Myrrha

Myrrha (Greek: Μύρρα, Mýrra), also known as Smyrna (Greek: Σμύρνα, Smýrna), is the mother of Adonis in Greek mythology. She was transformed into a myrrh tree after having intercourse with her father, and gave birth to Adonis in tree form. Although the tale of Adonis has Semitic roots, it is uncertain where the myth of Myrrha emerged from, though it was probably from Cyprus.

The myth details the incestuous relationship between Myrrha and her father, Cinyras. Myrrha falls in love with her father and tricks him into sexual intercourse. After discovering her identity, Cinyras draws his sword and pursues Myrrha. She flees across Arabia and, after nine months, turns to the gods for help. They take pity on her and transform her into a myrrh tree. While in plant form, Myrrha gives birth to Adonis. According to legend, the aromatic exudings of the myrrh tree are Myrrha's tears.

The most familiar form of the myth was recounted in the Metamorphoses of Ovid, and the story was the subject of the most famous work (now lost) of the poet Helvius Cinna. Several alternate versions appeared in the Bibliotheca, the Fabulae of Hyginus, and the Metamorphoses of Antoninus Liberalis, with major variations depicting Myrrha's father as the Assyrian king Theias or depicting Aphrodite as having engineered the tragic liaison. Critical interpretation of the myth has considered Myrrha's refusal of conventional sexual relations to have provoked her incest, with the ensuing transformation to tree as a silencing punishment. It has been suggested that the taboo of incest marks the difference between culture and nature and that Ovid's version of Myrrha showed this. A translation of Ovid's Myrrha, by English poet John Dryden in 1700, has been interpreted as a metaphor for British politics of the time, linking Myrrha to Mary II and Cinyras to James II.

In post-classical times, Myrrha has had widespread influence in Western culture. She was mentioned in the Divine Comedy by Dante, was an inspiration for Mirra by Vittorio Alfieri, and was alluded to in Mathilda by Mary Shelley. In the play Sardanapalus by Byron, a character named Myrrha appeared, whom critics interpreted as a symbol of Byron's dream of romantic love. The myth of Myrrha was one of 24 tales retold in Tales from Ovid by English poet Ted Hughes. In art, Myrrha's seduction of her father has been illustrated by German engraver Virgil Solis, her tree-metamorphosis by French engraver Bernard Picart and Italian painter Marcantonio Franceschini, while French engraver Gustave Doré chose to depict Myrrha in Hell as a part of his series of engravings for Dante's Divine Comedy. In music, she has appeared in pieces by Sousa and Ravel. She was also the inspiration for several species' scientific names and an asteroid.

Origin and etymology

The myth of Myrrha is closely linked to that of her son, Adonis, which has been easier to trace. Adonis is the Hellenized form of the Phoenician word "adoni", meaning "my lord".[1] It is believed that the cult of Adonis was known to the Greeks from around the sixth century B.C., but it is unquestionable that they became aware of it through contact with Cyprus.[1] Around this time, the cult of Adonis is noted in the Book of Ezekiel in Jerusalem, though under the Babylonian name Tammuz.[1][2]

Adonis originally was a Phoenician god of fertility representing the spirit of vegetation. It is further speculated that he was an avatar of the version of Ba'al, worshipped in Ugarit. It is likely that lack of clarity concerning whether Myrrha was called Smyrna, and who her father was, originated in Cyprus before the Greeks first encountered the myth. However, it is clear that the Greeks added much to the Adonis-Myrrha story, before it was first recorded by classical scholars.[1]

Over the centuries Myrrha, the girl, and myrrh, the fragrance, have been linked etymologically. Myrrh was precious in the ancient world, and was used for embalming, medicine, perfume, and incense. The Modern English word myrrh (Old English: myrra) derives from the Latin Myrrha (or murrha or murra, all are synonymous Latin words for the tree substance).[3] The Latin Myrrha originated from the Ancient Greek múrrā, but, ultimately, the word is of Semitic origin, with roots in the Arabic murr, the Hebrew mōr, and the Aramaic mūrā, all meaning "bitter"[4] as well as referring to the plant.[5][6] Regarding smyrna, the word is a Greek dialectic form of myrrha.[7]

In the Bible, myrrh is referenced as one of the most desirable fragrances, and though mentioned alongside frankincense, it is usually more expensive.[8][lower-alpha 1] Several Old Testament passages refer to myrrh. In the Song of Solomon, which according to scholars dates to either the tenth century B.C. as a Hebrew oral tradition[10] or to the Babylonian captivity in the 6th century B.C.,[11] myrrh is referenced seven times, making the Song of Solomon the passage in the Old Testament referring to myrrh the most, often with erotic overtones.[8][12][13] In the New Testament the substance is famously associated with the birth of Christ when the magi presented their gifts of "gold, frankincense, and myrrh".[14][lower-alpha 2]

Myth

Ovid's version

Published in 8 A.D. the Metamorphoses of Ovid has become one of the most influential poems by writers in Latin.[15][16] The Metamorphoses show that Ovid was more interested in questioning how laws interfered with people's lives than writing epic tales like Virgil's Aeneid or Homer's Odyssey.[15] The Metamorphoses is not narrated by Ovid,[lower-alpha 3] but rather by the characters in the stories.[15] The myth of Myrrha and Cinyras is sung by Orpheus in the tenth book of Metamorphoses after he has told the myth of Pygmalion[lower-alpha 4] and before he turns to the tale of Venus and Adonis.[19] As the myth of Myrrha is also the longest tale sung by Orpheus (205 lines) and the only story that corresponds to his announced theme of girls punished for forbidden desire, it is considered the centerpiece of the song.[20] Ovid opens the myth with a warning to the audience that this is a myth of great horror, especially to fathers and daughters:

The story I am going to tell is a horrible one: I beg that daughters and fathers should hold themselves aloof, while I sing, or if they find my songs enchanting, let them refuse to believe this part of my tale, and suppose that it never happened: or else, if they believe that it did happen, they must believe also in the punishment that followed.[21]

According to Ovid, Myrrha was the daughter of King Cinyras and Queen Cenchreis of Cyprus. Ovid says that Cupid was not to blame for Myrrha's incestuous love for her father, Cinyras; he comments that hating one's father is a crime, but that Myrrha's love was a greater crime,[22] and blames it instead on the Furies.[23]

Over several verses, Ovid depicts the psychic struggle Myrrha faces between her sexual desire for her father and the social shame she would face for acting on it.[23] Sleepless, and losing all hope, she attempts suicide; but is discovered by her nurse, in whom she confides. The nurse tries to make Myrrha suppress the infatuation, but later agrees to help Myrrha into her father's bed if she promises that she will not try to kill herself again.[23]

During the Ceres' festival, the worshipping women (including Cenchreis, Myrrha's mother) were not to be touched by men for nine nights; the nurse tells Cinyras of a girl deeply in love with him, giving a false name. The affair lasts several nights in complete darkness to conceal Myrrha's identity,[lower-alpha 5] until Cinyras wanted to know the identity of his paramour. Upon bringing in a lamp, and seeing his daughter, the king attempted to kill her on the spot, but Myrrha escaped.[23]

Thereafter Myrrha walked in exile for nine months, past the palms of Arabia and the fields of Panchaea, until she reached Sabaea.[lower-alpha 6] Afraid of death and tired of life, and pregnant as well, she begged the gods for a solution, and was transformed into the myrrh tree, with the sap thereof representing her tears. Later, Lucina freed the newborn Adonis from the tree.[23]

Other versions

The myth of Myrrha has been chronicled in several other works than Ovid's Metamorphoses. Among the scholars who recounted it are Apollodorus, Hyginus, and Antoninus Liberalis. All three versions differ.

In his Bibliotheca, written around the 1st century B.C. Apollodorus[lower-alpha 7] tells of three possible parentages for Adonis. In the first he states that Cinyras arrived in Cyprus with a few followers and founded Paphos, and that he married Metharme, eventually becoming king of Cyprus through her family. Cinyras had five children by Metharme: the two boys, Oxyporos and Adonis, and three daughters, Orsedice, Laogore, and Braisia. The daughters at some point became victims of Aphrodite's wrath and had intercourse with foreigners,[lower-alpha 8] ultimately dying in Egypt.[26]

For the second possible parentage of Adonis, Apollodorus quotes Hesiod, who postulates that Adonis could be the child of Phoenix and Alphesiboia. He elaborates no further on this statement.[27]

For the third option, he quotes Panyasis, who states that King Theias of Assyria had a daughter called Smyrna. Smyrna failed to honor Aphrodite, incurring the wrath of the goddess, by whom was made to fall in love with her father; and with the aid of her nurse she deceived him for twelve nights until her identity was discovered. Smyrna fled, but her father later caught up with her. Smyrna then prayed that the gods would make her invisible, prompting them to turn her into a tree, which was named the Smyrna. Ten months later the tree cracked and Adonis was born from it.[27]

In his Fabulae, written around 1 A.D. Hyginus states that King Cinyras of Assyria had a daughter by his wife, Cenchreis. The daughter was named Smyrna and the mother boasted that her child excelled even Venus in beauty. Angered, Venus punished the mother by cursing Smyrna to fall in love with her father. After the nurse had prevented Smyrna from committing suicide, she helped her engage her father in sexual intercourse. When Smyrna became pregnant, she hid in the woods from shame. Venus pitied the girl's fate, changing her into a myrrh tree, from which was born Adonis.[28]

In the Metamorphoses by Antoninus Liberalis, written somewhere in the 2nd or 3rd century A.D.,[29][lower-alpha 9] the myth is set in Phoenicia, near Mount Lebanon. Here King Thias, son of Belus and Orithyia,[lower-alpha 10] had a daughter named Smyrna. Being of great beauty, she was sought by men from far and wide. She had devised many tricks in order to delay her parents and defer the day they would choose a husband for her. Smyrna had been driven mad[lower-alpha 11] by desire for her father and did not want anybody else. At first she hid her desires, eventually telling her nurse, Hippolyte,[lower-alpha 12] the secret of her true feelings. Hippolyte told the king that a girl of exalted parentage wanted to lie with him, but in secret. The affair lasted for an extended period of time, and Smyrna became pregnant. At this point, Thias desired to know who she was so he hid a light, illuminating the room and discovering Smyrna's identity when she entered. In shock, Smyrna gave birth prematurely to her child. She then raised her hands and said a prayer, which was heard by Zeus who took pity on her and turned her into a tree. Thias killed himself,[lower-alpha 13] and it was on the wish of Zeus that the child was brought up and named Adonis.[31]

In a rare version, Myrrha's curse was inflicted on her by Helios, the sun god, over some unclear insult,[33] which might reflect the role the Sun has in the myrrh's production, but nevertheless this version was far from being a popular one.[34]

Interpretation

The myth of Myrrha has been interpreted in various ways. The transformation of Myrrha in Ovid's version has been interpreted as a punishment for her breaking the social rules through her incestuous relationship with her father. Like Byblis who fell in love with her brother, Myrrha is transformed and rendered voiceless making her unable to break the taboo of incest.[35]

Myrrha has also been thematically linked to the story of Lot's daughters. They live with their father in an isolated cave and because their mother is dead they decide to befuddle Lot's mind with wine and seduce him in order to keep the family alive through him.[36][37] Nancy Miller comments on the two myths:

[Lot's daughters'] incest is sanctioned by reproductive necessity; because it lacks consequences, this story is not a socially recognized narrative paradigm for incest. [...] In the cases of both Lot's daughters and Myrrha, the daughter's seduction of the father has to be covert. While other incest configurations - mother-son, sibling - permit consensual agency, father-daughter incest does not; when the daughter displays transgressive sexual desire, the prohibitive father appears.[37]

Myrrha has been interpreted as developing from a girl into a woman in the course of the story: in the beginning she is a virgin refusing her suitors, in that way denying the part of herself that is normally dedicated to Aphrodite. The goddess then strikes her with desire to make love with her father and Myrrha is then made into a woman in the grip of an uncontrollable lust. The marriage between her father and mother is then set as an obstacle for her love along with incest being forbidden by the laws, profane as well as divine. The way the daughter seduces her father illustrates the most extreme version a seduction can take: the union between two persons who by social norms and laws are strictly held apart.[38]

James Richard Ellis has argued that the incest taboo is fundamental to a civilized society. Building on Sigmund Freud's theories and psychoanalysis this is shown in Ovid's version of the myth of Myrrha. When the girl has been gripped by desire, she laments her humanity, for if she and her father were animals, there would be no bar to their union.[39]

That Myrrha is transformed into a myrrh tree has also been interpreted to have influenced the character of Adonis. Being the child of both a woman and a tree he is a split person. In Ancient Greece the word Adonis could mean both "perfume" and "lover"[lower-alpha 14] and likewise Adonis is both the perfume made from the aromatic drops of myrrh as well as the human lover who seduces two goddesses.[38]

In her essay "What Nature Allows the Jealous Laws Forbid" literary critic Mary Aswell Doll compares the love between the two male protagonists of Annie Proulx' book Brokeback Mountain (1997) with the love Myrrha has for her father in Ovid's Metamorphoses. Doll suggests that both Ovid's and Proulx' main concerns are civilization and its discontents and that their use of images of nature uncovers similar understandings of what is "natural" when it comes to who and how one should love. On the subject of Ovid’s writing about love Doll states:

In Ovid’s work no love is "taboo" unless it arises out of a need for power and control. A widespread instance for the latter during the Roman Empire was the practice by the elite to take nubile young girls as lovers or mistresses, girls who could be as young as daughters. Such a practice was considered normal, natural.[15]

Cinyras' relationship with a girl on his daughter's age was therefore not unnatural, but Myrrha's being in love with her own father was. Doll elaborates further on this stating that Myrrha's lamenting that animals can mate father and daughter without problems is a way for Ovid to express a paradox: in nature a father-daughter relationship is not unnatural, but it is in human society. On this Doll concludes that "Nature follows no laws. There is no such thing as "natural law"".[15] Still, Ovid distances himself in three steps from the horrifying story:

First he does not tell the story himself, but has one of his in-story characters, Orpheus, sing it;[41] second, Ovid tells his audience not even to believe the story (cf. quote in "Ovid's version");[21] third, he has Orpheus congratulate Rome, Ovid's home town, for its being far away from the land where this story took place (Cyprus).[42] By distancing himself, Doll writes, Ovid lures his audience to keep listening. First then does Ovid begin telling the story describing Myrrha, her father and their relationship, which Doll compares to the mating of Cupid and Psyche:[lower-alpha 15] here the lovemaking occurs in complete darkness and only the initiator (Cupid) knows the identity of the other as well. Myrrha's metamorphosing into a tree is read by Doll as a metaphor where the tree incarnates the secret. As a side effect, Doll notes, the metamorphosis also alters the idea of incest into something natural for the imagination to think about. Commenting on a Freudian analysis of the myth stating that Ovid "disconcertingly suggests that [father-lust] might be an unspoken universal of human experience".[43] Doll notes that Ovid's stories work like metaphors: they are meant to give insight into the human psyche. Doll states that the moments when people experience moments like those of father-lust are repressed and unconscious, which means that they are a natural part of growing and that most grow out of it sometime. She concludes about Ovid and his version of Myrrha that: "What is perverted, for Ovid, is the use of sex as a power tool and the blind acceptance of sexual male power as a cultural norm."[15]

In 2008 the newspaper The Guardian named Myrrha's relationship with her father as depicted in Metamorphoses by Ovid as one of the top ten stories of incestuous love ever. It complimented the myth for being more disturbing than any of the other incestuous relationships depicted in the Metamorphoses.[44]

Particularly in light of the themes of secrecy in the taboo, and the patriarchal nature of Ovid's society, the myth may also serve to reverse the narrative on cases where the father manipulates and sexually abuses his own daughters and no actual seduction of the father by the daughter occurs, except in his own mind. This would be similar to how The Freudian Coverup theory functions socially.

Cultural impact

Literature

One of the earliest recordings of a play inspired by the myth of Myrrha is in the Antiquities of the Jews, written in 93 A.D. by the Roman-Jewish historian Flavius Josephus.[45] A tragedy entitled Cinyras is mentioned, wherein the main character, Cinyras, is to be slain along with his daughter Myrrha, and "a great deal of fictitious blood was shed".[46] No further details are given about the plot of this play.[46]

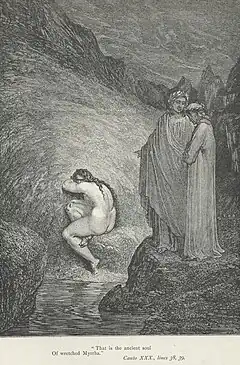

Myrrha appears in the Divine Comedy poem Inferno by Dante Alighieri, where Dante sees her soul being punished in the eighth circle of Hell, in the tenth bolgia (ditch). Here she and other falsifiers such as the alchemists and the counterfeiters suffer dreadful diseases, Myrrha's being madness.[47][48] Myrrha's suffering in the tenth bolgia indicates her most serious sin was not incest[lower-alpha 16] but deceit.[50] Diana Glenn interprets the symbolism in Myrrha's contrapasso as being that her sin is so unnatural and unlawful that she is forced to abandon human society and simultaneously she loses her identity. Her madness in Hell prevents even basic communication which attests to her being contemptuous of the social order in life.[48]

Dante had already shown his familiarity with the myth of Myrrha in a prior letter to Emperor Henry VII, which he wrote on 17 April 1311.[51] Here he compares Florence with "Myrrha, wicked and ungodly, yearning for the embrace of her father, Cinyras";[52] a metaphor, Claire Honess interprets as referring to the way Florence tries to "seduce" Pope Clement V away from Henry VII. It is incestuous because the Pope is the father of all and it is also implied that the city in that way rejects her true husband, the Emperor.[52]

In the poem Venus and Adonis, written by William Shakespeare in 1593 Venus refers to Adonis' mother. In the 34th stanza Venus is lamenting because Adonis is ignoring her approaches and in her heart-ache she says "O, had thy mother borne so hard a mind, She had not brought forth thee, but died unkind."[53] Shakespeare makes a subtle reference to Myrrha later when Venus picks a flower: "She crops the stalk, and in the breach appears, Green dropping sap, which she compares to tears."[54] It has been suggested that these plant juices being compared to tears are a parallel to Myrrha's tears being the drops of myrrh exuding from the myrrh tree.[55]

In another work of Shakespeare, Othello (1603), it has been suggested that he has made another reference. In act 5, scene 2 the main character Othello compares himself to a myrrh tree with its constant stream of tears (Myrrha's tears).[lower-alpha 17] The reference is justified in the way that it draws inspiration from Book X of Ovid's Metamorphoses, just like his previously written poem, Venus and Adonis, did.[57]

The tragedy Mirra by Vittorio Alfieri (written in 1786) is inspired by the story of Myrrha. In the play, Mirra falls in love with her father, Cinyras. Mirra is to be married to Prince Pyrrhus, but decides against it, and leaves him at the altar. In the ending, Mirra has a mental breakdown in front of her father who is infuriated because the prince has killed himself. Owning that she loves Cinyras, Mirra grabs his sword, while he recoils in horror, and kills herself.[58]

The novella Mathilda, written by Mary Shelley in 1820, contains similarities to the myth and mentions Myrrha. Mathilda is left by her father as a baby after her birth causes the death of her mother, and she does not meet her father until he returns sixteen years later. Then he tells her that he is in love with her, and, when she refuses him, he commits suicide.[59] In chapter 4, Mathilda makes a direct allusion: "I chanced to say that I thought Myrrha the best of Alfieri's tragedies."[60] Audra Dibert Himes, in an essay entitled "Knew shame, and knew desire", notes a more subtle reference to Myrrha: Mathilda spends the last night before her father’s arrival in the woods, but as she returns home the next morning the trees seemingly attempt to encompass her. Himes suggests that the trees can be seen as a parallel to Ovid’s metamorphosed Myrrha.[61]

The tragedy Sardanapalus by George Gordon Byron published in 1821 and produced in 1834 is set in Assyria, 640 B.C., under King Sardanapalus. The play deals with the revolt against the extravagant king and his relationship to his favourite slave Myrrha. Myrrha made Sardanapalus appear at the head of his armies, but after winning three successive battles in this way he was eventually defeated. A beaten man, Myrrha persuaded Sardanapalus to place himself on a funeral pyre which she would ignite and subsequently leap onto - burning them both alive.[62][63][64][65] The play has been interpreted as an autobiography, with Sardanapalus as Byron's alter ego, Zarina as Byron's wife Anne Isabella, and Myrrha as his mistress Teresa. At a more abstract level Myrrha is the desire for freedom driving those who feel trapped or bound, as well as being the incarnation of Byron's dream of romantic love.[66] Byron knew the story of the mythical Myrrha, if not directly through Ovid's Metamorphoses, then at least through Alfieri's Mirra, which he was familiar with. In her essay "A Problem Few Dare Imitate", Susan J. Wolfson phrases and interprets the relation of the play Sardanapalus and the myth of Myrrha:[67]

Although [Byron's] own play evades the full import of this complicated association, Myrrha's name means that it [the name's referring to incest, red.] cannot be escaped entirely - especially since Ovid's story of Myrrha's incest poses a potential reciprocal to the nightmare Byron invents for Sardanapalus, of sympathy with the son who is the object of his mother's 'incest'.[68]

In 1997 the myth of Myrrha and Cinyras was one of 24 tales from Ovid's Metamorphoses that were retold by English poet Ted Hughes in his poetical work Tales from Ovid. The work was praised for not directly translating, but instead retelling the story in a language which was as fresh and new for the audience today as Ovid's texts were to his contemporary audience. Hughes was also complimented on his achievements in using humour or horror when describing Myrrha or a flood, respectively.[69] The work received critical acclaim winning the Whitbread Book Of The Year Award 1997[70] and being adapted to the stage in 1999, starring Sirine Saba as Myrrha.[71]

In 1997 American poet Frank Bidart wrote Desire, which was another retelling of the myth of Myrrha as it was presented in the Metamorphoses by Ovid. The case of Myrrha, critic Langdon Hammer notes, is the worst possible made against desire, because the story of Myrrha shows how sex can lead people to destroy others as well as themselves. He comments that "the "precious bitter resin" into which Myrrha's tears are changed tastes bitter and sweet, like Desire as a whole".[72] He further writes: "The inescapability of desire makes Bidart's long story of submission to it a kind of affirmation. Rather than aberrant, the Ovidian characters come to feel exemplary".[72]

John Dryden's translation

In 1700 English poet John Dryden published his translations of myths by Ovid, Homer, and Boccaccio in the volume Fables, Ancient and Modern. Literary critic Anthony W. Lee notes in his essay "Dryden's Cinyras and Myrrha" that this translation, along with several others, can be interpreted as a subtle comment on the political scene of the late seventeenth-century England.[73]

The translation of the myth of Myrrha as it appeared in Ovid's Metamorphoses is suggested as being a critique of the political settlement that followed the Glorious Revolution. The wife of the leader of this revolution, William of Orange, was Mary, daughter of James II. Mary and William were crowned king and queen of England in 1689, and because Dryden was deeply sympathetic to James he lost his public offices and fell into political disfavor under the new reign. Dryden turned to translation and infused these translations with political satire in response - the myth of Myrrha being one of these translations.[73]

In the opening lines of the poem Dryden describes King Cinyras just as Ovid did as a man who had been happier if he had not become a father. Lee suggests that this is a direct parallel to James who could have been counted as happier if he had not had his daughter, Mary, who betrayed him and usurped his monarchical position. When describing the act of incest Dryden uses a monster metaphor. Those lines are suggested as aimed at William III who invaded England from the Netherlands and whose presence Dryden describes as a curse or a punishment, according to Lee. A little further on the Convention Parliament is indicted. Lee suggests that Dryden critiques the intrusiveness of the Convention Parliament, because it acted without constituted legal authority. Finally the daughter, Mary as Myrrha,[lower-alpha 18] is described as an impious outcast from civilization, whose greatest sin was her disrupting the natural line of succession thereby breaking both natural as well as divine statutes which resulted in fundamental social confusion. When Myrrha craves and achieves her father's (Cinyras') bed, Lee sees a parallel to Mary's ascending James' throne: both daughters incestuously occupied the place which belonged to their fathers.[73]

Reading the translation of the myth of Myrrha by Dryden as a comment on the political scene, states Lee, is partly justified by the characterization done by the historian Julian Hoppit on the events of the revolution of 1688:[73]

To most a monarch was God's earthly representative, chosen by Him for the benefit of His people. For men to meddle in that choice was to tamper with the divine order, the inevitable price of which was chaos.[74]

Music

In music, Myrrha was the subject of an 1876 band piece by John Philip Sousa, Myrrha Gavotte[75] and in 1901, Maurice Ravel and André Caplet each wrote cantatas titled Myrrha.[76][77] Caplet finished first over Ravel who was third in the Prix de Rome competition. The competition required that the candidates jumped through a series of academic hoops before entering the final where they were to compose a cantata on a prescribed text.[78] Though it was not the best musical piece, the jury praised Ravel's work for its "melodic charm" and "sincerity of dramatic sentiment".[79] Musical critic Andrew Clements writing for The Guardian commented on Ravel's failures at winning the competition: "Ravel's repeated failure to win the Prix de Rome, the most coveted prize for young composers in France at the turn of the 20th century, has become part of musical folklore."[78]

Italian composer Domenico Alaleona's only opera, premiering in 1920, was entitled Mirra. The libretto drew on the legend of Myrrha while the music was inspired by Claude Debussy's Pelléas et Mélisande (1902) as well as Richard Strauss' Elektra (1909). Suffering from being monotonic, the final showdown between father and daughter, the critics commented, was the only part really making an impact.[80] Mirra remains Alaleona's most ambitious composition and though the music tended to be "eclectic and uneven", it showed "technical enterprise".[81]

More recently, Kristen Kuster created a choral orchestration, Myrrha, written in 2004 and first performed at Carnegie Hall in 2006. Kuster stated that the idea for Myrrha came when she was asked by the American Composers Orchestra to write a love-and-erotica themed concert. The concert was inspired by the myth of Myrrha in Ovid's Metamorphoses and includes excerpts from the volume that "move in and out of the music as though in a dream, or perhaps Myrrha’s memory of the events that shaped her fate," as described by Kuster.[82][83]

Art

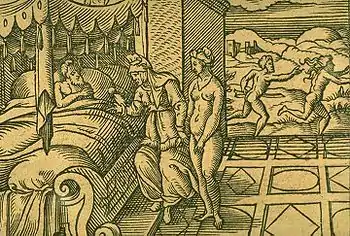

The Metamorphoses of Ovid has been illustrated by several artists through time. In 1563 in Frankfurt, a German bilingual translation by Johann Posthius was published, featuring the woodcuts of renowned German engraver Virgil Solis. The illustration of Myrrha depicts Myrrha's deceiving her father as well as her fleeing from him.[84] In 1717 in London, a Latin-English edition of Metamorphoses was published, translated by Samuel Garth and with plates of French engraver Bernard Picart. The illustration of Myrrha was entitled The Birth of Adonis and featured Myrrha as a tree delivering Adonis while surrounded by women.[85][86][87] In 1857 French engraver Gustave Doré made a series of illustrations to Dante's Divine Comedy, the depiction of Myrrha showing her in the eighth circle of Hell.[47][88]

In 1690, Italian Baroque painter Marcantonio Franceschini depicted Myrrha as a tree while delivering Adonis in The Birth of Adonis. The painting was included in the art exhibition "Captured Emotions: Baroque Painting in Bologna, 1575-1725" at the J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center in Los Angeles, California which lasted from December 16, 2008 through May 3, 2009. Normally the painting is exhibited in the Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (English: Dresden State Art Collections) in Germany as a part of the Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (English: Old Masters Picture Gallery).[89][90]

In 1984, artist Mel Chin created a sculpture based on Doré's illustration of Myrrha for the Divine Comedy. The sculpture was titled "Myrrha of the Post Industrial World" and depicted a nude woman sitting on a rectangular pedestal. It was an outdoor project in Bryant Park, and the skin of the sculpture was made of perforated steel. Inside was a visible skeleton of polystyrene. When finished, the sculpture was 29 feet tall.[91]

Science

Several metamorphosing insects' scientific names reference the myth. Myrrha is a genus of ladybug beetles, such as the 18-spot ladybird (Myrrha octodecimguttata).[92] Libythea myrrha, the club beak, is a butterfly native to India. Polyommatus myrrha is a rare species of butterfly named by Gottlieb August Wilhelm Herrich-Schäffer found on Mount Erciyes in south-eastern Turkey.[93][94] Catocala myrrha is a synonym for a species of moth known as married underwing.[lower-alpha 19][96][97][98] In total the United Kingdom's Natural History Museum lists seven Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) with the myrrha name.[99]

Myrrh is a bitter-tasting, aromatic, yellow to reddish brown gum. It is obtained from small thorny flowering trees of the genus Commiphora, which is a part of the incense-tree family (Burseraceae). There are two main varieties of myrrh: bisabol and herabol. Bisabol is produced by C. erythraea, an Arabian species similar to the C. myrrha, which produces the herabol myrrh. C. myrrha grows in Ethiopia, Arabia, and Somalia.[4][100]

A large asteroid, measuring 124 kilometres (77 mi) is named 381 Myrrha. It was discovered and named on January 10, 1894 by A. Charlois at Nice. The mythical Myrrha inspired the name and her son, Adonis, is the name given to another asteroid, 2101 Adonis.[101][102] Using classical names like Myrrha, Juno, and Vesta when naming minor planets was standard custom at the time when 381 Myrrha was discovered. It was the general opinion that using numbers instead might lead to unnecessary confusion.[103]

See also

Notes

- The word "frankincense" means "fine incense".[9]

- Myrrh is not mentioned in the Qur'an.[8]

- Ovid spoke in his own person in his previous works where he was reputed as a witty and cynical man. Metamorphoses is a purely narrative poem and Ovid leaves his cynicism behind to reveal a sympathetic insight in human emotions.[17]

- According to Ovid Pygmalion was Myrrha's great-grandfather: Pygmalion's daughter, Paphos, was the mother of Cinyras, who was Myrrha's father.[18]

- It is not known exactly how many nights the affair lasted, but a source suggests only three nights.[15]

- Modern day Yemen.[24]

- Following customary usage, the author of Biblioteca is referred to as Apollodorus, but see discussion of historicity of the author: pseudo-Apollodorus.

- This is considered a possible reference to temple prostitution connected with the cult of Aphrodite or Astarte. It is unknown what caused Aphrodite's anger, but it could be neglect of her cult as Cinyras was associated with the cult of the Paphian Aphrodite in Cyprus.[25]

- Antoninus Liberalis' Metamorphoses have parallels to the Metamorphoses of Ovid, due to their using the same source for their individual works: the Heteroioumena by Nicander (2nd century B.C.)[29]

- Bēlos was a Greek name for Ba'al. Orithyia is often associated with the daughter of an Athenian king who was taken away by Boreas, the north wind.[30] In Liberalis' Metamorphoses she is a nymph, though.[31]

- Antoninus Liberalis uses the verb ekmainō, which is used when describing the madness of erotic passion. He uses it when describing Byblis' love as well, and Alcaeus uses it when describing the relationship between Paris and Helen.[30]

- Hippolyte is also the name of the legendary queen of the Amazons, but there is no evidence that this Hippolyte is related in any way.[30]

- This fate of Myrrha's father is also accounted for by Hyginus in his Fabulae, though not in the same story as the rest of the myth.[32]

- E.g. from a love letter written by a courtesan to her lover: "My perfume, my tender Adonis"[40]

- Doll remarks that the union of Cupid and Psyche is a metaphor for the union of love and soul.[15]

- Incest would likely have been categorized as a "carnal sin" by Dante which would have earned her a place in Hell's 2nd circle.[49]

- Othello: "...of one whose subdued eyes,

Albeit unused to the melting mood,

Drop tears as fast as the Arabian trees

Their medicinal gum".[56] - Lee notes the phonetic similarity of the names. If you switch the vowels "Myrrha" becomes "Mary".[73]

- Scientific names may change over time as animals are reclassified and the current standard scientific name for the married underwing is Catocala nuptialias. Catocala myrrha is a scientific synonym of Catocala nuptialis.[95]

References

- Grimal 1974, pp. 94–95

- Ezekiel 8:14

- Watson 1976, p. 736

- "myrrh". The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia. Vol. 8 (15th ed.). U.S.A.: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2003. p. 467.

- Oxford 1971, p. 1888

- Onions, Friedrichsen & Burchfield 1966, p. 600

- Park & Taylor 1858, p. 212

- Musselman 2007, pp. 194–197

- Casson, Lionel (December 1986). "Points of origin". Smithsonian. 17 (9): 148–152.

- Noegel & Rendsburg 2009, p. 184

- Coogan 2009, p. 394

- Song of Solomon 5:5

- Song of Solomon 5:13

- Matthew 2:10-11

- Doll, Mary Aswell (2006). "What Nature Allows the Jealous Laws Forbid: The Cases of Myrrha and Ennis del Mar". Journal of Curriculum Theorizing. 21 (3): 39–45.

- Ovidius Naso 1971, p. 9

- Ovidius Naso 1971, p. 15

- Ovidius Naso 1971, p. 232 (Book X, 296-298)

- Ovidius Naso 1971, pp. 231–245 (Book X, 243-739)

- Ovidius Naso 2003, p. 373

- Ovidius Naso 1971, p. 233 (Book X, 300-303)

- Ovidius Naso 1971, p. 233 (Book X, 311-315)

- Ovidius Naso 1971, pp. 233–238 (Book X, 298-513)

- Stokes, Jamie (2009). "Yemenis: nationality (people of Yemen)". Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. Vol. 1. Infobase Publishing. p. 745.

- Apollodorus 1998, p. 239

- Apollodorus 1998, p. 131 (Book III, 14.3)

- Apollodorus 1998, p. 131 (Book III, 14.4)

- Hyginus 1960, p. 61 (No. LVIII in Myths)

- Liberalis 1992, p. 2

- Liberalis 1992, p. 202

- Liberalis 1992, p. 93 (No. XXXIV)

- Hyginus 1960, p. 162 (No. CCXLII in Myths)

- Servius Commentary on Virgil's Eclogues 10.18

- Forbes Irving, Paul M. C. (1990). Metamorphosis in Greek Myths. Oxford, New York, Toronto: Oxford University Press, Clarendon Press. p. 275. ISBN 0-19-814730-9.

- Newlands 1995, p. 167

- Genesis 19:31-36

- Miller & Tougaw 2002, p. 216

- Detienne 1994, pp. 63–64

- Ellis 2003, p. 191

- From the Palatine Anthology as cited in Detienne 1994, pp. 63

- Ovidius Naso 1971, pp. 228–245 (Book X, 143-739)

- Ovidius Naso 1971, p. 233 (Book X, 304-307)

- Ovidius Naso, Publius (2005). F. J. Miller (ed.). The Metamorphoses: Ovid. New York: Barnes & Noble Classics. p. xxx. ISBN 1-4366-6586-8. as cited in Doll, Mary Aswell (2006). "What Nature Allows the Jealous Laws Forbid: The Cases of Myrrha and Ennis del Mar". Journal of Curriculum Theorizing. 21 (3): 39–45.

- Mullan, John (2008-04-10). "Ten of the best incestuous relationships". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- Josephus 1835, p. 23

- Josephus 1835, p. 384 (Book XIX, chapter 1.13)

- Alighieri 2003, pp. 205–210 (canto XXX, verses 34-48)

- Glenn 2008, pp. 58–59

- Alighieri 2003, p. v

- Alighieri 2003, p. vii

- Alighieri 2007, p. 69

- Alighieri 2007, pp. 78–79

- Shakespeare 1932, p. 732 (stanza 34)

- Shakespeare 1932, p. 755 (stanza 196)

- Bate 1994, p. 58

- Othello, V, II, 357-360 as cited in Bate 1994, p. 187

- Bate 1994, p. 187

- Eggenberger 1972, p. 38

- Whitaker, Jessica Menzo Russel (2002). "Mathilda, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley - Introduction". eNotes. Gale Cengage. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- Shelley, Mary. Mathilda in The Mary Shelley Reader. Oxford University Press, 1990 cited in Shelley 1997, p. 128

- Shelley 1997, p. 123

- Ousby 1993, p. 827

- "Sardanapalus". The New Encyclopædia Britannica: Micropædia. Vol. 10 (15th ed.). U.S.A.: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. 2003. p. 450.

- Hochman 1984, p. 38

- Byron 1823, p. 3

- McGann 2002, pp. 142–150

- Gleckner 1997, pp. 223–224

- Gleckner 1997, p. 224

- Balmer, Josephine (1997-05-04). "What's the Latin for 'the Brookside vice'?". The Independent. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- "Past Winners" (PDF). Costa Book Awards. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-29. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- "THE INFORMATION on; 'Tales from Ovid'". The Independent. 1999-04-23. Retrieved 2011-01-29.

- Hammer, Langdon (1997-11-24). "Poetry and Embodiment". The Nation. Katrina vanden Heuvel. pp. 32–34.

- Lee, Anthony W. (2004). "Dryden's Cinyras and Myrrha". The Explicator. 62 (3): 141–144. doi:10.1080/00144940409597201. S2CID 161754795.

- Hoppit 2002, pp. 21–22

- Bierley 2001, p. 236

- "Maurice Ravel". Allmusic. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- "André Caplet". Allmusic. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- Clements, Andrew (2001-03-23). "Classical CD releases". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- Orenstein 1991, pp. 35–36

- Ashley, Tim (2005-04-08). "Alaleona: Mirra: Mazzola-Gavezzeni/ Gertseva/ Malagnini/ Ferrari/ Chorus and Orchestra of Radio France/ Valcuh". The Guardian. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- C.G. Waterhouse, John. "Alaleona, Domenico". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press.

- "Myrrha in the Making". American Composers Orchestra. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

move in and out of the music as though in a dream, or perhaps Myrrha's memory of the events that shaped her fate

- Kozinn, Allan (2006-05-05). "New Music From American Composers Orchestra at Carnegie Hall". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- Kinney, Daniel; Elizabeth Styron. "Ovid Illustrated: The Reception of Ovid's Metamorphoses in Image and Text". University of Virginia Electronic Text Center. Retrieved 2011-02-27.

- Kinney, Daniel; Elizabeth Styron. "Ovid Illustrated: The Reception of Ovid's Metamorphoses in Image and Text - Fab. X. Myrrha changed to a tree; the Birth of Adonis". University of Virginia Electronic Text Center. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- Kinney, Daniel; Elizabeth Styron. "Ovid Illustrated: The Reception of Ovid's Metamorphoses in Image and Text - Abbé Banier's Ovid commentary Englished from Ovid's Metamorphoses (Garth tr., Amsterdam, 1732)". University of Virginia Electronic Text Center. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- Kinney, Daniel; Elizabeth Styron. "Ovid Illustrated: The Reception of Ovid's Metamorphoses in Image and Text - Preface of Garth Translation (London, 1717) and Banier-Garth (Amsterdam, 1732)". University of Virginia Electronic Text Center. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- Roosevelt 1885, pp. 212–227

- "Captured Emotions: Baroque Painting in Bologna, 1575-1725 Opens at the Getty Museum". Art Knowledge News. Archived from the original on 2011-04-27. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- "Object list: Captured Emotions: Baroque Painting in Bologna, 1575–1725" (PDF). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Center and Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-13. Retrieved 2011-03-15.

- Heller Anderson, Susan; David Bird (1984-08-14). "The See-Through Woman Of Bryant Park". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- A. G., Duff (2008). "Checklist of Beetles of the British Isles" (PDF). The Coleopterist. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-05. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- Beccaloni, G.; Scoble, M.; Kitching, I.; Simonsen, T.; Robinson, G.; Pitkin, B.; Hine, A.; Lyal, C., eds. (2003). "Cupido myrrha". The Global Lepidoptera Names Index. Natural History Museum. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- Naturhistorisches Museum (Austria) (1905). Annalen des Naturhistorischen Museums in Wien [Museum of Natural History of Vienna annual] (in German). Vol. 20. Wien, Naturhistorisches Museum. p. 197.

'Zwei ♂ dieser seltenen Art aus dem Erdschias-Gebiet' Translation:Two males of these rare species from the Erciyes region.

- Gall, Lawrence F; Hawks, David C. (1990). "Systematics of Moths in the Genus Catocala (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae)". Fieldiana. Field Museum of Natural History (1414): 12. Archived from the original on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2011-02-03.

- Oehlke, Bill. "Catocala: Classification and Common Names". P. E. I. R. T. A. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- "Attributes of Catocala nuptialis". Butterflies and Moths of North America. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- "Catocala myrrha". Catalogue of Life - 2010 Annual Checklist. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- Natural History Museum, London. "LepIndex - The Global Lepidoptera Names Index for taxon myrrha". Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- "Species identity - Commiphora myrrha". International center for research in agroforestry. Archived from the original on 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2011-02-02.

- Lewis & Prinn 1984, p. 371

- Schmadel 2003, p. 372

- Schmadel 2003, pp. 4–5

Works cited

- Alighieri, Dante (2003). The Inferno of Dante Alighieri. Translated by Zimmerman, Seth. iUniverse. pp. vii-210. ISBN 978-0-595-28090-2.

- Alighieri, Dante (2007). Dante Alighieri: four political letters. Translated by Honess, Claire E. MHRA. ISBN 978-0-947623-70-8.

- Apollodorus (1998). The Library of Greek Mythology. pp. 131–239. ISBN 978-0-19-283924-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Bate, Jonathan (1994). Shakespeare and Ovid. Oxford University Press. pp. 58–187. ISBN 978-0-19-818324-2.

- Bierley, Paul E. (2001). John Philip Sousa: American Phenomenon. Alfred Music Publishing. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-7579-0612-1.

- Byron, George Gordon N. (1823). Sardanapalus: a tragedy. J. Murray. Retrieved 2011-02-22.

sardanapalus.

- Coogan, Michael D. (2009). A Brief Introduction to the Old Testament: The Hebrew Bible in Its Context. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 394. ISBN 978-0-19-533272-8.

- Detienne, Marcel (1994). Janet Lloyd (ed.). The gardens of Adonis: spices in Greek mythology. Princeton University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-691-00104-3.

- Eggenberger, David (1972). McGraw-Hill encyclopedia of world drama. Vol. 1. McGraw-Hill. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-07-079567-9.

- Ellis, James Richard (2003). Sexuality and citizenship: metamorphosis in Elizabethan erotic verse. University of Toronto Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-8020-8735-5.

- Gleckner, Robert F. (1997). "'A Problem Few Dare Imitate': Sardanapalus and 'Effeminate Character'". In Beatty, Bernard G. (ed.). The plays of Lord Byron: critical essays. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-0-85323-891-1.

- Glenn, Diana (2008). "Myrrha". Dante's reforming mission and women in the Comedy. Troubador Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-906510-23-7.

- Grimal, Pierre (1974). Larousse World Mythology. The Hamlyn Publishing Group Limited. pp. 94–132. ISBN 978-0-600-02366-1. OCLC 469569331.

- Hochman, Stanley, ed. (1984). McGraw-Hill encyclopedia of world drama: an international reference work in 5 volumes. Vol. 4. McGraw-Hill. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-07-079169-5.

- Hoppit, Julian (2002). A Land of Liberty?: England 1689-1727. Berkeley: Oxford University Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-19-925100-1.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius (1960). Mary A. Grant (ed.). The Myths of Hyginus. pp. 61–162. ISBN 1-890482-93-5.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Josephus, Flavius (1835). William Whiston (ed.). The works of Flavius Josephus: the learned and authentic Jewish historian and celebrated warrior. With three dissertations, concerning Jesus Christ, John the Baptist, James the Just, God's command to Abraham, & c. and explanatory notes and observation. Armstrong and Plaskitt, and Plaskitt & Co. Retrieved 2011-03-11.

- Lewis, John S.; Prinn, Ronald G. (1984). Planets and their atmospheres: origin and evolution. Academic Press. pp. 470. ISBN 978-0-12-446580-0.

- Liberalis, Antoninus (1992). Francis Celoria (ed.). The Metamorphoses of Antoninus Liberalis: A translation with a commentary. London: Routledge. pp. 93–202. ISBN 978-0-415-06896-3. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- McGann, Jerome J. (2002). James Soderholm (ed.). Byron and romanticism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00722-1.

- Miller, Nancy K.; Tougaw, Jason Daniel (2002). Extremities: trauma, testimony, and community. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07054-9.

- Musselman, Lytton John (2007). Figs, dates, laurel, and myrrh: plants of the Bible and the Quran. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press, Inc. pp. 194–200. ISBN 978-0-88192-855-6.

- Newlands, Carole Elizabeth (1995). Playing with time: Ovid and the Fasti. Cornell University Press. pp. 167. ISBN 978-0-8014-3080-0.

- Noegel, Scott B.; Rendsburg, Gary A. (29 Oct 2009). Solomon's Vineyard: Literary and Linguistic Studies in the Song of Songs (Ancient Israel and Its Literature). Society of Biblical Literature. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-58983-422-4.

- Onions, Charles; Friedrichsen, George; Burchfield, R. (1966). The Oxford dictionary of English etymology. Oxford University Press. p. 600. ISBN 978-0-19-861112-7.

- Orenstein, Arbie (1991). Ravel: man and musician. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 35–36. ISBN 978-0-486-26633-6.

- Ousby, Ian (1993). "Sardanapalus". The Cambridge guide to literature in English. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44086-8.

- Ovidius Naso, Publius (1971). Mary M. Innes (ed.). The Metamorphoses of Ovid. Penguin Books Ltd. pp. 232–238. ISBN 1-4366-6586-8.

- Ovidius Naso, Publius (2003). Michael Simpson (ed.). The Metamorphoses of Ovid. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 373–376. ISBN 978-1-55849-399-5.

- The compact edition of the Oxford English dictionary: complete text reproduced micrographically. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. 1971. p. 1888.

- Park, Edwards; Taylor, Samuel (1858). Edwards A. Park; Samuel H. Taylor (eds.). Bibliotheca Sacra. Vol. 15. Allen, Morrill and Wardwell. p. 212.

- Roosevelt, Blanche (1885). Life and Reminiscence of Gustave Doré. New York: Cassell & Co., Ltd.

- Schmadel, Lutz D. (2003). Dictionary of minor planet names. Springer. pp. 4–372. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3.

- Shakespeare, William (1932). "Venus and Adonis". Histories and poems. Aldine House, Bedford Street, London W.C.2: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. pp. 727–755. ISBN 0-679-64189-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Shelley, Mary (1997). Conger, Syndy; Frank, Frederick; O'Dea, Gregory (eds.). Iconoclastic departures: Mary Shelley after Frankenstein: essays in honor of the bicentenary of Mary Shelley's birth. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 362. ISBN 978-0-8386-3684-8. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- Watson, Owen (1976). Owen Watson (ed.). Longman modern English dictionary. Longman. pp. 736. ISBN 978-0-582-55512-9.

External links

Media related to Myrrha at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Myrrha at Wikimedia Commons- The myth of Myrrha retold in comic, by Glynnis Fawkes

- The Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (images of Myrrha)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)