Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic

The Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (TDFR;[lower-alpha 1] 22 April – 28 May 1918)[lower-alpha 2] was a short-lived state in the Caucasus that included most of the territory of the present-day Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia, as well as parts of Russia and Turkey. The state lasted only for a month before Georgia declared independence, followed shortly after by Armenia and Azerbaijan.

Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1918–1918 | |||||||||||||

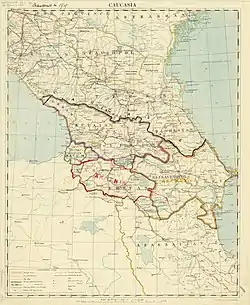

A 1918 map of the Caucasus by the British Army. The highlighted sections show the successor states of the TDFR, which claimed roughly the same territory.[1] | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Tiflis | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Georgian Azerbaijani Armenian Russian | ||||||||||||

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic under a provisional government | ||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Seim | |||||||||||||

• 1918 | Nikolay Chkheidze | ||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||||

• 1918 | Akaki Chkhenkeli | ||||||||||||

| Legislature | Transcaucasian Seim | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Russian Revolution | ||||||||||||

| 2 March 1917 | |||||||||||||

• Federation proclaimed | 22 April 1918 | ||||||||||||

• Georgia declares independence | 26 May 1918 | ||||||||||||

• Independence of Armenia and Azerbaijan | 28 May 1918 | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Transcaucasian ruble (ru)[2] | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkey | ||||||||||||

The region that formed the TDFR had been part of the Russian Empire. As the empire dissolved during the 1917 February Revolution and a provisional government took over, a similar body, called the Special Transcaucasian Committee (Ozakom), did the same in the Caucasus. After the October Revolution and rise of the Bolsheviks in Russia, the Transcaucasian Commissariat replaced the Ozakom. In March 1918, as the First World War continued, the Commissariat initiated peace talks with the Ottoman Empire, which had invaded the region, but that broke down quickly as the Ottomans refused to accept the authority of the Commissariat. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which ended Russia's involvement in the war, conceded parts of the Transcaucasus to the Ottoman Empire, which pursued its invasion to take control of the territory. Faced with this imminent threat, on 22 April 1918 the Commissariat dissolved itself and established the TDFR as an independent state. A legislature, the Seim, was formed to direct negotiations with the Ottoman Empire, which had immediately recognized the state.

Diverging goals of the three major groups (Armenians, Azerbaijanis,[lower-alpha 3] and Georgians) quickly jeopardized the TDFR's existence. Peace talks again broke down and, facing a renewed Ottoman offensive in May 1918, Georgian delegates in the Seim announced that the TDFR was unable to continue, and declared the Democratic Republic of Georgia independent on 26 May. With the Georgians no longer part of the TDFR, the Republic of Armenia and Azerbaijan Democratic Republic each declared themselves independent on 28 May, ending the federation. Owing to its short existence, the TDFR has been largely ignored in the national historiographies of the region and has been given consideration only as the first stage towards independent states.

History

Background

Most of the South Caucasus had been absorbed by the Russian Empire in the first half of the nineteenth century.[8] A Caucasian Viceroyalty had originally been established in 1801 to allow for direct Russian rule, and over the next several decades local autonomy was reduced and Russian control was further consolidated, the Viceroyalty gaining greater power in 1845.[9] Tiflis (now Tbilisi), which had been the capital of the Georgian Kingdom of Kartli-Kakheti, became the seat of the viceroy and the de facto capital of the region.[10] The South Caucasus was overwhelmingly rural: aside from Tiflis the only other city of significance was Baku,[lower-alpha 4][11] which grew in the late nineteenth century as the region began exporting oil and became a major economic hub.[12] Ethnically the region was highly diverse. The three major local groups were Armenians, Azerbaijanis, and Georgians; Russians had also established themselves after the Russian Empire absorbed the area.[13]

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the Caucasus became a major theatre, the Russian and Ottoman Empires fighting each other in the region.[14] The Russians won several battles and penetrated deep into Ottoman territory. However, they were concerned that the local population, who were mostly Muslims, would continue to follow the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed V and disrupt the Russian forces, as he was also the caliph, the spiritual leader of Islam.[15] Both sides also wanted to use the Armenian population, who lived across the border, to their advantage and foment uprisings.[16] After military defeats, the Ottoman government turned against the Armenians, and initiated a genocide by 1915, in which around 1 million Armenians were killed.[17][18]

The 1917 February Revolution saw the demise of the Russian Empire and the establishment of a provisional government in Russia. The Viceroy of the Caucasus, Grand Duke Nicholas, initially expressed his support for the new government, yet he was forced to resign his post as imperial power eroded.[19] The provisional government created a new temporary authority, the Special Transcaucasian Committee (known by its Russian abbreviation, Ozakom[lower-alpha 5]) on 22 March 1917 [O.S. 9 March]. It was composed of Caucasian representatives to the Duma (Russian legislature) and other local leaders, it was meant to serve as a "collective viceroyalty", and had representatives from the ethnic groups of the region.[21][22] Much like in Petrograd,[lower-alpha 6] a dual power system was established, the Ozakom competing with soviets.[lower-alpha 7][24] With little support from the government in Petrograd, the Ozakom had trouble establishing its authority over the soviets, most prominently the Tiflis Soviet.[25]

Transcaucasian Commissariat

News of the October Revolution, which brought the Bolsheviks to power in Petrograd on 7 November 1917 [O.S. 25 October], reached the Caucasus the following day. The Tiflis Soviet met and declared their opposition to the Bolsheviks. Three days later the idea of an autonomous local government was first expressed by Noe Jordania, a Georgian Menshevik, who argued that the Bolshevik seizure of power was illegal and that the Caucasus should not follow their directives, and wait until order was restored.[26] A further meeting of representatives from the Tiflis Soviet, the Ozakom, and other groups on 28 November [O.S. 15 November] decided to end the Ozakom and replace it with a new body, the Transcaucasian Commissariat, which would not be subservient to the Bolsheviks. Composed of representatives from the four major ethnic groups in the region (Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Georgians, and Russians) it replaced the Ozakom as the government of the South Caucasus, and was set to serve in that role until the Russian Constituent Assembly could meet in January 1918. Evgeni Gegechkori, a Georgian, was named the president and Commissar of External Affairs of the Commissariat.[27] The other commissariats were split between Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Georgians, and Russians.[28] Formed with the express purpose of being a caretaker government, the Commissariat was not able to govern strongly: it was dependent on national councils, formed around the same time and based on ethnic lines, for military support and was effectively powerless to enforce any laws it passed.[29]

With Russian and Ottoman forces still nominally engaged in the region, a temporary ceasefire, the Armistice of Erzincan, was signed on 18 December 1917 [O.S. 5 December].[30] With the fighting paused, on 16 January 1918 [O.S. 3 January], Ottoman diplomats invited the Commissariat to join the peace talks in Brest-Litovsk, where the Bolsheviks were negotiating an end to the war with the Central Powers. As the Commissariat did not want to act independently of Russia, they did not answer the invitation and thus did not participate in the peace talks there.[31] Two days later, on 18 January [O.S. 5 January], the Constituent Assembly had its first and only meeting, broken up by the Bolsheviks, thereby effectively consolidating their power in Russia.[32] This confirmed for the Commissariat that they would not be able to work with the Bolsheviks in any serious capacity, and so they began to form a more formal government.[33] The ceasefire between the Ottoman Empire and the Commissariat lasted until 30 January [O.S. 17 January], when the Ottoman army launched a new offensive into the Caucasus, claiming it was to retaliate against sporadic attacks by Armenian militias on the Muslim population in occupied Ottoman territory.[34] With Russian forces largely withdrawn from the front, the Commissariat realized that they would not be able to resist a full-scale advance by the Ottoman forces, and so on 23 February agreed to start a new round of peace talks.[30]

Seim

The idea to establish a Transcaucasian legislative body had been discussed since November 1917, though it had not been acted on at that time.[35] With the dissolution of the Constituent Assembly in January, it became apparent to the leaders of the Commissariat that ties with Russia had been all but severed. With no desire to follow the lead of the Bolsheviks, the Commissariat agreed to establish their own legislative body so that the Transcaucasus could have a legitimate government and negotiate with the Ottoman Empire more properly. Thus on 23 February they established the "Seim" ("legislature") in Tiflis.[36]

No election was held for the deputies; instead, the results for the Constituent Assembly election were used, the electoral threshold being lowered to one-third of that used for the Constituent Assembly to allow more members to join, which allowed smaller parties to be represented.[lower-alpha 8][37] Nikolai Chkheidze, a Georgian Menshevik, was named the chairman.[38] Ultimately the Seim comprised ten different parties. Three dominated, each representing one major ethnic group: the Georgian Mensheviks and Azerbaijani Musavat party each had 30 members, and the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (Dashnaktsutyun) had 27 members.[37] The Bolsheviks boycotted the Seim, asserting that the only legitimate government for Russia (including Transcaucasia) was the Bolshevik-controlled Council of People's Commissars (known by its Russian acronym, Sovnarkom).[lower-alpha 9][36]

From the outset, the Seim faced challenges to its authority. With a diverse ethnic and political makeup and no clear status to its authority, there was conflict both within its chambers and outside.[39] It was largely dependent on national councils, represented by the three main ethnic groups, and was unable to proceed without their consent.[1] Thus the Ottoman offer to renew peace talks and a willingness to meet in Tiflis, where the Seim was based, was refused, as the Seim felt it would only showcase the internal disagreements taking place. Instead they agreed to travel to Trabzon, in northeast Anatolia.[40]

Trabzon peace conference

A delegation representing the Seim was scheduled to depart for Trabzon on 2 March, but that day it was announced that the peace talks at Brest-Litovsk had concluded, and the Russians would sign a peace treaty.[41] Contained within the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was the agreement that the Russians would give up large swaths of land to the Ottoman Empire, including major regions in the Transcaucasus: the territories of Ardahan, Batum Oblast, and Kars Oblast, all of which had been annexed by Russia after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878.[42] With this sudden development, the delegation postponed leaving as they had to reconsider their stance.[43] As the Transcaucasus had not been part of the negotiations at Brest-Litovsk, they sent messages to several governments around the world, stating as they were not a party in the peace talks they would not honor the treaty and would not evacuate the territories.[44] The delegation would finally depart on 7 March and arrive at Trabzon the next day.[45] On arrival, the delegation, comprising ten delegates and another fifty guards, was held up as the guards were asked to disarm. The unusually large delegation was made up of individuals selected to represent the diverse ethnic groups and political factions that composed the Seim;[46] on their arrival an Ottoman official quipped that "[i]f this was the entire population of Transcaucasia, it was indeed very small; if, however, it was only a delegation, it was much too large."[44]

While the delegates waited for the conference in Trabzon to begin, the head of the Ottoman Third Army, Vehib Pasha, sent a request on 10 March to Evgeny Lebedinskii, a former Russian general who had begun to follow orders from the Commissariat, to evacuate the Ardahan, Batum, and Kars areas, as stipulated by the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Vehib also told Ilia Odishelidze, who was also taking orders from the Commissariat, that in light of attacks by Armenian forces on the population near Erzurum, Ottoman forces would have to advance to keep the peace, warning that any hostile reply would be met with force. These requests were replied to directly by Chkheidze as Chairman of the Seim, who noted that the Transcaucasus had sent a delegation to Trabzon to negotiate peace, and that as the Seim no longer recognized Russian authority they would not acknowledge the provisions of Brest-Litovsk.[47][48] On 11 March the Ottoman army began their attack on Erzurum and with little hope for success, the mostly Armenian defenders evacuated less than twenty-four hours later.[49]

The Trabzon Peace Conference opened on 14 March. At the first session, the lead Ottoman delegate, Rauf Bey, asked the Transcaucasian delegation whom they represented. Akaki Chkhenkeli, the head of the Transcaucasian delegation, was unable to give a proper response as it was not clear to him or his associates who they represented. When the question was repeated two days later, Rauf also asked Chkhenkeli to clarify the make-up of their state, to determine if it qualified as one under international law. Chkhenkeli clarified that since the October Revolution, the central authority had ceased to exist in Transcaucasia. An independent government had been formed and that since it had acted like a state when it discussed the invitation to the Brest-Litovsk peace talks, it qualified as a sovereign state, even if independence had not been explicitly proclaimed.[50] Rauf refuted the argument, asserting that the Sovnarkom had authority over all of Russia and even though Ottoman representatives had sent messages to the Commissariat to join the talks at Brest-Litovsk, that did not confer recognition. Finally, Rauf stated that the Ottoman delegation was at Trabzon only to resolve some economic and commercial issues that had not been settled at Brest-Litovsk. Chkhenkeli and his fellow delegates had little option but to request a short recess so they could message the Seim and determine how to proceed.[51]

Formation

Renewed Ottoman invasion

During the recess at Trabzon, the Ottoman forces continued their advance into the Transcaucasian territory, crossing the 1914 border with the Russian Empire by the end of March.[52] The Seim debated the best course of action; a majority of the delegates favored a political solution. On 20 March the Ottoman delegates offered that the Seim could only return to negotiations if they declared independence, thereby confirming that Transcaucasus was no longer part of Russia.[53] The idea of independence had arisen before, the Georgians having discussed it in depth in preceding years; it was decided against as the Georgian leadership felt the Russians would not approve it and the Menshevik political ideology leaned away from nationalism.[54]

By 5 April, Chkhenkeli accepted the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk as a basis for further negotiations and urged the Transcaucasian Seim to accept this position.[55] He initially asked that Batum remain part of the Transcaucasus, arguing that as the major port in the region it was an economic necessity. The Ottomans refused the proposal, making it clear that they would only accept the terms of Brest-Litovsk, to which Chkhenkeli conceded.[56] Acting on his own accord, on 9 April Chkhenkeli agreed to negotiate further based on the terms set out, though requested that representatives from the other Central Powers participate in the talks. Rauf replied that such a request could only be considered if the Transcaucasus were an independent state.[57]

Tired of fruitless negotiations and realizing that the contested territories could be occupied by force, Ottoman officials issued an ultimatum to the defenders in Batum, ordering it evacuated by 13 April.[58] While Chkhenkeli was receptive to the loss of Batum, recognizing its importance but accepting that it was part of the terms at Brest-Litovsk, the Georgian members of the Seim were adamant about keeping the city, Gegechkori noting that it could be defended quite easily.[57][59] Irakli Tsereteli, a Georgian Menshevik, gave an impassioned speech calling for the defense of the city and asked the Seim to denounce the Brest-Litovsk treaty altogether. Armenian delegates had long been in support of fighting the Ottoman Empire, a response to the 1915 genocide and continued attacks on Armenian civilians, while only the Azerbaijanis resisted going to war, as they were reluctant to fight fellow Muslims.[60] Azerbaijanis were outvoted and on 14 April the Seim declared war on the Ottoman Empire.[61][62] Immediately after the voting finished, Tsereteli and Jordania left to join the defense of Batum, while the delegation in Trabzon was ordered to return to Tiflis immediately.[63] Some Azerbaijani delegates defied this order and remained there, seeking potential negotiation, though nothing came of this.[64]

Establishment

The military superiority of the Ottoman forces became apparent right away.[65] They occupied Batum on 14 April, with little resistance. They also attacked Kars, but a force of 3,000 Armenian soldiers, with artillery support, held the city until it was evacuated on 25 April.[66] Having captured most of their claimed territory and unwilling to lose more soldiers, the Ottoman delegates offered another truce on 22 April and waited for the Transcaucasians to reply.[67]

In the face of Ottoman military superiority, the Georgian National Council decided that the only option was for Transcaucasia to declare itself an independent state.[68] The idea was debated in the Seim on 22 April, the Georgians leading the debate, noting that the Ottoman representatives had agreed to resume peace talks provided that the Transcaucasus would meet them as an independent state.[69] The choice to move forward was not unanimous initially: the mostly Armenian Dashnaks felt that the best option at the time was to stop the Ottoman military's advance, though they were reluctant to give up so much territory, while the Musavats, who represented Azerbaijani interests, were still hesitant to fight fellow Muslims, but conceded that independence was the only way to ensure the region would not be divided by foreign states. The only major opposition came from the Socialist Revolutionary Party, when one of their representatives, Lev Tumanov, argued that the people of Transcaucasia did not support such an action. He also argued that while the Musavats claimed their driving force was "conscience not fear", it was in reality "fear and not conscience". He concluded that they would all regret this act.[70]

When the debate finished, Davit Oniashvili, an ethnic Georgian Menshevik, proposed the motion for the Seim "to proclaim Transcaucasia an independent democratic federative republic".[71] Some deputies left the chamber as they did not want to vote in favor of the matter, so the motion passed with few dissents.[72] The new republic, the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (TDFR), immediately sent a message to Vehib Pasha announcing this development and expressing their will to accept the provisions of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, and surrendered Kars to the Ottoman Empire.[73] The Ottoman Empire recognized the TDFR on 28 April.[74] Despite this recognition, the Ottomans continued their advance into Transcaucasian territory and shortly after occupied both Erzerum[lower-alpha 10] and Kars.[76]

Independence

Upon its establishment, the TDFR had no cabinet to lead the new government. The Commissariat had been dissolved when independence was declared, and Gegechkori refused to continue in a leadership position, feeling he had lost support to do so. Though it had been agreed during the Seim debates that Chkhenkeli would take up the role of prime minister, he refused to serve in a caretaker position until a new cabinet could be formed. The cabinet was not finalized until 26 April, so for three days the TDFR effectively had no executive.[72] With pressing needs to attend to, Chkhenkeli took up his role as prime minister. He ordered the Armenian forces to cease fighting and also requested Vehib to meet him for peace negotiations in Batum, the location deliberately chosen so that he could travel to Tiflis if necessary, something that was not possible from Trabzon.[77]

Upset at Chkhenkeli's actions over the previous days, namely the evacuation of Kars, the Dashnaks initially refused to join the cabinet. They negotiated with the Mensheviks but relented when the latter warned they would only support Chkhenkeli or Hovhannes Kajaznuni, an Armenian. The Mensheviks knew that electing Kajaznuni would give the perception that the TDFR intended to keep fighting to defend Armenian territory, and it was feared that this would see the Azerbaijanis leave the federation and make it easier for Ottoman forces to threaten the rest of Armenia, a proposition the Dashnaks were not eager to endorse.[78] The cabinet was confirmed by the Seim on 26 April, consisting of thirteen members. Chkhenkeli, aside from being prime minister, assumed foreign minister's office, the remaining positions being split among Armenians (four), Azerbaijanis (five), and Georgians (three).[79] Azerbaijanis and Georgians took up the leading positions in the cabinet, an act that historian Firuz Kazemzadeh said revealed as "the relationship of forces in Transcaucasia" at the time.[74] In his inaugural address to the Seim, Chkhenkeli announced that he would work to ensure all citizens had equality and to establish borders for the TDFR that were based on agreement with their neighbors.[80] He further laid out a platform with five main points: write a constitution; delineate borders; end the war; combat counter-revolution and anarchy; and land reform.[74]

A new peace conference was convened at Batum on 11 May, with both Chkhenkeli and Vehib in attendance.[81] Before the conference, Chkhenkeli repeated his request to have the other Central Powers present, which the Ottoman delegates ignored.[82] Both sides invited observers: the TDFR brought a small German contingent, led by General Otto von Lossow, while the Ottoman delegates had representatives from the Mountainous Republic of the Northern Caucasus, an unrecognized state they were backing. Chkhenkeli wished to proceed on the basis of the Brest-Litovsk terms, but this was refused by the Ottoman delegation, led by Halil Bey, the Ottoman minister of justice. Halil Bey argued that as the two states were in conflict, the Ottoman would no longer recognize Brest-Litovsk and instead presented Chkhenkeli with a duly prepared draft treaty.[83]

The treaty contained twelve articles which called for the Ottoman Empire to be ceded not only the oblasts of Kars and Batum, but also the uezds of Akhalkalaki, Akhaltsikhe, Surmalu, and large parts of the Alexandropol, Erivan, and Etchmiadzin, mainly along the course of the Kars–Julfa railway. The territory named would effectively bring all of Armenia into the Ottoman Empire.[84] The railway was desired as the Ottoman forces sought a fast route to North Persia, where they were fighting the British forces in the Persian Campaign, though historian Richard G. Hovannisian has suggested that the real reason was to allow them a means to reach Baku and access the oil production around the city.[85]

Giving the TDFR several days to consider their options, the Ottoman forces resumed their military advances into Armenia on 21 May. They engaged the Armenians at the battles of Bash Abaran, Sardarapat and Kara Killisse, but could not defeat the Armenians decisively. As a result, their advance slowed down, and eventually, they were forced to retreat.[86][87]

Dissolution

German intervention

By 22 May the Ottoman forces, split into two groups, were 40 km (25 mi) from Erevan and 120 km (75 mi) from Tiflis.[88] With this threat, the TDFR reached out to Von Lossow and the Germans in hopes of securing their help and protection. Von Lossow had previously offered to mediate between the TDFR and the Ottoman Empire on 19 May, though this had not led to any progress.[89] While the German and Ottoman Empires were nominally allies, the relationship had deteriorated in the preceding months, as the German public had not approved of reports that the Ottoman government was massacring Christians, nor did the German government appreciate the Ottoman army's advance into territory not agreed to at Brest-Litovsk.[90] The Germans also had their own strategic interests in the Caucasus: they wanted both a potential path to attack British India and access to raw materials in the region, both of which could be blocked by the Ottomans.[91]

With the Armenians fighting the Ottoman forces and the Azerbaijanis having their own issues with Bolsheviks controlling Baku, the Georgians concluded that they had no future in the TDFR.[92] On 14 May Jordania went to Batum to request German assistance to help secure Georgian independence. He returned to Tiflis on 21 May and expressed confidence that Georgia could become independent.[93] The Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian representatives from the Seim met on 21 May to discuss the future of the TDFR and agreed that it was not likely to last much longer. The next day the Georgians met alone and resolved that independence was their only logical choice.[92] Jordania and Zurab Avalishvili drafted a declaration of independence on 22 May, before Jordania left again for Batum to meet Von Lossow.[94] On 24 May Von Lossow replied that he was only authorized to work with the TDFR as a whole; as it was becoming apparent that it would not last long, he would have to leave Trabzon and consult with his government on how to proceed further.[95]

Break-up

On 26 May Tsereteli gave two speeches in the Seim. In the first, he explained that the TDFR was unable to continue as there was a lack of unity among the people and that ethnic strife led to a division of action in regards to the Ottoman invasion. In his second speech, Tsereteli blamed the Azerbaijanis for failing to support the defense of the TDFR and declared that as the federation had failed it was time for Georgia to proclaim itself independent.[96] At 15:00 the motion was passed: "Because on the questions of war and peace there arose basic differences among the peoples who had created the Transcaucasian Republic, and because it became impossible to establish one authoritative order speaking in the name of all Transcaucasia, the Seim certifies the fact of the dissolution of Transcaucasia and lays down its powers."[97] Most delegates left the chamber, leaving only the Georgians, who were shortly joined by members of the Georgian National Council. Jordania then read the Georgian declaration of independence and proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Georgia.[98] This was followed two days later with an Armenian declaration of independence, followed quickly by Azerbaijan doing the same, creating the Republic of Armenia and Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, respectively.[99] All three newly independent states signed a peace treaty with the Ottoman Empire on 4 June, effectively ending that conflict.[100] Armenia then later engaged in brief wars with both Azerbaijan (1918–1920) and Georgia (December 1918) to determine its final borders.[101]

Legacy

As the TDFR lasted only a month, it has had a limited legacy, and the historical scholarship on the topic is limited.[102] Historians Adrian Brisku and Timothy K. Blauvelt have noted that it "seemed both to the actors at the time and to later scholars of the region to be unique, contingent, and certainly unrepeatable."[103] Stephen F. Jones stated it was "the first and last attempt at an independent Transcaucasian union",[104] while Hovannisian noted that the actions of the TDFR during its short existence demonstrated that it "was not independent, democratic, federative, or a republic".[72]

Under Bolshevik rule, the three successor states would be forcibly reunited within the Soviet Union as the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic. This state lasted from 1922 to 1936 before being broken up again into three union republics: the Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian Soviet Socialist Republics.[105] Within the modern states of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, the TDFR is largely ignored in their respective national historiography, given consideration only as the first stage towards their own independent states.[106]

Government

Cabinet

| Portfolio | Minister[79] |

|---|---|

| Prime Minister | Akaki Chkhenkeli |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | Akaki Chkhenkeli |

| Minister of the Interior | Noe Ramishvili |

| Minister of Finance | Alexander Khatisian |

| Minister of Transportation | Khudadat bey Malik-Aslanov |

| Minister of Justice | Fatali Khan Khoyski |

| Minister of War | Grigol Giorgadze |

| Minister of Agriculture | Noe Khomeriki |

| Minister of Education | Nasib bey Yusifbeyli |

| Minister of Commerce and Industry | Mammad Hasan Hajinski |

| Minister of Supplies | Avetik Saakian |

| Minister of Social Welfare | Hovhannes Kajaznuni |

| Minister of Labour | Aramayis Erzinkian |

| Minister State Control | Ibrahim Haidarov |

Notes

- Russian: Закавказская демократическая Федеративная Республика (ЗДФР), Zakavkazskaya Demokraticheskaya Federativnaya Respublika (ZDFR).[3]

- Russia and the TDFR used the Julian calendar, which was 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar used by most of Europe at that time. Both switched to the Gregorian calendar in early 1918.[4] Both dates are given until February 1918, when Russia changed over, at which point only the Gregorian calendar is used.

- Prior to 1918, they were generally known as "Tatars". This term, employed by the Russians, referred to Turkish-speaking Muslims (Shia and Sunni) of Transcaucasia. Unlike the Armenians and Georgians, the Tatars did not have their own alphabet and used the Perso-Arabic script. After 1918 with the establishment of the Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, and "especially during the Soviet era", the Tatar group identified itself as "Azerbaijani".[5][6] Before 1918 the word "Azerbaijan" exclusively referred to the Iranian province of Azarbayjan.[7]

- Now the capital of Azerbaijan.

- Russian: Особый Закавказский Комитет; Osobyy Zakavkazskiy Komitet.[20]

- Saint Petersburg had been renamed Petrograd in 1914.[23]

- Russian: Совет; Sovet, meaning "Council".[24]

- Each deputy to the Constituent Assembly had represented 60,000 people, while this was lowered to 20,000 for the Seim, effectively tripling the number of representatives.[36]

- Russian: Совнарком; short for Совет народных комиссаров, Sovet narodnykh kommissarov.[36]

- Now known as Erzurum.[75]

References

- Brisku & Blauvelt 2020, p. 2

- Javakhishvili 2009, p. 159

- Uratadze 1956, p. 64

- Slye 2020, p. 119, note 1

- Bournoutian 2018, p. 35 (note 25).

- Tsutsiev 2014, p. 50.

- Bournoutian 2018, p. xiv.

- Saparov 2015, p. 20

- Saparov 2015, pp. 21–23

- Marshall 2010, p. 38

- King 2008, p. 146

- King 2008, p. 150

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 3

- King 2008, p. 154

- Marshall 2010, pp. 48–49

- Suny 2015, p. 228

- Kévorkian 2011, p. 721

- King 2008, pp. 157–158

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 32–33

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 75

- Hasanli 2016, p. 10

- Swietochowski 1985, pp. 84–85

- Reynolds 2011, p. 137

- Suny 1994, p. 186

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 35

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 54–56

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 57

- Swietochowski 1985, p. 106

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 58

- Mamoulia 2020, p. 23

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 84

- Swietochowski 1985, p. 108

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 85

- Engelstein 2018, p. 334

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 124

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 125

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 87

- Bakradze 2020, p. 60

- Swietochowski 1985, p. 110

- Hovannisian 1969, pp. 128–129

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 130

- Forestier-Peyrat 2016, p. 166

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 91

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 93

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 131

- Swietochowski 1985, p. 121

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 132

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 93–94

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 135

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 94–95

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 140

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 137

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 96

- Brisku 2020, p. 32

- Reynolds 2011, p. 203

- Hovannisian 1969, pp. 150–151

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 152

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 98–99

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 99

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 99–100

- Swietochowski 1985, p. 124

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 101

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 155

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 100

- Taglia 2020, p. 50

- Marshall 2010, p. 89

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 103

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 103–104

- Hovannisian 1969, pp. 159–160

- Hovannisian 1969, pp. 160–161

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 105

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 162

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 106

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 108

- de Waal 2015, p. 149

- Hovannisian 2012, pp. 292–294

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 163

- Hovannisian 1969, pp. 167–168

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 107

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 168

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 109

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 172

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 173

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 110

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 174

- Zolyan 2020, p. 17

- Hovannisian 2012, p. 299

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 176

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 113–114

- Hovannisian 1969, pp. 176–177

- Hovannisian 1969, pp. 177–179

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 115

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 183

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 184

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 181

- Kazemzadeh 1951, p. 120

- Hovannisian 1969, p. 188

- Suny 1994, pp. 191–192

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 123–124

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 125–127

- Kazemzadeh 1951, pp. 177–183, 215–216

- Brisku & Blauvelt 2020, p. 3

- Brisku & Blauvelt 2020, p. 1

- Jones 2005, p. 279

- King 2008, p. 187

- Brisku & Blauvelt 2020, p. 4

Bibliography

- Bakradze, Lasha (2020), "The German perspective on the Transcaucasian Federation and the influence of the Committee for Georgia's Independence", Caucasus Survey, 8 (1): 59–68, doi:10.1080/23761199.2020.1714877, S2CID 213498833

- Bournoutian, George (2018), Armenia and Imperial Decline: The Yerevan Province, 1900–1914, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-351-06260-2

- Brisku, Adrian (2020), "The Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (TDFR) as a "Georgian" responsibility", Caucasus Survey, 8 (1): 31–44, doi:10.1080/23761199.2020.1712902, S2CID 213610541

- Brisku, Adrian; Blauvelt, Timothy K. (2020), "Who wanted the TDFR? The making and the breaking of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic", Caucasus Survey, 8 (1): 1–8, doi:10.1080/23761199.2020.1712897

- de Waal, Thomas (2015), Great Catastrophe: Armenians and Turks in the Shadow of Genocide, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-935069-8

- Engelstein, Laura (2018), Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War 1914–1921, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-093150-6

- Forestier-Peyrat, Etienne (2016), "The Ottoman occupation of Batumi, 1918: A view from below" (PDF), Caucasus Survey, 4 (2): 165–182, doi:10.1080/23761199.2016.1173369, S2CID 163701318, archived (PDF) from the original on 19 July 2020, retrieved 6 August 2021

- Hasanli, Jamil (2016), Foreign Policy of the Republic of Azerbaijan: The Difficult Road to Western Integration, 1918–1920, New York City: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7656-4049-9

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (1969), Armenia on the Road to Independence, 1918, Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, LCCN 67-13649, OCLC 175119194

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (2012), "Armenia's Road to Independence", in Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.), The Armenian People From Ancient Times to Modern Times, Volume II: Foreign Dominion to Statehood: The Fifteenth Century to the Twentieth Century, Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: MacMillan, pp. 275–302, ISBN 978-0-333-61974-2

- Javakhishvili, Nikolai (2009), "History of the Unified Financial system in the Central Caucasus", The Caucasus & Globalization, 3 (1): 158–165

- Jones, Stephen F. (2005), Socialism in Georgian Colors: The European Road to Social Democracy 1883–1917, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-67-401902-7

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1951), The Struggle for Transcaucasia (1917–1921), New York City: Philosophical Library, ISBN 978-0-95-600040-8

- Kévorkian, Raymond (2011), The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History, Bloomsbury Publishing, ISBN 978-0-85771-930-0

- King, Charles (2008), The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-539239-5

- Mamoulia, Georges (2020), "Azerbaijan and the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic: historical reality and possibility", Caucasus Survey, 8 (1): 21–30, doi:10.1080/23761199.2020.1712901, S2CID 216497367

- Marshall, Alex (2010), The Caucasus Under Soviet Rule, New York City: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-41-541012-0

- Reynolds, Michael A. (2011), Shattering Empires: The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires 1908–1918, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-14916-7

- Saparov, Arsène (2015), From Conflict to Autonomy in the Caucasus: The Soviet Union and the making of Abkhazia, South Ossetia and Nagorno Karabakh, New York City: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-138-47615-8

- Slye, Sarah (2020), "Turning towards unity: A North Caucasian perspective on the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic", Caucasus Survey, 8 (1): 106–123, doi:10.1080/23761199.2020.1714882, S2CID 213140479

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994), The Making of the Georgian Nation (Second ed.), Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, ISBN 978-0-25-320915-3

- Suny, Ronald Grigor (2015), "They Can Live in the Desert but Nowhere Else": A History of the Armenian Genocide, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-14730-7

- Taglia, Stefano (2020), "Pragmatism and expediency: Ottoman calculations and the establishment of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic", Caucasus Survey, 8 (1): 45–58, doi:10.1080/23761199.2020.1712903, S2CID 213772764

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1985), Russian Azerbaijan, 1905–1920: The Shaping of National Identity in a Muslim Community, Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-52245-8

- Tsutsiev, Arthur (2014), "1886–1890: An Ethnolinguistic Map of the Caucasus", Atlas of the Ethno-Political History of the Caucasus, New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, pp. 48–51, ISBN 978-0-300-15308-8

- Uratadze, Grigorii Illarionovich (1956), Образование и консолидация Грузинской Демократической Республики [The Formation and Consolidation of the Georgian Democratic Republic] (in Russian), Moscow: Institut po izucheniyu istorii SSSR, OCLC 1040493575

- Zolyan, Mikayel (2020), "Between empire and independence: Armenia and the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic", Caucasus Survey, 8 (1): 9–20, doi:10.1080/23761199.2020.1712898, S2CID 216514705

Further reading

- Zürrer, Werner (1978), Kaukasien 1918–1921: Der Kampf der Großmächte um die Landbrücke zwischen Schwarzem und Kaspischem Meer [Caucasus 1918–1921: The Great Powers' Struggle for the Land Bridge between the Black and Caspian Seas] (in German), Düsseldorf: Droste Verlag GmbH, ISBN 3-7700-0515-5