Ancient Hebrew writings

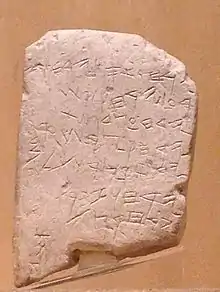

The earliest known precursor to Hebrew, an inscription in the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, is the Khirbet Qeiyafa Inscription (11th–10th century BCE),[1] if it can be considered Hebrew at that early a stage.

| History of literature by era |

|---|

| Ancient (corpora) |

| Early Medieval |

| Medieval by century |

| Early Modern by century |

| Modern by century |

| Contemporary by century |

|

|

By far the most varied, extensive, and historically significant body of literature written in Biblical Hebrew is the Hebrew scriptures (commonly referred to as the Tanakh), but certain other works have survived as well. Before the Aramaic-derived Hebrew alphabet was adopted circa the 5th century BCE, the Phoenician-derived Paleo-Hebrew alphabet was used for writing, and a derivative of the script still survives to this day in the form of the Samaritan script.

Origins, dialects and classification

The Hebrew language developed out of the Canaanite language, and some Semitist scholars consider both Hebrew and Phoenician to have been essentially dialects of Canaanite.[7]

The language variety in which the Masoretic biblical text is written is known as Biblical Hebrew or Classical Hebrew (c. 10th century BCE – 1st century CE). Varieties of Hebrew were spoken not only by the ancient Israelites but also in adjacent kingdoms east and south of the Jordan River, where distinct non-Israelite dialects existed, now extinct: Ammonite, Moabite and Edomite. After the inhabitants of the Northern Kingdom of Israel had been deported from their homeland following the Assyrian conquest in approximately 721 BCE, an equivalent linguistic shift occurred. In the Second Temple period since the Babylonian exile, beginning in the 5th century BCE, the two known remnants of the twelve Israelite tribes came to be referred to as Jews and Samaritans (see Samaritan Hebrew).

Genealogical classification of Hebrew:

Unlike Samaritan and Biblical Hebrew, the other varieties are poorly studied due to insufficient data. It may be argued that they are independent languages, as the distinction between language and dialect is ambiguous. They are known only from very small corpora, coming from seals, ostraca, transliterations of names in foreign texts.

Hebrew and Phoenician are classified as Canaanite languages, which, along with Aramaic constitute the Northwest Semitic (Levantine) language family. Extra-biblical Canaanite inscriptions are gathered along with Aramaic inscriptions in editions of the book "Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften", from which they may be referenced as KAI n (for a number n); for example, the Mesha Stele is "KAI 181".

The Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible is commonly known in Judaism as the "Tanakh", it being a vocalization of the acronym TNK (תַּנַ"ךְ): Torah ("Teachings"), Nevi'im ("Prophets") and Ketuvim ("Writings"). In Christianity it's known as the "Old Testament". The Bible is not a single, monolithic piece of literature because each of these three sections, in turn, contains books written at different times by different authors.[8] All books of the Bible are not strictly religious in nature; for example, The Song of Songs is a love poem and, along with The Book of Esther, does not explicitly mention God.[9]

"Torah" in this instance refers to the Pentateuch (to parallel Chumash, חומש), so called because it consists of five books: Genesis, Exodus, Numbers, Leviticus and Deuteronomy. It is the core scripture of Judaism and Samaritanism, honored in these religions as the most sacred of scripture. It is sometimes called the "Five Books of Moses" because according to the Jewish tradition, the Torah, as a divinely inspired text, was given to Moses by God himself on Mount Sinai during the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt, which is portrayed as the founding event in the formation of the Israelite religion. Other than discussing the Exodus itself and the journey to the Promised Land, the Pentateuch has such themes as the origin of the world, of humanity and of the ancient Israelites, the ancestors of modern-day Jews.

The Nevi'im section of the Hebrew Bible consists of two sub-divisions: the Former Prophets (Nevi'im Rishonim נביאים ראשונים, the narrative books of Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings) and the Latter Prophets (Nevi'im Aharonim נביאים אחרונים, the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah and Ezekiel and the Twelve Minor Prophets). The first sub-division speaks much about the history of the Israelites following the death of Moses, arrival to the Promised Land and the history of the kingdom up until the Siege of Jerusalem by the Neo-Babylon Empire in 586 BCE.

The Ketuvim sector of the Hebrew Bible is a collection of philosophical and artistic literature believed to have been written under the influence of Ruach ha-Kodesh (the Holy Spirit). It consists of 11 books: Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, Chronicles, five books known as the Chamesh Megilot and three poetic books, including the Book of Psalms, quotations of which comprise a large portion of canonical daily prayers in Judaism.

Dating and authorship

The oldest manuscripts discovered yet, including those of the Dead Sea Scrolls, date to about the 2nd century BCE. While Jewish tradition holds that the Pentateuch was written between the 16th century and the 12th century BCE, secular scholars are virtually unanimous in rejecting these early datings, and agree that there was a final redaction some time between 900–450 BCE.[10][11] The traditional view is that all five books were written in immediate succession, but some scholars believe that Deuteronomy was written later than the other four books.[12]

The traditional Jewish view regarding the authorship of the Pentateuch is that it was written by Moses under God's order, except for the last eight verses of Deuteronomy which describe the death of Moses and was written by Joshua, Moses's student who became a prophet. In secular scholarly circles by the end of the 19th century, a popular proposition regarding the authorship was the documentary hypothesis, which has remained quite influential to this day, despite criticism. The books of the prophets are entitled in accordance with the alleged authorship. Some books in the Ketuvim are attributed to important historical figures (e.g., the Proverbs to King Solomon, many of the Psalms to King David), but it is generally agreed that verification of such authorship claims is extremely difficult if not impossible, and many believe some or even all of the attributions in the canon and the apocrypha to be pseudepigraphal.

Scholars believe that the Song of the Sea (Exodus 15) was compiled and passed orally before it was quoted in the Book of Exodus and that it is among the most ancient poems in the history of literature, perhaps going back to the 2nd millennium BCE.[13][14] The Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32:1–43) and the Song of Deborah (Judges 5) were written in Archaic Biblical Hebrew, also called Old Hebrew or Paleo-Hebrew (10th–6th centuries BCE, corresponding to the Monarchic Period until the Babylonian Exile).

Samaritan version of the Torah

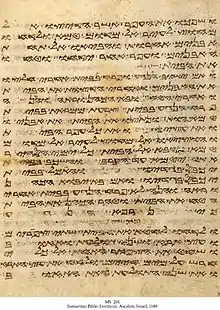

The only descendants of the Israelites who have preserved Hebrew texts are the Jews and the Samaritans and, of the latter, there are but a few hundred left.[15] Both the Samaritan religion and the indigenous Samaritan language, which today is used only liturgically, differ somewhat from their Jewish counterparts, though the difference between the language varieties is only dialectal. The canon of the Samaritans consists solely of a version of the Pentateuch. It is slightly different from the Jewish Masoretic version. Most are minor variations in the spelling of words or grammatical constructions, but others involve significant semantic changes, such as the uniquely Samaritan commandment to construct an altar on Mount Gerizim. Remarkably, it is to this day written in a script which developed from the paleo-Hebrew script (namely the Samaritan script), whereas the common "Hebrew script" is in fact a stylized version of the Aramaic script, not of the paleo-Hebrew script.[16]

Early rabbinic literature

Post-Biblical Hebrew writings include rabbinic works of Midrash, Mishnah, and Talmud. In addition, there are non-rabbinic Hebrew texts from the Second Temple and subsequent periods.

The subject of the Talmud is the Torah-derived Halakhah, Jewish religious law, which at the time of its writing was indistinguishable from secular law, as indeed the dichotomy had not yet arisen. The Talmud has two components to it: the Mishnah, which is the main text, redacted between 180 and 220 CE, and the Gemarah, the canonized commentary to the Mishnah. Very roughly, there are two traditions of Mishnah text: one found in manuscripts and printed editions of the Mishnah on its own, or as part of the Jerusalem Talmud (Talmud Yerushalmi), the other is found in manuscripts and editions of the Babylonian Talmud (Talmud Bavli). Unless otherwise specified, the word "Talmud" on its own is normally understood to mean the Babylonian Talmud.

The Jerusalem Talmud was compiled in the 4th century CE in Galilee, and the Babylonian Talmud was compiled about the year 500 CE, although it continued to be edited later. While the Pentateuch is sometimes called the "Written Torah", the Mishnah is contrasted as the "Oral Torah" because it was passed down orally between generations until its contents were finally committed to writing following the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, when Jewish civilization was faced with an existential threat.[17]

Descent from the Talmudic tradition is the defining feature of Rabbinic Judaism. In Rabbinic Judaism it is believed that the oral traditions codified in the Oral Torah were co-given with the Written Torah to Moses on Mount Sinai. This belief has, in contrast, been rejected by the Sadducees and Hellenistic Jews during the Second Temple period, the Karaites and Sabbateans during the early and later medieval period,[18] and in the modern non-Orthodox denominations: Reform Judaism sees all scripture as derived from human experience of the divine, Conservative Judaism holds that at the very least some of the oral law is man-made, and Reconstructionist Judaism denies the very idea of revelation.[19] The vast majority of Jews today come from a Rabbinic Jewish background. Karaite Judaism is considered the main contrast to Rabbinic Judaism in our days, but even though Karaites constituted close to half of the global Jewish population around the early 2nd millennium CE,[20] today there but a few tens of thousands left.[21][22]

The language and style of the Talmud

Of the two main components of the Babylonian Talmud, the Mishnah is written in Mishnaic Hebrew. Within the Gemara, the quotations from the Mishnah and the Baraitas and verses of Tanakh quoted and embedded in the Gemara are in Hebrew. The rest of the Gemara, including the discussions of the Amoraim and the overall framework, is in a characteristic dialect of Jewish Babylonian Aramaic.[23] There are occasional quotations from older works in other dialects of Aramaic, such as Megillat Taanit. Overall, Hebrew constitutes somewhat less than half of the text of the Talmud.

This difference in language is due to the long time period elapsing between the two compilations. During the period of the Tannaim (rabbis cited in the Mishnah), the spoken vernacular of Jews in Judaea was a late form of Hebrew known as Rabbinic or Mishnaic Hebrew, whereas during the period of the Amoraim (rabbis cited in the Gemara), which began around 200 CE, the spoken vernacular was Aramaic. Hebrew continued to be used for the writing of religious texts, poetry, and so forth.[24]

There are significant differences between the two Talmud compilations. The language of the Jerusalem Talmud is a Western Aramaic dialect, which differs from the form of Aramaic in the Babylonian Talmud. The Jerusalem Talmud is often fragmentary and difficult to read, even for experienced Talmudists. The redaction of the Babylonian Talmud, on the other hand, is more careful and precise. The law as laid down in the two compilations is basically similar, except in emphasis and in minor details. The Jerusalem Talmud has not received much attention from commentators, and such traditional commentaries as exist are mostly concerned with comparing its teachings to those of the Babylonian Talmud.

Miscellaneous extracanonical literature

Religious texts whose authenticity is not officially recognized are termed apocryphal. Many texts have been lost. No Sadducee texts are extant.

The Septuagint included 14 books accepted by Christians but excluded from the 24-book Hebrew Bible canon (i.e., Tanakh), not all of them written originally in Hebrew. The Greeks use the word Anagignoskomena (Ἀναγιγνωσκόμενα "readable, worthy to be read") to describe these books. The Eastern Orthodox Churches have traditionally included all of them in their Old Testaments. Most of them, the ones named Deuterocanonical, are considered canonical also by the Roman Catholic Church.

A significant number of apocryphal works was written in the Second Temple Period (530 BCE – 70 CE); see also Second Temple Judaism. Some examples:

- The Book of Jubilees, an alternative narration of Genesis and Exodus

- The Book of Enoch

- The Book of Tobit

- The Wisdom of Sirach

- Psalms 152–155

The discovery of the Qumran Caves Scrolls (3rd century BCE – 1st century CE),[25][26] unveiled previously unknown documents that shed light on the rules and beliefs of a particular group or groups within greater Judaism.[27] The Qumran Caves Scrolls encompass most of the Dead Sea Scrolls. They are associated with the Essenes. Notable examples:

- The Community Rule

- The War Scroll

- The Habakkuk Commentary

- The Rule of the Blessing

Sefer Yetzirah is arguably the earliest extant book on Jewish esotericism, although some early commentators treated it as a treatise on mathematical and linguistic theory as opposed to Kabbalah. In traditional lore, the book is ascribed to the Bronze Age patriarch Abraham.[28] Some critical scholars argue for the 2nd century BCE as an early date of its writing,[28] or the 2nd century CE,[29] or even later origins.[30]

Hekhalot literature is a genre of Jewish esoteric and revelatory texts produced some time between Late Antiquity – some believe from Talmudic times or earlier – to the Early Middle Ages.

Many non-canonical books are referenced in the Bible. Most of them have been lost.

References

- "Most ancient Hebrew biblical inscription deciphered". newmedia-eng.haifa.ac.il. 2010. Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2016-09-22. University of Haifa press release.

- The early history of God: Yahweh and the other deities in ancient Israel By Mark S. Smith, p. 20

- The Calendar Tablet from Gezer, Adam L Bean, Emmanual School of Religion Archived March 2, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Is it "Tenable"?, Hershel Shanks, Biblical Archaeology Review Archived December 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- Spelling in the Hebrew Bible: Dahood memorial lecture, By Francis I. Andersen, A. Dean Forbes, p. 56

- Pardee, Dennis (2013). Robert D. Holmstedt; Aaron Schade (eds.). "A Brief Case for the Language of the 'Gezer Calendar' as Phoenician". Linguistic Studies in Phoenician: 43.

- Rendsburg, Gary (1997). "Ancient Hebrew Phonology". Phonologies of Asia and Africa: Including the Caucasus. Eisenbrauns. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-57506-019-4.

- Riches, John (2000). The Bible: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-19-285343-1.

the biblical texts themselves are the result of a creative dialogue between ancient traditions and different communities through the ages

- "The Book of Esther Doesn't Mention God, Why is It in the Bible?". Discovery.

- "Introduction to the Pentateuch. Introduction to Genesis.". ESV Study Bible (1st ed.). Crossway. 2008. pp. xlii, 29–30. ISBN 978-1-4335-0241-5.

- RA Torrey, ed. (1994). "I-XI". The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth (11th ed.). Baker Academic. ISBN 978-0-8010-1264-8.

- Miller, Patrick D., Deuteronomy (John Knox Press, 1990) pp. 2–3

- Seymour Gitin, J. Edward Wright, J. P. Dessel. Confronting the Past: Archaeological and Historical Essays on Ancient Israel in Honor of William G. Dever, pp. 296–97.

- Brian D. Russell, The Song of the Sea: The Date of Composition and Influence of Exodus 15:1–21 (Studies in Biblical Literature 101; New York: Peter Lang, 2007). pp. xii + 215. ISBN 978-0-8204-8809-7.

- The Samaritan Update Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- A History of the Hebrew Language. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. 1993. ISBN 0-521-55634-1.

- Howard Schwartz, Tree of souls: the mythology of Judaism, Oxford University Press, 2004. p. lv

- "Karaite Jewish University". Kjuonline.com. Archived from the original on 2010-08-25. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- Elliot N. Dorff, The Question of Authority: Orthodox, Reform, and Conservative Theories of Revelation.

- A. J. Jacobs, The Year of Living Biblically, p. 69.

- Isabel Kershner, "New Generation of Jewish Sect Takes Up Struggle to Protect Place in Modern Israel", The New York Times 4 September 2013.

- Joshua Freeman. "Laying down the (Oral) law". The Jerusalem Post.

- "Judaic Treasures of the Library of Congress: The Talmud". American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise.

- Sáenz-Badillos, Ángel and John Elwolde. 1996. A history of the Hebrew language. pp. 170–171: "There is general agreement that two main periods of RH (Rabbinical Hebrew) can be distinguished. The first, which lasted until the close of the Tannaitic era (around 200 CE), is characterized by RH as a spoken language gradually developing into a literary medium in which the Mishnah, Tosefta, baraitot, and Tannaitic midrashim would be composed. The second stage begins with the Amoraim, and sees RH being replaced by Aramaic as the spoken vernacular, surviving only as a literary language. Then it continued to be used in later rabbinic writings until the 10th century in, for example, the Hebrew portions of the two Talmuds and in midrashic and haggadic literature."

- Grossman, Maxine. Rediscovering the Dead Sea Scrolls. pp. 48–51. 2010.

- VanderKam, James C.; Flint, Peter (2002). The Meaning of the Dead Sea Scrolls. New York: HarperSanFrancisco. p. 32.

- Abegg, Jr., Martin, Peter Flint, and Eugene Ulrich, The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English, San Francisco: Harper, 2002.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Yezirah, Sefer". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "Yezirah, Sefer". The Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. Retrieved 16 April 2013. - Benton, Christopher P. An Introduction to the Sefer Yetzirah (PDF).

- Kaplan, A. (1997) Sefer Yetzirah; The Book of Creation In Theory and Practice, San Francisco, Weiser Books. p. 219