Amanda Stepto

Amanda Felicitas Stepto (born 31 July 1970) is a Canadian actress who is best known for her role as Christine "Spike" Nelson in the Degrassi television franchise, which she portrayed from 1987 to 1992, and again as an adult from 2001 to 2008. Having no previous acting experience, Stepto rose to prominence as Spike in the critically and commercially successful CBC series Degrassi Junior High (1987–89) and its follow-up Degrassi High (1989–91).

Amanda Stepto | |

|---|---|

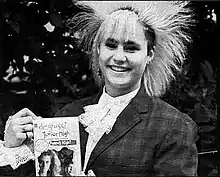

Stepto promoting Degrassi Junior High in the United Kingdom in 1988 | |

| Born | Amanda Felicitas Stepto July 31, 1970 |

| Education | Etobicoke School of the Arts |

| Alma mater | University of Toronto |

| Occupation(s) | Actress, DJ |

| Years active | 1986–2010 |

| Known for | Playing Christine "Spike" Nelson in the Degrassi franchise |

| Television | Degrassi Junior High, Degrassi High, Degrassi: The Next Generation |

Spike's controversial teenage pregnancy storyline, as well as her spiked hairstyle, gave Stepto significant media attention in Canada. Degrassi Junior High was largely truncated and later dropped by the BBC in large part due to episodes about Spike's pregnancy. As part of the Playing With Time Repertory Company, Stepto was made a Goodwill Ambassador of UNICEF Ontario. In the early 1990s, Stepto was a spokesperson for Planned Parenthood and was sponsored by the organization for a controversial 1993 tour of Albertan high schools.

Having left acting in the 1990s due to typecasting and lost of interest, Stepto returned to reprise the role of Spike as an adult in the first seven seasons of Degrassi: The Next Generation (2001–08). Degrassi remains her only major acting role. She was praised for her performance and was nominated for a Young Artist Award (as part of an ensemble) and a Gemini Award.

Early life: 1970-1986

Amanda Felicitas Stepto[1] was born on 31 July 1970 in Montreal, Quebec,[2] the child of a young local woman and an "American jazz musician just passing through".[3] Her birth mother put her up for adoption at three months old.[4][3] She spent her early years residing in Meadowvale, Mississauga.[5] In a podcast interview, Stepto recalled her first exposure to punk rock as being a concert by English new wave band The Police in Oakville, Ontario in August 1981, where she was struck by the styles of punks in the audience.[6] Stepto developed her trademark spiked hair when she was fourteen,[7] citing Colin Abrahall, vocalist of the UK82 band GBH, as her chief stylistic inspiration.[8] In 1987, she cited her favorite bands and artists as being Duran Duran, Billy Idol, Sex Pistols, Platinum Blonde, and The Cult.[9] She attended the Etobicoke School of the Arts for three years, where she majored in dance and minored in drama,[10] and later a school in Mississauga while on starring on television.[11]

Degrassi: 1987-1992

At Etobicoke School of the Arts, Stepto learnt of an open audition for a television series named Degrassi Junior High from her drama teacher.[11][note 1] She was the only student to act on it.[11] She did not have a resume or professional headshots,[11][12] and was required to send in a photo of herself to the production company. An argument ensued between Stepto and her parents, who felt her punk hairstyle wasn't suitable for television.[13] She insisted she keep her hair for the picture, telling her parents, "If they don't like me, fuck them!".[13] She was subsequently accepted.[12]

When her character became pregnant, fans mistook her for being pregnant in real life, and would often send the actress toys.[14] She was also often asked for advice from parents and teenage mothers on sex and pregnancy as if she was a counselor.[14][15] In the United Kingdom, where Degrassi Junior High experienced its highest viewership, the BBC refused to air "It's Late" along with several other episodes,[16] shortly before Stepto was expected to promote the series in London.[17]

Stepto was critical of the BBC's decision when speaking to the British press. Speaking to the Daily Mirror on 13 May 1988, Stepto called the ban "kinda silly", and elaborated: "The issues we've been dealing with in the episodes they wouldn't show happen everywhere and people are going to find out about them sooner or later."[18] She also explained that the show intended to educate its viewers on the subject and did not encourage it at all.[19] Stepto later recalled that the press in the United Kingdom tried to make her "talk shit" about the BBC.[20]

Stepto was among the cast of Degrassi that were named UNICEF Goodwill Ambassadors by the Ontario branch of UNICEF Canada in 1989.[21][22] Along with cast member Pat Mastroianni, Stepto visited the Headquarters of the United Nations in New York City, and met with other ambassadors.[21] She served as the narrator for the UNICEF video The Degrassi Kids Rap On Rights.[23]

In 1991, shortly after Degrassi High ended its run on television, Stepto was one of six actors from the show who participated in Degrassi Talks, a documentary series in which cast members interviewed teenagers and young adults across Canada about various topics. She was the host of an episode that discussed teenage pregnancy, safe sex, and abortion. In the episode, she interviewed a woman who gave her baby up for adoption, an experience which had a profound impact on Stepto.[24]

Post-Degrassi: 1992-1995

Following the end of Degrassi, Stepto indicated to the Calgary Herald that she was interested in further pursuing her acting career, and stated that she was particularly interested in playing destructive, "psychotic" characters.[25] However, she later recalled that she experienced typecasting as a result of her previous role.[7][26][27] She claimed she would also sabotage her own auditions to avoid getting roles in series she disliked,[27] including the YTV musical drama series Catwalk, which she derided as a "cheesy low-budget show",[15] and felt this may have contributed to her difficulty in continuing her acting career.[27] During 1991 and 1992, Stepto starred in the play Flesh and Blood, written by Colin Thomas, about several young adults dealing with AIDS;[28][29] the play won a Floyd S. Chalmers Canadian Play Award for playwriting in 1991.[28][30]

In 1992, she was appointed a spokesperson for Planned Parenthood in Alberta.[31] Stepto visited Calgary as a representative of the organization in September 1992.[32] Starting from May 1993, Stepto undertook a 37-stop tour of schools across the province to promote a campaign by Planned Parenthood; a viewing of the Degrassi Talks episode she hosted was optional.[33] On 28 April 1993, the Calgary Herald reported that three Albertan schools had refused Stepto's presentation, though two of the schools later said that they were not aware of the program.[34] In addition, Stepto also appeared in television, radio, and print advertisements promoting the "Just Talk About It" campaign during September 1992.[35]

Later career: 1995-present

In 1995, she starred in a supporting role in the Su Rynard short film Big Deal So What, playing the friend and colleague of the protagonist.[36] She eventually left the acting business to concentrate on school.[15] At the 2022 Toronto Comicon, Stepto explained that she had extreme difficulty pursuing a career in acting following the show; the roles she was offered were usually similar to Spike, and she was directly rejected for being too well-known as Spike.[37] Additionally, she said that producers would constantly tell her that she was "too short", "too fat", or "cheeks are too full",[37] and eventually she was "tired of all that bullshit"[37] and left the acting business to pursue other endeavors.[37]

She returned in 2001 to reprise the role of Spike in Degrassi: The Next Generation, which begins primarily centering around Spike's daughter Emma. She appears in a recurring role for the show's first nine seasons, appearing less frequently in later seasons and departing along with the original cast following the telemovie Degrassi Takes Manhattan in 2010. She would make only a couple of minor television appearances outside of Degrassi: in 2000, she had a bit role in the pilot episode of the American medical drama Strong Medicine, where she played a lady in the waiting room. In 2007, she appeared as a guest star on the science fiction series ReGenesis, playing a scientist who dies in a car explosion caused by a dangerous biochemical. Stepto has said that she still is "drawn back into the acting world every once in a while".[27]

Legacy

Public image

Stepto's "outrageously-coiffed"[38] hair, which she stated was the result of "lots of Final Net",[39] contributed to the media attention she received during the late 1980s. Edmonton Journal staff writer Bob Remington quipped that her hairstyle resembled "a science experiment in electromagnetism".[40] The hairstyle came to be seen as a trademark of both the actress and the character she portrayed on television.[41][42] Stepto has recalled receiving unwanted attention and harassment as a result of the hairstyle.[39] Speaking to The Grid in 2012, she said that this attention caused her confusion upon her rise to fame: "I realized I couldn’t [continue to] tell people to fuck off and stop staring at me—they were staring at me because I was on the show."[43]

Stepto has also recalled being forced to leave public places on multiple occasions because of her hair, once recalling an incident where she was told to leave the Toronto Eaton Centre for "lolling around", despite carrying hundreds of dollars worth of items including a dress for an upcoming awards ceremony.[44] She also recalled getting a "strike" from her ballet teacher as the hair "didn't go with the pink getup".[11] According to Stepto, the harassment inspired a storyline in Degrassi Junior High where Spike is mocked by a diner owner during a job interview.[45] In later interviews, she recalled occasionally getting angry letters from other girls in the punk rock scene threatening to physically attack her because their boyfriends were attracted to her.[46][47]

Degrassi

Amanda Stepto was acclaimed for her "honest"[48] portrayal of Spike, and the character has been cited as a "fan favourite",[49] a "trailblazer",[50] and important to the franchise's continuity.[48] Ian Warden of The Canberra Times described Spike as a "lynchpin" of the series.[51] Stepto was frequently recognized and mobbed by fans.[52]

Personal life

Stepto graduated from the University of Toronto with a bachelor's degree in history and political science.[53] She briefly resided in Japan to teach English during the late 1990s.[15][53] She has stated she is an advocate for animal rights,[39][25] and a vegetarian.[54] She cites Morrissey, as well as the Smiths album Meat Is Murder, as a form of validation for her vegetarianism, noting: "I reveled in finding an artist that spoke to me in that way."[55] During the 1990s, she was the manager of the clothing store Shakti, located in the Kensington Market,[15][53] and operated a jewelry booth at Lollapalooza with co-star Cathy Keenan.[15] In 2009, she began performing as a DJ in Toronto under the name "DJ Demanda" with former co-star Stacie Mistysyn, who went under the name "Mistylicious".[1][56]

Award nominations

Stepto has been nominated twice for her role as Christine "Spike" Nelson in Degrassi. In 1990, along with her co-stars, she was nominated for the Young Artist Award for Outstanding Young Ensemble Cast for Degrassi Junior High.[58] In 1992, she was nominated for the Gemini Award for Best Performance by an Actress in a Continuing Leading Dramatic Role for Degrassi High.[59][60][61] She appeared as a celebrity presenter at the ceremony.[62]

Filmography

Film

| Year | Work | Role | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | Big Deal So What | Ruth | [36] |

Television

| Year | Work | Role | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987–1989 | Degrassi Junior High | Christine "Spike" Nelson | [63] |

| 1989–1991 | Degrassi High | [64] | |

| 1992 | School's Out | [65] | |

| Degrassi Talks | Herself | [65] | |

| 2001–2010 | Degrassi: The Next Generation | Christine "Spike" Nelson | [65] |

Notes

- The preface to Degrassi Talks: Sex was written by writer Catherine Dunphy. Stepto gave her own account in a 1998 interview with Degrassi fan site owner Natalie Earl, where she says she discovered the audition via an announcement posted in Etobicoke School Of The Arts' drama department. "Amanda Stepto Interview for MARK". 3 February 2007. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

References

- "Amanda Stepto". De Grassi Tour. Archived from the original on 25 April 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - Lucas, Ralph (30 July 2016). "Amanda Stepto". Northernstars.ca. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- Boardwalk 1992, pp. 15

- Kennedy, Janice (16 December 1988). "Spike speaks out for teen mothers; Star of CBC's Degrassi Junior High has become a symbol". Montreal Gazette. Archived from the original on 13 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2021..

- Boardwalk 1992, pp. 13

- Damian Abraham (7 April 2016). "Episode 74 - Amanda Stepto (from TV's Degrassi!!!!)". Turned Out A Punk! (Podcast). Audioboom. Event occurs at 8:52-10:47. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Mike Park (10 January 2019). "Episode 011 "It's Late" W/ Amanda Stepto Interview". I'm In Love With A Girl Named Spike (Podcast). Libsyn. Event occurs at 1:10:32-1:10:47. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Damian Abraham (7 April 2016). "Episode 74 - Amanda Stepto (from TV's Degrassi!!!!)". Turned Out A Punk! (Podcast). Audioboom. Event occurs at 19:30-19:43. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Mackie, Joan (22 March 1987). "'Average teen' actress and rock fan has bedroom plastered with pictures". The Toronto Star.

- Boardwalk 1992, pp. 13–14

- Boardwalk 1992, pp. 14

- Damian Abraham (7 April 2016). "Episode 74 - Amanda Stepto (from TV's Degrassi!!!!)". Turned Out A Punk! (Podcast). Audioboom. Event occurs at 18:15-19:28. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Bilton, Chris; Liss, Sarah (26 April 2012). "Degrassi Junior High: the oral history (Page 1)". The Grid. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- Boardwalk 1992, pp. 9

- "Amanda Stepto (Christine "Spike" Nelson) Interview by Natalie Earl". 3 February 2007. Archived from the original on 3 February 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- "China picks up Degrassi Junior High". The Toronto Star. Los Angeles Times. 11 May 1988. ISSN 0319-0781.

- "Pregnancy offends British taste". Winnipeg Free Press. 26 May 1988. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- Murray, Neil (13 May 1988). "Beeb ban is a puzzle to punk Amanda". Daily Mirror. p. 9. Retrieved 23 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- Richmond, Annie (19 May 1988). "Scoop meets the banned Degrassi girl...". SCOOP. p. 6.

- Mike Park (10 January 2019). ""It's Late" W/ Amanda Stepto Interview". I'm In Love With A Girl Named Spike (Podcast). Libsyn. Event occurs at 1:43:38-1:43:42. Retrieved 26 April 2021.

- Playing with Time, Inc (1 June 1989). "All in a good cause". Classmates Newsletter. Retrieved 3 May 2021.

{{cite news}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Ellis 2005, pp. 140

- "Media celebrities increase public awareness". The Toronto Star. 30 October 1990.

- Boardwalk 1992, pp. 7

- Mayes, Alison (24 February 1992). "Degrassi Talks". Calgary Herald. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 11 May 2021.

- Leung, Wency (17 May 2010). "Don't I know you...? What happens when Star Wars Kid grows up?". The Globe and Mail.

- Mike Park (10 January 2019). "Episode 011 "It's Late" W/ Amanda Stepto Interview". I'm In Love With A Girl Named Spike (Podcast). Libsyn. Event occurs at 54:21-54:56. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Lacey, Liam (5 May 1992). "Drama speaks to teen-agers about AIDS". The Toronto Star.

- Cushman, Robert (9 April 1991). "Morality not simple in moral Theatre Direct play". The Globe and Mail.

- "Canadian playwrights honored". Edmonton Journal. 25 February 1992.

- McConnell, Rick (9 June 1993). "Time to spike apathy". Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Tait, Mark (22 September 1992). "TV teen offers straight talk on sex". Calgary Herald. p. 17. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- "Spike speaks, but not everyone is clapping". Alberta Report. United Western Communications. 24 May 1993.

- Dawson, Chris (28 April 1993). "Schools turn down program". Calgary Herald. p. 21. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- Wright, Lisa (22 September 1992). "Talk about sex to your teens, agency urges". The Toronto Star.

- "Big Deal So What – Su Rynard". Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- Canada's Premier DJ, DJ Immortal (20 March 2022). Toronto Comic Con Q&A With Degrassi Junior High Cast (Caitlin, Joey & Spike) 03/19/2022 (Video). Event occurs at 15:55-16:30.

- Mullen, Patrick (14 February 2018). "Degrassi". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Ellis 2005, pp. 46

- Remington, Bob (9 December 1988). "Degrassi stories now out in books". Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 6 June 2021.

- Swanson, Judy (22 January 1989). "Spike hits nail on head". The Province. p. 81. Retrieved 18 May 2021.

And her punk hairstyle is the trademark of her character Spike on the CBC show Degrassi Junior High.

- "'Spike' appeals to teens". Winnipeg Free Press. 15 December 1988. p. 48. Archived from the original on 13 April 2021. Retrieved 13 April 2021.

Stepto is actually 18 and hasn't been pregnant. But the trademark haircut is real.

- Bilton, Chris; Liss, Sarah (26 April 2012). "Degrassi Junior High: the oral history (Page 2)". The Grid. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- Damian Abraham (7 April 2016). "Episode 74 - Amanda Stepto (from TV's Degrassi!!!!)". Turned Out A Punk! (Podcast). Audioboom. Event occurs at 26:44-27:35. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Ellis 2005, pp. 46

- "Degrassi Junior High: the oral history". 28 April 2012. Archived from the original on 28 April 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- Damian Abraham (8 April 2016). "Episode 74 - Amanda Stepto (from TV's Degrassi!!!!)". Turned Out A Punk (Podcast). Audioboom. Retrieved 30 March 2021.

- Mazumdar 2020, pp. 108

- Riches, Hester (8 December 1988). "Degrassi series takes on new edge: Acting also better, cast member feels". The Vancouver Sun. p. F3. ISSN 0832-1299. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- Giese, Rachel (October 2008). "Why TV turns us on". Chatelaine.

- "PM's marzipan sweeter than Ms Wendt's eclair". The Canberra Times. Vol. 65, no. 20, 491. Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 20 May 1991. p. 28. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- Boardwalk 1992, pp. 8

- Ellis 2005, pp. 47

- Damian Abraham (7 April 2016). "Episode 74 - Amanda Stepto (from TV's Degrassi!!!!)". Turned Out A Punk! (Podcast). Audioboom. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Damian Abraham (7 April 2016). "Episode 74 - Amanda Stepto (from TV's Degrassi!!!!)". Turned Out A Punk! (Podcast). Audioboom. Event occurs at 22:28-23:08. Archived from the original on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- Ongsansoy, Hans (20 June 2009). "Spike - from 'Degrassi' to DJ booth". Nanaimo Daily News. p. 24. Archived from the original on 5 June 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2021.

- Slotek, Jim (15 March 2017). "Pat Mastroianni on the 'Degrassi' reunion, working with Drake and dropping the F-bomb". torontosun. Archived from the original on 15 March 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- "11th Annual Awards". 9 April 2014. Archived from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- "Canada's Awards Database". 3 September 2009. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 28 March 2021.

- Anderson, Bill (23 January 1992). "Road to Avonlea, E.N.G. leading contenders for Canadian TV awards". The Ottawa Citizen. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Remington, Bob (8 March 1992). "E.N.G. newsies battle Avonlea kids". Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on 11 June 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- Quill, Greg (27 February 1992). "Gemini decides on presenters". The Toronto Star.

- "Degrassi Fan Pages". Degrassi Fan Pages. 4 June 2004. Archived from the original on 4 June 2004. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- "Degrassi Fan Pages". Degrassi Fan Pages. 7 April 2004. Archived from the original on 7 April 2004. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- "Degrassi Fan Pages". Degrassi Fan Pages. 4 June 2004. Archived from the original on 14 June 2004. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

Sources

- Degrassi Talks: Sex. Toronto: Boardwalk Books. 1992. pp. 8–15. ISBN 1-895681-01-4. OCLC 25370148.

- Ellis, Kathryn (2005). The official 411 Degrassi generations. Fenn Pub. Co. pp. 46–47. ISBN 1-55168-278-8. OCLC 59136593.

- Women and popular culture in Canada. Laine Zisman Newman. Toronto. 2020. pp. 104–108. ISBN 978-0-88961-615-8. OCLC 1140640717.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link)