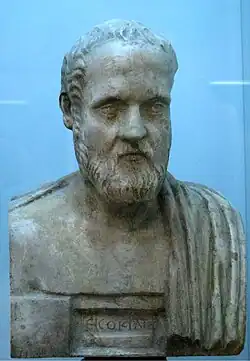

Isocrates

Isocrates (/aɪˈsɒkrətiːz/; Ancient Greek: Ἰσοκράτης [isokrátɛ̂ːs]; 436–338 BC) was an ancient Greek rhetorician, one of the ten Attic orators. Among the most influential Greek rhetoricians of his time, Isocrates made many contributions to rhetoric and education through his teaching and written works.

Greek rhetoric is commonly traced to Corax of Syracuse, who first formulated a set of rhetorical rules in the fifth century BC. His pupil Tisias was influential in the development of the rhetoric of the courtroom, and by some accounts was the teacher of Isocrates. Within two generations, rhetoric had become an important art, its growth driven by social and political changes such as democracy and courts of law. Isocrates starved himself to death, two years before his 100th birthday.[1][2]

Early life and influences

Isocrates was born into a prosperous family in Athens at the height of Athens' power shortly before the outbreak of the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC). Suda writes that Isocrates was the son of Theodorus who owned a workshop that manufactured aulos. His mother's name was Heduto. He had a sister and three brothers; two of the brothers were Tisippos (Ancient Greek: Τίσιππος) and Theomnestos (Ancient Greek: Θεόμνηστος).[3][4]

Isocrates received a first-rate education. "He is reported to have studied with several prominent teachers, including Tisias (one of the traditional founders of rhetoric), the sophists Prodicus and Gorgias, and the moderate oligarch Theramenes, and to have associated with Socrates, but these reports may reflect later views of his intellectual roots more than historical fact".[3]

He passed his youth in a gloomy period following the death of Pericles, a great Athenian leader and statesman, it was a period in which wealth – both public and private – was dissipated, and political decisions were ill-conceived and violent. Isocrates would have been 14 years old when the democracy voted to kill all the male citizens of the small Thracian city of Scione.[5] There are accounts, including that of Isocrates himself,[6] stating that the Peloponnesian War wiped out his father's estate, and Isocrates was forced to earn a living.[7]

Late in his life, he married a woman named Plathane (daughter of the sophist Hippias) and adopted Aphareus (writer), one of her sons by a previous marriage.[3]

Career

"Isocrates apparently avoided public life during the unstable years of the Peloponnesian War" (431–404).[3]

His professional career is said to have begun with logography: he was a hired courtroom speechwriter. Athenian citizens did not hire lawyers; legal procedure required self-representation. Instead, they would hire people like Isocrates to write speeches for them. Isocrates had a great talent for this since he lacked confidence in public speaking. His weak voice motivated him to publish pamphlets and although he played no direct part in state affairs, his written speech influenced the public and provided significant insight into major political issues of the day.[8]

Around 392 BC he set up his own school of rhetoric (at the time, Athens had no standard curriculum for higher education; sophists were typically itinerant), and proved to be not only an influential teacher but a shrewd businessman. His fees were unusually high, and he accepted no more than nine pupils at a time. Many of them went on to be prominent philosophers, legislators, historians, orators, writers, and military and political leaders.[3][9] As a consequence, he amassed a considerable fortune. According to Pliny the Elder (NH VII.30) he could sell a single oration for twenty talents. "At the core of his teaching was an aristocratic notion of arete ("virtue, excellence"), which could be attained by pursuing philosophia – not so much the dialectical study of abstract subjects like epistemology and metaphysics that Plato marked as "philosophy" as the study and practical application of ethics, politics and public speaking".[3]

Program of rhetoric

According to George Norlin, Isocrates defined rhetoric as outward feeling and inward thought of not merely expression, but reason, feeling, and imagination. Like most who studied rhetoric before and after him, Isocrates believed it was used to persuade ourselves and others, but also used in directing public affairs. Isocrates described rhetoric as "that endowment of our human nature which raises us above mere animality and enables us to live the civilized life."[10] Isocrates unambiguously defined his approach in the speech "Against the Sophists".[11] This polemic was written to explain and advertise the reasoning and educational principles behind his new school. He promoted broad-based education by speaking against two types of teachers: the Eristics, who disputed about theoretical and ethical matters, and the Sophists, who taught political debate techniques.[9] Also, while Isocrates is viewed by many as being a rhetor and practicing rhetoric, he refers to his study as philosophia—which he claims as his own. "Against the Sophists" is Isocrates' first published work where he gives an account of philosophy. His principal method is to contrast his ways of teaching with Sophistry. While Isocrates does not go against the Sophist method of teaching as a whole, he emphasizes his disagreement with bad Sophistry practices.[12]

Isocrates' program of rhetorical education stressed the ability to use language to address practical problems, and he referred to his teachings as more of a philosophy than a school of rhetoric. He emphasized that students needed three things to learn: a natural aptitude which was inborn, knowledge training granted by teachers and textbooks, and applied practices designed by educators.[9] He also stressed civic education, training students to serve the state. Students would practice composing and delivering speeches on various subjects. He considered natural ability and practice to be more important than rules or principles of rhetoric. Rather than delineating static rules, Isocrates stressed "fitness for the occasion," or kairos (the rhetor's ability to adapt to changing circumstances and situations). His school lasted for over fifty years, in many ways establishing the core of liberal arts education as we know it today, including oratory, composition, history, citizenship, culture, and morality.[9]

The first school of rhetoric

Prior to Isocrates, teaching consisted of first-generation Sophists, walking from town to town as itinerants, who taught any individuals interested in political occupations how to be effective in public speaking. Some popular itinerants of the late 5th century BC include Gorgias and Protagoras.[13] Around 392-390 BC, Isocrates founded his academy in Athens at the Lyceum, which was known as the first academy of rhetoric. The foundation of this academy brought students to Athens to study. Prior to this, teachers travelled amongst cities giving lectures to anyone interested.[13] The first students in Isocrates' school were Athenians. However, after he published the Panegyricus in 380 BC, his reputation spread to many other parts of Greece.[10] Following the founding of Isocrates' academy, Plato (a rival of Isocrates) founded his own academy as a rival school of philosophy.[13] Isocrates encouraged his students to wander and observe public behavior in the city (Athens) to learn through imitation. His students aimed to learn how to serve the city.[13] Some of his students included Isaeus, Lycurgus, Hypereides, Ephorus, Theopompus, Speusippus, and Timotheus. Many of these students remained under the instruction of Isocrates for three to four years. Timotheus had such a great appreciation for Isocrates that he erected a statue at Eleusis and dedicated it to him.[10]

Other influences

Because of Plato's attacks on the sophists, Isocrates' school – having its roots, if not the entirety of its mission, in rhetoric, the domain of the sophists – came to be viewed as unethical and deceitful. Yet many of Plato's criticisms are hard to substantiate in the actual work of Isocrates; at the end of Phaedrus, Plato even shows Socrates praising Isocrates (though some scholars have taken this to be sarcasm). Isocrates saw the ideal orator as someone who must possess not only rhetorical gifts, but also a wide knowledge of philosophy, science, and the arts. He promoted the Greek ideals of freedom, self-control, and virtue; in this, he influenced several Roman rhetoricians, such as Cicero and Quintilian, and influenced the core concepts of liberal arts education.

Isocrates' innovations in the art of rhetoric paid closer attention to expression and rhythm than any other Greek writer, though because his sentences were so complex and artistic, he often sacrificed clarity.[8]

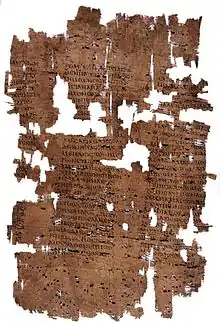

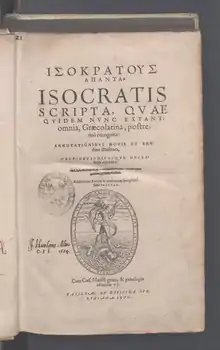

Of the 60 orations in his name available in Roman times, 21 remained in transmission by the end of the medieval period. The earliest manuscripts dated from the ninth or tenth century, until fourth century copies of Isocrates' first three orations were found in a single codex during a 1990's excavation at Kellis, a site in the Dakhla Oasis of Egypt.[14][15] We have nine letters in his name, but the authenticity of four of those has been questioned. He is said to have compiled a treatise, the Art of Rhetoric, but there is no known copy. Other surviving works include his autobiographical Antidosis, and educational texts such as Against the Sophists.

Isocrates wrote a collection of ten known orations, three of which were directed to the rulers of Salamis on Cyprus. In To Nicocles, Isocrates suggests first how the new king might rule best.[16] For the extent of the rest of the oration, Isocrates advises Nicocles of ways to improve his nature, such as the use of education and studying the best poets and sages. Isocrates concludes with the notion that, in finding the happy mean, it is better to fall short than to go to excess. His second oration concerning Nicocles was related to the rulers of Salamis on Cyprus; this was written for the king and his subjects. Isocrates again stresses that the surest sign of good understanding is education and the ability to speak well. The king uses this speech to communicate to the people what exactly he expects of them. Isocrates makes a point in stating that courage and cleverness are not always good, but moderation and justice are. The third oration about Cyprus is an encomium to Euagoras who is the father of Nicocles. Isocrates uncritically applauds Euagoras for forcibly taking the throne of Salamis and continuing rule until his assassination in 374 BC.[17]

Two years after his completion of the three orations, Isocrates wrote an oration for Archidamus, the prince of Sparta. Isocrates considered the settling of the Thebans colonists in Messene a violation of the Peace of Antalcidas. He was bothered most by the fact that this ordeal would not restore the true Messenians but rather the Helots, in turn making these slaves masters. Isocrates believed justice was most important, which secured the Spartan laws but he did not seem to recognize the rights of the Helots. Ten years later Isocrates wrote a letter to Archidamus, now the king of Sparta, urging him to reconcile the Greeks, stopping their wars with each other so that they could end the insolence of the Persians.[17]

At the end of the Social War in 355 BC, 80-year-old Isocrates wrote an oration addressed to the Athenian assembly entitled On the Peace; Aristotle called it On the Confederacy. Isocrates wrote this speech for the reading public, asking that both sides be given an unbiased hearing. Those in favour of peace have never caused misfortune, while those embracing war lurched into many disasters. Isocrates criticized the flatterers who had brought ruin to their public affairs.[17]

Lasting influence

Although Isocrates has been largely marginalized in the history of philosophy,[18] Isocrates' contributions to the study and practice of rhetoric have received more attention. Emeritus Thomas M. Conley argues that through Isocrates' influence on Cicero, whose writings on rhetoric were the most widely and continuously studied until the modern era, "it might be said that Isocrates, of all the Greeks, was the greatest."[19] With the neo-Aristotelian turn in rhetoric, Isocrates' work sometimes gets cast as a mere precursor to Aristotle's systematic account in On Rhetoric.[20] However, Ekaterina Haskins reads Isocrates as an enduring and worthwhile counter to Aristotelian rhetoric. Rather than the Aristotelian position on rhetoric as a neutral tool, Isocrates understands rhetoric as an identity-shaping performance that activates and sustains civic identity.[20] The Isocratean position on rhetoric can be thought of as ancient antecedent to the twentieth century theorist Kenneth Burke's conception that rhetoric is rooted in identification.[21] Isocrates' work has also been described as proto-Pragmatist, owing to his assertion that rhetoric makes use of probable knowledge with the aim resolving real problems in the world.[18][22]

Publications

Antidosis

Panathenaicus

In Panathenaicus, Isocrates argues with a student about the literacy of the Spartans. In section 250, the student claims that the most intelligent of the Spartans admired and owned copies of some of Isocrates' speeches. The implication is that some Spartans had books, were able to read them, and were eager to do so. The Spartans, however, needed an interpreter to clear up any misunderstandings of double meanings which might lie concealed beneath the surface of complicated words. This text indicates that some Spartans were not illiterate. This text is important to scholars' understanding of literacy in Sparta because it indicates that Spartans were able to read and that they often put written documents to use in their public affairs.

Major orations

- Ad Demonicum

- Ad Nicoclem

- Archidamus

- Busiris

- De Pace

- Evagoras

- Helena

- Nicocles

- Panegyricus

- Philippus

References

- Phillips, David D. (27 March 2003). "Orator Biographies". stoa.org. The Stoa. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- Potter, Ben (17 April 2015). "Isocrates: The Essayist". Classical Wisdom Weekly. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

In 338 BC, two years shy of Alexander's coronation and his own 100th birthday, Isocrates starved himself to death after yet another appeal to Philip fell on deaf ears.

- Isocrates (2004). Isocrates II. Translated by Terry L. Papillon. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70245-5 – via ProQuest Ebook Central.

- "SOL Search: iota,652". SUDA Encyclopedia. University of Kentucky. Retrieved 7 September 2020 – via cs.uky.edu.

- Cawkwell, G. Law. (27 August 2020). "Isocrates". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Isocrates. Antidosis. Vol. Section 161. Retrieved 7 September 2020 – via perseus.tufts.edu.

I had lost in the Peloponnesian War the patrimony which remained to me from what my father had spent....

- Dobson, J. F. "Chapter 6: Isocrates". The Greek Orators. Retrieved 7 September 2020 – via perseus.tufts.edu.

- Cawkwell, George Law (1998). Isocrates. ISBN 978-0-19-860165-4. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Matsen, Patricia, Philip Rollinson, and Marion Sousa. Readings from Classical Rhetoric. Southern Illinois: 1990.

- Norlin, George (1928). Isocrates. London W. Heinemann. pp. ix–xlvii.

- Readings in Classical Rhetoric By Thomas W. Benson, Michael H. Prosser. page 43. ISBN 0-9611800-3-X

- Livingstone, Niall (2007). "Writing Politics: Isocrates' Rhetoric of Philosophy". Rhetorica: A Journal of the History of Rhetoric. 25 (1): 15–34.

- Mitchell, Gordon. "Isocrates". Archived from the original on 18 September 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- "Ancient Kellis". Lib.monash.edu.au. 2 October 1998. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- Mirhady, David C. and Yun Lee Too, Isocrates I, University of Texas, 2000

- Avgousti, Andreas (2023). "The household in Isocrates' political thought". European Journal of Political Theory. 22 (4): 523–541. doi:10.1177/14748851211073728. ISSN 1474-8851. S2CID 246303666.

- Beck, Sanderson. Greece & Rome to 30 BC (Volume 4 ed.). Ethics of Civilization.

- Matson, W. I. (1957). "Isocrates the Pragmatist". The Review of Metaphysics. 10 (3): 423–427. ISSN 0034-6632. JSTOR 20123586.

- Conley, Thomas M. (1990). Rhetoric in the European tradition. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-8013-0256-0. OCLC 20013261.

- Haskins, Ekaterina V. (2010). Logos and power in Isocrates and Aristotle. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-873-0. OCLC 632088737.

- Haskins, Ekaterina (July 2006). "Choosing between Isocrates and Aristotle: Disciplinary Assumptions and Pedagogical Implications". Rhetoric Society Quarterly. 36 (2): 191–201. doi:10.1080/02773940600605552. ISSN 0277-3945. S2CID 145521219.

- Michele Kennerly; Damien Smith Pfister, eds. (2018). Ancient rhetorics and digital networks. Tuscaloosa, Alabama. ISBN 978-0-8173-9157-7. OCLC 1021296931.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Further reading

- Benoit, William L. (1984). "Isocrates on Rhetorical Education". Communication Education. 33 (2): 109–119. doi:10.1080/03634528409384727.

- Bizzell, Patricia; Herzberg, Bruce, eds. (2001). The rhetorical tradition: Readings from classical times to the present (2nd ed.). Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's. ISBN 978-0-312-14839-3.

- Bury, J.B. (1913). A History of Greece. Macmillan: London.

- Eucken, von Christoph (1983). Isokrates: Seine Positionen in der Auseinandersetzung mit den zeitgenössischen Philosophen (in German). Berlin: W. de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-008646-1.

- Golden, James L.; Berquist, Goodwin F.; Coleman, William E. (2007). The rhetoric of Western thought (9th ed.). Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall / Hunt. ISBN 978-0-7575-3838-4.

- Grube, G.M.A. (1965). The Greek and Roman Critics. London: Methuen.

- Haskins, Ekaterina V. (2004). Logos and power in Isocrates and Aristotle. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-526-5.

- Isocrates (1752), The Orations and Epistles, translated by Joshua Dinsdale (London, printed for T. Waller)

- Isocrates (2000). Isocrates I. David Mirhady, Yun Lee Too, trans. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-75237-5.

- Isocrates (2004). Isocrates II. Translated by Terry L. Papillon. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70245-5.

- Isocrates. Loeb Classical Library. Translated by George Norlin (vols. 1–2), Larue van Hook (vol. 3). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 1968. ISBN 978-0-674-99231-3.

- Livingstone, Niall (2001). A commentary on Isocrates' Busiris. Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12143-0.

- Muir, J. R. (2005). "Is our history of educational philosophy mostly wrong?: The case of Isocrates". Theory and Research in Education. 3 (2): 165–195. doi:10.1177/1477878505053300. S2CID 145489575.

- Muir, J. R. (2018). The Legacy of Isocrates and a Platonic Alternative. London: Routledge.

- Muir, J.R. (2022) Isocrates: Historiography, Methodology, and the Virtues of Educators. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Papillon, Terry (1998). "Isocrates and the Greek Poetic Tradition" (PDF). Scholia. 7: 41–61.

- Poulakos, Takis (1997). Speaking for the polis: Isocrates' rhetorical education. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-177-9.

- Poulakos, Takis; Depew, David J., eds. (2004). Isocrates and civic education. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70219-6.

- Waterfield, Robin (2002). "Notes". Plato's Phaedrus. Oxford University Press.

- Romilly, Jacqueline de (1985). Magic and rhetoric in ancient Greece. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-54152-8.

- Smith, Robert W.; Bryant, Donald C., eds. (1969). Ancient Greek and Roman Rhetoricians: A Biographical Dictionary. Columbia, Missouri: Artcraft Press.

- Too, Yun Lee (1995). The rhetoric of identity in Isocrates: text, power, pedagogy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47406-1.

- Too, Yun Lee (2008). A commentary on Isocrates' Antidosis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-923807-1.

- Usener, Sylvia (1994). Isokrates, Platon und ihr Publikum: Hörer und Leser von Literatur im 4. Jahrhundert v. Chr (in German). Tübingen: Narr. ISBN 978-3-8233-4278-6.