Federalist Era

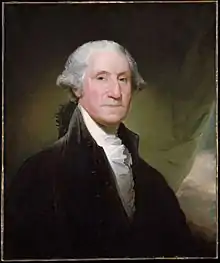

The Federalist Era in American history ran from 1788 to 1800, a time when the Federalist Party and its predecessors were dominant in American politics. During this period, Federalists generally controlled Congress and enjoyed the support of President George Washington and President John Adams. The era saw the creation of a new, stronger federal government under the United States Constitution, a deepening of support for nationalism, and diminished fears of tyranny by a central government. The era began with the ratification of the United States Constitution and ended with the Democratic-Republican Party's victory in the 1800 elections.

| Federalist Era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1788–1800 | |||

Washington's first inauguration | |||

| Location | United States | ||

| Leader(s) | George Washington John Adams Alexander Hamilton John Jay | ||

| Key events | Whiskey Rebellion Quasi-War Jay Treaty Northwest Indian War Bill of Rights Alien and Sedition Acts Bank Bill of 1791 Coinage Act of 1792 | ||

Chronology

| |||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of the United States |

|---|

|

|

During the 1780s, the "Confederation Period", the new nation functioned under the Articles of Confederation, which provided for a loose confederation of states. At the 1787 Philadelphia Convention, delegates from most of the states wrote a new constitution that created a more powerful federal government. After the convention, this constitution was submitted to the states for ratification. Those who advocated ratification became known as Federalists, while those opposed to ratification became known as anti-Federalists. After the Federalists won the ratification debate in all but two states, the new constitution took effect and new elections were held for Congress and the presidency. The first elections returned large Federalist majorities in both houses and elected George Washington, who had taken part in the Philadelphia Convention, as president. The Washington administration and the 1st United States Congress established numerous precedents and much of the structure of the new government. Congress shaped the federal judiciary with the Judiciary Act of 1789 while Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton's economic policies fostered a strong central government. The first Congress also passed the United States Bill of Rights to constitutionally limit the powers of the federal government. During the Federalist Era, American foreign policy was dominated by concerns regarding Britain, France, and Spain. Washington and Adams sought to avoid war with each of these countries while ensuring continued trade and settlement of the American frontier.[1]

Hamilton's policies divided the United States along factional lines, creating voter-based political parties for the first time. Hamilton mobilized urban elites who favored his financial and economic policies. His opponents coalesced around Thomas Jefferson and James Madison. Jefferson feared that Hamilton's policies would lead to an aristocratic, and potentially monarchical, society that clashed with his vision of a republic built on yeomen farmers. This economic policy debate was further roiled by the French Revolutionary Wars, as Jeffersonians tended to sympathize with France and Hamiltonians with Britain. The Jay Treaty established peaceful commercial relations with Britain, but outraged the Jeffersonians and damaged relations with France. Hamilton's followers organized into the Federalist Party while the Jeffersonians organized into the Democratic-Republican Party. Though many who had sought ratification of the Constitution joined the Federalist Party, some advocates of the Constitution, led by Madison, became members of the Democratic-Republicans. The Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party contested the 1796 presidential election, with the Federalist Adams emerging triumphant. From 1798 to 1800, the United States engaged in the Quasi-War with France, and many Americans rallied to Adams. In the wake of these foreign policy tensions, the Federalists imposed the Alien and Sedition Acts to crack down on dissidents and make it more difficult for immigrants to become citizens. Historian Carol Berkin argues that the Federalists successfully strengthened the national government, without arousing fears of tyranny.[2]

The Federalists embraced a quasi-aristocratic, elitist vision that was unpopular with most Americans outside of the middle class. Jefferson's egalitarian vision appealed to farmers and middle-class urbanites alike and the party embraced campaign tactics that mobilized all classes of society. Although the Federalists retained strength in New England and other parts of the Northeast, the Democratic-Republicans dominated the South and West and became the more successful party in much of the Northeast. In the 1800 elections, Jefferson defeated Adams for the presidency and the Democratic-Republicans took control of Congress. Jefferson accurately referred to the election as the "Revolution of 1800", as Jeffersonian democracy came to dominate the country in the succeeding decades. The Federalists experienced a brief resurgence during the War of 1812, but collapsed after the war. Despite the Federalist Party's demise, many of the institutions and structures established by the party would endure, and Hamilton's economic policies would influence generations of American political leaders.[3]

Federalist Era begins

The United States Constitution was written at the 1787 Philadelphia Convention and ratified by the states in 1788, taking effect in 1789. During the 1780s, the United States had operated under the Articles of Confederation, which was essentially a treaty of thirteen sovereign states.[4] Domestic and foreign policy challenges convinced many in the United States of the need for a new constitution that provided for a stronger national government. The supporters of ratification of the Constitution were called Federalists while the opponents were called Anti-Federalists. The immediate problem faced by the Federalists was not simply one of acceptance of the Constitution but the more fundamental concern of legitimacy for the government of the new republic.[5] With this challenge in mind, the new national government needed to act with the idea that every act was being carried out for the first time and would therefore have great significance and be viewed along the lines of the symbolic as well as practical implications. The first elections to the new United States Congress returned heavy Federalist majorities.[6] George Washington, who had presided over the Philadelphia Convention, was unanimously chosen as the first President of the United States by the Electoral College.

The Anti-Federalist movement opposed the draft Constitution primarily because it lacked a bill of rights. They also objected to the new powerful central government, the loss of prestige for the states, and saw the Constitution as a potential threat to personal liberties.[7] During the ratification process, the Anti-Federalists presented a significant opposition in all but three states. The major stumbling block for the Anti-Federalists, according to Elkins and McKitrick's The Age of Federalism, was that the supporters of the Constitution had been more deeply committed, had cared more, and had outmaneuvered the less energetic opposition. The Anti-Federalists did temporarily prevent ratification in two states, North Carolina and Rhode Island, but both states would ratify the Constitution after 1788.

Establishing a new government

The Constitution had established the basic layout of the federal government, but much of the structure of the government was established during the Federalist Era. The Constitution empowers the president to appoint the heads of the federal executive departments with the advice and consent of the Senate. President Washington and the Senate established a precedent whereby the president alone would make executive and judicial nominations, but these nominees would not hold their positions in a permanent capacity until they won Senate confirmation. President Washington organized his principal officers into the Cabinet of the United States, which served as a major advisory body to the president. The heads of the Department of War, the Department of State, and the Department of the Treasury each served in the Cabinet. After the passage of the Judiciary Act of 1789, the Attorney General also served in the Cabinet as the president's chief legal adviser.

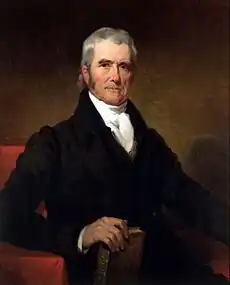

In addition to creating the office of the Attorney General, the Judiciary Act of 1789 also established the federal judiciary. Article Three of the United States Constitution had created the judicial branch of the federal government and invested powers in it, but had left it to Congress and the president to determine the number of Supreme Court Justices, establish courts below the Supreme Court, and appoint individuals to serve in the judicial branch. Written primarily by Senator Oliver Ellsworth, the Judiciary Act of 1789 established a six-member Supreme Court and created circuit courts and district courts in thirteen judicial districts. The ensuing Crimes Act of 1790 defined several statutory federal crimes and the punishment for those crimes, but the state court systems handled the vast majority of civil and criminal cases. Washington nominated the first group of federal judges in September 1789 and appointed several judges in the following years. John Jay served as the first Chief Justice of the United States and he would be succeeded in turn by John Rutledge, Oliver Ellsworth, and John Marshall.

Proponents of the Constitution had won the ratification debate in several states in part by promising that they would introduce a bill of rights to the Constitution via the amendment process.[8] Congressman James Madison, who had been a prominent advocate of the Constitution's ratification, introduced a series of amendments that would become known as the United States Bill of Rights. Congress passed twelve articles of amendment, and ten were ratified before the end of 1791. The Bill of Rights codified the protection of individual liberties against the federal government, with those liberties including freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and the right to a jury trial in all criminal cases.

At the start of the Federalist Era, New York City was the nation's capital, but the Constitution had provided for the establishment of a permanent national capital under federal authority. Article One of the Constitution permits the establishment of a "District (not exceeding ten miles square) as may, by cession of particular states, and the acceptance of Congress, become the seat of the government of the United States".[9] In what is now known as the Compromise of 1790, Madison, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Jefferson came to an agreement that the federal government would pay each state's remaining Revolutionary War debts in exchange for establishing the new national capital in the Southern United States.[10] In July 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which approved the creation of a national capital on the Potomac River. The exact location was to be selected by President George Washington. Maryland and Virginia donated land to the federal government that collectively formed a square measuring 10 miles (16 km) on each side.[11] The Residence Act also established Philadelphia as the federal capital until the government moved to the federal district. Congress adjourned its last meeting in Philadelphia on May 15, 1800, and the city officially ceased to be the nation's seat of government as of June 1800.[12] President John Adams moved into the White House later that year.

Economic policy

Raising revenue

Among the many contentious issues facing the First Congress during its inaugural session was the issue of how to raise revenue for the federal government. There were both domestic and foreign Revolutionary War-related debts, as well as a trade imbalance with Great Britain that was crippling American industries and draining the nation of its currency. The new national government needed revenue and decided to depend upon a tariff or tax on imports with the Tariff of 1789.[13]

Various other plans were considered to address the debt issues during the first session of Congress, but none were able to generate widespread support. In September 1789, with no resolution in sight and the close of that session drawing near, Congress directed Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton to prepare a report on credit.[14] In his Report on the Public Credit, Hamilton called for the federal assumption of state debt and the mass issuance of federal bonds. Hamilton believed that these measures would restore the ailing economy, ensure a stable and adequate money stock, and make it easier for the federal government to borrow during emergencies such as wars.[15]

Despite the additional import duties imposed by the Tariff of 1790, a substantial federal deficit remained – chiefly due to the federal assumption of stated debts.[16] By December 1790, Hamilton believed import duties, which were the government's primary source of revenue, had been raised as high as was feasible.[17] He therefore promoted passage of an excise tax on domestically distilled spirits. This was to be the first tax levied by the national government on a domestic product.[18] Although taxes were politically unpopular, Hamilton believed the whiskey excise was a luxury tax that would be the least objectionable tax the government could levy.[19][20] The tax also had the support of some social reformers, who hoped a "sin tax" would raise public awareness about the harmful effects of alcohol.[21] The Distilled Spirits Duties Act, commonly known as the "Whiskey Act" went into effect in June 1791.[22][23]

Assumption of state debts

Hamilton also proposed the federal assumption of state debts, many of which were heavy burdens on the states. Congressional delegations from the Southern states, which had lower or no debts, and whose citizens would effectively pay a portion of the debt of other states if the federal government assumed it, were disinclined to accept the proposal. The southern states felt this to be extremely unfair, which caused a division between the southern states and the northern states. Additionally, many in Congress argued that the plan was beyond the constitutional power of the new government. James Madison led the effort to block the provision and prevent the plan from gaining approval.[24] Jefferson approved payment of the domestic and foreign debt at par, but not the assumption of state debts.[25] A compromise had to be reached. The final compromise had to do with the location of a permanent national capital, which was undecided until then. It was made so that the capital would be on the banks of the Potomac River in the South in return for the Southern votes on assumption. After Hamilton and Jefferson reached the Compromise of 1790, Hamilton's assumption plan was adopted as the Funding Act of 1790.

Other Hamiltonian proposals

Later in 1790, Hamilton issued another set of recommendations in his Second Report on Public Credit. The report called for the establishment of a national bank and an excise tax on distilled spirits. Hamilton's proposed national bank would provide credit to fledgling industries, serve as a depository for government funds, and oversee one nationwide currency. In response to Hamilton's proposal, Congress passed the Bank Bill of 1791, establishing the First Bank of the United States.[26] The following year, it passed the Coinage Act of 1792, establishing the United States Mint, and the United States dollar, and regulating the coinage of the United States.[27]

In December 1791, Hamilton published the Report on Manufactures, which recommended numerous policies designed to protect U.S. merchants and industries in order to increase national wealth, induce artisans to immigrate, cause machinery to be invented, and employ women and children.[28] Hamilton called for federally-funded infrastructure projects, the establishment of state-owned munitions factories and subsidies for privately owned factories, and the imposition of a protective tariff.[29] Though Congress had adopted much of Hamilton's earlier proposals, his manufacturing proposals fell flat, even in the more-industrialized North, as merchant-shipowners had a stake in free trade.[28] These opponents also raised questions regarding the constitutionality of Hamilton's proposals. Jefferson and others feared that Hamilton's expansive interpretation of the Taxing and Spending Clause would grant Congress the power to legislate on any subject. Opponents of Hamilton won several seats in the 1792 Congressional elections, and Hamilton was unable to win Congressional approval of his ambitious economic proposals after 1792.[29] Federalists would not pass further major economic until after John Adams took office as president in 1797.

Quasi-War taxation

To pay for the military buildup of the Quasi-War, Adams and his Federalist allies enacted the Direct Tax of 1798. Direct taxation by the federal government was widely unpopular, and the government's revenue under Washington had mostly come from excise taxes and tariffs. Though Washington had maintained a balanced budget with the help of a growing economy, increased military expenditures threatened to cause major budget deficits, and Hamilton, Wolcott, and Adams developed a taxation plan to meet the need for increased government revenue. The Direct Tax of 1798 instituted a progressive land value tax of up to 1% of the value of a property. Taxpayers in eastern Pennsylvania resisted federal tax collectors, and in March 1799 the bloodless Fries's Rebellion broke out. Led by Revolutionary War veteran John Fries, rural German-speaking farmers protested what they saw as a threat to their republican liberties and to their churches.[30] The tax revolt raised the specter of class warfare, and Hamilton led the army into the area to put down the revolt. The subsequent trial of Fries gained wide national attention, and Adams pardoned Fries and two others after they were sentenced to be executed for treason. The rebellion, the deployment of the army, and the results of the trials alienated many in Pennsylvania and other states from the Federalist Party, damaging Adams's re-election hopes.[31]

Rise of political parties

| House | Senate | |

|---|---|---|

| 1788 | 43% | 31% |

| 1790 | 43% | 45% |

| 1792 | 51% | 47% |

| 1794 | 56% | 34% |

| 1796 | 46% | 31% |

| 1800 | 43% | 31% |

| 1802 | 63% | 53% |

| 1804 | 73% | 74% |

Foundation

Realizing the need for broad political support for his programs, Hamilton formed connections with like-minded nationalists throughout the country. He used his network of treasury agents to link together friends of the government, especially merchants and bankers, in the new nation's major cities. What had begun as a faction in Congress supportive of Hamilton's economic policies emerged into a national faction and then, finally, as the Federalist Party.[33] The Federalist Party supported Hamilton's vision of a strong centralized government, and agreed with his proposals for a national bank and government subsidies for industries. In foreign affairs, they supported neutrality in the war between France and Great Britain.[34]

The Democratic-Republican Party was founded in 1792 by Jefferson and James Madison. The party was created in order to oppose the policies of Hamilton and his Federalist Party. It also opposed the Jay Treaty of 1794 with Britain and supported good relations with France. The Democratic-Republicans espoused a strict constructionist interpretation of the Constitution, and denounced many of Hamilton's proposals, especially the national bank, as unconstitutional. The party promoted states' rights and the primacy of the yeoman farmer over bankers, industrialists, merchants, and other monied interests. The party supported states' rights as a measure against the tyrannical nature of a large centralized government that they feared the Federal government could have easily become.[35]

Nationwide parties

The state networks of both parties began to operate in 1794 or 1795 and patronage became a major factor in party-building. The winner-takes-all election system opened a wide gap between winners, who got all the patronage, and losers, who got none. Hamilton had many lucrative Treasury jobs to dispense—there were 1,700 of them by 1801.[36] Jefferson had one part-time job in the State Department, which he gave to journalist Philip Freneau to attack the Federalists. In New York, however, George Clinton won the election for governor and used the vast state patronage fund to help the Republican cause.

The Federalist Party became popular with businessmen and New Englanders; Republicans were mostly farmers who opposed a strong central government. Cities were usually Federalist strongholds; frontier regions were heavily Republican. These are generalizations; there are special cases: the Presbyterians of upland North Carolina, who had immigrated just before the Revolution, and often been Tories, became Federalists.[37] The Congregationalists of New England and the Episcopalians in the larger cities supported the Federalists, while other minority denominations tended toward the Republican camp. Catholics in Maryland were generally Federalists.[38]

The Federalists derided democracy as equivalent to mob rule and believed that government should be guided by the political and economic elite.[39] Many Federalists saw themselves less as a political party than as a collection of the elite who were the rightful leaders of the country.[40] Federalists thought that American society would become more hierarchical and less egalitarian in the decades following the ratification of the Constitution.[41] As the 1790s progressed, the Federalists increasingly lost touch with the beliefs and ideologies of average Americans, who tended to prefer the ideology espoused by the Democratic-Republicans.[41] Their strength as a party was largely based on Washington's popularity and good judgment, which deflected many public attacks, and his death in 1799 damaged the party.[42]

The Democratic-Republicans embraced the republican ideology that had emerged during the American Revolution.[41] Jefferson sought to build a republic centering around the yeoman farmer, and he despised the influence of Northern business interests.[43] As the 1790s progressed, Democratic-Republicans increasingly embraced political participation by all free white men.[39] In contrast to the Federalists, the Democratic-Republicans argued that each individual in society, regardless of their standing, had the right hold and express their own opinion. While individual opinions could be poorly informed or outright wrong, Democratic-Republicans believed that these individuals views would aggregate into a public opinion that could be trusted as representative of the broad American interest.[44]

Western frontier

Whiskey Rebellion

The federal excise tax of 1791 aroused major opposition on the American frontier, particularly in Western Pennsylvania. Corn, the chief crop on the frontier, was too bulky to ship over the mountains to market, unless it was first distilled into whiskey. After the imposition of the excise tax, the backwoodsmen complained the tax fell on them rather than on the consumers. They felt that this tax on liquor was very similar to the acts passed by the British, and thought this to be against the rights presented to them by the Constitution. Cash poor, they were outraged that they had been singled for taxation, especially since they felt this money went to Eastern moneyed interests and the federal revenue officers who began to swarm the hills looking for illegal stills.[45][46]

Insurgents in Western Pennsylvania shut the courts and hounded federal officials, but Jeffersonian leader Albert Gallatin mobilized the western moderates, and thus forestalled a serious outbreak of violence. Washington, seeing the need to assert federal supremacy, called out 13,000 state militia, and marched toward Washington, Pennsylvania, to suppress what was called the Whiskey Rebellion. The rebellion evaporated in late 1794 as the army approached. The rebels dispersed before any major fighting occurred. The point that Washington was trying to make here was that the government had the power and will to enforce the law. If citizens wanted to change the law, it was better to do it through the ballot boxes and courts, as opposed to through violence. Federalists were relieved that the new government proved capable of overcoming rebellion, while Republicans, with Gallatin their new hero, argued there never was a real rebellion and the whole episode was manipulated in order to accustom Americans to a standing army.[47]

The Northwest Indian War

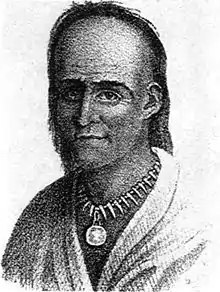

|

|

Chief Little Turtle (mihšihkinaahkwa) |

Major General Anthony Wayne |

Britain had ceded land extending as far west as the Mississippi River in the Treaty of Paris of 1783. Following adoption of the Land Ordinance of 1785, American settlers began freely moving west across the Allegheny Mountains and into the Native American-occupied lands beyond. As they did, they encountered unyielding and often violent resistance from a confederation of tribes. After taking office, Washington directed the Army to enforce American sovereignty over the region. Brigadier General Josiah Harmar launched a major offensive against the Shawnee and Miami Indians in the Harmar Campaign, but was repulsed by the Native Americans.[48] Determined to avenge the defeat, the president ordered Major General Arthur St. Clair to mount a more vigorous effort. St. Clair's poorly trained force was almost annihilated by a force of 2,000 warriors led by Little Turtle, Blue Jacket, and Tecumseh.[49]

British officials in Upper Canada were delighted and encouraged by the success of the Indians, whom they had been supporting and arming for years. In 1792 Lieutenant Governor John Graves Simcoe proposed that the entire territory be erected into an Indian barrier state. The British government did not pursue this idea, but it refused to relinquish control of its forts on the U.S. frontier.[50][51]

Outraged by news of the defeat, Washington urged Congress to raise an army capable of conducting a successful offense against the Indian confederacy, which it did in March 1792 – establishing additional Army regiments (the Legion of the United States), adding three-year enlistments, and increasing military pay.[52] Congress passed also two Militia Acts empowering the president to call out the militias of the several states and requiring every free able-bodied white male citizen of between the ages of 18 and 45 to enroll in the state militia.[53] Washington ordered General Anthony Wayne to lead a new expedition against Western Confederacy. Wayne's soldiers encountered Indian confederacy forces led by Blue Jacket, in what has become known as the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Wayne's cavalry outflanked and routed Blue Jacket's warriors, who fled towards Fort Miami. Unwilling to start a war with the United States, the British commander of Fort Miami refused to assist the Indians. Wayne's soldiers spent several days destroying the nearby Indian villages and crops, before withdrawing.[54]

Native American resistance to Wayne's army quickly collapsed following the battle,[54] and delegates from the various confederation tribes gathered for a peace conference at Fort Greene Ville in June 1795. The conference re in the Treaty of Greenville between the assembled tribes and the United States.[50] Under its terms, the tribes ceded most of what is now Ohio for American settlement and recognized the United States as the ruling power in the region. The Treaty of Greenville, along with the recently signed Jay Treaty, solidified U.S. sovereignty over the Northwest Territory.[55]

Foreign affairs

Neutrality

International affairs, especially the French Revolution and the subsequent war between Britain and France, decisively shaped American politics in 1793–1800, and threatened to entangle the nation in potentially devastating wars.[56] Britain joined the War of the First Coalition after the 1793 execution of King Louis XVI of France. Louis XVI had been decisive in helping America achieve independence, and his death horrified many in the United States. Federalists warned that American republicans threatened to replicate the excesses of the French Revolution, and successfully mobilized most conservatives and many clergymen. The Democratic-Republicans, many of whom were strong Francophiles, largely supported the French Revolution. Some of these leaders began backing away from support of the Revolution during the Reign of Terror, but they continued to favor the French over the British.[57] The Republicans denounced Hamilton, Adams, and even Washington as friends of Britain, as secret monarchists, and as enemies of the republican values.[58][59]

In 1793, French ambassador Edmond Charles Genêt (known as Citizen Genêt) arrived in the United States. He systematically mobilized pro-French sentiment and encouraged Americans to support France's war against Britain and Spain. Genêt funded local Democratic-Republican Societies that attacked Federalists.[60] He hoped for a favorable new treaty and for repayment of the debts owed to France. Acting aggressively, Genêt outfitted privateers that sailed with American crews under a French flag and attacked British shipping. He tried to organize expeditions of Americans to invade Spanish Louisiana and Spanish Florida. When Secretary of State Jefferson told Genêt he was pushing American friendship past the limit, Genêt threatened to go over the government's head and rouse public opinion on behalf of France. Even Jefferson agreed this was blatant foreign interference in domestic politics. Genêt's extremism seriously embarrassed the Jeffersonians and cooled popular support for promoting the French Revolution and getting involved in its wars. Recalled to Paris for execution, Genêt kept his head and instead went to New York, where he became a citizen and married the daughter of Governor Clinton.[61] Jefferson left office, ending the coalition cabinet and allowing the Federalists to dominate.[62]

Jay Treaty

.jpg.webp)

Washington sent John Jay to Britain to resolve numerous difficulties, some leftover from the Treaty of Paris and some having arisen during the French Revolutionary Wars. These issues included boundary disputes, debts owed in each direction, and the continued presence of British forts in the Northwest Territory. In addition, America hoped to open markets in the British Caribbean and end disputes stemming from the naval war between Britain and France. As a neutral party, the United States argued, it had the right to carry goods anywhere it wanted, but the British seized American ships that traded with the French.[63] In the Jay Treaty, the British agreed to evacuate the western forts, open their West Indies ports to American ships, allow small vessels to trade with the French West Indies, and set up a commission that would adjudicate American claims against Britain for seized ships, and British claims against Americans for debts incurred before 1775.[64]

The Democratic-Republicans wanted to pressure Britain to the brink of war, assuming that the United States could defeat a weak Britain.[65] They denounced the Jay Treaty as an insult to American prestige, a repudiation of the French alliance of 1777, and a severe shock to Southern planters who owed those old debts, and who were never to collect for the lost slaves the British captured. Republicans protested against the treaty and organized their supporters. The Federalists realized they had to mobilize their popular vote, so they mobilized their newspapers, held rallies, counted votes, and especially relied on the prestige of President Washington. The contest over the Jay Treaty marked the first flowering of grassroots political activism in America, directed and coordinated by two national parties. Politics was no longer the domain of politicians; every voter was called on to participate. The new strategy of appealing directly to the public worked for the Federalists; public opinion shifted to support the Jay Treaty.[66] The Federalists controlled the Senate and they ratified it by exactly the necessary ⅔ vote, 20–10, in 1795.[67]

Spanish territories

During the 1780s, Spain had sought to slow the expansion of the U.S. and lure American settlers into secession from the United States.[68] Washington feared that Spain (as well as Britain) might successfully incite insurrection against the U.S. if he failed to open trade on the Mississippi, and he sent envoy Thomas Pinckney to Spain with that goal in mind. Fearing that the United States and Great Britain might unite to take Spanish territory, Spain decided to seek accommodation with the United States.[69] The two parties signed the Pinckney's Treaty (officially called The Treaty of San Lorenzo) in 1795, establishing intentions of friendship between the United States and Spain.[70][71] It marked the end of Spanish hostility, and the end of Spanish expansion. The two nations agreed not to incite native tribes to warfare. The western boundary of the U.S. was established along the Mississippi River from the northern boundary of the United States to the 31st degree north latitude, while the southern boundary of the United States was established on the 31st parallel north.[72] In 1798 the U.S. organized the once-disputed territory into the Mississippi Territory in 1798.[73]

Most importantly, Pinckney's Treaty conceded unrestricted access of the entire Mississippi River to Americans, opening much of the Ohio River Valley for settlement and trade. Agricultural produce could now flow on flatboats down the Ohio and Cumberland Rivers to the Mississippi River and on to New Orleans and Europe. Spain and the United States also agreed to protect the vessels of the other party anywhere within their jurisdictions and to not detain or embargo the other's citizens or vessels. The treaty also guaranteed navigation of the entire length of the river for both the United States and Spain.[73] The treaty represented a major victory for Washington's western policy and placated many of the critics of the Jay Treaty.[74]

XYZ Affair and Quasi-War with France

President Adams hoped to maintain friendly relations with France, and after taking office he sent a delegation to Paris asking for compensation for the French attacks on American shipping. Adams appointed a three-member commission to represent the United States to negotiate with France. When the envoys arrived in October 1797, they were kept waiting for several days, and then granted only a 15-minute meeting with French Foreign Minister Talleyrand. After this, the diplomats were met by three of Talleyrand's agents. Each refused to conduct diplomatic negotiations unless the United States paid enormous bribes, one to Talleyrand personally, and another to the Republic of France. The Americans refused to negotiate on such terms. Marshall and Pinckney returned home, while Gerry remained.[75]

In an April 1798 speech to Congress, Adams publicly revealed Talleyrand's machinations, sparking public outrage at the French. Jeffersonian Republicans were skeptical of the administration's account of what became known as the XYZ affair, and many opposed Adams's efforts to defend against the French. They feared that war with France would lead to an alliance with England, which in turn could promote monarchism at home.[76]

Following the affair, the United States and France fought a series of naval engagements in an undeclared war known as the Quasi-War. In light of the threat of invasion from the more powerful French forces, Adams asked Congress to authorize the creation of a twenty-five thousand man Army and a major expansion of the Navy. Congress authorized a ten-thousand man army and an expansion of the navy, which at the time consisted of one unarmed custom boat.[77][78] Washington was commissioned as senior officer of the army, and Adams reluctantly agreed to Washington's request that Hamilton serve as his second-in-command.[79] The United States engaged

In February 1799, Adams surprised the nation by announcing that he would send a peace mission to France headed by diplomat William Vans Murray.[80] Adams's peace initiative divided his own party between moderate Federalists and the "High Federalists," including Hamilton, who wanted to continue the undeclared war.[81] The prospects for peace were bolstered by the Coup of 18 Brumaire in Paris whereby Napoleon came to power. He viewed the Quasi-War as a distraction from the ongoing war against Britain and its allies in Europe. The Quasi-War ended when both parties signed the Convention of 1800 in September.[82] News of the peace only arrived in the United States after the 1800 election, which Adams lost. Despite opposition by a Federalist pro-war faction, Adams won Senate ratification of the convention in the lame-duck session of Congress.[83] Having concluded the war, Adams demobilized the emergency army.[84]

Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were among the most controversial acts established by the Federalist Party. These acts were four bills passed in 1798 by the Federalist Congress and signed into law by Adams. These acts placed heavy restrictions on immigrants, especially those from France and Ireland, as these were both countries that were predominately Republican. In addition, the Alien and Sedition Acts gave the president greatly expanded powers to imprison or expel such immigrants. This was all part of the attempt to silence their views. Defenders claimed the acts were designed to protect against alien citizens and to guard against seditious attacks from weakening the government. Opponents of the acts attacked on the grounds of being both unconstitutional and as way to stifle criticism of the administration. The Democratic-Republicans also asserted that the acts violated the rights of the states to act in accordance with the Tenth Amendment. None of the four acts did anything to promote national unity against the French or any other country and in fact did a great deal to erode away what unity there already was in the country. The acts in general and the popular opposition to them were all bad luck for John Adams.[85] A key factor in the uproar surrounding the Alien and Sedition Acts was that the very concept of seditious libel was flatly incompatible with party politics. The Republicans, it appears had some understanding of this and realized that the ability to pass judgment on officeholders was essential to party survival. The Federalist Party seemed to have no inkling of this and in some sense seem to be lashing out at the concepts of party in general.[86] What was clear was that the Republicans were becoming more focused in their opposition and more popular with the general population.

The fall of the Federalists

Historian Stephen Kurtz has argued:[87]

- In 1796 Adams stood at the pinnacle of his career. Contemporaries as well as historians ever since have judged him a man of wisdom, honesty, and devotion to the national interest; at the same time, his suspicions and theories led him to fall short of attaining that full measure of greatness for which he longed and labored.... As the nation entered the severe crisis with revolutionary France, and in his attempt to steer the state between humiliating concessions and a potentially disastrous war [he] played a lone hand which left him isolated from increasingly bewildered and better Federalist leaders. His decision to renew peace negotiations after the XYZ Affair, the buildup of armaments, the passage of the Alien and Sedition Acts, and the appointment of Hamilton to command of the army came like an explosion in February 1799. While a majority of Americans were relieved and sympathetic, the Federalist party lay shattered in 1800 on the eve of its decisive conflict with Jeffersonian Republicanism.

Election of 1800

With the Federalist Party deeply split over his negotiations with France, and the opposition Republicans enraged over the Alien and Sedition Acts and the expansion of the military, Adams faced a daunting reelection campaign in 1800.[88] Even so, his position within the party was strong, bolstered by his enduring popularity in New England, a key region for any Federalist presidential victory.[89] Federalist members of Congress caucused in the spring of 1800 and, without indicating a preference, nominated Adams and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney for the presidency.[90] After winning the Federalist nomination, Adams dismissed Hamilton's supporters in the Cabinet. In response, Hamilton publicly attacked Adams and schemed to elect Pinckney as president.[91]

The election hinged on New York: its electors were selected by the legislature, and given the balance of north and south, they would decide the presidential election. Aaron Burr brilliantly organized his forces in New York City in the spring elections for the state legislature. By a few hundred votes he carried the city—and thus the state legislature—and guaranteed the election of a Democratic-Republican President. As a reward he was selected by the Republican caucus in Congress as their vice presidential candidate, with Jefferson as the party's presidential candidate.[92]

Members of the Republican party planned to vote evenly for Jefferson and Burr because they did not want for it to seem as if their party was divided. The party took the meaning literally and Jefferson and Burr tied in the election with 73 electoral votes. This sent the election to the House of Representatives for a contingent election. The Federalists had enough weight in the House to swing the election in either direction. Many would rather have seen Burr in the office over Jefferson, but Hamilton, who had a strong dislike of Burr, threw his weight behind Jefferson.[93]

Historian John E. Ferling attributes Adams' defeat to five factors: the stronger organization of the Democratic-Republicans; Federalist disunity; the controversy surrounding the Alien and Sedition Acts; the popularity of Jefferson in the south; and, the effective politicking of Aaron Burr in New York.[90] Analyzing the causes of the party's trouncing, Adams wrote, "No party that ever existed knew itself so little or so vainly overrated its own influence and popularity as ours. None ever understood so ill the causes of its own power, or so wantonly destroyed them."[94]

Jefferson in power

The transfer of presidential power between Adams and Jefferson represented the first such transfer between two different political parties in U.S. history, and set the precedent for all subsequent presidents from all political parties.[95] The complications arising out of the 1796 and 1800 elections prompted Congress and the states to refine the process whereby the Electoral College elects a president and a vice president. The new procedure was enacted through the 12th Amendment, which became a part of the Constitution in June 1804, and was first followed in that year's presidential election.

Though there had been strong words and disagreements, contrary to the Federalists fears, there was no war and no ending of one government system to let in a new one. Jefferson pursued a patronage policy designed to let the Federalists disappear through attrition. Federalists such as John Quincy Adams and Rufus King were rewarded with senior diplomatic posts, and there was no punishment of the opposition.[96] As president, Jefferson had the power of appointment to fill many government positions that had long been held by Federalists, and he replaced most of the top-level Federalist officials. For other offices, settled on a policy of replacing any Federalist appointee who engaged in misconduct or partisan behavior, with all new appointees being members of the Democratic-Republican Party. Jefferson's refusal to call for a complete replacement of federal appointees under the spoils system was followed by his successors until the election of Andrew Jackson in 1828.[97]

Jefferson had a very successful first term, typified by the Louisiana Purchase, which was supported by Hamilton but opposed by most Federalists at the time as unconstitutional. Some Federalist leaders (see Essex Junto) began courting Burr in an attempt to swing New York into an independent confederation with the New England states, which along with New York were supposed to secede from the United States after Burr's election to Governor. However, Hamilton's influence cost Burr the governorship of New York, a key in the Essex Junto's plan, just as Hamilton's influence had cost Burr the presidency nearly 4 years before. Hamilton's thwarting of Aaron Burr's ambitions for the second time was too much for Burr to bear. Hamilton had known of the Essex Junto (whom Hamilton now regarded as apostate Federalists), and Burr's plans and opposed them vehemently. Hamilton and Burr engaged in a duel in 1804 that ended with Hamilton's death.[98]

The thoroughly disorganized Federalists hardly offered any opposition to Jefferson's reelection in 1804.[99] In New England and in some districts in the middle states the Federalists clung to power, but the tendency from 1800 to 1812 was steady slippage almost everywhere. Some younger Federalist leaders tried to emulate the Democratic-Republican tactics, but their overall disdain of democracy along with the upper class bias of the party leadership eroded public support. In the South, the Federalists steadily lost ground everywhere.[100]

Enduring Federalist judiciary

After being swept out of power in 1800 by Jefferson and the Democratic-Republican Party, Federalists focused their hopes for the survival of the republic upon the federal judiciary. The lame-duck session of the 6th Congress approved the 1801 Judiciary Act, which created a set of federal appeals courts between the district courts and the Supreme Court. As Adams filled these new positions during the final days of his presidency, opposition newspapers and politicians soon began referring to the appointees as "midnight judges." Most of these judges lost their posts when the Democratic-Republican dominated 7th Congress approved the Judiciary Act of 1802, abolishing the newly created courts, and returning the federal courts to its earlier structure.[90][101] Still unhappy with Federalist power on the bench, the Democratic-Republicans impeached district court Judge John Pickering and Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase. Criticizing the impeachment proceedings an attack on judicial independence, Federalist congressmen strongly opposed both impeachments. Pickering, who frequently presided over cases while drunk, was convicted by the Senate in 1804. However, the impeachment proceedings of Chase proved more difficult. Chase had frequently expressed his skepticism of democracy, predicting that the nation would "sink into mobocracy," but he had not shown himself to be incompetent in the same way that Pickering had. Several Democratic-Republican Senators joined the Federalists in opposing Chase's removal, and Chase would remain on the court until his death in 1811. Though Federalists would never regain the political power they had held during the 1790s, the Marshall Court continued to reflect Federalist ideals until the 1830s.[102] After leaving office, John Adams reflected, "My gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life."[103]

See also

References

- Gordon S. Wood, Empire of liberty: a history of the early Republic, 1789–1815 (2009) pp 1–52.

- Krischer, Elana (March 2019). "Review of Berkin, Carol, A Sovereign People: The Crises of the 1790s and the Birth of American Nationalism". H-War, H-Net Reviews. Archived from the original on 2020-09-01. Retrieved 2019-04-03.

- Peter S. Onuf, Jan Lewis, and James P.P. Horn, eds. The Revolution of 1800: Democracy, Race, and the New Republic (U of Virginia Press, 2002).

- Wood, pp. 7-8

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 32–33

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 33–34

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 32–

- Maier, p. 431.

- "Constitution of the United States". National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on August 19, 2011. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- Crew, Harvey W.; William Bensing Webb; John Wooldridge (1892). Centennial History of the City of Washington, D. C. Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House. p. 124.

- Crew, Harvey W.; William Bensing Webb; John Wooldridge (1892). Centennial History of the City of Washington, D. C. Dayton, Ohio: United Brethren Publishing House. pp. 89–92.

- "May 15, 1800: President John Adams orders federal government to Washington, D.C." This Day In History. New York: A&E Networks. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved July 14, 2017.

- Miller 1960, pp. 14–15

- Miller 1960, p. 39

- Ferling 2009, pp. 289–291

- Krom, Cynthia L.; Krom, Stephanie (December 2013). "Whiskey tax of 1791 and the consequent insurrection: "A Wicked and happy tumult"". Accounting Historians Journal. 40 (2): 91–114. doi:10.2308/0148-4184.40.2.91. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2017 – via University of Mississippi Digital Collections.

- Chernow 2004, pp. 341.

- Hogeland 2006, p. 27.

- Chernow 2004, pp. 342–43

- Hogeland 2006, p. 63.

- Slaughter 1986, 100.

- Slaughter 1986, p. 105

- Hogeland 2006, p. 64.

- Ellis 2000, pp. 48–52

- Morison 1965, p. 329

- Ferling 2009, pp. 293–298

- Nussbaum, Arthur (November 1937). "The Law of the Dollar". Columbia Law Review. New York City: Columbia Law School. 37 (7): 1057–1091. doi:10.2307/1116782. JSTOR 1116782.

- Morison 1965, pp. 325

- Ferling 2003, pp. 349–354, 376

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 696–700

- John P. John Adams (2003) pp. 129-137

- Kenneth C. Martis, The Historical Atlas of Political Parties in the United States Congress, 1789–1989 (1989); the numbers are estimates by historians and reflect the percentage of Congressmen who affiliated with the Democratic-Republican Party

- Chambers, Parties in a New Nation, pp. 39–40.

- Miller The Federalist Era 1789–1801 (1960) pp 210–28.

- Gordan S. Wood, The American Revolution: A History (New York: Modern Library, 2003), 158-159.

- Leonard D. White, The Federalists. A Study in Administrative History (1948) p 123.

- Manning J. Dauer, The Adams Federalists, chapter 2.

- L. Marx Renzulli, Maryland: the Federalist years p 142, 183, 295

- Wood, pp. 717-718

- Wood, p. 303

- Wood, pp. 276-277

- Wood, pp. 188, 204

- Wood, pp. 277-279

- Wood, pp. 311-312

- Miller (1960) pp. 155–62

- Thomas P. Slaughter, The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution (1986).

- William Hogeland, The Whiskey Rebellion: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and the Frontier Rebels Who Challenged America's Newfound Sovereignty (2006) excerpt Archived 2019-09-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Wiley Sword, President Washington's Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790–1795 (University of Oklahoma Press, 1985).

- Eid, Leroy V. (1993). "American Indian military leadership: St. Clair's 1791 defeat" (PDF). Journal of Military History. Society for Military History. 57 (1): 71–88. doi:10.2307/2944223. JSTOR 2944223. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-04-17. Retrieved 2017-08-29.

- Morison 1965, pp. 342–343

- Bellfy 2011, pp. 53–55

- Schecter 2010, p. 238

- "May 08, 1792: Militia Act establishes conscription under federal law". This Day In History. New York: A&E Networks. 2009. Archived from the original on July 28, 2017. Retrieved July 20, 2017.

- Barnes 2003, pp. 203–205

- Kent 1918

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, ch 8; Sharp, p. 70 for quote

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 314–16 on Jefferson's favorable responses.

- Marshall Smelser, "The Federalist Period as an Age of Passion," American Quarterly 10 (Winter 1958), 391–459.

- Smelser, "The Jacobin Phrenzy: Federalism and the Menace of Liberty, Equality and Fraternity," Review of Politics 13 (1951) 457–82.

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 451–61

- Eugene R. Sheridan, "The Recall of Edmond Charles Genet: A Study in Transatlantic Politics and Diplomacy". Diplomatic History 18#4 (1994), 463–68.

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 330–65

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 375–406

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 406–50

- Miller (1960) p. 149.

- Todd Estes, "Shaping the politics of public opinion: Federalists and the Jay Treaty debate." Journal of the Early Republic 20.3 (2000): 393–422. in JSTOR Archived 2018-10-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Sharp 113–37.

- Herring 2008, pp. 46–47

- Ferling 2009, pp. 315-17, 345

- Samuel Flagg Bemis, Pinckney's Treaty: A Study of America's Advantage from Europe's Distress, 1783–1800 (1926).

- Raymond A. Young, "Pinckney's Treaty-A New Perspective." Hispanic American Historical Review 43.4 (1963): 526-535. online Archived 2019-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- "Pinckney's Treaty". Mount Vernon, Virginia: Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, George Washington's Mount Vernon. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2017.

- Young, "Pinckney's Treaty"

- Herring 2008, p. 81

- McCullough 2001, pp. 495–96, 502

- Diggins 2003, pp. 96-107

- Diggins 2003, pp. 105-106

- Ralph A. Brown, The Presidency of John Adams (1975) pp. 22-23

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 714–19

- Brown 1975, pp. 112-113, 162

- Wood, pp. 272-274

- E. Wilson Lyon, "The Franco-American Convention of 1800." Journal of Modern History 12.3 (1940): 305-333 online Archived 2019-07-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- Richard C. Rohrs, "The Federalist Party and the Convention of 1800." Diplomatic History 12.3 (1988): 237-260. online Archived 2020-08-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Ferling 1992, ch. 18

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 592–593

- Elkins & McKitrick 1995, pp. 700–701

- Stephen G. Kurtz, "Adams, John" in John A. Garraty, ed., Encyclopedia of American Biography (1974) pp. 12-14.

- Taylor, C. James (4 October 2016). "John Adams: Campaigns and Elections". Charlottesville, Virginia: Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Archived from the original on 16 January 2022. Retrieved August 3, 2017.

- Brown 1975, pp. 176-177

- Ferling 1992, ch. 19

- Wood, pp. 273-275

- Brian Phillips Murphy, "' A Very Convenient Instrument': The Manhattan Company, Aaron Burr, and the Election of 1800." William and Mary Quarterly 65.2 (2008): 233–266. online Archived 2020-07-31 at the Wayback Machine

- John C. Miller, The Federalist Era 1789–1801 (1960) pp 268-77

- Smith 1962, p. 1053

- Diggins 2003, pp. 158-159

- Susan Dunn, Jefferson's second revolution: The Election Crisis of 1800 and the Triumph of Republicanism (2004)

- Appleby, pp. 31-39

- David H. Fischer, "The Myth of the Essex Junto." William and Mary Quarterly (1964): 191–235.

- Lampi, "The Federalist Party Resurgence," p 259

- Manning Dauer, The Adams Federalists (Johns Hopkins UP, 1953).

- Brown 1975, pp. 198–200

- Appleby, pp. 65-69

- Unger, Harlow Giles (November 16, 2014). "Why Naming John Marshall Chief Justice Was John Adams's "Greatest Gift" to the Nation". History News Network. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

Works cited

- Appleby, Joyce (2003). Thomas Jefferson. Times Books.

- Barnes, Celia (2003). Native American Power in the United States, 1783-1795. Teaneck, Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 0-8386-3958-5.

- Bellfy, Philip C. (2011). Three Fires Unity: The Anishnaabeg of the Lake Huron Borderlands. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1348-7.

- Berkin, Carol. A Sovereign People: The Crises of the 1790s and the Birth of American Nationalism. (2017) Online review

- Brown, Ralph A. (1975). The Presidency of John Adams. American Presidency Series. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0134-1.

- Chambers, William Nisbet. Political Parties in a New Nation: The American Experience, 1776–1809 (1963), political science perspective

- Chernow, Ron (2004). Alexander Hamilton. Penguin Books. ISBN 1-59420-009-2.

- Diggins, John P. (2003). Schlesinger, Arthur M. (ed.). John Adams. The American Presidents. New York, New York: Time Books. ISBN 0-8050-6937-2.

- Elkins, Stanley; McKitrick, Eric (1995). The Age of Federalism. Archived from the original on 2012-05-05., the standard highly detailed political history of 1790s; online free to borrow

- Ellis, Joseph J. (2000). Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-375-40544-5.

- Ferling, John E. (1992). John Adams: A Life. University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-0-87049-730-8.

- Ferling, John (2003). A Leap in the Dark: The Struggle to Create the American Republic. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2012-01-03.; survey

- Ferling, John (2009). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-465-0.

- Herring, George (2008). From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507822-0.

- Hogeland, William (2006). The Whiskey Rebellion: George Washington, Alexander Hamilton, and the Frontier Rebels Who Challenged America's Newfound Sovereignty. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-5490-2.

- Kent, Charles A. (1918) [Reprinted from the Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, v. 10, no. 4]. The Treaty of Greenville August 3, 1795. Springfield, Illinois: Schnepp and Barnes. LCCN 19013726. 13608—50.

- Maier, Pauline (2010). Ratification: The People Debate the Constitution, 1787-1788. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0684868547.

- McCullough, David (2001). John Adams. Simon & Schuster. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-4165-7588-7.

- Miller, John C. (1960). The Federalist Era, 1789–1801. New York: Harper & Brothers. LCCN 60-15321.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1965). The Oxford History of the American People. New York: Oxford University Press. LCCN 65-12468.

- Schecter, Barnet (2010). George Washington's America. A Biography Through His Maps. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 978-0-8027-1748-1.

- Sharp, James Roger. American Politics in the Early Republic: The New Nation in Crisis (1993), political narrative of 1790s

- Slaughter, Thomas P. (1986). The Whiskey Rebellion: Frontier Epilogue to the American Revolution. New York City: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505191-2.

- Smith, Page (1962). John Adams. Vol. II 1784–1826. New York: Doubleday. LCCN 63-7188.

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. Oxford University Press.

Further reading

- Banning, Lance. The Jeffersonian Persuasion: Evolution of a Party Ideology (1978) online

- Chambers, William Nisbet, ed. The First Party System (1972

- Hickey, Donald R. "The Quasi-War: America's First Limited War, 1798-1801." The Northern Mariner/Le marin du nord 18.3-4 (2008): 67-77. online

- Miller, John C. The Federalist Era: 1789-1801 (1960), survey of political history

- Taylor, Alan. William Cooper's Town: Power and Persuasion on the Frontier of the Early American Republic. New York: Random House, 1996.

- Varg, Paul A. Foreign Policies of the Founding Fathers (1963). online

- Wood, Gordon S. The American Revolution: A History. New York: Modern Library, 2003.