History of Pennsylvania

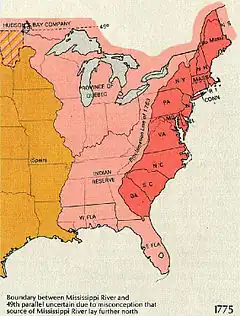

The history of Pennsylvania stems back thousands of years when the first indigenous peoples occupied the area of what is now Pennsylvania. In 1681, Pennsylvania became an English colony when William Penn received a royal deed from King Charles II of England. Although European activity in the region precedes that date (the area was first colonized by the Dutch in 1643). The area was home to the Lenape, Susquehannocks, Iroquois, Erie, Shawnee, Arandiqiouia, and other American Indian tribes. Most of these tribes were driven off or reduced to remnants as a result of diseases, such as smallpox.

The English took control of the colony in 1667. In 1681, William Penn, a Quaker, established a colony based on religious tolerance; it was settled by many Quakers along with its Philadelphia, its largest city, which was also the first planned city. In the mid-1700s, the colony attracted many German and Scots-Irish immigrants.

While each of the Thirteen Colonies contributed to the American Revolution, Pennsylvania and especially Philadelphia were a center for the early planning and ultimately the formation of rebellion against King George III and the British empire, which was then the most powerful political and military empire in the world.

Philadelphia served as the nation's capital for much of the 18th century. During the 19th century, Pennsylvania grew its northwestern, northeastern, and southwestern borders, and Pittsburgh emerged as of the nation's largest and most prominent cities for a period of time. The state played an important role in the Union's victory in the American Civil War. Following the Civil War, Pennsylvania grew into a Republican stronghold politically and a major manufacturing and transportation center.

During the 20th century, after the Great Depression of the 1930s and World War II in the 1940s, Pennsylvania moved towards the service and financial industries economically and became a swing state politically.

History

Native American migration and settlement

.jpg.webp)

Pennsylvania's history of human habitation extends to thousands of years before the foundation of the Province of Pennsylvania. Archaeologists generally believe that the first settlement of the Americas occurred at least 15,000 years ago during the last glacial period, though it is unclear when humans first entered present-day Pennsylvania. There is an open debate in the archaeological community regarding when the ancestors of Native Americans expanded across the two continents to the tip of South America, with the range of estimates being 30,000 and 10,500 years ago.[1] The Meadowcroft Rockshelter contains the earliest known signs of human activity in Pennsylvania, and perhaps all of North America,[2] as it contains the remains of a civilization that existed over 10,000 years ago and possibly pre-dated the Clovis culture.[3][2] By 1000 C.E., in contrast to their nomadic hunter-gatherer ancestors, the native population of Pennsylvania had developed agricultural techniques and a mixed food economy.[4]

Sources for Pennsylvania's prehistory come from a mix of oral history and archaeology, which pushes the known record back another 500 years or so. Before the Iroquois pushed out from the St. Lawrence River region, Pennsylvania appears to have been populated primarily by Algonquians[5] and Siouans. We know from archaeology that the Monongahela had a far more vast territory at the time[6] and the Iroquois Book of Rites shows that there were Siouans along Lake Erie's southern shores as well. The Iroquois collectively called them the Alligewi (better written Adegowe[7]), or Mound Builders. It is said that this is where the term Allegheny comes from (Adegoweni). Two groups of migrating Iroquoians moved through the region—an Iroquois related group who spread west along the Great Lakes and a Tuscarora related group who followed the coast straight south. The Eries were the next to split off from the Iroquois and may have once held northwestern Pennsylvania. An offshoot of them crossed the Ohio and fought back the ancient Monongahela, but later merged with the Susquahannocks to form a single, expanded territory.[8] (Europeans later said that they used the terms White Minqua and Black Minqua to differentiate their ancestries from one another.) A whole other Iroquoian tribe, the Petun, are believed to be Huron related and entered the region after, wedging in between the Eries and Iroquois.

By the time that European colonization of the Americas began, several Native American tribes inhabited the region.[3] The Lenape spoke an Algonquian language, and inhabited an area known as the Lenapehoking, which was mostly made up of the state of New Jersey, but incorporated a lot of surrounding area, including eastern Pennsylvania. Their territory ended somewhere between the Delaware and Susquehanna rivers in the state. The Susquehannock spoke an Iroquoian language and held a region spanning from New York to West Virginia, that went from the area surrounding the Susquehanna River all the way to the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers near present-day Pittsburgh.[9]

European disease and constant warfare with several neighbors and groups of Europeans weakened these tribes, and they were grossly outpaced financially as the Hurons and Iroquois blocked them from proceeding into Ohio during the Beaver Wars. As they lost numbers and land, they abandoned much of their western territory and moved closer to the Susquehanna River and the Iroquois and Mohawk to the north. Northwest of the Allegheny River was the Iroquoian Petun,[10] known mostly for their vast Tobacco plantations, although this is believed to be complete fabrication.[11] They were fragmented into three groups during the Beaver Wars, the Petun of New York, the Wyandot of Ohio, and the Tiontatecaga of the Kanawha River in southern West Virginia. Their size was much larger than previously thought, evidenced by Kentatentonga being used on the Jean Louis Baptiste Franquelin map, a known name for Petun, showing them with Pennsylvania bounds and with 19 villages destroyed and the use of Tiontatecaga, mimicking the Petun autonym, Tionontati.[12] South of the Alleghany River was, allegedly, a nation known as the Calicua (probably Kah-dee-kwuh), or Cali.[13] They may have been the same as the Monongahela Culture and very little is known about them, except that they were probably a Siouan culture. Archaeological sites from this time in this region are scarce and the very few historical sources even mention them—most of these sources only coming from those who met Calicua traders further east on the Allegheny.

A tribe known as the Trokwae were said to have settled by he westernmost Susquehannocks along the Ohio River.[14] They may be the same as the Tockwogh, a small Iroquoian tribe from the Delmarva Peninsula (In many surviving Iroquoian languages, 'r' is silent.). They, however, did not survive the Beaver Wars. During that time, the highly influential Mohawks seceded from the Iroquois Confederacy and the remaining four tribes—Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga and Oneida—began attacking into Ohio, destroying the Petun and other tribes, then the Erie. Later, after their war with the Susquehannocks ended in the 1670s, they pushed straight south from New York and began attacking other tribes of Virginia.[15] In the end, the French pushed the Iroquois back to the Ohio-PA border, where they were finally convinced to sign a peace treaty in 1701. They sold off much of their remaining, extended lands to the English, but kept a large section along the Susquahanna River for themselves, they allowed refugees of other tribes to settle in towns, such as Shamokin, Lenape, Tutelo, Saponi, Piscataway, and Nanticoke.[16][17] Around the onset of the French-Indian War, the English Ambassador to the Iroquois, William Johnson, was able to repair relations between the Iroquois and Mohawk and the nation re-unified. In the 1750s, the refugee tribes were relocated to New York, where they were roughly reorganized along cultural lines into three new Tutelo, Delaware and Nanticoke tribes of the Iroquois Confederacy.[18]

Walking Purchase

In the 1680s, conflicts with the sons of William Penn resulted in the Walking Purchase and after the English conquered the colony of New Netherland, the majority of the Lenape were relocated to northeastern Ohio, immediately prior to that very region being conquered by the French.[19]

Other tribes would pass through, such as the first Shawnee, after they broke away from the Algonquian tribes based in present-day Virginia on the east coast. They soon after merged with other tribes in present-day Ohio, Kentucky, and West Virginia to form a massive confederacy that held much of the eastern Ohio River Valley until the Shawnee Wars in 1811–1813.[3] Like the other indigenous peoples of the Americas, the Native Americans of Pennsylvania suffered from a massive loss in population caused by disease following the beginning of the Columbian Exchange in 1492.[20] The Monongahela culture of southwestern Pennsylvania suffered such large losses that it was nearly extinct by the time Europeans arrived in the region in the 17th century.[21]

European colonization

Long-term European exploration of the Americas commenced after the 1492 expedition of Christopher Columbus, and the 1497 expedition of John Cabot is credited with discovering continental North America for Europeans. European exploration of North America continued in the 16th century, and the area now known as Pennsylvania was mapped by the French and labeled L'arcadia, or "wooded coast", during Giovanni da Verrazzano's voyage in 1524.[22] Even before large-scale European settlement, the Native American tribes in Pennsylvania engaged in trade with Europeans, and the fur trade was a major motivation for the European colonization of North America.[21] The fur trade also sparked wars among Native American tribes, including the Beaver Wars, which saw the Iroquois Confederacy rise in power. In the 17th century, the Dutch, Swedish, and British all competed for southeastern Pennsylvania, while the French expanded into parts of western Pennsylvania.

In 1638, the Kingdom of Sweden, then one of the great powers in Europe, established the colony of New Sweden in the area of the present-day Mid-Atlantic states. The colony was established by Peter Minuit, the former governor of New Netherland, who established the fur trading colony over the objections of the Dutch. New Sweden extended into modern-day Pennsylvania, and was centered on the Delaware River with a capital at Fort Christina (near Wilmington, Delaware). In 1643, New Sweden Governor Johan Björnsson Printz established Fort Nya Gothenburg, the first European settlement in Pennsylvania, on Tinicum Island. Printz also built his own home, The Printzhof, on the island.

In 1609, the Dutch Republic, in the midst of the Dutch Golden Age, commissioned Henry Hudson to explore North America. Shortly thereafter, the Dutch established the colony of New Netherland to profit from the North American fur trade. In 1655, during the Second Northern War, the Dutch under Peter Stuyvesant captured New Sweden. Although Sweden never again controlled land in the area, several Swedish and Finnish colonists remained, and with their influence came America's first log cabins.

The Kingdom of England had established the Colony of Virginia in 1607 and the adjacent Colony of Maryland in 1632. England also claimed the Delaware River watershed based on the explorations of John Cabot, John Smith, and Francis Drake. The English named the Delaware River for Thomas West, 3rd Baron De La Warr, the Governor of Virginia from 1610 until 1618. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1665–1667), the English took control of the Dutch (and former Swedish) holdings in North America. At the end of the Third Anglo-Dutch War, the 1674 Treaty of Westminster permanently confirmed England's control of the region.

Following the voyages of Giovanni da Verrazzano and Jacques Cartier, the French established a permanent colony in New France in the 17th century to exploit the North American fur trade. During the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, the French expanded New France across present day Eastern Canada into the Great Lakes region, and colonized the areas around the Mississippi River as well. New France expanded into western Pennsylvania by the 18th century, as the French built Fort Duquesne to defend the Ohio River valley. With the end of the Swedish and Dutch colonies, the French were the last rivals to the British for control of the region that would become Pennsylvania. France was often allied with Spain, the only other remaining European power with holdings in continental North America. Beginning in 1688 with King William's War (part of the Nine Years' War), France and England engaged in a series of wars for dominance over Northern America. The wars continued until the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, when France lost New France.

Province of Pennsylvania

On March 4, 1681, Charles II of England granted the Province of Pennsylvania to William Penn to settle a debt of £16,000[23] (around £2,100,000 in 2008, adjusting for retail inflation)[24] that the king owed to Penn's father. Penn founded a proprietary colony that provided a place of religious freedom for Quakers. Charles named the colony Pennsylvania ("Penn's woods" in Latin), after the elder Penn, which the younger Penn found embarrassing, as he feared people would think he had named the colony after himself. Penn landed in North America in October 1682, and founded the colonial capital, Philadelphia, that same year.

In addition to English Quakers, Pennsylvania attracted several other ethnic and religious groups, many of whom were fleeing persecution and the religious wars. Welsh Quakers settled a large tract of land north and west of Philadelphia, in what are now Montgomery, Chester, and Delaware counties. This area became known as the "Welsh Tract", and many cities and towns were named for points in Wales. The colony's reputation of religious freedom and tolerance also attracted significant populations of German, Scots-Irish, Scots, and French settlers. Many of the settlers worshiped a brand of Christianity disfavored by the government of their homeland, including Huguenots, Puritans, Calvinists, Mennonites, and Catholics, who migrated to colonial-era Pennsylvania to exercise their religion freely. Other groups, including Anglicans and Jews, migrated to Pennsylvania, while Pennsylvania also had a significant African-American population by 1730. Additionally, several Native American tribes lived in the area under their own jurisdiction. Settlers of Swedish and Dutch colonies that had been taken over by the British continued to live in the region.[3][25]

To give his new province access to the ocean, Penn had leased the proprietary rights of the King Charles II's brother, James, Duke of York, to the "three lower counties" (now the state of Delaware) on the Delaware River. In Penn's Frame of Government of 1682, Penn established a combined assembly by providing for equal membership from each county and requiring legislation to have the assent of both the Lower Counties and the Upper Counties. The meeting place for the assembly alternated between Philadelphia and New Castle. In 1704, after disagreements between the upper and lower counties, the lower counties began meeting in a separate assembly. Province of Pennsylvania and Delaware continued to share the same royal governor until the American Revolutionary War, when both Pennsylvania and Delaware became states.[25]

Penn died in 1718, and was succeeded as proprietor of the colony by his sons. While Penn had won the respect of the Lenape for his honest dealing, Penn's sons and agents were less sensitive to Native American concerns.[21] The 1737 Walking Purchase expanded the colony, but caused a decline in relations with the Lenape.[21] Pennsylvania continued to expand and settle in the areas to the West until the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade all settlers from settling on the western side of the Appalachian Mountains. Meanwhile, Philadelphia became an important port and trading center. The University of Pennsylvania was founded during this period, and Benjamin Franklin established various other organizations such as the American Philosophical Society, the Union Fire Company, and the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. By the start of the American Revolution, Philadelphia was the largest city in British North America.[26]

The western portions of Pennsylvania were among disputed territory between the colonial British and French during the French and Indian War (the North American component of the Seven Years' War). The French had established numerous fortified sites in Pennsylvania, including Fort Le Boeuf, Fort Presque Isle, Fort Machault, and the pivotal Fort Duquesne, located near the present site of Pittsburgh. Many Indian tribes were allied with the French because of their long trading history and opposition to the expansion of the British colonies. The conflict began near the present site of Uniontown, Pennsylvania when a company of Virginia militia under the command of George Washington ambushed a French force at the Battle of Jumonville Glen in 1754. Washington retreated to Fort Necessity and surrendered to a larger French force at the Battle of Fort Necessity. In 1755, the British sent Braddock Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne, but the expedition ended in failure after the British lost the Battle of the Monongahela near present-day Braddock, Pennsylvania. In 1758, the British sent the Forbes Expedition to capture Fort Duquesne. The French won the Battle of Fort Duquesne, but after the battle the outnumbered French force demolished Fort Duquesne and retreated from the area. Fighting in North America had mostly come to an end by 1760, but the war continued until the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1763. Britain's victory in the war helped secure Pennsylvania's frontier, as the Ohio Country came under formal British control. Although New France was no more, the French would deal their British rivals a major blow in the American Revolution by aiding the rebel cause.

During the French and Indian War, Pennsylvania settlers experienced raids from Indian allies of the French. The settlers' pleas for military relief were stymied by a power struggle in Philadelphia between Governor Robert Morris and the Pennsylvania Assembly. Morris wanted to send military forces to the frontier, but the Assembly, whose leadership included Benjamin Franklin, refused to grant the funds unless Morris agreed to the taxation of the proprietary lands, the vast tracts still owned by the Penn family and others. The dispute was finally settled, and military relief sent, when the owners of the proprietary lands sent 5,000 pounds to the colonial government, on condition that it was considered a free gift and not a down payment on taxes.[27]

Shortly after the end of the French and Indian War, Indians attempted to drive the British out of Ohio country in Pontiac's Rebellion. The war, which began in 1763, saw heavy fighting in western Pennsylvania. The native forces were defeated in the Battle of Bushy Run. The war lasted until 1766, when the British made peace. During the war, the king issued the Proclamation Act. The act barred Americans from any settling west of the Appalachians, and reserved that territory for the Native Americans. Fighting between Native Americans and Americans in present-day Pennsylvania continued in Lord Dunmore's War and the Revolutionary War. Native American tribes ceased to pose a military threat to European settlers in Pennsylvania after the conclusion of the Northwest Indian War in 1795.[28]

By the mid-18th century Pennsylvania was basically a middle-class colony with limited deference to the small upper-class. A writer in the Pennsylvania Journal in 1756 summed it up:

- The People of this Province are generally of the middling Sort, and at present pretty much upon a Level. They are chiefly industrious Farmers, Artificers or Men in Trade; they enjoy in are fond of Freedom, and the meanest among them thinks he has a right to Civility from the greatest.[29]

American Revolution

Pennsylvania's residents generally supported the protests common to all Thirteen Colonies after the Proclamation of 1763 and the Stamp Act were passed, and Pennsylvania sent delegates to the Stamp Act Congress in 1765 Philadelphia hosted the first and second Continental Congress.

Gathered in the present-day Independence Hall in Philadelphia, the Second Continental Congress founded the Continental Army, appointed George Washington as its commander, and, on July 4, 1776, unanimously adoption of the Declaration of Independence, which both formalized and escalated the American Revolutionary War.

Pennsylvania was the site of several battles and military activities during the Revolutionary War, including George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River, the Battle of Brandywine, and the Battle of Germantown. During the Philadelphia campaign, the rebel army of George Washington spent the winter of 1777–78 at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. In 1781, the Articles of Confederation were written and adopted in York, Pennsylvania, and Philadelphia continued to serve as the capital of the fledgling nation until the Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783. Notable Pennsylvanians who supported the Revolution include John Dickinson, Robert Morris, Anthony Wayne, Samuel Van Leer, James Wilson, and Thomas Mifflin. However, Pennsylvania was also home to numerous Loyalists, including Joseph Galloway, William Allen, and the Doan Outlaws.[30]

After elections in May 1776 returned old guard Assemblymen to office, the Second Continental Congress encouraged Pennsylvania to call delegates together to discuss a new form of governance. Delegates met in June in Philadelphia, where the signing of the Declaration of Independence soon overtook assemblymen's efforts to control the delegates and the outcome of their discussions. On July 8, 1776, attendees elected delegates to write a state constitution. A committee was formed with Benjamin Franklin as chair and George Bryan and James Cannon as prominent members. The new constitution on September 28, 1776, called for new elections.[31]

Elections in 1776 turned the old assemblymen out of power. But the new constitution lacked a governor or upper legislative house to provide checks against popular movements. It also required test oaths, which kept the opposition from taking office. The constitution called for a unicameral legislature or Assembly. Executive authority rested in a Supreme Executive Council whose members were to be appointed by the assembly. In elections during 1776, radicals gained control of the Assembly. By early 1777, they selected an executive council, and Thomas Wharton Jr. was named as the president of the council. This constitution was never formally adopted, so government functioned on an ad hoc basis until the new constitution was written fourteen years later.

Fall of Philadelphia

After the Continental Army's defeat at the Battle of Brandywine in Chadds Ford Township on September 11, 1777, the revolutionary capital of Philadelphia was left defenseless and American patriots began preparing for what they saw as an imminent British attack on the city. Pennsylvania's Supreme Executive Council ordered that 11 bells, including the State House Bell, now known as the Liberty Bell, and bells from Philadelphia's Christ Church and St. Peter's Church, be taken down and moved out of Philadelphia to protect them from the British, who would melt the bells down to cast into munitions. The bells were transported north to present-day Allentown by two farmers and wagon masters, John Snyder and Henry Bartholomew, and hidden under floorboards in the basement of Zion Reformed Church in what present-day Center City Allentown, just prior to Philadelphia's September 1777 fall to the British.

State and federal constitutions

In 1780, Pennsylvania passed a law that provided for the gradual abolition of slavery, making Pennsylvania the first state to pass an act to abolish slavery, although Vermont had also previously abolished slavery.[32] Children born after that date to slave mothers were considered legally free, but they were bound in indentured servitude to the master of their mother until the age of 28. The last slave was recorded in the state in 1847.

Six years after the adoption of the Articles of Confederation, delegates from across the country met again at the Philadelphia Convention to establish a new constitution. Pennsylvania ratified the U.S. Constitution on December 12, 1787, the second state to do so after Delaware.[33] The Constitution took effect after eleven states had ratified the document in 1788, and George Washington was inaugurated as the first President of the United States on March 4, 1789.

After the passage of the Residence Act, Philadelphia again served as the capital of the nation from 1790 to 1800 prior to the development of Washington, D.C. as the nation's new capital.

Pennsylvania ratified a new state constitution in 1790, which replaced the state's executive council with a governor and a bicameral legislature.

Westward expansion

Pennsylvania's borders took definitive shape in the decades before and after the Revolutionary War. The Mason–Dixon line established the borders between Pennsylvania and Maryland, and was later extended to serve as the border between Pennsylvania and Virginia, except for what is present-day West Virginia's northern panhandle. Although some settlers proposed the creation of the state of Westsylvania in the area that now contains Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania retained control of the region. The first Treaty of Fort Stanwix and the Treaty of Fort McIntosh[28] saw Native Americans relinquish claims on present-day southwestern Pennsylvania. The Treaty of Paris (1783) granted the United States independence, and also saw Great Britain give up its land claims in the neighboring Ohio Country, although most of these lands ultimately became new states under the terms of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. In the second Treaty of Fort Stanwix, Pennsylvania gained control of northwestern Pennsylvania from the Iroquois League. The New York–Pennsylvania border was established in 1787. Pennsylvania purchased the Erie Triangle from the federal government in 1792. In 1799, the Pennamite–Yankee War came to an end, as Pennsylvania kept control of the Wyoming Valley despite the presence of settlers from Connecticut.

After the U.S. government granted land to Revolutionary War soldiers for military service, the Pennsylvania General Assembly passed a general land act on April 3, 1792. It authorized the sale and distribution of the large remaining tracts of land east and west of the Allegheny River in hopes of sparking development of the vast territory. The process was an uneven affair, prompting much speculation but little settlement. Most veteran soldiers sold their shares sight unseen under market value, and many investors were ultimately ruined. The East Allegheny district consisted of lands in Potter, McKean, Cameron, Elk, and Jefferson counties, at the time worthless tracts. West Allegheny district was made up of lands in Erie, Crawford, Warren, and Venango counties, relatively good investments at the time.

Three major land companies participated in the land speculation that followed. Holland Land Company and its agent, Theophilus Cazenove acquired 1,000,000 acres (4,000 km2) of East Allegheny district land and 500,000 acres (2,000 km2) of West Allegheny land from Pennsylvania Supreme Court justice James Wilson. The Pennsylvania Population Company and its president, Pennsylvania State Comptroller General John Nicholson, controlled 500,000 acres (2,000 km2) of land, mostly in Erie County and the Beaver Valley. The North American Land Company and its patron, Robert Morris, held some Pennsylvania lands but was vested mostly in upstate New York, former Iroquois territory.[34]

Whiskey Rebellion

The Whiskey Rebellion, centered in Western Pennsylvania, was one of the first major challenges to the new federal government under the United States Constitution. From 1791 to 1794, farmers rebelled against an excise tax on distilled spirits, and prevented federal officials from collecting the tax. In 1794, President George Washington led a 15,000-soldier militia force into Western Pennsylvania to put down the rebellion, and most rebels returned home before the huge militia force arrived.[35]

19th century

Pennsylvania, one of the largest states in the country, always had the second most electoral votes from 1796 to 1960. From 1789 to 1880, the state only voted for two losing presidential candidates: Thomas Jefferson (in 1796) and Andrew Jackson (in the unusual 1824 election). The Democratic-Republicans dominated the state for most of the First Party System, as the Federalists experienced little success in the state after the 1800 election. Pennsylvania generally supported Andrew Jackson and the Democratic Party in the Second Party System (1828–54), although the Whigs won several elections in the 1840s and 1850s. The Anti-Masonic Party was perhaps Pennsylvania's most successful third party, as it elected Pennsylvania's only third-party governor (Joseph Ritner) and several congressmen in the 1830s.

War of 1812

Several Pennsylvanians fought in the War of 1812, including Jacob Brown, John Barry, and Stephen Decatur. Decatur, who served in both Barbary Wars and the Quasi-War, was one of America's first post-Revolution war heroes. Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry earned the title "Hero of Lake Erie" after building a fleet at Erie, Pennsylvania and defeating the British at the Battle of Lake Erie. Pennsylvanians such as David Conner fought in the Mexican–American War, and Pennsylvania raised two regiments for the war. Pennsylvania Congressman David Wilmot earned national prominence for the Wilmot Proviso, which would have banned slavery in territory acquired from Mexico.[36]

Philadelphia continued to be one of the most populous cities in the country, and it was the second-largest city after New York City for most of the 19th century. In 1854, the Act of Consolidation consolidated the city and county of Philadelphia. The Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia and the Franklin Institute were founded during this period. Philadelphia served as the home of the Bank of North America and its successors, the First and Second Bank of the United States, all three of which served as the central bank of the United States. Philadelphia was also home to the first stock exchange, museum, insurance company, and medical school in the new nation.[26]

Western Pennsylvania development

Settlers continued to cross the Allegheny Mountains. Pennsylvanians built many new roads, and the National Road cut through Southwestern Pennsylvania.[40] Pennsylvania also saw the construction of thousands of miles of rail, and the Pennsylvania Railroad became one of the largest railroads in the world.[40] Pittsburgh grew into an important town West of the Alleghenies, although the Great Fire of Pittsburgh devastated the town in the 1840s. In 1834, Pennsylvania completed construction on the Main Line of Public Works, a railroad and canal system that stretched across southern Pennsylvania, connecting Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. In 1812, Harrisburg was named the capital of the state, providing a more central location than Philadelphia.

Pennsylvania had established itself as the largest food producer in the country by the 1720s, and Pennsylvania agriculture experienced a "golden age" from 1790 to 1840. In 1820, agriculture provided 90 percent of the employment in Pennsylvania. Farm equipment manufacturers sprang up across the state as inventors across the world pioneered new equipment and techniques, and Pennsylvanians such as Frederick Watts were a part of this scientific approach to farming. Pennsylvania farmers lost some of their political power as other industries emerged in the state, but even in the 2000s agriculture remains one of Pennsylvania's major industries.[41]

In 1834, Governor George Wolf signed the Free Schools Act, which created a system of state-regulated school districts. The state created the Department of Education to oversee these schools. In 1857, the Normal School Act laid the foundation for the creation of normal schools to train teachers.[42]

Several Pennsylvania politicians gained national renown. Frederick Muhlenberg of Pennsylvania served as the nation's first Speaker of the House of Representatives. Albert Gallatin served as the Secretary of the Treasury from 1801 to 1814. Democrat James Buchanan, the first and only President of the United States from Pennsylvania, took office in 1857 and served until 1861.

Prior to and during the American Civil War, Pennsylvania was a divided state. Although Pennsylvania had outlawed slavery, there were still Pennsylvanians who believed that the federal government should not interfere with the institution of slavery. One such individual was Democrat James Buchanan, the last pre-Civil War president. Buchanan's party had generally won presidential and gubernatorial elections in Pennsylvania.

1856 and 1860 presidential elections

The nascent Republican Party's first convention took place at Musical Fund Hall on Locust Street in Philadelphia. In the 1860 elections, the Republican Party won the state's presidential vote and the governor's office.

Civil War

After the failure of the Crittenden Compromise, the secession of the South, and the Battle of Fort Sumter, the Civil War began with Pennsylvania as a key member of the Union. Despite the Republican victory in the 1860 election, Democrats remained powerful in the state, and several copperheads called for peace during the war. The Democrats retook control of the state legislature in the 1862 election, but incumbent Republican Governor Andrew Curtin retained control of the governorship in 1863. In the 1864 election, President Lincoln narrowly defeated Pennsylvania native George B. McClellan for the state's electoral votes.[43]

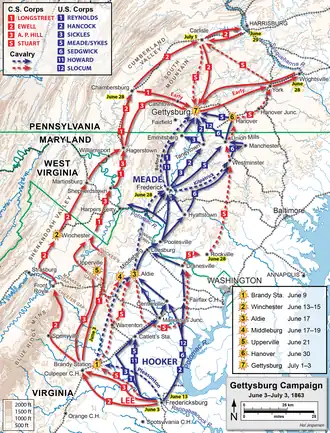

Pennsylvania was the target of several raids by the Confederate States Army. J.E.B. Stuart made cavalry raids in 1862 and 1863; John Imboden raided in 1863 and John McCausland in 1864, when his troopers burned the city of Chambersburg. However, easily the most famous and important military engagement in Pennsylvania was the Battle of Gettysburg, which is considered by many historians as the major turning point of the Civil War. The battle, called "the high water mark of the Confederacy", was a major union victory in the Eastern theater of the war, and the Confederacy was generally on the defensive following the battle. Dead from this battle rest at Gettysburg National Cemetery, established at the site of Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. A number of smaller engagements were also fought in the state during the Gettysburg Campaign, including the battles of Hanover, Carlisle, Hunterstown, and the Fairfield.

Pennsylvania's Thaddeus Stevens and William D. Kelley emerged as leading members of the Radical Republicans, a group of Republicans that advocated winning the war, abolishing slavery, and protecting the civil rights of African-Americans during Reconstruction. Pennsylvania generals who served in the war include George G. Meade, Winfield Scott Hancock, John Hartranft, and John F. Reynolds. Governor Andrew Curtin strongly supported the war and urged his fellow governors to do the same, while former Pennsylvania Senator Simon Cameron served as Secretary of War before his removal.

Post-Civil War

Following the Civil War, the Republican Party exercised strong control over politics in the state, as Republicans won almost every election during the Third Party System (1854–1894) and the Party System (1896–1930). Pennsylvania remained one of the most populous states in the Union, and the state's large number of electoral votes helped Republicans dominate presidential elections from 1860 to 1928. Only once during that period did Pennsylvania vote for a presidential candidate that was not a Republican; the lone exception was former Republican President Theodore Roosevelt in 1912. The Republican Party was nearly as dominant in gubernatorial elections, as Robert E. Pattison was the lone non-Republican to win election as governor between 1860 and 1930. In the 1870s, Pennsylvanians embraced the constitutional reform movement that was sweeping across several states, and Pennsylvania passed a new constitution in 1874.[44] The state created the office of lieutenant governor and made the offices of state auditor and state treasurer into elective offices.[44] The term of the Governor of Pennsylvania was extended to four years, but the governor was prohibited from serving two consecutive terms.[44]

The Pennsylvania Republican party was led by a series of powerful officials, including founder Simon Cameron, his son J. Donald Cameron, Matthew Quay, and Boies Penrose.[45] Quay in particular was one of the dominant political figures of his era, as he served as chairman of the Republican National Committee and helped place Theodore Roosevelt on the 1900 Republican ticket.[46] Following Penrose's death in the 1920s, no one boss dominated the state party, but Pennsylvania Republicans continued to be significantly more powerful than the Democrats until the 1950s.[45] Although the party bosses dominated politics, the Republicans also had a reform movement that challenged their power.[47] Many Pennsylvanians supported the Progressive movement, including Philander C. Knox, Gifford Pinchot, and John Tener.[48] Several new state agencies were established during this time, including the Department of Welfare and the Department of Labor and Industry.[44] Pennsylvanians twice rejected an amendment to the state constitution that would have granted women the right to vote, but the state was one of the first to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment, which granted women the right to vote nationwide.[44]

The era after the Civil War, known as the Gilded Age, saw the continued rise of industry in Pennsylvania. Pennsylvania was home to some of the largest steel companies in the world. Andrew Carnegie founded the Carnegie Steel Company and Charles M. Schwab founded the Bethlehem Steel. Other industry titans, including John D. Rockefeller and Jay Gould, operated in the state. In the latter half of the 19th century, the U.S. oil industry was born in western Pennsylvania, which supplied the vast majority of kerosene for years thereafter. As the Pennsylvanian oil rush developed, the oil boom towns, such as Titusville, rose and fell. Coal mining was also a major industry in the state.

20th century

In 1903, Milton S. Hershey began construction on a chocolate factory in Hershey, Pennsylvania; The Hershey Company would become the largest chocolate manufacturer in North America. The Heinz Company was also founded during this period. These huge companies exercised a large influence on the politics of Pennsylvania; as Henry Demarest Lloyd put it, oil baron John D. Rockefeller "had done everything with the Pennsylvania legislature except refine it".[49][47] Pennsylvania created a Department of Highways and engaged in a vast program of road-building, while railroads continued to see heavy usage.[44]

The growth of industry eventually provided middle-class incomes to working-class households, after the development of labor unions helped them gain living wages. However, the rise of unions led to a rise of union busting, with several private police forces springing up.[49] Pennsylvania was the location of the first documented organized strike in North America, and Pennsylvania experienced the Great Railroad Strike of 1877 and the Coal Strike of 1902. Eventually, the eight-hour day was adopted, and the "coal and iron police" were banned.[50][44] Similarly In 1922, 310,000 Pennsylvania miners went on strike during the UMW General coal strike.[51][52]

During this period, the United States was the destination of millions of immigrants. Previous immigration had mostly come from western and northern Europe, but during this period Pennsylvania experienced heavy immigration from southern and eastern Europe.[44] As many new immigrants were Catholic and Jewish, they changed the demographics of major cities and industrial areas. Pennsylvania and New York received many of the new immigrants, who entered through New York and Philadelphia and worked in the developing industries. Many of these poor immigrants took jobs in factories, steel mills, and coal mines throughout the state, where they were not restricted because of their lack of English. The availability of jobs and public education systems helped integrate the millions of immigrants and their families, who also retained ethnic cultures. Pennsylvania also experienced the Great Migration, in which millions of African Americans migrated from the southern United States to other locations in the United States. By 1940, African Americans made up almost five percent of the state's population.[44]

Even prior to the Civil War in the mid-19th century, Pennsylvania had emerged as a center of scientific discovery, and the state, led by its two major urban centers, continued to be a major place of innovation. The state continued to innovate, as Pennsylvanians invented the first iron and steel t-rails, iron bridges, air brakes, switching signals, and drawn metal wires. Pennsylvanians also contributed to advances in aluminum production, radio, television, airplanes, and farm machinery. During this period, Pittsburgh emerged as an important center of industry and technological innovation, and George Westinghouse became one of the preeminent inventors of the United States.[53] Philadelphia became one of the leading medical science centers in the nation, although it no longer rivaled New York City as a financial capital.[44] Frederick Winslow Taylor pioneered the field of scientific management, becoming America's first "efficiency engineer".[44] In 1890, Chicago had passed Philadelphia as the second most populous city in the United States, while Pittsburgh rose to the eighth spot after annexing Allegheny.

Education continued to be a major issue in the state, and the state constitution of 1874 guaranteed an annual appropriation for education.[44] School attendance became compulsory in 1895, and by 1903, school districts were required to either have their own high schools or pay for their residents to attend another high school.[44] Two of Pennsylvania's largest public schools were founded in the mid-to-late 19th century. The Pennsylvania State University was founded in 1855, and in 1863 the school became Pennsylvania's land-grant university under the terms of the Morrill Land-Grant Acts. Temple University in Philadelphia was founded in 1884 by Russell Conwell, originally as a night school for working-class citizens.

Other colleges and universities, including Bucknell University, Carnegie Mellon University, Drexel University, Duquesne University, La Salle University, Lafayette College, Lehigh University, Saint Francis University, Saint Joseph's University, and Villanova University, were founded in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Western University of Pennsylvania had been operating since 1787; in 1908, it changed its name to the University of Pittsburgh. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School was founded in 1879 as the flagship American Indian boarding school. Thousands of Pennsylvanians volunteered during the Spanish–American War, and many Pennsylvanians fought in the successful campaign against the Spanish in the Philippine Islands. Pennsylvania was an important industrial center in World War I, and the state provided over 300,000 soldiers for the army. Pennsylvanians Tasker H. Bliss, Peyton C. March, and William S. Sims all held important commands during the war. Following the war, the state suffered the effects of the Spanish flu.[44]

Great Depression and World War II

Like much of the rest of the country, Democrats were much more successful in Pennsylvania during the Fifth Party System than they were in the previous two party systems. The Great Depression finally broke the lock on Republican power in the state, as Democrat Franklin Roosevelt won Pennsylvania's electoral votes in all three of his re-election campaigns. Roosevelt was the first Democrat to win the state's electoral votes since James Buchanan in 1856. In 1934, Pennsylvania elected Joseph F. Guffey to the Senate and George Earle III as governor; both individuals were the first Democrats elected to either office in the 20th century. Earle, with the help of a Democratic legislature, passed the "Little New Deal" in Pennsylvania, which included several reforms based on the New Deal and relaxed Pennsylvania's strict Blue laws.[54][55] However, Republicans regained power in the state in the 1938 elections, and Democrats would not win another gubernatorial election until George M. Leader's successful candidacy in 1954.[45]

Earle signed the Pennsylvania State Authority Act in 1936, which would purchase land from the state and add improvements to that land using state loans and grants. The state expected to receive federal grants and loans to fund the project under the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his New Deal. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court, in Kelly v Earle, found the Act violated the state constitution.[56] This prevented the state from receiving federal funds for Works Progress Administration projects and making it difficult to lower the extremely high unemployment rate. Pennsylvania, with its large industrial labor force, suffered heavily during the Great Depression.[44]

Pennsylvania manufactured 6.6 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking sixth among the 48 states.[57] The Philadelphia Naval Yard served as an important naval base, and Pennsylvania produced important military leaders such as George C. Marshall, Hap Arnold, Jacob Devers, and Carl Spaatz.

During World War II, over one million Pennsylvanians served in the United States Armed Forces, and more Medals of Honor were awarded to Pennsylvanians than to individuals from any other state.[44]

Late 20th century

The Republican lock on Pennsylvania was broken in the era after World War II, and Pennsylvania became a somewhat less powerful state in terms of electoral votes and number of House seats. Pennsylvania adopted its fifth and current constitution in 1968; the new constitution established a unified judicial system and allows governors and the other statewide elected officials to serve two consecutive terms.[58]

Between 1954 and 2012, each party consistently won two straight gubernatorial elections before ceding control to the other party. In presidential elections, the Republican Party won Pennsylvania in seven of the eleven elections between 1948 and 1988, but Democrats have won the state in every presidential election from 1992 to 2012. When Democratic presidential nominee Hubert Humphrey won Pennsylvania's electoral votes in 1968, he became the first non-Republican since 1824 to win Pennsylvania's votes without winning the presidential election. After having the second most electoral votes since the 18th century, Pennsylvania was eclipsed in electoral votes by California in 1964. Texas and Florida also now have more electoral votes, while New York also has more electoral votes and Illinois has the same number of electoral votes (and a slightly larger population).

As of 2014, Pennsylvania is generally considered to be an important swing state in both presidential and congressional elections, and Pennsylvania has a Cook PVI of D+1. Since the 1990s, Republicans have usually controlled both houses of the legislature, while candidates from both parties have been elected to the statewide offices of governor, lieutenant governor, attorney general, treasurer, and auditor general. Democrats generally win the cities and Republicans win the rural areas, with the suburbs voting for both parties and often acting as the key swing areas.[59]

Steel industry declines

The state experience significant economic decline with the demise of the state's steel industry and other heavy industries, which began in the late 20th century and intensified in the 1980s. With job losses came heavy population losses, especially in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh. With the end of mining and the downturn of manufacturing, the state has turned to service industries. Pittsburgh's concentration of universities has enabled it to be a leader in technology and healthcare. Philadelphia has a concentration of university expertise. Healthcare, retail, transportation, and tourism are some of the state's growing industries of the postindustrial era. Like much of the rest of the nation, most residential population growth has occurred in suburban rather than urban areas, although both of the state's major cities have had significant revitalization of their downtown areas.[60]

After 1990, as information-based industries became more important in the economy, state and local governments put more resources into the old, well-established public library system. Some localities, however, used new state funding to cut local taxes.[61] New ethnic groups, especially Hispanics, began entering the state to fill low skill jobs in agriculture and service industries. For example, in Chester County, Mexican migrants brought their Spanish language and cuisine when they were hired as agricultural laborers.[62] Meanwhile, Puerto Ricans built a large community in the state's third-largest city, Allentown, becoming forty percent of the city's population by 2000.[63]

21st century

On September 11, 2001, during the terrorist attacks on the United States, the small town of Shanksville, Pennsylvania received worldwide attention after United Airlines Flight 93 crashed into a field in Stonycreek Township, 1.75 miles (2.82 km) north of the town, killing all 40 civilians and four al-Qaeda hijackers on board. The hijackers had intended to fly the plane to Washington, D.C. and crash it into either the Capitol or the White House.

After learning from family members via airphone of the earlier attacks on the World Trade Center, the passengers on board revolted against the hijackers and fought for control of the plane, causing it to crash. It was the only one of the four aircraft hijacked that day that never reached its intended target and the heroism of the passengers has been commemorated.[64]

Urban centers

Philadelphia is the nation's sixth-largest city after New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Houston, and Phoenix. Philadelphia anchors the nation's sixth-largest metropolitan area. known as the Delaware Valley. Pittsburgh is the center of Greater Pittsburgh, the nation's 22nd-largest metropolitan area. In eastern Pennsylvania, the Lehigh Valley has grown to the nation's 68th-largest metropolitan area as of 2020.[65] Pennsylvania also has six other metropolitan areas that rank among the nation's 200-largest metropolitan areas. Philadelphia is the second-largest city in the Northeast megalopolis after New York City and a core population center in the Northeastern United States. Pittsburgh, the state's second-largest city, is part of the Great Lakes Megalopolis and is often associated with the Midwestern United States. Both Allentown and Pittsburgh are considered part of the Rust Belt, a region of the United States negatively impacted by deindustrialization in the late 20th century.

See also

- Education in Pennsylvania

- History of Erie, Pennsylvania

- History of Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

- History of the Mid-Atlantic States

- History of the Northeastern United States

- History of Philadelphia

- History of Pittsburgh

- History of slavery in Pennsylvania

- History of the Townships of Lycoming County, Pennsylvania

- History of West Chester, Pennsylvania

- History of Williamsport, Pennsylvania

- Jewish history in Pennsylvania

- List of historical Pennsylvania women

- List of newspapers in Pennsylvania in the 18th-century

- List of Pennsylvania suffragists

- Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission

- Pennsylvania Woman's Convention at West Chester in 1852

- Timeline of Philadelphia

- Timeline of Pittsburgh

- Women's suffrage in Pennsylvania[66]

References

- "Paleoindian Period – 16,000 to 10,000 years ago". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- Ancient Pa. Dwelling Still Dividing Archaeologists

- "Pennsylvania on the Eve of Colonization". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- "Late Woodland Period in the Susquehanna and Delaware River Valleys". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- Johnson, Basil The Manitous: The Spiritual World of the Ojibway. 1995

- Bloemker, James D. An Overview of Historical Archaeology in West Virginia 1988.

- Froman, Francis and Keye, Alfred J. English-Cayuga/Cayuga-English Dictionary 2014.

- Hale, Horatio The Iroquois Book of Rites 1884.

- "On the Susquehannocks: Natives having used Baltimore County as hunting grounds – The Historical Society of Baltimore County". www.HSOBC.org. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- "Early Indian Migration in Ohio". GenealogyTrails.com. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- Garrad, Charles "Petun and the Petuns"

- Louis, Franquelin, Jean Baptiste. "Franquelin's map of Louisiana". LOC.gov. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- (Extrapolation from the 16th-century Spanish, 'Cali' ˈkali a rich agricultural area – geographical sunny climate. also 1536, Cauca River, linking Cali, important for higher population agriculture and cattle raising and Colombia's coffee is produced in the adjacent uplands. Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. 'Cali', city, metropolis, urban center. Pearson Education 2006. "Calica", Yucatán place name called rock pit, a port an hour south of Cancún. Sp. root: "Cal", limestone. Also today, 'Calicuas', supporting cylinder or enclosing ring, or moveable prop as in holding a strut)

- http://www.ontarioarchaeology.on.ca/.../Publications/oa51-2-steckley.pdf%5B%5D

- "Lambreville to Bruyas Nov. 4,1696" N.Y. Hist. Col. Vol. III, p. 484

- N.Y. Hist. Col. Vol. V, p. 633

- "Life of Brainerd" p. 167

- N.Y. Hist. Col. Vol. VI, p. 811

- "Brief History of the Lenape". LenapeDelawareHistory.net. Retrieved August 17, 2017.

- Snow, Dean R. (1996). "Mohawk demography and the effects of exogenous epidemics on American Indian populations". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 15 (2): 160–182. doi:10.1006/jaar.1996.0006.

- "Contact Period (1500–1763)". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

- "16th Century Pennsylvania Maps", mapsofpa.com.

- Pennsylvania Society of Colonial Governors, ed. (1916). "Samuel Carpenter". Pennsylvania Society of Colonial Governors, Volume 1. pp. 180–181.

- "Measuring Worth". Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2010.

- "The Quaker Province: 1681–1776". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- "The American Revolution". Explore PA History. WITF. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- Parkman, Francis. Montcalm and Wolfe (1884). Reprinted in France and England in North America, Volume 2, New York: The Library of America, 1983. pp. 1076–1083.

- "Chapter 4: Dispossession, Dispersal, and Persistence". Explore PA History.com. Retrieved December 2, 2014.

- Clinton Rossiter, Seedtime of the Republic: the origin of the American tradition of political liberty (1953) p. 106.

- Middlekauff, Robert. The Glorious Cause: The American Revolution, 1763–1789 (1985), p. 550.

- "Pennsylvania Constitution" Archived April 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Doc Heritage website

- "Constitution of Vermont (1777)". Chapter I, Article I: State of Vermont. 1777. Retrieved June 7, 2014.

- Pennsylvania ratifies the Constitution of 1787

- Buck, Solon J. and Elizabeth Hawthorn Buck. The Planting of Civilization in Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1939. 2nd paperback reprint, 1979, pp. 206–213; Stevens, Sylvester K. Pennsylvania: The Heritage of a Commonwealth, Vol. I, West Palm Beach: American Historical Co., 1968, pp. 323–325; Bausman, Joseph Henderson. History of Beaver County, Pennsylvania and Its Centennial Celebration, Knickerbocker Press, 1904, p. 1230

- Wood, Gordon S. (2009). Empire of Liberty. Oxford University Press. pp. 134–139. ISBN 978-0-19-503914-6.

- "From Independence to the Civil War: 1776–1861". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- "Ultrarare photo of Abraham Lincoln discovered". Fox News. September 24, 2013. Archived from the original on September 25, 2013. Retrieved September 25, 2013.

- Lidz, Franz (October 2013). "Will the Real Abraham Lincoln Please Stand Up?". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- Brian, Wolly (October 2013). "Interactive: Seeking Abraham Lincoln at the Gettysburg Address". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on September 29, 2013. Retrieved October 3, 2013.

- "Crossing the Alleghenies". Explore PA History. WITF. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- "Agriculture and Rural Life". Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- "Chapter Two: Staying the "Battle Axe of Ignorance": The Rise of Public Education". Explore Pa History.com. WITF. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- "Chapter One: Pennsylvania Democrats". Explore PAHistory.com. WITF. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- "The Era of Industrial Ascendancy: 1861–1945". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- Morgan, Alfred L. (April 1978). "The Significance of Pennsylvania's 1938 Gubernatorial Election". Pennsylvania's 1938 Election. pp. 184–210. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- Reichley, A. James (2000). The Life of the Parties. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 127–131.

- "Chapter One: 1. Pennsylvania's Bosses and Political Machines". Explore PA History.com. WITF. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- "Chapter Four: From the Progressive Era to the Great Depression". Explore PAHistory.com. WITF. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- "Chapter 2: Pennsylvania Under the Reign of Big Business". Explore PAHistory.com. WITF. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- "Overview: Labor's Struggle to Organize". Explore PAHistory.com. WITF. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- Humanities, National Endowment for the (August 5, 1922). "The labor world. [volume] (Duluth, Minn.) 1896-current, August 05, 1922, Image 1" – via chroniclingamerica.loc.gov.

- Zimand. "Labor Age". Labor Age. pp. 4–7, 15–17. Retrieved March 2, 2023.

- "Overview: Science and Invention". Explore PAHistory.com. WITF. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- "Governor George Howard Earle III". State historic preservation office. Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- "George H. Earle III Historical Marker". Explore PA History.com. WITF. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- "Pennsylvania State Authority Act", R. L. T., University of Pennsylvania Law Review and American Law Register, Vol. 85, No. 5 (Mar. 1937), p. 518

- Peck, Merton J. and Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p. 111

- "Maturity: 1945–2011". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- Cohen, Micah (October 29, 2012). "In Pennsylvania, the Democratic Lean Is Slight, but Durable". Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- Ashok K. Dutt, and Baleshwar Thakur, City, Society, and Planning (Concept Publishing Company, 2007) pp. 55–56

- William F. Stine, "Does State Aid Stimulate Public Library Expenditures? Evidence from Pennsylvania's Enhancement Aid Program" Library Quarterly (2006) 76#1 107–139.

- Victor M. Garcia, "The Mushroom Industry And The Emergence Of Mexican Enclaves In Southern Chester County, Pennsylvania, 1960–1990" Journal of Latino-Latin American Studies (JOLLAS) (2005) 1#4 pp 67–88.

- Gilbert Marzan, "Still Looking for that Elsewhere: Puerto Rican Poverty and Migration in the Northeast." Centro Journal (2009) 21#1 pp 100–117 online.

- Alexander Riley, Angel patriots: The crash of United Flight 93 and the myth of America (NYU Press, 2015) pp 1–34.

- Kraus, Scott. "No end in sight to Valley's population growth". Retrieved December 1, 2014.

- Federal Writers' Project (1940), "Chronology", Pennsylvania: a Guide to the Keystone State, American Guide Series, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 9781603540377 – via Google Books

Further reading

Surveys

- Miller, Randall M. and William A. Pencak, eds. Pennsylvania: A History of the Commonwealth (2002) detailed scholarly history

- Beers, Paul B. Pennsylvania Politics Today and Yesterday (1980)*

- Klein, Philip S and Ari Hoogenboom. A History of Pennsylvania (1973).

- Weigley, Russell. Philadelphia: A 300-Year History (1982)

Pre 1900

- Alexander, John K. Render them Submissive: Responses to Poverty in Philadelphia, 1760–1800 (1980)

- Baldwin, Leland D. Pittsburgh: the Story of a City, 1750–1865 (1937).

- Barr, Daniel P. A Colony Sprung from Hell: Pittsburgh and the Struggle for Authority on the Western Pennsylvania Frontier, 1744–1794 (Kent State University Press, 2014); 334 pp.

- Buck, Solon J., Clarence McWilliams and Elizabeth Hawthorn Buck. The Planting of Civilization in Western Pennsylvania (1939), social history

- Dunaway, Wayland F. The Scotch-Irish of Colonial Pennsylvania (1944)

- Gallman, J. Matthew. Mastering Wartime: A Social History of Philadelphia during the Civil War (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2000).

- Higginbotham, Sanford W. The Keystone in the Democratic Arch: Pennsylvania Politics, 1800–1816 (1952)

- Illick Joseph E. Colonial Pennsylvania: A History (1976)

- Ireland, Owen S. Religion, Ethnicity, and Politics: Ratifying the Constitution in Pennsylvania (1995)

- Kehl, James A. Boss Rule in the Gilded Age: Matt Quay of Pennsylvania

- Klees, Fredric. The Pennsylvania Dutch (1950)

- Klein, Philip Shriver. Pennsylvania Politics, 1817–1832: A Game without Rules (1940)

- McCullough, David. The Johnstown Flood (1968)

- Mueller, Henry R. The Whig Party in Pennsylvania (1922)

- Nash, Gary B. Forging freedom: The formation of Philadelphia's black community, 1720–1840 (Harvard University Press, 1988).

- Shade, William G. "'Corrupt and Contented': Where Have All the Politicians Gone? A Survey of Recent Books on Pennsylvania Political History, 1787–1877." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (2008): 433–451. in JSTOR; historiography

- Smith, Billy Gordon. The "Lower Sort": Philadelphia's Laboring People, 1750–1800 (Cornell University Press, 1994).

- Snyder, Charles McCool. The Jacksonian Heritage: Pennsylvania Politics, 1833–1848 (1958)

- Tinkcom, Harry Marlin. The Republicans and Federalists in Pennsylvania, 1790–1801: A Study in National Stimulus and Local Response (1950)

- Warner, Sam Bass. The Private City: Philadelphia in Three Periods of its Growth (1968)

- Wood, Ralph. et al. The Pennsylvania Germans (1942)

- Wulf, Karin. Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia. Cornell University Press, 2000

Since 1900

- Bodnar, John; Immigration and Industrialization: Ethnicity in an American Mill Town, 1870–1940, (1977), on Steelton

- Heineman; Kenneth J. A Catholic New Deal: Religion and Reform in Depression Pittsburgh, (1999)

- Keller, Richard C., "Pennsylvania's Little New Deal", in John Braeman et al. eds. The New Deal: Volume Two – the State and Local Levels (1975) pp. 45–76

- Lamis, Renée M. The Realignment of Pennsylvania Politics since 1960: Two-Party Competition in a Battleground State (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009) 398 pp. ISBN 978-0-271-03419-5

- Lubove, Roy. Twentieth-century Pittsburgh: The post-steel era. Vol. 2. University of Pittsburgh Pre, 1995.

- McGeary, M. Nelson. Gifford Pinchot: Forester-Politician (1960) Republican governor 1923–1927 and 1931–1935

- Sandoval, Edgar. The New Face of Small-town America: Snapshots of Latino Life in Allentown, Pennsylvania (Penn State Press, 2010).

- Warner, Sam Bass. The Private City: Philadelphia in Three Periods of its Growth (1968)

Economic and labor history

- Aurand, Harold W. Coalcracker Culture: Work and Values in Pennsylvania Anthracite, 1835–1935 2003

- Blatz, Perry. Democratic Miners: Work and Labor Relations in the Anthracite Coal Industry, 1875–1925. Albany: SUNY Press, 1994.

- Binder, Frederick Moore. Coal Age Empire: Pennsylvania Coal and Its Utilization to 1860. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1974.

- Chandler, Alfred. "Anthracite Coal and the Beginnings of the 'Industrial Revolution' in the United States", Business History Review 46 (1972): 141–181. in JSTOR

- Churella, Albert J. (2013). The Pennsylvania Railroad: Volume I, Building an Empire, 1846–1917. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-4348-2. OCLC 759594295.

- Davies, Edward J., II. The Anthracite Aristocracy: Leadership and Social Change in the Hard Coal Regions of Northeastern Pennsylvania, 1800–1930 (1985).

- DiCiccio, Carmen. Coal and Coke in Pennsylvania. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1996

- Dublin, Thomas, and Walter Licht, The Face of Decline: The Pennsylvania Anthracite Region in the Twentieth Century Cornell University Press, (2005). ISBN 0-8014-8473-1.

- Lauver, Fred J. "A Walk Through the Rise and Fall of Anthracite Might", Pennsylvania Heritage Magazine 27#1 (2001) online edition

- Lewis, Ronald L. Welsh Americans: A History of Assimilation in the Coalfields (U. of North Carolina Press, 2008) online

- Powell, H. Benjamin. Philadelphia's First Fuel Crisis. Jacob Cist and the Developing Market for Pennsylvania Anthracite. The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1978

- Sullivan, William A. The Industrial Worker in Pennsylvania, 1800–1840 Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1955 online edition

- United States Anthracite Coal Strike Commission, 1902–1903, Report to the President on the Anthracite Coal Strike of May–October 1902 By United States Anthracite Coal Strike (1903) online edition

- Wallace, Anthony F.C. St. Clair. A Nineteenth-Century Coal Town's Experience with a Disaster-Prone Industry. (1981)

- Warren, Kenneth. Triumphant Capitalism: Henry Clay Frick and the Industrial Transformation of America (1996)

- Warren, Kenneth. Big Steel: The First Century of the United States Steel Corporation, 1901–2001 (2002)

- Williamson, Harold F. and Arnold R. Daum. The American Petroleum Industry: The Age of Illumination, 1859–1899 (1959)

Historiography

- Bauman, John F. "An urban look at Pennsylvania history" Pennsylvania History (2008) 75#3 pp 390–395. online

Primary sources

- The Peoples Contest: A Civil War era digital archiving project, access to primary sources from Pennsylvania, especially newspapers and other resources

- Report of the United states coal commission.... (5 vol in 3; 1925) Official US government investigation of the 1922 anthracite strike. online vol 1–2

- Carocci, Vincent P. A Capitol Journey: Reflections on the Press, Politics, and the Making Of Public Policy In Pennsylvania. (2005) memoir by senior aide to Gov Casey in 1990s excerpts online

- Martin, Asa Earl, and Hiram Herr Shenk, eds. Pennsylvania history told by contemporaries (Macmillan, 1925) online.

- Myers, Albert Cook, ed., Narratives of Early Pennsylvania, West New Jersey and Delaware, 1630–1707, (1912) online

- Pinsker, Matthew. "The Pennsylvania Prince: Political Wisdom From Benjamin Franklin to Arlen Specter" Pennsylvania Magazine of History & Biography (2008) 132#4 pp 417–432; examines autobiographies. online

External links

- ExplorePAHistory.com

- Pennsylvania state archives website

- View the Pennsylvania State Archives Online

- Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Publications

- 1776 Constitution text

- Pennsylvania Indian Tribes Listing of Indian tribes with a historical presence in Pennsylvania

- Boston Public Library, Map Center. Maps of Pennsylvania, various dates

- Ohio Historical Sites