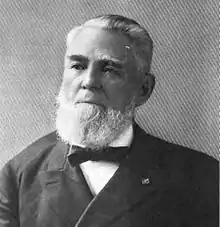

Allen D. Candler

Allen Daniel Candler (November 4, 1834 – October 26, 1910), was a Georgia state legislator, U.S. Representative and the 56th Governor of Georgia.

Allen Daniel Candler | |

|---|---|

| |

| 56th Governor of Georgia | |

| In office October 29, 1898 – October 25, 1902 | |

| Preceded by | William Y. Atkinson |

| Succeeded by | Joseph M. Terrell |

| 14th Secretary of State of Georgia | |

| In office 1894–1898 | |

| Preceded by | Philip Cook, Sr. |

| Succeeded by | William C. Clifton |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Georgia's 9th district | |

| In office March 4, 1883 – March 3, 1891 | |

| Preceded by | Emory Speer |

| Succeeded by | Thomas E. Winn |

| Member of the Georgia Senate | |

| In office 1878–1880 | |

| Member of the Georgia House of Representatives | |

| In office 1873–1878 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 4, 1834 Auraria, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | October 26, 1910 (aged 75) Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Eugenia Williams |

| Residence | Gainesville, Georgia |

| Alma mater | Mercer University |

| Occupation |

|

Early life

Candler was born the eldest of twelve children to Daniel Gill Candler and Nancy Caroline Matthews[1] in Auraria, Georgia, in Lumpkin County, a mountainous mining community. Candler attended country schools and then Mercer University in Macon, Georgia, graduating in 1859. Candler studied law briefly, and then taught school.

Civil War

In May 1862, Candler enlisted as a private in the Confederate 34th Georgia Volunteer Infantry, and was immediately elected a first lieutenant by the members of his company. Candler fought in some of the Civil War's most brutal battles: Vicksburg, Missionary Ridge, Resaca, Kennesaw Mountain, Atlanta, and Jonesboro. By war's end, he was serving as a colonel under General Joseph E. Johnston in the Army of Tennessee in North Carolina. He was wounded at Kennesaw and lost an eye in Jonesboro. At the end of the war, he quipped that he was more fortunate than many of his comrades -- "I counted myself quite wealthy [with] … one wife, and baby, one eye, and one silver dollar."[2]

Political life

After the war, Candler settled in Jonesboro, Georgia, then Gainesville, Georgia. He turned to farming, then politics; he was one of many conservative Democrats pushing to wrest control of the state back from the Reconstruction Republican state government, which was backed by the occupying Union Army. In 1872, he was elected Mayor of Gainesville. In 1873, he was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives, serving there until his election to the Georgia Senate in 1878, where he served just two years. During this time, Candler was also involved in manufacturing and was the president of a railroad.

In 1882, Candler was elected to the 48th Congress, serving in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1883 to 1891.[3] In 1886, he triggered a community conflict when he proposed a piece of legislation on behalf of some of his constituents. The law would set aside federal pension funds "for the relief of the First Georgia State Troops," the regiment organized by Union officer James G. Brown in 1864. Almost immediately after Congressman Candler offered his pension bill, north Georgia rebels burst into angry protest, calling the soldiers "first Georgia hogback Yankey fellers."[4]

In his third term as U.S. Representative, he was the chairman of the Committee on Education. Candler declined to run again in the 1890 election.

Candler served as Secretary of State of Georgia from 1894 to 1898 before resigning to pursue the Governorship. Campaigning as the "one-eyed ploughboy from Pigeon Roost" he won with 70% of the vote against Populist candidate J. R. Hogan. After a first two-year term, Candler was returned to office in 1900, defeating Populist candidate George W. Trayler.

Candler was known as a conservative governor. While he established pensions for Confederate widows, he otherwise cut back both taxes and government expenditures. Candler pushed for the establishment of a whites-only Democratic primary based on the legal notion that the Democratic Party was a private organization and therefore not subject to the Fifteenth Constitutional Amendment giving all Americans the right to vote, regardless of race. Since the Democratic Party had a monopoly on power in Southern states, the real selection of officeholders in Georgia occurred during the Democratic primary to select Democratic candidates for the fall general election. Democrats consistently won all of these offices from the end of Reconstruction in 1871 until the 1970s.

Candler's tenure as governor coincided with some of the most violent lynchings in Georgia's history.[5] Although he publicly denounced mob violence, at the same time he blamed the victims of these incidents on black criminality and the increasing annoyance among whites of blacks demanding equal treatment.[6] In an incident which culminated with the notorious lynching of Sam Hose in 1899,[7] he berated the "better class" of blacks for not aiding authorities in his apprehension. These views were prominently printed in the Atlanta newspapers alongside those of the editors which urged the mobs on.[8] Candler did ask the courts for speedier trials to head-off mob violence.

Death and legacy

After leaving the Governor's office, Candler served as the State's first compiler of records until his death in 1910 in Atlanta, Georgia. He was buried at Alta Vista cemetery in Gainesville.

Candler County, Georgia, was named in 1914 for Candler in appreciation for his passion and diligence in compiling and editing nearly thirty volumes of the State's historical records from the Colonial, Revolutionary and Confederate periods.

Notes

- Butts, p. 87

- Coleman, Kenneth (2010). American National Biography. London: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- "Candler campaign button". Campaign Materials Collection, Georgia Capitol Museum, University of Georgia Libraries. Digital Library of Georgia. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Sarris, Jonathan Dean (2006). A Separate Civil War : Communities In Conflict In The Mountain South. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. p. 176. ISBN 9780813925493.

- Brundage, pg. 202

- Arnold, Edwin T. (2009). 'What Virtue There Is in Fire' : Cultural Memory and the Lynching of Sam Hose. Athens: University of Georgia Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0820340647.

- Grem, Darren E. (2006). "Sam Jones, Sam Hose, and the Theology of Racial Violence". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 90 (1). Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- Davis, p. 115

References

- Butts, Sarah Harriett, Mothers of Some Distinguished Georgians, J.J. Little & Co., 1902

- Brundage, William Fitzhugh, Lynching in the New South: Georgia and Virginia, 1880-1930, University of Illinois Press, 1993, ISBN 0-252-06345-7

- Davis, Leroy, A Clashing of the Soul: John Hope and the Dilemma of African American Leadership and Black Higher Education in the Early Twentieth Century, University of Georgia Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8203-1987-2

External links

- United States Congress. "Allen D. Candler (id: C000109)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved on 2009-03-01

- New Georgia Encyclopedia entry Archived 2007-02-25 at the Wayback Machine

- Governor Allen Daniel Candler: Confederate Colonel

- Two Georgia Governors