Family in the United States

In the United States, the traditional family structure is considered a family support system involving two married individuals providing care and stability for their biological offspring. However, this two-parent, heterosexual, nuclear family has become less prevalent, and nontraditional family forms have become more common.[2] The family is created at birth and establishes ties across generations.[3] Those generations, the extended family of aunts and uncles, grandparents, and cousins, can hold significant emotional and economic roles for the nuclear family.

Over time, the structure has had to adapt to very influential changes, including divorce and more single-parent families, teenage pregnancy and unwed mothers, same-sex marriage, and increased interest in adoption. Social movements such as the feminist movement and the stay-at-home father have contributed to the creation of alternative family forms, generating new versions of the American family.

At a glance

Nuclear family

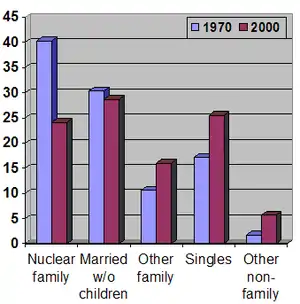

The nuclear family has been considered the "traditional" family structure since the Soviet Union scare in the cold war of the 1950s. The nuclear family consists of a mother, father, and the children. The two-parent nuclear family has become less prevalent, and pre-American and European family forms have become more common.[2] Beginning in the 1970s in the United States, the structure of the "traditional" nuclear American family began to change. It was the women in the households that began to make this change. They decided to begin careers outside of the home and not live according to the male figures in their lives.[4]

These include same-sex relationships, single-parent households, adopting individuals, and extended family systems living together. The nuclear family is also having fewer children than in the past.[5] The percentage of nuclear-family households is approximately half what it was at its peak in the middle of the 20th century.[6] The percentage of married-couple households with children under 18, but without other family members (such as grandparents), has declined to 23.5% of all households in 2000 from 25.6% in 1990, and from 45% in 1960. In November 2016, the Current Population Survey of the United States Census Bureau reported that 69 percent of children under the age of 18 lived with two parents, which was a decline from 88 percent in 1960.[7]

Single parent

A single parent (also termed lone parent or sole parent) is a parent who cares for one or more children without the assistance of the other biological parent. Historically, single-parent families often resulted from death of a spouse, for instance in childbirth. This term is can be broken down into two types: sole parent and co-parent. A sole parent is managing all of the responsibilities of child-rearing on their own without financial or emotional assistance. A sole parent can be a product of abandonment or death of the other parent or can be a single adoption or artificial insemination. A co-parent is someone who still gets some type of assistance with the child/children. Single-parent homes are increasing as married couples divorce, or as unmarried couples have children. Although widely believed to be detrimental to the mental and physical well-being of a child, this type of household is tolerated.[8]

The percentage of single-parent households has doubled in the last three decades, but that percentage tripled between 1900 and 1950.[9] The sense of marriage as a "permanent" institution has been weakened, allowing individuals to consider leaving marriages more readily than they may have in the past.[10] Increasingly, single-parent families are due to out of wedlock births, especially those due to unintended pregnancy. From 1960 to 2016, the percentage of U.S. children under 18 living with one parent increased from 9 percent (8 percent with mothers, 1 percent with fathers) to 27 percent (23 percent with mothers, 4 percent with fathers).[7]

Stepfamilies

Stepfamilies are becoming more familiar in America. Divorce rates are rising and the remarriage rate is rising as well, therefore, bringing two families together making stepfamilies. Statistics show that there are 1,300 new stepfamilies forming every day. Over half of American families are remarried, that is 75% of marriages ending in divorce, remarry.[11]

Extended family

The extended family consists of grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. In some circumstances, the extended family comes to live either with or in place of a member of the nuclear family. An example includes elderly parents who move in with their adult children due to old age. This places large demands on the caregivers.[12]

Historically, among certain Asian and Native American cultures, the family structure consisted of a grandmother and her children, especially daughters, who raised their own children together and shared child care responsibilities. Uncles, brothers, and other male relatives sometimes helped out. Romantic relationships between men and women were formed and dissolved with little impact on the children who remained in the mother's extended family.

History

Roles and relationships

Married partners

A married couple was defined as a "husband and wife enumerated as members of the same household" by the U.S. Census Bureau,[13] but they will be categorizing same-sex couples as married couples if they are married. Same-sex couples who were married were previously recognized by the Census Bureau as unmarried partners.[14] Same-sex marriage is legally permitted across the country since June 26, 2015, when the Supreme Court issued its decision in Obergefell v. Hodges. Polygamy is illegal throughout the U.S.[15]

Although marriages of first cousins are illegal in many states, they are legal in many other states, the District of Columbia and some territories. Some states have some restrictions or exceptions for cousin marriages and/or recognize such marriages performed out-of-state. Since the 1940s, the United States marriage rate has decreased, whereas rates of divorce have increased.[16]

Unwed partners

Living as unwed partners is also known as cohabitation. The number of heterosexual unmarried couples in the United States has increased tenfold, from about 400,000 in 1960 to more than five million in 2005.[17] This number would increase by at least another 594,000 if same-sex partners were included.[17] Of all unmarried couples, about 1 in 9 (11.1% of all unmarried-partner households) are homosexual.[17]

The cohabitation lifestyle is becoming more popular in today's generation.[18] It is more convenient for couples not to get married because it can be cheaper and simpler. As divorce rates rise in society, the desire to get married is less attractive for couples uncertain of their long-term plans.[17]

Parents

Parents can be either the biological mother or biological father, or the legal guardian for adopted children. Traditionally, mothers were responsible for raising the kids while the father was out providing financially for the family. The age group for parents ranges from teenage parents to grandparents who have decided to raise their grandchildren, with teenage pregnancies fluctuating based on race and culture.[19] Older parents are financially established and generally have fewer problems raising children compared to their teenage counterparts.[20] In 2013, the highest teenage birth rate was in Alabama, and the lowest in Wyoming.[21][22]

Housewives

A housewife or "homemaker" is a married woman who is not employed outside the home to earn income, but stays at home and takes care of the home and children. This includes doing common chores such as cooking, washing, cleaning, etc. The roles of women working within the house have changed drastically as more women start to pursue careers. The amount of time women spend doing housework declined from 27 hours per week in 1965, to less than 16 hours in 1995, but it is still substantially more housework than their male partners.[23]

"Breadwinners"

A breadwinner is the main financial provider in the family. Historically husbands in opposite-sex couples have been breadwinners; that trend is changing as wives start to take advantage of the women's movement to gain financial independence for themselves. According to The New York Times, "In 2001, wives earned more than their spouses in almost a third of married households where the wife worked."[24]

Stay-at-home dads

Stay-at-home dads or "househusbands" are fathers that do not participate in the workforce and stay at home to raise their children—the male equivalent to housewives. Stay-at-home dads are not as popular in American society.[25] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, "There are an estimated 105,000 'stay-at-home' dads. These are married fathers with children under fifteen years of age who are not in the workforce primarily so they can care for family members, while their wives work for a living outside the home. Stay-at-home dads care for 189,000 children."[26]

Children

Only child families

An only child (single child) is a child without siblings. Some evidence suggests that only children may perform better in school and in their careers than children with siblings.[23]

Childfree and childlessness

Childfree couples choose to not have children. These include young couples, who plan to have children later, as well as those who do not plan to have any children. Involuntary childlessness may be caused by infertility, medical problems, death of a child, or other factors.

Adopted children

Adopted children are children that were given up at birth, abandoned or were unable to be cared for by their biological parents. They may have been put into foster care before finding their permanent residence. It is particularly hard for adopted children to get adopted from foster care: 50,000 children were adopted in 2001.[27] The average age of these children was 7, which shows that fewer older children were adopted.[27]

Modern family models

Same-sex marriage, adoption, and child rearing

Same-sex parents are gay, lesbian, or bisexual couples that choose to raise children. Nationally, 66% of female same-sex couples and 44% of male same-sex couples live with children under eighteen years old.[25] In the 2000 United States Census, there were 594,000 households that claimed to be headed by same-sex couples, with 72% of those having children.[28] In July 2004, the American Psychological Association concluded that "Overall results of research suggests that the development, adjustment, and well-being of children with lesbian and gay and bisexual parents do not differ markedly from that of children with heterosexual parents."[29]

Transgender Parenting

Many studies show that transgender peoples are equally committed to and invested in their families in comparison to other family structures. However, there are reasons for familial destruction when a trans person "comes out" as so. This is most likely due to fear. There is a lot of fear surrounding the transgender community, and the negative stigma can lead to familial alienation.[30] When looking at, more specifically, the trans parent-child relationship, we see that those who identify as transgender claim that their relationships to their children were overall good in nature. The parent-child relational reports among trans parents were primarily positive.[31] While these statistics are positive, transgender parenting does have some barriers. Some include biological relatedness, physical limitations, or lack of legal protections. Specifically, with biological relatedness, trans people felt as though it was nearly impossible to attain. Hormonal treatments, surgeries, and the inability to use "traditional" methods all posed a challenge.[32] All this to say, transgender familial relationships were mostly good overall, yet there were a few blockades. It is also important to recognize that trans familial relationships and experiences in general are different from gay, lesbian, or bisexual experiences.[30]

Single-parent households

Single-parent homes in America are increasingly common. With more children being born to unmarried couples and to couples whose marriages subsequently dissolve, more children live with just one parent. The proportion of children living with a never-married parent has grown, from 4% in 1960 to 42% in 2001.[33] Of all single-parent families, 83% are mother-child families.[33]

Adoption requirements

The adoption requirements and policies for adopting children have made it harder for foster families and potential adoptive families to adopt. Before a family can adopt, they must go through the state, county, and agency criteria. Adoption agencies' criteria express the importance of age of the adoptive parents, as well as the agency's desire for married couples over single adopters.[34] Adoptive parents also have to deal with criteria that are given by the birth parents of the adoptive child. The different criteria for adopting children makes it harder for couples to adopt children in need,[34] but the strict requirements can help protect the foster children from unqualified couples.[34]

Currently 1,500,000 (2% of all U.S. children) are adopted. There are different types of adoption; embryo adoption when a couple is having trouble conceiving a child and instead choose to adopt an embryo that was created using another couple's sperm and egg conjoined outside the womb, this often occurs with leftover embryos from another couple's successful IVF cycle. international adoption where couples adopt children that come from foreign countries, and private adoption which is the most common form of adoption. In a private adoption, families can adopt children via licensed agencies or by directly contacting the child's biological parents.

Male/female role pressures

The traditional "father" and "mother" roles of the nuclear family have become blurred over time. Because of the women's movement's push for women to engage in traditionally masculine pursuits in society, as women choose to sacrifice their child-bearing years to establish their careers, and as fathers feel increasing pressure, as well as desire, to be involved with tending to children, the traditional roles of fathers as the "breadwinners" and mothers as the "caretakers" have come into question.[35]

African-American family structure

The family structure of African-Americans has long been a matter of national public policy interest.[36] The 1965 report by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, known as The Moynihan Report, examined the link between black poverty and family structure.[36] It hypothesized that the destruction of the Black nuclear family structure would hinder further progress toward economic and political equality.[36]

When Moynihan wrote in 1965 on the coming destruction of the Black family, the out-of-wedlock birthrate was 25% amongst Blacks.[37] In 1991, 68% of Black children were born outside of marriage.[38] In 2011, 72% of Black babies were born to unwed mothers.[39][40]

Recent trends

Post-materialist and postmodern values have become research topics related to the family.[41] According to Judith Stacy in 1990, "We are living, I believe, through a transitional and contested period of family history, a period 'after' the modern family order."[42] As of 2019, there are more than 110 million single people in the United States. More than 50% of the American adult population is single compared to 22% in 1950. Jeremy Greenwood, Professor of economics at the University of Pennsylvania has explored how technological progress has affected the family. In particular, he discusses how technological advance has led to more married women working, a decline in fertility, an increase in the number of single households, social change, longer lifespans, and a rise in the fraction of life spent in retirement.[43] Sociologist Elyakim Kislev lists some of the major drivers for the decline in the family institution: women's growing independence, risk aversion in an age of divorce, demanding careers, rising levels of education, individualism, secularization, popular media, growing transnational mobility, and urbanization processes.[44]

Television portrayals

The television industry initially helped create a stereotype of the American nuclear family. During the era of the baby boomers, families became a popular social topic, especially on television.[45] Family shows such as Roseanne, All in the Family, Leave It to Beaver, The Cosby Show, Married... with Children, The Jeffersons, Good Times, and Everybody Loves Raymond have portrayed different social classes of families growing up in America. Those "perfect" nuclear families have changed as the years passed and have become more inclusive, showing single-parent and divorced families, as well as older singles.[8] Television shows that show single-parent families include Half & Half, One on One, Murphy Brown, and Gilmore Girls.

While it did not become a common occurrence the iconic image of the American family was started in the early-1930s. It was not until WWII that families generally had the economic income in which to successfully propagate this lifestyle.[46]

See also

- Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States

- Divorce in the United States

- Polyamory in the United States

- Work–family balance in the United States

International:

References

-

- Grove, Robert D.; Hetzel, Alice M. (1968). Vital Statistics Rates in the United States 1940-1960 (PDF) (Report). Public Health Service Publication. Vol. 1677. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, U.S. Public Health Service, National Center for Health Statistics. p. 185.

- Ventura, Stephanie J.; Bachrach, Christine A. (October 18, 2000). Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States, 1940-99 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 48. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. pp. 28–31.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Park, Melissa M. (February 12, 2002). Births: Final Data for 2000 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 50. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Park, Melissa M.; Sutton, Paul D. (December 18, 2002). Births: Final Data for 2001 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 51. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 47.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Munson, Martha L. (December 17, 2003). Births: Final Data for 2002 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 52. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 57.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Munson, Martha L. (September 8, 2005). Births: Final Data for 2003 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 54. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 52.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Kirmeyer, Sharon (September 29, 2006). Births: Final Data for 2004 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 55. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 57.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Munson, Martha L. (December 5, 2007). Births: Final Data for 2005 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 56. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 57.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Menacker, Fay; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Mathews, T.J. (January 7, 2009). Births: Final Data for 2006 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 57. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 54.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Mathews, T.J.; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Osterman, Michelle J.K. (August 9, 2010). Births: Final Data for 2007 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 58. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Sutton, Paul D.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Mathews, T.J.; Osterman, Michelle J.K. (December 8, 2010). Births: Final Data for 2008 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 59. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Kirmeyer, Sharon; Mathews, T.J.; Wilson, Elizabeth C. (November 3, 2011). Births: Final Data for 2009 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 60. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 46.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Wilson, Elizabeth C.; Mathews, T.J. (August 28, 2012). Births: Final Data for 2010 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 61. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 45.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Ventura, Stephanie J.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Mathews, T.J. (June 28, 2013). Births: Final Data for 2011 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 62. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 43.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Curtin, Sally C. (December 30, 2013). Births: Final Data for 2012 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 62. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 41.

- Martin, Joyce A.; Hamilton, Brady E.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Curtin, Sally C.; Mathews, T.J. (January 15, 2015). Births: Final Data for 2013 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 64. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. p. 40.

- Hamilton, Brady E.; Martin, Joyce A.; Osterman, Michelle J.K.; Curtin, Sally C.; Mathews, T.J. (December 23, 2015). Births: Final Data for 2014 (PDF) (Report). National Vital Statistics Reports. Vol. 64. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. pp. 7 & 41.

- Edwards, H.N. (1987). Changing family structure and youthful well-being. Journal of Family Issues 8, 355–372

- Beutler, Burr, Bahr, and Herrin (1989) p. 806; cited by Fine, Mark A. in Families in the United States: Their Current Status and Future Prospects Copyright 1992

- Stewart Foley, Michael (2013). Front Porch Politics The Forgotten Heyday of American Activism in the 1970s and 1980s. Hill and Wang. ISBN 978-0-8090-4797-0.

- "For First Time since the cold war, Nuclear Families Drop Below 25% of Households". Uscsumter.edu. May 15, 2001. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- Brooks, Story by David. "The Nuclear Family Was a Mistake". The Atlantic. ISSN 1072-7825. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- "The Majority of Children Live With Two Parents, Census Bureau Reports". United States Census Bureau. November 17, 2016. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- Benokraitis, N: Marriages & families, page 7. sixth edition, 2007

- Benokraitis, N: Marriages & families, page 18. sixth edition, 2007

- Glenn, N.D. (1987). Continuity versus change, sanguineness versus concern: Views of the American family in the late 1980s. Journal of Family Issues 8, 348–354

- Stewart, S.D. (2007). Brave New Stepfamilies. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Brubaker, T.H. (1990). Continuity and change in later life families: Grandparenthood, couple relationships and family caregiving. Gerentology Review 3, 24–40

- Teachman, Tedrow, Crowder. The Changing Demography of America's Families Journal of Marriage and the Family, Vol. 62 (Nov 2000) p. 1234

- "Census to change the way it counts gay married couples". Washington Post.

- Barbara Bradley Hagerty (May 27, 2008). "Some Muslims in U.S. Quietly Engage in Polygamy". National Public Radio: All Things Considered. Retrieved July 23, 2009.

- Teachman, Tedrow, Crowder. The Changing Demography of America's Families. Journal of Marriage and the Family, Vol. 62 (Nov 2000) p. 1235

- Benokraitis, N: Marriages & families, page 271. sixth edition, 2007

- Benokraitis, N: Marriages & families, page 275. sixth edition, 2007

- Benokraitis, N: Marriages & families, page 326. sixth edition, 2007

- Benokraitis, N: Marriages & families, pp. 328–329. sixth edition, 2007

- "Births: Final Data for 2013, tables 2, 3" (PDF). U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- "Trends in Teen Pregnancy and Childbearing". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- Benokraitis, N: Marriages & families, page 367. sixth edition, 2007

- Gardner, Ralph (November 10, 2003). "Alpha Women, Beta Men – When wives are the family breadwinners". Nymag.com. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- Benokraitis, N: Marriages & families, page 328. sixth edition, 2007

- "US Census Press Releases". Census.gov. Archived from the original on November 18, 2003. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- "Child's Finalization Age (Grouped)". Acf.hhs.gov. Archived from the original on August 30, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- U.S. Census Bureau, Married-Couple and Unmarried-Partner Households: 2000 (February 2003)

- Meezan, William and Rauch, Jonathan. Gay Marriage, Same-sex Parenting, and America's Children. The Future of Children Vol. 15 No. 2 Marriage and Child Wellbeing (Autumn 2005) p. 102

- Hafford‐Letchfield, Trish; Cocker, Christine; Rutter, Deborah; Tinarwo, Moreblessing; McCormack, Keira; Manning, Rebecca (April 14, 2019). "What do we know about transgender parenting?: Findings from a systematic review". Health & Social Care in the Community. 27 (5): 1111–1125. doi:10.1111/hsc.12759. ISSN 0966-0410. PMID 30983067. S2CID 115199269.

- thisisloyal.com, Loyal |. "Transgender Parenting". Williams Institute. Retrieved May 3, 2023.

- Tornello, Samantha L.; Bos, Henny (April 1, 2017). "Parenting Intentions Among Transgender Individuals". LGBT Health. 4 (2): 115–120. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0153. hdl:11245.1/42a0adb3-9668-4bcb-b3ae-c9fe184320fa. ISSN 2325-8292. PMID 28212056. S2CID 7938150.

- Benokraitis, N: Marriages & families, page 20–21. sixth edition, 2007

- "Review of Qualification Requirements for Prospective Adoptive Parents – Agencies, Agency, Alcohol, A". Adopting.adoption.com. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- Fine, Mark A. Families in the United States: Their Current Status and Future Prospects. Family Relations vol. 41 (Oct 1992) p. 431

- "U.S. Department of Labor -- History -- The Negro Family - The Case for National Action". www.dol.gov. Archived from the original on January 20, 2017. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- Daniel P. Moynihan, The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, Washington, D.C., Office of Policy Planning and Research, U.S. Department of Labor, 1965.

- National Review, April 4, 1994, p. 24.

- "Blacks struggle with 72 percent unwed mothers rate", Jesse Washington, NBC News, July 11, 2010

- "For Blacks, the Pyrrhic Victory of the Obama Era", Jason L. Riley, The Wall Street Journal, November 4, 2012

- Kislev, Elyakim. (September 1, 2017). "Happiness, Post-materialist Values, and the Unmarried". Journal of Happiness Studies. 19 (8): 2243–2265. doi:10.1007/s10902-017-9921-7. ISSN 1573-7780. S2CID 148812711.

- Marvin B. Sussman; Suzanne K. Steinmetz; Gary W. Peterson (2013). Handbook of Marriage and the Family. Springer. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-4757-5367-7.

- Greenwood, Jeremy (2019). Evolving Households: The Imprint of Technology on Life. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-03923-9.

- Kislev, Elyakim (2019). Happy Singlehood: The Rising Acceptance and Celebration of Solo Living. University of California Press.

- Benokraitis, N: Marriages & families, page 7–8. sixth edition, 2007

- Etuk, Lena. "How Family Structure has Changed". Oregon State University. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

Further reading

- Aulette, Judith R. ed. Changing American Families (3rd ed. 2009)

- Benokraitis, Nijole. Marriages and Families: Changes, Choices, and Constraints (9th ed 2018)

- Bertocchi, Graziella, and Arcangelo Dimico. "Bitter sugar: Slavery and the Black family." (2020). online

- Buchanan, Ann. "Brothers and sisters: Themes in myths, legends and histories from Europe and the New World." in Brothers and Sisters. (Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, 2021) pp. 69–86.

- Ciabattari, Teresa. Sociology of Families: Change, Continuity, and Diversity (2021)

- Campbell, D'Ann. Women at war with America: Private lives in a patriotic era (Harvard UP, 1984).

- Chambers, Deborah and Pablo Gracia. A Sociology of Family Life: Change and Diversity in Intimate Relations (2022)

- Coontz, Stephanie. "'Leave It to Beaver' and 'Ozzie and Harriet': American Families in the 1950s." in Undoing Place? (Routledge, 2020) pp. 22–32.

- Degler, Carl. At Odds: Women and the Family in America from the Revolution to the Present (1980).

- Elder Jr, Glen H. "History and the family: The discovery of complexity." Journal of Marriage and the Family (1981): 489-519. online

- Gutman, Herbert G. The Black family in slavery and freedom, 1750-1925 (Vintage, 1977).

- Hareven, Tamara K. "The history of the family and the complexity of social change." American Historical Review 96.1 (1991): 95-124.

- Hareven, Tamara K. "The home and the family in historical perspective." Social research (1991): 253-285.

- Hareven, Tamara K., and Maris A. Vinovskis, eds. Family and population in 19th century America (Princeton University Press, 2015).

- Hareven, Tamara K. "Family time and industrial time: family and work in a planned corporation town, 1900–1924." Journal of Urban History 1.3 (1975): 365-389.

- Holmes, Amy E., and Maris A. Vinovskis. "Widowhood in Nineteenth-Century America." in The Changing American Family: Sociological And Demographic Perspectives (2019).

- Jones, Jacqueline. Labor of love, labor of sorrow: Black women, work, and the family, from slavery to the present (Basic Books, 2009).

- Mintz, Steven; Susan Kellogg (1989). Domestic Revolutions: A Social History of American Family Life. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-02-921291-2.

- Mintz, Steven (1983). A Prison of Expectation: The Family in Victorian Culture. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5388-0.

- Mintz, Steven. "Children, Families and the State: American Family Law in Historical Perspective." Denver University Law Review 69 (1992): 635-661. online

- Mintz, Steven. "Regulating the American family." Journal of Family History14.4 (1989): 387-408.

- Peterson, Carla L. Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City (Yale University Press, 2011).

- Sanders, Jeffrey C. Razing kids: youth, environment, and the postwar American West (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

- Schneider, Norbert F., and Michaela Kreyenfeld. Research Handbook on the Sociology of the Family (2021)

- Smith, Daniel Scott. " 'Early' Fertility Decline in America: a Problem in Family History." Journal of Family History 12.1-3 (1987): 73-84.

- South, Scott J., and Stewart Tolnay. The changing American family: Sociological and demographic perspectives (Routledge, 2019).

- Vinovskis, Maris A. "Family and schooling in colonial and nineteenth-century America." Journal of Family History 12.1-3 (1987): 19-37. online

- Vinovskis, Maris A. "Historical perspectives on the development of the family and parent-child interactions." in Parenting across the life span (Routledge, 2017) pp. 295–312.

- Wright, Bailey, and D. Nicole Farris. "Marriage Practices of North America." International Handbook on the Demography of Marriage and the Family (Springer, Cham, 2020) pp. 51–63.

.svg.png.webp)