Amphiaraus

In Greek mythology, Amphiaraus or Amphiaraos (/ˌæmfiəˈreɪəs/; Ancient Greek: Ἀμφιάραος, Ἀμφιάρεως, "very sacred"[1]) was the son of Oicles, a seer, and one of the leaders of the Seven against Thebes. Amphiaraus at first refused to go with Adrastus on this expedition against Thebes as he foresaw the death of everyone who joined the expedition. His wife, Eriphyle, eventually compelled him to go.[2]

Family

Amphiaraus was the son of Oicles.[3] This made Amphiaraus a great-grandson of Melampus, himself a legendary seer,[4] and a member of one of the most powerful dynastic families in the Argolid.[5] The mythographer Hyginus says that Amphiaraus's mother was Hypermnestra, the daughter of Thestius.[6] She was the sister of Leda, the queen of Sparta who was the mother of Helen of Troy, Clytemnestra, and the Dioscuri (Castor and Pollux).[7] Hyginus also reports that "some authors" said that Amphiaraus was the son of Apollo.[8]

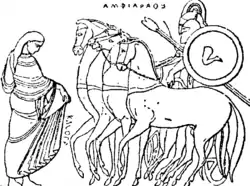

Amphiaraus married Eriphyle, the sister of his cousin Adrastus (the grandson of Melampus' brother Bias), and by her was the father of two sons, Alcmaeon and Amphilochus.[9] From the geographer Pausanias, we hear of three daughters, Eurydice, Demonissa and Alcmena. He reports seeing on the Chest of Kypselos at Olympia, a scene showing Amphiararaus' departure for the expedition against Thebes. Pausanias identifies (possible from inscriptions) other participants in the scene as: the infant Amphilochus, Eryphyle, her daughters, Eurydice and Demonissa, and a naked Alcmaeon.[10] He goes on to add that the poet Asius also has Alcmena as a daughter of Amphiaraus and Eriphyle.[11] According to Plutarch, Alexida was a daughter of Amphiaraus.[12]

The Clytidae (alternate spelling "Klytidiai"), a clan of seers at Olympia, claimed to be the descendants of a Clytius, who they said was the son of Amphiaraus' son Alcmaeon.[13] According to Roman legends, the founder of the town of Tibur (modern Tivoli) near Rome, was a son of Amphiaraus.[14]

Mythology

Amphiaraus was a seer, and greatly honored in his time. Both Zeus and Apollo favored him, and Zeus gave him his oracular talent. In the generation before the Trojan War, Amphiaraus was one of the heroes present at the Calydonian boar hunt.[15]

The material of the tragic war of the Seven against Thebes was taken up from several points of view by each of the three great Greek tragic poets. Eriphyle persuaded Amphiaraus to take part in the raiding venture, against his better judgment, for he knew he would die.[16] She had been persuaded by Polynices, who offered her the necklace of Harmonia, daughter of Aphrodite, once part of the bride-price of Cadmus, as a bribe for her advocacy. Amphiaraus reluctantly agreed to join the doomed undertaking, but aware of his wife's corruption, asked his sons, Alcmaeon and Amphilochus, to avenge his inevitable death by killing her, should he not return. He had foreseen the failure and for this reason did not agree to join first.[17] On the way to the battle, Amphiaraus repeatedly warned the other warriors that the expedition would fail,[18] and blamed Tydeus for starting it. For this, he would eventually prevent the dying Tydeus from being immortalized by Athena, by giving him the still-living severed head of his foe Melanippus, whose brains Tydeus devoured along with his last breath, revolting the goddess. (This scene, as rendered by Statius, provided the model for Dante's own seminal account of Ugolino gnawing on Ruggieri's skull in Cantos XXXII and XXXIII of the Inferno.) At some point, while the allies of Polyneices sat down to feast, an eagle swooped down and grabbed Amphiaraus's spear, taking it to a great height and then letting it drop on the earth. The spear was fixed in the soil, and transformed into a laurel tree.[19]

In the battle, Amphiaraus sought to flee from Periclymenus, the "very famous"[20] son of Poseidon, who wanted to kill him, but Zeus threw his thunderbolt, and the earth opened to swallow and conceal Amphiaraus, right on the same spot the laurel had grown from his spear,[19] and his chariot before Periclymenus could stab him in the back and thereby disgrace his honor.[21] Thus becoming a chthonic hero, Amphiaraus was later propitiated and consulted at his sanctuary.

Legacy

Alcmaeon killed his mother when Amphiaraus died. He was pursued by the Erinyes as he fled across Greece, eventually landing at the court of King Phegeus, who gave him his daughter Alphesiboea in marriage. Exhausted, Alcmaeon asked an oracle how to avoid the Erinyes and was told that he needed to stop where the sun was not shining when he killed his mother. That was the mouth of the river Achelous, which had been silted up. Achelous himself, god of that river, promised him his daughter, Callirrhoe in marriage if Alcmaeon would retrieve the necklace and clothes which Eriphyle wore when she persuaded Amphiaraus to take part in the battle. Alcmaeon had given these jewels to Phegeus who had his sons kill Alcmaeon when he discovered Alcmaeon's plan.

In a sanctuary at the Amphiareion of Oropos, northwest of Attica, Amphiaraus was worshipped with a hero cult. He was considered a healing and fortune-telling god and was associated with Asclepius. The healing and fortune-telling aspect of Amphiaraus came from his ancestry: he descended from the great seer Melampus. After making a sacrifice of a few coins, or sometimes a ram, at the temple, a petitioner slept inside[22] and received a dream detailing the solution to the problem.

Amphiaraia (ἀμφιαράϊα), were games celebrated in honour of Amphiaraus in Oropus.[23]

Etruscan tradition inherited by the Romans is doubtless the origin of a son for Amphiaraus named Catillus who escaped from the slaughter at Thebes and led an expedition to Italy, where he founded a colony where eventually appeared the city of Tibur (now Tivoli), named after his eldest son Tiburtus.

Philosophy

| Part of a series on |

| Pyrrhonism |

|---|

|

|

|

In the Python, the first book to describe Pyrrhonist philosophy, the book's author, Timon of Phlius first meets Pyrrho on the grounds of the temple of Amphiaraus. The symbolism of this may be due to Pyrrho being a member of the Clytidae, a clan of seers in Elis who interpreted the oracles of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. The founder of the clan was claimed to be Clytius, the grandson of Amphiaraus.[24]

Popular culture

- In March 1815 Franz Schubert set "Amphiaraos," a poem by Theodor Körner, as a lied for voice and piano, D 166.[25] It was first published in the Franz Schubert's Works edition in 1894.[26] The New Schubert Edition included the song in Series IV, Volume 8.[27]

- In Dante Alighieri's Inferno, King Amphiaraus was seen in the Sorcerers' section of Hell's Circle of Fraud where his action of foreseeing his death is mentioned.

Notes

- Oxford Classical Dictionary s.v. Amphiaraus.

- Oxford Classical Dictionary s.v. Amphiaraus; Parada, s.v. Amphiaraus.

- Parada, s.v. Amphiaraus; Hyginus, Fabulae 70, 73. Amphiaraus as the son of Oicles is attested as early as Homer, Odyssey, 15.243, see also Bacchylides, 9.10–24; Pindar, Pindar, Nemean, 9.13–17, 10.7–9 , Olympian 6.13–17, Pythian 8.39–55; Apollodorus, 3.6.3. For genealogical tables showing Amphiaraus and other of the descendants of Melampus, see Hard, p. 706, Table 13, and Grimal, p. 525, Table I.

- The descendants of Melampus included many notable seers, the most notable, after Melampus and Amphiaraus, being the Corinthian seer Polyidus; for a discussion see Hard, pp. 429–430.

- For a discussion of the dynastic history of the Argolid, see Hard, pp. 332–335.

- Hyginus, Fabulae 70.

- For Hypermnestra, see Hard, p. 413.

- Hyginus, Fabulae 70. As H. J. Rose, Oxford Classical Dictionary s.v. Amphiaraus, points out, a seer being said to have been the son of Apollo was not uncommon, see e.g. Aristaeus, Iamus, and Idmon.

- Apollodorus, 1.9.13, 3.6.2 (Eriphyle as wife), 3.7.2 (father of Alcmaeon and Amphilochus). Eriphyle as Amphiaraus' wife is alluded to by Homer, Odyssey 11.326–327 ("hateful Eriphyle, who took precious gold as the price of the life of her own lord"), 15.246–247 ("Amphiaraus" [who died at Thebes] "because of a woman's gifts"). For Eriphyle as wife, see also Pindar, Nemean 9.16–17; Diodorus Siculus, 4.65.6. For Alcmaeon as son see also Pausanias 6.17.6.

- Gantz, p. 508; Frazer, pp. 608–610; Pausanias, 5.17.7.

- Pausanias, 5.17.8 [= Asius fr. 4 West.

- Plutarch, Quaestiones Graecae 23.

- Hard, p. 430; Pausanias, 6.17.6.

- Smith 1854, s.v. Tibur; Smith 1873, s.v. Amphiaraus; Grimal, s.v. Amphiaraus; Gaius Julius Solinus, Polyhistor 2.8–9; Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 16.87. Solinus, reports that, according to Cato, "Catillus the Arcadian", an officer of Evander, was the founder of Tibur, and Solinus goes on to say that this Catillus was the son of Amphiaraus, and that, on his grandfather Oicles' orders, he migrated to Italy, had three sons Tibertus, Coras and Catillus, expelled the Sicilia from the town of Sicani, and renamed the town Tibur after his eldest son Tibertus. Pliny the Elder, says that the founder of Tivoli was Amphiaraus' son Tiburnus. See also Virgil, Aeneid 7.670–672, Horace, Odes 1.18.2, 2.6.5.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 1.8.2: "Atalanta was the first to shoot the boar in the back with an arrow, and Amphiaraus was the next to shoot it in the eye; but Meleager killed it by a stab in the flank...".

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.8.2

- Roman, L., & Roman, M. (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman mythology., p. 57, at Google Books

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.6.2

- Plutarch, Parallel Lives 6

- Karl Kerenyi (The Heroes of the Greeks, 1959, p. 300) noted that the name would also be a suitable epithet for Hades.

- Pindar, Nemean Odes 9

- See Incubation (ritual).

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities (1890), Amphiaraia

- Dee L. Clayman, Timon of Phlius: Pyrrhonism into Poetry ISBN 3110220806 2009 p51

- Amphiaraos at The LiederNet Archive

- Otto Erich Deutsch. Schubert Thematic Catalogue. 1978. p. 118

- Lieder, Band 8 at www

.baerenreiter .com

References

- Apollodorus, The Library with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. ISBN 0-674-99135-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library. Greek text available from the same website.

- Apps, Arwen Elizabeth, Gaius Iulius Solinus and His Polyhistor, Macquarie University (PhD dissertation), 2011.

- Bacchylides, Odes, translated by Diane Arnson Svarlien. 1991. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Twelve volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989. Online version by Bill Thayer.

- Frazer, J. G., Pausanias's Description of Greece. Translated with a Commentary by J. G. Frazer. Vol III. Commentary on Books II-V, Macmillan, 1898. Internet Archive.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Grimal, Pierre, The Dictionary of Classical Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 978-0-631-20102-1.

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360. Google Books.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Odyssey with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, PH.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1919. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Horace. Odes and Epodes. Edited and translated by Niall Rudd. Loeb Classical Library No. 33. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2004. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Fabulae in Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology, Translated, with Introductions by R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma, Hackett Publishing Company, 2007. ISBN 978-0-87220-821-6.

- The Oxford Classical Dictionary, second edition, Hammond, N.G.L. and Howard Hayes Scullard (editors), Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-869117-3.

- Parada, Carlos, Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology, Jonsered, Paul Åströms Förlag, 1993. ISBN 978-91-7081-062-6.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece with an English Translation by W.H.S. Jones, Litt.D., and H.A. Ormerod, M.A., in 4 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1918. ISBN 0-674-99328-4. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library

- Pausanias, Graeciae Descriptio. 3 vols. Leipzig, Teubner. 1903. Greek text available at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plutarch, Moralia, Volume IV: Roman Questions. Greek Questions. Greek and Roman Parallel Stories. On the Fortune of the Romans. On the Fortune or the Virtue of Alexander. Were the Athenians More Famous in War or in Wisdom?. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. Loeb Classical Library 305. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1936.

- Plutarch, Quaestiones Graecae in Moralia, Volume IV: Roman Questions. Greek Questions. Greek and Roman Parallel Stories. On the Fortune of the Romans. On the Fortune or the Virtue of Alexander. Were the Athenians More Famous in War or in Wisdom?. Translated by Frank Cole Babbitt. Loeb Classical Library No. 305. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1936. ISBN 978-0-674-99336-5. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Race, William H. (1997a), Pindar: Nemean Odes. Isthmian Odes. Fragments, Edited and translated by William H. Race. Loeb Classical Library No. 485. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-674-99534-5. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Race, William H. (1997b), Pindar: Olympian Odes. Pythian Odes. Edited and translated by William H. Race. Loeb Classical Library No. 56. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0-674-99564-2. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Smith, William (1854), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography, London (1854). Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Smith, William (1873), Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873). Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Virgil, Aeneid [books 7–12], in Aeneid: Books 7-12. Appendix Vergiliana, translated by H. Rushton Fairclough, revised by G. P. Goold, Loeb Classical Library No. 64, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-674-99586-4. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- West, M. L., Greek Epic Fragments: From the Seventh to the Fifth Centuries BC, edited and translated by Martin L. West, Loeb Classical Library No. 497, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-674-99605-2. Online version at Harvard University Press.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)