Siege of Fort Mifflin

The siege of Fort Mifflin or the siege of Mud Island Fort, which took place from September 26 to November 16, 1777, saw British land batteries commanded by Captain John Montresor and a British naval squadron under Vice Admiral Lord Richard Howe attempt to capture an American fort in the Delaware River that was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith. The operation finally succeeded after Smith was wounded. His successor, Major Simeon Thayer, subsequently evacuated the fort on the night of November 15, enabling British troops to occupy the place the following morning.

| Siege of Fort Mifflin | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Philadelphia campaign of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

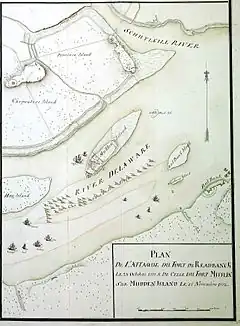

A Hessian map of Forts Mifflin and Red Bank | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,000 troops, naval squadron |

450 & reinforcements river flotilla | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

58 captured, over 62 killed HMS Augusta (64) sunk HMS Merlin (18) sunk |

250 killed and wounded entire river flotilla scuttled | ||||||

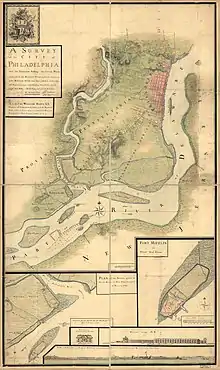

Owing to a shift of the river, Fort Mifflin is currently located on the north bank of the Delaware adjacent to Philadelphia International Airport.

After General Sir William Howe's British-Hessian army occupied Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on September 26, 1777, it became necessary to supply his troops. Fort Mifflin on Mud Island in the middle of the Delaware and Fort Mercer at Red Bank, New Jersey, together with river obstructions and a small flotilla under Commodore John Hazelwood prevented the Royal Navy from shipping provisions into the city. With Philadelphia effectively blockaded by the Americans, the Howe brothers were forced to lay siege to Fort Mifflin in order to clear the river. A Hessian attempt to storm Fort Mercer failed with heavy losses on October 22 in the Battle of Red Bank. Two British warships which had run aground near Mud Island were destroyed the next day.

General George Washington reinforced Fort Mifflin throughout the siege, but the garrison never numbered more than 500 men. After a few setbacks, the British finally assembled enough artillery and warships to bring Fort Mifflin under an intense bombardment beginning on November 10. No longer able to reply to the British bombardment, Thayer ordered the survivors to row across to New Jersey in the night and left the flag flying. Fort Mercer was abandoned soon afterward, opening the Delaware and permitting the British to hold Philadelphia until June 1778.

Background

After the British defeated the American army at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777, Howe failed to follow up Washington's withdrawal to Chester, Pennsylvania. From that town on the Delaware, the Americans marched northeast through Darby to cross the Schuylkill River at the Middle Ferry. From the ferry, the army moved north to present-day East Falls and went into camp.[1] For the next ten days, the two armies sparred while the British won the Battle of Paoli and several skirmishes. On the night of September 22, Howe outmaneuvered Washington and won an unopposed crossing of the Schuylkill near Valley Forge.[2] On September 26, the British army occupied the rebel capital of Philadelphia. In the face of the British advance the Second Continental Congress fled first to Lancaster then to York, Pennsylvania.[3]

During the summer of 1777, Philippe Charles Tronson du Coudray, a French artillery expert, arrived from France. Congress appointed him a major general and inspector general of ordnance, and Washington assigned him the task of strengthening Philadelphia's river defenses. His aristocratic airs soon irritated people. He began to quarrel with another French military engineer, Louis Lebègue Duportail, about how the defenses were to be prepared and even managed to anger Gilbert Motier, marquis de La Fayette. To the relief of many, Coudray drowned on September 16 after he foolishly rode his horse onto a Schuylkill ferry and the animal leaped into the river.[4] The Mud Island Fort was designed and begun by British engineer Captain John Montresor in 1771. The river front was shielded by a stone face, but then the work stopped due to a shortage of money. After the outbreak of war with Britain, the rest of the fort's defenses were completed with wooden palisades and earthen ramparts, despite the infighting among the French engineer officers. There were wooden barracks for the enlisted men along the west and north sides of the fort. Nearby was a two-story building to accommodate officers.[5] According to one of the defending soldiers, a battery of 18-pound artillery pieces stood at the southeast end of Mud Island. On the southwest end, one 32-pound and four or five 12-pound and 18-pound cannons guarded the river. Three 12-pound guns covered the northwest end of the island.[6] Another account states that ten 18-pound guns made up the main battery while each of the four blockhouses contained four cannons.[7] A bristling set of sharpened logs surrounded the fort while the low ground along the shoreline was infested with trous-de-loups or wolf holes. Chevaux de frise prevented the British navy from ascending the Delaware. Their iron tipped stakes threatened to tear the bottom out of any ship whose master was reckless enough to make the attempt.[6]

Siege

Preparations

Colonel Lewis Nicola held Fort Mifflin with a party of Pennsylvania militia, mostly men untrained for field service.[8] Among the approximately 60 militiamen present for duty, not a single one knew how to operate the cannons. On September 23, with Philadelphia about to be captured, Washington sent Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Smith of the 4th Maryland Regiment with a detachment of Continentals into the fort on Mud Island.[9] Smith's force numbered 200 soldiers plus Major Robert Ballard of Virginia, Major Simeon Thayer of Rhode Island, and Captain Samuel Treat[10] of the Continental Artillery.[8] However, another account stated that Thayer did not reach Fort Mifflin until October 19.[11] With the British army closing in on Philadelphia, the small force had to reach Fort Mifflin by a circuitous route. On the last leg of their journey, reinforcements for Mud Island had to be ferried across the Delaware from Red Bank, New Jersey under the protection of the Pennsylvania Navy river flotilla commanded by John Hazelwood.[8] Washington ordered Colonel the Baron Henry Leonard d'Arendt, a six-foot tall Prussian to take charge of Fort Mifflin. Since the baron was too sick to assume his post, Smith became the effective commander.[12] To further complicate matters, Lieutenant Colonel John Green of the 7th Virginia Regiment, who outranked Smith, arrived with reinforcements on October 18.[13][14] Smith developed an uneasy relationship with Hazelwood and their differences soon became obvious.[15] On October 4, Washington marched against Howe's army at the Battle of Germantown but was defeated.[3]

To deny the British the use of Province and Carpenter's Islands, the Americans broke the riverside dikes. This act forced their enemies to build their batteries on top of the dikes and to labor in knee-deep water. As an example of the difficulties involved, the British lost an 8-inch howitzer and a soldier drowned when the craft carrying the gun sank in the Schuylkill. On the night of October 10, Captain John Montresor had his crews begin work on a battery on Carpenter's Island, opposite the fort. At this time, the British already had constructed a two gun battery near the mouth of the Schuylkill River.[16] On the 11th, Hazelwood and Smith launched a joint attack by row galleys on the working parties. After losing one man killed and one wounded, a total of two officers and 56 enlisted men from the 1st Grenadier Battalion waved the white flag. The prisoners were quickly herded into the Americans' boats before engineer Captain James Moncrieffe could arrive with a rescue party of Hessians. The British court martialed two officers for this setback.[17]

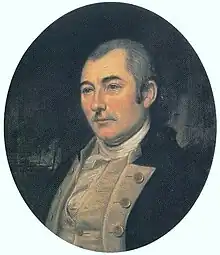

Samuel Smith in middle age. He was only 25 when he commanded Fort Mifflin |

On October 14, French engineer Major François-Louis Teissèdre de Fleury came to the fort and proved a great help to Smith.[12] Fleury, who had come to America with Du Coudray, set about improving the defenses. He built a firing step for the soldiers to fire over the palisades, a redan to support the main battery, constructed a last-stand redoubt at the fort's center, and corrected some of the fort's shortcomings.[18] Thomas Paine visited the fort on the 15th and observed that 30 enemy shells fell into the fort that day. On October 20, a British red-hot shot set off a minor explosion in the northwest blockhouse. Baron d'Arendt finally came to assume command on the 21st. While taking the Prussian on a tour of the fort, Smith and Fleury watched with shock and contempt as the terrified man ran away from the damaged blockhouse.[19] D'Arendt announced that the fort was indefensible and left Mud Island for good on October 27, pleading "illness".[20]

October 22–23

.jpg.webp)

A Hessian force under Colonel Carl von Donop attacked Fort Mercer on October 22 in the Battle of Red Bank.[21] The 1st Rhode Island Regiment under Colonel Christopher Greene had arrived at the fort only on October 11 after leaving Peekskill, New York on September 29. This was the first black unit in the Continental Army. Colonel Israel Angell's 2nd Rhode Island Regiment reached Red Bank a week later[22] and Major Thayer was sent with 150 soldiers to help garrison Fort Mifflin. When it became clear that the fort was about to be attacked, Thayer and his men recrossed the river to help in Fort Mercer's defense.[11] After Donop summoned the fort to surrender twice and each time received a negative response, he resolved to storm the place. The Rhode Islanders waited until their Hessian adversaries reached the abatis and then opened fire. The result was a one-sided slaughter. Greene's garrison lost 14 killed, 21 wounded, and one captured while inflicting 90 killed, 227 wounded, and 69 captured on their foes. The Hessians lost a high proportion of officers, including Donop who was mortally wounded.[23]

.jpg.webp)

The following day saw another stunning disaster for the British. In support of the assault on Fort Mercer, a squadron from Admiral Howe's fleet moved upriver under the command of Captain Francis Reynolds in the ship of the line HMS Augusta (64). Accompanying Augusta was the sloop HMS Merlin (18) under Commander Samuel Reeve and the frigates HMS Roebuck (44), Captain Andrew Snape Hamond, HMS Pearl (32), Captain Wilkinson, and HMS Liverpool (28), Captain Henry Bellew.[24] A force of 200 British Grenadiers waited to make an amphibious assault on Mud Island when the fort's artillery fire was suppressed.[25]

While bombarding Fort Mifflin, Augusta and Merlin went aground. High tide came that evening, but contrary winds prevented sufficient depth for the ships to be freed. On October 23, the American forts concentrated their fire on the two stricken ships. HMS Isis (50) worked its way alongside the stranded Augusta in a rescue attempt. British accounts claimed that American gunnery did only slight damage but that flaming wads from the ships' guns caused Augusta to catch fire.[24] The Americans asserted that a lucky hit from one of Fort Mifflin's red-hot shot or a fire ship started the blaze. An American soldier in the fort wrote that the fire started at the stern of Augusta and that the flames spread rapidly. At mid-day, Augusta blew up in a tremendous blast that broke windows in Philadelphia. According to Captain Montresor, 60 sailors, a lieutenant, and the ship's chaplain died while struggling in the water.[26] The loud explosion was heard nearly 30 miles (48 km) away in Trappe, Pennsylvania. After the destruction of Augusta the crew of Merlin set their ship on fire and abandoned ship. At length Merlin blew up in a less spectacular explosion.[27]

Climax

Beginning on October 26 a nor'easter struck the area and the storm lasted for three days, bringing with it high winds and torrential rain. With two feet of water over most of Mud Island and similar conditions on Province and Carpenter's Islands, the mutual cannon fire stopped as both sides tried to find a dry place.[28] By November 1, the Americans had the British army in Philadelphia effectively under blockade. Howe's troops were short of food, rum, clothing, and money. Montresor complained that he lacked adequate artillery and ammunition.[29] The British were compelled to send supplies into Philadelphia via convoys of flatboats. To avoid being sunk by the guns of Fort Mifflin and the Pennsylvania Navy, the boats had to make the attempt in the night and maintain total silence. Hessian Captain Johann von Ewald noted that in order to hold the sailors to their dangerous work, they were made completely drunk.[30]

After a council of war on October 29, Washington ordered Brigadier General James Mitchell Varnum to assume responsibility for the defense of the Delaware.[20] The two Rhode Island regiments of Varnum's brigade were already manning the forts.[31] Soon the last two units of his brigade were committed to the battle.[32] On November 3, Varnum sent the 4th and 8th Connecticut Regiments to garrison Fort Mifflin.[33]

On November 10, Montresor was finally prepared to batter down the fort. By that date he had ready for action two 32-pounder, six 24-pounder, and one 18-pounder cannon plus two 8-inch howitzers, two 8-inch mortars, and one 13-inch mortar. On the 10th, the two sides blazed away at each other at a range of 500 yards (457 m). No casualties were suffered by the Americans but large parts of the palisades on the western side of the island were wrecked.[34] On the 11th, Captain Treat was killed by the concussion of a near miss as he talked with Smith. Later that day as Smith was in the barracks, a cannonball smashed through the chimney and struck him in the left hip. Though covered in bricks from the collapsed chimney and suffering from a dislocated wrist, Smith survived because the round was spent.[35]

The wounded Smith was ferried across to Red Bank, leaving the garrison leaderless. Varnum reported that the troops would welcome a British infantry assault, but that the constant barrage was taking its toll on the men. Fleury wrote to Washington that all the guns were dismounted except two but that the soldiers of the garrison were able to repair the damage to the palisades every night. The only safe place in the fort was a ditch on the east side and Fleury would go there to round up men for work details, lashing out at the laggards with his cane.[36] The next in command after Smith was Lieutenant Colonel Giles Russell of Connecticut, but he declined and asked to be recalled. On November 12 Major Thayer accepted command of the fort.[37][38]

Sir William Howe began assembling a detachment of light infantry and Foot Guards on November 9, placing them under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Sir George Osborn, 4th Baronet. These troops were ready by the 13th and were to be supported by the 27th Foot and 29th Foot. By November 14, the British had planted two additional batteries containing four 32-pounder guns and six 24-pounder guns, which added to the furious daily bombardment.[39] That night Fort Mifflin fired on a supply convoy but missed.[40]

The British brought HMS Vigilant (20) upriver to attack the fort. Vigilant was originally the naval transport Empress of Russia. She had been converted in June 1777 into a vessel designed for shore bombardment. For this purpose, the ship carried 14 24-pounder cannon, two 9-pounders, and four 6-pounders.[41] Before the attack, the British strengthened the vessel's sides, added 24 sharpshooters and 50 gunners to the crew, and transferred two extra guns to her starboard side. To maintain the ship's stability, water casks were positioned on the port side. Lieutenant John Henry was the commanding officer.[42] Favored by a high tide, Vigilant worked its way into the shallow channel between Mud Island and the north bank at 8:00 AM on November 15. Accompanied by the sloop Fury with three 18-pounder guns, the converted transport hurled a barrage at Fort Mifflin from a distance of 20 yards (18 m).[43][44] Out in the main channel, HMS Somerset (70), Isis, Roebuck, and Pearl added the weight of their broadsides from a greater distance.[45]

Thayer ordered his 32-pounder cannon to be moved to the place of danger. Before Vigilant reached her station, the gun crew claimed to have fired 14 shots into her. After the floating battery came to anchor, the fort was subjected to a terrific point blank fire. A single shot killed five American gunners at one cannon. A defender wrote that men were, "split like fish to be broiled".[46] Thayer ordered a distress signal to be hoisted requesting help from Hazelwood, but to do so the fort's flag had to be lowered first. When the British gunners ceased fire and began to cheer in anticipation of victory, Thayer's officers demanded that the flag be immediately raised again. The bombardment resumed and the artillery sergeant detailed to haul the flag was the next casualty, cut in half by a cannonball. That afternoon, a chunk of wood from the smashed barracks struck down artillery Captain James Lee and knocked Fleury unconscious. When Hazelwood's ships tried to attack Vigilant and Fury, fire from the British naval squadron drove them back. By this time the interior of the fort was furrowed with the tracks of cannonballs and the barracks and blockhouses were wrecked.[47][48]

Osborn planned to send eight flatboats each with 35 soldiers in the first wave of his assault. Howe declined to give the order for the 400-man storming party to attack, waiting for a high tide and hoping that the garrison would evacuate the fort. That evening at around 11:30 PM, Thayer gave the order to abandon Fort Mifflin.[49] The 300 survivors and what equipment could be salvaged were rowed across to Red Bank. Thayer held back a detail of 40 men. These troops burned down the barracks at midnight and soon joined the others in New Jersey. Thayer was the last one to leave.[50]

Result

At 6:00 AM on the morning of November 16, HMS Vigilant launched a boat manned by British marines to haul down the American flag, which had been left flying. Two hours later, Osborn's troops landed amid snow flurries and took possession of the ruined fort. They were greeted by a lone American deserter who told them that Thayer's men suffered about 50 killed and 70 to 80 wounded.[51] Historian Mark M. Boatner III estimated total American casualties at 250 killed and wounded[7] from a garrison that counted 450 men plus reinforcements.[52] British losses in the last phase of the siege were seven killed and five wounded, nearly all of them were crewman on the Vigiliant.[21] The victors were appalled at the damage and at the blood and brains strewn about the fort's interior. While the needy enlisted men were busy looting the corpses for shoes and clothing, a few of the British officers admitted in their letters that the defenders had been brave.[53]

On November 17, Lieutenant General Lord Charles Cornwallis crossed the river with 2,000 men to prepare for an assault on Fort Mercer. In the face of this threat, Colonel Greene evacuated Fort Mercer and Cornwallis seized the place unopposed on November 20.[21] With the forts gone, Hazelwood set his ships on fire that night to prevent their capture by the British.[54] The Delaware was now open to the Royal Navy and the army of occupation in Philadelphia could be supplied.[21] The next action occurred at the Battle of Gloucester on November 25 as Cornwallis withdrew from New Jersey.[55]

See also

Notes

- McGuire, 273

- McGuire, 320–322

- Dupuy & Dupuy, 715

- McGuire, 282

- McGuire, 182

- McGuire, 183

- Boatner, 384

- McGuire, 184

- McGuire, 137

- Sec. of Commonwealth, 37

- Thayer & Stone, 75

- McGuire, 185

- McGuire, 186

- Dorwart, 38

- McGuire, 184–186

- McGuire, 186–187

- McGuire, 187–190

- Dorwart, 37–38

- McGuire, 191

- Dorwart, 42

- Eggenberger, 149

- McGuire, 138–139

- McGuire, 161–166

- Phillips, Augusta

- McGuire, 172

- McGuire, 173

- McGuire, 174

- McGuire, 194

- McGuire, 180

- McGuire, 152–153

- McGuire, 151

- IHA, Valley Forge. Varnum's Brigade comprised the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island and the 4th and 8th Connecticut.

- McGuire, 197

- McGuire, 195–197

- McGuire, 198

- McGuire, 199–200

- Thayer & Stone, 76

- Heitman (1914), 477. This source gives Russell's full name and regiment (8th Connecticut).

- McGuire, 200–201

- McGuire, 202

- Syrett (1978), 57–58

- Syrett (1978), 58–59

- McGuire, 201–203

- Thayer & Stone, 76–77

- McGuire, 205

- McGuire, 204–205

- McGuire, 206–207. According to McGuire's source, Lee was killed.

- Heitman (1914), 345. This authority stated that Lee resigned from the army on 11 December 1779.

- McGuire, 207–208

- Thayer & Stone, 77

- McGuire, 209–210

- Boatner, 383

- McGuire, 210–211

- McGuire, 219

- McGuire, 221

References

- Boatner, Mark M. III (1994). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, Pa.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1.

- Dorwart, Jeffrey M. (1998). Fort Mifflin of Philadelphia. Philadelphia, Pa.: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-3430-8.

- Dupuy, R. Ernest; Dupuy, Trevor N. (1977). The Encyclopedia of Military History. New York, N.Y.: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-011139-9.

- Eggenberger, David (1985). An Encyclopedia of Battles. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-24913-1.

- Heitman, Francis Bernard (1914). Historical Register of Officers of the Continental Army during the War of the Revolution. Washington, D.C.: Rare Book Shop Publishing Company.

Jackson, John, Fort Mifflin: Valiant Defender of the Delaware James & Sons, Norristown, PA; 1986, 206 pages

Jackson, John, The Pennsylvania Navy, 1775-1781 Rutgers University Press

Martin, Joseph Plum, Private Yankee Doodle Western Acorn Press, 1962

- McGuire, Thomas J. (2007). The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume II. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0206-5.

- Phillips, Michael. "AUGUSTA (64) 4th Rate". ageofnelson.org. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- "Regiments at Valley Forge". Independence Hall Association (IHA). Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Syrett, David (February 1978). "H.M. Armed Ship Vigilant". Mariner's Mirror. London: Society for Nautical Research. 64 (1): 57–62. doi:10.1080/00253359.1978.10659065. ISSN 0025-3359.

- Thayer, Simeon (1867). Stone, Edwin Martin (ed.). The Invasion of Canada in 1775: Including the Journal of Captain Simeon Thayer, Describing the Perils and Sufferings of the Army Under Colonel Benedict Arnold, in Its March Through the Wilderness to Quebec. Providence, R.I.: Rhode Island Historical Society.

- Massachusetts, Secretary of the Commonwealth (1907). Massachusetts Soldiers and Sailors in the War of the Revolution. Boston, MA.: Boston, Wright and Potter Printing Co., Sate Printers.