Analytical psychology

Analytical psychology (German: Analytische Psychologie, sometimes translated as analytic psychology and referred to as Jungian analysis) is a term coined by Carl Jung, a Swiss psychiatrist, to describe research into his new "empirical science" of the psyche. It was designed to distinguish it from Freud's psychoanalytic theories as their seven-year collaboration on psychoanalysis was drawing to an end between 1912 and 1913.[1][2][3] The evolution of his science is contained in his monumental opus, the Collected Works, written over sixty years of his lifetime.[4]

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Psychoanalysis |

|---|

.jpeg.webp) |

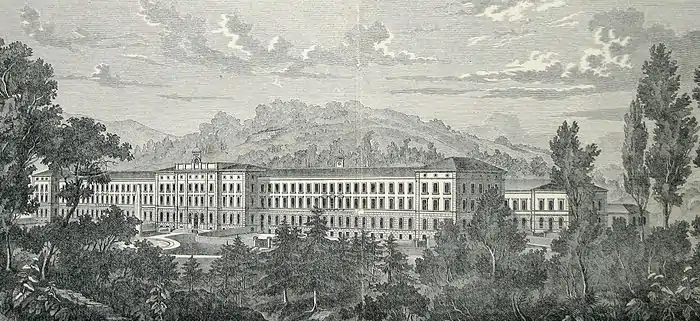

The history of analytical psychology is intimately linked with the biography of Jung. At the start, it was known as the "Zurich school", whose chief figures were Eugen Bleuler, Franz Riklin, Alphonse Maeder and Jung, all centred in the Burghölzli hospital in Zurich. It was initially a theory concerning psychological complexes until Jung, upon breaking with Sigmund Freud, turned it into a generalised method of investigating archetypes and the unconscious, as well as into a specialised psychotherapy.

Analytical psychology, or "complex psychology", from the German: Komplexe Psychologie, is the foundation of many developments in the study and practice of Psychology as of other disciplines. Jung has many followers, and some of them are members of national societies around the world. They collaborate professionally on an international level through the International Association of Analytical Psychologists (IAAP) and the International Association for Jungian Studies (IAJS). Jung's propositions have given rise to a multidisciplinary literature in numerous languages.

Among widely used concepts specific to analytical psychology are anima and animus, archetypes, the collective unconscious, complexes, extraversion and introversion, individuation, the Self, the shadow and synchronicity.[5][6] The Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is based on another of Jung's theories on psychological types.[5][7][8] A lesser known idea was Jung's notion of the Psychoid to denote a hypothesised immanent plane beyond consciousness, distinct from the collective unconscious, and a potential locus of synchronicity.[9]

The approximately "three schools" of post-Jungian analytical psychology that are current, the classical, archetypal and developmental, can be said to correspond to the developing yet overlapping aspects of Jung's lifelong explorations, even if he expressly did not want to start a school of "Jungians".[5](pp. 50–53)[10] Hence as Jung proceeded from a clinical practice which was mainly traditionally science-based and steeped in rationalist philosophy, anthropology and ethnography, his enquiring mind simultaneously took him into more esoteric spheres such as alchemy, astrology, gnosticism, metaphysics, myth and the paranormal, without ever abandoning his allegiance to science as his long-lasting collaboration with Wolfgang Pauli attests.[11] His wide-ranging progression suggests to some commentators that, over time, his analytical psychotherapy, informed by his intuition and teleological investigations, became more of an "art".[5]

The findings of Jungian analysis and the application of analytical psychology to contemporary preoccupations such as social and family relationships,[12] dreams and nightmares, work–life balance,[13] architecture and urban planning,[14] politics and economics, conflict and warfare,[15] and climate change are illustrated in several publications and films.[16][17][18][19]

Origins

Jung began his career as a psychiatrist in Zürich, Switzerland. Already employed at the Burghölzli hospital in 1901, in his academic dissertation for the medical faculty of the University of Zurich he took the risk of using his experiments on somnambulism and the visions of his mediumistic cousin, Helly Preiswerk. The work was entitled, "On the Psychology and Pathology of So-Called Occult Phenomena".[20] It was accepted but caused great upset among his mother's family.[21] Under the direction of psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler, he also conducted research with his colleagues using a galvanometer to evaluate the emotional sensitivities of patients to lists of words during word association.[21][22][23][24] Jung has left a description of his use of the device in treatment.[25][26][27] His research earned him a worldwide reputation and numerous honours, including honorary Doctorates from Clark and Fordham Universities in 1909 and 1910 respectively. Other honours followed later.[28][29]

Although they began corresponding a year earlier, in 1907 Jung travelled to meet Sigmund Freud in Vienna, Austria. At that stage, Jung, aged thirty-two, had a much greater international renown than the forty-nine-year-old neurologist.[21] For a further six years, the two scholars worked and travelled to the United States together. In 1911, they founded the International Psychoanalytical Association, of which Jung was the first president.[21] However, early in the collaboration, Jung had already observed that Freud would not tolerate ideas that were different from his own.[21]

Unlike most modern psychologists, Jung did not believe in restricting himself to the scientific method as a means to understanding the human psyche. He saw dreams, myths, coincidence, and folklore as empirical evidence to further understanding and meaning. So although the unconscious cannot be studied by using direct methods, it acts as a useful working hypothesis, according to Jung.[30] As he said, "The beauty about the unconscious is that it is really unconscious."[31] Hence, the unconscious is 'untouchable' by experimental researches, or indeed any possible kind of scientific or philosophical reach, precisely because it is unconscious.[32][33]

The break with Freud

It was the publication of a book by Jung which provoked the break with psychoanalysis and led to the founding of analytical psychology. In 1912 Jung met "Miss Miller", brought to his notice by the work of Théodore Flournoy and whose case gave further substance to his theory of the collective unconscious.[34]: 213–215 The study of her visions supplied the material which would go on to furnish his reasoning which he developed in Psychology of the Unconscious (Wandlungen und Symbole der Libido) (re-published as Symbols of Transformation in 1952) (C.W. Vol. 5). At this, Freud muttered about "heresy".[35] It was the second part of the work that brought the divergence to light. Freud mentioned to Ernest Jones that it was on page 174 of the original German edition, that Jung, according to him, had "lost his way".[34]: 215 It is the extract where Jung enlarged on his conception of the libido. The sanction was immediate: Jung was officially banned from the Vienna psychoanalytic circle from August 1912. From that date the psychoanalytic movement split into two obediences, with Freud's partisans on one side, Karl Abraham being delegated to write a critical notice about Jung,[36] and with Ernest Jones as defender of Freudian orthodoxy; while on the other side, were Jung's partisans, including Leonhard Seif, Franz Riklin, Johan van Ophuijsen and Alphonse Maeder.[34]: 260

Jung's innovative ideas with a new formulation of psychology and lack of contrition sealed the end of the Jung-Freud friendship in 1913. From then, the two scholars worked independently on personality development: Jung had already termed his approach analytical psychology (1912), while the approach Freud had founded is referred to as the Psychoanalytic School, (psychoanalytische Schule).[1]

%252C_page_5.jpg.webp)

Jung's postulated unconscious was quite different from the model proposed by Freud, despite the great influence that the founder of psychoanalysis had had on him. In particular, tensions manifested between him and Freud because of various disagreements, including those concerning the nature of the libido.[37] Jung de-emphasized the importance of sexual development as an instinctual drive and focused on the collective unconscious: the part of the unconscious that contains memories and ideas which Jung believed were inherited from generations of ancestors. While he accepted that libido was an important source for personal growth, unlike Freud, Jung did not consider that libido alone was responsible for the formation of the core personality.[38] Due to the particular hardships Jung had endured growing up, he believed his personal development and that of everyone was influenced by factors unrelated to sexuality.[37]

The overarching aim in life, according to Jungian psychology, is the fullest possible actualisation of the "Self" through individuation.[39][6] Jung defines the "self" as "not only the centre but also the whole circumference which embraces both conscious and unconscious; it is the centre of this totality, just as the ego is the centre of the conscious mind".[40] Central to this process of individuation is the individual's continual encounter with the elements of the psyche by bringing them into consciousness.[6] People experience the unconscious through symbols encountered in all aspects of life: in dreams, art, religion, and the symbolic dramas enacted in relationships and life pursuits.[6] Essential to the process is the merging of the individual's consciousness with the collective unconscious through a huge range of symbols. By bringing conscious awareness to bear on what is unconscious, such elements can be integrated with consciousness when they "surface".[6] To proceed with the individuation process, individuals need to be open to the parts of themselves beyond their own ego, which is the "organ" of consciousness.[6] In a famous dictum, Jung said, "the Self, like the unconscious is an a priori existent out of which the ego evolves. It is ... an unconscious prefiguration of the ego. It is not I who create myself, rather I happen to myself'.[41]

It follows that the aim of (Jungian) psychotherapy is to assist the individual to establish a healthy relationship with the unconscious so that it is neither excessively out of balance in relation to it, as in neurosis, a state that can result in depression, anxiety, and personality disorders or so flooded by it that it risks psychosis resulting in mental breakdown. One method Jung applied to his patients between 1913 and 1916 was active imagination, a way of encouraging them to give themselves over to a form of meditation to release apparently random images from the mind to bridge unconscious contents into awareness.[42]

"Neurosis" in Jung's view results from the build up of psychological defences the individual unconsciously musters in an effort to cope with perceived attacks from the outside world, a process he called a "complex", although complexes are not merely defensive in character.[6] The psyche is a self-regulating adaptive system.[6] People are energetic systems, and if the energy is blocked, the psyche becomes sick. If adaptation is thwarted, the psychic energy stops flowing and becomes rigid. This process manifests in neurosis and psychosis. Jung proposed that this occurs through maladaptation of one's internal realities to external ones. The principles of adaptation, projection, and compensation are central processes in Jung's view of psyche's attempts to adapt.

Innovations of Jungian analysis

Philosophical and epistemological foundations

Philosophy

Jung was an adept principally of the American philosopher William James, founder of pragmatism, whom he met during his trip to the United States in 1909.[21]: 255 He also encountered other figures associated with James, such as John Dewey and the anthropologist, Franz Boas.[21]: 165 Pragmatism was Jung's favoured route to base his psychology on a sound scientific basis according to historian Sonu Shamdasani.[43] His theories consist of observations of phenomena, and according to Jung it is phenomenology. In his view psychologism was suspect.[37]

Displacement into the conceptual deprives experience of its substance and the possibility of being simply named.

Throughout his writings, Jung sees in empirical observation not only a precondition of an objective method but also respect for an ethical code which should guide the psychologist, as he stated in a letter to Joseph Goldbrunner:

I consider it a moral obligation not to make assertions about things one cannot see or whose existence cannot be proved, and I consider it an abuse of epistemological power to do so regardless. These rules apply to all experimental science. Other rules apply to metaphysics. I regard myself as answerable to the rules of experimental science. As a result nowhere in my work are there any metaphysical assertions nor – nota bene – any negations of a metaphysical nature.[44]

According to the Italo-French psychoanalyst Luigi Aurigemma, Jung's reasoning is also marked by Immanuel Kant, and more generally by German rationalist philosophy. His lectures are evidence of his assimilation of Kantian thought, especially the Critique of Pure Reason and Critique of Practical Reason.[45] Aurigemma characterises Jung's thinking as "epistemological relativism" because it does not postulate any belief in the metaphysical.[45]: 19 In fact, Jung uses Kant's teleology to bridle his thinking and to guard himself from straying into any metaphysical excursions.[45]: 21 On the other hand, for French historian of psychology, Françoise Parot, contrary to the alleged rationalist vein, Jung is "heir" to mystics, (Meister Eckhart, Hildegard of Bingen, or Augustine of Hippo,[45]: 96 ) and to the romantics be they scientists, such as Carl Gustav Carus or Gotthilf Heinrich von Schubert in particular, or to philosophers and writers, along the lines of Nietzsche, Goethe, and Schopenhauer, in the way he conceptualised the unconscious in particular. Whereas his typology is profoundly dependent on Carl Spitteler.[21]: 255

Scientific heritage

As a trained psychiatrist, Jung had a grounding in the state of science in his day. He regularly refers to the experimental psychology of Wilhelm Wundt. His Word Association Test designed with Franz Riklin is actually the direct application of Wundt's theory. Notwithstanding the great debt of analytical psychology to Sigmund Freud, Jung borrowed concepts from other theories of his time. For instance, the expression "abaissement du niveau mental" comes directly from the French psychologist Pierre Janet whose courses Jung attended during his studies in France, during 1901. Jung had always acknowledged how much Janet had influenced his career.

Jung's use of the concept of "participation mystique" is owed to the French ethnologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl:

What Rousseau describes is nothing other than the primitive collective mentality which Lucien Lévy-Bruhl has brilliantly called "participation mystique",[46]

which he uses to illustrate the surprising fact, to him, that some native peoples can experience relations that defy logic, as for instance in the case of the South American tribe, whom he met during his travels, where the men pretended they were scarlet aras birds. Finally, his use of the English expression, "pattern of behaviour", which is synonymous with the term archetype, is drawn from British studies in ethology.

The principal contribution to analytical psychology, nevertheless, remains that of Freud's psychoanalysis, from which Jung took a number of concepts, especially the method of inquiring into the unconscious through free association. Individual analysts' thinking was also integrated into his project, among whom are Sándor Ferenczi (Jung refers to his notion of "affect") or Ludwig Binswanger and his Daseinsanalyse , (Daseinsanalysis). Jung affirms also Freud's contribution to our knowledge of the psyche as being, without doubt, of the highest importance. It reveals penetrating information about the dark corners of the soul and of the human personality, which is of the same order as Nietzsche's On the Genealogy of Morality (1887). In this context, Freud was, according to Jung, one of the great cultural critics of the 19th century.[47]

Divergences from psychoanalysis

Jungian Analysis, as is psychoanalysis, is a method to access, experience and integrate unconscious material into awareness. It is a search for the meaning of behaviours, feelings and events. Many are the channels to extend knowledge of the self: the analysis of dreams is one important avenue. Others may include expressing feelings about and through art, poetry or other expressions of creativity, the examination of conflicts and repeating patterns in a person's life. A comprehensive description of the process of dream interpretation is complex, in that it is highly specific to the person who undertakes it. Most succinctly it relies on the associations which the particular dream symbols suggest to the dreamer, which at times may be deemed "archetypal" in so far as they are supposed common to many people throughout history. Examples could be a hero, an old man or woman, situations of pursuit, flying or falling.

Whereas (Freudian) psychoanalysis relies entirely on the development of the transference in the analysand (the person under treatment) to the analyst, Jung initially used the transference and later concentrated more on a dialectical and didactic approach to the symbolic and archetypal material presented by the patient. Moreover, his attitude towards patients departed from what he had observed in Freud's method. Anthony Stevens has explained it thus:

- Though [Jung's] initial formulations arose mainly out of his own creative illness,[48][49] they were also a conscious reaction against the stereotype of the classical Freudian analyst, sitting silent and aloof behind the couch, occasionally emitting ex cathedra pronouncements and interpretations, while remaining totally uninvolved in the patient's guilt, anguish, and need for reassurance and support. Instead, Jung offered the radical proposal that analysis is a dialectical procedure, a two-way exchange between two people, who are equally involved. Although it was a revolutionary idea when he first suggested it, it is a model which has influenced psychotherapists of most schools, though many seem not to realise that it originated with Jung.[50]

In place of Freud's "surgical detachment", Jung demonstrated a more relaxed and warmer welcome in the consulting room.[50] He remained aware nonetheless that exposure to a patient's unconscious contents always posed a certain risk of contagion (he calls it "psychic infection") to the analyst, as experienced in the countertransference.[51] The process of contemporary Jungian analysis depends on the type of "school of analytical psychology" to which the therapist adheres, (see below). The "Zurich School" would reflect the approach Jung himself taught, while those influenced by Michael Fordham and associates in London, would be significantly closer to a Kleinian approach and therefore, concerned with analysis of the transference and countertransference as indicators of repressed material along with the attendant symbols and patterns.[52]

Dream work

Jung's preoccupation with dreams can be dated from 1902.[53] It was only after the break with Freud that he published in 1916 his "Psychology of the Unconscious" where he elaborated his view of dreams, which contrasts sharply with Freud's conceptualisation.[54] While he agrees that dreams are a highway into the unconscious, he enlarges on their functions further than psychoanalysis did. One of the salient differences is the compensatory function they perform by reinstating psychic equilibrium in respect of judgments made during waking life: thus a man consumed by ambition and arrogance may, for example, dream about himself as small and vulnerable person.[55][56]

According to Jung, this demonstrates that the man's attitude is excessively self-assured and thereby refuses to integrate the inferior aspects of his personality, which are denied by his defensive arrogance. Jung calls this a compensation mechanism, necessary for the maintenance of a healthy mental balance. Shortly before his death in 1961, he wrote:

To secure mental and even physiological stability, it is necessary that the conscious and unconscious should be integrated one with the other. This is so that they evolve in parallel. (Pour sauvegarder la stabilité mentale, et même physiologique, il faut que la conscience et l'inconscient soient intégralement reliés, afin d'évoluer parallèlement)[57]

Unconscious material is expressed in images through the deployment of symbolism which, in Jungian terms, means it has an affective role (in that it can sometimes give rise to a numinous feeling, when associated with an archetypal force) and an intellectual role.[58] Some dreams are personal to the dreamer, others may be collective in origin or "transpersonal" in so far as they relate to existential events.[59] They can be taken to express phases of the individuation process (see below) and may be inspired by literature, art, alchemy or mythology. Analytical psychology is recognized for its historical and geographical study of myths as a means to deconstruct, with the aid of symbols, the unconscious manifestations of the psyche. Myths are said to represent directly the elements and phenomena arising from the collective unconscious and though they may be subject to alteration in their detail through time, their significance remains similar. While Jung relies predominantly on Christian or on Western pagan mythology (Ancient Greece and Rome), he holds that the unconscious is driven by mythologies derived from all cultures. He evinced an interest in Hinduism, in Zoroastrianism and Taoism, which all share fundamental images reflected in the psyche. Thus analytical psychology focusses on meaning, based on the hypothesis that human beings are potentially in constant touch with universal and symbolic aspects common to humankind. In the words of André Nataf:

Jung opens psychoanalysis to a dimension currently obscured by the prevailing scientism: spirituality. His contribution, though questionable in certain respects, remains unique. His explorations of the unconscious carried out both as a scientist and a poet, indicate that it is structured as a language but one which is in a mythical mode. (Jung ouvre la psychanalyse à une dimension cachée par le scientisme ambiant : la spiritualité. Son apport, quoique contestable sur certains points, reste unique. Explorant l'inconscient en scientifique et poète, il montre que celui-ci se structure non-comme une langue mais sur le mode du mythe)[60]

Principal concepts

In analytical psychology two distinct types of psychological process may be identified: that deriving from the individual, characterised as "personal", belonging to a subjective psyche, and that deriving from the collective, linked to the structure of an objective psyche, which may be termed "transpersonal".[61] These processes are both said to be archetypal. Some of these processes are regarded as specifically linked to consciousness, such as the animus or anima, the persona or the shadow. Others pertain more to the collective sphere. Jung tended to personify the anima and animus as they are, according to him, always attached to a person and represent an aspect of his or her psyche.[61]

Anima and animus

Jung identified the archetypal anima as being the unconscious feminine component of men and the archetypal animus as the unconscious masculine component in women.[62] These are shaped by the contents of the collective unconscious, by others, and by the larger society.[62] However, many modern-day Jungian practitioners do not ascribe to a literal definition, citing that the Jungian concept points to every person having both an anima and an animus.[63] Jung considered, for instance, an "animus of the anima" in men, in his work Aion and in an interview in which he says:

Yes, if a man realizes the animus of his anima, then the animus is a substitute for the old wise man. You see, his ego is in relation to the unconscious, and the unconscious is personified by a female figure, the anima. But in the unconscious is also a masculine figure, the wise old man. And that figure is in connection with the anima as her animus, because she is a woman. So, one could say the wise old man was in exactly the same position as the animus to a woman.[64]

Jung stated that the anima and animus act as guides to the unconscious unified Self, and that forming an awareness and a connection with the anima or animus is one of the most difficult and rewarding steps in psychological growth. Jung reported that he identified his anima as she spoke to him, as an inner voice, unexpectedly one day.

In cases where the anima or animus complexes are ignored, they vie for attention by projecting itself on others.[65] This explains, according to Jung, why we are sometimes immediately attracted to certain strangers: we see our anima or animus in them. Love at first sight is an example of anima and animus projection. Moreover, people who strongly identify with their gender role (e.g. a man who acts aggressively and never cries) have not actively recognized or engaged their anima or animus.

Jung attributes human rational thought to be the male nature, while the irrational aspect is considered to be natural female (rational being defined as involving judgment, irrational being defined as involving perceptions). Consequently, irrational moods are the progenies of the male anima shadow and irrational opinions of the female animus shadow.

Archetypes

The use of archetypes in psychology was advanced by Jung in an essay entitled "Instinct and the Unconscious" in 1919.[42] The first element in Greek 'arche' signifies 'beginning, origin, cause, primal source principle', by extension it can signify 'position of a leader, supreme rule and government'. The second element 'type' means 'blow or what is produced by a blow, the imprint of a coin ...form, image, prototype, model, order, and norm', ...in the figurative, modern sense, 'pattern underlying form, primordial form'.[66] In his psychological framework, archetypes are innate, universal or personal prototypes for ideas and may be used to interpret observations. The method he favoured was hermeneutics which was central in his practice of psychology from the start. He made explicit references to hermeneutics in the Collected Works and during his theoretical development of the notion of archetypes. Although he lacks consistency in his formulations, his theoretical development of archetypes is rich in hermeneutic implications. As noted by Smythe and Baydala (2012),

his notion of the archetype as such can be understood hermeneutically as a form of non-conceptual background understanding.[67]

A group of memories and attitudes associated with an archetype can become a complex, e.g. a mother complex may be associated with a particular mother archetype. Jung treated the archetypes as psychological organs, analogous to physical ones in that both are morphological givens which probably arose through evolution.

Archetypes have been regarded as collective as well as individual, and identifiable in a variety of creative ways. As an example, in his book Memories, Dreams, Reflections, Jung states that he began to see and talk to a manifestation of anima and that she taught him how to interpret dreams. As soon as he could interpret on his own, Jung said that she ceased talking to him because she was no longer needed.[68] However, the essentialism inherent in archetypal theory in general and concerning the anima, in particular, has called for a re‐evaluation of Jung's theory in terms of emergence theory. This would emphasise the role of symbols in the construction of affect in the midst of collective human action. In such a reconfiguration, the visceral energy of a numinous experience can be retained while the problematic theory of archetypes has outlived its usefulness.[69]

Collective unconscious

Jung's concept of the collective unconscious has undergone re-interpretation over time. The term "collective unconscious" first appeared in Jung's 1916 essay, "The Structure of the Unconscious".[70] This essay distinguishes between the "personal", Freudian unconscious, filled with fantasies (e. g. sexual) and repressed images, and the "collective" unconscious encompassing the soul of humanity at large.[71]

In "The Significance of Constitution and Heredity in Psychology" (November 1929), Jung wrote:

And the essential thing, psychologically, is that in dreams, fantasies, and other exceptional states of mind the most far-fetched mythological motifs and symbols can appear autochthonously at any time, often, apparently, as the result of particular influences, traditions, and excitations working on the individual, but more often without any sign of them. These "primordial images" or "archetypes," as I have called them, belong to the basic stock of the unconscious psyche and cannot be explained as personal acquisitions. Together they make up that psychic stratum which has been called the collective unconscious. The existence of the collective unconscious means that individual consciousness is anything but a tabula rasa and is not immune to predetermining influences. On the contrary, it is in the highest degree influenced by inherited presuppositions, quite apart from the unavoidable influences exerted upon it by the environment. The collective unconscious comprises in itself the psychic life of our ancestors right back to the earliest beginnings. It is the matrix of all conscious psychic occurrences, and hence it exerts an influence that compromises the freedom of consciousness in the highest degree, since it is continually striving to lead all conscious processes back into the old paths.[72]

Given that in his day he lacked the advances of complexity theory and especially complex adaptive systems (CAS), it has been argued that his vision of archetypes as a stratum in the collective unconscious, corresponds to nodal patterns in the collective unconscious which go on to shape the characteristic patterns of human imagination and experience and in that sense, "seems a remarkable, intuitive articulation of the CAS model".[73]

Individuation

Individuation is a complex process that involves going through different stages of growing awareness through the progressive confrontation and integration of personal unconscious elements. This is the central concept of analytical psychology first introduced in 1916.[74][75] It is the objective of Jungian psychotherapy to the extent that it enables the realisation of the Self.[76] As Jung stated:

The aim of individuation is nothing less than to divest the self of the false wrappings of the persona, on the one hand and the suggestive power of primordial images on the other.[77]

Jung started experimenting with individuation after his split with Freud as he confronted what was described as eruptions from the collective unconscious driven by a contemporary malaise of spiritual alienation.[78] According to Jung, individuation means becoming an individual and implies becoming one's own self.[79] Unlike individuality, which emphasizes some supposed peculiarity, Jung described individuation as a better and more complete fulfillment of the collective qualities of the human being.[79] In his experience, Jung explained that individuation helped him, "from the therapeutic point of view, to find the particular images that lie behind emotions".[78]

Individuation is from the first what the analysand must undergo, to integrate the other elements of the psyche.[45]: 35 This pursuit of wholeness aims to establish the Self, which include both the rational conscious mind of the ego and the irrational contents of the unconscious, as the new personality center.[80] Prior to individuation, the analysand is carefully assessed to determine if the ego is strong enough to take the intensity of this process.[81] The elements to be integrated include the persona which acts as the representative of the person in her/his role in society, the shadow which contains all that is personally unknown and what the person considers morally reprehensible and, the anima or the animus, which respectively carry their feminine and masculine values.[82] For Jung many unconscious conflicts at the root of neurosis are caused by the difficulty to accept that such a dynamic can unbalance the subject from his habitual position and confronts her/him with aspects of the self they were accustomed to ignore. Once individuation is completed the ego is no longer at the centre of the personality.[83] The process, however, does not lead to a complete self-realization and that individuation can never be a fixed state due to the unfathomable nature of the depths of the collective unconscious.[84]

Shadow

The shadow is an unconscious complex defined as the repressed, suppressed or disowned qualities of the conscious self.[85] According to Jung, the human being deals with the reality of the shadow in four ways: denial, projection, integration and/or transmutation. Jung himself asserted that "the result of the Freudian method of elucidation is a minute elaboration of man's shadow-side unexampled in any previous age."[86]: 63 According to analytical psychology, a person's shadow may have both constructive and destructive aspects. In its more destructive aspects, the shadow can represent those things people do not accept about themselves. For instance, the shadow of someone who identifies as being kind may be harsh or unkind. Conversely, the shadow of a person who perceives himself to be brutal may be gentle. In its more constructive aspects, a person's shadow may represent hidden positive qualities. This has been referred to as the "gold in the shadow". Jung emphasized the importance of being aware of shadow material and incorporating it into conscious awareness to avoid projecting shadow qualities on others.

The shadow in dreams is often represented by dark figures of the same gender as the dreamer.[87]

The shadow may also concern great figures in the history of human thought or even spiritual masters, who became great because of their shadows or because of their ability to live their shadows (namely, their unconscious faults) in full without repressing them.

Persona

Just like the anima and animus, the persona (derived from the Latin term for a mask, as would have been worn by actors) is another key concept in analytical psychology. It is the part of the personality which manages an individual's relations with society in the outside world and works the same way for both sexes.[88]

The persona ... is the individual's system of adaptation to, or the manner assumed in dealing with the world. Every calling or profession, for example, has its own characteristic persona [...] Only the danger is that (people) become identical with their personas: thus the professor with his textbook, the tenor with his voice. One could say with little exaggeration, that the persona is that which in reality one is not, but which oneself as well as others think one is.[37]: 415–416

The persona, which is at the heart of the psyche, is contrary to the shadow which is actually the true personality but denied by the self. The conscious self identifies primarily with the persona during development in childhood as the individual develops a psychological framework for dealing with others.[89] Identifications with diplomas, social roles, with honours and awards, with a career, all contribute to the apparent constitution of the persona and which do not lead to knowledge of the self. For Jung, the persona has nothing real about it.[90] It can only be a compromise between the individual and society, yielding an illusion of individuality.[91] Individuation consists, in the first instance, of discarding the individual's mask, but not too quickly as often, it is all the patient has as a means of identification.[92] The persona is implicated in a number of symptoms such as compulsive disorders, phobias, shifting moods, and addictions, among others.[93]

Psychological types

Analytical psychology distinguishes several psychological types or temperaments.

According to Jung, the psyche is an apparatus for adaptation and orientation, and consists of a number of different psychic functions. Among these he distinguishes four basic functions:[94]

- Sensation – Perception by means of the sense organs

- Intuition – Perceiving in unconscious way or perception of unconscious contents

- Thinking – Function of intellectual cognition; the forming of logical conclusions

- Feeling – Function of subjective estimation

Complexes

Early in Jung's career he coined the term and described the concept of the "complex". Jung claims to have discovered the concept during his free association and galvanic skin response experiments. Freud obviously took up this concept in his Oedipus complex amongst others. Jung seemed to see complexes as quite autonomous parts of psychological life. It is almost as if Jung were describing separate personalities within what is considered a single individual, but to equate Jung's use of complexes with something along the lines of multiple personality disorder would be a step out of bounds.

Jung saw an archetype as always being the central organizing structure of a complex. For instance, in a "negative mother complex", the archetype of the "negative mother" would be seen to be central to the identity of that complex. This is to say, our psychological lives are patterned on common human experiences. Jung saw the Ego (which Freud wrote about in German literally as the "I", one's conscious experience of oneself) as a complex. If the "I" is a complex, what might be the archetype that structures it? Jung, and many Jungians, might say "the hero", one who separates from the community to ultimately carry the community further.

Synchronicity

Jung first officially used the term synchronicity during a conference held in memory of his sinologist friend, Richard Wilhelm in 1930.[95] It was part of his explanation of the modus operandi of the I Ching.[95] The second reference was made in 1935 in his Tavistock Lectures.

For an overview of the origins of the concept, see Joseph Cambray: "Synchronicity as emergence".[96] It was used to denote the simultaneous occurrence of two events with no causal physical connection, but whose association evokes a meaning for the person experiencing or observing it. The often cited example of the phenomenon is Jung's own account of a beetle (the common rose-chafer, Cetonia aurata) flying into his consulting room directly following on from his patient telling him a dream featuring a golden scarab.[97] The concept only makes sense psychologically and cannot be reduced to a verified or scientific fact. For Jung it constitutes a working hypothesis which has subsequently given rise to many ambiguities.

I chose this term because the simultaneous occurrence of two meaningfully but not causally connected events seemed to me an essential criterion. I am therefore using the general concept of synchronicity in the special sense of a coincidence in time of two or more causally unrelated events which have the same or a similar meaning, in contrast to synchronism, which simply means the simultaneous occurrence of two events. Synchronicity therefore means the simultaneous occurrence of a certain psychic state with one or more external events which appear as meaningful parallels to the momentary subjective state -and, in certain cases, vice versa.[98][99]

According to Jung, an archetype which has been constellated in the psyche can, under certain circumstances, transgress the boundary between substance and psyche.

Jung had studied such phenomena with the physicist and Nobel Prize winner, Wolfgang Pauli, who did not always agree with Jung, and with whom he carried on an extensive correspondence, enriched by the contributions of both specialists in their own fields.[100] Pauli had given a series of lectures to the C. G. Jung Institute, Zürich whose member and patron he had been since 1947.[34] It gave rise to a joint essay: Synchronicity, an a-causal principle (1952)[101][102] The two men saw in the idea of synchronicity a potential way of explaining a particular relationship between "incontrovertible facts", whose occurrence is tied to unconscious and archetypal manifestations,

The psyche and matter are ordered according to principles which are common, neutral, and incontrovertible.[103]

Borrowing the notion from Arthur Schopenhauer, Jung calls it Unus mundus, a state where neither matter nor the psyche are distinguishable.[34] whereas for Pauli it was a limiting concept, in two senses, in that it is at once scientific and symbolic. According to him, the phenomenon is dependent on the observer.[104] Nevertheless, both men were in accord that there existed the possibility of a conjunction between physics and psychology. Jung wrote in a letter to Pauli:

These researches (Jung's research into alchemy), have shown me that modern physics can symbolically represent psychological processes down to the minutest detail.[105]

Marie-Louise von Franz also had a lengthy exchange of letters with Wolfgang Pauli. On Pauli's death in 1958, his widow, Franca, deliberately destroyed all the letters von Franz had sent to her husband, and which he had kept locked inside his writing desk. However, the letters from Pauli to von Franz were all saved and were later made available to researchers and published.[106]

Synchronicity is among the most developed ideas by Jung's followers, notably by Michel Cazenave , James Hillman, Roderick Main,[107] Carl Alfred Meier and by the British developmental clinician, George Bright.[108] It has been explored also in a range of spiritual currents who have sought in it a scientific rigour.[109]

Although Synchronicity as conceived by Jung within the bounds of the science available in his day, has been categorised as pseudoscience, recent developments in complex adaptive systems argue for a revision of such a view.[73] Critics cite that Jung's experiments that sought to provide statistical proof for this theory did not yield satisfactory result.[110] His experiment was also faulted for not using a true random sampling method as well as for the use of dubious statistics and astrological material.[110]

Post-Jungian approaches

Andrew Samuels (1985) has distinguished three distinct traditions or approaches of "post-Jungian" psychology – classical, developmental and archetypal. Today there are more developments.

Classical

The classical approach tries to remain faithful to Jung's proposed model, his teachings and the substance of his 20 volume Collected Works, together with recently published works, such as the Liber Novus,[111] and the Black Books.[112] Prominent advocates of this approach, according to Samuels (1985), include Emma Jung, Jung's wife, an analyst in her own right, Marie-Louise von Franz, Joseph L. Henderson, Aniela Jaffé, Erich Neumann, Gerhard Adler and Jolande Jacobi. Jung credited Neumann, author of "Origins of Conscious" and "Origins of the Child", as his principal student to advance his (Jung's) theory into a mythology-based approach.[113] He is associated with developing the symbolism and archetypal significance of several myths: the Child, Creation, the Hero, the Great Mother and Transcendence.[10]

Archetypal

One archetypal approach, sometimes called "the imaginal school" by James Hillman, was written about by him in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Its adherents, according to Samuels (1985), include Gerhard Adler, Irene Claremont de Castillejo, Adolf Guggenbühl-Craig, Murray Stein, Rafael López-Pedraza and Wolfgang Giegerich. Thomas Moore also was influenced by some of Hillman's work. Developed independently, other psychoanalysts have created strong approaches to archetypal psychology. Mythopoeticists and psychoanalysts such as Clarissa Pinkola Estés who believes that ethnic and aboriginal people are the originators of archetypal psychology and have long carried the maps for the journey of the soul in their songs, tales, dream-telling, art and rituals; Marion Woodman who proposes a feminist viewpoint regarding archetypal psychology. Some of the mythopoetic/archetypal psychology creators either imagine the Self not to be the main archetype of the collective unconscious as Jung thought, but rather assign each archetype equal value. Others, who are modern progenitors of archetypal psychology (such as Estés), think of the Self as the thing that contains and yet is suffused by all other archetypes, each giving life to the other.

Robert L. Moore has explored the archetypal level of the human psyche in a series of five books co-authored with Douglas Gillette, which have played an important role in the men's movement in the United States. Moore studies computerese so he uses a computer's hard wiring (its fixed physical components) as a metaphor for the archetypal level of the human psyche. Personal experiences influence the access to the archetypal level of the human psyche, but personalized ego consciousness can be likened to computer software.

Developmental

A major expansion of Jungian theory is credited to Michael Fordham and his wife, Frieda Fordham. It can be considered a bridge between traditional Jungian analysis and Melanie Klein's object relations theory. Judith Hubback and William Goodheart MD are also included in this group.[114] Andrew Samuels (1985) considers J.W.T. Redfearn, Richard Carvalho and himself as representatives of the developmental approach. Samuels notes how this approach differs from the classical by giving less emphasis to the Self and more emphasis to the development of personality; he also notes how, in terms of practice in therapy, it gives more attention to transference and counter-transference than either the classical or the archetypal approaches.

Sandplay therapy

Sandplay is a non-directive, creative form of therapy using the imagination, originally used with children and adolescents, later also with adults. Jung had stressed the importance of finding the image behind the emotion. The use of sand in a suitable tray with figurines and other small toys, farm animals, trees, fences and cars enables a narrative to develop through a series of scenarios. This is said to express an ongoing dialogue between the conscious and the unconscious aspects of the psyche, which in turn activates a healing process whereby the patient and therapist can together view the evolving sense of self.[115]

Jungian Sandplay started as a therapeutic method in the 1950s. Although its origin has been credited to a Swiss Jungian analyst, Dora Kalff it was in fact, her mentor and trainer, Dr. Margaret Lowenfeld, a British paediatrician, who had developed the Lowenfeld World Technique inspired by the writer H. G. Wells in her work with children,[116] using a sand tray and figurines in the 1930s.[117] Jung had witnessed a demonstration of the technique while on a visit to the UK in 1937. Kalff saw in it potential as a further application of analytical psychology. Encouraged by Jung, Kalff developed the new application over a number of years and called it Sandplay.[118] From 1962 she began to train Jungian Analysts in the method including in the United States, Europe and Japan. Both Kalff and Jung believed an image can offer greater therapeutic engagement and insight than words alone. Through the sensory experience of working with sand and objects, and their symbolic resonance new areas of awareness can be brought into consciousness, as in dreams, which through their frames and storyline can bring material into consciousness as part of an integrating and healing process. The historian of psychology, Sonu Shamdasani has commented:

Historical reflection suggests the spirit of Jung's practice of the image, his engagement with his own figures, is indeed more alive in Sandplay than in other Jungian conclaves.[119]

One of Dora Kalff's trainees was the American concert pianist, Joel Ryce-Menuhin, whose music career was ended by illness and who retrained as a Jungian analyst and exponent of sandplay.[120]

Process-oriented psychology

Process-oriented psychology (also called Process work) is associated with the Zurich-trained Jungian analyst Arnold Mindell. Process work developed in the late 1970s and early 1980s and was originally identified as a "daughter of Jungian psychology".[121] Process work stresses awareness of the "unconscious" as an ongoing flow of experience. This approach expands Jung's work beyond verbal individual therapy to include body experience, altered and comatose states as well as multicultural group work.

The Analytic attitude

Formally Jungian analysis differs little from psychoanalysis. However, variants of each school have developed overlaps and specific divergences through the century, or more, of their existence. They share a "frame" consisting of regular spatio-temporal meetings, one or more times a week, focusing on patient material, using dialogue which may consist of elaboration, amplification and abreaction and which may last on average three years (sometimes more briefly or far longer). The spatial arrangement between analyst and analysand may differ: seated face to face or the patient may use the couch with the analyst seated behind.[122]

In some approaches alternative elements of expression can take place, such as active imagination, sandplay,[123] drawing or painting, even music. The session may at times become semi-directed (in contrast to psychoanalytic treatment which is essentially a non-directive encounter).[122]: 738 The patient is at the heart of the therapy, as Marie Louise von Franz has it in her work, "Psychotherapy: the practitioner's experience", where she recounts Jung's thinking on that point.[124] The transference is sought out (contrary to psychoanalytic treatment which distinguishes positive and negative transferences) and, the interpretation of dreams is one of the central pillars of Jungian psychotherapy. In all other respects, the rules correspond to those of classical psychoanalysis: the analyst examines free associations and tries to be objective and ethical, meaning respectful of the patient's pace and rhythm of unfolding progress. In fact, the task of Jungian analysis is not merely to explore the patient's past, but to connect conscious awareness with the unconscious such that a better adaptation to their emotional and social life may ensue.

Neurosis is not a symptom of the re-emergence of a repressed past, but is regarded as the functional, sometimes somatic, incapacity to face certain aspects of lived reality. In Jungian analysis the unconscious is the motivator whose task it is to bring into awareness the patient's shadow, in alliance with the analyst, the more so since unconscious processes enacted in the transference provoke a dependent relationship by the analysand on the analyst, leading to a falling away of the usual defences and references. This requires that the analyst guarantee the safety of the transference.[125] The responsibilities and accountability of individual analysts and their membership organisations, matters of clinical confidentiality and codes of ethics and professional relations with the public sphere are explored in a volume edited by Solomon and Twyman, with contributions from Jungian analysts and psychoanalysts.[126] Solomon has characterised the nature of the patient – analyst relationship as one where the analytic attitude is an ethical attitude since:

The ethical attitude presupposes special responsibilities that we choose to adopt in relation to another. Thus, a parallel situation pertains between caregiver and child and between analyst and patient: they are not equal partners, but nevertheless are in a situation of mutuality, shared subjectivity, and reciprocal influence.[127]

Jungian social, literary and art criticism

Analytical psychology has inspired a number of contemporary academic researchers to revisit some of Jung's own preoccupations with the role of women in society, with philosophy and with literary and art criticism.[128][129] Leading figures to explore these fields include the British-American, Susan Rowland, who produced the first feminist revision of Jung and the fundamental contributions made to his work by the creative women who surrounded him.[130] She has continued to mine his work by evaluating his influence on modern literary criticism and as a writer.[131] Leslie Gardner has devoted a series of volumes to analytical psychology in 21st century life, one of which concentrates on the "Feminine Self".[132] Paul Bishop, a British German scholar, has placed analytical psychology in the context of precursors such as, Goethe, Schiller and Nietzsche.[133][134]

The Franco-Swiss art historian and analytical psychologist, Christian Gaillard, has examined Jung's place as an artist and art critic in his series of Fay lectures at the Texas A&M University.[135] These scholars draw from Jung's works that apply analytical psychology to literature such as the lecture "On the Relation of Analytical Psychology to Poetry".[136] In this presentation, which was delivered in 1922, Jung stated that the psychologist cannot replace the art critic.[137] He rejected the Freudian art criticism for reducing complex works of art to Oedipal fantasies of their creators, stressing the danger of simplifying literature to causes found outside of the actual work.[137]

Criticism

Since its inception, analytical psychology has been the object of criticism, emanating from the psychoanalytic sphere. Freud himself characterised Jung as a "mystic and a snob".[138] In his introduction to the 2011 edition of Jung's "Lectures on the Theory of Psychoanalysis", given in New York City in 1912, Sonu Shamdasani contends that Freud orchestrated a round of critical reviews of Jung's writings from Karl Abraham, Jung's former colleague at the Burghölzli hospital, and from the early Welsh Freudian, Ernest Jones.[139][140][141] Such criticisms multiplied during the 20th century, focusing primarily on the "mysticism" in Jung's writings. Other psychoanalysts, including Jungian analysts, objected to the cult of personality around the Swiss psychiatrist.[142] It reached a crescendo with Jung's perceived collusion with Nazism in the build-up and during World War II and is still a recurrent theme. Thomas Kirsch writes: "Successive generations of Jungian analysts and analysands have wrestled with the question of Jung's complex relations to Germany."[109] Other considered evaluations come from Andrew Samuels and from Robert Withers.[143][144]

The French philosopher, Yvon Brès , considers that the concept of the collective unconscious, "shows also how easily one can slip from the psychological unconscious into perspectives from a universe of thought, quite alien from traditional philosophy and science, where this idea arose." ("Le concept jungien d'inconscient collectif "témoigne également de la facilité avec laquelle on peut glisser du concept d'inconscient psychologique vers des perspectives relevant d'un univers de pensée étranger à la tradition philosophique et scientifique dans laquelle ce concept est né'").[145]

In his Le Livre Rouge de la psychanalyse ("Red Book of psychoanalysis"), the French psychoanalyst, Alain Amselek , criticizes Jung's tendency to be fascinated by the image and to reduce the human to an archetype. He contends that Jung dwells in a world of ideas and abstractions, in a world of books and old secrets lost in ancient books of spells (fr: grimoires). While claiming to be an empiricist, Amselek finds Jung to be an idealist, a pure thinker who has unquestionably demonstrated his intellectual talent for speculation and the invention of ideas. While he considers his epistemology to be in advance of that of Freud, Jung remains stuck in his intellectualism and in his narrow provincial outlook. In fact, his hypotheses are determined by the concept of his postulated pre-existing world and he has constantly sought to find confirmations of it in the old traditions of Western Medieval Europe.[146]

More problematic has been, at times, the ad hominem criticism of academics outside the field of analytical psychology. One, a Catholic historian of psychiatry, Richard Noll, wrote three volumes but was able to publish only the first two in 1994 and 1997.[147][148] Nolls argued that analytical psychology is based on a neo-pagan Hellenistic cult.[128] These attacks on Jung and his work prompted the French psychoanalyst, Élisabeth Roudinesco, to state in a review: "Even if Noll's theses are based on a solid familiarity with the Jungian corpus [...], they deserve to be re-examined, such is the detestation of the author for the object of his study that it diminishes the credibility of the arguments." ("Même si les thèses de Noll sont étayées par une solide connaissance du corpus jungien [...], elles méritent être réexaminées, tant la détestation de l'auteur vis-à-vis de son objet d'étude diminue la crédibilité de l'argumentation.")[149] Another, a French ethnographer and anthropologist, Jean-Loïc Le Quellec , criticized Jung over his alleged misuse of the term archetype and his "suspect motives" in dealings with some of his colleagues.[150]

See also

References

- Jung, C. G. (1912). Neue Bahnen in der Psychologie (in German). Zürich.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) (New Pathways in Psychology) - Samuels, Andrew; Shorter, B.; Plaut, F. (1986). A Critical Dictionary of Jungian Analysis. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 978-0-415-05910-7.

- "Analytic Psychology". Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Complete Digital Edition. Princeton University Press. March 2014. ISBN 9781400851065. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- Fordham, Michael (1978). Jungian Psychotherapy: A Study in Analytical Psychology. London: Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–8. ISBN 0-471-99618-1.

- Anthony Stevens (1990). Archetype: A Natural History of the Self. Hove: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415052207.

- Jung, Carl Gustav (1 August 1971). "Psychological Types". Collected Works of C. G. Jung, Volume 6. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09770-1.

- McCrae, R.; Costa, P. (1989), Reinterpreting the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator from the perspective of the five-factor model of personality.

- Ann Addison (2009). "Jung, vitalism and 'the psychoid': an historical reconstruction". Journal of Analytical Psychology. 54 (1): 123–142. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5922.2008.01762.x. PMID 19161521.

- Samuels, Andrew (1985). Jung and the Post-Jungians. London and Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul plc. pp. 11–21. ISBN 0-7100-9958-4.

- Remo, F. Roth (2012). Return of the World Soul, Wolfgang Pauli, C. G. Jung and the Challenge of Psychophysical Reality [unus mundus], Part 2: A Psychophysical Theory. Pari Publishing. ISBN 978-88-95604-16-9.

- Samuels, Andrew, ed. (1985). The Father: Contemporary Jungian Perspectives. London: Free Association Books. ISBN 978-0-946960-28-6.

- Kutek, Ann (1999). "The terminal as a substitute for the interminable?". Psychodynamic Counselling. 5: 7–24. doi:10.1080/13533339908404188.

- Huskinson, Lucy (2018). Architecture and the Mimetic Self: A Psychoanalytic Study of How Buildings Make and Break Our Lives. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-69303-5.

- Redfearn, J.W.T. (1992). The Exploding Self: The Creative and Destructive Nucleus of the Personality. Chiron.

- Wisdom of the Dream (Carl Jung) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ci9nfJbvBjY a Stephen Segaller production.

- Hubback, Judith (2013). People Who Do Things to Each Other. Chiron Publishers. ISBN 978-0-933029279.

- Schaverien, Joy (2015). Boarding School Syndrome. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415690034.

- Mathers, Dale, ed. (2021). Depth Psychology and Climate Change: The Green Book. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-367-23721-9.

- Jung. CW 1. pp. 3–88

- Bair, Deirdre (2004). Jung, A Biography. London: Little Brown. ISBN 0-316-85434-4.

- Binswanger, L. (1919). "XII". In Jung, Carl (ed.). Studies in Word-Association. New York, NY: Moffat, Yard & company. pp. 446 et seq. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Note: Jung was so impressed with EDA monitoring, he allegedly cried, "Aha, a looking glass into the unconscious!"

- Brown, Barbara (9 November 1977). "Skin Talks – And It May Not Be Saying What You Want To". Pocatello, Idaho: Field Enterprises, Inc. Idaho State Journal. p. 32. Retrieved 8 April 2015.

- Mitchell, Gregory. "Carl Jung & Jungian Analytical Psychology". Mind Development Courses. Retrieved 9 April 2015.

- Daniels, Victor. "Notes on Carl Gustav Jung". Sonoma State University. Retrieved 4 April 2015.

By 1906 [Jung] was using GSR and breath measurement to note changes in respiration and skin resistance to emotionally charged worlds. He found that indicators cluster around stimulus words which indicate the nature of the subject's complexes.

- The Biofeedback Monitor Archived 15 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Wehr, Gerhard (1987). Jung – A Biography. Translated by Weeks, David. M. Boston: Shambala. pp. 501–505. ISBN 0-87773-455-0.

- Roazen, Paul. (1976) Erik Erikson, pp. 8-9. The Harvard Fellowship was intended for Freud who was too ill to travel, so to save emoluments going elsewhere, it was offered to Jung, who accepted.

- Martin-Vallas François (2013). "Quelques remarques à propos de la théorie des archétypes et de son épistémologie". Revue de Psychologie Analytique (in French). 1 (1): 99–134. doi:10.3917/rpa.001.0099..

- Jung on film.

- "Jungian Psychoanalysis". new. Retrieved 21 November 2021.

- Vaughan, Alan G. (9 August 2013). "Jung, Analytical Psychology, and Transpersonal Psychology". The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Transpersonal Psychology: 141–154. doi:10.1002/9781118591277.ch7. ISBN 9781119967552.

- Bair, Deirdre (2004). Jung – A Biography. Little, Brown. p. 553. ISBN 0-316-85434-4.

- Baudouin, Charles. L'Œuvre de Carl Jung et la psychologie complexe, Paris, Petite bibliothèque Payot, coll. " numéro 133 ", 2002 (ISBN 978-2-228-89570-5) (in French)

- Karl Abraham (1969). Critique de l'essai d'une présentation de la théorie psychanalytique de C. G. Jung. pp. 207–224

- Jung, Carl (1963). Memories, Dreams, Reflections. Pantheon Books. p. 206.

- Carlson, Heth (2010). Psychology: The Science of Behavior. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. p. 434. ISBN 978-0-205-64524-4.

- Jung. CW. 7. para. 266.

- Jung. CW. 12. para. 44

- Jung. CW 11, para. 391.

- Hoerni, Ulrich; Fischer, Thomas; Kaufmann, Bettina, eds. (2019). The Art of C.G. Jung. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-393-25487-7.

- Shamdasani, Sonu (2003). Jung and the making of modern psychology: the dream of a science. Cambridge University Press. p. 59..

- Jung, C. G. (1994). Correspondence (in French). Vol. 3, 1950–1954. Albin Michel. p. Letter of 14 May 1950 to Joseph Goldbrunner.

- Aurigemma, Luigi (2009). L'Éveil de la conscience (in French). Paris: L'Herne, coll. " Carnets ". p. 54. ISBN 978-2-85197-446-4.

- C. G. Jung (1950). Psychological Types. Georg. pp. 85–86.

- M. L. Hoffman of The New York Times in Geneva, as part of research for an article about Freud, Jung answered point by point questions concerning his attitude to the psychoanalysis of the Viennese doctor, on 24 July 1953 in "Replies to questions about Freud". adequations.org. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- Jung, C. G. The Red Book: Liber Novus. Philemon Foundation and W. W. Norton & Co., 2009. ISBN 978-0-393-06567-1, (manuscript produced circa 1915–1932).

- Jung, C. G. The Black Books. Philemon Foundation and W. W. Norton & Co., 2020. ISBN 978-0-3930-8864-9, (private journals produced circa 1913–1932, on which the Red Book is based).

- Stevens, Anthony (1998). An Intelligent Person's Guide to Psychotherapy. London: Gerald Duckworth & Co. p. 67. ISBN 0-7156-2820-8.

- Jung. CW 16. paras. 364-65.

- Fordham, Michael (1978). Jungian Psychotherapy, A Study in Analytical Psychology. London: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. ISBN 0-471-99618-1.

- Jung, C. G. Psychiatric Studies. The Collected Works of C. G. Jung Vol. 1. 1953, edited by Michael Fordham. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul / Princeton, NJ: Bollingen.

- Jung, C. G. Psychology of the Unconscious: a study of the transformations and symbolisms of the libido, a contribution to the history of the evolution of thought, translated by B. M. Hinkle, 1916. London: Kegan Paul Trench Trubner. (Revised in 1952 as Symbols of Transformation.)

- Agnel, Aimé; Cazenave, Michel; Dorly, Claire; Krakowiak, Suzanne; Thibaudier Vivianne; Vandenbroucke, Bernadette, eds. (2005). Le Vocabulaire de Jung. coll. Vocabulaire de... (in French). Paris: Ellipses. pp. 80 ff. ISBN 978-2-7298-2599-7.

- Baudouin, Charles (2002). L'Œuvre de Carl Jung et la psychologie complexe. coll. " numéro 133 " (in French). Paris: Petite bibliothèque Payot. p. 116. ISBN 978-2-228-89570-5.

- Jung, C. G. (1964). Man and his Symbols (in French). Robert Laffont. p. 52..

- Jung, C. G. (1988). Essai d'exploration de l'inconscient (in French). Gallimard. p. 43. ISBN 978-2-07-032476-7.

- Naiman, Rubin (2020). "We Live in a Wake-centric World Losing Touch with our Dreams". Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- Nataf, André (1985). Jung. Le Monde de (in French). Paris: Édition MA. p. 209. ISBN 978-2-86676-192-9.

- de Mijolla, Alain, ed. (2005). International Dictionary of Psychoanalysis. MacMillan Reference Books. ISBN 0-02-865924-4.

- Jackson, Kathy Merlock (2005). Rituals and Patterns in Children's Lives. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press. p. 225. ISBN 0-299-20830-3.

- Ivancevic, Vladimir G.; Ivancevic, Tijana T. (2007). Computational Mind: A Complex Dynamics Perspective. Berlin: Springer. p. 108. ISBN 9783540714651.

- Jung, C. G. (21 September 1988). Nietzsche's Zarathustra. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691099538.

- Maciocia, Giovanni (2009). The Psyche in Chinese Medicine: Treatment of Emotional and Mental Disharmonies with Acupuncture and Chinese Herbs. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-7020-2988-2.

- Stevens, Anthony Archetype Revisited: an Updated Natural History of the Self. Toronto, ON.: Inner City Books, 2003. p. 74.

- Smythe, William E; Baydala, Angelina (2012). "The hermeneutic background of C. G. Jung". Journal of Analytical Psychology. 57 (1): 57–75. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5922.2011.01951.x. PMID 22288541.

- "Wikischool". Wikischool. Archived from the original on 4 September 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2020.

- Colman, Warren (2018). "Are Archetypes Essential?". Journal of Analytical Psychology. 63 (3): 336–346. doi:10.1111/1468-5922.12414. PMID 29750343.

- Young-Eisendrath & Dawson, Cambridge Companion to Jung (2008), "Chronology" (pp. xxiii–xxxvii). According to the 1953 Collected Works editors, the 1916 essay was translated by M. Marsen from German into French and published as "La Structure de l'inconscient" in Archives de Psychologie XVI (1916); they state that the original German manuscript no longer exists.

- Jung, Collected Works vol. 7 (1953), "The Structure of the Unconscious" (1916), ¶437–507 (pp. 263–292).

- Jung, Collected Works vol. 8 (1960), "The Significance of Constitution and Heredity in Psychology" (1929), ¶229–230 (p. 112).

- Cambray, Joseph. "Synchronicity as emergence". In Cambray, Joseph; Carter, Linda (eds.). Analytical Psychology:Contemporary Perspectives in Jungian Analysis. Brunner-Routledge. p. 232.

- Roudinesco, p. 731

- Baudouin, Charles (2002). L'Œuvre de Carl Jung et la psychologie complexe. coll. no 133 (in French). Paris: Petite bibliothèque Payot. ISBN 978-2-228-89570-5.

- Aurigemma, p. 43.

- Jung, C. G. (1977). The Relations between the ego and the Unconscious. Collected Works. Vol. 7. Routledge & Kegan Paul. p. 172.

- Jung, C. G.; Keller, Adolf (2020). On Theology and Psychology: The Correspondence of C. G. Jung and Adolf Keller. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-691-19877-4.

- Jung, Carl Gustav (1999). Two Essays on Analytical Psychology. London: Routledge. p. 173. ISBN 0-415-08028-2.

- Wenzel, Amy (2017). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Abnormal and Clinical Psychology. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-5063-5322-7.

- Harris, Judith (2001). Jung and Yoga: The Psyche-body Connection. Toronto, ON: Inner City Books. p. 23. ISBN 0-919123-95-3.

- Aurigemma, p. 35

- Roudinesco, p. 732

- Brooke, Roger (2015). Jung and Phenomenology, Classic Edition. New York: Routledge. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-138-78727-8.

- Anthony Stevens, On Jung (London 1990) p. 43

- Jung, C. G. 1993. The Practice of Psychotherapy. London.

- Jung, C.G. (1958–1967). Psyche and Symbol. (R. F. C. Hull, Trans.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press (published 1991).

- Roudinesco. p. 727

- Gordon, Susan (2013). Neurophenomenology and Its Applications to Psychology. New York: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 140. ISBN 978-1-4614-7238-4.

- Moacanin, Radmila (2019). Jung and Islam: Two Pilgrims Leading to the Soul…. Pittsburgh, PA: Dorrance Publishing. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4809-9169-9.

- Hockley, Luke; Fadina, Nadi (2015). The Happiness Illusion: How the media sold us a fairytale. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-57982-3.

- Jung, C. G. CW, 9, pp. 122 ff.

- Brinich, Paul; Shelley, Christopher (2002). The Self and Personality Structure. Philadelphia, PA: McGraw-Hill Education (UK). p. 72. ISBN 0-335-20564-X.

- Jung, C.G., "Psychological Types" (The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol.6).

- Jung, C. G. (2012). Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle. (From Vol. 8. of the Collected Works of C. G. Jung). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. xiii. ISBN 978-1-4008-3916-2.

- Cambray, Joseph; Carter, Linda, eds. (2004). "9: Synchronicity as emergence". Analytical Psychology: Contemporary Perspectives in Jungian Analysis (PDF). Hove-New York: Brunner-Routledge. pp. 223–248. ISBN 1-58391-999-6.

- Jung, C.G. CW, 8. para. 845. "A young woman I was treating had, at a critical moment, a dream in which she was given a golden scarab. While she was telling me this dream I sat with my back to the closed window. Suddenly I heard a noise behind me, like a gentle tapping. I turned round and saw a flying insect knocking against the window-pane from outside. I opened the window and caught the creature in the air as it flew in. It was the nearest analogy to a golden scarab that one finds in our latitudes, a scarabaeid beetle, the common rose chafer (Cetonia aurata), which contrary to its usual habits had evidently felt an urge to get into a dark room at this particular moment. I must admit that nothing like it ever happened to me before or since, and that the dream of the patient has remained unique in my experience."

- Jung, C.G. CW, 8. paras. 849–850.

- Pallud, Pierre (1981). "L'idée de synchronicité dans l'œuvre de Jung". Cahiers jungiens de psychanalyse (in French) (28): 2..

- Jung, C. G.; Pauli, Wolfgang; Meier, C. A.; Zabriskie, Beverley; Roscoe, David (1 July 2014). Atom and Archetype: The Pauli/Jung Letters, 1932–1958. Princeton University Press. p. xxxiii. ISBN 978-0-691-16147-1.

- Jung, Carl Gustav, and Wolfgang Ernst Pauli. [1952] 1955. The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche, translated from German Naturerklärung und Psyche.

- A summary of their research is available in German. Pauli, W. (December 1954). "Naturwissenschaftliche und erkenntnistheoretische aspekte der ideen vom unbewussten". Dialectica (in German). 8 (4): 283–301. doi:10.1111/j.1746-8361.1954.tb01265.x.

- The Correspondence of Pauli and Jung ', Albin Michel, 2007, p.162.

- Liard, Véronique (2007). Carl Gustav Jung, Kulturphilosoph (in French). Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 148. ISBN 9782840504146.

- Pauli, Wolfgang; Jung, Carl (2007). Correspondance Pauli-Jung, (Pauli-Jung correspondence) (in French). Albin Michel. p. 248.

- Gieser, Suzanne (2005). The innermost kernel : depth psychology and quantum physics : Wolfgang Pauli's dialogue with C.G. Jung. Berlin [u.a.]: Springer. ISBN 9783540208563.

- Main, Roderick (1997). Jung on Synchronicity and the Paranormal. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691058375.

- Bright, George (2006). "Synchronicity as A Basis of Analytic Attitude". Journal of Analytical Psychology. 42 (4): 613–635. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1997.00613.x.

- Kirsch, Thomas (2000). The Jungians: a comparative and historical perspective. Routledge. pp. 244–245.

- Aziz, Robert (1990). C. G. Jung's Psychology of Religion and Synchronicity. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 224. ISBN 0-7914-0166-9.

- The Red Book: Liber Novus. tr. M. Kyburz, J. Peck and S. Shamdasani. New York: W. W. Norton, 2009. ISBN 978-0-393-06567-1.

- Jung, C.G. (October 2020). Shamdasani, Sonu (ed.). The Black Books of C.G. Jung (1913–1932). Translated by Liebscher, Martin; Peck, John; Shamdasani, Sonu. Philemon Foundation & W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-3930-8864-9.

- Jung, C. G.; Neumann, Erich (2015). Liebscher, Martin (ed.). Analytical Psychology in Exile: The Correspondence of C. G. Jung and Erich Neumann (Philemon Foundation Series). Translated by Heather McCartney. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691166179.

- "Obituary: William Godheart (1934–2020)". www.legacy.com.

- "Jungian Sandplay". British and Irish Sandplay Society. Archived from the original on 8 May 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- H. G. Wells' Floor Games has been regarded as a precursor not only of learning through play but also of nonverbal child psychotherapy. See Barbara A. Turner's 2004 edition, published by Temenos Press of Coverdale, CA.

- Sandplay History – Techniques developed from Lowenfeld's World Technique Archived 12 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved, 28 June 2009

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Sandplay - Dora Kalff". YouTube.

- Shamdasani, S. (2015). "Jung's Practice of the Image". Journal of Sandplay Therapy. 24 (1).

- Ryce-Menuhin, J. (1992). Jungian sandplay: The wonderful therapy. London & New York: Routledge Press. ISBN 0415047757.

- Julie Diamond (2004). A Path Made by Walking. Lao Tse Press. p. 6.

In the mid-1980s, Arnold Mindell presented a lecture called 'Jungian Psychology has a Daughter' to the Jungian community in Zurich.

- Roudinesco, Élisabeth; Plon, Michel (2011). "Entrée " Jung "". Dictionnaire de la psychanalyse (in French). Paris: Fayard. ISBN 978-2-253-08854-7.

- Kirsch, Thomas B. (2012). The Jungians: A Comparative and Historical Perspective. Routledge. pp. 233–236. ISBN 9781134725519.

- von Franz, M-L. 1990 Psychotherapie. Erfahrungen aus der Praxis. (Gesammelte Aufsätze Bd. 3). Daimon, Einsiedeln/Zürich. ISBN 3-85630-036-8. (in German)

- Extracted from "Code de déontologie de la SFPA (Code of Ethics of the French Society of Analytical Psychology)" (in French). cgjungfrance.com. Archived from the original on 1 March 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2011..

- Woodhead, J. (2004). "SOLOMON, HESTER MCFARLAND & TWYMAN, MARY (Eds.). The Ethical Attitude in Analytic Practice. London: Free Association Books, 2003. Pp. 178. Pbk. £18.95". Journal of Analytical Psychology. 49 (4): 587–589.

- Solomon, Hester McFarland (2002). "Origins of the ethical attitude". Journal of Analytical Psychology. 46 (3): 443–454. doi:10.1111/1465-5922.00256. PMID 11471333.

- Bishop, Paul (2008). Analytical Psychology and German Classical Aesthetics: Goethe, Schiller, and Jung, Volume 1: The Development of the Personality. Oxon: Routledge. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-1-58391-808-1.

- Samuels, Andrew (2015). Passions, Persons, Psychotherapy, Politics: The selected works of Andrew Samuels. East Sussex: Routledge. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-1-317-64385-2.

- Rowland, Susan (2002). Jung: A feminist revision. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-7456-2517-1.

- Rowland, Susan (2005). Jung as a Writer. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-5839-1902-6.

- Gardner, Leslie; Miller, Catriona, eds. (2020). Exploring Depth Psychology and the Female Self: Feminist Themes from Somewhere. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-3673-3065-1.

- Bishop, Paul (2007). Analytical Psychology and German Classical Aesthetics: Goethe, Schiller and Jung. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-58391-809-8.

- Bishop, P (2016). On the Blissful Islands: With Nietzsche and Jung: in the Shadow of the Superman. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-1387-9161-9.

- Gaillard, Christian (2019). Rosen, David (ed.). The Soul of Art: Analysis and Creation. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-6234-9526-8.

- Young-Eisendrath, Polly; Dawson, Terence (2008). The Cambridge Companion to Jung, Second Edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-521-86599-9.

- Rowland, Susan (2018). Jungian Literary Criticism: The Essential Guide. Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-20229-5.

- Vandermeersch, Patrick (1991). Unresolved Questions in the Freud/Jung Debate. On Psychosis, Sexual Identity and Religion. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- Jung, C.G (2011). Shamdasani, Sonu (ed.). Jung Contra Freud: The 1912 New York Lectures on the Theory of Psychoanalysis. Translated by Hull, R. F. C. Princeton University Press. p. XX. ISBN 978-0-6911-5251-6.

- Abraham, Karl (1955). Abraham, Hilda (ed.). Clinical Papers and Essays on Psychoanalysis. Translated by Abraham, Hilda; Ellison, D. R. London: Hogarth Press. pp. 101–15.

- Jones, Ernest (1911). "Zur Psychoanalyse der christlichen Religion". Internationale Zeitschrift für Ärztliche Psychoanalyse. 2: 83–86.

- Steven, Anthony (October 1997). "The Jung Cult: Origins of a Charismatic Movement/The Aryan Christ: The Secret Life of Carl Jung (book)". Journal of Analytical Psychology. 42 (4): 671 – via EBSCOhost.

- Samuels, A., (1985). Jung and the Post-Jungians. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-7100-9958-4

- Withers, Robert (2003). Controversies in Analytical Psychology. Hove: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-23305-7.

- Brès, Yvon (2002). L'Inconscient. Philo (in French). Paris: Ellipses. p. 123. ISBN 2-7298-0974-0.

- Amselek, Alain (2010). Le Livre Rouge de la psychanalyse (in French). Paris: Desclée de Brouwer. pp. 85–119.

- Noll, Richard. The Jung Cult: Origins of a Charismatic Movement. Princeton: Princeton University Press. 1994. ISBN 0-684-83423-5

- Noll, Richard. The Aryan Christ: The Secret Life of Carl Jung. New York: Random House. 1997. ISBN 0-679-44945-0