Anal sex

Anal sex or anal intercourse is generally the insertion and thrusting of the erect penis into a person's anus, or anus and rectum, for sexual pleasure.[1][2][3] Other forms of anal sex include anal fingering, the use of sex toys, anilingus, pegging,[4][5] as well as electrostimulation and erotic torture such as figging. Although anal sex most commonly means penile–anal penetration,[3][4][6] sources sometimes use anal intercourse to exclusively denote penile–anal penetration, and anal sex to denote any form of anal sexual activity, especially between pairings as opposed to anal masturbation.[6][7]

While anal sex is commonly associated with male homosexuality, research shows that not all gay men engage in anal sex and that it is not uncommon in heterosexual relationships.[2][8][9] Types of anal sex can also be a part of lesbian sexual practices.[10] People may experience pleasure from anal sex by stimulation of the anal nerve endings, and orgasm may be achieved through anal penetration – by indirect stimulation of the prostate in men, indirect stimulation of the clitoris or an area of the vagina (sometimes called the G-spot) in women, and other sensory nerves (especially the pudendal nerve).[2][4][11] However, people may also find anal sex painful, sometimes extremely so,[12][13] which may be due to psychological factors in some cases.[13]

As with most forms of sexual activity, anal sex participants risk contracting sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Anal sex is considered a high-risk sexual practice because of the vulnerability of the anus and rectum. The anal and rectal tissue are delicate and do not provide lubrication like the vagina does, so they can easily tear and permit disease transmission, especially if a personal lubricant is not used.[3][2][14] Anal sex without protection of a condom is considered the riskiest form of sexual activity,[14][15][16] and therefore health authorities such as the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend safe sex practices for anal sex.[17]

Strong views are often expressed about anal sex. It is controversial in various cultures, especially with regard to religious prohibitions. This is commonly due to prohibitions against anal sex among males or teachings about the procreative purpose of sexual activity.[5][7] It may be considered taboo or unnatural, and is a criminal offense in some countries, punishable by corporal or capital punishment.[5][7] By contrast, anal sex may also be considered a natural and valid form of sexual activity as fulfilling as other desired sexual expressions, and can be an enhancing or primary element of a person's sex life.[5][7]

Anatomy and stimulation

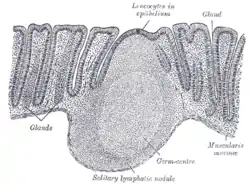

The abundance of nerve endings in the anal region and rectum can make anal sex pleasurable for men and women.[4][2][5] The internal and external sphincter muscles control the opening and closing of the anus; these muscles, which are sensitive membranes made up of many nerve endings, facilitate pleasure or pain during anal sex.[2][5] Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia states that "the inner third of the anal canal is less sensitive to touch than the outer two-thirds, but is more sensitive to pressure" and that "the rectum is a curved tube about eight or nine inches long and has the capacity, like the anus, to expand".[5]

Research indicates that anal sex occurs significantly less frequently than other sexual behaviors,[1] but its association with dominance and submission, as well as taboo, makes it an appealing stimulus to people of all sexual orientations.[5][18][19] In addition to sexual penetration by the penis, people may use sex toys such as a dildo, a butt plug or anal beads, engage in anal fingering, anilingus, pegging, anal masturbation, figging or fisting for anal sexual activity, and different sex positions may also be included.[5][20] Fisting is the least practiced of the activities,[21] partly because it is uncommon that people can relax enough to accommodate an object as big as a fist being inserted into the anus.[5]

In a male receptive partner, being anally penetrated can produce a pleasurable sensation due to the object of insertion rubbing or brushing against the prostate through the anal wall.[4][11] This can result in pleasurable sensations and can lead to an orgasm in some cases.[4][11] Prostate stimulation can produce a deeper orgasm, sometimes described by men as more widespread and intense, longer-lasting, and allowing for greater feelings of ecstasy than orgasm elicited by penile stimulation only.[4][11] The prostate is located next to the rectum and is the larger, more developed male homologue (variation) to the female Skene's glands.[22] It is also typical for a man to not reach orgasm as a receptive partner solely from anal sex.[23][24]

General statistics indicate that 70–80% of women require direct clitoral stimulation to achieve orgasm.[11][25][26] The vaginal walls contain significantly fewer nerve endings than the clitoris (which has many nerve endings specifically intended for orgasm), and therefore intense sexual pleasure, including orgasm, from vaginal sexual stimulation is less likely to occur than from direct clitoral stimulation in the majority of women.[27][28][29] The clitoris is composed of more than the externally visible glans (head).[2][30] The vagina, for example, is flanked on each side by the clitoral crura, the internal legs of the clitoris, which are highly sensitive and become engorged with blood when sexually aroused.[31][32][33] Indirect stimulation of the clitoris through anal penetration may be caused by the shared sensory nerves, especially the pudendal nerve, which gives off the inferior anal nerves and divides into the perineal nerve and the dorsal nerve of the clitoris.[4] Although the anus has many nerve endings, their purpose is not specifically for inducing orgasm, and so a woman achieving orgasm solely by anal stimulation is rare.[34][35]

The Gräfenberg spot, or G-spot, is a debated area of female anatomy, particularly among doctors and researchers,[27][36][28] but it is typically described as being located behind the female pubic bone surrounding the urethra and accessible through the anterior wall of the vagina; it and other areas of the vagina are considered to have tissue and nerves that are related to the clitoris.[31][27][28] Direct stimulation of the clitoris, a G-spot area, or both, while engaging in anal sex can help some women enjoy the activity and reach orgasm during it.[2][37]

Stimulation from anal sex can additionally be affected by popular perception or portrayals of the activity, such as erotica or pornography. In pornography, anal sex is commonly portrayed as a desirable, painless routine that does not require personal lubricant; this can result in couples performing anal sex without care, and men and women believing that it is unusual for women, as receptive partners, to find discomfort or pain instead of pleasure from the activity.[6][38][39][40] By contrast, each person's sphincter muscles react to penetration differently, the anal sphincters have tissues that are more prone to tearing, and the anus and rectum do not provide lubrication for sexual penetration like the vagina does. Researchers say adequate application of a personal lubricant, relaxation, and communication between sexual partners are crucial to avoid pain or damage to the anus or rectum.[2][13][41] Additionally, ensuring that the anal area is clean and the bowel is empty, for both aesthetics and practicality, may be desired by participants.[21]

Male to female

Behaviors and views

The anal sphincters are usually tighter than the pelvic muscles of the vagina, which can enhance the sexual pleasure for the inserting male during male-to-female anal intercourse because of the pressure applied to the penis.[3][37][18] Men may also enjoy the penetrative role during anal sex because of its association with dominance, because it is made more alluring by a female partner or society in general insisting that it is forbidden, or because it presents an additional option for penetration.[5][18]

While some women find being a receptive partner during anal intercourse painful or uncomfortable, or only engage in the act to please a male sexual partner, other women find the activity pleasurable or prefer it to vaginal intercourse.[6][37][42][43]

In a 2010 clinical review article of heterosexual anal sex, anal intercourse is used to specifically denote penile-anal penetration, and anal sex is used to denote any form of anal sexual activity. The review suggests that anal sex is exotic among the sexual practices of some heterosexuals and that "for a certain number of heterosexuals, anal intercourse is pleasurable, exciting, and perhaps considered more intimate than vaginal sex".[6]

Anal intercourse is sometimes used as a substitute for vaginal intercourse during menstruation.[5] The likelihood of pregnancy occurring during anal sex is greatly reduced, as anal sex alone cannot lead to pregnancy unless sperm is somehow transported to the vaginal opening. Because of this, some couples practice anal intercourse as a form of contraception, often in the absence of a condom.[5][38][44]

Male-to-female anal sex is commonly viewed as a way of preserving female virginity because it is non-procreative and does not tear the hymen; a person, especially a teenage girl or woman, who engages in anal sex or other sexual activity with no history of having engaged in vaginal intercourse is often regarded among heterosexuals and researchers as not having yet experienced virginity loss. This is sometimes called technical virginity.[45][46][47][48] Heterosexuals may view anal sex as "fooling around" or as foreplay; scholar Laura M. Carpenter stated that this view "dates to the late 1600s, with explicit 'rules' appearing around the turn of the twentieth century, as in marriage manuals defining petting as 'literally every caress known to married couples but does not include complete sexual intercourse.'"[45]

Prevalence

Because most research on anal intercourse addresses men who have sex with men, little data exists on the prevalence of anal intercourse among heterosexual couples.[6][49] In Kimberly R. McBride's 2010 clinical review on heterosexual anal intercourse and other forms of anal sexual activity, it is suggested that changing norms may affect the frequency of heterosexual anal sex. McBride and her colleagues investigated the prevalence of non-intercourse anal sex behaviors among a sample of men (n=1,299) and women (n=1,919) compared to anal intercourse experience and found that 51% of men and 43% of women had participated in at least one act of oral–anal sex, manual–anal sex, or anal sex toy use.[6] The report states the majority of men (n=631) and women (n=856) who reported heterosexual anal intercourse in the past 12 months were in exclusive, monogamous relationships: 69% and 73%, respectively.[6] The review added that because "relatively little attention [is] given to anal intercourse and other anal sexual behaviors between heterosexual partners", this means that it is "quite rare" to have research "that specifically differentiates the anus as a sexual organ or addresses anal sexual function or dysfunction as legitimate topics. As a result, we do not know the extent to which anal intercourse differs qualitatively from coitus."[6]

According to a 2010 study from the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB) that was authored by Debby Herbenick et al., although anal intercourse is reported by fewer women than other partnered sex behaviors, partnered women in the age groups between 18 and 49 are significantly more likely to report having anal sex in the past 90 days. Women engaged in anal intercourse less commonly than men. Vaginal intercourse was practiced more than insertive anal intercourse among men, but 13% to 15% of men aged 25 to 49 practiced insertive anal intercourse.[50][51]

With regard to adolescents, limited data also exists.[49] This may be because of the taboo nature of anal sex and that teenagers and caregivers subsequently avoid talking to one another about the topic. It is also common for subject review panels and schools to avoid the subject.[49] A 2000 study found that 22.9% of college students who self-identified as non-virgins had anal sex. They used condoms during anal sex 20.9% of the time as compared with 42.9% of the time with vaginal intercourse.[49]

Anal sex being more common among heterosexuals today than it was previously has been linked to the increase in consumption of anal pornography among men, especially among those who view it on a regular basis.[39][40][52] Seidman et al. argued that "cheap, accessible and, especially, interactive media have enabled many more people to produce as well as consume pornography", and that this modern way of producing pornography, in addition to the buttocks and anus having become more eroticized, has led to a significant interest in or obsession with anal sex among men.[52]

Male to male

Behaviors and views

Historically, anal sex has been commonly associated with male homosexuality. However, many gay men and men who have sex with men in general (those who identify as gay, bisexual, heterosexual or have not identified their sexual identity) do not engage in anal sex.[8][9][53][54] Among men who have anal sex with other men, the insertive partner may be referred to as the top and the one being penetrated may be referred to as the bottom. Those who enjoy either role may be referred to as versatile.[55][56]

Gay men who prefer anal sex may view it as their version of intercourse and a natural expression of intimacy that is capable of providing pleasure.[19][53][57] The notion that it might resonate with gay men with the same emotional significance that vaginal sex resonates with heterosexuals has also been considered.[57][58] Some men who have sex with men, however, believe that being a receptive partner during anal sex questions their masculinity.[59][60]

Men who have sex with men may also prefer to engage in frot or other forms of mutual masturbation because they find it more pleasurable or more affectionate, to preserve technical virginity, or as safe sex alternatives to anal sex,[53][55][61] while other frot advocates denounce anal sex as degrading to the receptive partner and unnecessarily risky.[58][62]

Prevalence

Reports regarding the prevalence of anal sex among gay men and other men who have sex with men vary. A survey in The Advocate in 1994 indicated that 46% of gay men preferred to penetrate their partners, while 43% preferred to be the receptive partner.[55] Other sources suggest that roughly three-fourths of gay men have had anal sex at one time or another, with an equal percentage participating as tops and bottoms.[55] A 2012 NSSHB sex survey in the U.S. suggests high lifetime participation in anal sex among gay men: 83.3% report ever taking part in anal sex in the insertive position and 90% in the receptive position, even if only between a third and a quarter self-report very recent engagement in the practice, defined as 30 days or less.[63]

Oral sex and mutual masturbation are more common than anal stimulation among men in sexual relationships with other men.[1][53][64] According to Weiten et al., anal intercourse is generally more popular among gay male couples than among heterosexual couples, but "it ranks behind oral sex and mutual masturbation" among both sexual orientations in prevalence.[1] Wellings et al. reported that "the equation of 'homosexual' with 'anal' sex among men is common among lay and health professionals alike" and that "yet an Internet survey of 180,000 MSM across Europe (EMIS, 2011) showed that oral sex was most commonly practised, followed by mutual masturbation, with anal intercourse in third place".[9]

Female to male

Women may sexually stimulate a man's anus by fingering the exterior or interior areas of the anus; they may also stimulate the perineum (which, for males, is between the base of the scrotum and the anus), massage the prostate or engage in anilingus.[5][21][65] Sex toys, such as a dildo, may also be used.[5][21] The practice of a woman penetrating a man's anus with a strap-on dildo for sexual activity is called pegging.[20][66]

It is common for heterosexual men to reject being receptive partners during anal sex because they believe it is a feminine act, can make them vulnerable, or contradicts their sexual orientation; they may believe being a receptive partner is indicative that they are gay.[21][67] Reece et al. reported in 2010 that receptive anal intercourse is infrequent among men overall, stating that "an estimated 7% of men 14 to 94 years old reported being a receptive partner during anal intercourse".[68]

The BMJ stated in 1999:

There are little published data on how many heterosexual men would like their anus to be sexually stimulated in a heterosexual relationship. Anecdotally, it is a substantial number. What data we do have almost all relate to penetrative sexual acts, and the superficial contact of the anal ring with fingers or the tongue is even less well documented but may be assumed to be a common sexual activity for men of all sexual orientations.[69]

Female to female

With regard to lesbian sexual practices, anal sex includes anal fingering, use of a dildo or other sex toys, or anilingus.[10][70]

There is less research on anal sexual activity among women who have sex with women compared to couples of other sexual orientations. In 1987, a non-scientific study (Munson) was conducted of more than 100 members of a lesbian social organization in Colorado. When asked what techniques they used in their last ten sexual encounters, lesbians in their 30s were twice as likely as other age groups to engage in anal stimulation (with a finger or dildo).[2] A 2014 study of partnered lesbian women in Canada and the U.S. found that 7% engaged in anal stimulation or penetration at least once a week; about 10% did so monthly and 70% did not at all.[71] Anilingus is also less often practiced among female same-sex couples.[72][73]

Health risks

General risks

Anal sex can expose its participants to two principal dangers: infections due to the high number of infectious microorganisms not found elsewhere on the body, and physical damage to the anus and rectum due to their fragility.[14][16] Unprotected penile-anal penetration, colloquially known as barebacking,[74] carries a higher risk of passing on sexually transmitted infections (STIs) because the anal sphincter is a delicate, easily torn tissue that can provide an entry for pathogens.[14][16] Use of condoms, ample lubrication to reduce the risk of tearing,[2][41] and safer sex practices in general, reduce the risk of STIs.[16][75] However, a condom can break or otherwise come off during anal sex, and this is more likely to happen with anal sex than with other sex acts because of the tightness of the anal sphincters during friction.[16]

Unprotected receptive anal sex (with an HIV positive partner) is the sex act most likely to result in HIV transmission.[14][16]

As with other sexual practices, people without sound knowledge about the sexual risks involved are susceptible to STIs. Because of the view that anal sex is not "real sex" and therefore does not result in virginity loss, or pregnancy, teenagers and other young people may consider vaginal intercourse riskier than anal intercourse and believe that a STI can only result from vaginal intercourse.[76][77][78] It may be because of these views that condom use with anal sex is often reported to be low and inconsistent across all groups in various countries.[76]

Although anal sex alone does not lead to pregnancy, pregnancy can still occur with anal sex or other forms of sexual activity if the penis is near the vagina (such as during intercrural sex or other genital-genital rubbing) and its sperm is deposited near the vagina's entrance and travels along the vagina's lubricating fluids; the risk of pregnancy can also occur without the penis being near the vagina because sperm may be transported to the vaginal opening by the vagina coming in contact with fingers or other non-genital body parts that have come in contact with semen.[79][80]

There are a variety of factors that make male-to-female anal intercourse riskier than vaginal intercourse for women, including the risk of HIV transmission being higher for anal intercourse than for vaginal intercourse.[3][81][82] The risk of injury to the woman during anal intercourse is also significantly higher than the risk of injury to her during vaginal intercourse because of the durability of the vaginal tissues compared to the anal tissues.[3][83][84] Additionally, if a man moves from anal intercourse immediately to vaginal intercourse without a condom or without changing it, infections can arise in the vagina (or urinary tract) due to bacteria present within the anus; these infections can also result from switching between vaginal sex and anal sex by the use of fingers or sex toys.[2][3][85]

Pain during receptive anal sex among gay men (or men who have sex with men) is formally known as anodyspareunia.[13] In one study, 61% of gay or bisexual men said they experienced painful receptive anal sex and that it was the most frequent sexual difficulty they had experienced. By contrast, 24% of gay or bisexual men stated that they always experienced some degree of pain during anal sex,[13] and about 12% of gay men find it too painful to pursue receptive anal sex; it was concluded that the perception of anal sex as painful is as likely to be psychologically or emotionally based as it is to be physically based.[13][86] Factors predictive of pain during anal sex include inadequate lubrication, feeling tense or anxious, lack of stimulation, as well as lack of social ease with being gay and being closeted. Research has found that psychological factors can in fact be the primary contributors to the experience of pain during anal intercourse and that adequate communication between sexual partners can prevent it, countering the notion that pain is always inevitable during anal sex.[13][86]

Damage

Anal sex can exacerbate hemorrhoids and therefore result in bleeding; in other cases, the formation of a hemorrhoid is attributed to anal sex.[3][87] If bleeding occurs as a result of anal sex, it may also be because of a tear in the anal or rectal tissues (an anal fissure) or perforation (a hole) in the colon, the latter of which being a serious medical issue that should be remedied by immediate medical attention.[3][87] Because of the rectum's lack of elasticity, the anal mucous membrane being thin, and small blood vessels being present directly beneath the mucous membrane, tiny tears and bleeding in the rectum usually result from penetrative anal sex, though the bleeding is usually minor and therefore usually not visible.[16]

By contrast to other anal sexual behaviors, anal fisting poses a more serious danger of damage due to the deliberate stretching of the anal and rectal tissues; anal fisting injuries include anal sphincter lacerations and rectal and sigmoid colon (rectosigmoid) perforation, which might result in death.[5][88]

Repetitive penetrative anal sex may result in the anal sphincters becoming weakened, which may cause rectal prolapse or affect the ability to hold in feces (a condition known as fecal incontinence).[3][87] Rectal prolapse is relatively uncommon, however, especially in men, and its causes are not well understood.[89][90] Kegel exercises have been used to strengthen the anal sphincters and overall pelvic floor, and may help prevent or remedy fecal incontinence.[3][91]

Cancer

Most cases of anal cancer are related to infection with the human papilloma virus (HPV). Anal sex alone does not cause anal cancer; the risk of anal cancer through anal sex is attributed to HPV infection, which is often contracted through unprotected anal sex.[92] Anal cancer is relatively rare, and significantly less common than cancer of the colon or rectum (colorectal cancer); the American Cancer Society estimates that in 2023 there were approximately 9,760 new cases (6,580 in women and 3,180 in men) and approximately 1,870 deaths (860 women and 1,010 men) in the United States, and that, though anal cancer has been on the rise for many years, it is mainly diagnosed in adults, "with an average age being in the early 60s" and it "affects women somewhat more often than men."[92]

Cultural views

General

Different cultures have had different views on anal sex throughout human history, with some cultures more positive about the activity than others.[5][52][93] Historically, anal sex has been restricted or condemned, especially with regard to religious beliefs; it has also commonly been used as a form of domination, usually with the active partner (the one who is penetrating) representing masculinity and the passive partner (the one who is being penetrated) representing femininity.[5][7][52] A number of cultures have especially recorded the practice of anal sex between males, and anal sex between males has been especially stigmatized or punished.[7][57][94] In some societies, if discovered to have engaged in the practice, the individuals involved were put to death, such as by decapitation, burning, or even mutilation.[5]

Anal sex has been more accepted in modern times; it is often considered a natural, pleasurable form of sexual expression.[5][7][93] Some people, men in particular, are only interested in anal sex for sexual satisfaction, which has been partly attributed to the buttocks and anus being more eroticized in modern culture, including via pornography.[52] Engaging in anal sex is still, however, punished in some societies.[7][95] For example, regarding LGBT rights in Iran, Iran's Penal Code states in Article 109 that "both men involved in same-sex penetrative (anal) or non-penetrative sex will be punished" and "Article 110 states that those convicted of engaging in anal sex will be executed and that the manner of execution is at the discretion of the judge".[95]

Ancient and non-Western cultures

From the earliest records, the ancient Sumerians had very relaxed attitudes toward sex[96] and did not regard anal sex as taboo.[96] Entu priestesses were forbidden from producing offspring[97][98] and frequently engaged in anal sex as a method of birth control.[97][96][98] Anal sex is also obliquely alluded to by a description of an omen in which a man "keeps saying to his wife: 'Bring your backside.'"[98] Other Sumerian texts refer to homosexual anal intercourse.[96] The gala, a set of priests who worked in the temples of the goddess Inanna, where they performed elegies and lamentations, were especially known for their homosexual proclivities.[99] The Sumerian sign for gala was a ligature of the signs for 'penis' and 'anus'.[99] One Sumerian proverb reads: "When the gala wiped off his ass [he said], 'I must not arouse that which belongs to my mistress [i.e., Inanna].'"[99]

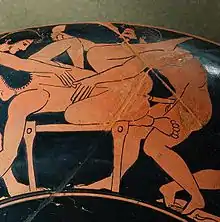

The term Greek love has long been used to refer to anal intercourse, and in modern times, "doing it the Greek way" is sometimes used as slang for anal sex.[100] Male-male anal sex was not a universally accepted practice in Ancient Greece; it was the target of jokes in some Athenian comedies.[101] Aristophanes, for instance, mockingly alludes to the practice, claiming, "Most citizens are europroktoi ('wide-arsed') now."[102] The terms kinaidos, europroktoi, and katapygon were used by Greek residents to categorize men who chronically[103] practiced passive anal intercourse.[104] Pederastic practices in ancient Greece (sexual activity between men and adolescent boys), at least in Athens and Sparta, were expected to avoid penetrative sex of any kind. Greek artwork of sexual interaction between men and boys usually depicted fondling or intercrural sex, which was not condemned for violating or feminizing boys,[105] while male-male anal intercourse was usually depicted between males of the same age-group.[106] Intercrural sex was not considered penetrative and two males engaging in it was considered a "clean" act.[101] Some sources explicitly state that anal sex between men and boys was criticized as shameful and seen as a form of hubris.[105][107] Evidence suggests, however, that the younger partner in pederastic relationships (i.e., the eromenos) did engage in receptive anal intercourse so long as no one accused him of being 'feminine'.[108]

In later Roman-era Greek poetry, anal sex became a common literary convention, represented as taking place with "eligible" youths: those who had attained the proper age but had not yet become adults. Seducing those not of proper age (for example, non-adolescent children) into the practice was considered very shameful for the adult, and having such relations with a male who was no longer adolescent was considered more shameful for the young male than for the one mounting him. Greek courtesans, or hetaerae, are said to have frequently practiced male-female anal intercourse as a means of preventing pregnancy.[109]

A male citizen taking the passive (or receptive) role in anal intercourse (paedicatio in Latin) was condemned in Rome as an act of impudicitia ('immodesty' or 'unchastity'); free men, however, could take the active role with a young male slave, known as a catamite or puer delicatus. The latter was allowed because anal intercourse was considered equivalent to vaginal intercourse in this way; men were said to "take it like a woman" (muliebria pati 'to undergo womanly things') when they were anally penetrated, but when a man performed anal sex on a woman, she was thought of as playing the boy's role.[110] Likewise, women were believed to only be capable of anal sex or other sex acts with women if they possessed an exceptionally large clitoris or a dildo.[110] The passive partner in any of these cases was always considered a woman or a boy because being the one who penetrates was characterized as the only appropriate way for an adult male citizen to engage in sexual activity, and he was therefore considered unmanly if he was the one who was penetrated; slaves could be considered "non-citizen".[110] Although Roman men often availed themselves of their own slaves or others for anal intercourse, Roman comedies and plays presented Greek settings and characters for explicit acts of anal intercourse, and this may be indicative that the Romans thought of anal sex as something specifically "Greek".[111]

In Japan, records (including detailed shunga) show that some males engaged in penetrative anal intercourse with males.[112] Evidence suggestive of widespread male-female anal intercourse in a pre-modern culture can be found in the erotic vases, or stirrup-spout pots, made by the Moche people of Peru; in a survey, of a collection of these pots, it was found that 31 percent of them depicted male-female anal intercourse significantly more than any other sex act.[113] Moche pottery of this type belonged to the world of the dead, which was believed to be a reversal of life. Therefore, the reverse of common practices was often portrayed. The Larco Museum houses an erotic gallery in which this pottery is showcased.[114]

Western cultures

In many Western countries, anal sex has generally been taboo since the Middle Ages, when heretical movements were sometimes attacked by accusations that their members practiced anal sex among themselves.[115] At that time, celibate members of the Christian clergy were accused of engaging in "sins against nature", including anal sex.[116]

The term buggery originated in medieval Europe as an insult used to describe the rumored same-sex sexual practices of the heretics from a sect originating in Bulgaria, where its followers were called bogomils;[117] when they spread out of the country, they were called buggres (from the ethnonym Bulgars).[117] Another term for the practice, more archaic, is pedicate from the Latin pedicare, with the same meaning.[118]

The Renaissance poet Pietro Aretino advocated anal sex in his Sonetti Lussuriosi ('Lust Sonnets').[119] While men who engaged in homosexual relationships were generally suspected of engaging in anal sex, many such individuals did not. Among these, in recent times, have been André Gide, who found it repulsive,[120] and Noël Coward, who had a horror of disease, and asserted when young that "I'd never do anything – well the disgusting thing they do – because I know I could get something wrong with me".[121]

During the 1980s, Margaret Thatcher questioned the inclusion of "risky sex" in the United Kingdom's AIDS related government advertisements.[122] Thatcher questioned the inclusion of the term "anal sex" in line with the Obscene Publications Act 1959. The term "rectal sex" was agreed upon to be used instead.[123]

Religion

Judaism

The Mishneh Torah, a text considered authoritative by Orthodox Jewish sects,[124] states "since a man's wife is permitted to him, he may act with her in any manner whatsoever. He may have intercourse with her whenever he so desires and kiss any organ of her body he wishes, and he may have intercourse with her naturally or unnaturally [traditionally, unnaturally refers to anal and oral sex], provided that he does not expend semen to no purpose. Nevertheless, it is an attribute of piety that a man should not act in this matter with levity and that he should sanctify himself at the time of intercourse."[125]

Christianity

Christian texts may sometimes euphemistically refer to anal sex as the peccatum contra naturam ('the sin against nature', after Thomas Aquinas) or Sodomitica luxuria ('sodomitical lusts', in one of Charlemagne's ordinances), or peccatum illud horribile, inter christianos non nominandum ('that horrible sin that among Christians is not to be named').[126][127][128]

Islam

Liwat, or the sin of Lot's people, which has come to be interpreted as referring generally to same-sex sexual activity, is commonly officially prohibited by Islamic sects; there are parts of the Quran which talk about smiting on Sodom and Gomorrah, and this is thought to be a reference to "unnatural" sex, and so there are hadith and Islamic laws which prohibit it.[129] While, concerning Islamic belief, it is objectionable to use the words al-Liwat and luti to refer to homosexuality because it is blasphemy toward the prophet of Allah, and therefore the terms sodomy and homosexuality are preferred,[130] same-sex male practitioners of anal sex are called luti or lutiyin in plural and are seen as criminals in the same way that a thief is a criminal.[130][131]

Other animals

As a form of non-reproductive sexual behavior in animals, anal sex has been observed in a few other primates, both in captivity and in the wild.[132][133][134]

See also

References

- Weiten, Wayne; Lloyd, Margaret A.; Dunn, Dana S.; Yost Hammer, Elizabeth (2016). Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st century. Cengage Learning. p. 349. ISBN 978-1305968479. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

Anal intercourse involves insertion of the penis into a partner's anus and rectum.

- See pages 270–271 for anal sex information, and page 118 for information about the clitoris. Carroll, Janell L. (2009). Sexuality Now: Embracing Diversity. Cengage Learning. pp. 629 pages. ISBN 978-0-495-60274-3. Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- Dunkin, Mary Anne. "Anal Sex Safety: What to Know". WebMD. Archived from the original on November 12, 2017. Retrieved August 19, 2013.

Often referred to simply as anal sex, anal intercourse is sexual activity that involves inserting the penis into the anus.

- Komisaruk, Barry R.; Whipple, Beverly; Nasserzadeh, Sara; Beyer-Flores, Carlos (2009). The Orgasm Answer Guide. JHU Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8018-9396-4. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- LeRoy Bullough, Vern; Bullough, Bonnie (1994). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0824079728. Archived from the original on September 17, 2020. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- McBride, Kimberly R.; Fortenberry, J. Dennis (March 2010). "Heterosexual anal sexuality and anal sex behaviors: a review". Journal of Sex Research. 47 (2–3): 123–136. doi:10.1080/00224490903402538. PMID 20358456. S2CID 37930052.

- "Anal Sex, defined". Discovery.com. Archived from the original on June 13, 2002. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- "Not all gay men have anal sex". Go Ask Alice!. June 13, 2008. Archived from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- Wellings, Kaye; Mitchell, Kirstin; Collumbien, Martine (2012). Sexual Health: A Public Health Perspective. McGraw-Hill International. p. 91. ISBN 978-0335244812. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- Newman, Felice (2004). The Whole Lesbian Sex Book: A Passionate Guide For All Of Us. Cleis Press. pp. 205–224. ISBN 978-1-57344-199-5. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- Rosenthal, Martha (2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. pp. 133–135. ISBN 978-0-618-75571-4. Archived from the original on May 20, 2016. Retrieved September 17, 2012.

- "Pain from anal sex, and how to prevent it". Go Ask Alice!. June 26, 2009. Archived from the original on August 11, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2011.

- Heidelbaugh, Joel J. (2007). Clinical men's health: evidence in practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-4160-3000-3. Archived from the original on December 19, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2011.

- Krasner, Robert I (2010). The Microbial Challenge: Science, Disease and Public Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 416–417. ISBN 978-0763797355. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- Hales, Dianne (2008). An Invitation to Health Brief 2010-2011. Cengage Learning. pp. 269–271. ISBN 978-0495391920. Retrieved August 29, 2013.

- Hoeger, Werner W. K.; Hoeger, Sharon A. (2010). Lifetime Fitness and Wellness: A Personalized Program. Cengage Learning. p. 455. ISBN 978-1133008583. Archived from the original on April 6, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- World Health Organization, Department of Reproductive Health and Research Global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections: 2006–2015. Breaking the chain of transmission Archived March 23, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, 2007, ISBN 978-92-4-156347-5

- Joann S. DeLora; Carol A. B. Warren; Carol Rinkleib Ellison (2008) [1981]. Understanding Sexual Interaction. Houghton Mifflin (Original from the University of Virginia). p. 123. ISBN 978-0-395-29724-7. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

Many men find anal intercourse more exciting than penile-vaginal intercourse because the anal opening is usually smaller and tighter than the vagina. Probably the forbidden aspect of anal intercourse also makes it more exciting for some people.

- Hunko, Celia (February 6, 2009). "Anal sex: Let's get to the bottom of this". The Daily of the University of Washington. Archived from the original on November 7, 2014. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Hawley, John C (2008). LGBTQ America Today: An Encyclopedia, Volume 1. Greenwood Press. p. 977. ISBN 978-0313339905. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- Zdrok, Victoria (2004). The Anatomy of Pleasure. Infinity Publishing. pp. 100–102. ISBN 978-0741422484. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- Gretchen M Lentz; Rogerio A. Lobo; David M Gershenson; Vern L. Katz (2012). Comprehensive Gynecology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 41. ISBN 978-0323091312. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- Michael W. Ross (1988). Psychopathology and Psychotherapy in Homosexuality. Psychology Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0866564991. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Nathaniel McConaghy (1993). Sexual Behavior: Problems and Management. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 186. ISBN 978-0306441776. Archived from the original on May 6, 2018. Retrieved March 25, 2018.

In homosexual relations, most men do not reach orgasm in receptive anal intercourse, and a number report not reaching orgasm by any method in many of their sexual relationships, which they nevertheless enjoy.

- Joseph A. Flaherty; John Marcell Davis; Philip G. Janicak (1993). Psychiatry: Diagnosis & therapy. A Lange clinical manual. Appleton & Lange (Original from Northwestern University). p. 217. ISBN 978-0-8385-1267-8.

The amount of time of sexual arousal needed to reach orgasm is variable — and usually much longer — in women than in men; thus, only 20–30% of women attain a coital climax. b. Many women (70–80%) require manual clitoral stimulation...

- Kammerer-Doak, Dorothy; Rogers, Rebecca G. (June 2008). "Female Sexual Function and Dysfunction". Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. 35 (2): 169–183. doi:10.1016/j.ogc.2008.03.006. PMID 18486835.

Most women report the inability to achieve orgasm with vaginal intercourse and require direct clitoral stimulation ... About 20% have coital climaxes...

- Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2009). Sex and Society, Volume 2. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. p. 590. ISBN 978-0-7614-7907-9. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- Kilchevsky A, Vardi Y, Lowenstein L, Gruenwald I (January 2012). "Is the Female G-Spot Truly a Distinct Anatomic Entity?". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 9 (3): 719–26. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02623.x. PMID 22240236.

- "G-Spot Does Not Exist, 'Without A Doubt,' Say Researchers". The Huffington Post. January 19, 2012. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- Wayne Weiten; Dana S. Dunn; Elizabeth Yost Hammer (2011). Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st Century. Cengage Learning. p. 386. ISBN 9781111186630. Archived from the original on June 14, 2013. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- Di Marino, Vincent (2014). Anatomic Study of the Clitoris and the Bulbo-Clitoral Organ. Springer. p. 81. ISBN 978-3319048949. Archived from the original on September 18, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- O'Connell HE, Sanjeevan KV, Hutson JM (October 2005). "Anatomy of the clitoris". The Journal of Urology. 174 (4 Pt 1): 1189–95. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd. PMID 16145367. S2CID 26109805.

- Sharon Mascall (June 11, 2006). "Time for rethink on the clitoris". BBC News. Archived from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- Yang, Claire J.; Cold, Christopher; et al. (April 2006). "Sexually responsive vascular tissue of the vulva". BJUI. 97 (4): 766–772. doi:10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05961.x. PMID 16536770. S2CID 31001005.

- Mulhall, John P.; Incrocci, Luca; Goldstein, Irwin; Rosen, Ray (2011). Cancer and Sexual Health. Springer. p. 783. ISBN 978-1-60761-915-4. Archived from the original on December 16, 2019. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- Shira Tarrant (2015). Politics: In the Streets and Between the Sheets in the 21st Century. Routledge. pp. 247–248. ISBN 978-1317814757. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- Natasha Janina Valdez (2011). Vitamin O: Why Orgasms Are Vital to a Woman's Health and Happiness, and How to Have Them Every Time!. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-61608-311-3. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- Jerrold S. Greenberg; Clint E. Bruess; Sara B. Oswalt (2014). Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 102–104. ISBN 978-1449648510. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2014.

- See page 3 Archived March 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine for women preferring anal sex to vaginal sex, and page 15 Archived March 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine for reaching orgasm through indirect stimulation of the G-spot. Tristan Taormino (1997). The Ultimate Guide to Anal Sex for Women. Cleis Press. pp. 282 pages. ISBN 978-1-57344-221-3. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- See page 560 Archived March 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine for effects of viewing pornography with regard to anal sex, and pages 286–289 Archived March 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine for anal sex as a birth control method. Robert Crooks; Karla Baur (2010–2011). Our Sexuality. Cengage Learning. pp. 570 pages. ISBN 978-0495812944. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- Flood, Michael (2010), "Young men using pornography", in Boyle, Karen (ed.), Everyday pornography, London New York: Routledge, pp. 170–171, ISBN 9780415543781. Pdf. Archived October 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine Preview. Archived March 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Thomas Johansson (2007). The Transformation of Sexuality: Gender And Identity In Contemporary Youth Culture. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 56–58. ISBN 978-1409490784. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved May 7, 2013.

- Carballo-Diéguez, Alex; Stein, Z.; Saez, H.; Dolezal, C.; Nieves-Rosa, L.; Diaz, F. (2000). "Frequent use of lubricants for anal sex among men who have sex with men". American Journal of Public Health. 90 (7): 1117–1121. doi:10.2105/AJPH.90.7.1117. PMC 1446289. PMID 10897191.

- Adrian Howe (2008). Sex, Violence and Crime: Foucault and the 'Man' Question. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 978-0203891278. Archived from the original on April 9, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- Sandra Alters; Wendy Schiff (2012). Essential Concepts for Healthy Living. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 144. ISBN 978-1449630621. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- SIECUS Prevalence of Unprotected Anal Sex among Teens Requires New Education Strategies Accessed January 26, 2010

- See here Archived August 14, 2020, at the Wayback Machine and pages 48–49 Archived December 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine for the majority of researchers and heterosexuals defining virginity loss/"technical virginity" by whether or not a person has engaged in vaginal sex. Laura M. Carpenter (2005). Virginity lost: an intimate portrait of first sexual experiences. NYU Press. pp. 295 pages. ISBN 978-0-8147-1652-6. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved October 9, 2011.

- Bryan Strong; Christine DeVault; Theodore F. Cohen (2010). The Marriage and Family Experience: Intimate Relationship in a Changing Society. Cengage Learning. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-534-62425-5. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

Most people agree that we maintain virginity as long as we refrain from sexual (vaginal) intercourse. But occasionally we hear people speak of 'technical virginity' [...] Data indicate that 'a very significant proportion of teens ha[ve] had experience with oral sex, even if they haven't had sexual intercourse, and may think of themselves as virgins' [...] Other research, especially research looking into virginity loss, reports that 35% of virgins, defined as people who have never engaged in vaginal intercourse, have nonetheless engaged in one or more other forms of heterosexual sexual activity (e.g., oral sex, anal sex, or mutual masturbation).

- Jayson, Sharon (October 19, 2005). "'Technical virginity' becomes part of teens' equation". USA Today. Archived from the original on April 28, 2011. Retrieved August 7, 2009.

- Ken Plummer (2002). Modern Homosexualities: Fragments of Lesbian and Gay Experiences. Routledge. pp. 187–191. ISBN 1134922426. Archived from the original on March 18, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

The social construction of 'sex' as vaginal intercourse affects how other forms of sexual activity are evaluated as sexually satisfying or arousing; in some cases whether an activity is seen as a sexual act at all. For example, unless a woman has been penetrated by a man's penis she is still technically a virgin even if she has had lots of sexual experience.

- Coleman, Hardin L.K.; Yeh, Christine, eds. (2011). Handbook of School Counseling. Routledge. p. 247. ISBN 978-1135283599. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- Janell L. Carroll (2012). Discovery Series: Human Sexuality (1st ed.). Cengage Learning. pp. 285–286. ISBN 978-1111841898. Archived from the original on March 5, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior (NSSHB). Archived February 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Findings from the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior, Center for Sexual Health Promotion, Indiana University. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, Vol. 7, Supplement 5. 2010.

- Steven Seidman; Nancy Fischer; Chet Meeks (2011). Introducing the New Sexuality Studies (2nd ed.). Routledge. pp. 108–112. ISBN 978-1136818103. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Edwin Clark Johnson; Toby Johnson (2008). Gay Perspective: Things Our Homosexuality Tells Us about the Nature of God & the Universe. Lethe Press. p. 139. ISBN 978-1-59021-015-4. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- Goldstone, Stephen E.; Welton, Mark L. (2004). "Sexually Transmitted Diseases of the Colon, Rectum, and Anus". Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 17 (4): 235–239. doi:10.1055/s-2004-836944. PMC 2780055. PMID 20011265.

- Steven Gregory Underwood (2003). Gay Men and Anal Eroticism: Tops, Bottoms, and Versatiles. Harrington Park Press. pp. 4–225. ISBN 978-1-56023-375-6. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- Archived October 20, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Role versatility among men who have sex with men in urban Peru. In: The Journal of Sex Research, August 2007

- Raymond A. Smith (1998). Encyclopedia of AIDS: A Social, Political, Cultural and Scientific Record of the HIV Epidemic. Taylor & Francis. pp. 73–76. ISBN 0203305493. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- "The New Sex Police". The Advocate. Here. April 12, 2005. pp. 39–40, 42. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- John H. Harvey; Amy Wenzel; Susan Sprecher (2004). The handbook of sexuality in close relationships. Routledge. pp. 355–356. ISBN 0805845488. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

- Vasquez del Aguila, Ernesto (2013). Being a Man in a Transnational World: The Masculinity and Sexuality of Migration Routledge Advances in Feminist Studies and Intersectionality. Routledge. pp. 104–105. ISBN 978-1134601882. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Joseph Gross, Michael (2003). Like a Virgin. pp. 44–45. 0001-8996. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Dolby, Tom (February 2004). "Why Some Gay Men Don't Go All The Way". Out. pp. 76–77. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 12, 2011.

- Dodge, Brian; et al. (2016). "Sexual Behaviors of U.S. Men by Self-Identified Sexual Orientation: Results From the 2012 National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior". J Sex Med. 13 (4): 637–649. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.015. PMID 26936073.

- Linda Brannon (2015). Gender: Psychological Perspectives, Sixth Edition. Psychology Press. p. 484. ISBN 978-1317348139. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

- Keesling, Barbara (2005). Sexual Pleasure: Reaching New Heights of Sexual Arousal and Intimacy. Hunter House. p. 221. ISBN 9780897934350. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- Beckett, Cooper S.; Miller, Lyndzi (October 14, 2022). The Pegging Book: A Complete Guide to Anal Sex with a Strap-On Dildo. Thorntree Press LLC. ISBN 978-1-952125-22-5.

- Iasenza, Suzanne (2020). Transforming Sexual Narratives: A Relational Approach to Sex Therapy. Routledge. p. 98. ISBN 978-0429557446. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- Janell L. Carroll (2012). Discovery Series: Human Sexuality (1st ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 285. ISBN 978-1111841898. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- Bell, Robin (February 1999). "ABC of sexual health: Homosexual men and women". BMJ. National Institutes of Health/BMJ. 318 (7181): 452–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.318.7181.452. PMC 1114912. PMID 9974466.

- JoAnn Loulan (1984). Lesbian Sex. The University of California. p. 53. ISBN 0-933216-13-0. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- Cohen, Jacqueline N.; Byers, E. Sandra (2014). "Beyond Lesbian Bed Death: Enhancing Our Understanding of the Sexuality of Sexual-Minority Women in Relationships". Journal of Sex Research. 51 (8): 893–903. doi:10.1080/00224499.2013.795924. ISSN 0022-4499. PMID 23924274. S2CID 205443248.

- Jonathan Zenilman; Mohsen Shahmanesh (2011). Sexually Transmitted Infections: Diagnosis, Management, and Treatment. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 329–330. ISBN 978-0495812944. Archived from the original on March 12, 2017. Retrieved November 4, 2012.

- Diamant AL, Lever J, Schuster M (June 2000). "Lesbians' Sexual Activities and Efforts to Reduce Risks for Sexually Transmitted Diseases". J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc. 4 (2): 41–8. doi:10.1023/A:1009513623365. S2CID 140505473.

- Partridge, Eric; Dalzell, Tom; Victor, Terry (2006). The New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English: A-I (reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-415-25937-8. Archived from the original on May 17, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

Bareback – to engage in sex without a condom.

- Donna D. Ignatavicius; M. Linda Workman (2013). Medical-Surgical Nursing: Patient-Centered Collaborative Care. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1655. ISBN 978-0323293440. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- Kumar, Bhushan; Gupta, Somesh (2014). Sexually Transmitted Infections. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 123. ISBN 978-8131229781. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- Katharine O'Connell White (2010). Talking Sex With Your Kids: Keeping Them Safe and You Sane - By Knowing What They're Really Thinking. Adams Media. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-1440506840. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Twila Pearson (2012). The Challenging Years: Shedding Light on Teen Sexuality. WestBow Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-1449773281. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- Thomas, R. Murray (2009). Sex and the American Teenager: Seeing through the Myths and Confronting the Issues. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Education. p. 81. ISBN 9781607090182. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- Edlin, Gordon (2012). Health & Wellness. Jones & Bartlett Learning. p. 213. ISBN 9781449636470. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- Dianne Hales (2014). An Invitation to Health. Cengage Learning. p. 363. ISBN 978-1305142961. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Leichliter, Jami S (2008). "Heterosexual Anal Sex: Part of an Expanding Sexual Repertoire?". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 35 (11): 910–911. doi:10.1097/olq.0b013e31818af12f. PMID 18813143. S2CID 27348658.

- M. Sara Rosenthal (2003). The Gynecological Sourcebook. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 153. ISBN 0071402799. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- Deborah Dortzbach; W. Meredith Long (2006). The AIDS Crisis: What We Can Do. InterVarsity Press. p. 97. ISBN 0830833722. Retrieved August 28, 2013.

- Nikol Hasler (2015). An Uncensored Introduction. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 91. ISBN 978-1936976843. Archived from the original on April 10, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Handbook of affirmative psychotherapy with lesbians and gay men Archived March 10, 2021, at the Wayback Machine By Kathleen Ritter, Anthony I. Terndrup; p350

- Janet R. Weber; Jane H. Kelley (2013). Health Assessment in Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 588. ISBN 978-1469832227. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- John J. Miletich; Tia Laura Lindstrom (2010). An Introduction to the Work of a Medical Examiner: From Death Scene to Autopsy Suite. ABC-CLIO. p. 29. ISBN 978-0275995089. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Donato F. Altomare; Filippo Pucciani (2008). Rectal Prolapse: Diagnosis and Clinical Management. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-8847006843. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Mark D. Walters; Mickey M. Karram (2015). Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 501. ISBN 978-0323262576. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- Hagen S, Stark D (2011). "Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12 (12): CD003882. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003882.pub4. PMID 22161382.

-

- "Detailed Guide: Anal Cancer What Are the Key Statistics About Anal Cancer?". American Cancer Society. May 2, 2014. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- "What are the risk factors for anal cancer?". American Cancer Society. May 2, 2014. Archived from the original on November 23, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- Jeffrey S. Nevid (2008). Psychology: Concepts and Applications. Cengage Learning. p. 417. ISBN 978-0547148144. Archived from the original on May 3, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

Some cultures are more permissive with respect to such sexual practices as oral sex, anal sex, and masturbation, whereas others are more restrictive.

- George Haggerty (2000–2013). Encyclopedia of Gay Histories and Cultures. Routledge. pp. 788–790. ISBN 1135585067. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- "PUBLIC AI Index: MDE 13/010/2008. UA 17/08 Fear of imminent execution/ flogging". Amnesty International. January 18, 2008. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Dening, Sarah (1996). "Chapter 3: Sex in Ancient Civilizations". The Mythology of Sex. London, England: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-02-861207-2.

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2013) [1994], Sex and Eroticism in Mesopotamian Literature, New York City, New York: Routledge, p. 219, ISBN 978-1-134-92074-7, archived from the original on April 14, 2021, retrieved January 3, 2018

- Nemet-Nejat, Karen Rhea (1998). Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood. p. 137. ISBN 978-0313294976.

- Roscoe, Will; Murray, Stephen O. (1997). Islamic Homosexualities: Culture, History, and Literature. New York City, New York: New York University Press. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-8147-7467-9. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Christie Davies (2011). Jokes and Target. Indiana University Press. pp. 155–156. ISBN 978-0253223029. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- Joan Roughgarden (2004). Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People. University of California Press. pp. 367–376. ISBN 0520240731. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Ralph Mark Rosen; Ineke Sluiter (2003). Andreia: Studies in Manliness and Courage in Classical Antiquity. Brill. p. 115. ISBN 9004119957. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Nussbaum, Martha C. (1994). "Platonic Love and Colorado Law: The Relevance of Ancient Greek Norms to Modern Sexual Controversies". Virginia Law Review. 80 (7): 1562–3. doi:10.2307/1073514. JSTOR 1073514.

the kinaidos is clearly a person who chronically plays the passive role [...] More recently, I have been convince by arguments of the late John J. Winkler that kinaidos usually connotes willingness to accept money for sex, as well as habitual passivity [...] In any case, there is no doubt that we are not dealing with an isolated act, but rather a type of person who habitually chooses activity that Callicles finds shameful. That, and no view about same-sex relations per se, is the basis of his criticism. In fact, Callicles is depicted as having a young boyfriend of his own. *The boyfriend is named Demos, also the name for the Athenian "people," to whom Callicles is also devoted. It is likely that the pun on the name is sexual: as Callicles seduces Demos, so also the demos. (It would be assumed that he would practice intercrural intercourse with this boyfriend, thus avoiding putting him in anything like the kinaidos shamed position

- Carol R. Ember; Melvin Ember (2004). Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures Topics and Cultures A-K - Volume 1; Cultures L-Z -. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 207. ISBN 030647770X. Archived from the original on May 15, 2016. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Anna Clark (2012). Desire: A History of European Sexuality. Routledge. p. 23. ISBN 978-1135762919. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Dover, Kenneth J. (1978). Greek Homosexuality. Harvard University Press. p. 99. ISBN 0674362616.

- David Cohen, "Sexuality, Violence, and the Athenian Law of Hubris" Greece and Rome; V.38.2, pp 171-188

- Dover, Kenneth J. (1978). Greek Homosexuality. Harvard University Press. p. 107. ISBN 0674362616.

- Miller, James E. (1995). "The Practices of Romans 1:26: Homosexual or Heterosexual?". Novum Testamentum. 37 (1): 9. doi:10.1163/1568536952613631.

Heterosexual anal intercourse is best illustrated in Classical vase paintings of hetaerae with their clients, and some scholars interpret this as a form of contraception

- Marilyn B. Skinner (1997). Invading the Roman Body: Manliness and Impenetrability in Roman Thought. Roman Sexualities. Princeton University Press. pp. 14–31. ISBN 0-691-01178-8. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2012.

- Thomas K. Hubbard (2003). Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents. University of California Press. p. 309. ISBN 0520234308. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Gary P. Leupp (1997). Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan. University of California Press. p. 122. ISBN 052091919X. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Reay Tannahill (1989). Sex In History. Abacus Books. pp. 297–298. ISBN 0349104867. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- "Larco Museum - Lima Peru - Experience Ancient Peru - Permanent Exhibition". Museolarco.org. Archived from the original on March 4, 2013. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- Herbenick, Debby. Good in Bed Guide to Anal Pleasuring. Good in Bed Guides. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-9843221-6-9.

- Robert Aldrich; Garry Wotherspoo (2002). Who's Who in Gay and Lesbian History Vol.1: From Antiquity to the Mid-Twentieth Century. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 020398675X. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Erin McKean, ed. (2005). New Oxford American Dictionary, 2nd edition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517077-6.

- Pollini, John (March 1999). "The Warren Cup: Homoerotic Love and Symposial Rhetoric in Silver". The Art Bulletin. 81 (1): 21–52. doi:10.2307/3051285. JSTOR 3051285.

"I have derived the word pedicate from the Latin paedicare or pedicare, meaning "to penetrate anally." Note 6.

- Daileader, Celia R. (Summer 2002). "Back Door Sex: Renaissance Gynosodomy, Aretino, and the Exotic" (PDF). English Literary History. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 69 (2): 303–334. doi:10.1353/elh.2002.0012. S2CID 161498585. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2007. Retrieved April 30, 2007.

- Kevin Kopelson (1994). Love's Litany: The Writing of Modern Homoerotics. Stanford University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0804723451. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Philip Hoare (1998). Noël Coward: A Biography. University of Chicago Press. p. 18. ISBN 0226345122. Retrieved December 22, 2013.

- Low, Valentine (December 30, 2015). "Squeamish Thatcher tried to tone down language of Aids ads". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2022. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- Jaspal, Rusi; Bayley, Jake (October 29, 2020). HIV and Gay Men: Clinical, Social and Psychological Aspects. Springer Nature. p. 34. ISBN 978-981-15-7226-5. Retrieved April 24, 2022.

- Isidore Twersky, Introduction to the Code of Maimonides (Mishneh Torah), Yale Judaica Series, vol. XII (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1980). passim, and especially Chapter VII, "Epilogue", pp. 515–538.

- Maimonides, Moshe. Mishneh Torah. p. Laws Concerning Forbidden Relations 21:9.

- Albrecht Classen (2010). Sexuality in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times: New Approaches to a Fundamental Cultural-historical and Literary-anthropological Theme. Walter de Gruyter. p. 13. ISBN 978-3110205749. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Byrne Fone (2001). Homophobia: A History. Macmillan. p. 133. ISBN 1466817070. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Louis Crompton (2009). Homosexuality and Civilization. Harvard University Press. p. 529. ISBN 978-0674030060. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Mark M Leach (2014). Cultural Diversity and Suicide: Ethnic, Religious, Gender, and Sexual Orientation Perspectives. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 978-1317786597. Archived from the original on March 26, 2015. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Yahaya Yunusa Bambale (2008) [2003]. Crimes and Punishments Under Islamic Law. Malthouse Press Limited. p. 40. ISBN 978-9780231590. Archived from the original on March 10, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

- Randy P. Conner; David Hatfield Sparks; Mariya Sparks (2006) [1997]. Cassell's Encyclopedia of Queer Myth, Symbol, and Spirit: Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender Lore. Cassell. pp. 20, 216. ISBN 0304337609. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved September 15, 2014.

Indeed, homoeroticism in general and anal intercourse in particular are referred to as liwat, while those (primarily men) engaging in these behaviors are referred to as qaum Lut or Luti, 'the people of Lot.'

- Erwin J.; Maple T (1976). "Ambisexual behavior with male-male anal insertion in male rhesus monkeys". Archives of Sexual Behavior. 5 (1): 9–14. doi:10.1007/bf01542236. PMID 816329. S2CID 46074855.

- Busia, L; Denice, AR; Aureli, F; Schaffner, CM (May 2018). "Homosexual behavior between male spider monkeys (Ateles geoffroyi)" (PDF). Archives of Sexual Behavior. 47 (4): 857–861. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1177-8. PMID 29536259. S2CID 3855790. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 11, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2021.

- Fang, Gu; Dixson, Alan F.; Qi, Xiao-Guang; Li, Bao-Guo (April 2018). "Male-Male Mounting Behaviour in Free-Ranging Golden Snub-Nosed Monkeys (Rhinopithecus roxellana)". Folia Primatologica. Karger Publishers. 89 (2): 150–156. doi:10.1159/000487004. PMID 29621754. S2CID 4597770. Archived from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

Further reading

- Brent, Bill Ultimate Guide to Anal Sex for Men, Cleis Press, 2002.

- DeCitore, David Arouse Her Anal Ecstasy (2008) ISBN 978-0-615-39914-0

- Houser, Ward Anal Sex, Encyclopedia of Homosexuality Dynes, Wayne R. (ed.), Garland Publishing, 1990. pp. 48–50.

- Morin, Jack Anal Pleasure & Health: A Guide for Men and Women, Down There Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-940208-20-9

- Sanderson, Terry The Gay Man's Kama Sutra, Thomas Dunne Books, 2004.

- Tristan Taormino The Ultimate Guide to Anal Sex for Women, Cleis Press, 1997, 2006. ISBN 978-1-57344-028-8

- Underwood, Steven G. Gay Men and Anal Eroticism: Tops, Bottoms, and Versatiles, Harrington Park Press, 2003