Attic Greek

Attic Greek is the Greek dialect of the ancient region of Attica, including the polis of Athens. Often called classical Greek, it was the prestige dialect of the Greek world for centuries and remains the standard form of the language that is taught to students of ancient Greek. As the basis of the Hellenistic Koine, it is the most similar of the ancient dialects to later Greek. Attic is traditionally classified as a member or sister dialect of the Ionic branch.

| Attic Greek | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ἀττική Ἑλληνική | ||||||

| Region | Attica, Aegean Islands | |||||

| Era | c. 500–300 BC; evolved into Koine | |||||

Indo-European

| ||||||

Early form | ||||||

| Greek alphabet Old Attic alphabet | ||||||

| Language codes | ||||||

| ISO 639-3 | – | |||||

grc-att | ||||||

| Glottolog | atti1240 | |||||

_en.svg.png.webp) Distribution of Greek dialects in Greece in the classical period.[1]

Distribution of Greek dialects in Magna Graecia (Southern Italy and Sicily) in the classical period.

| ||||||

Origin and range

Greek is the primary member of the Hellenic branch of the Indo-European language family. In ancient times, Greek had already come to exist in several dialects, one of which was Attic. The earliest attestations of Greek, dating from the 16th to 11th centuries BC, are written in Linear B, an archaic writing system used by the Mycenaean Greeks in writing their language; the distinction between Eastern and Western Greek is believed to have arisen by Mycenaean times or before. Mycenaean Greek represents an early form of Eastern Greek, the group to which Attic also belongs. Later Greek literature wrote about three main dialects: Aeolic, Doric, and Ionic; Attic was part of the Ionic dialect group. "Old Attic" is used in reference to the dialect of Thucydides (460–400 BC) and the dramatists of 5th-century Athens whereas "New Attic" is used for the language of later writers following conventionally the accession in 285 BC of Greek-speaking Ptolemy II to the throne of the Kingdom of Egypt. Ruling from Alexandria, Ptolemy launched the Alexandrian period, during which the city of Alexandria and its expatriate Greek-medium scholars flourished.[2]

The original range of the spoken Attic dialect included Attica and a number of the Aegean Islands; the closely related Ionic was also spoken along the western and northwestern coasts of Asia Minor in modern Turkey, in Chalcidice, Thrace, Euboea, and in some colonies of Magna Graecia. Eventually, the texts of literary Attic were widely studied far beyond their homeland: first in the classical civilizations of the Mediterranean, including in Ancient Rome and the larger Hellenistic world, and later in the Muslim world, Europe, and other parts of the world touched by those civilizations.

Literature

The earliest Greek literature, which is attributed to Homer and is dated to the eighth or seventh centuries BC, is written in "Old Ionic" rather than Attic. Athens and its dialect remained relatively obscure until the establishment of its democracy following the reforms of Solon in the sixth century BC; so began the classical period, one of great Athenian influence both in Greece and throughout the Mediterranean.

The first extensive works of literature in Attic are the plays of dramatists Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, and Aristophanes dating from the fifth century BC. The military exploits of the Athenians led to some universally read and admired history, as found in the works of Thucydides and Xenophon. Slightly less known because they are more technical and legal are the orations by Antiphon, Demosthenes, Lysias, Isocrates, and many others. The Attic Greek of philosophers Plato (427–347 BC) and his student Aristotle (384–322 BC) dates to the period of transition between Classical Attic and Koine.

Students who learn Ancient Greek usually begin with the Attic dialect and continue, depending upon their interests, to the later Koine of the New Testament and other early Christian writings, to the earlier Homeric Greek of Homer and Hesiod, or to the contemporaneous Ionic Greek of Herodotus and Hippocrates.

Alphabet

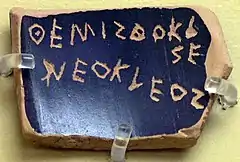

Attic Greek, like other dialects, was originally written in a local variant of the Greek alphabet. According to the classification of archaic Greek alphabets, which was introduced by Adolf Kirchhoff,[3] the old-Attic system belongs to the "eastern" or "blue" type, as it uses the letters Ψ and Χ with their classical values (/ps/ and /kʰ/), unlike "western" or "red" alphabets, which used Χ for /ks/ and expressed /kʰ/ with Ψ. In other respects, Old Attic shares many features with the neighbouring Euboean alphabet (which is "western" in Kirchhoff's classification).[4] Like the latter, it used an L-shaped variant of lambda (![]() ) and an S-shaped variant of sigma (

) and an S-shaped variant of sigma (![]() ). It lacked the consonant symbols xi (Ξ) for /ks/ and psi (Ψ) for /ps/, expressing these sound combinations with ΧΣ and ΦΣ, respectively. Moreover, like most other mainland Greek dialects, Attic did not yet use omega (Ω) and eta (Η) for the long vowels /ɔː/ and /ɛː/. Instead, it expressed the vowel phonemes /o, oː, ɔː/ with the letter Ο (which corresponds with classical Ο, ΟΥ, Ω) and /e, eː, ɛː/ with the letter Ε (which corresponds with Ε, ΕΙ, and Η in later classical orthography). Moreover, the letter Η was used as heta, with the consonantal value of /h/ rather than the vocalic value of /ɛː/.

). It lacked the consonant symbols xi (Ξ) for /ks/ and psi (Ψ) for /ps/, expressing these sound combinations with ΧΣ and ΦΣ, respectively. Moreover, like most other mainland Greek dialects, Attic did not yet use omega (Ω) and eta (Η) for the long vowels /ɔː/ and /ɛː/. Instead, it expressed the vowel phonemes /o, oː, ɔː/ with the letter Ο (which corresponds with classical Ο, ΟΥ, Ω) and /e, eː, ɛː/ with the letter Ε (which corresponds with Ε, ΕΙ, and Η in later classical orthography). Moreover, the letter Η was used as heta, with the consonantal value of /h/ rather than the vocalic value of /ɛː/.

In the fifth century, Athenian writing gradually switched from this local system to the more widely used Ionic alphabet, native to the eastern Aegean Islands and Asia Minor. By the late fifth century, the concurrent use of elements of the Ionic system with the traditional local alphabet had become common in private writing, and in 403 BC, it was decreed that public writing would switch to the new Ionic orthography, as part of the reform following the Thirty Tyrants. This new system, also called the "Eucleidian" alphabet, after the name of the archon Eucleides, who oversaw the decision,[5] was to become the Classical Greek alphabet throughout the Greek-speaking world. The classical works of Attic literature were subsequently handed down to posterity in the new Ionic spelling, and it is the classical orthography in which they are read today.

Phonology

Long a

Proto-Greek long ā → Attic long ē, but ā after e, i, r. ⁓ Ionic ē in all positions. ⁓ Doric and Aeolic ā in all positions.

- Proto-Greek and Doric mātēr → Attic mētēr "mother"

- Attic chōrā ⁓ Ionic chōrē "place", "country"

However, Proto-Greek ā → Attic ē after w (digamma), deleted by the Classical Period.[6]

- Proto-Greek korwā[7] → early Attic-Ionic *korwē → Attic korē (Ionic kourē)

Sonorant clusters

Compensatory lengthening of vowel before cluster of sonorant (r, l, n, m, w, sometimes y) and s, after deletion of s. ⁓ some Aeolic: compensatory lengthening of sonorant.[8]

- Proto-Indo-European *es-mi (athematic verb) → Attic-Ionic ēmi (= εἰμί) ⁓ Lesbian-Thessalian emmi "I am"

Upsilon

Proto-Greek and other dialects' /u/ (English food) became Attic /y/ (pronounced as German ü, French u) and represented by y in Latin transliteration of Greek names.

- Boeotian kourios ⁓ Attic kyrios "lord"

In the diphthongs eu and au, upsilon continued to be pronounced /u/.

Contraction

Attic contracts more than Ionic does. a + e → long ā.

- nika-e → nikā "conquer (thou)!"

e + e → ē (written ει: spurious diphthong)

- PIE *trey-es → Proto-Greek trees → Attic trēs = τρεῖς "three"

e + o → ō (written ου: spurious diphthong)

- early *genes-os → Ionic geneos → Attic genous "of a kind" (genitive singular: Latin generis, with r from rhotacism)

Vowel shortening

Attic ē (from ē-grade of ablaut or Proto-Greek ā) is sometimes shortened to e:

- when it is followed by a short vowel, with lengthening of the short vowel (quantitative metathesis): ēo → eō

- when it is followed by a long vowel: ēō → eō

- when it is followed by u and s: ēus → eus (Osthoff's law):

- basilēos → basileōs "of a king" (genitive singular)

- basilēōn → basileōn (genitive plural)

- basilēusi → basileusi (dative plural)

Hyphaeresis

Attic deletes one of two vowels in a row, called hyphaeresis (ὑφαίρεσις).

- Homeric boē-tho-os → Attic boēthos "running to a cry", "helper in battle"

Palatalization

PIE *ky or *chy → Proto-Greek ts (palatalization) → Attic and Euboean Ionic tt — Cycladean/Anatolian Ionic and Koine ss.

- Proto-Greek *glōkh-ya → Attic glōtta — East Ionic glōssa "tongue"

Sometimes, Proto-Greek *ty and *tw → Attic and Euboean Ionic tt — Cycladean/Anatolian Ionic and Koine ss.

- PIE *kwetwores → Attic tettares — East Ionic tesseres "four" (Latin quattuor)

Proto-Greek and Doric t before i or y → Attic-Ionic s (palatalization).

- Doric ti-the-nti → Attic tithēsi = τίθεισι "he places" (compensatory lengthening of e → ē = spurious diphthong ει)

Shortening of ss

Doric, Aeolian, early Attic-Ionic ss → Classical Attic s.

- PIE *medh-yos → Homeric μέσσος (messos) (palatalization) → Attic μέσος (mesos) "middle"

- Homeric ἐτέλεσσα → Attic ἐτέλεσα "I performed (a ceremony)"

- Proto-Greek *podsi → Homeric ποσσί → Attic ποσί "by foot"

- Proto-Greek *hopot-yos → dialectal ὁπόσσος → Attic ὁπόσος

Loss of w

Proto-Greek w (digamma) was lost in Attic before historical times.

- Proto-Greek korwā[10] Attic korē "girl"

Retention of h

Attic retained Proto-Greek h- (from debuccalization of Proto-Indo-European initial s- or y-), but some other dialects lost it (psilosis "stripping", "de-aspiration").

- Proto-Indo-European *si-sta-mes → Attic histamen — Cretan istamen "we stand"

Movable n

Attic-Ionic places an n (movable nu) at the end of some words that would ordinarily end in a vowel, if the next word starts with a vowel, to prevent hiatus (two vowels in a row). The movable nu can also be used to turn what would be a short syllable into a long syllable for use in meter.

- pāsin élegon "they spoke to everyone" vs. pāsi legousi

- pāsi(n) dative plural of "all"

- legousi(n) "they speak" (third person plural, present indicative active)

- elege(n) "he was speaking" (third person singular, imperfect indicative active)

- titheisi(n) "he places", "makes" (third person singular, present indicative active: athematic verb)

Rr instead of rs.

Attic and Euboean Ionic use rr in words, when Cycladean and Anatolian Ionic use rs:

- Attic χερρόνησος → East Ionic χερσόνησος "peninsula"

- Attic ἄρρεν → East Ionic ἄρσεν "male"

- Attic θάρρος → East Ionic θάρσος "courage".

Attic replaces the Ionic -σσ with -ττ

Attic and Euboean Ionic use tt, while Cycladean and Anatolian Ionic use ss:

- Attic γλῶττα → East Ionic γλῶσσα "tongue"

- Attic πράττειν → East Ionic πράσσειν "to do, to act"

- Attic θάλαττα → East Ionic θάλασσα "sea".[11]

Morphology

- Attic tends to replace the -ter "doer of" suffix with -tes: dikastes for dikaster "judge".

- The Attic adjectival ending -eios and corresponding noun ending, both having two syllables with the diphthong ei, stand in place of ēios, with three syllables, in other dialects: politeia, Cretan politēia, "constitution", both from politewia whose w is dropped.

Grammar

Attic Greek grammar follows Ancient Greek grammar to a large extent. References to Attic Grammar are usually in reference to peculiarities and exceptions from Ancient Greek Grammar. This section mentions only some of these Attic peculiarities.

Number

In addition to singular and plural numbers, Attic Greek had the dual number. This was used to refer to two of something and was present as an inflection in nouns, adjectives, pronouns and verbs (any categories inflected for number). Attic Greek was the last dialect to retain it from older forms of Greek, and the dual number had died out by the end of the 5th century BC. In addition to this, in Attic Greek, any plural neuter subjects will only ever take singular conjugation verbs.

Declension

With regard to declension, the stem is the part of the declined word to which case endings are suffixed. In the alpha or first declension feminines, the stem ends in long a, which is parallel to the Latin first declension. In Attic-Ionic the stem vowel has changed to ē in the singular, except (in Attic only) after e, i or r. For example, the respective nominative, genitive, dative and accusative singular forms are ἡ γνώμη τῆς γνώμης τῇ γνώμῃ τὴν γνώμην gnome, gnomes, gnome(i), gnomen, "opinion" but ἡ θεᾱ́ τῆς θεᾶς τῇ θεᾷ τὴν θεᾱ́ν thea, theas, thea(i), thean, "goddess".

The plural is the same in both cases, gnomai and theai, but other sound changes were more important in its formation. For example, original -as in the nominative plural was replaced by the diphthong -ai, which did not change from a to e. In the few a-stem masculines, the genitive singular follows the second declension: stratiotēs, stratiotou, stratiotēi, etc.

In the omicron or second declension, mainly masculines (but with some feminines), the stem ends in o or e, which is composed in turn of a root plus the thematic vowel, an o or e in Indo-European ablaut series parallel to similar formations of the verb. It is the equivalent of the Latin second declension. The alternation of Greek -os and Latin -us in the nominative singular is familiar to readers of Greek and Latin.

In Attic Greek, an original genitive singular ending *-osyo after losing the s (like in the other dialects) lengthens the stem o to the spurious diphthong -ou (see above under Phonology, Vowels): logos "the word" logou from *logosyo "of the word". The dative plural of Attic-Ionic had -oisi, which appears in early Attic but later simplifies to -ois: anthropois "to or for the men".

Classical Attic

Classical Attic may refer either to the varieties of Attic Greek spoken and written in Greek majuscule[12] in the 5th and 4th centuries BC (Classical-era Attic) or to the Hellenistic and Roman [13] era standardized Attic Greek, mainly on the language of Attic orators and written in Greek uncial.

Attic replaces the Ionic -σσ with -ττ :

- Attic γλῶττα → Ionic γλῶσσα "tongue"

- Attic πράττειν → Ionic πράσσειν "to do, to act, to make"

- Attic θάλαττα → Ionic θάλασσα "sea"

Varieties

- The vernacular and poetic dialect of Aristophanes.

- The dialect of Thucydides (mixed Old Attic with neologisms).

- The dialect and the orthography of Old Attic inscriptions in Attic alphabet before 403 BC. The Thucydidean orthography is similar.

- The conventionalized and poetic dialect of the Attic tragic poets, mixed with Epic and Ionic Greek and used in the episodes. (In the choral odes, conventional Doric is used).

- Formal Attic of Attic orators, Plato,[14] Xenophon and Aristotle, imitated by the Atticists or Neo-Attic writers, and considered to be good or Standard Attic.

See also

Notes

- Roger D. Woodard (2008), "Greek dialects", in: The Ancient Languages of Europe, ed. R. D. Woodard, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 51.

- From Goodwin and Gulick's classic text "Greek Grammar" (1930)

- Kirchhoff, Adolf (1867), Studien zur Geschichte des Griechischen Alphabets.

- Jeffery, Lilian H. (1961). The local scripts of archaic Greece. Oxford: Clarendon. 67, 81

- Threatte 1980, pp. 26ff.

- Smyth, par. 30 and note, 31: long a in Attic and dialects

- Liddell and Scott, κόρη.

- Paul Kiparsky, "Sonorant Clusters in Greek" (Language, Vol. 43, No. 3, Part 1, pp. 619–635: Sep. 1967) on JSTOR.

- V = vowel, R = sonorant, s is itself. VV = long vowel, RR = doubled or long sonorant.

- Liddell and Scott, κόρη.

- Γ.Ν. Χατζιδάκις, Σύντομος ιστορία της ελληνικής γλώσσης, page 40: "Some special characteristics of the Attic dialect are [...] the double -ρρ instead of -ρσ and the double -ττ instead of -σσ [...] . (Translated from Greek).

- Only the excavated inscriptions of the era. The Classical Attic works are transmitted in uncial manuscripts

- Including the Byzantine Atticists.

- Platonic style is poetic

References

- Buck, Carl Darling (1955). The Greek Dialects. The University of Chicago Press.

- Goodwin, William W. (1879). Greek Grammar. Macmillan Education. ISBN 0-89241-118-X.

- Smyth, Herbert Weir (1920). Greek Grammar. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-36250-0.

- Threatte, Leslie (1980). The grammar of Attic inscriptions. Vol. I: Phonology. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Further reading

- Allen, W. Sidney. 1987. Vox Graeca: The pronunciation of Classical Greek. 3rd ed. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Bakker, Egbert J., ed. 2010. A companion to the Ancient Greek language. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Christidis, Anastasios-Phoivos, ed. 2007. A history of Ancient Greek: From the beginnings to Late Antiquity. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Colvin, Stephen C. 2007. A historical Greek reader: Mycenaean to the koiné. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Horrocks, Geoffrey. 2010. Greek: A history of the language and its speakers. 2nd ed. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Palmer, Leonard R. 1980. The Greek language. London: Faber & Faber.

- Teodorsson, Sven-Tage. 1974. The phonemic system of the Attic dialect 400–340 BC. Gothenburg, Sweden: Institute of Classical Studies, University of Göteborg.

- Threatte, Leslie. 1980–86. The grammar of Attic inscriptions. 2 vols. Berlin: de Gruyter.

- Γεώργιος Μπαμπινιώτης, Συνοπτική Ιστορία τής Ελληνικής γλώσσας, Athens 2002.

External links

| Library resources about Attic Greek |

- English-Attic Dictionary (Woodhouse)

- Perseus Digital Library

- Greek Word Study Tool (Perseus)

- A Greek Grammar for Colleges (Smyth) Archived 2015-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Syntax of Classical Greek (Gildersleeve) Archived 2015-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- Ancient Greek Tutorials – Provides Attic Greek audio recordings

- Classical (Attic) Greek Online