Pennsylvania in the American Revolution

Pennsylvania was the site of many key events associated with the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War. The city of Philadelphia, then capital of the Thirteen Colonies and the largest city in the colonies, was a gathering place for the Founding Fathers who discussed, debated, developed, and ultimately implemented many of the acts, including signing the Declaration of Independence, that inspired and launched the revolution and the quest for independence from the British Empire.

Founding Father Robert Morris said, "You will consider Philadelphia, from its centrical situation, the extent of its commerce, the number of its artificers, manufactures and other circumstances, to be to the United States what the heart is to the human body in circulating the blood."[2]

The American Revolution included both the political and social development of the Thirteen Colonies of British America, and the Revolutionary War. John Adams wrote to Thomas Jefferson in 1815: "What do we mean by the revolution? The war? That was no part of the revolution. It was only an effect and consequence of it. The revolution was in the minds of the people, and this was effected, from 1760 to 1775, in the course of fifteen years before a drop of blood was drawn at Lexington. The records of thirteen legislatures, the pamphlets, newspapers in all the colonies ought be consulted, during that period, to ascertain the steps by which the public opinion was enlightened and informed concerning the authority of parliament over the colonies."[3]

Military

- First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry - The oldest continuously serving unit in the United States military

- Pennsylvania Line of the Continental Army

- Pennsylvania Militia Units

- Pennsylvania Navy

Government

Key events

- Philadelphia Tea Party (October 16, 1773)

- First Continental Congress (September 5 to October 26, 1774)

- Continental Association created (October 20, 1774)

- Petition to the King ratified (October 25, 1774)

- Second Continental Congress (convened on May 10, 1775)

- Hanna's town resolves (May 16, 1775)

- Olive Branch Petition (July 1775)

- Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms (July 1775)

- Continental Marines formed by act of Congress (November 10, 1775) with the following decree:[4]

That two battalions of Marines be raised consisting of one Colonel, two lieutenant-colonels, two majors and other officers, as usual in other regiments; that they consist of an equal number of privates as with other battalions, that particular care be taken that no persons be appointed to offices, or enlisted into said battalions, but such as are good seamen, or so acquainted with maritime affairs as to be able to serve for and during the present war with Great Britain and the Colonies; unless dismissed by Congress; that they be distinguished by the names of the First and Second Battalions of Marines.

- Pennsylvania Provincial Conference (June 18–25, 1776)

- The Lee Resolution (also known as "The Resolution for Independence") (July 2, 1776)

- Declaration of Independence (1776)

- George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River (December 25, 1776) to attack the Crown Forces' German auxiliaries at Trenton. The decisive American victory was a significant morale boost to the demoralized, shrinking American army that was teetering on collapse due to impending enlistment expirations. The American victory at Trenton, together with American victories at the Battle of the Assunpink Creek and the Battle of Princeton helped inspire the Patriots and keep the Continental Army intact.

- Continental Congress adopts the 13-star US flag: "Resolved, That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation."[5] (June 14, 1777)

- Philadelphia campaign (1777–1778)

- Conway Cabal (1777–1778)

- Battle of Brandywine (September 11, 1777) - the largest battle of the American Revolution by number of troops engaged, and the longest single-day battle of the war, with continuous fighting for 11 hours

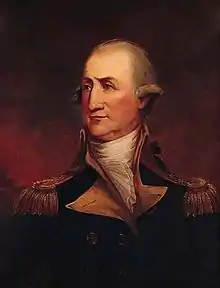

- During the battle, famed British army marksman Patrick Ferguson, leading the Experimental Rifle Corps equipped with fast breech-loading Ferguson rifles, had the chance to shoot a prominent American officer, accompanied by another in distinctive hussar dress, but decided not to do so, as the man had his back to him (Ferguson) and was unaware of his presence. A surgeon told Ferguson in the hospital that some American casualties had said that General Washington had been in the area at the time. Ferguson wrote that, even if the officer were the general, he did not regret his decision.[6] The officer's identity remains uncertain; historians suggest that the aide in hussar dress might indicate the senior officer was Count Casimir Pulaski.

- Brandywine was the first battlefield command of Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette. The American retreat was well-organized, largely due to his efforts. Although wounded, he created a rally point that allowed for a more orderly retreat before being treated for his wound.[7] Lafayette returned to visit Brandywine during his Grand tour of the United States in 1824–25, after which he was returned to France aboard the USS Brandywine.[8]

- In addition to Lafayette, Polish Count Casimir Pulaski was another foreign officer present at Brandywine — his first military engagement against the British.[9] When the Continental Army troops began to yield, he reconnoitered with Washington's bodyguard of about 30 men, and reported that the enemy were endeavoring to cut off the line of retreat.[10] Washington ordered him to collect, as many as possible, the scattered troops who came his way, and employ them according to his discretion to secure the retreat of the army.[11] His subsequent charge averted a disastrous defeat of the Continental Army cavalry,[10][9][12] earning him fame in America[13] and saved the life of George Washington.[14] As a result, on September 15, 1777, on the orders of Congress, Washington made Pulaski a brigadier general in the Continental Army cavalry.[15] At that point, the cavalry was only a few hundred men strong organized into four regiments. These men were scattered among numerous infantry formations, and used primarily for scouting duties. Pulaski immediately began work on reforming the cavalry, and wrote the first regulations for the formation.[9]

- Battle of the Clouds (September 16, 1777) - an aborted engagement in the area surrounding present day Malvern, Pennsylvania. After the American defeat at the Battle of Brandywine, the British Army remained encamped near Chadds Ford. When British commander William Howe was informed that the weakened American force was less than ten miles (16 km) away, he decided to press for another decisive victory. George Washington learned of Howe's plans, and prepared for battle. Before the two armies could fully engage, a torrential downpour ensued. Significantly outnumbered, and with tens of thousands of cartridges ruined by the rain, Washington opted to retreat. Bogged down by rain and mud, the British allowed Washington and his army to withdraw. The storm, which historian Thomas McGuire describes as "a classic nor'easter," raged well into the next day.[16]

- Battle of Paoli (Also known as the Paoli Massacre) (September 20, 1777)

- Siege of Fort Mifflin (September 26 to November 16, 1777)

- Explosion and destruction of HMS Augusta - an explosion that smashed windows in Philadelphia and was heard 30 miles (48 km) away (October 22, 1777)

- Battle of Germantown (October 4, 1777)

- Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union created (November 15, 1777)

- Battle of White Marsh (December 5–8, 1777)

- Battle of Matson's Ford (December 11, 1777)

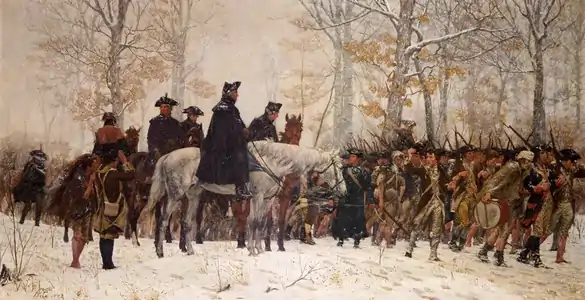

- Valley Forge winter encampment of the Continental Army (December 1777 to June 1778)

- Battle of Crooked Billet (May 1, 1778)

- The Meschianza (May 18, 1778) - an elaborate fête given in honor of British General Sir William Howe in Philadelphia on May 18, 1778

- Battle of Barren Hill (May 20, 1778)

- Carlisle Peace Commission (1778)

- The Big Runaway (June and July 1778)

- Wyoming Valley battle and massacre (July 3, 1778)

- Treaty of Fort Pitt (September 17, 1778) - the first written treaty between the new United States of America and any American Indians—the Lenape (Delaware Indians) in this case

- An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery (March 1, 1780) passed by the Pennsylvania legislature - one of the first attempts by a government in the Western Hemisphere to begin an abolition of slavery

- Sugarloaf Massacre (September 11, 1780)

- Pennsylvania Line Mutiny (January 1, 1781)

- Convention Army moved to Pennsylvania in 1781 (1781 to 1783) - an army of British and allied troops captured after the Battles of Saratoga. They were held prisoner at Camp Security in York County, PA. Located in present-day Springettsbury Township.

- Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783 (June 20, 1783)

Key historical sites, museums, and institutions

Battlefields

- Battle of Brandywine, parts of the vast battlefield, largely on private property, are preserved as municipal parks, trail easements, and preservation easements:

- Birmingham Hill (Chadds Township), established in 2010, the footpath at Birmingham Hill allows public access to a portion of the Brandywine Battlefield. The Footpath follows a 1.1 mile trail.

- Birmingham Friends Meetinghouse, across the street from the Birmingham Hill trail. During the Battle of Brandywine, British forces attempted to flank the Continental Army under General George Washington. The Continental forces rushed north to meet the British in the area of the meetinghouse. It was used as a hospital first for the Americans, and after the battle for British officers. The stone wall around the cemetery was used as a defensive position by the Americans. After the battle, dead British and American soldiers shared a common grave in the cemetery, which is now marked by a memorial stone.

- Sandy Hollow Heritage Park (Birmingham Township), 42 acres of preserved open space, much as it was in 1777, allows public access for passive recreation to a portion of the Brandywine Battlefield National Historic Landmark. Established in 2002, the park has a 1.1 mile asphalt path for pedestrians.

- John Chads House, historic house on the battlefield - near the beginning of the battle. Artillery fire was exchanged by both sides around the house.[17]

- Dilworthtown, site of the end of the battle

- William Brinton 1704 House, fighting and troop movements at the end of battle occurred around this house

- Brandywine Battlefield Historic Site (Delaware and Chester Counties), historic park and museum that includes headquarters locations of Generals Washington and Lafayette from the Battle of Brandywine (September 11, 1777)

- Battle of Germantown

- Cliveden (Benjamin Chew House) (Philadelphia, PA), site of part of the Battle of Germantown (1777)

- Wyck House, served as a hospital during the battle

- Peter Wentz Homestead, historic site that served as headquarters for General George Washington before and after the Battle of Germantown, October 2–4 and 16–21, 1777

- Siege of Fort Mifflin

- Fort Mifflin, Philadelphia site of the Siege of Fort Mifflin, which delayed the entry of the British Navy into the Port of Philadelphia, allowing the successful repositioning of the Continental Army for the Battle of White Marsh and subsequent withdrawal to Valley Forge. Modified over time for changing needs of the Army, some of the original Revolutionary War walls are preserved in the fort's expanded walls. Marks from artillery that sieged the fort are visible.

- Battle of Paoli (Paoli Massacre)

- Paoli Battlefield Historical Park in Malvern, site of the Paoli Massacre

- Battle of White Marsh

- Fort Washington State Park, preserves part of the site of the Battle of White Marsh

- Battle of Wyoming (also known as the Wyoming Valley Massacre)

- Wyoming Monument, monument located at the battle site

Museums, parks and other historic sites

- Camp Security Park (Springettsbury Township, York County, PA), site of the 1781 to 1783 Prisoner of War camp for prisoners from the Convention Army taken at the Battles of Saratoga - Crown forces (largely German auxiliaries - commonly called "Hessians").

- Carpenters' Hall (Philadelphia, PA), meeting site of First Continental Congress (1774).

- Fort Pitt Museum (Pittsburgh, PA)

- George Taylor House (Catasauqua, PA)

- Gen. Horatio Gates House and Golden Plough Tavern (York, PA), historic site and interpretive center centered around the Continental Congress's temporary relocation from Philadelphia to York, where the Articles of Confederation were drafted and adopted.

- Graeme Park (Horsham, Montgomery County, PA), including the Keith House, the only surviving residence of a colonial-era Pennsylvania governor and later a headquarters of George Washington

- Hope Lodge (Whitemarsh Township, Montgomery County, PA)

- Independence National Historical Park, including: Independence Hall, City Tavern, Franklin Court and Benjamin Franklin Museum, First Bank of the United States, Liberty Bell, and others) (Philadelphia, PA)

- Liberty Bell Museum (Allentown, PA), museum commemorating the hiding of the Liberty Bell inside this Allentown church for nine months during the British occupation of Philadelphia in 1777-1778

- Moland House Historic Park (aka Washington's Headquarters Farm) (Warwick Township, Bucks County, PA)

- Museum of the American Revolution (Philadelphia, PA), museum presenting the history of the American Revolution through interpretive programs, permanent exhibits, and temporary exhibits.

- Summerseat (Morrisville, Bucks County, PA), also known as the George Clymer House and Thomas Barclay House, is a historic house museum. Built about 1770, it is the only house known to have been owned by two signers of the United States Declaration of Independence, George Clymer and Robert Morris, and as a headquarters of General George Washington during the Revolutionary War.

- Thaddeus Kosciuszko National Memorial (Philadelphia, PA), historic site commemorating and interpreting the contributions of Tadeusz Kościuszko - Continental Army general and engineer.

- Valley Forge National Historical Park (Montgomery and Chester Counties, PA), National Park Service unit preserving the site and interpreting the history of the Valley Forge Encampment of the Continental Army, 1777–1778, including Washington's Headquarters.

- Washington Crossing Historic Park (Washington Crossing, Bucks County, PA), historic site and museum interpreting the crossing of the Delaware River by the Continental Army, December 25–26, 1776, for its surprise attack on Trenton.

- Fort Roberdeau (Altoona, Blair County, PA), historic site consisting of an American Revolution era fort and lead mine.

Libraries, archives, and historical societies

- American Philosophical Society, the David Library of the American Revolution transferred its extensive collection to the society, establishing the David Center for the American Revolution at the American Philosophical Society in 2020. The David Library's location in Washington Crossing, PA closed December 31, 2019.[18]

- Historical Society of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA), extensive historical archives and book holdings related to Pennsylvania history. Located on the same block as the Library Company of Philadelphia.

- Library Company of Philadelphia, library founded by Benjamin Franklin with extensive historical archives and book holdings, as well as exhibits. Located on the same block as the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Other

- Tomb of the Unknown Revolutionary War Soldier (Philadelphia, PA)

- Washington–Rochambeau Revolutionary Route (Bucks, Philadelphia, and Delaware counties, PA), National Historic Trail established in 2009 that passes through Pennsylvania, interpreting and marking the route of forces under generals George Washington and Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau during their 1781 march from Newport, Rhode Island to the site of the decisive Siege of Yorktown, Virginia.

Significant documents originating in Pennsylvania during the Revolution

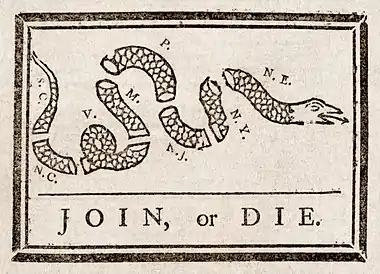

- Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania - a series of essays written by the Pennsylvania lawyer and legislator John Dickinson, leading up to the start of the Revolutionary War (1767 - 1768)

- Declaration and Resolves of the First Continental Congress (1774)

- Petition to the King - a petition sent to King George III by the First Continental Congress, calling for repeal of the Intolerable Acts (1774)

- Letters to the inhabitants of Canada (1774, 1775 and 1776)

- Olive Branch Petition - adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 5, 1775, and signed on July 8, in a final attempt to avoid a full-scale war between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies in America (1775)

- Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms (1775)

- Common Sense - pamphlet by Thomas Paine (1775-1776)

- Declaration of Independence (1776)

- Pennsylvania Constitution of 1776 (1776)

- The American Crisis - pamphlet series by Thomas Paine (1776-1777)

- Articles of Confederation - adopted by the Continental Congress at their temporary meeting location of York, PA while Philadelphia was under occupation by Crown forces (1777)

- Treaty of Fort Pitt (1778)

- An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery (1780)

- The Captivity of Benjamin Gilbert and His Family, 1780-83 - a captivity narrative by William Walton relating the experiences of a Quaker family of settlers near Mauch Chunk in present-day Carbon County, Pennsylvania. (1784)

- Pennsylvania Archives (A series of books published between 1838 and 1935 by acts of the Pennsylvania legislature - creating an official archive covering the early history of Pennsylvania, including many documents from the American Revolution - unrelated to the state agency, the Pennsylvania State Archives)

Key people

- Ann Bates - loyalist spy

- William Bradford

- Dr. Thomas Cadwalader

- Benjamin Chew

- George Clymer

- John Dickinson - Solicitor and politician, known as the "Penman of the Revolution" for his twelve Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, published individually in 1767 and 1768. Member of the First Continental Congress, signee to the Continental Association, drafted most of the 1774 Petition to the King, member of the Second Continental Congress, wrote the 1775 Olive Branch Petition. When these two attempts to negotiate with King George III of Great Britain failed, Dickinson reworked Thomas Jefferson's language and wrote the final draft of the 1775 Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms. When Congress then decided to seek independence from Great Britain, Dickinson served on the committee that wrote the Model Treaty, and then wrote the first draft of the 1776–1777 Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union. Later served as President of the 1786 Annapolis Convention, which called for the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Dickinson attended the Convention as a delegate from Delaware. He also wrote "The Liberty Song" in 1768, was a militia officer during the American Revolution, President of Delaware, President of Pennsylvania.

- Thomas Fitzsimons

- Benjamin Franklin - author, printer, political theorist, politician, scientist, inventor, humorist, civic activist, statesman, and diplomat. U.S. Ambassador to France. President of Pennsylvania. Signer of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution.

- Joseph Galloway - Delegate to the First Continental Congress, Loyalist

- Gen. Edward Hand

- Jared Ingersoll - lawyer, statesman, delegate to the Continental Congress, signer of the United States Constitution

- Brigadier General William Irvine

- Timothy Matlack

- Brigadier General Hugh Mercer

- Major General Thomas Mifflin

- William Montgomery

- Robert Morris - Signer of the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution. Superintendent of Finance of the United States. Known as the "Financier of the Revolution."

- John Morton - Delegate to the Continental Congress, signatory to the Continental Association and the Declaration of Independence. Provided the swing vote that allowed Pennsylvania to vote in favor of the Declaration of Independence. Chaired the committee that wrote the Articles of Confederation.

- Peter Muhlenberg

- Samuel Nicholas

- Joseph Reed - Delegate to the Continental Congress, signed the Articles of Confederation, President of Pennsylvania's Supreme Executive Council

- George Ross

- Dr. Benjamin Rush - Signer of the Declaration of Independence, a civic leader in Philadelphia, physician, politician, social reformer, humanitarian, educator, founder of Dickinson College

- Peggy Shippen - Spy and second wife of Major General Benedict Arnold

- James Smith

- Major General Arthur St. Clair

- Gen. Walter Stewart

- George Taylor

- Samuel Van Leer - well known local ironmaster, supplier for army during the war and officer. His Reading Furnace was used for musket repairs after the battle of Battle of Brandywine.

- Brigadier General Anthony Wayne

- Benjamin West

- Thomas Wharton Jr.

- James Wilson - Signer of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Member of the Continental Congress, and a major force in drafting the U.S. Constitution. A leading legal theorist, he was one of the six original justices appointed by George Washington to the Supreme Court of the United States.

- Sarah ("Sally") Wister - A girl living in Pennsylvania during the American Revolution who was the author of Sally Wister's Journal, a firsthand account of life in the nearby countryside during the British occupation of Philadelphia in 1777–78.

Legacy and influence: Colony to super-power

The American Revolution had wide-reaching, long-lasting impact around the world — not the least of which were the U.S. impact on republicanism internationally, numerous unilateral declarations of independence, and its eventual emergence as the world's only super-power following the Second World War and the Cold War. Unparalleled in wealth and power, the United States has remained the world's only super-power since the fall of the Soviet Union — for nearly three decades.[19][20][21]

The Revolutionary War entangled Great Britain in conflict with its rival empires of France and Spain; and also ignited open conflict between Great Britain and the United Provinces of the Netherlands (Dutch Republic).

Ultimately, the Declaration of Independence would influence many similar declarations of independence for over two-hundred years. The U.S. Declaration of Independence was considered dangerous to imperial power by some, and the Spanish-American authorities banned the circulation of the Declaration (although it was widely transmitted and translated).[22] In the Russian Empire, the full text of the Declaration of Independence was outlawed until the reign and reform era of Tsar Alexander II (1855-1881).[23]

Preservation and memorialization

Nineteen Pennsylvania counties (almost a third of its 67 counties) are named for military and political figures from the American Revolution: Adams, Armstrong, Bradford, Butler, Crawford, Fayette, Franklin, Greene, Jefferson, Luzerne, McKean, Mercer, Mifflin, Monroe, Potter, Sullivan, Warren, Washington, and Wayne counties.[24]

A convention held in Independence Hall in 1915, presided over by former US president William Howard Taft, marked the formal announcement of the formation of the League to Enforce Peace, which led to the League of Nations and eventually the United Nations. The building is part of Independence National Historical Park and has been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1979.[25]

The site of the Valley Forge winter encampment has been a National Historical Park since it was given as a gift to the nation during the U.S. bicentennial, and transferred from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to the National Park Service in 1976.

The American Battlefield Trust is working with various organizations and governments in Pennsylvania to preserve battlefields of the American Revolution, including Brandywine battlefield.[26] As of the 2010s, Chester County's government is working with the local municipalities at the sites of the Battles of Brandywine, Paoli and the Clouds, to preserve key areas in the increasingly-dense suburban communities.[27]

Many monuments and memorials exist throughout Pennsylvania dedicated to revolutionary-era figures, events, and war dead. Examples include the Tomb of the Unknown Revolutionary War Soldier in Philadelphia; the National Memorial Arch, in Valley Forge National Historical Park, Chester County — a monument built to celebrate the arrival of the Continental Army at Valley Forge; various battle monuments at Brandywine, Paoli, Wyoming, and elsewhere; and numerous statues across the state.

Several lineage societies related to the revolution currently have an organized presence in Pennsylvania, including the Society of the Descendants of Washington's Army at Valley Forge, Sons of the Revolution, Sons of the American Revolution, Daughters of the American Revolution, Children of the American Revolution, and Society of the Cincinnati.

References

- "Today in History: January 17". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 8, 2006.

- Weigley, RF et al. (eds): (1982), Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, ISBN 0-393-01610-2. page 134.

- Adams, John. "John Adams to Thomas Jefferson, 24 August 1815". National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC). National Archives of the United States. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- Continental Congress (10 November 1775). "Resolution Establishing the Continental Marines". Journal of the Continental Congress. United States Marine Corps History Division. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "Journals of the Continental Congress, 1774–1789, 8:464".

- Furgurson, Ernest B. "The British Marksman Who Refused to Shoot George Washington". HistoryNet.com. World History Group. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- Gaines, James (September 2007). "Washington & Lafayette". Smithsonian Magazine Online. Smithsonian. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- Leepson, p. 164

- Szczygielski, 1986, p. 392

- Storozynski, 2010, p. 56

- Appletons Cyclopaedia of American Biography: Pickering-Sumter, 1898, p. 133

- Kazimierz Pulaski Granted U.S. Citizenship Posthumously, 2009

- Storozynsky 2010, p. 57.

- 111th Congress Public Law 94

- Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law (United States) 111–94 (text) (PDF) U.S. Government Printing Office

- McGuire, Thomas J. (2006). Battle of Paoli. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. p. 35. ISBN 9780811733373.

- Harris, Michael C. (2014). Brandywine: A Military History of the Battle that Lost Philadelphia but Saved America, September 11, 1777. Savas Beatie LLC. p. 207. ISBN 9781611211627.

- "Introducing the David Center for the American Revolution at the American Philosophical Society". David Library of the American Revolution. Retrieved 3 August 2019.

- Bremer, Ian (May 28, 2015). "These Are the 5 Reasons Why the U.S. Remains the World's Only Superpower". Time.

- Kim Richard Nossal. Lonely Superpower or Unapologetic Hyperpower? Analyzing American Power in the post–Cold War Era. Biennial meeting, South African Political Studies Association, 29 June-2 July 1999. Archived from the original on 2019-05-26. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

- From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776 (Published 2008), by Professor George C. Herring (Professor of History at Kentucky University)

- The Contagion of Sovereignty: Declarations of Independence since 1776

- Bolkhovitinov, "The Declaration of Independence," 1393.

- "Pennsylvania Counties". Pennsylvania State Archives. Archived from the original on 2009-03-06. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Independence Hall (at "Independence Hall's History"). World Heritage Sites official webpage. World Heritage Committee. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- "Brandywine Battlefield, American Battlefield Trust". American Battlefield Trust. Retrieved 2019-07-30.

- "Battle of the Clouds Technical Report". County of Chester, Pennsylvania. County of Chester, Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

Further reading

- Fleming, Thomas. Washington's Secret War: The Hidden History of Valley Forge. 2005. ISBN 0060829621.

- Fischer, David Hackett. Washington's Crossing. 2006. ISBN 019518159X.

- Frantz, John B. and Pencak, William. Beyond Philadelphia: The American Revolution in the Pennsylvania Hinterland. 1998. ISBN 0271017678.

- Frazer, Persifor. General Persifor Frazer, A Memoir. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: no publisher listed, 1907. OCLC 51721794.

- Harris, Michael C. Brandywine: A Military History of the Battle that Lost Philadelphia but Saved America, September 11, 1777. 2014. ISBN 9781611211627.

- Knouff, Gregory T. The Soldiers' Revolution: Pennsylvanians in Arms and the Forging of Early American Identity. 2003. ISBN 027102335X.

- Lockhart, Paul. The Drillmaster of Valley Forge: The Baron de Steuben and the Making of the American Army. 2010. ISBN 0061451649.

- McGuire, Thomas J. Battle of Paoli. 2000. ISBN 0811701980.

- McGuire, Thomas J. The Philadelphia Campaign: Volume One: Brandywine and the Fall of Philadelphia. 2006. ISBN 0811701786.

- McGuire, Thomas J. The Philadelphia Campaign: Volume Two: Germantown and the Roads to Valley Forge. 2007. ISBN 0811702065.

- Nagy, John A. Spies in the Continental Capital: Espionage Across Pennsylvania During the American Revolution. 2011. ISBN 159416133X.

- Pencak, William. Pennsylvania's Revolution. 2010. ISBN 027103579X.

- Quinch, Josiah, ed. The Journals of Major Samuel Shaw. Boston, Massachusetts: Wm. Crosby and H. P. Nichols, 1847. OCLC 491802.

- Ruby, Glenn, et al., ed. Pennsylvania 1776. 1990. ISBN 027101217X.

- Seymour, Joseph. The Pennsylvania Associators, 1747-1777. Westholme Publishing. 2012. ISBN 978-1594161605.

- Linn, John Blair and Egle, William H. Pennsylvania in the War of the Revolution: Battalions and Line, 1775-1783, Volume 1. 1880. OCLC 1850676.

- Linn, John Blair and Egle, William H. Pennsylvania in the War of the Revolution: Associated Battalions and Militia, 1775-1783, Volume 2. 1880. OCLC 1850676.

External links

Bibliography

- Bibliography of the Continental Army in Pennsylvania compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History

- Bibliography of Continental Army Operations: Pennsylvania Theater compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History

- The Online Books Page: Pennsylvania - History - Revolution, 1775-1783 - Bibliography of books available online (By the University of Pennsylvania Library)

Maps