All-Asian Women's Conference

The All-Asian Women's Conference (AAWC) was a women's conference convened in Lahore in January 1931. It was the first pan-Asian women's conference of its kind.[1] Dominated by Indian organizers, "the AAWC was a vehicle for Indian women to voice their ideas and vision of an Indian-centred Asia".[2] Its predecessor, the All Indian Women's Conference (AIWC), aimed to examine areas of education and legislation to improve the position of women.[3] Like the AIWC, the AAWC aimed to expand this agenda in order to include women in Asia's vision for independence.

Background

Margaret Cousins and the Indian activists who had taken part in the 1927 All Indian Women's Conference were the minds behind the AAWC. Upon moving to India with her husband, Margaret Cousins became involved with social reform on the position of women in India.[2] Her inspiration for founding the AAWC was ignited by her visit to Hawaii in 1928 at the Pan-Pacific Women's Conference, which had resulted in the foundation of the Pan-Pacific Women's Association. The motives behind the conference were the lack of focus on feminism within the Pan-Asian context.[2] and also supported the right to self-determination, as many delegates were involved with their country's independence movements.[4] This took place in a broader global context of new internationalism within the interwar period. The early 1930s saw other non-Western feminist regional cooperation, such as the Pan-Pacific Women's Association, Inter-American Commission of Women and All Indian Women's Conference.[4]

The conference was chosen to take place in Lahore to allow the delegates to sightsee in nearby Agra and Delhi.[1] Circular invitations among Indian women for the AAWC were sent on March 12, 1930, to suggest that the conference take place in January 1931.[2] Invited delegates included Sarojini Naidu, Muthulakshmi Reddi, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Lady Abdul Qadir, Rani Lakshmibai Rajwade and Hilla Rustomji Faridoonji. These women were mostly past delegates of the All-Indian Women's Conference and dedicated social activists to women's issues.The date was picked to strategically take place in between "two of the Pan-Pacific Women's Conferences planned for Hawaii in August 1930 and China in 1932".[2] After creating the grounds for the conference, Cousins took a step back to let the Indian women "preside over the organisation" of the conference.[2]

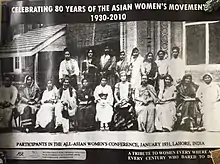

Thirty Asian countries were invited to the AAWC, including Georgia, Palestine, Iraq, Syria, Malaya, Indo-China, Siam and Hawaii.[1] There were a total of 36 delegates present: 19 from the 30 Asian countries invited and 17 Indian delegates, as well as nine foreign visitors, including Margaret Cousins. These delegates were ready to begin a discourse on women roles in social and political issues.[1] Some of these issues were reflected in the recommendations made from the All Indian Women's Conference, such as the need to have a larger number of seats reserved for Indian women graduates on the senates of all Indian universities.[3] Sarajoni Naidu was initially voted as President of the Conference and is well known for her friendship with Mahatma Gandhi. Naidu, however, was arrested in May 1930 for her "role in the Indian nationalist civil disobedience movement."[2] As a result, each session of the conference was presided over by different Presidents. These Presidents included Sirimavo Bandaranaike from Ceylon, Mrs. Kamal-ud-din from Afghanistan, Daw Mya Sein from Burma, Shirin Fozdar from Persia and Miss Hoshi from Japan.[2]

The Rani of Mandi, daughter to ruler the Maharani of Kapurthala, laid the groundwork for the conference in her opening speech, as quoted below:

"Living practically under identical conditions, sharing the good or ill effects of similar customs and traditions and cramped psychology, and actuated in an equal measure by a longing for a change for what may be described as the renaissance of the women of Asia, no organization existed for them to come together, to exchange ideas and devise measures for achieving their common aims and objects. This Conference, I need scarcely point out, is designed to provide such a medium, a nucleus for the regeneration of our womankind on an intellectual bias."[5]

Participants

In the early months of 1930, circular invitations for the All Asian Women Conference were sent to more than 300 country representatives, women's rights organizations and activists in thirty-three countries.[5] Countries such as Georgia, Palestine, Iraq, Syria as well as Malaya, Indo-China, Siam, and Hawaii were invited. However, only nineteen delegates from these invitations participated, representing Afghanistan, Burma, Ceylon, Japan, Persia and Iraq.[2] Delegates from countries such as Palestine, Pakistan, Russia, Nepal, and Syria completed the registration to attend but withdrew prior to the conference for multiple reasons such as illness, conflicts in schedules and denied visas. In addition, two delegates from Java participated at the conference as visitors after withdrawing their status as delegates. In addition to the government representatives and organizations, private individuals were also able to register for the conference as either delegates or visitors. Moreover, non-Asian women from countries such as the United States, New Zealand, Ireland, and Great Britain were also present as visitors.

Key Figures and their Roles

Margaret Cousins

Margaret Cousins was one of the key driving forces and organizers of the first All-Asian Women conference. She was a member of the Irish Suffrage Movement and therefore, developed a strong passion for social reform and improving the position of Indian women after moving to India in 1915. In the late 1910s and 1920s, she was involved in movements and campaigns for women's rights such as demanding equal suffrage rights for women.[2]

After participating in the 1928 Pan-Pacific Women's Association (PPWA) conference in Hawaii, Cousins got the inspiration for organizing a similar conference for solidarity among women in Asia. Cousins believed that there was a lack of spiritual consciousness and a need for preservation of the "oriental" qualities of Asia and therefore Asian women must meet to become self-conscious. She started sending out letters in December 1929 to propose her idea and persuade other women from India and various other parts of Asia to join her. In her letters, she proposed that Indian women take the lead for this conference as they had already had an experience with the All-Indian Women conference. Although she was the prominent figure for initiating the AAWC, she wanted the Asian women, mainly Indian women, to take charge and further supervise the organization.

Rameshwari Nehru

Rameshwari Nehru was a women's rights activist and spent her early career as a social reformer. After hearing about the AAWC, she became very active at the conference and its organization. After attending the conference, Nehru became one of the founders of a Permanent Committee and aimed to continue organizing Asian Women's Conferences in the future. This committee, however, disbanded soon after and remained inactive until Nehru's Asianist activities in the 1950s.[6]

May Oung

May Oung, also known as Daw Mya Sein, attended the AAWC at Lahore to represent Burma and presided over a session.[1] Oung was appointed secretary of the Liaison Committee at the AAWC and was on the committee from 1931 to 1933.[2] She previously had the experience of being an executive of the National Council of Women in India as their Burmese member.[1] In July 1931, Margaret Cousins selected her to represent the AAWC at the League of Nations on a Women's Consultative Committee on Nationality.[2]

Sarojini Naidu

Sarojini Naidu was a very active women's rights advocate and social reformer. After a postal vote, she was appointed as the President of the All-Asian Women Conference. Before the conference, however, she was sent to jail in May 1930 for her role in Salt March, the Indian Nationalist Civil Disobedience Movement. In the absence of Sarojini Naidu, Bandaranaike (Ceylon), Kamal-ud-din (Afghanistan), Oung (Burma), Fozdar (Persia) and Hoshi (Japan) presided over events in addition to two Indian women, Muthulakshmi Reddi and Shareefah Hamid Ali.

Conference Objectives

Prior to the conference, the transnational and global organizing of women mainly focused on Euro-American-centric organizations.[2] There was no organization that provided room for Asian women from different countries to convene and discuss means of achieving common aims and objectives, despite having similar social contexts.[5] Established political groupings made it such that interactions between Asian women and Asian cultures were limited. The East-West (colonized-colonizer) relationship transcended as the main means of sharing information.[5] The AAWC placed the feminist conversation within a pan-Asian context, moving it away from western centers.[2] They had an aim of changing the discourse regarding Asian womanhood and recreating images of "the Orient" by creating a "counterdiscourse to the feminist Orientalist."[5]

The conference had 6 main objectives which sought to:

- "To promote the consciousness of unity amongst the women of Asia, as members of a common Oriental culture,

- "To take stock of the qualities of Oriental civilization so as to preserve them for national and world service,

- "To review and seek remedies for the defects at present apparent in Oriental civilization,

- "...sift[ing] what is appropriate for Asia from the Occidental influences,

- "To strengthen one another by exchange of data and experiences concerning women's conditions in the respective countries of Asia,

- "To achieve world peace."[5]

The first three objectives closely mirrored the pan-Asian vision promoted by Rabindranath Tagore during his travels to the United States and Asia.[5] Tagore wrote a letter to the All-Asian Women's Conference, highlighting the importance of having women bring Asia to the world and aid in enriching world culture through the "consolidation of the cultural consciousness of the Orient."[5] The speakers at the conference highlighted the preconceived ideas of what constitutes as Asian womanhood such as peacefulness, devotion to one's family, obedience and so forth.[5] To move away from these domestic characteristics, the achievements of Asian women outside the submissive household context were greatly highlighted.[5] Many of the conference attendees viewed patriarchy to be the root cause of the oppression of women. Hence, applause was given to women who had better status than men in the society, were in charge of decision making, had the ability divorce men etc.

The last three objectives sought to highlight the positioning of Asian women internationally. Some delegates criticized the influence of Western ideas on their societies and argued that Western attitudes undermined Middle Eastern and Asian cultural values.[4] This highlighted the detachment that some of these Asian feminists felt from their Western counterparts. Other delegates, however, saw utility in not completely rejecting Western influence, but rather, choosing based on what fit the Asian, such as dressing, Western education and even cinema.[2] The importance of the collection of data on the political, economical and religious statuses of women was also emphasized.[5] This would allow for the cross-referencing of women's conditions worldwide. The last objective was common across all women's organizations across the world, such as the International Council of Women and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.[5] The promotion of world peace became important for many women's organizations during the First World War, the interwar period and the Second World War. This responsibility was extended to Asia with it being a "continent renowned for its love and peace."[5] There was a general consensus among the conference participants that asserting an Asian identity and adopting the notion of Asian sisterhood did not depend on them giving up their national identity.[2]

Reactions

The conference was highlighted on a number of media platforms both in India and internationally. The American women's paper, Equal Rights, stated that it was "attended by outstanding women from every country in Asia", however, failed to emphasize the fact that it lacked equal representation.[2] They also reported that there is a "striking similarity" in the problems that "confront the women in the East and the West."[2]

The Indian Magazine and Review, edited by Jessie Duncan Westbrook for the National Indian Association, a British organization for people interested in India, supported the conference by having its preview inspired by the circular of invitation of AAWC. It focused on the term 'Oriental Women' and said that it was inspired by various western relationships. It also suggested that the women of Asia should continue to meet together to discuss their unique problems and by recognizing their "fundamental difference from women of other lands", should come to solve their difficulties.[2] The editor of L'Oeuvre and Pax International also reported the conference after it took place.[5]

AAWC also received support from a number of Western organizations. This included the League of Nations, the Whitley Labour Commission, the Women's International Council (London Branch), New Zealand and Indian Welfare League.[5]

The conference also gained acknowledgment and applause from men around the globe as well as the host nation. For instance, Sir Abdul Qadir, who was a guest at the conference, remarked it as "an epoch-making event."[5] Honourable Sadar Sir Jogendra Singh, the Minister of Agriculture, expressed "I know of no parallel in the history of the world of such a movement as this Women's Conference representing the whole of Asia."[4]

The focus of the conference was also recognized and adopted by Jawaharlal Nehru in his nation building policies. He believed in the common Asian history of civilization and embraced in his actions towards his objective of establishing India as the new center of pan-Asian unity.[5]

Outcomes and Accomplishments

AAWC aimed to discuss the common social and political concerns of women in Asia as well as speak about the visions of pan-Asianism. The conference was proud to have had Indian women play the central role of drawing Asian women together.[4] It was not aimed to be political.[2] With the initiative, the conference organizers also received letters from a variety of women nationalists, feminist activists and social workers who were keen to attend, including Madam Mahomed Jamil Begum from Syria, Madame Nour Hamad the President of the Women's Arabian Conference, the Palestine Jewish Women's Equal Rights Association, the Nepali Ladies' Association.[5]

AAWC was successful in passing a main resolution, which sought to gain support for the reform for equality of nationality rights for married women. At the time, there was no uniform international law regarding the nationality of married women. Some women would gain the nationality of their husbands, while others would not, thus finding themselves without any citizenship from either birth or marriage. The support pushed to allow a woman to choose her nationality. This resolution also helped Asian women to gain recognition from the West, by them acknowledging that Feminism is not exclusively European or American.[2]

They also passed a number of other resolutions that focused on social and political equality. It included the retention of "the high spiritual consciousness that has been the fundamental characteristic of the people of Asia throughout the millennia."[2]

Another resolution stated that the lives and teaching of great religious leaders should be taught in schools. Other resolutions favoured free and primary compulsory education; abolition of child marriage; more money to be spent on health schemes; limited temperance schemes; to rescue adult and child from vice; to regulate labour conditions and to ensure equality of status for men and women. The other two favoured national self-determination and world peace.[2]

The conference also ended with the setup for a permanent committee and it was decided that a second conference will be held in either Japan and Java in 1935. The Indian members of the Conference kept meeting annually until 1936 to discuss the desire to have a broader representation and hold the next conference. This execution of the plan kept getting postponed.[2]

However, in 1932, the committee had a collaboration with the Oriental Women's Conference at Tehran with the All India Women's Conference (AIWC) with the hope to have more Asian Women's Conferences. In 1934, the committee grew into a large but short-lived "All Asia Committee" with 50 members from across India. The All Asian Women's Conference received official representation through a permanent delegate to the International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship in Geneva. When this alliance held its 12th congress in Istanbul in 1935, the Asian Committee sent a vocal delegation whose presence did not escape the attending press. However, a second All Asia Women's Conference failed to materialize as many members, including the former host, India got busy with their domestic and international affairs.[6]

See also

References

- Broome 2012, p. .

- Mukherjee 2017.

- Basu & Ray 1990, p. .

- Sandell 2015, p. .

- Nijhawan 2017.

- Frey & Spakowski 2016, p. .

Bibliography

- Basu, Aparna; Ray, Bharati (1990). Women's Struggle: A History of the All India Women's Conference, 1927–1990. Manohar. ISBN 978-81-85425-42-9.

- Broome, Sarah (2012). Stri-Dharma: Voice of the Indian Women's Rights Movement 1928-1936 (Thesis). doi:10.57709/3075581.

- Mukherjee, Sumita (4 May 2017). "The All-Asian Women's Conference 1931: Indian women and their leadership of a pan-Asian feminist organisation". Women's History Review. 26 (3): 363–381. doi:10.1080/09612025.2016.1163924. S2CID 147853155.

- Nijhawan, Shobna (2017). "International Feminism from an Asian Center: The All-Asian Women's Conference (Lahore, 1931) as a Transnational Feminist Moment". Journal of Women's History. 29 (3): 12–36. doi:10.1353/jowh.2017.0031. S2CID 148783279. Project MUSE 669043.

- Sandell, Marie (2015). The Rise of Women's Transnational Activism: Identity and Sisterhood Between the World Wars. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-84885-671-4. OCLC 863174086.

- Frey, Marc; Spakowski, Nicola, eds. (2016). Asianisms: Regionalist Interactions and Asian Integration. NUS Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1nthd7. ISBN 978-9971-69-859-1. JSTOR j.ctv1nthd7. OCLC 1082958633.