Georgia (country)

Georgia (Georgian: საქართველო, romanized: sakartvelo, IPA: [sakʰartʰʷelo] ⓘ) is a country located in Eastern Europe and West Asia. It is part of the Caucasus region, bounded by the Black Sea to the west, Russia to the north and northeast, Turkey to the southwest, Armenia to the south, and by Azerbaijan to the southeast. The country covers an area of 69,700 square kilometres (26,900 sq mi), and has a population of 3.7 million people.[lower-alpha 2][9] Tbilisi is its capital and largest city, home to roughly a third of the Georgian population.

Georgia | |

|---|---|

| Motto: ძალა ერთობაშია Dzala ertobashia "Strength is in Unity" | |

| Anthem: თავისუფლება Tavisupleba "Freedom" | |

.svg.png.webp)  Georgia in dark green; uncontrolled territory in light green | |

| Capital and largest city | Tbilisi 41°43′N 44°47′E |

| Official languages | Georgian |

| Recognised regional languages | Abkhaz[lower-alpha 1] |

| Ethnic groups (2014[a]) |

|

| Religion (2014) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Georgian |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic |

| Salome Zourabichvili | |

| Irakli Garibashvili | |

| Shalva Papuashvili | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Establishment history | |

| 13th c. BC – 580 AD | |

| 786–1008 | |

| 1008 | |

| 1463–1810 | |

| 12 September 1801 | |

| 26 May 1918 | |

| 25 February 1921 | |

• Independence from the Soviet Union • Declared • Finalized | 9 April 1991 26 December 1991 |

| 24 August 1995 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 69,700 km2 (26,900 sq mi) (119th) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 4,012,104[b] (126th) |

• 2014 census | |

• Density | 57.6/km2 (149.2/sq mi) (137th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | very high · 63rd |

| Currency | Georgian lari (₾) (GEL) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (Georgia Time GET) |

| Date format | dd.mm.yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +995 |

| ISO 3166 code | GE |

| Internet TLD | .ge, .გე |

| |

Georgia has been a wine production site since 6,000 BC, being the earliest known location of winemaking in the world.[10][11] During the classical era, several kingdoms emerged in what is now Georgia, such as Colchis and Iberia. In the early 4th century, Georgians officially adopted Christianity, which contributed to the unification of early Georgian states. In the Middle Ages, the unified Kingdom of Georgia reached its Golden Age during the reign of King David IV and Queen Tamar. Thereafter, the kingdom declined and eventually disintegrated under the hegemony of various regional powers, including the Mongols, the Ottoman Empire, and various dynasties of Persia. In 1783, one of the Georgian kingdoms entered into an alliance with the Russian Empire but Russia reneged on its promises and instead proceeded to annex the territory of modern Georgia piece-by-piece against the wish of the local rulers.

After the Russian Revolution in 1917, Georgia emerged as an independent republic under German protection.[12] Following World War I, Georgia was invaded and annexed by the Soviet Union in 1922, becoming one of its constituent republics. In the 1980s, an independence movement grew quickly, leading to Georgia's secession from the Soviet Union in April 1991. For most of the subsequent decade, post-Soviet Georgia suffered from economic crisis, political instability and secessionist wars in Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Following the peaceful Rose Revolution in 2003, Georgia strongly pursued a pro-Western foreign policy; it introduced a series of democratic and economic reforms aimed at integration into the European Union and NATO. The country's Western orientation soon led to worsening relations with Russia, which culminated in the Russo-Georgian War of 2008, and entrenched Russian occupation of a portion of Georgia.

Georgia is a representative democracy governed as a unitary parliamentary republic.[13][14] It is a developing country with a very high Human Development Index. Economic reforms since independence have led to higher levels of economic freedom, as well as reductions in corruption indicators, poverty, and unemployment. It was one of the first countries in the world to legalize cannabis, becoming the only former-socialist state to do so. The country is a member of international organizations, such as the Council of Europe, the OSCE, Eurocontrol, the EBRD, the BSEC, the GUAM, the ADB, the WTO, and the Energy Community.

Etymology

The first mention of the name spelled as Georgia is in Italian on the mappa mundi of Pietro Vesconte dated AD 1320.[15] At the early stage of its appearance in the Latin world, it was not always written in the same transliteration, and the first consonant was being spelt with J as Jorgia.[16] Georgia probably stems from the Persian designation of the Georgians – gurǧān, in the 11th and 12th centuries adapted via Syriac gurz-ān/gurz-iyān and Arabic ĵurĵan/ĵurzan. Lore-based theories were given by the traveller Jacques de Vitry, who explained the name's origin by the popularity of St. George amongst Georgians,[17] while traveller Jean Chardin thought that Georgia came from Greek γεωργός ('tiller of the land'). Alexander Mikaberidze wrote that these century-old explanations for the word Georgia/Georgians are rejected by the scholarly community, who point to the Persian word gurğ/gurğān (گرگ, 'wolf'[18]) as the root of the word.[19] Starting with the Persian word gurğ/gurğān, under this hypothesis, the word was later adopted in numerous other languages, including Slavic and West European languages, as well as, for example, Modern Farsi as گرجستان, /ɡoɾd͡ʒesˈtɒːn/. This term itself might have been established through the ancient Iranian appellation of the near-Caspian region, which was referred to as Gorgan ("land of the wolves").[19][20]

The native name is Sakartvelo (საქართველო; 'land of Kartvelians'), derived from the core central Georgian region of Kartli, recorded from the 9th century, and in extended usage referring to the entire medieval Kingdom of Georgia by the 13th century. The self-designation used by ethnic Georgians is Kartvelebi (ქართველები, i.e. 'Kartvelians'), first attested in the Umm Leisun inscription found in the Old City of Jerusalem.

The medieval Georgian Chronicles present an eponymous ancestor of the Kartvelians, Kartlos, a great-grandson of Japheth. However, scholars agree that the word is derived from the Karts, one of the proto-Georgian tribes that emerged as a dominant group in ancient times.[19] The name Sakartvelo (საქართველო) consists of two parts. Its root, kartvel-i (ქართველ-ი), specifies an inhabitant of the core central-eastern Georgian region of Kartli, or Iberia as it is known in sources of the Eastern Roman Empire.[21] Ancient Greeks (Strabo, Herodotus, Plutarch, Homer, etc.) and Romans (Titus Livius, Tacitus, etc.) referred to early western Georgians as Colchians and eastern Georgians as Iberians (Iberoi, Ἰβηροι in some Greek sources).[22] The Georgian circumfix sa-X-o is a standard geographic construction designating 'the area where X dwell', where X is an ethnonym.[23]

Today, the official name of the country is Georgia, as specified in the English version of the Georgian constitution which reads "Georgia is the name of the state of Georgia."[24] The Georgian language version of the constitution refers to the legal name of country as Georgian: „საქართველო“ Sakartvelo.[25] Before the 1995 constitution came into force, the country's official name was the Republic of Georgia (Georgian: საქართველოს რესპუბლიკა, romanized: Sakartvelos Resp'ublik'a) and it is still sometimes referred to by that name.[26][27]

History

Prehistory

The territory of modern-day Georgia was inhabited by Homo erectus since the Paleolithic Era. The proto-Georgian tribes first appear in written history in the 12th century BC.[28] The earliest evidence of wine to date has been found in Georgia, where 8,000-year old wine jars were uncovered.[29][30] Archaeological finds and references in ancient sources also reveal elements of early political and state formations characterized by advanced metallurgy and goldsmith techniques that date back to the 7th century BC and beyond.[28] In fact, early metallurgy started in Georgia during the 6th millennium BC, associated with the Shulaveri-Shomu culture.[31]

Antiquity

Archaeological evidence indicates that Georgia has been the site of wine production since at least 6,000 BC, which over time played a role in forming Georgia's culture and national identity.[32][33] The classical period saw the rise of a number of early Georgian states, the principal of which were Colchis in the west and Iberia in the east. In Greek mythology, Colchis was the location of the Golden Fleece sought by Jason and the Argonauts in Apollonius Rhodius' epic tale Argonautica. The incorporation of the Golden Fleece into the myth may have derived from the local practice of using fleeces to sift gold dust from rivers.[34] In the 4th century BC, a kingdom of Iberia – an early example of advanced state organization under one king and an aristocratic hierarchy – was established.[35]

After the Roman Republic completed its brief conquest of what is now Georgia in 66 BC, the area became a primary objective of what would eventually turn out to be over 700 years of protracted Irano-Roman geo-political rivalry and warfare.[36][37] From the first centuries AD, the cult of Mithras, pagan beliefs, and Zoroastrianism were commonly practised in Georgia.[38] In 337 AD King Mirian III declared Christianity as the state religion, giving a great stimulus to the development of literature, arts, and ultimately playing a key role in the formation of the unified Georgian nation,[39][40] The acceptance led to the slow but sure decline of Zoroastrianism,[41] which until the 5th century AD, appeared to have become something like a second established religion in Iberia (eastern Georgia), and was widely practised there.[42]

Middle Ages up to early modern period

Located on the crossroads of protracted Roman–Persian wars, 54 BC – 628 AD (681 years), the early Georgian kingdoms disintegrated into various feudal regions by the early Middle Ages. This made it easy for the remaining Georgian realms to fall victim to the early Muslim conquests in 645, the 7th century.

Rise of Bagratid Iberia

The extinction of the Iberian royal dynasties, such as Guaramids and the Chosroids,[43] and also the Abbasid preoccupation with their own civil wars and conflict with the Byzantine Empire, led to the Bagrationi family's growth in prominence. The head of the Bagrationi dynasty Ashot I of Iberia (r. 813–826), who had migrated to the former southwestern territories of Iberia, came to rule over Tao-Klarjeti and restored the Principate of Iberia in 813. The sons and grandsons of Ashot I established three separate branches, frequently struggling with each other and with neighbouring rulers. The Kartli line prevailed; in 888 Adarnase IV of Iberia (r. 888–923) restored the indigenous royal authority dormant since 580. Despite the revitalization of the Iberian monarchy, remaining Georgian lands were divided among rival authorities, with Tbilisi remaining in Arab hands.

Kingdom of Abkhazia

An Arab incursion into western Georgia led by Marwan II, was repelled by Leon I (r. 720–740) jointly with his Lazic and Iberian allies in 736. Leon I then married Mirian's daughter, and a successor, Leon II exploited this dynastic union to acquire Lazica in the 770s.[44] The successful defence against the Arabs, and new territorial gains, gave the Abkhazian princes enough power to claim more autonomy from the Byzantine Empire. Towards 778, Leon II (r. 780–828) won his full independence with the help of the Khazars and was crowned as the king of Abkhazia. After obtaining independence for the state, the matter of church independence became the main problem. In the early 9th century the Abkhazian Church broke away from Constantinople and recognized the authority of the Catholicate of Mtskheta; the Georgian language replaced Greek as the language of literacy and culture.[45][46] The most prosperous period of the Abkhazian kingdom was between 850 and 950. A bitter civil war and feudal revolts which began under Demetrius III (r. 967–975) led the kingdom into complete anarchy under the unfortunate king Theodosius III the Blind (r. 975–978). A period of unrest ensued, which ended as Abkhazia and eastern Georgian states were unified under a single Georgian monarchy, ruled by King Bagrat III of Georgia (r. 975–1014), due largely to the diplomacy and conquests of his energetic foster-father David III of Tao (r. 966–1001).

United Georgian monarchy

The stage of feudalism's development and struggle against common invaders as much as common belief of various Georgian states had an enormous importance for spiritual and political unification of Georgia feudal monarchy under the Bagrationi dynasty in the 11th century.

The Kingdom of Georgia reached its zenith in the 12th to early 13th centuries. This period during the reigns of David IV (r. 1089–1125) and his great-granddaughter Tamar (r. 1184–1213) has been widely termed as Georgia's Golden Age or the Georgian Renaissance.[47] This early Georgian renaissance, which preceded its Western European analogue, was characterized by impressive military victories, territorial expansion, and a cultural renaissance in architecture, literature, philosophy and the sciences.[48] The Golden age of Georgia left a legacy of great cathedrals, romantic poetry and literature, and the epic poem The Knight in the Panther's Skin, the latter which is considered a national epic.[49][50]

David suppressed dissent of feudal lords and centralized the power in his hands to effectively deal with foreign threats. In 1121, he decisively defeated much larger Turkish armies during the Battle of Didgori and liberated Tbilisi.[51]

.jpg.webp)

The 29-year reign of Tamar, the first female ruler of Georgia, is considered the most successful in Georgian history.[53] Tamar was given the title "king of kings" (mepe mepeta).[52] She succeeded in neutralizing opposition and embarked on an energetic foreign policy aided by the downfall of the rival powers of the Seljuks and Byzantium. Supported by a powerful military élite, Tamar was able to build on the successes of her predecessors to consolidate an empire which dominated the Caucasus, and extended over large parts of present-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, and eastern Turkey as well as parts of northern Iran,[54] until its collapse under the Mongol attacks within two decades after Tamar's death in 1213.[55]

The revival of the Kingdom of Georgia was set back after Tbilisi was captured and destroyed by the Khwarezmian leader Jalal ad-Din in 1226.[56] The Mongols were expelled by George V of Georgia (r. 1299–1302), son of Demetrius II of Georgia (r. 1270–1289), who was named "Brilliant" for his role in restoring the country's previous strength and Christian culture. George V was the last great king of the unified Georgian state. After his death, local rulers fought for their independence from central Georgian rule, until the total disintegration of the Kingdom in the 15th century. Georgia was further weakened by several disastrous invasions by Tamerlane. Invasions continued, giving the kingdom no time for restoration, with both Black and White sheep Turkomans constantly raiding its southern provinces.

Tripartite division

.jpg.webp)

The Kingdom of Georgia collapsed into anarchy by 1466 and fragmented into three independent kingdoms and five semi-independent principalities. Neighboring large empires subsequently exploited the internal division of the weakened country, and beginning in the 16th century up to the late 18th century, Safavid Iran (and successive Iranian Afsharid and Qajar dynasties) and Ottoman Turkey subjugated the eastern and western regions of Georgia, respectively.[57]

The rulers of regions that remained partly autonomous organized rebellions on various occasions. However, subsequent Iranian and Ottoman invasions further weakened local kingdoms and regions. As a result of incessant Ottoman–Persian Wars and deportations, the population of Georgia dwindled to 784,700 inhabitants at the end of the 18th century.[58] Eastern Georgia (Safavid Georgia), composed of the regions of Kartli and Kakheti, had been under Iranian suzerainty since 1555 following the Peace of Amasya signed with neighbouring rivalling Ottoman Turkey. With the death of Nader Shah in 1747, both kingdoms broke free of Iranian control and were reunified through a personal union under the energetic king Heraclius II in 1762. Heraclius, who had risen to prominence through the Iranian ranks, was awarded the crown of Kakheti by Nader himself in 1744 for his loyal service to him.[59] Heraclius nevertheless stabilized Eastern Georgia to a degree in the ensuing period and was able to guarantee its autonomy throughout the Iranian Zand period.[60]

In 1783, Russia and the eastern Georgian Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti signed the Treaty of Georgievsk, by which Georgia abjured any dependence on Persia or another power, and made the kingdom a protectorate of Russia, which guaranteed Georgia's territorial integrity and the continuation of its reigning Bagrationi dynasty in return for prerogatives in the conduct of Georgian foreign affairs.[61]

However, despite this commitment to defend Georgia, Russia rendered no assistance when the Iranians invaded in 1795, capturing and sacking Tbilisi while massacring its inhabitants, as the new heir to the throne sought to reassert Iranian hegemony over Georgia.[62] Despite a punitive campaign subsequently launched against Qajar Iran in 1796, this period culminated in the 1801 Russian violation of the Treaty of Georgievsk and annexation of eastern Georgia, followed by the abolition of the royal Bagrationi dynasty, as well as the autocephaly of the Georgian Orthodox Church. Pyotr Bagration, one of the descendants of the abolished house of Bagrationi, would later join the Russian army and rise to be a prominent general in the Napoleonic wars.[63]

Within the Russian Empire

On 22 December 1800, Tsar Paul I of Russia, at the alleged request of the Georgian King George XII, signed the proclamation on the incorporation of Georgia (Kartli-Kakheti) within the Russian Empire, which was finalized by a decree on 8 January 1801,[64][65] and confirmed by Tsar Alexander I on 12 September 1801.[66][67] The Bagrationi royal family was deported from the kingdom. The Georgian envoy in Saint Petersburg reacted with a note of protest that was presented to the Russian vice-chancellor Prince Kurakin.[68]

In May 1801, under the oversight of General Carl Heinrich von Knorring, Imperial Russia transferred power in eastern Georgia to the government headed by General Ivan Petrovich Lazarev.[69] The Georgian nobility did not accept the decree until 12 April 1802, when Knorring assembled the nobility at the Sioni Cathedral and forced them to take an oath on the Imperial Crown of Russia. Those who disagreed were temporarily arrested.[70]

In the summer of 1805, Russian troops on the Askerani River near Zagam defeated the Iranian army during the 1804–13 Russo-Persian War and saved Tbilisi from reconquest now that it was officially part of the Imperial territories. Russian suzerainty over eastern Georgia was officially finalized with Iran in 1813 following the Treaty of Gulistan.[71] Following the annexation of eastern Georgia, the western Georgian kingdom of Imereti was annexed by Tsar Alexander I. The last Imeretian king and the last Georgian Bagrationi ruler, Solomon II, died in exile in 1815, after attempts to rally people against Russia and to enlist foreign support against the latter, had been in vain.[72]

From 1803 to 1878, as a result of numerous Russian wars now against Ottoman Turkey, several of Georgia's previously lost territories – such as Adjara – were recovered, and also incorporated into the empire. The principality of Guria was abolished and incorporated into the Empire in 1829, while Svaneti was gradually annexed in 1858. Mingrelia, although a Russian protectorate since 1803, was not absorbed until 1867.[73]

Russian rule offered the Georgians security from external threats, but it was also often heavy-handed and insensitive. By the late 19th century, discontent with the Russian authorities grew into a national revival movement led by Ilia Chavchavadze. This period also brought social and economic change to Georgia, with new social classes emerging: the emancipation of the serfs freed many peasants but did little to alleviate their poverty; the growth of capitalism created an urban working class in Georgia. Both peasants and workers found expression for their discontent through revolts and strikes, culminating in the Revolution of 1905. Their cause was championed by the socialist Mensheviks, who became the dominant political force in Georgia in the final years of Russian rule.

Declaration of independence

After the Russian Revolution of 1917, the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic was established with Nikolay Chkheidze acting as its president. The federation consisted of three nations: Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan.[12] As the Ottomans advanced into the Caucasian territories of the crumbling Russian Empire, Georgia declared independence on 26 May 1918.[74] The Menshevik Social Democratic Party of Georgia won the parliamentary election and its leader, Noe Zhordania, became prime minister. Despite the Soviet takeover, Zhordania was recognized as the legitimate head of the Georgian Government by France, UK, Belgium, and Poland through the 1930s.[75]

The 1918 Georgian–Armenian War, which erupted over parts of disputed provinces between Armenia and Georgia populated mostly by Armenians, ended because of British intervention. In 1918–1919, Georgian general Giorgi Mazniashvili led an attack against the White Army led by Moiseev and Denikin in order to claim the Black Sea coastline from Tuapse to Sochi and Adler for the independent Georgia.[76] In 1920 Soviet Russia recognized Georgia's independence with the Treaty of Moscow. But the recognition proved to be of little value, as the Red Army invaded Georgia in 1921 and formally annexed it into the Soviet Union in 1922.[74]

Soviet Socialist Republic

In February 1921, during the Russian Civil War, the Red Army advanced into Georgia and brought the local Bolsheviks to power. The Georgian army was defeated and the Social Democratic government fled the country. On 25 February 1921, the Red Army entered Tbilisi and established a government of workers' and peasants' soviets with Filipp Makharadze as acting head of state. Georgia was incorporated into the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic, alongside Armenia and Azerbaijan, in 1921 which in 1922 would become a founding member of the Soviet Union. Soviet rule was firmly established only after the insurrection was swiftly defeated.[77] Georgia would remain an unindustrialized periphery of the USSR until the first five-year plan when it became a major centre for textile goods. Later, in 1936, the TSFSR was dissolved and Georgia emerged as a union republic: the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Joseph Stalin, an ethnic Georgian born Iosif Vissarionovich Jugashvili (იოსებ ბესარიონის ძე ჯუღაშვილი) in Gori, was prominent among the Bolsheviks.[78] Stalin was to rise to the highest position, leading the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death on 5 March 1953.

In June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union on an immediate course towards Caucasian oil fields and munitions factories. They never reached Georgia, however, and almost 700,000 Georgians fought in the Red Army to repel the invaders and advance towards Berlin. Of them, an estimated 350,000 were killed.[79]

After Stalin's death, Nikita Khrushchev became the leader of the Soviet Union and implemented a policy of de-Stalinization. This was nowhere else more publicly and violently opposed than in Georgia, where in 1956 riots broke out upon the release of Khrushchev's public denunciation of Stalin, which had to be dispersed by military force.

Throughout the remainder of the Soviet period, Georgia's economy continued to grow and experience significant improvement, though it increasingly exhibited blatant corruption and alienation of the government from the people. With the beginning of perestroika in 1986, the Georgian Soviet leadership proved so incapable of handling the changes that most Georgians, including rank and file communists, concluded that the only way forward was a break from the existing Soviet system.

After restoration of independence

On 9 April 1991, shortly before the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Supreme Council of Georgia declared independence after a referendum held on 31 March.[80] Georgia was the first non-Baltic republic of the Soviet Union to officially declare independence.[81] In August 1991, Romania became the first country to recognize Georgia.[82]

On 26 May, Zviad Gamsakhurdia was elected as the first President of independent Georgia. Gamsakhurdia stoked Georgian nationalism and vowed to assert Tbilisi's authority over regions such as Abkhazia and South Ossetia that had been classified as autonomous within the Georgian SSR.[83]

He was soon deposed in a bloody coup d'état, from 22 December 1991 to 6 January 1992. The coup was instigated by part of the National Guards and a paramilitary organization called "Mkhedrioni" ("horsemen"). The country then became embroiled in a bitter civil war, which lasted until 1994. Simmering disputes within two regions of Georgia; Abkhazia and South Ossetia, between local separatists and the majority Georgian populations, erupted into widespread inter-ethnic violence and wars.[83] Supported by Russia, Abkhazia and South Ossetia achieved de facto independence from Georgia, with Georgia retaining control only in small areas of the disputed territories.[83] Eduard Shevardnadze (Soviet Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1985 to 1991) returned to Georgia in 1992 and was elected as head of state in that year's elections, and as president in 1995.[84]

During the War in Abkhazia (1992–1993), roughly 230,000 to 250,000 Georgians[85] were expelled from Abkhazia by Abkhaz separatists and North Caucasian volunteers (including Chechens). Around 23,000 Georgians fled South Ossetia as well.[86]

.jpg.webp)

In 2003, Shevardnadze (who won re-election in 2000) was deposed by the Rose Revolution, after Georgian opposition and international monitors asserted that 2 November parliamentary elections were marred by fraud.[87] The revolution was led by Mikheil Saakashvili, Zurab Zhvania and Nino Burjanadze, former members and leaders of Shevardnadze's ruling party. Mikheil Saakashvili was elected as President of Georgia in 2004.[88]

Following the Rose Revolution, a series of reforms were launched to strengthen the country's military and economic capabilities, as well as to reorient its foreign policy westwards. The new government's efforts to reassert Georgian authority in the southwestern autonomous republic of Adjara led to a major crisis in 2004.[89]

The country's newly pro-Western stance, along with accusations of Georgian involvement in the Second Chechen War,[90] resulted in a severe deterioration of relations with Russia, fuelled also by Russia's open assistance and support to the two secessionist areas. Despite these increasingly difficult relations, in May 2005 Georgia and Russia reached a bilateral agreement[91] by which Russian military bases (dating back to the Soviet era) in Batumi and Akhalkalaki were withdrawn. Russia withdrew all personnel and equipment from these sites by December 2007[92] while failing to withdraw from the Gudauta base in Abkhazia, which it was required to vacate after the adoption of the Adapted Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty during the 1999 Istanbul summit.[93]

Russo-Georgian War and since

There was a Russo-Georgian diplomatic crisis in April 2008.[94][95] A bomb explosion on 1 August 2008 targeted a car transporting Georgian peacekeepers. South Ossetians were responsible for instigating this incident, which marked the opening of hostilities and injured five Georgian servicemen, then several South Ossetian militiamen were killed by snipers.[96][97] South Ossetian separatists began shelling Georgian villages on 1 August. These artillery bombardments caused Georgian servicemen to return fire periodically.[94][97][98][99][100]

On 7 August 2008, the Georgian president Mikheil Saakashvili announced a unilateral ceasefire and called for peace talks.[101] More attacks on Georgian villages (located in the South Ossetian conflict zone) were soon matched with gunfire from Georgian troops, who then proceeded to move in the direction of the capital of the self-proclaimed Republic of South Ossetia (Tskhinvali) on the night of 8 August, reaching its centre in the morning of 8 August.[102][103][104] According to Russian military expert Pavel Felgenhauer, the Ossetian provocation was aimed at triggering Georgian retaliation, which was needed as a pretext for a Russian military invasion.[105] According to Georgian intelligence and several Russian media reports, parts of the regular (non-peacekeeping) Russian Army had already moved to South Ossetian territory through the Roki Tunnel before the Georgian military action.[106][107]

Russia accused Georgia of "aggression against South Ossetia" and began a big land, air and sea invasion of Georgia under the pretext of a "peace enforcement" operation on 8 August 2008.[108][99] Abkhaz forces opened a second front on 9 August with the Battle of the Kodori Valley, an attack on the Kodori Gorge, held by Georgia.[109] Tskhinvali was seized by the Russian military by 10 August.[110] Russian forces occupied Georgian cities beyond the disputed territories.[111]

During the conflict, there was a campaign of ethnic cleansing against Georgians in South Ossetia, including destruction of Georgian settlements after the war had ended.[112][113] The war displaced 192,000 people and while many were able to return to their homes after the war, a year later around 30,000 ethnic Georgians remained displaced.[114][115] In an interview published in Kommersant, South Ossetian leader Eduard Kokoity said he would not allow Georgians to return.[116][117]

The President of France, Nicolas Sarkozy, negotiated a ceasefire agreement on 12 August 2008.[118] Russia recognized Abkhazia and South Ossetia as separate republics on 26 August.[119] The Georgian government severed diplomatic relations with Russia.[120] Russian forces left the buffer areas bordering Abkhazia and South Ossetia on 8 October and the European Union Monitoring Mission in Georgia was dispatched to the buffer areas.[121][122] Since the war, Georgia has maintained that Abkhazia and South Ossetia are occupied Georgian territories.[123][124] Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Georgia has topped the list of countries which Russian exiles departed to after the war began; Russians are allowed to stay in Georgia for at least one year without a visa, though many Georgians view the presence of more Russian citizens in Georgia as a security risk.[125]

Government and politics

.jpg.webp) |  |

| Salome Zourabichvili President |

Irakli Garibashvili Prime Minister |

Georgia is a representative democratic parliamentary republic, with the President as the largely ceremonial[126] head of state, and Prime Minister as the head of government. The executive branch of power is made up of the Cabinet of Georgia. The Cabinet is composed of ministers, headed by the Prime Minister, and appointed by the Parliament. Salome Zurabishvili is the current President of Georgia after winning 59.52% of the vote in the 2018 Georgian presidential election. Since February 2021, Irakli Gharibashvili has been the prime minister of Georgia.

Legislative authority is vested in the Parliament of Georgia. It is unicameral and has 150 members, known as deputies, of whom 30 are elected by plurality to represent single-member districts, and 120 are chosen to represent parties by proportional representation. Members of parliament are elected for four-year terms. On 26 May 2012, Saakashvili inaugurated a new Parliament building in the western city of Kutaisi, in an effort to decentralize power and shift some political control closer to Abkhazia.[127] Saakashvili's rivals, who came to power later in 2012, never truly accepted the move to Kutaisi and six years later Parliament returned to its old location in Tbilisi after adapting the constitutional clause.[128]

Different opinions exist regarding the degree of political freedom in Georgia. Saakashvili believed in 2008 that the country is "on the road to becoming a European democracy."[129] In their 2022 report Freedom House lists Georgia as a partly free country, recognizing a trajectory of democratic improvement surrounding the 2012–13 transfer of power, yet observing a gradual backslide in later years.[130] In their Democracy Index 2021 report the Economist Intelligence Unit classifies Georgia as a hybrid regime which is above the threshold for an authoritarian regime but below the threshold needed to be classified as a flawed democracy.[131]

Recent political developments

In preparation for the 2012 parliamentary elections, Georgia implemented constitutional reforms to switch to a parliamentary democracy, moving executive powers from the President to the Prime Minister.[133] The transition was set to start with the October 2012 parliamentary elections and to be completed with the 2013 presidential elections.

Against the expectations of the then ruling United National Movement (UNM) of president Mikheil Saakashvili, the 6-party opposition coalition around newly founded Georgian Dream won the parliamentary elections in October 2012, bringing an end to nine years of UNM rule and marking the first peaceful electoral transfer of power in Georgia. President Saakashvili acknowledged the defeat of his party on the following day.[134] Georgian Dream was founded, led and financed by tycoon Bidzina Ivanishvili, the country's richest man who was subsequently elected by parliament as new Prime Minister.[135] Due to the incomplete transition to parliamentary democracy, a year of uneasy cohabitation between rivals Ivanishvili and Saakashvili followed until the October 2013 presidential elections.[136][137]

In October 2013, Giorgi Margvelashvili, a candidate of the Georgian Dream party, won the presidential election. Margvelashvili succeeded president Mikheil Saakashvili, who had served the maximum of two terms since coming to power after the bloodless 2003 "Rose Revolution".[138] However, the new constitution made the role of president largely ceremonial. With the completed transfer of power, Prime Minister Ivanishvili stepped aside and named one of his close business associates as next Prime Minister.[139] Ivanishvili has since been called the informal leader of Georgia, arranging political reappointments from behind the scenes.[140]

In October 2016, the ruling party Georgian Dream won the parliamentary elections with 48.61 percent of the vote while the opposition United National Movement (UNM) gained 27.04 percent of the vote.[141] Most of Georgian Dream's coalition parties had left the coalition and landed outside of parliament. As result of the mixed proportional-majoritarian system, with a threshold of 5% for the proportional vote and redefined majoritarian districts, only four parties entered parliament, with the Georgian Dream party gaining a constitutional majority of 77% (+36 seats). This electoral imbalance became a key issue of political and civil society strife in the following years.[142][143][144] After international mediation to overcome the deep political crisis in the runup to the 2020 parliamentary elections an amended electoral system was adopted, specifically for the 2020 elections.[145]

Meanwhile, Salome Zurabishvili won the 2018 presidential election in two rounds, becoming the first woman in Georgia to hold the office in full capacity after Parliament Speaker Nino Burjanadze held the office as female interim President twice, in 2003 and 2007. Zurabishvili was backed by the ruling Georgian Dream party. It was the last direct election of a Georgian president, as additional constitutional reforms removed the popular vote.[146]

On 31 October 2020, the ruling Georgian Dream again led by Bidzina Ivanishvili secured over 48% of votes in the parliamentary election under a different electoral system. 120 parliamentary seats were elected through proportional vote while 30 seats were elected through single mandate majoritarian constituencies. The threshold for the proportional vote was lowered to 1%, which resulted in 9 parties being represented in parliament. As the largest faction, having secured 90 out of 150 seats, Georgian Dream formed the country's next government and continued to govern alone. The opposition made accusations of fraud, which the Georgian Dream denied. Thousands of people gathered outside the Central Election Commission to demand a new vote.[147] This led to a new political crisis that was (temporarily) resolved with an EU brokered agreement,[148] from which the Georgian Dream later withdrew.[149]

In February 2021, Irakli Garibashvili became Prime Minister of Georgia, following the resignation of Prime Minister Giorgi Gakharia.[150] Garibashvili, who had an earlier term as prime minister in 2013–15, is known as a political hardliner.[151]

On 1 October 2021, former President Mikheil Saakashvili was arrested on his return from exile. Saakashvili led the country from 2004 to 2013 but was later convicted in absentia on corruption charges and abuse of power, which he denied.[152]

Foreign relations

Georgia maintains good relations with its direct neighbours Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey, and is a member of the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the World Trade Organization, the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the Community of Democratic Choice, the GUAM Organization for Democracy and Economic Development, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development[153] and the Asian Development Bank.[154] Georgia also maintains political, economic, and military relations with France,[155] Germany,[156] Israel,[157] Japan,[158] South Korea,[159] Sri Lanka,[160] Turkey,[161] Ukraine,[162] the United States,[163] and many other countries.[164]

The explicit western orientation of Georgia, deepening political ties with the US and European Union, notably through its EU and NATO membership aspirations, the US Train and Equip military assistance programme, and the construction of the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline, increasingly strained Tbilisi's relations with Moscow in the early 2000s. Georgia's decision to boost its presence in the coalition forces in Iraq was an important initiative.[165] The European Union has identified Georgia as a prospective member,[166] and Georgia has sought membership.[167]

Georgia is currently working to become a full member of NATO. In August 2004, the Individual Partnership Action Plan of Georgia was submitted officially to NATO. On 29 October 2004, the North Atlantic Council of NATO approved the Individual Partnership Action Plan (IPAP) of Georgia, and Georgia moved on to the second stage of Euro-Atlantic Integration. In 2005, the agreement on the appointment of Partnership for Peace (PfP) liaison officer between Georgia and NATO came into force, whereby a liaison officer for the South Caucasus was assigned to Georgia. On 2 March 2005, the agreement was signed on the provision of the host nation support to and transit of NATO forces and NATO personnel. On 6–9 March 2006, the IPAP implementation interim assessment team arrived in Tbilisi. On 13 April 2006, the discussion of the assessment report on implementation of the Individual Partnership Action Plan was held at NATO Headquarters, within 26+1 format.[168] The majority of Georgians and politicians in Georgia support the push for NATO membership.[169]

.jpg.webp)

In 2011, the North Atlantic Council designated Georgia as an "aspirant country".[170] Since 2014, Georgia–NATO relations are guided by the Substantial NATO–Georgia Package (SNGP), which includes the NATO–Georgia Joint Training and Evaluation Centre and facilitation of multi-national and regional military drills.[171]

In September 2019, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that "NATO approaching our borders is a threat to Russia."[172] He was quoted as saying that if NATO accepts Georgian membership with the article on collective defence covering only Tbilisi-administered territory (i.e., excluding the Georgian territories Abkhazia and South Ossetia, both of which are currently Russian-supported unrecognized breakaway republics), "we will not start a war, but such conduct will undermine our relations with NATO and with countries who are eager to enter the alliance."[173]

George W. Bush became the first sitting US president to visit the country.[174] The street leading to Tbilisi International Airport has since been dubbed George W. Bush Avenue.[175] On 2 October 2006, Georgia and the European Union signed a joint statement on the agreed text of the Georgia–European Union Action Plan within the European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP). The Action Plan was formally approved at the EU–Georgia Cooperation Council session on 14 November 2006, in Brussels.[176] In June 2014, the EU and Georgia signed an Association Agreement, which entered into force on 1 July 2016.[177] On 13 December 2016, EU and Georgia reached the agreement on visa liberalization for Georgian citizens.[178] On 27 February 2017, the Council adopted a regulation on visa liberalization for Georgians travelling to the EU for a period of stay of 90 days in any 180-day period.[179]

Georgia applied for EU membership on 3 March 2022, soon after the beginning of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[180]

Military

Georgia's military is organized into land and air forces. They are collectively known as the Georgian Defense Forces (GDF). The mission and functions of the GDF are based on the Constitution of Georgia, Georgia's Law on Defense and National Military Strategy, and international agreements to which Georgia is signatory. The military budget of Georgia for 2021 is 900₾ ($280) million. The biggest part, 72% of the military budget is allocated for maintaining defence forces readiness and potency development.[181] After its independence from the Soviet Union, Georgia began to develop its own military industry. The first exhibition of products made by STC Delta was in 1999.[182] STC Delta now produces a variety of military equipment, including armoured vehicles, artillery systems, aviation systems, personal protection equipment, and small arms.[183]

During later periods of the Iraq War Georgia had up to 2,000 soldiers serving in the Multi-National Force.[184] Georgia also participated in the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force in Afghanistan; with 1,560 troops in 2013, it was at that time the largest contributor among non-NATO countries[185] and in per capita terms.[186][187] Over 11,000 Georgian soldiers have been rotated through Afghanistan.[188] As of 2015, 31 Georgian servicemen have died in Afghanistan,[189] most during the Helmand campaign. In addition, 435 were wounded, including 35 amputees.[190][191]

Law enforcement

In Georgia, law enforcement is conducted and provided for by the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia. In recent years, the Patrol Police Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia has undergone a radical transformation, with the police having now absorbed a great many duties previously performed by dedicated independent government agencies. New duties performed by the police include border security and customs functions and contracted security provision; the latter function is performed by the dedicated 'security police'.

In 2005, President Mikheil Saakashvili fired the entire traffic police force (numbering around 30,000 police officers) of the Georgian National Police due to corruption.[192][193] A new force was then subsequently built around new recruits.[192] The US State Department's Bureau of International Narcotics and Law-Enforcement Affairs has provided assistance to the training efforts and continues to act in an advisory capacity.[194]

The new Patruli force was first introduced in the summer of 2005 to replace the traffic police, a force which was accused of widespread corruption.[195] The police introduced a 0-2-2 (currently, 1-1-2) emergency dispatch service in 2004.[196]

Corruption

Prior to the Rose Revolution, Georgia was among the most corrupt countries in the world.[197] However, following the reforms brought by the peaceful revolution, corruption in the country abated dramatically. In 2010, Transparency International (TI) named Georgia "the best corruption-buster in the world."[198] In 2012, the World Bank called Georgia a "unique success" of the world in fighting corruption, noting "Georgia's experience shows that the vicious cycle of endemic corruption can be broken and, with appropriate and decisive reforms, can be turned into a virtuous cycle."[199]

Although Georgia has been very successful in reducing blatant forms of corruption, other more subtle corrupt practices have been noted. For example, in its 2017 report, Council of Europe observed that while most day-to-day corruption has been eliminated, there are some indications of a "clientelistic system" whereby the country's leadership may allocate resources in ways that generate the loyalty and support it needs to stay in power.[200] Since 2012 stagnation in corruption fighting efforts can be observed, according to Transparency International.[201] Since 2016 the Transparency International Corruption Perception Index hovers around 56 out of 100 points. In comparison, that places Georgia in the top 50 out of 180 countries, among Central European and Mediterranean EU member states.[202]

Human rights

Human rights in Georgia are guaranteed by the country's constitution. There is an independent human rights public defender elected by the Parliament of Georgia to ensure such rights are enforced.[203] Georgia has ratified the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities in 2005. NGO "Tolerance", in its alternative report about its implementation, speaks of a rapid decrease in the number of Azerbaijani schools and cases of appointing headmasters to Azerbaijani schools who do not speak the Azerbaijani language.[204]

The government came under criticism for its alleged use of excessive force on 26 May 2011 when it dispersed protesters led by Nino Burjanadze, among others, with tear gas and rubber bullets after they refused to clear Rustaveli Avenue for an independence day parade despite the expiration of their demonstration permit and despite being offered to choose an alternative venue.[205][206][207][208] While human rights activists maintained that the protests were peaceful, the government pointed out that many protesters were masked and armed with heavy sticks and molotov cocktails.[209] Georgian opposition leader Nino Burjanadze said the accusations of planning a coup were baseless, and that the protesters' actions were legitimate.[208][210]

Since independence, Georgia maintained harsh policies against drugs, handing out lengthy sentences even for marijuana use. This came under criticism from human rights activists[211] and led to protests.[212] In response to lawsuits from civil society organizations, in 2018 the Constitutional Court of Georgia ruled that "consumption of marijuana is an action protected by the right to free personality"[213] and that "[Marijuana] can only harm the user's health, making that user him/herself responsible for the outcome. The responsibility for such actions does not cause dangerous consequences for the public."[214] With this ruling, Georgia became one of the first countries in the world to legalize cannabis, although using the drug in the presence of children is still illegal and punishable by fines or imprisonment.[215]

Administrative divisions

Georgia is administratively divided into 9 regions, 1 capital region, and 2 autonomous republics. These in turn are subdivided into 67 districts and 5 self-governing cities.[216]

Georgia contains two official autonomous regions, of which one has declared independence. Officially autonomous within Georgia,[217] the de facto independent region of Abkhazia declared independence in 1999.[218] In addition, another territory not officially autonomous has also declared independence. South Ossetia is officially known by Georgia as the Tskinvali region, as it views "South Ossetia" as implying political bonds with Russian North Ossetia.[219] It was called South Ossetian Autonomous Oblast when Georgia was part of Soviet Union. Its autonomous status was revoked in 1990. De facto separate since Georgian independence, offers were made to give South Ossetia autonomy again, but in 2006 an unrecognized referendum in the area resulted in a vote for independence.[219]

In both Abkhazia and South Ossetia large numbers of people had been given Russian passports, some through a process of forced passportization by Russian authorities.[220] This was used as a justification for Russian invasion of Georgia during the 2008 South Ossetia war after which Russia recognized the region's independence.[221] Georgia considers the regions as occupied by Russia.[123][222] The two self-declared republics gained limited international recognition after the 2008 Russo-Georgian War. Most countries consider the regions to be Georgian territory under Russian occupation.[223]

| Region | Centre | Area (km2) | Population[5] | Density |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abkhazia | Sukhumi | 8,660 | 242,862est | 28.04 |

| Adjara | Batumi | 2,880 | 333,953 | 115.95 |

| Guria | Ozurgeti | 2,033 | 113,350 | 55.75 |

| Imereti | Kutaisi | 6,475 | 533,906 | 82.45 |

| Kakheti | Telavi | 11,311 | 318,583 | 28.16 |

| Kvemo Kartli | Rustavi | 6,072 | 423,986 | 69.82 |

| Mtskheta-Mtianeti | Mtskheta | 6,786 | 94,573 | 13.93 |

| Racha-Lechkhumi and Kvemo Svaneti | Ambrolauri | 4,990 | 32,089 | 6.43 |

| Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti | Zugdidi | 7,440 | 330,761 | 44.45 |

| Samtskhe-Javakheti | Akhaltsikhe | 6,413 | 160,504 | 25.02 |

| Shida Kartli | Gori | 5,729 | 300,382est | 52.43 |

| Tbilisi | Tbilisi | 720 | 1,108,717 | 1,539.88 |

Geography

Georgia is a mountainous country situated almost entirely in the South Caucasus, while some slivers of the country are situated north of the Caucasus Watershed in the North Caucasus.[224][225] The country lies between latitudes 41° and 44° N, and longitudes 40° and 47° E, with an area of 67,900 km2 (26,216 sq mi). The Likhi Range divides the country into eastern and western halves.[226] Historically, the western portion of Georgia was known as Colchis while the eastern plateau was called Iberia.[227]

The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range forms the northern border of Georgia.[226] The main roads through the mountain range into Russian territory lead through the Roki Tunnel between Shida Kartli and North Ossetia and the Darial Gorge (in the Georgian region of Khevi). The southern portion of the country is bounded by the Lesser Caucasus Mountains.[226] The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range is much higher in elevation than the Lesser Caucasus Mountains, with the highest peaks rising more than 5,000 metres (16,404 ft) above sea level.

The highest mountain in Georgia is Mount Shkhara at 5,203 metres (17,070 ft), and the second highest is Mount Janga at 5,059 m (16,598 ft) above sea level. Other prominent peaks include Mount Kazbek at 5,047 m (16,558 ft), Shota Rustaveli Peak 4,960 m (16,273 ft), Tetnuldi 4,858 m (15,938 ft), Ushba 4,700 m (15,420 ft), and Ailama 4,547 m (14,918 ft).[226] Out of the abovementioned peaks, only Kazbek is of volcanic origin. The region between Kazbek and Shkhara (a distance of about 200 km (124 mi) along the Main Caucasus Range) is dominated by numerous glaciers.[227]

.jpg.webp)

The term Lesser Caucasus Mountains is often used to describe the mountainous (highland) areas of southern Georgia that are connected to the Greater Caucasus Mountain Range by the Likhi Range.[226] The area can be split into two separate sub-regions; the Lesser Caucasus Mountains, which run parallel to the Greater Caucasus Range, and the Southern Georgia Volcanic Highland. The overall region can be characterized as being made up of various, interconnected mountain ranges (largely of volcanic origin) and plateaus that do not exceed 3,400 metres (11,155 ft) in elevation. Prominent features of the area include the Javakheti Volcanic Plateau, lakes, including Tabatskuri and Paravani, as well as mineral water and hot springs. Two major rivers in Georgia are the Rioni and the Mtkvari.[227]

Topography

The landscape within the nation's boundaries is quite varied. Western Georgia's landscape ranges from low-land marsh-forests, swamps, and temperate rainforests to eternal snows and glaciers, while the eastern part of the country even contains a small segment of semi-arid plains.[227]

Much of the natural habitat in the low-lying areas of western Georgia has disappeared during the past 100 years because of the agricultural development of the land and urbanization. The large majority of the forests that covered the Colchis plain are now virtually non-existent with the exception of the regions that are included in the national parks and reserves (e.g. Lake Paliastomi area). At present, the forest cover generally remains outside of the low-lying areas and is mainly located along the foothills and the mountains. Western Georgia's forests consist mainly of deciduous trees below 600 metres (1,969 ft) above sea level and contain species such as oak, hornbeam, beech, elm, ash, and chestnut. Evergreen species such as box may also be found in many areas. Ca. 1000 of all 4000 higher plants of Georgia are endemic to this country.[228]

The west-central slopes of the Meskheti Range in Ajaria as well as several locations in Samegrelo and Abkhazia are covered by temperate rain forests. Between 600–1,000 metres (1,969–3,281 ft) above sea level, the deciduous forest becomes mixed with both broad-leaf and coniferous species making up the plant life. The zone is made up mainly of beech, spruce, and fir forests. From 1,500–1,800 metres (4,921–5,906 ft), the forest becomes largely coniferous. The tree line generally ends at around 1,800 metres (5,906 ft) and the alpine zone takes over, which in most areas, extends up to an elevation of 3,000 metres (9,843 ft) above sea level.[227] Eastern Georgia's landscape (referring to the territory east of the Likhi Range) is considerably different from that of the west, although, much like the Colchis plain in the west, nearly all of the low-lying areas of eastern Georgia including the Mtkvari and Alazani River plains have been deforested for agricultural purposes. The general landscape of eastern Georgia comprises numerous valleys and gorges that are separated by mountains. In contrast with western Georgia, nearly 85 per cent of the forests of the region are deciduous. Coniferous forests only dominate in the Borjomi Gorge and in the extreme western areas. Out of the deciduous species of trees, beech, oak, and hornbeam dominate. Other deciduous species include several varieties of maple, aspen, ash, and hazelnut.[227]

At higher elevations above 1,000 metres (3,281 ft) above sea level (particularly in the Tusheti, Khevsureti, and Khevi regions), pine and birch forests dominate. In general, the forests in eastern Georgia occur between 500–2,000 metres (1,640–6,562 ft) above sea level, with the alpine zone extending from 2,000–2,300 to 3,000–3,500 metres (6,562–7,546 to 9,843–11,483 ft). The only remaining large, low-land forests remain in the Alazani Valley of Kakheti.[227]

Climate

The climate of Georgia is extremely diverse, considering the nation's small size. There are two main climatic zones, roughly corresponding to the eastern and western parts of the country. The Greater Caucasus Mountain Range plays an important role in moderating Georgia's climate and protects the nation from the penetration of colder air masses from the north. The Lesser Caucasus Mountains partially protect the region from the influence of dry and hot air masses from the south.[229]

Much of western Georgia lies within the northern periphery of the humid subtropical zone with annual precipitation ranging from 1,000–2,500 mm (39–98 in), reaching a maximum during the Autumn months. The climate of the region varies significantly with elevation and while much of the lowland areas of western Georgia are relatively warm throughout the year, the foothills and mountainous areas (including both the Greater and Lesser Caucasus Mountains) experience cool, wet summers and snowy winters (snow cover often exceeds 2 metres or 6 feet 7 inches in many regions).[229]

Eastern Georgia has a transitional climate from humid subtropical to continental. The region's weather patterns are influenced both by dry Caspian air masses from the east and humid Black Sea air masses from the west. The penetration of humid air masses from the Black Sea is often blocked by mountain ranges (Likhi and Meskheti) that separate the eastern and western parts of the nation.[227] The wettest periods generally occur during spring and autumn, while winter and summer months tend to be the driest. Much of eastern Georgia experiences hot summers (especially in the low-lying areas) and relatively cold winters. As in the western parts of the nation, elevation plays an important role in eastern Georgia where climatic conditions above 1,500 metres (4,921 ft) are considerably colder than in the low-lying areas.[227]

Biodiversity

Because of its high landscape diversity and low latitude, Georgia is home to about 5,601 species of animals, including 648 species of vertebrates (more than 1% of the species found worldwide) and many of these species are endemics.[230] A number of large carnivores live in the forests, namely Brown bears, wolves, lynxes and Caucasian Leopards. The common pheasant (also known as the Colchian Pheasant) is an endemic bird of Georgia which has been widely introduced throughout the rest of the world as an important game bird. The species number of invertebrates is considered to be very high but data is distributed across a high number of publications. The spider checklist of Georgia, for example, includes 501 species.[231] The Rioni River may contain a breeding population of the critically endangered bastard sturgeon.[232]

Slightly more than 6,500 species of fungi, including lichen-forming species, have been recorded from Georgia,[233][234] but this number is far from complete. The true total number of fungal species occurring in Georgia, including species not yet recorded, is likely to be far higher, given the generally accepted estimate that only about seven per cent of all fungi worldwide have so far been discovered.[235] Although the amount of available information is still very small, a first effort has been made to estimate the number of fungal species endemic to Georgia, and 2,595 species have been tentatively identified as possible endemics of the country.[236] 1,729 species of plants have been recorded from Georgia in association with fungi.[234] According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, there are 4,300 species of vascular plants in Georgia.[237]

Georgia is home to four ecoregions: Caucasus mixed forests, Euxine-Colchic deciduous forests, Eastern Anatolian montane steppe, and Azerbaijan shrub desert and steppe.[238] It had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 7.79/10, ranking it 31st globally out of 172 countries.[239]

Economy

Archaeological research demonstrates that Georgia has been involved in commerce with many lands and empires since ancient times, largely due its location on the Black Sea and later on the historical Silk Road. Gold, silver, copper and iron have been mined in the Caucasus Mountains. Georgian wine making is a very old tradition and a key branch of the country's economy. The country has sizeable hydropower resources.[240] Throughout Georgia's modern history agriculture and tourism have been principal economic sectors, because of the country's climate and topography.

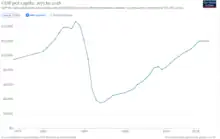

For much of the 20th century, Georgia's economy was within the Soviet model of command economy. Since the fall of the USSR in 1991, Georgia embarked on a major structural reform designed to transition to a free market economy. As with all other post-Soviet states, Georgia faced a severe economic collapse. The civil war and military conflicts in South Ossetia and Abkhazia aggravated the crisis. The agriculture and industry output diminished. By 1994 the gross domestic product had shrunk to a quarter of that of 1989.[241]

Since the early 21st century visible positive developments have been observed in the economy of Georgia. In 2007, Georgia's real GDP growth rate reached 12 per cent, making Georgia one of the fastest-growing economies in Eastern Europe. Georgia has become more integrated into the global trading network: its 2015 imports and exports account for 50% and 21% of GDP respectively.[242] Georgia's main imports are vehicles, ores, fossil fuels and pharmaceuticals. Main exports are ores, ferro-alloys, vehicles, wines, mineral waters and fertilizers.[243][244] The World Bank dubbed Georgia "the number one economic reformer in the world" because it has in one year improved from rank 112th to 18th in terms of ease of doing business,[245] and by 2020 further improved its position to 6th in the world.[246] As of 2021, it ranked 12th in the world for economic freedom. In 2019, Georgia ranked 61st on the Human Development Index (HDI). Between 2000 and 2019, Georgia's HDI score improved by 17.7%.[247] Of factors contributing to HDI, education had the most positive influence[248] as Georgia ranks in the top quintile in terms of education.

Georgia is developing into an international transport corridor through Batumi and Poti ports, Baku–Tbilisi–Kars Railway line, an oil pipeline from Baku through Tbilisi to Ceyhan, the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan pipeline (BTC) and a parallel gas pipeline, the South Caucasus Pipeline.[249]

Since coming to power the Saakashvili administration accomplished a series of reforms aimed at improving tax collection. Among other things a flat income tax was introduced in 2004.[250] As a result, budget revenues have increased fourfold and a once large budget deficit has turned into a surplus.[251][252]

As of 2001, 54 per cent of the population lived below the national poverty line but by 2006 poverty decreased to 34 per cent and by 2015 to 10.1 per cent.[253] In 2015, the average monthly income of a household was 1,022.3₾ (about $426).[254] 2015 calculations place Georgia's nominal GDP at US$13.98 billion.[255] Georgia's economy is becoming more devoted to services (as of 2016, representing 59.4 per cent of GDP), moving away from the agricultural sector (6.1 per cent).[256] Since 2014, unemployment has been gradually decreasing each year but remained in double digits and worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic.[257] A perception of economic stagnation led to a 2019 survey of 1,500 residents finding unemployment was considered a significant problem by 73% of respondents, with 49% reporting their income had decreased over the prior year.[258]

Georgia's telecommunications infrastructure is ranked the last among its bordering neighbours in the World Economic Forum's Network Readiness Index (NRI) – an indicator for determining the development level of a country's information and communication technologies. Georgia ranked number 58 overall in the 2016 NRI ranking,[259] up from 60 in 2015.[260] Georgia was ranked 63rd in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, down from 48th in 2019.[261][262][263][264]

Tourism

.jpg.webp)

Tourism is an increasingly significant part of the Georgian economy. In 2016, 2,714,773 tourists brought approximately US$2.16 billion to the country.[265] In 2019, the number of international arrivals reached a record high of 9.3 million people[266] with foreign exchange income in the year's first three quarters amounting to over US$3 billion. The country plans to host 11 million visitors by 2025 with annual revenues reaching US$6.6 billion.[267] According to the government, there are 103 resorts in different climatic zones in Georgia. Tourist attractions include more than 2,000 mineral springs, over 12,000 historical and cultural monuments, four of which are recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites (Bagrati Cathedral in Kutaisi and Gelati Monastery, historical monuments of Mtskheta, and Upper Svaneti).[268] Other tourist attractions are Cave City, Ananuri Castle/Church, Sighnaghi and Mount Kazbek. In 2018, more than 1.4 million tourists from Russia visited Georgia.[269]

Transport

.jpg.webp)

Today transport in Georgia is provided by rail, road, ferry, and air. Total length of roads in Georgia, excluding the occupied territories, is 21,110 kilometres (13,120 mi) and railways – 1,576 km (979 mi).[270] Positioned in the Caucasus and on the coast of the Black Sea, Georgia is a key country through which energy imports to the European Union from neighbouring Azerbaijan pass.

In recent years Georgia has invested large amounts of money in the modernization of its transport networks. The construction of new highways has been prioritized and, as such, major cities like Tbilisi have seen the quality of their roads improve dramatically; despite this however, the quality of inter-city routes remains poor and to date only one motorway-standard road has been constructed – the ს 1 (S1), the main east–west highway through the country.

The Georgian railways represent an important transport artery for the Caucasus, as they make up the largest proportion of a route linking the Black and Caspian Seas. In turn, this has allowed them to benefit in recent years from increased energy exports from neighbouring Azerbaijan to the European Union, Ukraine, and Turkey.[271] Passenger services are operated by the state-owned Georgian Railway whilst freight operations are carried out by a number of licensed operators. Since 2004 the Georgian Railways have been undergoing a rolling programme of fleet-renewal and managerial restructuring which is aimed at making the service provided more efficient and comfortable for passengers.[272] Infrastructural development has also been high on the agenda for the railways, with the key Tbilisi railway junction expected to undergo major reorganization in the near future.[273] Additional projects also include the construction of the economically important Kars–Tbilisi–Baku railway, which was opened on 30 October 2017 and connects much of the Caucasus with Turkey by standard gauge railway.[274][275]

Air and maritime transport is developing in Georgia, with the former mainly used by passengers and the latter for transport of freight. Georgia currently has four international airports, the largest of which is by far Tbilisi International Airport, hub for Georgian Airways, which offers connections to many large European cities. Other airports in the country are largely underdeveloped or lack scheduled traffic, although, as of late, efforts have been made to solve both these problems.[276] There are a number of seaports along Georgia's Black Sea coast, the largest and most busy of which is the Port of Batumi; whilst the town is itself a seaside resort, the port is a major cargo terminal in the Caucasus and is often used by neighbouring Azerbaijan as a transit point for making energy deliveries to Europe. Scheduled and chartered passenger ferry services link Georgia with Bulgaria,[277] Romania, Turkey and Ukraine.[278]

Demographics

Like most native Caucasian peoples, the Georgians do not fit into any of the main ethnic categories of Europe or Asia. The Georgian language, the most pervasive of the Kartvelian languages, is not Indo-European, Turkic, or Semitic. The present-day Georgian or Kartvelian nation is thought to have resulted from the fusion of aboriginal, autochthonous inhabitants with immigrants who moved into South Caucasus from the direction of Anatolia in remote antiquity.[280]

The population of Georgia totalled 3,688,647 as of 2022,[281][lower-alpha 3] a decrease from a figure of 3,713,804 of the previous census in October 2014.[282][lower-alpha 3] The population declined by 40,000 in 2021, a reversal of the trend towards stabilisation of the last decade and, for the first time since independence, the population was recorded to be below 3.7 million. According to the 2014 census, Ethnic Georgians form about 86.8 per cent of the population, while the remainder includes ethnic groups such as Abkhazians, Armenians, Assyrians, Azerbaijanis, Greeks, Jews, Kists, Ossetians, Russians, Ukrainians, Yezidis and others.[282][lower-alpha 3] The Georgian Jews are one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world. According to the 1926 census there were 27,728 Jews in Georgia.[283][lower-alpha 4] Georgia was also once home to significant ethnic German communities, numbering 11,394 according to the 1926 census.[283][lower-alpha 5] Most of them were deported during World War II.[286]

The 2014 census, carried out in collaboration with the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), found a population gap of approximately 700,000 compared to the 2014 data from the National Statistical Office of Georgia, Geostat, which was cumulatively built on the 2002 census. Consecutive research estimated the 2002 census to be inflated by 8 to 9 percent,[287] which affected the annually updated population estimates in subsequent years. One explanation put forward by UNFPA is that families of emigrants continued to list them in 2002 as residents for fear of losing certain rights or benefits. Also, the population registration system from birth to death was non-functional. It was not until around 2010 that parts of the system became reliable again. With the support of the UNFPA, the demographic data for the period 1994–2014 has been retro-projected.[288] On the basis of that back-projection, Geostat has corrected its data for these years.

The 1989 census recorded 341,000 ethnic Russians, or 6.3 per cent of the population,[289] 52,000 Ukrainians and 100,000 Greeks in Georgia.[290] The population of Georgia, including the breakaway regions, has declined by more than 1 million due to net emigration in the period 1990–2010.[291][290] Other factors in the population decline include birth-death deficits for the period 1995–2010 and the exclusion of Abkhazia and South Ossetia from the statistics. Russia received by far the most migrants from Georgia. According to United Nations data, this totalled 625,000 by 2000, declining to 450,000 by 2019.[292] Initially the out-migration was driven by non-Georgian ethnicities but increasing numbers of Georgians emigrated as well,[293] due to the war, the crisis-ridden 1990s, and the subsequent bad economic outlook. The 2010 Russian census recorded about 158,000 ethnic Georgians living in Russia,[294] with approximately 40,000 living in Moscow by 2014.[295] There were 184 thousand immigrants in Georgia in 2014 with most of them hailing from Russia (51.6%), Greece (8.3%), Ukraine (8.11%), Germany (4.3%), and Armenia (3.8%).[296][lower-alpha 3]

In the early 1990s, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, violent separatist conflicts broke out in the autonomous region of Abkhazia and Tskhinvali Region. Many Ossetians living in Georgia left the country, mainly to Russia's North Ossetia.[297] On the other hand, at least 160,000 Georgians left Abkhazia after the break-out of hostilities in 1993.[298] Of the Meskhetian Turks who were forcibly relocated in 1944, only a tiny fraction returned to Georgia as of 2008.[299]

The most widespread language group is the Kartvelian family, which includes Georgian, Svan, Mingrelian and Laz.[300][301][302][303][304][305] The official languages of Georgia are Georgian, with Abkhaz having official status within the autonomous region of Abkhazia. Georgian is the primary language of 87.7 per cent of the population, followed by 6.2 per cent speaking Azerbaijani, 3.9 per cent Armenian, 1.2 per cent Russian, and 1 per cent other languages.[306][lower-alpha 3] Azerbaijani once served as a lingua franca for communication among various nationalities inhabiting Eastern Caucasus.[285]

| Rank | Name | Administrative divisions of Georgia | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Tbilisi  Batumi |

1 | Tbilisi | Tbilisi | 1 108 717 | .jpg.webp) Kutaisi  Rustavi | ||||

| 2 | Batumi | Adjara | 152 839 | ||||||

| 3 | Kutaisi | Imereti | 147 635 | ||||||

| 4 | Rustavi | Kvemo Kartli | 125 103 | ||||||

| 5 | Gori | Shida Kartli | 48 143 | ||||||

| 6 | Zugdidi | Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti | 42 998 | ||||||

| 7 | Poti | Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti | 41,465 | ||||||

| 8 | Sokhumi | Abkhazia | 39,100[lower-alpha 6] | ||||||

| 9 | Khashuri | Shida Kartli | 33 627 | ||||||

| 10 | Tskhinvali | Shida Kartli | 30,000[lower-alpha 6] | ||||||

Religion

Main religions (2014)[307][lower-alpha 3]

Today 83.4 per cent of the population practices Eastern Orthodox Christianity, with the majority of these adhering to the national Georgian Orthodox Church.[308][lower-alpha 3] The Georgian Orthodox Church is one of the world's most ancient Christian Churches, and claims apostolic foundation by Saint Andrew.[309] In the first half of the 4th century, Christianity was adopted as the state religion of Iberia (present-day Kartli, or eastern Georgia), following the missionary work of Saint Nino of Cappadocia.[310][311] The Church gained autocephaly during the early Middle Ages; it was abolished during the Russian domination of the country, restored in 1917 and fully recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople in 1989.[312]

The special status of the Georgian Orthodox Church is officially recognized in the Constitution of Georgia and the Concordat of 2002, although religious institutions are separate from the state.

Religious minorities of Georgia include Muslims (10.7 per cent), Armenian Christians (2.9 per cent) and Roman Catholics (0.5 per cent).[308][lower-alpha 3] 0.7 per cent of those recorded in the 2014 census declared themselves to be adherents of other religions, 1.2 per cent refused or did not state their religion and 0.5 per cent declared no religion at all.[308]

Islam is represented by both Azerbaijani Shia Muslims (in the south-east), ethnic Georgian Sunni Muslims in Adjara, and Laz-speaking Sunni Muslims as well as Sunni Meskhetian Turks along the border with Turkey. In Abkhazia, a minority of the Abkhaz population is also Sunni Muslim. There are also smaller communities of Greek Muslims (of Pontic Greek origin) and Armenian Muslims, both of whom are descended from Ottoman-era converts to Turkish Islam from Eastern Anatolia who settled in Georgia following the Lala Mustafa Pasha's Caucasian campaign that led to the Ottoman conquest of the country in 1578. Georgian Jews trace the history of their community to the 6th century BC; their numbers have dwindled in the last decades due to high levels of immigration to Israel.[313]

Despite the long history of religious harmony in Georgia,[314] there have been instances of religious discrimination and violence against "nontraditional faiths", such as Jehovah's Witnesses, by followers of the defrocked Orthodox priest Basil Mkalavishvili.[315]

In addition to traditional religious organizations, Georgia retains secular and irreligious segments of society (0.5 per cent),[316] as well as a significant portion of religiously affiliated individuals who do not actively practice their faith.[317]

Education

The education system of Georgia has undergone sweeping, though controversial, modernisation since 2004.[318][319] Education in Georgia is mandatory for all children aged 6–14.[320] The school system is divided into elementary (six years; ages 6–12), basic (three years; ages 12–15), and secondary (three years; ages 15–18), or alternatively vocational studies (two years). Access to higher education is given to students who have gained a secondary school certificate. Only those students who have passed the Unified National Examinations may enroll in a state-accredited higher education institution, based on ranking of the scores received at the exams.[321]

Most of these institutions offer three levels of study: a bachelor's programme (three to four years); a master's programme (two years), and a doctoral programme (three years). There is also a certified specialist's programme that represents a single-level higher education programme lasting from three to six years.[320][322] As of 2016, 75 higher education institutions are accredited by the Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia.[323] Gross primary enrolment ratio was 117 per cent for the period of 2012–2014, the 2nd highest in Europe after Sweden.[324]

Tbilisi has become the main artery of the Georgian educational system, particularly since the creation of the First Georgian Republic in 1918 permitted the establishment of modern, Georgian-language educational institutions. Tbilisi is home to several major institutions of higher education in Georgia, notably the Tbilisi State Medical University, which was founded as Tbilisi Medical Institute in 1918, and the Tbilisi State University (TSU), which was established in 1918 and remains the oldest university in the entire Caucasus region.[325] The number of faculty and staff (collaborators) at TSU is approximately 5,000, with over 35,000 students enrolled. The following four universities are also located in Tbilisi: Georgian Technical University,[326] which is Georgia's main and largest technical university, The University of Georgia (Tbilisi),[327] as well as Caucasus University[328] and Free University of Tbilisi.[329]

Culture

%252C_1300.jpg.webp)