be the centrifugal force of the Earth's rotation ("Polflucht") or the astronomical precession. Wegener also speculated about sea-floor spreading and the role of the mid-ocean ridges, stating that "the Mid-Atlantic Ridge ... zone in which the floor of the Atlantic, as it keeps spreading, is continuously tearing open and making space for fresh, relatively fluid and hot sima [rising] from depth."[19] However, he did not pursue these ideas in his later works.

In 1915, in the first edition of his book, Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane, written in German,[20] Wegener drew together evidence from various fields to advance the theory that there had once been a giant continent, which he named "Urkontinent"[21] (German for "primal continent", analogous to the Greek "Pangaea",[22] meaning "All-Lands" or "All-Earth"). Expanded editions during the 1920s presented further evidence. (The first English edition was published in 1924 as The Origin of Continents and Oceans, a translation of the 1922 third German edition.) The last German edition, published in 1929, revealed the significant observation that shallower oceans were geologically younger. It was, however, not translated into English until 1962.[20]

Reaction

In his work, Wegener presented a large amount of observational evidence in support of continental drift, but the mechanism remained a problem, partly because Wegener's estimate of the velocity of continental motion, 250 cm/year, was too high.[23] (The currently accepted rate for the separation of the Americas from Europe and Africa is about 2.5 cm/year.)[24]

While his ideas attracted a few early supporters such as Alexander Du Toit from South Africa, Arthur Holmes in England [25] and Milutin Milanković in Serbia, for whom continental drift theory was the premise for investigating polar wandering,[26][27] the hypothesis was initially met with scepticism from geologists, who viewed Wegener as an outsider and were resistant to change.[25] Nevertheless, the eminent Swiss geologist Émile Argand advocated Wegener's theory in his inaugural address to the 1922 International Geological Congress.[7]

The one American edition of Wegener's work, published in 1925, was written in "a dogmatic style that often results from German translations".[25] In 1926, at the initiative of Willem van der Gracht, the American Association of Petroleum Geologists organised a symposium on the continental drift hypothesis.[28][7] The opponents argued, as did the Leipziger geologist Franz Kossmat, that the oceanic crust was too firm for the continents to "simply plough through".

From at least 1910, Wegener imagined the continents once fitting together not at the current shore line, but 200 m below this, at the level of the continental shelves, where they match well.[25] Part of the reason Wegener's ideas were not initially accepted was the misapprehension that he was suggesting the continents had fit along the current coastline.[25] Charles Schuchert commented:

During this vast time [of the split of Pangea] the sea waves have been continuously pounding against Africa and Brazil and in many places rivers have been bringing into the ocean great amounts of eroded material, yet everywhere the geographic shore lines are said to have remained practically unchanged! It apparently makes no difference to Wegener how hard or how soft are the rocks of these shore lines, what are their geological structures that might aid or retard land or marine erosion, how often the strand lines have been elevated or depressed, and how far peneplanation has gone on during each period of continental stability. Furthermore, sea-level in itself has not been constant, especially during the Pleistocene, when the lands were covered by millions of square miles of ice made from water subtracted out of the oceans. In the equatorial regions, this level fluctuated three times during the Pleistocene, and during each period of ice accumulation the sea-level sank about 250 feet [75 m].

Wegener was in the audience for this lecture, but made no attempt to defend his work, possibly because of an inadequate command of the English language.

In 1943, George Gaylord Simpson wrote a strong critique of the theory (as well as the rival theory of sunken land bridges) and gave evidence for the idea that similarities of flora and fauna between the continents could best be explained by these being fixed land masses which over time were connected and disconnected by periodic flooding, a theory known as permanentism.[29] Alexander du Toit wrote a rejoinder to this the following year.[30]

Alfred Wegener has been mischaracterised as a lone genius whose theory of continental drift met widespread rejection until well after his death. In fact, the main tenets of the theory gained widespread acceptance by European researchers already in the 1920s, and the debates were mostly about specific details. However, the theory took longer to be accepted in North America.[7]

Modern developments

In the early 1950s, the new science of paleomagnetism pioneered at the University of Cambridge by S. K. Runcorn and at Imperial College by P.M.S. Blackett was soon producing data in favour of Wegener's theory. By early 1953 samples taken from India showed that the country had previously been in the Southern hemisphere as predicted by Wegener. By 1959, the theory had enough supporting data that minds were starting to change, particularly in the United Kingdom where, in 1964, the Royal Society held a symposium on the subject.[31]

The 1960s saw several relevant developments in geology, notably the discoveries of seafloor spreading and Wadati–Benioff zones, and this led to the rapid resurrection of the continental drift hypothesis in the form of its direct descendant, the theory of plate tectonics. Maps of the geomorphology of the ocean floors created by Marie Tharp in cooperation with Bruce Heezen were an important contribution to the paradigm shift that was starting. Wegener was then recognised as the founding father of one of the major scientific revolutions of the 20th century.

With the advent of the Global Positioning System (GPS) in 1993, it became possible to measure continental drift directly.[32]

Awards and honours

The Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Bremerhaven, Germany, was established in 1980 on Wegener's centenary. It awards the Wegener Medal in his name.[33] The crater Wegener on the Moon and the crater Wegener on Mars, as well as the asteroid 29227 Wegener, the Wegener Peninsula in Eastern Greenland and the peninsula where he died in Western Greenland near Ummannaq, 71°12′N 51°50′W, are named after him.[34]

The European Geosciences Union sponsors an Alfred Wegener Medal & Honorary Membership "for scientists who have achieved exceptional international standing in atmospheric, hydrological or ocean sciences, defined in their widest senses, for their merit and their scientific achievements."[35]

Selected works

- Wegener, Alfred (1911). Thermodynamik der Atmosphäre [Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere] (in German). Leipzig: Verlag Von Johann Ambrosius Barth.

- Wegener, Alfred (1912). "Die Herausbildung der Grossformen der Erdrinde (Kontinente und Ozeane), auf geophysikalischer Grundlage". Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen (in German). 63: 185–195, 253–256, 305–309. (Presented at the annual meeting of the German Geological Society, Frankfurt am Main, 6 January 1912).

- Wegener, Alfred (July 1912). "Die Entstehung der Kontinente". Geologische Rundschau (in German). 3 (4): 276–292. Bibcode:1912GeoRu...3..276W. doi:10.1007/BF02202896. S2CID 129316588.

- Wegener, Alfred (1922). Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane [The Origin of Continents and Oceans] (in German). ISBN 3-443-01056-3. LCCN unk83068007.

- Wegener, Alfred (1929). Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane [The Origin of Continents and Oceans] (in German) (4th ed.). Braunschweig: Friedrich Vieweg & Sohn Akt. Ges. ISBN 3-443-01056-3.

- English language edition: Wegener, Alfred (1966). The Origin of Continents and Oceans. Translated by John Biram, from the fourth revised German edition. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-61708-4. British edition: Methuen, London (1968).

- Köppen, W. & Wegener, A. (1924): Die Klimate der geologischen Vorzeit, Borntraeger Science Publishers. English language edition: The Climates of the Geological Past 2015.

- Wegener, Elsie; Loewe, Fritz, eds. (1939). Greenland Journey, The Story of Wegener's German Expedition to Greenland in 1930–31 as told by Members of the Expedition and the Leader's Diary. Translated by Winifred M. Deans, from the seventh German edition. London: Blackie & Son Ltd.

See also

- Hair ice – Wegener introduced a theory on the growth of hair ice in 1918.

References

- "Wegener" Archived 29 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- Dudenredaktion; Kleiner, Stefan; Knöbl, Ralf (2015) [First published 1962]. Das Aussprachewörterbuch [The Pronunciation Dictionary] (in German) (7th ed.). Berlin: Dudenverlag. pp. 177, 897. ISBN 978-3-411-04067-4.

- Krech, Eva-Maria; Stock, Eberhard; Hirschfeld, Ursula; Anders, Lutz Christian (2009). Deutsches Aussprachewörterbuch [German Pronunciation Dictionary] (in German). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 302, 1047. ISBN 978-3-11-018202-6.

- Spaulding, Nancy E.; Namowitz, Samuel N. (2005). Earth Science. Boston: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-618-11550-1.

- McIntyre, Michael; Eilers, H. Peter; Mairs, John (1991). Physical geography. New York: Wiley. p. 273. ISBN 0-471-62017-3.

- The memorial site is the Gedenkstätte Zechlinerhütte, see "Zechlinerhütte - Alfred Wegener Gedenkstätte". Archived from the original on 2 July 2012. Retrieved 18 April 2012. (in German)

- Greene, Mott T. (15 October 2018). Alfred Wegener : science, exploration, and the theory of continental drift. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-2709-6. OCLC 1030902106.

- Victor Silberer: Die Dauerfahrt von 52½ Stunden. In: Wiener Luftschiffer-Zeitung 5, Heft 8, 1906, S. 156–157

- Wegener, Alfred (1912). "Die Entstehung der Kontinente". Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen aus Justus Perthes' geographischer Anstalt. 58: 185–195, 253–256, 305–309 – via The journals@UrMEL portal operated by the Thuringian University and State Library Jena (ThULB).

- Wegener, Alfred (1 July 1912). "Die Entstehung der Kontinente". Geologische Rundschau (in German). 3 (4): 276–292. Bibcode:1912GeoRu...3..276W. doi:10.1007/BF02202896. ISSN 1432-1149. S2CID 129316588.

- Dansgaard W (2004). Frozen Annals Greenland Ice Sheet Research. Odder, Denmark: Narayana Press. p. 124. ISBN 87-990078-0-0.

- Michaël Stürm, Account of Uiberreither postwar incognito life Archived 10 May 2019 at the Wayback Machine, in Stadt und Kreis Böbblingen, 21 February 2017

- introduction to the English edition, The Climates of the Geological Past, (2015), retrieved 28 August 2015

- Köppen, W. & Wegener, A. (1924): Die Klimate der geologischen Vorzeit, Borntraeger Science Publishers. In English as The Climates of the Geological Past (2015).

- Antonescu, Bogdan; H. M. A. M. Ricketts; D. M. Schultz (2019). "100 Years Later: Reflecting on Alfred Wegener's Contributions to Tornado Research in Europe". Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 100 (4): 567–578. Bibcode:2019BAMS..100..567A. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-17-0316.1. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- "Alfred Wegener (1880-1930)". University of California Museum of Paleontology. Archived from the original on 26 September 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Alfred Wegener - Biography, Facts and Pictures". famousscientists.org. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Arldt, Th. (1910). "Referat Scharff: Ueber die Beweissgruende fuer eine fruehere Landbruecke zwischen Nordeuropa und Nordamerika". Naturwiss. Rdsch. (in German). 25: 86–87., Scharff, R. F. (1909). "Ueber die Beweissgruende fuer eine fruehere Landbruecke zwischen Nordeuropa und Nordamerika". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy (in German). 28: 1–28. cited in Flügel, Helmut W. (December 1980). "Wegener-Ampferer-Schwinner: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Geologie in Österreich" [Wegener-Ampferer-Schwinner: A Contribution to the History of the Geology in Austria] (PDF). Mitt. österr. Geol. Ges. (in German). 73. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2010.

- Jacoby, W. R. (January 1981). "Modern concepts of earth dynamics anticipated by Alfred Wegener in 1912". Geology. 9 (1): 25–27. Bibcode:1981Geo.....9...25J. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1981)9<25:MCOEDA>2.0.CO;2.

- Frankel, Henry R. (2012). The Continental Drift Controversy: Volume 1, Wegener and the Early Debate. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 152, 584. ISBN 978-0-521-87504-2.

- According to the OED, 2d edition (1989), the word is not found in the 1915 edition of Wegener's text; it appears in the 1920 edition but with no indication that Wegener coined it.

- W.A.J.M. van Waterschoot van der Gracht; Bailey Willis; Rollin T. Chamberlin; et al. (1928). W.A.J.M. van Waterschoot van der Gracht (ed.). Theory of Continental Drift: a symposium on the origin and movement of land masses both intercontinental and intracontinental as proposed by Alfred Wegener, A Symposium of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG, 1926). Tulsa, Okla. p. 240.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - University of California Museum of Paleontology, Alfred Wegener (1880–1930) Archived 8 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 30 April 2015).

- Unavco Plate Motion Calculator Archived 25 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine (accessed 30 April 2015).

- Drake, Ellen T. (1 January 1976). "Alfred Wegener's reconstruction of Pangea". Geology. 4 (1): 41. Bibcode:1976Geo.....4...41D. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1976)4<41:AWROP>2.0.CO;2.

- Mathematische Klimalehre und astronomische Theorie der Klimaschwankungen. in W. Köppen & R. Geiger (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Klimatologie Bd. 1: Allgemeine Klimalehre. Borntraeger, Berlin, 1930

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - H. Tristam Engelhardt Jr; Arthur L. Caplan, eds. (1987). Scientific Controversies: Case studies in the resolution and closure of disputes in science and technology. pp. 210–211.

- Simpson, G.G. (1943). "Mammals and the Nature of Continents". American Journal of Science. 241 (1): 1–31. Bibcode:1943AmJS..241....1S. doi:10.2475/ajs.241.1.1. Archived from the original on 29 July 2017. Retrieved 29 July 2017.

- du Toit, A. (1944). "Tertiary Mammals and Continental Drift". American Journal of Science. 242 (3): 145–63. Bibcode:1944AmJS..242..145D. doi:10.2475/ajs.242.3.145.

- Frankel, H. (1987). "The Continental Drift Debate". In H.T. Engelhardt Jr and A.L. Caplan (ed.). Scientific Controversies: Case Solutions in the resolution and closure of disputes in science and technology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27560-6.

- Brady Haran (4 June 2003). "The millimetre men". BBC News UK. Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- "2005 Annual report" Archived 30 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, page 259, Alfred Wegener Institute

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser". Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- "EGU: Awards & Medals". Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2009.

External links

- Works by Alfred Wegener at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Alfred Wegener at Internet Archive

- Works by Alfred Wegener at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Wegener Institute website

- USGS biography of Wegener

- Wegener biography at Pangaea.org

- Alfred Wegener (1880–1930) – Biographical material

- Wegener's paper (1912) online and analysed, BibNum (for English text go to "A télécharger")

- Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane – full digital facsimile at Linda Hall Library

- Newspaper clippings about Alfred Wegener in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW