White Nile

The White Nile (Arabic: النيل الأبيض an-nīl al-'abyaḍ) is a river in Africa, one of the two main tributaries of the Nile, the other being the Blue Nile. The name comes from the clay sediment carried in the water that changes the water to a pale color.[4]

| White Nile Victoria Nile, Albert Nile, Mountain Nile | |

|---|---|

A steel Bailey bridge spans the White Nile at Juba, South Sudan | |

| Location | |

| Country | Sudan, South Sudan, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia |

| Cities | Jinja, Uganda, Juba, South Sudan, Khartoum, Sudan |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | White Nile |

| • location | Burundi[1] or Rwanda[2] |

| • coordinates | 2°16′56″S 29°19′52″E |

| Length | 3,700 km (2,300 mi)[3] |

| Basin size | 1,800,000 km2 (690,000 sq mi) |

| Discharge | |

| • average | 878 m3/s (31,000 cu ft/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Albert Nile, Bahr el Ghazal |

| • right | Aswa, Sobat |

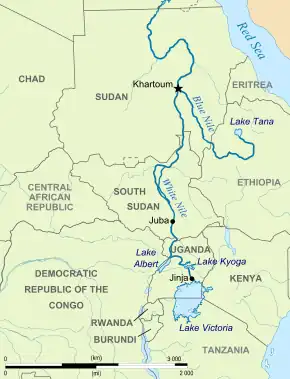

In the strict meaning, "White Nile" refers to the river formed at Lake No, at the confluence of the Bahr al Jabal and Bahr el Ghazal Rivers. In the wider sense, "White Nile" refers to all the stretches of river draining from Lake Victoria through to the merger with the Blue Nile: the "Victoria Nile" from Lake Victoria via Lake Kyoga to Lake Albert, then the "Albert Nile" to the South Sudan border, and then the "Mountain Nile" or "Bahr-al-Jabal" down to Lake No.[5] "White Nile" may sometimes include the headwaters of Lake Victoria, the most remote of which being 3,700 km (2,300 mi) from the Blue Nile.[3]

The 19th-century search by Europeans for the source of the Nile was mainly focused on the White Nile, which disappeared into the depths of what was then known as "Darkest Africa".

Course

Headwaters

The Kagera River, which flows into Lake Victoria near the Tanzanian town of Bukoba, is the longest feeder river for Lake Victoria, although sources do not agree on which is the longest tributary of the Kagera, and hence the most distant source of the Nile.[6] The source of the Nile can be considered to be either the Ruvyironza, which emerges in Bururi Province, Burundi[7] (near Bukirasaz), or the Nyabarongo, which flows from Nyungwe Forest in Rwanda.[8]

These two feeder rivers meet near Rusumo Falls on the border between Rwanda and Tanzania. These waterfalls are known for an event on 28–29 April 1994, when 250,000 Rwandans crossed the bridge at Rusumo Falls into Ngara, Tanzania, in 24 hours, in what the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees called "the largest and fastest refugee exodus in modern times". The Kagera forms part of the Rwanda–Tanzania and Tanzania–Uganda borders before flowing into Lake Victoria.

In Uganda

The White Nile in Uganda goes under the name of "Victoria Nile" from Lake Victoria via Lake Kyoga to Lake Albert, and then as the "Albert Nile" from there to the border with South Sudan.

Victoria Nile

The Victoria Nile starts at the outlet of Lake Victoria, at Jinja, Uganda, on the northern shore of the lake.[9] Downstream from the Nalubaale Power Station and the Kiira Power Station at the outlet of the lake, the river goes over Bujagali Falls (the location of the Bujagali Power Station) about 15 km (9.3 mi) downstream from Jinja. The river then flows northwest through Uganda to Lake Kyoga in the centre of the country, thence west to Lake Albert.

At Karuma Falls, the river flows under Karuma Bridge (2°14′45.40″N 32°15′9.05″E) at the southeastern corner of Murchison Falls National Park. During much of the insurgency of the Lord's Resistance Army, Karuma Bridge, built in 1963 to help the cotton industry, was the key stop on the way to Gulu, where vehicles gathered in convoys before being provided with a military escort for the final run north. In 2009, the government of Uganda announced plans to construct a 750-megawatt hydropower project several kilometres north of the bridge, which was scheduled for completion in 2016.[10] The World Bank had approved funding a smaller 200-megawatt power plant, but Uganda opted for a larger project, which the Ugandans will fund internally if necessary.[11]

Just before entering Lake Albert, the river is compressed into a passage just seven meters wide at Murchison Falls, marking its entry into the western branch of the East African Rift. The river then flows into Lake Albert opposite the Blue Mountains in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The stretch of river from Lake Kyoga to Lake Albert is sometimes called the "Kyoga Nile".[12]

Albert Nile

The river draining from Lake Albert to the north is called the "Albert Nile". It separates the West Nile sub-region of Uganda from the rest of the country. A bridge passes over the Albert Nile near its inlet in Nebbi District, but no other bridge over this section has been built. A ferry connects the roads between Adjumani and Moyo, and navigation of the river is otherwise done by small boat or canoe.

In South Sudan and Sudan

From the point at which the river enters South Sudan from Uganda, the river goes under the name of "Mountain Nile". From Lake No in South Sudan the river becomes the "White Nile" in its strictest sense, and so continues northwards into Sudan where it ends at its confluence with the Blue Nile.

Mountain Nile

From Nimule in South Sudan, close to the border with Uganda, the river becomes known as the "Mountain Nile" or "Baḥr al-Jabal" (also "Baḥr el-Jebel", بحر الجبل), literally Mountain River" or "River of the Mountain".[13][14] The Southern Sudanese state of Central Equatoria through which the river flows was known as Bahr al-Jabal until 2006.[15]

The southern stretch of the river encounters several rapids before reaching the Sudan plain and the vast swamp of the Sudd. It makes its way to Lake No, where it merges with the Bahr el Ghazal and there forms the White Nile.[16][17] An anabranch river called Bahr el Zeraf flows out of the Bahr al-Jabal at and flows through the Sudd, to eventually join the White Nile. The Mountain Nile cascades through narrow gorges and over a series of rapids that includes the Fula (Fola) Rapids.[17][18]

White Nile proper

To some people, the White Nile starts at the confluence of the Mountain Nile with the Bahr el Ghazal at Lake No.[16]

The 120 kilometers of White Nile that flow east from Lake No to the mouth of the Sobat are very gently sloping and hold many swamps and lagoons.[19] When in flood, the Sobat River tributary carries a large amount of sediment, adding greatly to the White Nile's pale color.[20] From South Sudan's second city Malakal, the river runs slowly but swamp-free into Sudan and north to Khartoum. Downstream from Malakal lies Kodok, the site of the 1898 Fashoda Incident that marked an end to the Scramble for Africa.

In Sudan the river lends its name to the Sudanese state of White Nile, before merging with the larger Blue Nile at Khartoum and forming the River Nile.

Inland waterways

The White Nile is a navigable waterway from the Lake Albert to Khartoum through Jebel Aulia Dam, only between Juba and Uganda requires the river upgrade or channel to make it navigable.

During part of the year the rivers are navigable up to Gambela, Ethiopia, and Wau, South Sudan.

References

- "Nile Africa | Africa Nile | Nile Valley | Mystery Nile | Nile White | Egypt Nile | Ancient Capital Nile". 10 January 2007. Archived from the original on 10 January 2007.

- "Team reaches Nile's 'true source'". 31 March 2006. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2020 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- Penn, James R. (2001). Rivers of the World: A Social, Geographical, and Environmental Sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. p. 299. ISBN 9781576070420. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- The New American Cyclopaedia: A Popular Dictionary of General Knowledge, Volume 12. 1867. p. 362. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- Dumont, Henri J. (2009). The Nile: Origin, Environments, Limnology and Human Use. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 344–345. ISBN 9781402097263. Archived from the original on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 30 March 2023.

- McLeay, cam (2 July 2006). "The truth about the source of R. Nile". New Vision. Archived from the original on 9 April 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Nile River". Archived from the original on 10 January 2007. Retrieved 5 February 2011.

- "Team reaches Nile's 'true source'". BBC News. 31 March 2006. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- vanden Bossche, J.-P.; Bernacsek, G. M. (1990). Source Book for the Inland Fishery Resources of Africa, Issue 18, Volume 1. Food and Agriculture Organization, United Nations. p. 291. ISBN 92-5-102983-0. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Holland, Hereward (8 May 2009). "Uganda To Increase Capacity of Electricity Project". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- Wacha, Joe (29 October 2011). "Uganda Oil Money to Finance Karuma Power Project". Uganda Radio Network Online. Archived from the original on 19 April 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- The Indian Journal of International Law: Official Organ of the Indian Society of International Law. M.K. Nawaz. 1980. p. 398. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- The Arabic word baḥr (بحر) can refer to either a sea or a large river

- Garstin, William Edmund; Cana, Frank Richardson (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). pp. 692–699.

- "Southern Sudan Bahr al-Jabal State changes name". Sudan Tribune. 16 April 2006. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- Parsons, Ellen C. (1905). Christus Liberator: An Outline Study of Africa. Macmillan Company. p. 7. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- The Source of the Nile: Rwenzori Mountains National Park, archived from the original on 3 August 2020, retrieved 20 August 2020

- "Nile River (Mountain) | Waterbodies.org". www.waterbodies.org. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- Shahin, Mamdouh (1985). Hydrology of the Nile Basin. Elsevier. p. 40. ISBN 9780444424334. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2017.

- "Sobat River". Encyclopædia Britannica (Online Library ed.). Retrieved 21 January 2008.

External links

- Nile inland Waterways

- South Sudan Waterway Assessment

- Feasibility study river barge system (Cranes on trucks/loader cranes and pallets can increase efficiency)